by John Boston

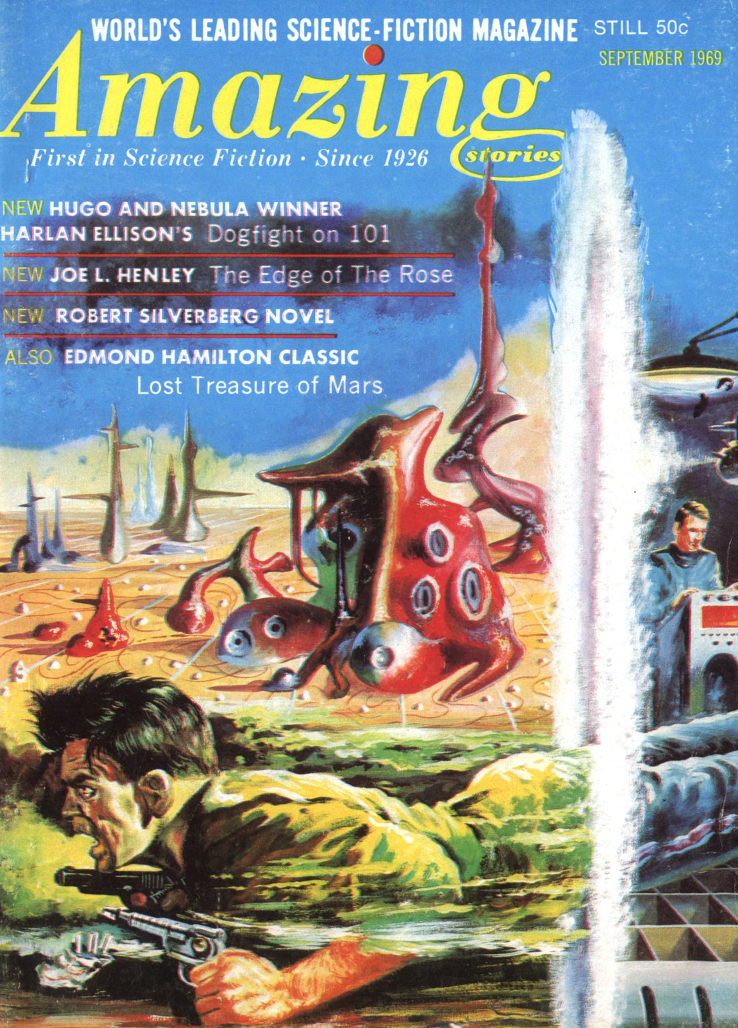

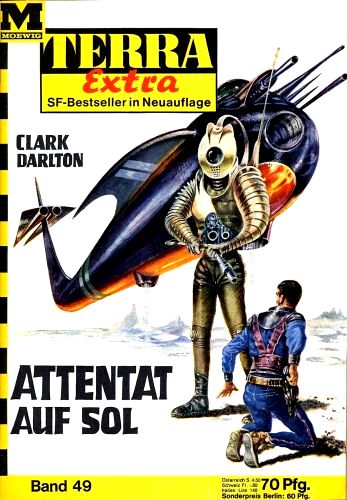

The September Amazing is fronted by one of Johnny Bruck’s more cliched covers, this one from Perry Rhodan #59 from 1962. It’s notable mainly for the fact that the guy with two guns and a fierce expression seems to be diving through a matter transmitter, and we see, impossibly, both the origin and destination of this dive. I guess it’s Omniscient Artist point of view.

by Johnny Bruck

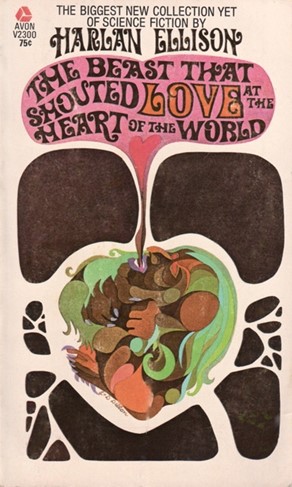

This issue, like the last, is dominated by the Silverberg serial Up the Line, which is supplemented by two reprinted novelettes, one new short story, and one short story billed as new: Harlan Ellison’s Dogfight on 101, which is reprinted not from an old Amazing, but from the August Adam, apparently one of the numerous Playboy imitators. In the letter column, editor White says to a complaining reader: “As you’ll note, the reprints have reached a new minimum in this issue—and we will be using the older, more ‘classic’ stories when possible.” That would be a relief!

As to the covers, White says: “At the present we are using cover paintings originally published in Europe, on European sf magazines. The reasons for this are complicated, but financial. In any case, the names of the artists are not known to us, or we would credit them. While control over the visual package of the magazine is beyond your Managing Editor, I have been able to commission stories around some of the paintings we have—and you’ll be seeing the first in our next issue, Greg Benford’s ‘Sons of Man.’ In cases where this has not been possible, we’ve tried to use covers which are in some sense symbolic of the stories in the issue—as with this issue’s, which seems to me at least loosely evocative of time-travel and Robert Silverberg’s Up the Line.” It’s not a connection I would have ever made on my own.

I complained about the last issue’s assorted typefaces of varying readability, and I wasn’t alone. White says to a correspondent “this was a result of a change in typesetters, and has been rectified with this issue, as you’ve already noticed. I share your feelings on the subject, since I proofed the galleys and suffered several headaches therefrom!” This issue’s typefaces are not entirely uniform, but there’s less variation and they are all readable, though all pretty small, making room for a lot more wordage than before.

There’s a long editorial by White, consisting of a potted history of the SF magazines segueing into commentary about Old Wave vs. New Wave, both fair-minded and forceful (and very quotable if only space permitted), ending up at the same obligatory place as his prior comments: he wants good stories from whatever camp. He mentions that one of the anti-New Wave partisans appears in the letter column—and how:

“New Thing writing has nothing whatsoever to do with style, but it has everything to do with content. This is the exact opposite of what most commentators say, but most commentators are wrong.

“The basis of the New Thing is what Colin Wilson refers to as the ‘insignificance premise,’ the idea that the universe is unknowable and life is meaningless—a popular notion with the ‘mainstream’ for a long time, as you are aware.

“It is the ‘insignificance premise’ that underlies the elements that are most praised by critics favoring the New Thing—the emphasis on the primacy of evil, on anti-heroes, on plotless stories, the rejection of science in favor of mysticism, and the worship of ugliness and disaster. . . .

“The ‘insignificance premise’ is the common denominator that underlies much-praised writers like Ballard, Disch, Ellison, Spinrad and Vonnegut. Style has nothing to do with it, in fact, New Thing writers can get away with the most atrocious style provided only their content reflects the devaluation of values.”

This is signed “Yours for the Second Foundation, John J. Pierce, liaison officer.”

Ohhh-kay. Moving right along: the book review column is as substantial as usual, and more than usually whiplash-inducing. James Blish reviewing John Brunner, and dismissing the Novel of Apparatus, writes: “I could not finish Stand on Zanzibar, since I disliked everybody in it and I was constantly impeded by the suspicion that Brunner was writing not for himself but for a Prize. I did finish The Jagged Orbit, but only because it was mercifully shorter. I recommend against it, and all others of its ilk. Most of them were dead ends before their authors and their enthusiasts had even been born.”

Turn the page and Norman Spinrad is reviewing Stand on Zanzibar and concluding: “If Stand on Zanzibar proves anything, it proves that the whole can be greater than the sum of its parts. None of the sections (the unedited film) are particularly brilliant by themselves. The total book is. It’s all in the editing.” But he cautions: “Stand on Zanzibar is a brilliant and dangerous book. Brilliant because with it Brunner has invented a whole new way of writing book-length sf. Dangerous because what he has done looks so damned easy. I predict (while hoping that I am wrong) that a lot of other sf writers are going to try their hands at books like this.” Other reviews include Greg Benford on Piers Anthony (“Omnivore isn’t that bad”), Blish again, as William Atheling, on Fred Saberhagen (lukewarm), and editor White on Hank Stine’s sex change novel Season of the Witch (“if not lip-smackingly good pornography, a reasonably good sf book, and a rather better novel qua novel”).

Leon Stover’s “Science of Man” article, John D. Berry’s fanzine review column and Laurence Janifer’s film review of Charly (“a disaster”) finish out the issue.

Well, that’s a lot of stuff. How good is it?

Up the Line (Part 2 of 2), by Robert Silverberg

Robert Silverberg’s Up the Line concludes in this issue (begun last issue). Judson Daniel Elliott III (Jud for short), former graduate student in Byzantine history, is at loose ends, having just fled a tiresome legal clerkship for New Orleans—Under New Orleans, that is. Cities are now underground. He walks into a sniffer palace (public drug den) looking to meet the pulchritudinous young women swimming nude in a tank of cognac as a come-on out front, and hits it off with Sam (formally, Sambo Sambo), who explains that his daddy bought his very black skin in a helix parlor (DNA shop). Sam invites everyone home with him for an evening of sex and (more) drugs.

So we are in an aggressively decadent future full of sex and drugs (sorry, no rock and roll). It’s also a future in which time travel is an amusement as accessible as transatlantic tourism is to us today. Sam, when he’s not minding the sniffer palace, is a Time Courier, leading tourists around in the past. Hearing of Jud’s soft spot for Byzantium, he suggests that Jud sign on too. Jud bites, and soon has his “timer”—“a smooth flat tawny thing that looked like a truss”—that will take him up and down the time-line.

There is training, of course, much of which focuses on paradoxes and how to avoid them, and the new hires are warned that their actions could wreck all of time, including their own present, and that the Time Patrol is watching for any transgressions.

What’s wrong with this picture? Maybe the idea that a technology that could destroy the world that developed it (speaking of paradoxes) would be left to an operation that screens and trains its employees about as thoroughly as a car rental agency might, and lets them go out leading tourists through past centuries with little visible supervision, is beyond belief, as is the notion that the Time Patrol is going to be able to identify all misdeeds and reliably correct them.

And in fact, Jud’s Time Courier colleagues mostly have their own anachronistic, or anti-chronistic, side ventures. His pal Sam has an enviable collection of new-looking period artifacts. Then there’s Dajani, taken off the Crucifixion beat after being found “conducting a side business in fragments of the True Cross, peddling them all up and down the timelines.” His punishment, decreed by the Time Patrol? Six months’ demotion to an instructorship teaching Jud and the other new hires! And Metaxas, who becomes Jud’s mentor, has set up a secondary identity for himself in early twelfth-century Byzantium, as a swell with a luxurious villa and large estate who hobnobs with the Emperor.

by Dan Adkins

And for some of the Time Couriers, time up the line has become a playground for their . . . pathologies? Eccentricities? The Courier Capistrano is systematically seeking out his ancestry, obsessed with the idea that when he is ready to die, he will find a particularly vile ancestor, kill him, and thus erase himself, or else be erased by the Time Patrol who will go further up and make him un-happen. And Metaxas is systematically seducing his female ancestors, because his father was cold and brutal, and so were his forebears—“It is my form of rebellion against the father-image. I go on and on through the past, seducing the wives and sisters and daughters of these men whom I loathe. Thus I puncture their icy smugness.”

Gives one confidence in time-line security, right? But the implausibility of the set-up is beside the point, since this is not a sober extrapolation of how a time-traveling world would work. Rather, its point—one of them, anyway—is to provide a hook for Silverberg to write an entertaining, colorful, and richly detailed story about visits to what seems to be one of his favorite stretches of history, which he does quite successfully. (Especially recommended is the Black Death tour, September issue, pages 41-43).

But there are other things going on. One of them is the author’s determination to smash, or at least drastically stretch, the usual proprieties of SF publishing. If novels still came with alternative titles (think Moby-Dick; or, The Whale), this one might have been Up the Line; or, Up Yours! The story is full of irreverent sexual references, often with misogynistic overtones. For example, trainee Jud is given a hypno-sleep course in Byzantine Greek, after which he “could order a meal, buy a tunic, or seduce a virgin in Byzantine argot.” Elsewhere: “The sweet fragrance of her drifted toward me. I began to ache and throb.” On a tour given by the above-mentioned Capistrano, an oil-lamp seller admires one of the women tourists, “taking a quick inventory and fastening on blonde and breasty Clotilde, the more voluptuous of our two German schoolteachers,” and “feeling the merchandise”; Capistrano chases him away (“I thought she was a slave!” protests the vendor). “Clotilde was trembling—whether from outrage or excitement, it was hard to tell. Her companion, Lise, looked a little envious.”

There are also a number of actual sexual encounters, described with a sort of arm's-length near-explicitness rarely found in the demure precincts of the genre magazines: “Metaxas sent his ancestress Eudocia into my bedroom that night. Her lean, supple body was a trifle meager for me. But she was a tigress. She was all energy and all passion, It was dawn before she let me sleep.” And some are much more cursory: “I bathed, slept, had a garlicky slavegirl two or three times, and brooded.” And there are other sorts of in-your-face vulgarity as well (remember Sam, actual name Sambo Sambo).

But back to the main plot and our main man. Jud doesn’t share Metaxas’s obsession with anachronistic incest, but does become preoccupied with tracing his ancestry in the region (his mother was Greek). Metaxas then tells him that he knows one of Jud’s ancestors in 1105, and offers to fix him up. (“She’s ripe for seduction. Young, childless, beautiful, bored. . . . and she’s your own great-great-multi-great-grandmother besides!”) And when Jud first lays eyes on her—“Our eyes met and held, and a current of pure force passed between us, and I quivered as the full urge hit me. She smiled only on the left side of her mouth, quirking the lips in, revealing two glistening teeth. It was a smile of invitation, a smile of lust.” She’s named—what better?—Pulcheria.

Metaxas is all too ready to arrange an opportunity and give Jud a cover story. And in the event: “She was shy and wanton at once, a superb combination.” As for him? It transcends the lubricious, and we will draw the curtain. Except, after a rest: “Redundancy is the soul of understanding.”

But storm clouds are gathering, and there’s a plot to be resolved. Jud returns from his tryst to find that Sauerabend, one of his tourist charges, has disappeared. He has gimmicked his timer so he can control it independently. Jud’s efforts, along with his time-posse of Courier friends, to track down Saurabend and restore the time-line without further disturbance ultimately fall short, at least for Jud’s purposes. Without giving more away, Silverberg milks the paradoxical possibilities of time travel for all they’re worth.

It’s a very readable and enjoyable novel, chockful of incident and colorful detail as well as definitively head-spinning play with time paradoxes. It’s also coarse, bawdy, and sexist. While it’s tempting to say “two out of three ain’t bad,” the treatment of women, who appear almost exclusively as sex objects or as near non-entities or ditzes among the tourists, is hard to swallow, and we will no doubt hear a lot about it when the reviews of the book start to appear. On balance, though, four stars.

But wait, there’s more! I have mentioned Silverberg’s assault on the proprieties of SF magazines. But Up the Line was written for book publication, and behold, the book has appeared from Ballantine as I was writing this. For those with a prurient interest in prurient interests and their satisfaction, we can compare the proprieties of magazine and book publication very directly. Usually, novels are cut for serial publication, but my very crude word count reveals little difference in length between book and serial versions, so it doesn’t appear that there’s been major cutting. Conveniently, both versions are divided into 63 short chapters. I have done some spot checks of textual differences, and they are mostly the sort you would expect.

Chapter 2 recounts Jud’s meeting Sam and the young women swimming in cognac, described above, and the only differences in text are italicized:

“Wearing gillmasks, they displayed their pretty nudities to the bypassers, promising but never quite delivering orgiastic frenzies. I watched them paddling in slow circles, each gripping the other’s left breast, and now and then a smooth thigh slid between the thighs of Helen or Betsy as the case may have been, and they smiled beckoningly at me and finally I went in.” There follows some snappy repartee as Jud and Sam meet cute, exchanging religious identities. Jud: “I’m a Revised Episcopalian, really.” Sam: “I’m First Church of Christ Voudoun. Shall I sing a [n-word] hymn?”

In Chapter 29, Jud, tracing his genealogy, meets his grandmother, who is at a ripe young age, and:

“It was lust at first sight. Her beauty, her simplicity, her warmth, captivated me instantly. I felt a familiar tickling in the scrotum and a familiar tightening of the glutei. I longed for her to rip away her clothing and sink myself deep into her hot tangled black shrubbery.”

And then there’s the encounter from Chapter 36 quoted above, brief in the magazine text but less so in the book: “Metaxas sent his ancestress Eudocia into my bedroom that night. Her lean, supple body was a trifle meager for me; her hard little breasts barely filled my hands. But she was a tigress. She was all energy and all passion, and she clambered on top of me and rocked herself to ecstasy in twenty quick rotations, and that was only the beginning. It was dawn before she let me sleep.”

And in Chapter 41, there’s a rather longer description—too long to quote—of an encounter, with Empress Theodora, no less, that Jud ultimately finds “mechanical and empty.” Then in the book is the following passage, completely omitted from the magazine:

“When I was fourteen years old, an old man who taught me a great deal about the way of the world said to me, ‘Son, when you’ve jizzed one snatch you’ve jizzed them all.’

“I was barely out of my virginity then, but I dared to disagree with him. I still do, in a way, but less and less each year. Women do vary—in figure, in passion, in technique and approach. But I’ve had the Empress of Bysantium [sic], mind you, Theodora herself. I’m beginning to think, after Theodora, that that old man was right. When you’ve jizzed one snatch you’ve jizzed them all.”

As for Jud’s rendezvous with Pulcheria, there’s a lot that got cut out of the magazine, but I will remain reticent. You can compare for yourselves in Chapter 47.

So, writers, editors, and publishers in this year of sixty-nine, er, 1969, you now have some clear signposts, if not a bright line, distinguishing the permissiveness of the magazine industry from that of book publishing. May you use them prudently.

Dogfight on 101, by Harlan Ellison

Ellison’s Dogfight on 101 is a heavy-handed satire on the less than original premise that highway driving has for some become a field for macho posturing. George the protagonist, with his wife or girlfriend in the car, is challenged by a punk named Billy and they go sailing down the road in their armed and armored vehicles trying to kill each other. A sample:

“George kicked it into Overplunge and depressed the selector button extending the rotating buzzsaws, Dallas razors, they were called, in the repair shoppes. But the crimson Merc pulled away doing an easy 115.

“ ‘I’ll get you, you beaver-sucker!’ he howled.” (Speaking of pushing the limits of SF magazines’ propriety.)

by Rick Steranko

And, in case you haven’t figured it out on your own: “ ‘My masculinity’s threatened,’ he murmured, and hunched over the wheel.”

This goes on for seven pages. Who knew that slam-bang action could get so tedious so quickly? In the end Billy gets his through a very old-fashioned maneuver by George, but that’s not the end; the story closes with a clanging anvil of irony.

But it’s certainly slickly done for what it is. At the end, Ellison gives credit where it’s due: “The Author wishes to thank Mr. Ben Bova of the Avco Everett Research Laboratory (Everett, Mass.) for his assistance in preparing the extrapolative technical background of this story.”

Two stars.

The Edge of the Rose, by Joe L. Hensley

Joe L. Hensley has published a sporadic trickle of stories in the SF magazines since 1953, with some detours into men’s magazines and several collaborations with Ellison. His The Edge of the Rose is an extremely well done routine story, with stock elements from the ‘50s SF toolbox nicely fitted together in classroom demo fashion. Stop here if you don’t want me to spoil the ending!

The SFnal setting, and the big problem: in the future, physical ailments have been conquered, but mental ones have multiplied. “Life was too technical, too complex, on a planet gone wild with factories supplying jewel-like parts for the light drive, on a planet still divided politically, where any day might bring the end. And men, the good ones, the ones who thought and tried, retreated from it all far too often—back to the warmth of the womb, security, and total dependency.” Only the extraterrestrial Tanna plant can treat this affliction. Protagonist Tosti wanted to be a doctor and do good like his dad, who died with back-to-the-wombism, but since the physical ailments are conquered, there’s no need for doctors. Feeling kind of empty, he signs up to go to Tanna to hunt the plant.

So along with the big problem, we’ve got a sympathetic character with his own smaller but existential problem. Tanna harvesting requires men (sic) to scour the rugged terrain of the planet, cut the plants they find, and get to high ground quickly so they can signal their ship to come get them before the plants deteriorate. But on the way up with his bag of plants, Tosti encounters a group of the Tanna natives, ill from Earth diseases the humans brought with them. He stops and builds a fire to keep them warm, and finds he can’t leave them; falls asleep; and when he wakes, they’re gone and his bag of plants is empty.

So he returns to base, unsuccessful, and the ship is about to leave, when who appears but a procession of the natives, bringing with them more Tanna plants than the humans have ever seen—live, robust growing plants, in pots! Tosti realizes he belongs here with the natives. (“This race had no one, and the terrible need of someone if they were to survive.”) So everybody’s problem is solved: the Tannanians are going to get some help, our empty-feeling protagonist has done good and sees how he can be sort of like Daddy, and Earth may be able to grow its own Tanna plants and cure all the womb-returners! And the reader gets the warm fuzzy feeling of happy endings for all. This is all done in hyper-efficient and plain language, scarcely a word wasted. Three stars for substance, four for craft that makes it read much better than its substance warrants. Though if every story were like this I’d get tired of them very fast.

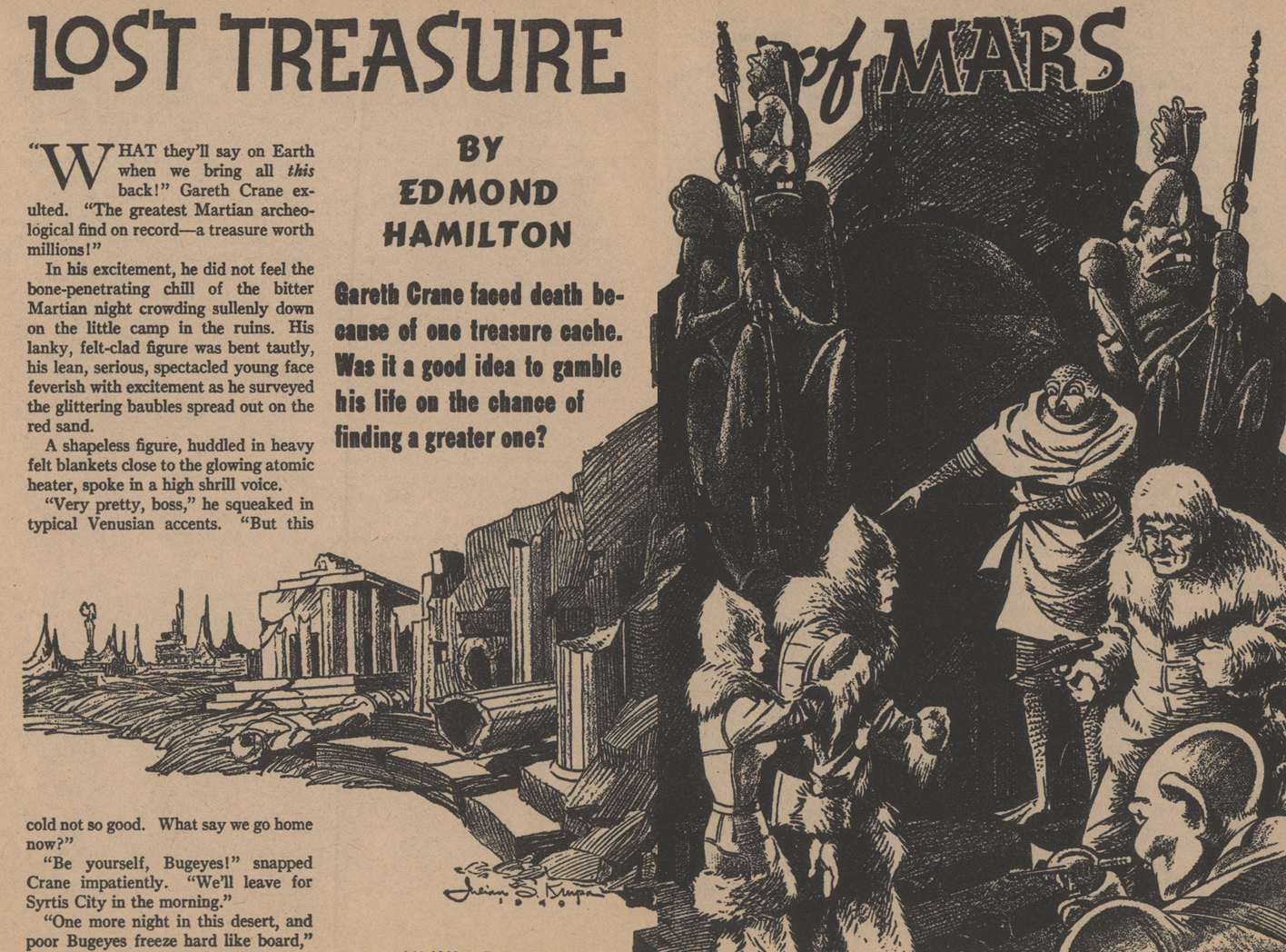

Lost Treasure of Mars, by Edmond Hamilton

Edmond Hamilton’s Lost Treasure of Mars, reprinted from Amazing, August 1940, is as hackneyed as its title. If editor White is going to use “the older, more ‘classic’ stories,” he hasn’t started yet. Archaeologist Gareth Crane is exulting over his find—"the legended jewel hoard of Kau-ta-lah, last of the great Martian kings of Rylik.” Just the thing to keep the Institute of Planetary Science, which fights the interplanetary microbial diseases that followed the development of space travel, in business! His servant Bugeyes, an “amphibian swampman” from Venus, is mainly preoccupied with how cold it is on Mars. (“ ‘Unlucky day when Bugeyes listen to Earthman’s blandishings and sign up for servant,’ he moaned.”) This near-Stepin Fetchit routine—indeed, the whole story—is a considerable comedown from much of Hamilton’s earlier work both in imagination and in maturity. Well, Ray Palmer was editor by 1940, and this seems to be what he wanted.

by Julian S. Krupa

And speaking of Palmer, and his editorial philosophy “Gimme bang-bang!”, on the next page after Bugeyes’s plaint, a rocket-car lands and two men and a woman get out (“ ‘A girl!’ Crane muttered. ‘What the devil—’ ”) The “girl” thinks Crane is seeking the treasure that in fact he’s already found by using her imprisoned father’s research. Her two companions, supposedly hired guides, are actually in business for themselves. Once they find the jewels Crane is hiding, they are deterred from killing everyone else only by Crane’s offer to lead them to an even greater treasure—the Greatest Treasure, in fact. So off they go to the ruined city of Ushtu! They are looking for the palace and its underground treasures, and of course there’s a trap in what seems to be the treasure chamber, and there’s no escape, except Bugeyes saves the day by going down the drain of a large vat of water, and the nature of the Greatest Treasure is revealed. Two stars, that high only because of Hamilton’s professional rendering of this cliché-pile.

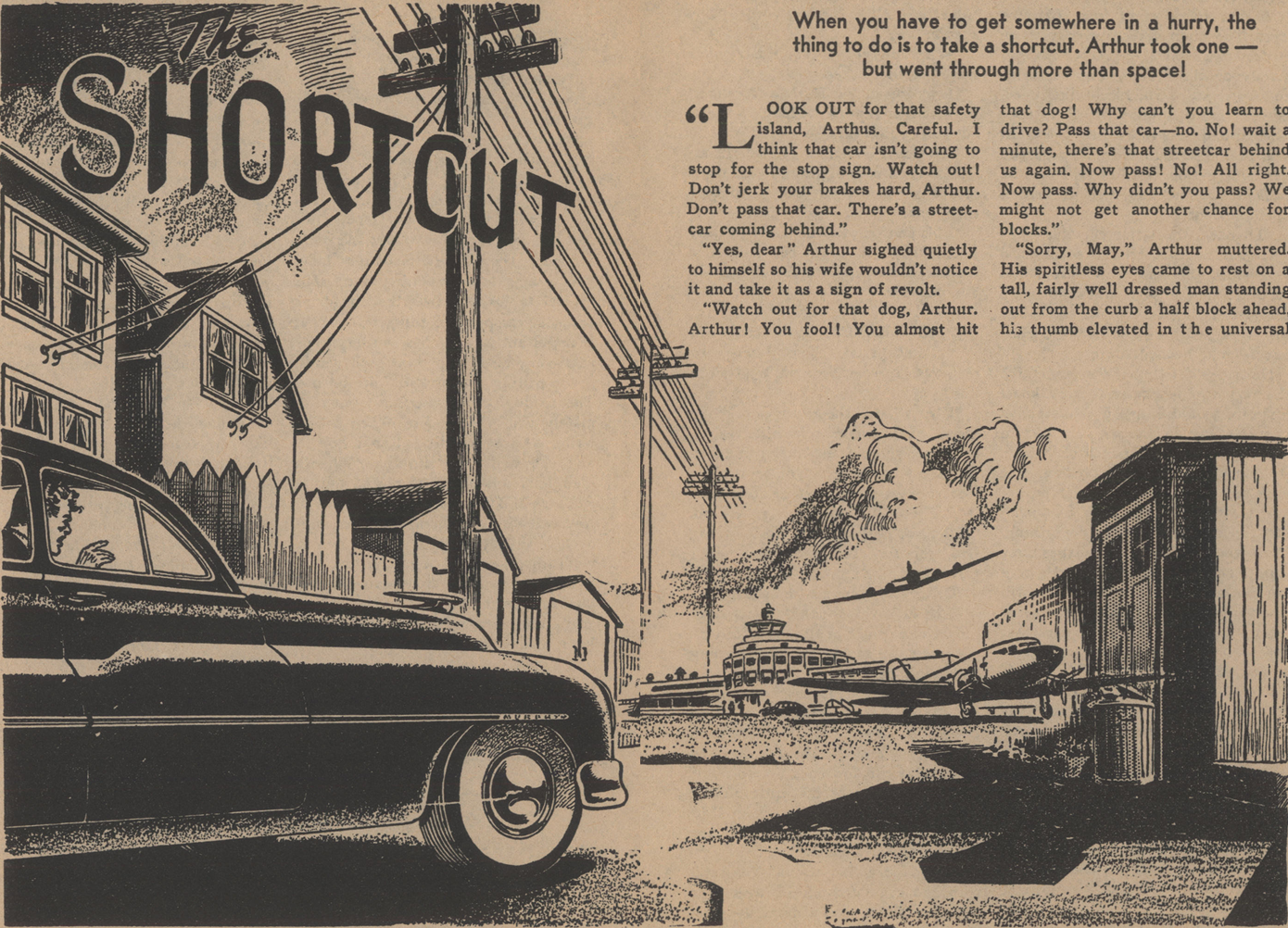

The Shortcut, by Rog Phillips

by Murphy Anderson

Rog Phillips’s The Shortcut (Amazing, July 1949) starts out with henpecked Arthur driving his wife May, an egregious backseat driver, to the Chicago airport. He picks up a hitchhiker because he knows May will quiet down with a stranger present. The hitchhiker suggests a shortcut which makes no sense, but it gets them to the airport in five minutes rather than 30. The hitchhiker gives a gibberish explanation for this. He suggests getting a meal, on him, and gives directions, and after several turns, they are in Hollywood. The hitchhiker buys a newspaper which reports that May’s plane has crashed, killing all aboard. Arthur is guiltily elated. Then the hitchhiker starts talking about shortcuts in time. He says “you can’t change things, but you can take advantage of them when you know the shortcuts.” Suddenly May is back in the back seat badgering him, and they’re back on the way to the airport. Arthur takes out a lot of insurance on her. Then he tries to take shortcuts on his own, gets lost, and winds up at a bigger airport than Chicago’s, where to his shock May disembarks and greets him. He has taken a final shortcut to where he definitely didn’t want to go.

This story, which revolves around glib double-talk reminiscent of Who’s On First?, reads like it was written for the even then defunct Unknown, though it might not have made the cut there. Still, clever and amusing. Three stars.

Wanted—A New Myth for Technology, by Leon E. Stover

In the letter column, one J. Edwards asks: “Dear Sirs: Why do you print ‘The Science of Man’?” Mr. Edwards doesn’t think much of science columns in SF magazines generally, but he also observes: “Stover’s columns read more like editorials than science columns; he seems mostly to be pushing his own opinions, and not much else.” Is there an echo in this subculture? Of Stover’s last article, I wrote: “Stover seems to have abandoned his project of educating us all about anthropology. Here we have a protracted editorial on the necessity for humanity to get its act together and get right with the biosphere. . . .” The editor responds: “You may (or may not) be pleased to hear that next issue we inaugurate a new science column, ‘The Science in Science Fiction,’ by Dr. Greg Benford.” While he does not say that Dr. Stover is history, that’s the implication.

Stover’s present article goes even further afield from anthropology than last issue’s, being a talk he gave at a symposium at the Illinois Institute of Technology, where he is “Chairman of a science fictionish Committee for Metatechnology.” He starts by summarizing at length an old story by H.G. Wells called The Lord of the Dynamos, and then begins his sermon: “Somehow, we’ve lost our affection for technology. Engineering enrollment is falling, student protests are rising. Who will make the machines and structures of tomorrow?” Excuse me if I tiptoe out of the church. Not rated. Welcome, Dr. Benford!

Summing Up

Not bad, still moving forward. Up the Line makes up for a number of sins, while adding its own. Amazing is a work in visible progress. I am trying not to say “promising” yet again.

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[August 10, 1969] Pushing the Envelope (September 1969 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/amz-0969-cover-672x372.png)

![[August 2, 1969] Specters of the past (September 1969 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/IF-1969-09-Cover-494x372.jpg)

Salvadoran President and General Fidel Sanchez Hernandez inspecting the troops.

Salvadoran President and General Fidel Sanchez Hernandez inspecting the troops. A robot carrying off a fainting human woman. It’s not as old-fashioned as you might think. Art by Chaffee

A robot carrying off a fainting human woman. It’s not as old-fashioned as you might think. Art by Chaffee![[July 31, 1969] Stranger than fiction (August 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/690731analogcover-672x372.jpg)

![[July 28, 1969] <i>New Worlds – on a Budget</i>, August 1969](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/cover-august-69-672x372.jpg)

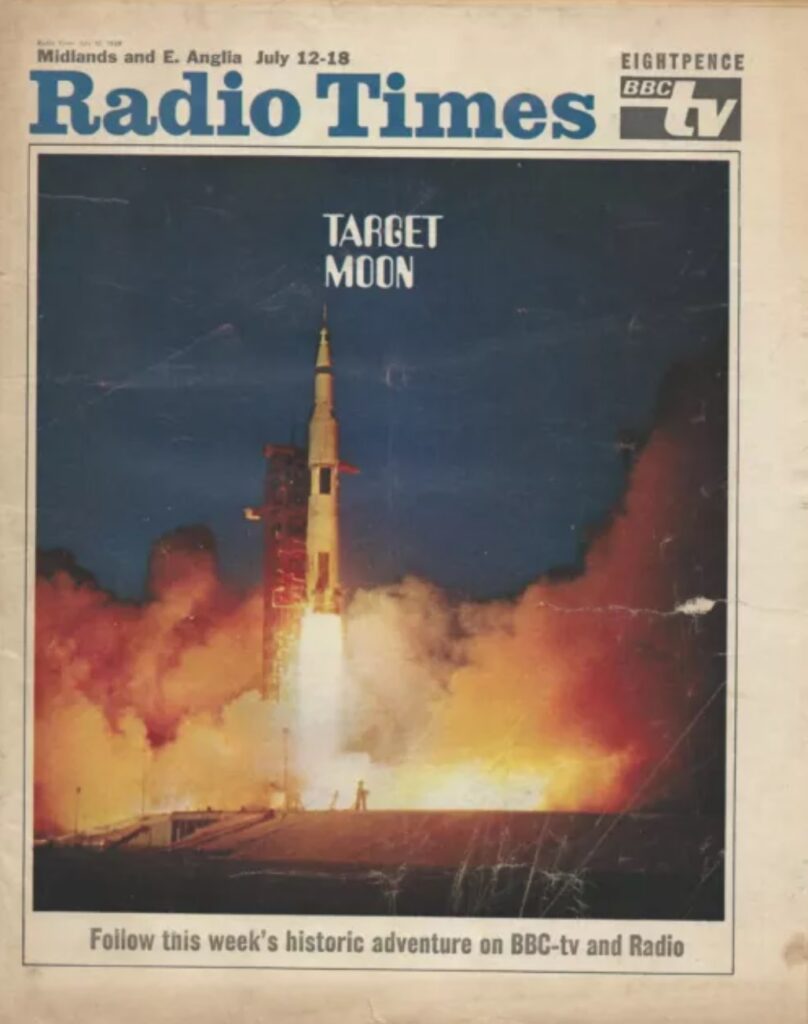

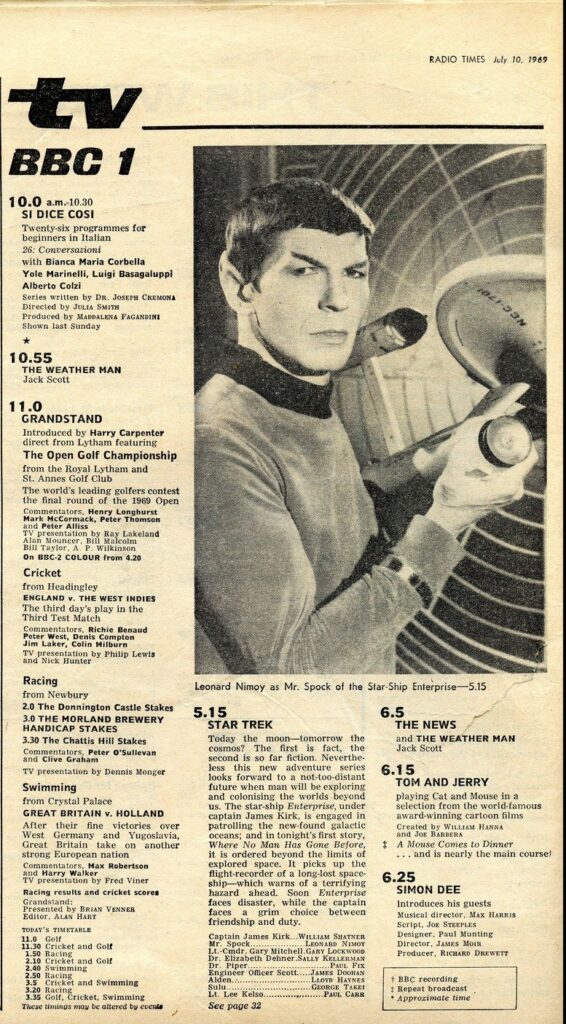

Programme description from The Radio Times, 12th July.

Programme description from The Radio Times, 12th July. Cover by Charles Platt

Cover by Charles Platt

Photo by Gabi Nasemann

Photo by Gabi Nasemann  Sketch by R. Glyn Jones

Sketch by R. Glyn Jones  Photo by Gabi Nasemann

Photo by Gabi Nasemann

![[July 22, 1969] Let The Sunshine In (More July Books)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/690722covers-672x372.jpg)

![[July 20, 1969] Today's the day! (August 1969 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/690720guide-672x372.jpg)

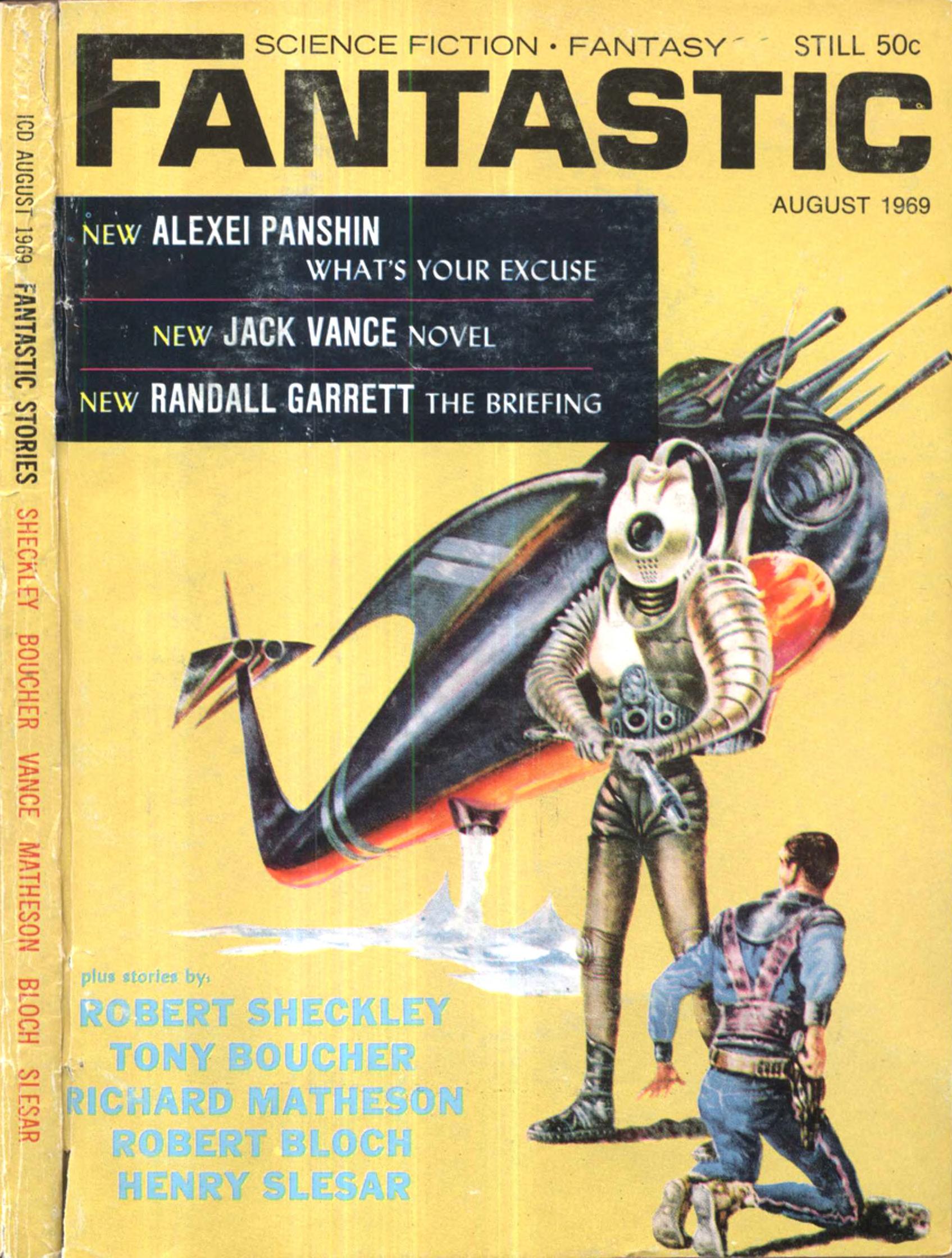

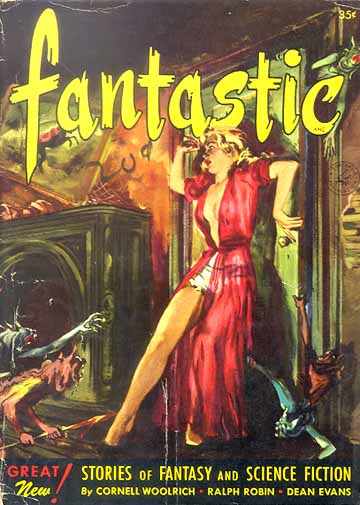

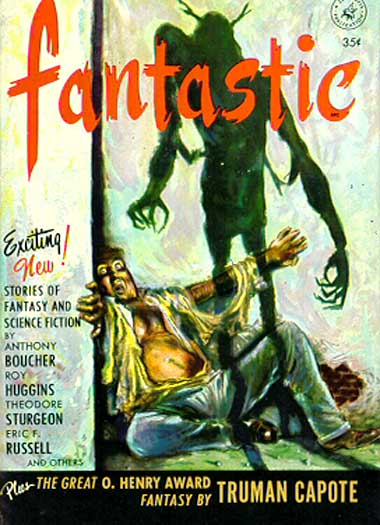

![[July 10, 1969] Sex! Now That I Have Your Attention . . . (August 1969 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/COVERSMALL-672x372.jpg)

![[July 8, 1969] Nowhere fast (August 1969 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/690708galaxycover-450x372.jpg)

![[July 2, 1969] Merging streams (August 1969 <i>Venture</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Venture-1969-08-Cover-543x372.jpg)

More geometric shapes and color washes. Art by Bert Tanner

More geometric shapes and color washes. Art by Bert Tanner![[June 30, 1969] Anywhere but here (July 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/690630analogcover-656x372.jpg)