by John Boston

Continuity and Change

Yeah, yeah, I know that’s the most boring headline since the last time Hubert Humphrey made a speech. But that’s what everybody (well, somebody) wants to know: how is the new Amazing different, or not, from the old one?

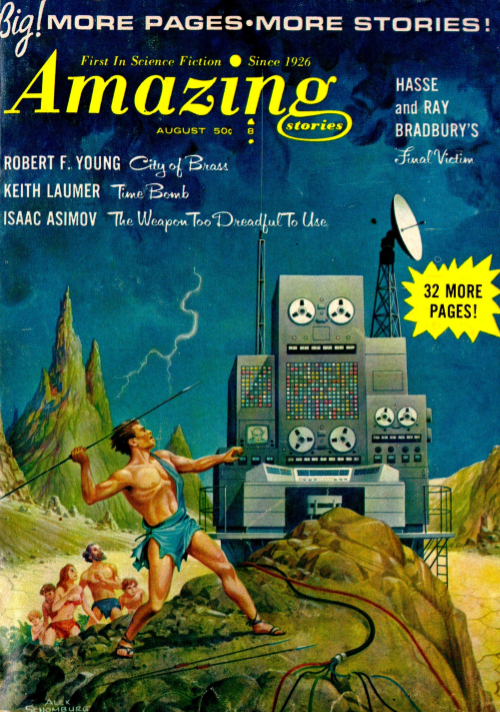

Some things we already knew. It’s still digest size, now bimonthly, with 32 more pages for a total of 162. On the cover there is a piece of retro-continuity; the new regime has dropped the old title logo for the older title logo, the one used from October 1960 to December 1963, with very minor variations—an improvement, to my taste. There’s a fairly generic cover by Alex Schomburg (I am certain the departed editor Lalli had a closet full of these) portraying, as you see, a guy in a loincloth brandishing a spear at a giant computer: Progress vs. Savagery, or Regimentation vs. Natural Freedom, as you prefer. It is said on the contents page to illustrate Keith Laumer’s Time Bomb. It does not. There are a number of interior illustrations. Coming Next Month has not returned.

by Alex Schomburg

And on the contents page . . . oh no. The blazing insignia of continuity are . . . Ensign De Ruyter and Robert F. Young. Forty-six pages of Robert F. Young. Well, let us keep an open mind; here, brace it with this two-by-four. Anyway, it’s a mistake to infer too much from this month’s fiction contents, since the new management will likely be burning off the inherited Ziff-Davis inventory for some months.

The non-fiction includes another of Robert Silverberg’s articles on scientific hoaxes, and Silverberg’s book review column—good signs if they are signs, but they too may just be what Lalli left behind. Ironically, the review column is devoted entirely to reprints, ranging from Wells to Sturgeon. There is also an editorial, in which Sol Cohen—listed on the contents page as Editor and Publisher—first demonstrates that he can be just as boring as his predecessor in editorializing Norman Lobsenz, and then offers a lame explanation of his plans regularly to publish reprints from old issues of the magazine.

As for the reprints themselves, Cohen has gone for big names, with early short stories from Isaac Asimov and Ray Bradbury: respectively, The Weapon Too Dreadful To Use from the May 1939 issue, and Final Victim (with Henry Hasse), from February 1946. Each is accompanied by an unsigned introduction, shorter and less bombastic than those by Sam Moskowitz for the “SF Classic” selections of the Ziff-Davis years. The original illustrations are reprinted along with the stories.

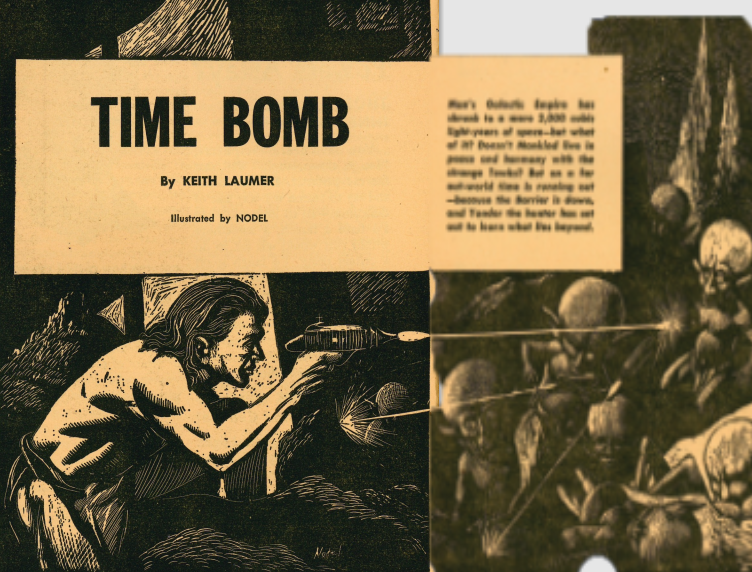

Time Bomb, by Keith Laumer

Keith Laumer’s novelet Time Bomb begins with Yondor, the son of the chief, going over the mountain to look around. And he sees—danger! Wounded on the way back, he makes his way home and reports to the chief that their way of life is at risk and they must act! But the chief doesn’t want to hear it—hey! Wake up back there! If you’re bored, do something useful, like listing all the stories you’ve read that begin with this particular cliche.

by Nodel

Anyway, these primitive characters are the descendants of a human outpost, now menaced by the evil alien Tewk, and Yondor gets away from their attack and into a machine with a transportation system requiring only that he sit in a chair and pull a lever and he’ll be somewhere else. This is a convenient substitute for a plot, as Yondor blunders his way from place to place before learning enough to get back, rescue his people, and smite the bad guys. As generic melodrama goes, it’s smooth and clever enough that it might be mildly entertaining, say, if one were stuck in an airport waiting for a late plane. Two stars.

The City of Brass, by Robert F. Young

by Gray Morrow

On the other hand, remarkably, Robert F. Young’s The City of Brass is actually fairly amusing, and not offensively stupid like most of his other rehashes of myths, legends, testaments, etc. Billings of Animannikins, Inc., has flown in his time sled back to the days of the Arabian Nights in order to kidnap Scheherazade, here rendered Shahrazad, bring her back to the present so his employers can work up a facsimile for public performance, and then return her to her fate. But Billings kicks some wires in the sled out of place and they wind up stranded in the age of the Jinn (which proves to be about 100,000 years in the future), not far from the Jinn’s brazen city of the title.

Shahrazad is undaunted. She doesn’t much like Jinn, and is in possession of a Seal of Solomon (here rendered Suleyman) with which she proposes to force all the Jinn into bottles and seal them up. Billings considers this a reckless plan, and goes out to reconnoiter, setting in train a ridiculous plot involving ridiculous revelations about the Jinn, their origin, and what has happened to humanity in the intervening millennia. This actually might have made it into John W. Campbell’s fantasy magazine Unknown if he had run short of material one month. Young’s familiar sentimentality about beautiful women and the men who are captivated by them threatens to take over, but the story ends quickly enough not to ruin the comic mood.

Three stars. I’ll put that two-by-four back in the shed.

The Weapon Too Dreadful to Use, by Isaac Asimov

by Julian Krupa

The reprints from Amazing’s past nicely illustrate the problems with reprinting from Amazing’s past. Asimov’s The Weapon Too Dreadful To Use is his second published story and shows it, with stilted writing, cliched characters and dialogue, and a muddled point. Humans have occupied Venus and are oppressing the natives, though supposedly racial discrimination and hostility have been eliminated on Earth. (Not too plausible.) The protagonist and his Venusian friend Antil trek to the ruins of a Venusian city and visit the science museum, which is largely intact, but no one has looked at it in living memory. (Even less plausible.) In a formerly sealed room, Antil finds the eponymous weapon, which can destroy people’s mental functions at interplanetary distances. (Plausibility meter breaks.) Venus rebels, Earth sends troops, Venus destroys the minds of a lot of them, Earth backs down and grants independence. It’s clear there’s a smart guy here trying to figure out how to write stories, but he’s not there yet. Two stars.

Final Victim, by Ray Bradbury and Henry Hasse

by Hadden

Bradbury and Hasse’s Final Victim is much worse. It is essentially a Bat Durston—a transplanted Western—about a bad deputy, excuse me, Patrolman, Skeel, who always kills the fugitives he is supposed to apprehend. His superior Anders knows his excuses are no good but can’t do anything, until Miss Miller, the sister of Skeel’s most recent kill, who has proven to be innocent of the accusation against him, decides to go after Patrolman Skeel. Anders, noting “the firm line of her chin, the trimness of her space uniform, the hard bold blueness of her eyes which he imagined could easily be soft on less drastic occasions than this,” decides to set her up to ambush Skeel herself out on the plains, I mean asteroids, and take revenge. But when things get really tough, Miss Miller faints. I stopped there. Forget stars. One mud pie.

The Good Seed, by Arthur Porges

Arthur Porges’s The Good Seed, as mentioned, is another in the series about Ensign De Ruyter. As usual it has some Earth guys at the mercy of treacherous primitive aliens, and they solve their problem with a scientific gimmick that you might find in the Fun with Science column of a kids’ magazine. One star.

John Keely’s Perpetual Motion Machine, by Robert Silverberg

Robert Silverberg comes to the rescue in his article about a guy who managed to make a pretty good career out of the perpetual motion con, but ironically might have had a better one developing the means of his fraud in the light of day. This is by far the best story in the issue, despite the fact that it is apparently true. Four stars.

Summing Up

Well, that was dismal, wasn’t it? Except for the Mitigation of Robert F. Young (can someone make a ballad out of that?) and Silverberg’s matter-of-fact competence at storytelling and -finding, nothing to see here, move on, move on.

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[July 14, 1965] The New Dispensation (August 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/amz0865-cover-500x372.png)

![[July 2, 1965] Gallimaufry (August 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/IF-cover-1965-08-649x372.jpg)

![[May 14, 1965] Keep A Civil Tongue In Your Head (July 1965 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v03n02_1965-07_0000-2-672x318.jpg)

![[May 8, 1965] Skip to the end (June 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/650508cover-535x372.jpg)

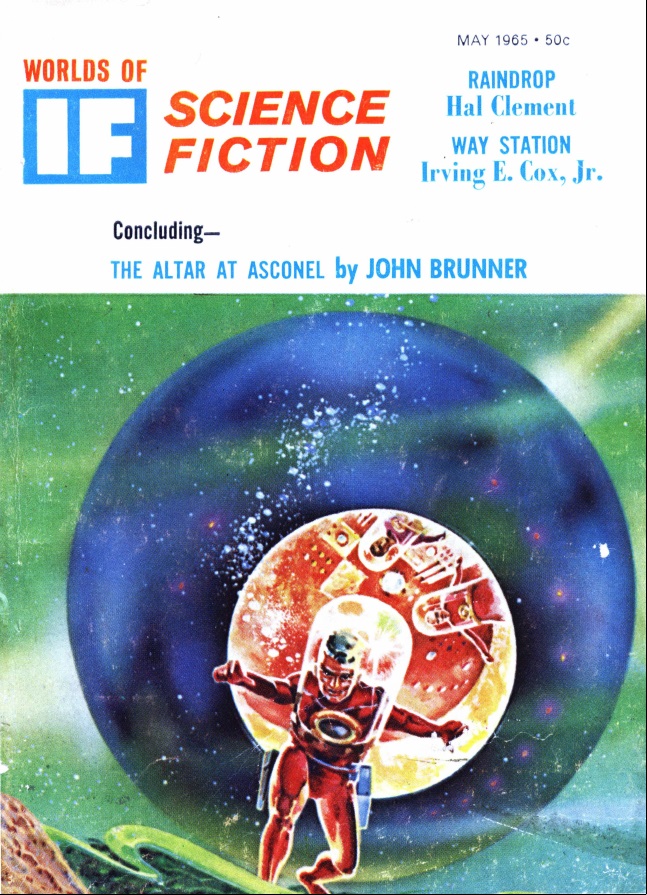

![[April 2, 1965] SPEAKING A COMMON LANGUAGE (May 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/IF-April-cover-647x372.jpg)

![[March 16, 1965] Browsing the Stacks (May 1965 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v03n01_1965-05_0000-2-672x316.jpg)

![[March 8, 1965] An Alien Perspective (April 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/650308cover-435x372.jpg)

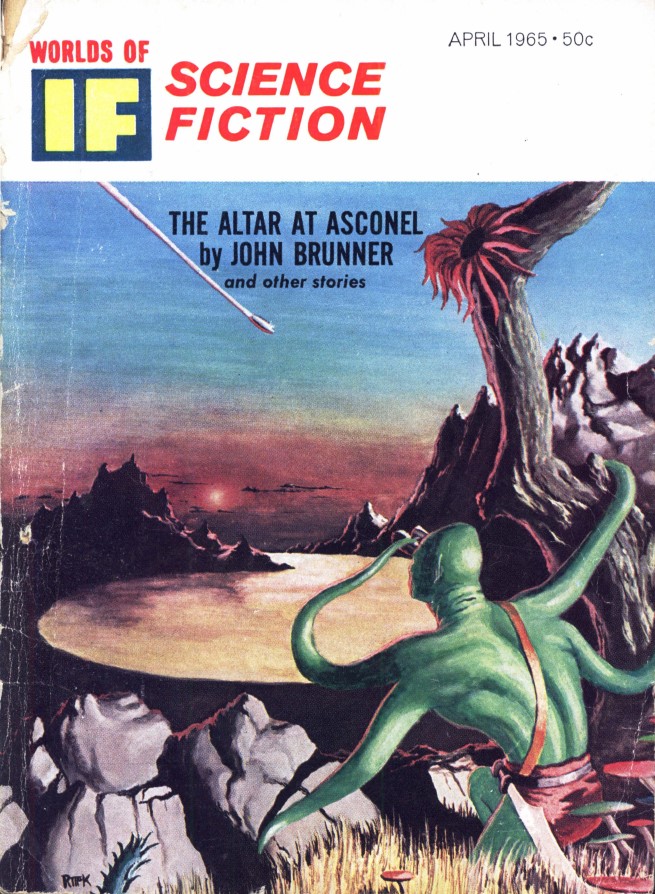

![[March 4, 1965] OLD WINE IN NEW BOTTLES (April 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/IF-march-cover-655x372.jpg)

![[January 26, 1965] Down the Rabbit Hole…Again (February 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/650126cover-672x372.jpg)

![[December 5, 1964] Steady as she goes (January 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/651205cover-672x372.jpg)