For this month's Cinemascope, things get a little unusual. The horror scene is nothing special, even with Vincent Price starring, but you must dig the filmed play that George reviews below!

For this month's Cinemascope, things get a little unusual. The horror scene is nothing special, even with Vincent Price starring, but you must dig the filmed play that George reviews below!

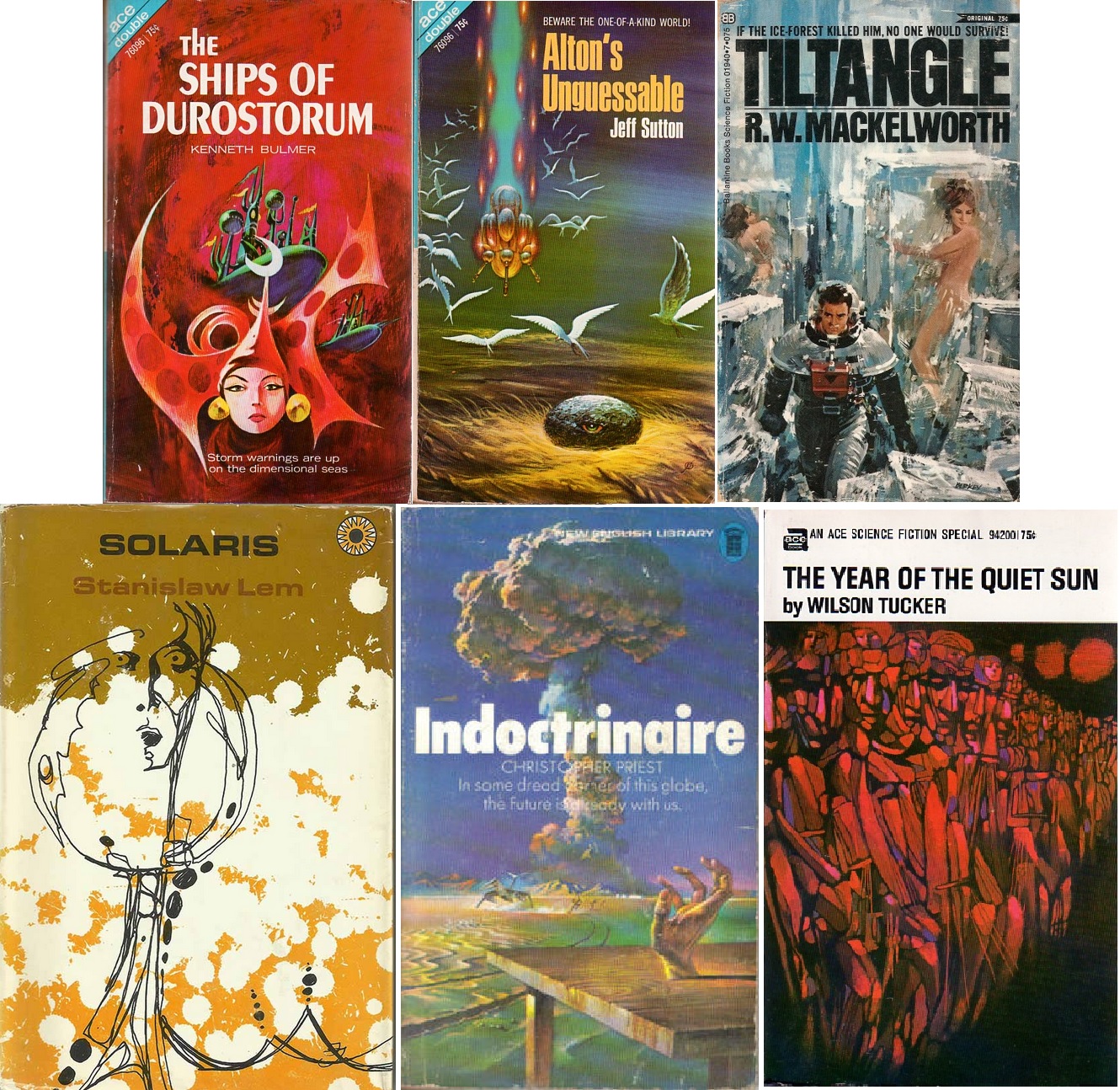

This month saw such a bumper crop of books (and a bumper crop of Journey reviewers!) that we've split it in two. This first one covers two of the more exciting books to come out in some time, as well as the usual acceptables and mediocrities. As Ted Sturgeon says: 90% of everything is crap. But even if the books aren't all worth your time, the reviews always are! Dive in, dear readers…

by Fiona Moore

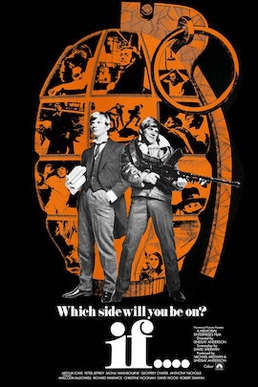

If…. is a movie which came out a couple of years ago, but is rapidly becoming a staple of the college film society scene here in the UK and overseas. It’s firmly within the satirical-surrealist tradition that characterises the likes of The Prisoner (with whom If… shares an editor, South African activist Ian Rakoff), Monty Python, and The Bed Sitting Room. The question is, how well does that stand up as time and cinematic fashion move on?

The story is set at a British all-male boarding school, where young men from the privileged classes learn the rigid, brutal, complex hierarchies and rules which will characterise their adult lives as well. Through the lens of a new arrival, we encounter a world where senior prefects enforce a rigid regime, obsessed with trivialities like hair length and permitted foods but enforcing this through corporal punishment; where younger students are forced to act as servants to their elders, with an implied sexual dimension to this servitude; where religion and the military bolster and reinforce the regime. However, the school also has its rebellious counterculture in the form of three young men, the “Crusaders”, led by Travis (played by newcomer Malcolm McDowell, whose performance here has reportedly led to Stanley Kubrick casting him in his forthcoming adaptation of A Clockwork Orange). their rebellion begins with minor acts of disobedience like growing a moustache, but grows in commitment and brutality until the climax of the story.

Continue reading [June 6, 1970] Children's Crusade: If…. (the movie, not the magazine)

by Cora Buhlert

A Cold Night in Munich

In my last article, I wrote that a feeling of hope and optimism was permeating West Germany ever since the general election last fall. Sadly, on February 13, 1970, those good vibrations were disrupted by a reminder of the darkest time of German history.

It was a cold Friday night in the Glockenbach neighbourhood of Munich. The shops on Reichenbachstraße had already closed for the night and in the Victorian apartment buildings lining the street, people were enjoying the start of the weekend.

On of the buildings along Reichenbachstraße is the Munich synagogue, built in 1931. It was the only synagogue in Munich to survive the Reichskristallnacht on November 9, 1938, because the Munich fire brigade stopped the Nazi mob from setting fire to the building, insisting that a fire would spread out of control and burn down the entire densely populated street.

After World War II, the synagogue reopened and now serves as the main synagogue for the Jewish population of Munich. The Jewish congregation of Munich also purchased an adjacent Victorian apartment building to serve as a community centre, library, restaurant, kindergarten and as a home for elderly members of the congregation and students.

Shortly before nine PM, an unknown person or persons entered the community centre, took the elevator to the top floor and spread gasoline in the wooden stairwell on their way down. Then, they struck a match, lit the gasoline and fled. The resulting fire spread rapidly through the old building.

At the time of the arson attack, fifty people were inside the community centre, celebrating the sabbath. Forty-three of them were rescued by neighbours and the Munich fire brigade. However, the fire in the stairwell had cut off access to the upper floors of the building, trapping several resident in their rooms.

Twenty-one-year-old medical student Sara Elassari, who lived on the top floor, managed to escape through the window and scramble down a drain pipe, from where she was rescued by the fire brigade. Seventy-one-year-old Meir Max Blum, who had returned from the US to his city of birth only the year before, jumped from a window and succumbed to his injuries. Six other residents aged between fifty-nine and seventy-one were found dead in their rooms. All seven victims had survived the Holocaust – some in hiding, some in exile, some imprisoned in concentration camps – only to be murdered in their homes in supposedly peaceful West Germany.

Too Many Suspects

As of this writing, we do not know who is responsible for this terrible tragedy. The Munich police are following various leads. The obvious suspects would be the far right, since West Germany has no shortage of old and new Nazis. However, there is also evidence pointing at an eighteen-year-old far left radical with a history of arson, because Anti-Semitism does not thrive only among the right.

Finally, the arson attack might also be connected to the Middle East conflict, especially since a Palestinian terrorist group had tried to hijack an El Al plane during a stopover at Munich-Riem airport only three days before. The hijack attempt failed, but one passenger, thirty-two-year-old German-Israeli businessman Arie Katzenstein, was killed and ten other people were injured, some of them critically. On February 17, another hijack attempt was foiled, also at Munich-Riem airport but thankfully without casualties. Were the same terrorists also responsible for the arson attack? So far, we don't know.

However, the sad truth remains that twenty-five years after the end of the Third Reich, eight Jewish people (the seven victims of the arson attack as well as the victim of the airport attack) were murdered and several others injured in the heart of Munich. The old venom of Anti-Semitism is back, if it ever left in the first place.

Nuclear War as Comedy

When the world outside becomes too terrible to bear, the cinema offers a respite for an hour or two. And so I headed out to see a movie that debuted at last year's Berlin Film Festival, but is only now reaching West German cinemas. And since the movie was billed as a comedy, it would seem to guarantee a good time.

Continue reading [March 28, 1970] Cinemascope: No Vacancy (The Bed Sitting Room)

by Fiona Moore

Greetings from the Island of Formosa, more usually known as the Republic of China! Though the local name for the island is “Taiwan.” I’m here on a visiting fellowship at National Tsinghua University.

The Republic is a hub of electronics and engineering, and so there is a great appetite for SFF here. SF is regarded by the nationalist government as a way of encouraging young people into careers in science, and also SF, of the “if this goes on…” variety, is seen as a vector of “moral teaching”.

Nonetheless, for the past twenty years Taiwan has lagged behind Korea in the production of locally-written SFF. Most what is available is foreign SF works like Asimov and Clarke, in (often not very good, or indeed legal) translation. In fact, some translators leave the author’s name off the novel and pass it off as theirs! The scene is further hampered by restrictions on Japanese cultural products, an understandable reaction to 50 years of Japanese colonisation but nonetheless one which denies Chinese people a wealth of movie and comic-book content.

However, there are signs of change emerging, with the rise of a thriving short SF fiction scene. The appearance of Zhang Xiaofeng’s clone story Pandora in the China Times in 1968 has led to the publication of a lot of stories in mainstream newspapers and magazines, the creation of dedicated SFF magazines, and even an SF short story contest. The government is said to be encouraging the development of a “truly Chinese” SF. Some authors to watch include Chang Shi-Go, an electronics engineer by day and writer by night, Zhang Xiguo, and Huang Hai, who is rumoured to be putting together an anthology of near-future science fiction stories.

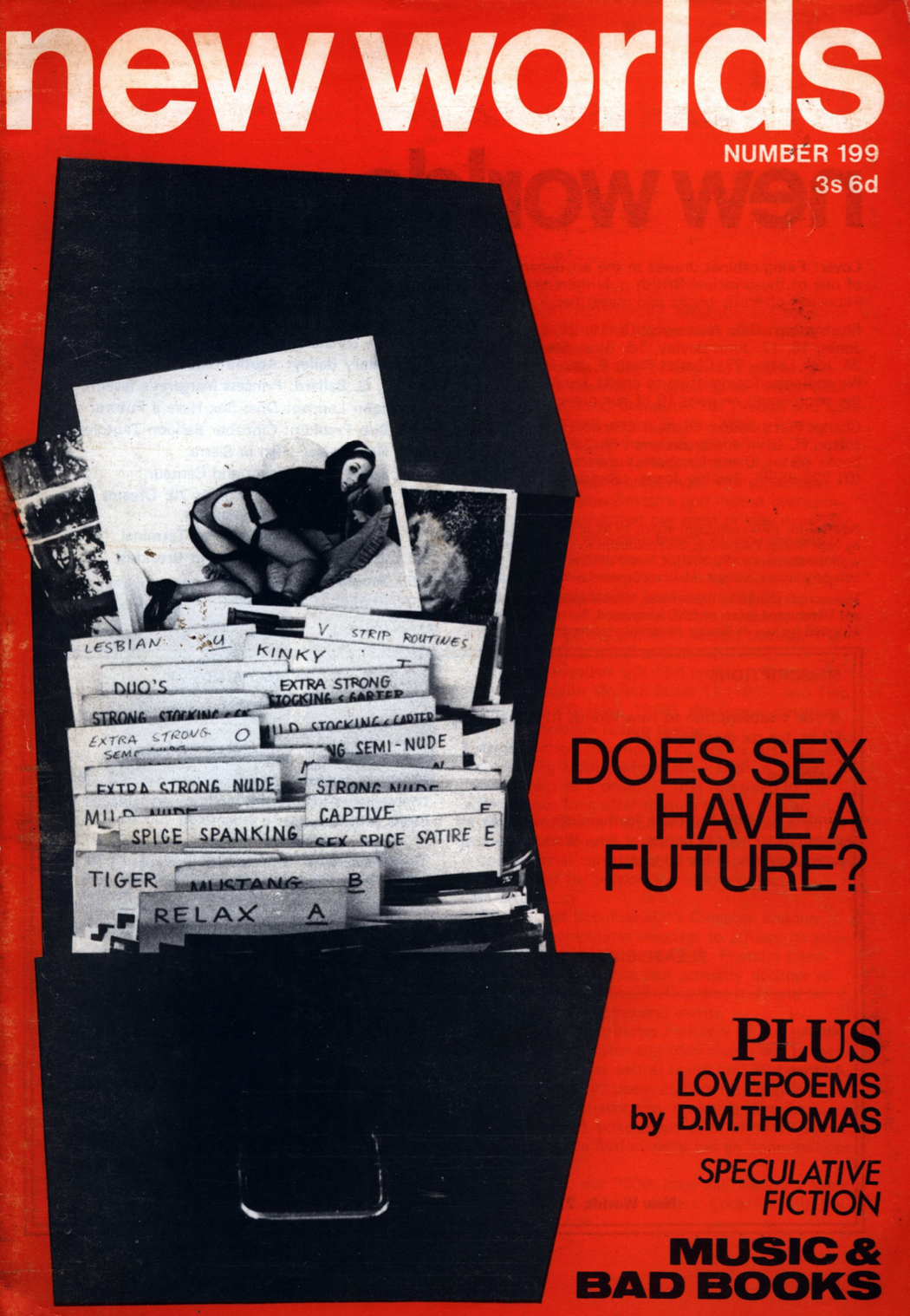

Meanwhile, my copy of New Worlds has followed me safely to Asia. It’s the 200th issue: will it mark a new direction for New Worlds, or will it be more of the same old worlds?

You can probably guess.

Cover by Andrew Lanyon

Continue reading [March 24, 1970] 200 Not Out (New Worlds, April 1970)

by Fiona Moore

This month has seen a few positive developments. In news of the former British Empire, the world welcomes the new Cooperative Republic of Guyana. Guyana (formerly British Guyana) had achieved independence in 1966, but now the country has completely severed governing ties with the U.K., exchanging a Governor General for a ceremonial President. The South American nation is also officially pursuing a somewhat socialistic path, introducing cooperative elements to the economy. May she continue to be a leading member of the Commonwealth!

Former President Forbes Burnham addresses a crowd regarding his plan for a Cooperative Republic in 1969

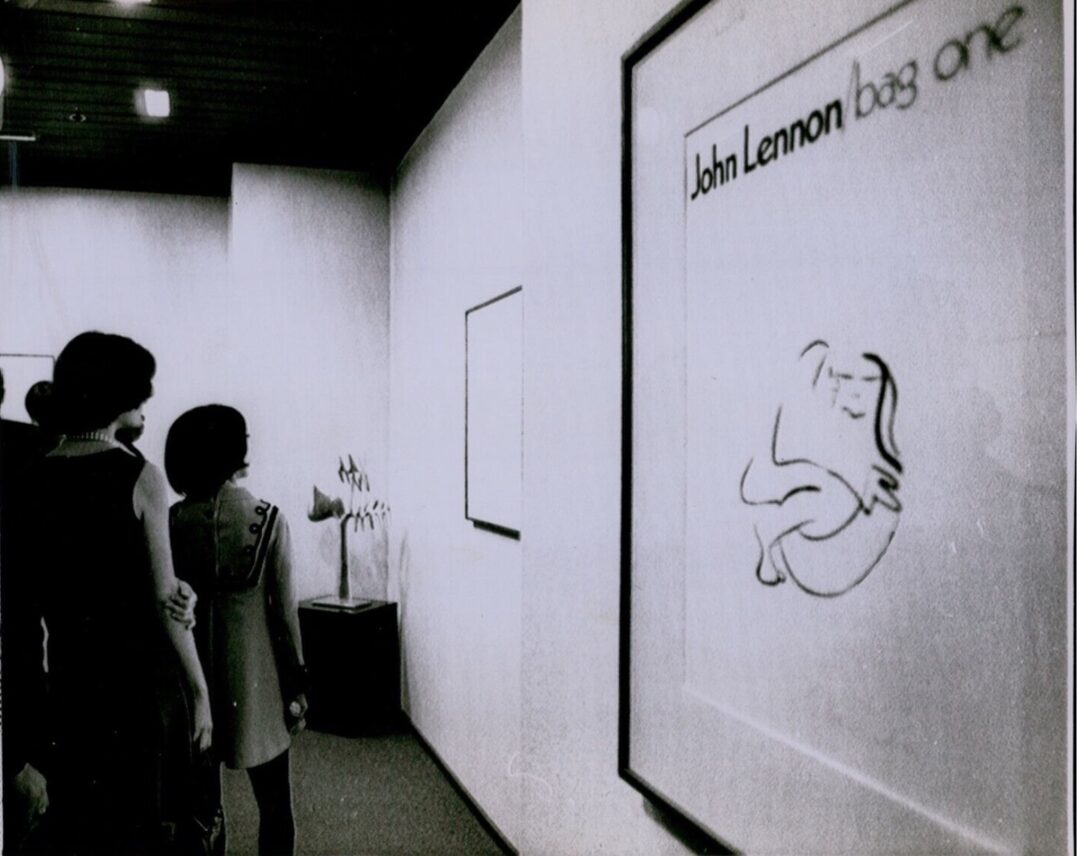

Meanwhile, Miss Ono is back in the news, as the owner of the London Arts Gallery has been charged with corrupting morals for exhibiting John Lennon’s etchings, which include lithographs of himself and his wife in coitus. I suppose we’ll get to see just how far the Permissive Society goes.

A crowd at the Gallery examines Lennon's art

Which brings us neatly to New Worlds, who seem to be courting similar controversy, or attempting to, anyway. The front cover this month is a file-box of erotic pictures with the heading Does Sex Have A Future? This gives the impression that New Worlds are trying to restore their flagging fortunes by going back to basics: shock the Tories by talking about sex.

Artist/designer uncredited

Continue reading [February 24, 1970] Sex and the Single Writer: New Worlds, March 1970

by Fiona Moore

An Evening of Edgar Allan Poe

Theatrical poster for An Evening of Edgar Allan Poe

Theatrical poster for An Evening of Edgar Allan Poe

An Evening of Edgar Allan Poe is an hour-long film in which four Edgar Allan Poe stories are recited by Vincent Price. Originally made as a television play (and in a way which suggests it was based on a theatrical production, albeit with the addition of some new visual effects), it’s reminiscent of the BBC’s A Ghost Story For Christmas segment, and I was recently asked to view it as a possible acquisition as a teaching tool by my university’s English Literature department.

The Cask of Amontillado

The programme is split into four segments, in each of which Price recites a different Poe short story. Fairly predictably, these are “The Tell-Tale Heart”, “The Sphinx”, “The Cask of Amontillado” and “The Pit and the Pendulum”. Each segment is performed with Price in character as the narrator of each story, with appropriate costuming and sets. Although Price does show a decent range in playing different characters, they’re all very much within Price’s repertoire as an actor, so, although none of the performances are bad, there are no real surprises to be had here.

The Sphinx

The Sphinx

I felt the best segment was “The Cask of Amontillado”. Price really seems to relish the role of Montressor and plays him with a wicked twinkle in his eye, surrounded by luxurious draperies and furniture and a banquet-table of food. The weakest for me was “The Sphinx,” which struggled to hold my attention, though it did have an effective use of special effects when we briefly see a skull overlaid over Price’s face at a crucial moment.

The Pit and the Pendulum

The Pit and the Pendulum

By contrast, “The Pit and the Pendulum” was a good enough dramatization of an exciting story, but the problem was that the producer seemed to feel it needed jazzing up with effects shots of Price falling into the pit, Price helpless before the pendulum, Price faced with colour separation overlay ("chroma-key" to yanks) flames, and so forth. The rats were far too cute, with inquisitive little faces and glossy fur, for me to find them horrific.

Finally, “The Tell-Tale Heart” was a good choice as the opening story, told simply with the set a bare garret, with Price steadily ramping up the hysteria as the narrator follows his path into murder and madness.

The Tell-Tale Heart

The Tell-Tale Heart

One great benefit I can see from this production is a chance to show audiences who may just know Poe from the cinematic productions loosely based on his work, just how skilled a horror writer Poe was in real life. The issue with something like “The Pit and the Pendulum” is that one can’t really get an entire 90-minute film out of it without adding a lot of material, which, while it can work as a movie, means you lose the terrifying economy of the original story (although if anyone wants to adapt “The Cask of Amontillado”, I think one could spend at least 90 minutes exploring the buildup of resentment in the two characters’ relationships that led up to the final murder). For this reason, I’m recommending that the English Literature department acquires a copy, and would also say that, if it turns up on TV in your region, it’s worth a watch.

3 out of 5 stars.

by Victoria Silverwolf

There's A Signpost Up Ahead . . .

Two films I caught recently reminded me of Rod Serling's late, lamented television series Twilight Zone. Let's take a look.

Less than half an hour long, this skiing film is the sort of thing that might be shown at a college campus, before the main feature in a movie theater, or to fill up time on television in the wee hours of the morning. The brief running time isn't the only thing that reminds me of Serling's creation.

We begin with scenes of people skiing, edited in a jumpy way. Jazz, rock, and folk music fill up the soundtrack. The skiers also fool around in the snow, eat some fruit, and so forth.

Suddenly, we see a news announcer. He tells us that scientists have determined that every subatomic particle in the universe has reversed polarity. I'm not sure what that means, but let's see what happens.

Somehow, this is supposed to change the way people perceive things. That means the film turns into a negative of itself.

This goes on for a while, then the movie goes back to normal. Once in a while, it turns back into a negative. I guess that's a Moebius Flip. Along with more skiing, we get folks at an amusement park and eating in a restaurant. This part of the film features some pretty impressive and scary scenes of dangerous winter sports. People ski over huge crevasses, wind up on top of a tower of snow, and hang from cliffs.

Is it worth twenty-odd minutes of your time? Well, if you like psychedelic images or are a big fan of skiing, it could be. The science fiction premise is just an excuse to reverse the colors of the film, and there's no real plot at all. I've never been on a pair of skis, so I can only appreciate the athleticism on display here as an outsider.

Two stars.

This is a made-for-TV movie that aired on CBS stations in the USA earlier this month. It begins with five men in World War Two uniforms standing around a wrecked American bomber of the time. They seem to be in pretty good shape, given that they're in a desert wasteland. Things get weird when we find out they've been waiting to be rescued for seventeen years.

The crew of the Home Run.

It quickly becomes clear that they are ghosts, waiting for their bodies to be found so they can stop haunting the wreck.

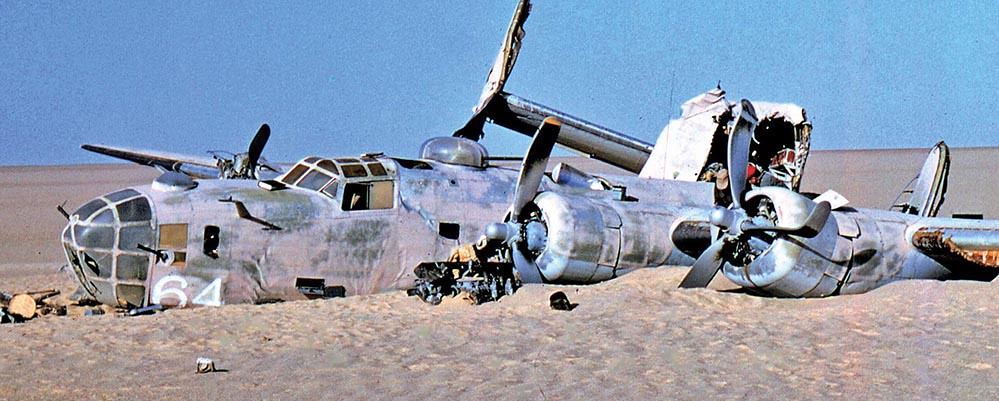

I should note here that the premise is inspired by the case of the Lady Be Good, a bomber that crashed in the Libyan desert in 1943 and was not discovered until 1958.

The real wreck.

Fans of Twilight Zone will remember the episode King Nine Will Not Return, which was also inspired by the fate of the Lady Be Good. That tale goes in a different direction, however.

Two men in an airplane discover the wreck. (By the way, the fact that the ghosts have been waiting for seventeen years means that the movie takes place in 1960 or so. There's no other indication that it's set a decade ago.)

The discoverers, who look more 1970 to me.

This leads to an official investigation by the United States Army. (Remember that the Air Force was part of the Army, and not a separate branch of the service, until a few years after World War Two.) Two officers are in charge of the mission.

William Shatner, fresh from Star Trek, as Lieutenant Colonel Josef Gronke and Vince Edwards, best known as Ben Casey, as Major Michael Devlin.

They pay a visit to the sole survivor of the Home Run. This fellow parachuted out of the plane and landed in the Mediterranean Sea, managing to make it out alive to continue his military career. (More details of what happened later.)

Brigadier General Russell Hamner, as played by Richard Basehart, recently the star of the TV series Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea.

Hamner agrees to accompany the two officers to the North African desert. He claims that all of the crew of the Home Run bailed out into the ocean, so the plane must have continued without them for several hundred miles before it crashed. Unlikely, but possible. Flashbacks tell us the real story.

Hamner as the navigator of the Home Run during the war.

The bomber was damaged in an attack by the enemy. The captain ordered Hamner to plot a course back to base, but he panicked and bailed out against orders. Without a navigator, the crew went off course and the plane crashed.

Tension builds as Devlin casts doubt on Hamner's story, and Gronke tells him not to make waves, lest he ruin his career. Both officers have their own concerns about their pasts, adding depth of character. Without giving too much away, let's just say that the truth comes out because of a harmonica, a rubber raft, and Hamner's guilty conscience. There's a powerful and poignant conclusion.

The last ghost faces an eternity playing baseball alone.

This is quite a good movie, particularly for one made for TV. I like the fact that the ghosts appear as ordinary men, rather than being transparent or something. The actors all do a good job. You'll never hear the song Take Me Out To The Ball Game again without having an eerie feeling.

Four stars.

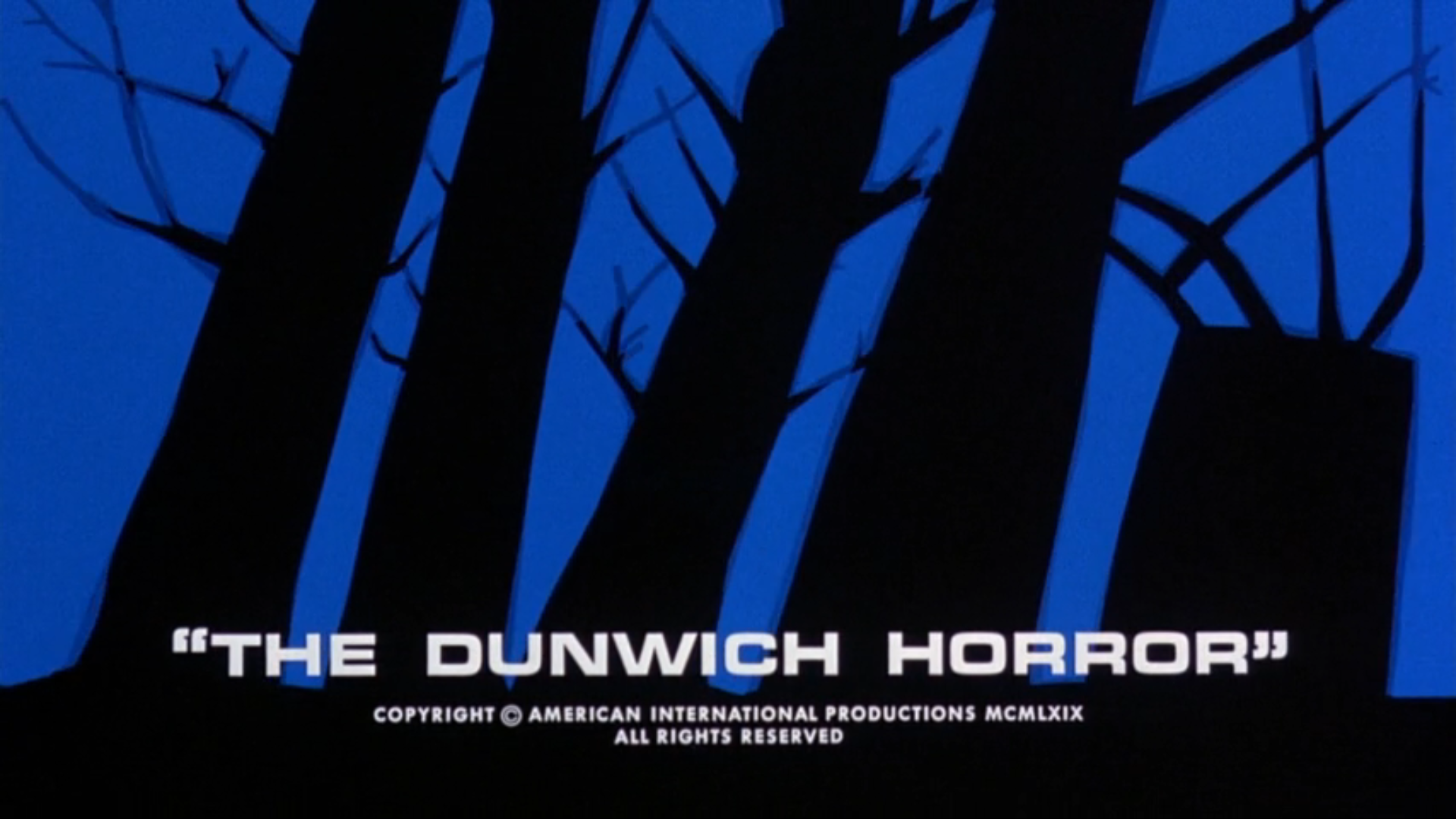

Over the past several years, AIP has adapted stories by H. P. Lovecraft for the big screen—or at least the drive-in. The results have been mixed, but they could certainly be much worse. The first and still the best of these was The Haunted Palace (adapted from The Case of Charles Dexter Ward) back in '63, directed by Roger Corman, with a script by the late Charles Beaumont, and starring an especially tormented Vincent Price. It was a very fine picture. Now we have the latest entry in this "series," The Dunwich Horror, taken from the Lovecraft story of the same name, although it's a pretty loose adaptation.

The Dunwich Horror

One warning I want to give about this movie, one which has nothing to do with sex or violence, is that, aside from being generally a pretty strange film, there are several scenes featuring flashing lights, or a color filter changing rapidly to give one the impression of a strobing light. Some people (thankfully not many) are susceptible to epileptic fits if subjected to such stimuli.

Now, as for the film itself, once we get past what I was surprised to find is an animated (as in a cartoon) opening credits sequence, we start with what seems to be a flashback of a woman giving birth, surrounded by two elderly sisters and an old man. We then flash forward to Miskatonic University, that college of the occult and Lovecraft's making, in Arkham. Nancy Wagner (Sandra Dee) is a student who, in the college's library, meets a good-looking but unusual young man named Wilbur Whateley (Dean Stockwell), who is terribly interested in the Necronomicon. I'm sure his interest in the accursed book and his strange deadpan way of talking are perfectly innocuous. A certain professor at Miskatonic, Henry Armitage (Ed Begley), gets a bit of a hunch that Wilbur is up to no good, but for now does nothing about it.

"The Dunwich Horror" is one of Lovecraft's most celebrated stories, but it's also one of his trickiest. As with "the Call of Cthulhu," Lovecraft wrote "The Dunwich Horror" as if it were a report or an essay, a work of journalism or academia, rather than a fiction narrative. There's no protagonist, properly speaking, although Wilbur is certainly the story's nucleus. This remains sort of the case with the film, although Nancy and Armitage now serve as our eyes and ears, or rather as normal people in what becomes an extraordinary situation. However, it's not Sandra Dee or Ed Begley who caught my attention, but Dean Stockwell as Wilbur, who gives almost what could be considered a star-making role (to my knowledge his most high-profile roles up to now were film adaptations of Sons and Lovers and Long Day's Journey into Night), if not for the movie that surrounds him. Unlike his short story counterpart Wilbur here is not physically deformed, but instead talks in a strangely deadened tone, as if human emotions are foreign to him. Stockwell as Wilbur manages to be uncanny simply through how he talks and acts, which is a major point of praise.

Director Daniel Haller and his team of screenwriters have opted to streamline Lovecraft's story while giving it a sort of romance plot, as well as a dose of sex and violence. Sex and Lovecraft have always been uneasy bedfellows, even in something like "The Shadow Over Innsmouth" which explicitly involves sex in its plot. Wilbur is one of two twins, the other having supposedly died in childbirth, with the father being unknown, and his mother having been kept in an asylum for the past two decades. Wilbur lives with his grandfather, Old Man Whateley (Sam Jaffe, who some may recognize as that one scientist in the now-classic The Day the Earth Stood Still), who seems convinced his grandson is also up to no good, but arbitrarily (the film does nothing to explain this) does nothing about Wilbur being a scoundrel. For his part, Wilbur sees Nancy as a pretty fine girl—for a dark ritual, that is. The idea is that if he can steal the Necronomicon and impregnate Nancy (the implication, via a mind-bending scene, is that he rapes her), he can bring one of "the Old Ones" into the human world.

As this point the plot splits in two, with one half focusing on Wilbur and Nancy's "romance" while the other sees Armitage tracking down the mystery of Wilbur's birth, since it becomes apparent the young man and the Necronomicon are somehow connected. One of the strangest (sorry, "far-out") scenes in the whole movie is when Armitage goes to see Wilbur's mother (Joanne Moore Jordan), who apparently had lost her mind many years ago upon giving birth to Wilbur and his dead twin. When it comes to this movie, there are two types of strange: that of the unnerving sort, and that of the cheesy sort. There are parts (sometimes moments within a single scene) of this movie that do a good job of spooking the audience, and others where it's rather silly. With that said, the nightmarish effect of Jordan's performance combined with the changing color tints in this scene make it one of the most effective. This is a movie that generally shines brightest when it focuses on Stockwell's performance and/or the Gothic cliches (including a creepy old house) that clearly also influenced Lovecraft's writing. Maybe it's because they didn't have the budget for it, but the lack of an on-screen monster for the vast majority of the film's runtime also works in its favor.

When Old Man Whateley finally decides to take action, Wilbur kills him for his troubles, along with imprisoning one of Nancy's friends and turning her into some kind of abomination. Meanwhile Wilbur gives his grandfather a heathen burial and in so doing provokes the wrath of the Dunwich townspeople, who never liked the Whateleys anyway. It's revealed, or rather speculated, that Wilbur's twin may not have died after all, but instead gone to the realm of the Old Ones while Wilbur got stuck on Earth as a human. Armitage and the townsfolk succeed in stopping Wilbur from completing his ritual with the unconscious Nancy, Armitage being well-versed enough in the Necronomicon to use the book against Wilbur, killing him with a blast of lightning. So the last of the Whateley men is dead. Unfortunately, the final shot, eerily showing a fetus growing inside Nancy (which is odd, because she's probably only been pregnant a day or two), implying an Old One may be born after all.

Lovecraft purists will surely be much disappointed with this movie, and even as someone who is not exactly a Lovecraft fan, I have to admit it's by no means perfect. Even at 90 minutes it feels a bit overlong, and it tries desperately to contort one of Lovecraft's more unconventional stories into having a three-act structure. I also get the impression that the addition of blood and breasts was to appease those (people my age and younger) who are suckers for AIP schlock. Not too long ago we had Roger Corman's so-called Poe cycle, which for the most part did Edgar Allan Poe's (and in one case Lovecraft's) fiction justice on modest budgets. I would say The Dunwich Horror is on par with one of the lesser of Corman's Poe movies.

A high three stars.

[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!

by Fiona Moore

February’s rain and sleet freeze the toes right off the feet, as Flanders and Swann once sang. Still, there’s reason to celebrate: the Family Law Reform Act has come into effect, reducing the age of majority from 21 to 18 for most purposes, homosexual sex being a notable exception. Decimalisation continues apace, with the half-crown coin being taken out of circulation (don’t worry, you can exchange it at most banks).

Term has resumed at Royal Holloway College and my students are attacking the writings of Margaret Mead with their usual enthusiasm. However, there is also widespread unease among our Nigerian foreign student community over the capitulation of Biafra: many of them have had no news of their families, and are also concerned about when they will be able to go home. The university is rallying round to make sure everyone is housed, and there are jobs aplenty in Southwest London if they need to stay a while, but it is still an anxious situation for them.

Jubilant street scene in Lagos upon the news of surrender, January 12, 1970

No news of Yoko Ono after December’s festive anti-war campaign. Rumour has it she and her husband have gone off to New York for some reason, so I expect I’ll be covering her activities less often. What all this means for her husband’s band, I’m not sure.

On to New Worlds, which continues its trajectory back to being an SFF magazine, but unfortunately almost every story is suffering from a lack of originality this month.

Cover by Roy Cornwall

Cover by Roy Cornwall

Lead-In

Mostly introducing new writers and illustrators to the magazine, as well as showcasing the pieces by Ballard and Watson, and drawing the reader’s attention to a new, presumably ongoing, feature of the publication—of which, more later.

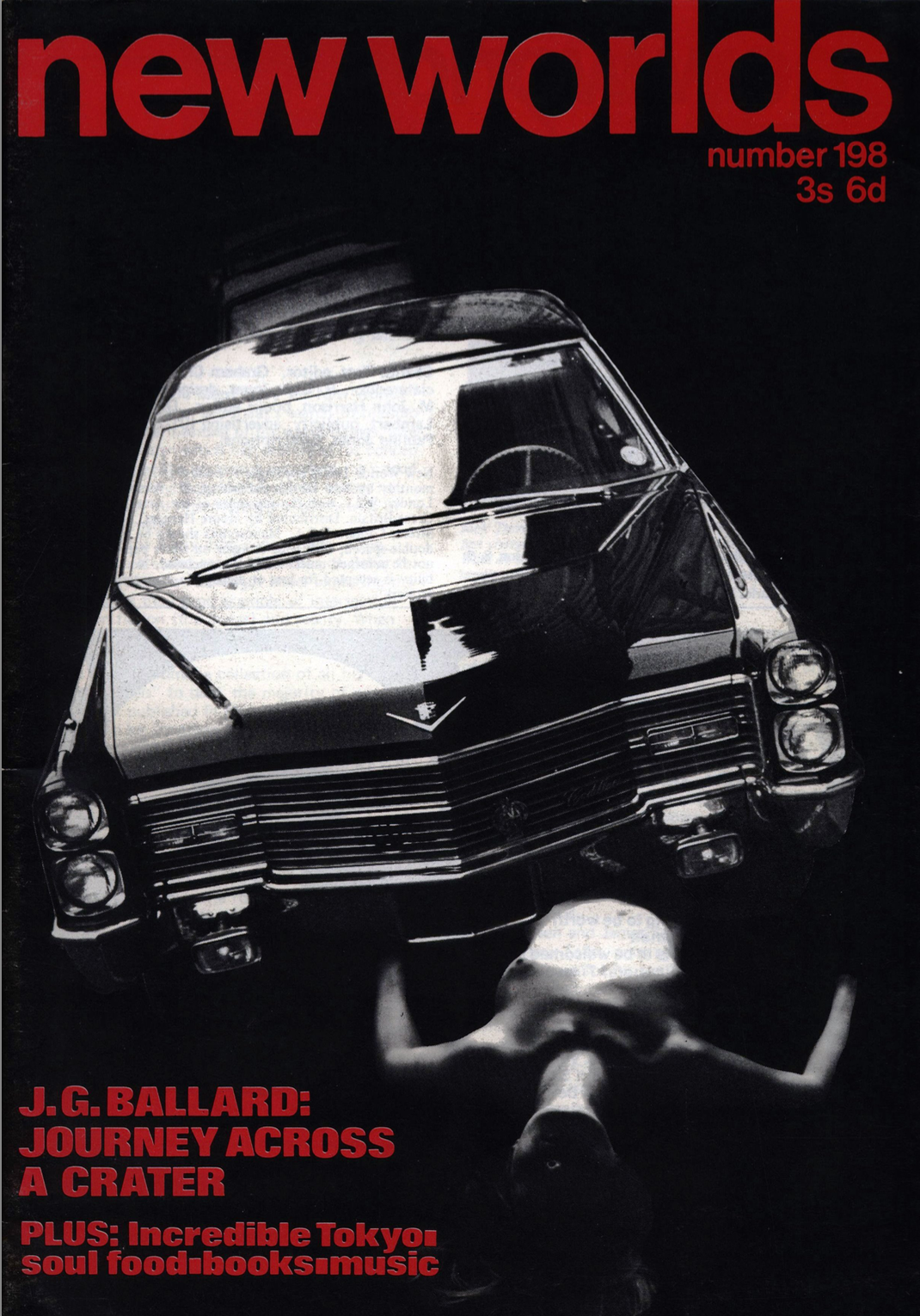

Journey Across a Crater by J.G. Ballard

A piece about a crash-landed astronaut finding his way to civilisation. There are resonances with Ballard’s earlier story “You and Me and The Continuum” (Impulse Magazine 1:1, 1966), and also some vivid sexual imagery about car crashes, which makes sense given that the Lead-In tells us Ballard is currently working on a novel about these. Interesting enough as a revisitation of familiar Ballard themes but no new ground broken. Three stars.

Soul Fast by Gwyneth Cravens

Illustration, artist uncredited (possibly Charles Platt)

Illustration, artist uncredited (possibly Charles Platt)

A story by a woman in New Worlds is always worth remarking on, particularly a woman who is a current editor of the New Yorker. However, I can’t help but notice that women writers in New Worlds always seem to get pigeonholed into writing about domestic or otherwise nurturing themes. This one, for instance, is about food and the role it plays in relationships. There are some interesting satirical commentaries on race and how over-privileged White Americans with superficial attitudes towards spirituality crib from Black and Asian cultures, which makes it worth checking out. Four stars.

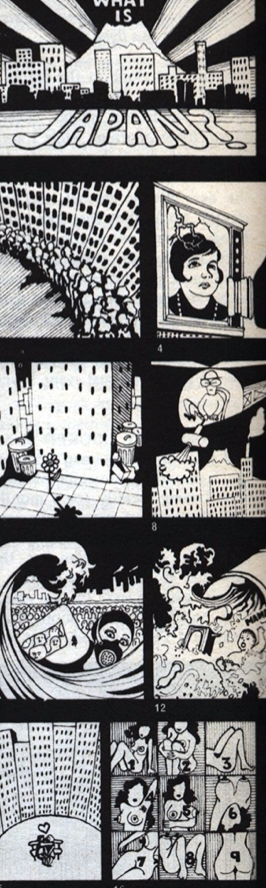

Japan by Ian Watson

Illustration by Judy Watson

This is the standout piece of the issue. Watson, a Tokyo resident, introduces Japan to English readers in a surreal, outré travelogue emphasising the weird SF-ness of living in a country where the atmosphere isn’t breathable, earthquakes and fires are endemic, sexual fetishes are catered to in the mainstream media, and consumerism takes on the status of art. The illustrations are by Watson’s wife Judy. It’s beautifully written, though, having been to Japan once or twice myself, I worry that it’s over-emphasising the strangeness of the country to a point where it might simply confirm Europeans’ stereotype that the East is a bizarre and hostile place. Nonetheless, five stars.

Apocrypha by D.M. Thomas

A poem about the life of Jesus. It’s not terribly original, but I did find it engaging and nicely written. Three stars.

6B 4C DD1 22 by Michael Butterworth

Illustration by Alan Stephanson

Illustration by Alan Stephanson

Another not-terribly-original piece in the vein of “let’s drop acid and describe the resulting trip as an SFF story.” The mind-altered protagonist lurches back and forth between several different realities, some more surreal than others, with recurring characters playing different roles. I like Butterworth’s way with prose, and some of the metaphors and descriptions are genuinely arresting, but I’d like to declare a moratorium on anyone using Alice in Wonderland as an acid trip metaphor; it’s been done to death. Similarly, while I really like the accompanying art, it looks exactly the same as every other set of illustrations intended to show an acid trip (see above). Four stars.

A Spot in the Oxidised Desert by Paul Green

Illustration by John Bayley

Illustration by John Bayley

A short prose poem from the point of view of a dying sentient tank in a future desert battlefield. Possibly the most innovative piece this issue. Four stars.

The Bait Principle by M John Harrison

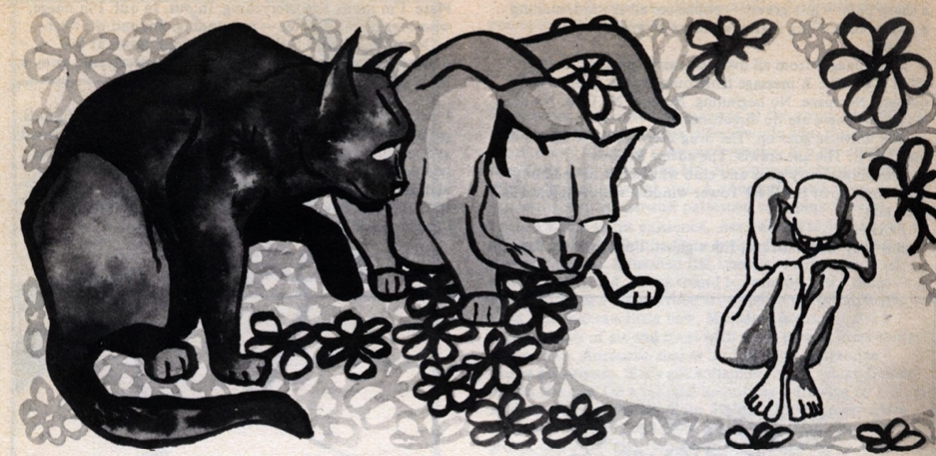

Illustration by Ivor Latto

Illustration by Ivor Latto

Patients in an asylum begin to share each other’s delusions, and, in doing so, bring them into reality, leading to an ailurophobe being tormented by human-sized cats. This is an amusing twist on the familiar crazy-people-are-actually-seeing-the-truth genre, but at the end of the day that’s all it is. Two stars.

The Wind in the Snottygobble Tree: Conclusion by Jack Trevor Story

Illustration by Roy Cornwall

Illustration by Roy Cornwall

Finally this serial lurches to an end, with some heavy-handed satire about the Catholic and Scientologist churches, spies and the police. I have the feeling that the story-so-far summary is in fact retroactively adding elements, but I’m not interested enough to go back and find out. The eponymous tree finally appears (it's a species of yew, apparently), but I don’t think it’s got much to do with the story apart from being a bit gross. One star.

A Vid by James Sallis

A short poem which didn’t really do much for me. Two stars.

Books

By Mike Walters, John T. Sladek and Douglas Hill. There’s a delightfully excruciating pun on the first page, although Walters has to contort his review in order to fit it.

Music

As regards the new feature I mentioned above: New Worlds now has a music column! This is certainly a welcome innovation, and I look forward to seeing whether the New Wave has a particularly distinctive take on album reviews.

Overall, I’d say the magazine is suffering this month from a lack of originality. Everything is competently written at worst and sometimes really beautiful, but most of it is things that have been done before. Even the music column is something we see over and over in other magazines, and whether the fact that the reviewers are from the usual New Worlds crowd will make a difference is uncertain.

Is the New Wave played out? Can it (and Mr. Yoko Ono’s musical career) survive into the new decade? Time will tell.

[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!]

by Fiona Moore

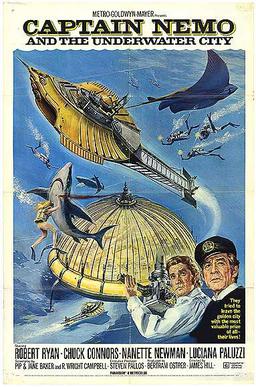

Captain Nemo and the Underwater City

I had low expectations for Captain Nemo and the Underwater City, thinking it would be a bit of enjoyably fluffy escapism. For the most part this is true, but it does have a few things to recommend it beyond that.

Poster for Captain Nemo and the Underwater City

The Nautilus rescues a small band of survivors from a shipwreck, and takes them to, yes, an underwater city founded by Captain Nemo (Robert Ryan) called Templemer (everyone pronounces it Temple-mere, which makes it sound like a small town in the Home Counties or possibly a plantation in the Old South). They include a plucky and intelligent widow (Nanette Newman) with a young son (Christopher Hartstone), a rugged-faced American senator (Chuck Connors), two comedy Cockney wide-boys (Bill Fraser and Kenneth Connor), a cute and suspiciously well-behaved kitten (name unknown), and an engineer who is clearly about to go over the edge of sanity (Allan Cuthbertson).

Templemer is a utopian community where food and drink and education are free, everyone lives their best lives, and gold is as common as steel is for us. At this point I rolled my eyes, expecting that the surface people would all decide that There’s No Place Like Home and plot to escape this perfectly decent hippie paradise; however, in fact, the newcomers are divided on that point, and their reasons for wanting to leave or stay are all in character and plausible.

Nemo's guests are less than thrilled at their accommodation.

Nemo's guests are less than thrilled at their accommodation.

The movie explores the frequently-asked question of our time: whether it’s better to engage with the problems of society or just to tune in, turn on and drop out, building a better world outside instead. Nemo and his cohorts have definitely chosen the latter, while Senator Fraser’s reason for wanting to return to the surface is to do the former. The story explicitly takes place at the time of the American Civil War, and Nemo has undergone an ethnic shift to become an American. This gives the implication that Nemo is rejecting his own country’s troubles by retreating to Templemer and, consequently, inviting comparisons with the modern USA (and with Ryan himself, well known as a pacifist and an outspoken critic of the American government). Although the movie seems to want us to side with Senator Fraser, I personally remain unconvinced.

There's also some nice modelwork, even if it's often hard to see.

There's also some nice modelwork, even if it's often hard to see.

Of course, there are a lot of preposterous things that are overlooked or else are simply there to drive the story along. There’s a giant manta ray for our heroes to fight, which I suppose is a change from the usual giant squid. There’s only the briefest explanation of where Templemer’s population come from. The engineer’s mental collapse is so heavily telegraphed that I kept wishing someone would try and help the poor man rather than let him become another plot complication. There’s also a very long and very boring sequence where Nemo shows his guests around Templemer’s undersea farming setup, which contributes little to the story and isn’t particularly engaging and mostly seems to be there to show off the fact that MGM spent money for an expensive and complicated underwater shoot.

In short, I wouldn’t urge you to rush out and see it, but if it’s on at your local cinema and you have time to kill during the holidays, you could do worse. Two and a half stars.

by Jason Sacks

Marooned

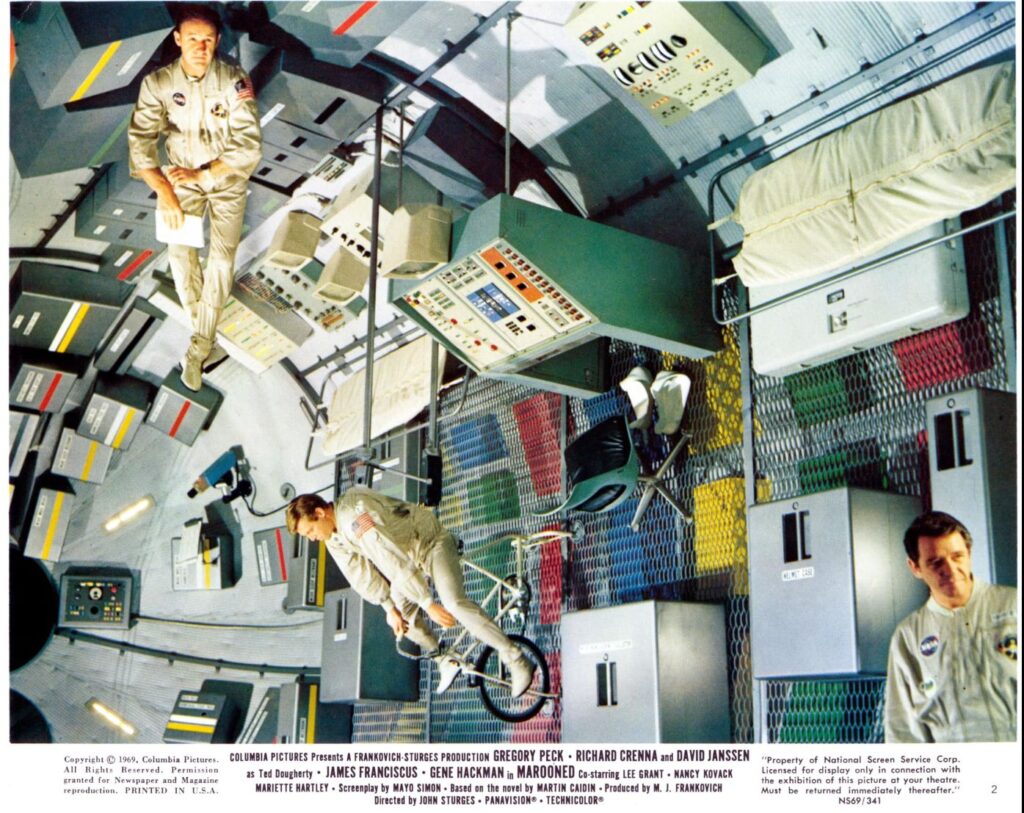

What if the real heroes of NASA weren’t the astronauts but instead the ground crew? What if the astronauts were all either bland or jerks, while Mission Control were all brave, steadfast problem solvers to a man? What if a movie with those premises promised a thrilling story but delivered leaden action?

Imagine that movie, and you’ll get something like Marooned, a new film from director John Sturges seemingly released to capitalize on America’s fascination with the space program and our incipient worries about space failures. We might expect Marooned to be a thrilling and au courant film about man's perils in space. But Marooned is more concerned with the men on the ground than the men in space. That fact helps make for a slow trudge of a film.

As the film begins, three astronauts played by Richard Crenna (The Real McCoys, Slattery's People, The Sand Pebbles), James Franciscus (The Investigators) and Gene Hackman (Hawaii, Bonny and Clyde) have completed their assignment to spend several months working in an orbiting laboratory. As the pilots begin their efforts to return to Earth, however, they find the thrusters malfunctioning on their rocket. It will take a heroic effort from the ground crew, led by Gregory Peck (needs no introduction) and David Janssen (The Fugitive), to return the astronauts to Earth. But will that dedicated crew succeed before oxygen runs out in the space capsule? And how will a hurricane at Cape Kennedy affect the rescue efforts?

It's an intriguing narrative for a movie (not to mention a book), and it's certainly very on-target for our country’s current obsessions. Marooned had the promise to be something pretty special; instead, it is a conservative, hide-bound, badly-acted failure.

Much of the film’s failure comes from an odd decision by the filmmakers: instead of focusing on the astronauts, the film spotlights their ground crew, particularly the efforts of their brave leader, Gregory Peck, to save the spacemen. In theory this could be a logical approach to the story which harnessed celebrity charisma to add seriousness to the rescue effort. Peck is a longstanding, proven screen presence. He gives the film a feeling of gravitas. But, come on, film fans: would you rather watch Gregory Peck struggle though rescue contingencies or spend more time with the astronauts trying to come up with plans? Without Cronkite (or even Chet and David) to spice things up, I can't imagine an audience is interested in watching the efforts of a bunch of white-shirt-and-tie men reading long lists of protocols off checklists, scene after tedious scene.

All that focus on protocols makes the film feel slow. But that very same slowness feels like a deliberate approach to the story. This is a workmanlike film which focuses on the amazing power of bureaucracy to solve complex problems. Solving these problems takes time, and it’s important to be able to be systematic and mark important items off a checklist. If only this movie had been cut to a crisp 90 minutes, the filmmakers’ gambit might have worked. Instead, Marooned is sluggish.

Peck seems to phone his role in. The intended gravitas from his role comes across more as torpor than as professionalism. Janssen and Franciscus bring their usual decent TV-level acting to their roles. But Hackman is especially badly selected for his role – his character, Buzz Lloyd, is impulsive and self-centered. Viewers grow tired of Buzz's histrionics and wonder how in the world someone like that made it through astronaut school. It's surprising to see Hackman perform so poorly after he recently delivered fine performances in Bonnie and Clyde and Downhill Racer, so hopefully this was just an anomaly. With his rugged good looks, Hackman looks more like a cop than an astronaut.

The film offers viewers a few small moments with the astronauts' wives. Those moments perhaps convey the most sense of the astronauts' peril, since the wives are allowed to actually emote. Veteran actresses Lee Grant (Peyton Place, In the Heat of the Night), Mariette Hartley (Star Trek: All Our Yesterdays) and Nancy Kovack (Star Trek: A Private Little War) have all done good work in the past. Here they are called upon to do little more than look concerned and show a little attitude. The actresses actually execute their assignments with aplomb. I especially enjoyed Kovack's frustrated resignation about the life she signed up for as the wife of an astronaut. She conveys a lot in small gestures and facial expressions.

The ending, again slow, is genuinely captivating nonetheless, and takes a few surprising twists. I became very invested in this film in its last 20 minutes and wish we had more scenes like these. Though it was a bit hard to root for these dull men to be rescued, the attention to detail around astrophysics and international cooperation were stellar.

John Sturges is usually an excellent director of action movies – see Bad Day at Black Rock, The Magnificent Seven or The Great Escape. But he probably shouldn’t have journeyed into space with our boring astronauts. Marooned just never comes alive like The Magnficent Seven did: the characters never popped, the action never coruscated, and the direction lacked flash.

But there’s a deeper problem here as well. One of the reasons The Great Escape was such a smash hit was that many viewers could see themselves in the zealous Steve McQueen, endlessly looking to escape his prison life. McQueen’s Virgil Hilts felt like a counterculture hero on the run, not dissimilar to the characters in Easy Rider or Bonnie and Clyde. But Marooned is a conservative, conventional movie. Its message is to trust the government, pray for the best to happen, and follow rules. Marooned is a film for Nixon’s Silent Majority and feels woefully out of place next to this year’s big hit films like Butch Cassidy, Midnight Cowboy, and Goodbye, Columbus.

Two stars.

by Fiona Moore

Here it is, nearly 1970! What does the UK have to look forward to in the next decade? Already we’ve got a new Doctor Who, a new all-live-action series from the Andersons, and a new currency is coming in. I hope we’ll join the common market and help build a revived Europe. I for one am feeling optimistic.

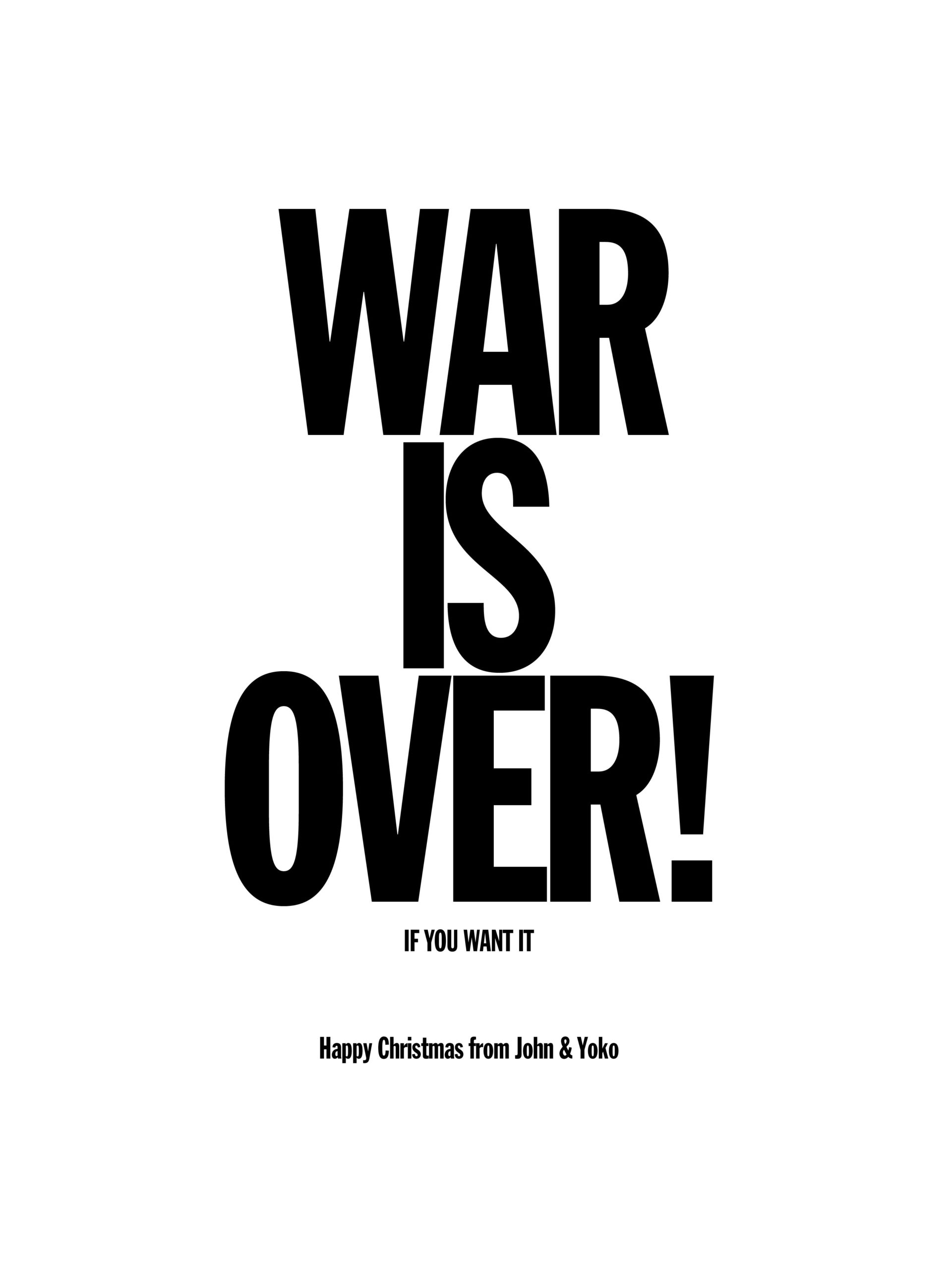

Meanwhile, what is my favourite provocative pop artist up to? Miss Ono and her husband have launched a festive anti-war campaign, with a giant poster in Piccadilly Circus (and eleven other cities around the world) reading WAR IS OVER IF YOU WANT IT. It makes a change from adverts for American soft drinks and I appreciate the sentiment.

None of the photos I took turned out, but here's the art for the poster.

None of the photos I took turned out, but here's the art for the poster.

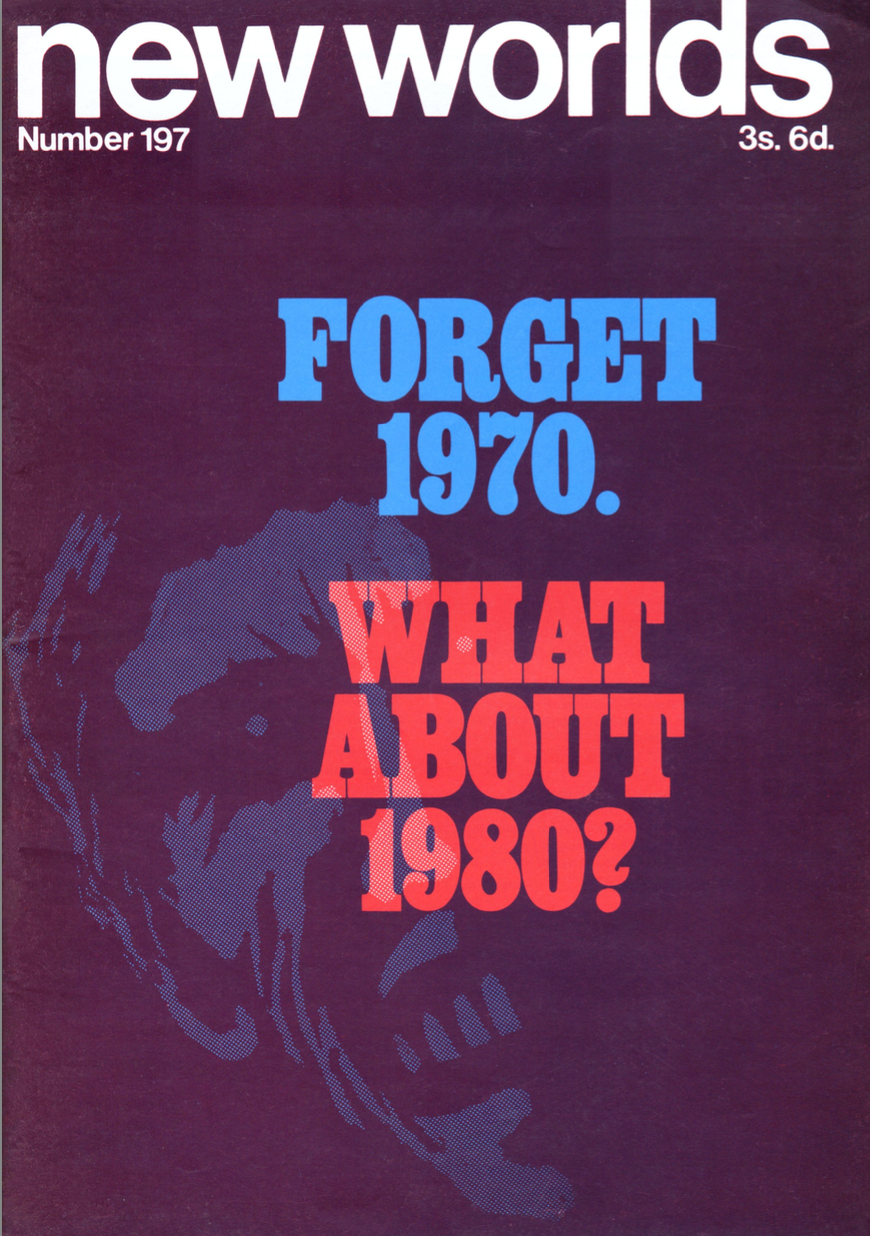

On to New Worlds. Who are making up for the last couple of issues by giving us some actual SF, with actual illustrations. There’s even a story by a woman! It’s not Pam Zoline though; she’s contributing to this issue, but as an illustrator not a writer. I’ll take what I can get.

Cover by R. Glyn Jones.

Cover by R. Glyn Jones.

Lead-In

Saying (rightly) that the media is overwhelmed with predictions of 1970, which are becoming “as dull as the next moonshot” the editors are celebrating their theme of looking forward to 1980. How many (if any) of the stories actually follow the theme? Let’s find out!

Michael Butterworth: Concentrate 3

Illustration by Charles Platt.

Illustration by Charles Platt.

A very short prose piece followed by a poem. I like the imagery of an astronaut freaking out with the feeling of stars crawling over his face but otherwise it seems to read like several opening lines mashed together. Nothing to do with 1980. Two stars.

Graham Charnock: The Suicide Machines

Illustration by R. Glyn Jones, who gets everywhere this issue.

Illustration by R. Glyn Jones, who gets everywhere this issue.

A more developed imagining of a near-future Britain, in an Oxford which has been given fully over to tourism by dull and tedious businesspeople, with “feedies”, a sort of android, as guides and entertainers. Jaded with sex, they seek instead to force the feedies to commit suicide for their pleasure. No indication that this takes place in 1980. Three stars.

R. Glyn Jones: Two Poems, Six Letters

As the title says. Two quatrains, containing only six letters. Not sure the experiment does all that much. Nothing to do with 1980. One star.

Ed Bryant: Sending the Very Best

A fun short piece about near-future man buying a holographic sensory-stimulation greeting card, which leaves the reader wondering wickedly about the recipient and the occasion. Nothing to do with 1980. Four stars.

Hilary Bailey: Baby Watson 1936-1980

Photo by Gabi Nasemann.

Photo by Gabi Nasemann.

This is one of the standout stories for me this issue, if one of the least SF (though one of the only ones to involve 1980). It’s a story in the Heat Death of the Universe vein, making the familiar strange by looking at the lives of ordinary women, with the same surname and born in the same year. It’s a sad story for me, highlighting the way in which the scientific and creative potential of women is squandered on a world not yet ready to accept them as equals. Five stars.

Harlan Ellison: The Glass Teat

Design by unknown artist.

Design by unknown artist.

Ellison saves himself some work by writing his usual TV column, but as if it were 1980. Although I wouldn’t have known that if the Lead-In hadn’t told me. It’s a 1980 where the US is at war in various developing nations, has a liar for a President, and is subject to rampant acts of terrorism at the hands of its own citizens. I suppose it’s a “if this goes on…” piece. Two stars.

John Clark: What is the Nature of the Bead-Game?

Photo by Roy Cornwall.

Photo by Roy Cornwall.

An experimental essay, containing 25 statements and questions the writer apparently posed at the 1969 Third International Writers’ Conference. The aim appears to be the usual New Worlds trick of juxtaposing sentences and having the reader discern meaning from the juxtaposition. Nothing to do with 1980. Three stars.

Michael Moorcock: The Nature of the Catastrophe

Nice to see Jerry Cornelius back with us, though I confess after the efforts of other writers Moorcock’s original version is a little disappointing. Too few descriptions of Jerry’s clothes, I think. There’s a brief mention of 1980 in order to keep this in with the theme, though there are also brief mentions of 1931, 1969, 1970, 1936 and many other years. Otherwise it’s just your usual Cornelius stuff. Two stars.

Thomas M. Disch: Four Crosswords of Graded Difficulty

Not really my favourite Disch (ha ha) of the year. Experimental poems; the first one made me laugh but the others seemed not very interesting. Nothing to do with 1980. One star.

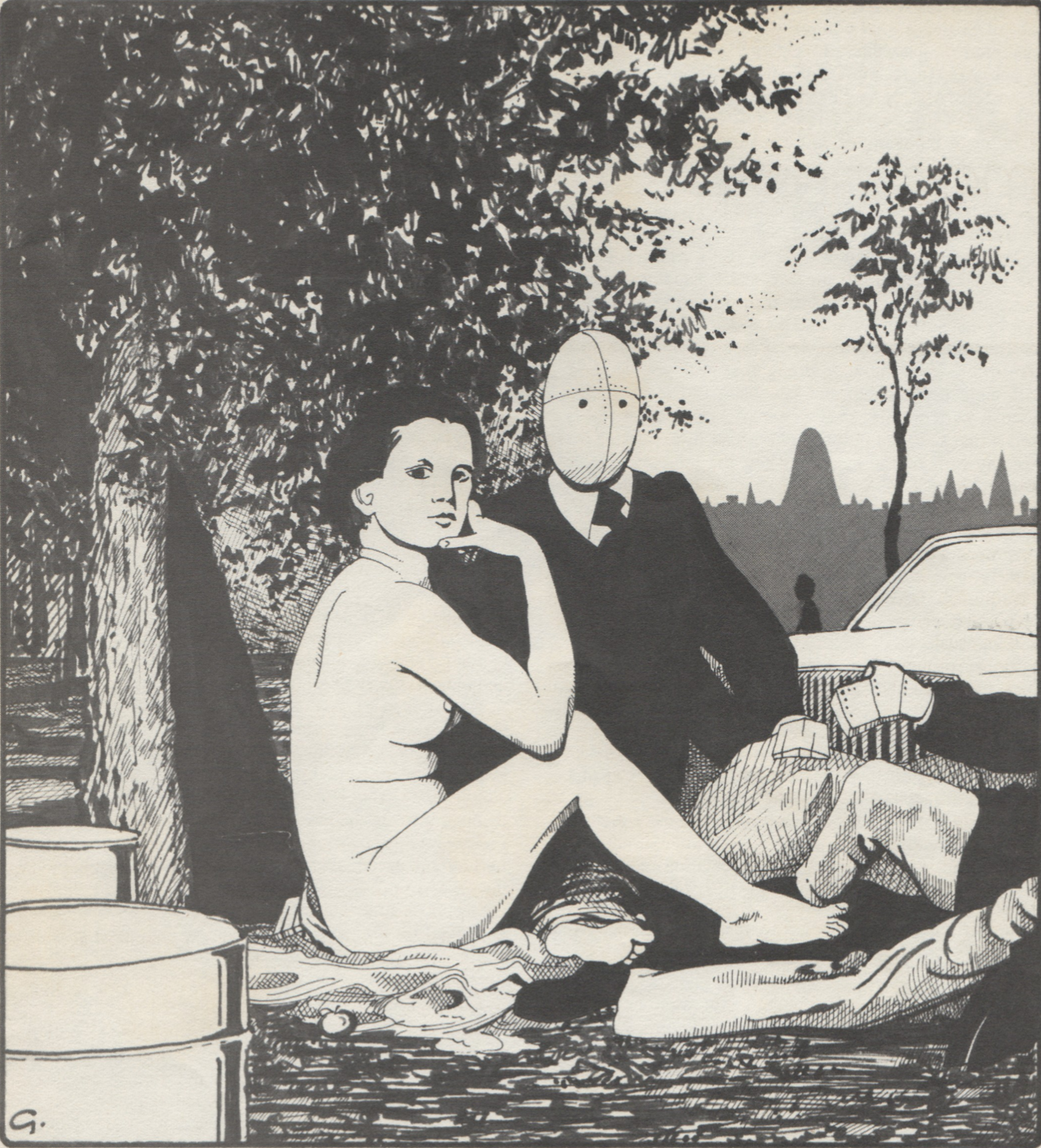

J.G. Ballard: Coitus 80: A Description of the Sexual Act in 1980

Illustration by Charles Platt.

Illustration by Charles Platt.

Familiar Ballard stuff this: a brief description of a sexual encounter interspersed with clinical descriptions of plastic surgery related to the genitals and breasts, in order to convey a sense of scientific alienation behind a simple, familiar act. I confess I hadn’t thought what goes into a vaginoplasty or phalloplasty before. It at least takes place in 1980. Three stars.

Brian W. Aldiss: The Secret of Holman-Hunt

A mock essay about an incredible breakthrough taking place in 1980 (yes!). The narrator discovers a way of unlocking the potential of the mind using the art of pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman-Hunt. No more implausible than The Stars My Destination, I suppose, but it failed to hold my attention. Two stars.

John T. Sladek: 198-, a Tale of ‘Tomorrow’

Illustration by Pam Zoline.

Illustration by Pam Zoline.

Sladek gives us a plausibly dystopian 1980s where computers can call each other up from anywhere in the world, where people’s fertility and happiness are controlled by drugs, and where everything is made of plastic. I find this vision of the future sadly compelling, though of course Sladek has to remind us that he’s Sladek through cutting the columns up and putting them out of order and sideways. Four stars.

M John Harrison, The Nostalgia Story

Another of these stories that are made up of disconnected snippets with the reader invited to make their own connections. One of these is entitled “Significant Moments of 1980” so I suppose it’s on theme. Two stars.

Joyce Churchill: Big Brother is Twenty-One

Illustration by James Cawthorn.

Illustration by James Cawthorn.

A short essay on Nineteen Eighty-Four, concluding that Huxley was closer to the mark than Orwell: the coming dystopia will most likely be a capitalist one in which we convince ourselves we are happy through the acquisition of material goods, rather than a socialist one based on a war footing. Not exactly looking forward to 1980, but at this point I’ll stretch the definition. Four stars.

Jack Trevor Story: The Wind in the Snottygobble Tree part 3

Photo by Roy Cornwall.

Photo by Roy Cornwall.

This isn’t getting any better as it goes on, though Story is making it clearer what the situation is with his protagonist (he’s not actually a secret agent, just pretending he is, however, in doing so, he’s wound up being mistaken for a genuine one). Nothing to do with 1980. One star.

Book Reviews: M John Harrison and John Clute (rendered as “John Cute” in the table of contents)

The usual suspects review the usual volumes. Nothing to do with 1980.

Obituary for James Colvin

Spoof obituary for a pseudonym of Barrington J. Bayley and Michael Moorcock. Nothing to do with 1980.

Out of 17 items, eight actually have something to do with the 1980s, broadly defined, and only five have anything to do with 1980 specifically. Nonetheless, this does feel like a more SF-related and livelier New Worlds than we’ve had in a while. Perhaps the new decade will give them a new lease on life? We can only hope!

[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!]