by John Boston

The July Amazing is fronted by John Pederson, Jr.’s second cover, an agreeable Martian-ish scene, reminiscent of nothing so much as . . . Johnny Bruck on a good day. So maybe the new commitment to domestic artists isn’t quite the boon I thought it was. We’ll see.

by John Pederson, Jr.

The non-fiction this month is a bit less gripping than usual. White’s editorial recounts his unsatisfactory encounter with a woman who wanted to write an article about SF fandom, but apparently never did (or it never got published). He then segues to a discussion of Dr. Frederic Wertham and his campaign against comic books which culminated in his book The Seduction of the Innocent. Then, finally, to the point: Wertham is now saying he too will write about SF fandom and White doesn’t think it will be any good. He’s probably right, but until we see what Wertham produces, discussing it is a little pointless.

The letter column remains contentious but is getting a little repetitive; at this point it’s hard for anyone to say anything new about New Wave vs. Old Farts, and no more inviting topic has emerged. The fanzine reviews are as usual, and the book reviews . . . are missing, damn it! To my taste they have been about the liveliest part of the magazine. I hope the lapse is momentary.

But speaking of SF fandom, I’ll take this lack of much to talk about as an occasion to mention something fairly striking about the magazine’s contents under Ted White’s editorship: there is an unusually large representation of Fans Turned Pro, authors who have—like White—been heavily involved in organized SF fandom. This issue features Bob Shaw, a leading light of Irish fandom and heavy contributor to the celebrated fanzines Slant and Hyphen, who later won two Hugo Awards as best fanwriter among other distinctions; he also had a story in the second (7/69) White-edited issue. Greg Benford (once a co-editor with White of the also-celebrated fanzine Void) has one of his co-authored “Science in Science Fiction” articles (the fifth) in this issue, and three stories to boot in White’s eight issues, as well as regular appearances in the book review column. Robert Silverberg, who published a slightly earlier well-known fanzine Spaceship, supplied an impressive serial novel and has a story in this issue. Terry Carr, another renowned fan editor, had a story in the last issue. Alexei Panshin is not to my knowledge a fan publisher but has won the Best Fan Writer Hugo for his prolific contributions to others’ fanzines. Harlan Ellison (short story in 9/69 issue) published the legendary Dimensions in the 1950s. Joe L. Hensley (same) is a member of First Fandom and published a fanzine in the 1940s.

And what does it all mean? The floor is open for sober analysis and wild speculation.

Continue reading [June 12, 1970] Something Good! and Nothing Terrible (July 1970 Amazing) →

![[June 16, 1970] <i>Solaris</i>, <i>Year of the Quiet Sun</i>…and a host of others (June 1970 Galactoscope #1)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700616covers-672x372.jpg)

![[June 14, 1970] Talkin' Loud, Swingin' Soft (June 1970 <i>Watermelon Man, The Landlord, and Cotton Comes to Harlem</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700614movies-672x372.jpg)

![[June 12, 1970] Something Good! and Nothing Terrible (July 1970 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/amz-0770-cover-672x372.png)

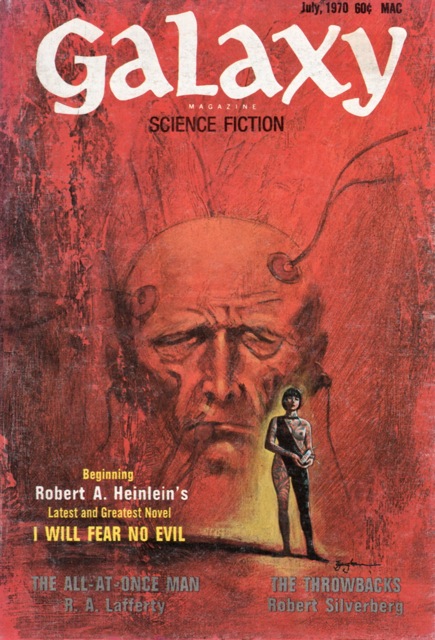

![[June 10, 1970] I will fear <i>I Will Fear No Evil</i> (July 1970 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700610galaxycover-435x372.jpg)

![[June 8, 1970] Beneath the Planet of the… Mutants? (Not Apes)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/beneath1-565x372.jpg)

by Jason Sacks

by Jason Sacks

![[June 2, 1970] Turning Up The Heat (<i>Doctor Who</i>: Inferno)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700603abitundertheweather-672x372.jpg)

![[May 31, 1970] A Compulsion to read (June 1970 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/700531analogcover-672x372.jpg)

![[May 28, 1970] A pair of Saras: <i>Flower of Doradil</i> and <i>A Promising Planet</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/ace_double-672x372.png)

![[May 26, 1970] A Regrettable Case of Runaway Apophenia (Erich von Däniken's <i>Memories of the Future</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Image-1-672x372.jpg)

![[May 22, 1970] Back From The Dead (Summer 1970 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/COVERSMALL-1-672x372.jpg)