By Mx Kris Vyas-Myall

The news to start this decade seems to be unrelentingly gloomy. The crisis in Biafra is only worsening, Mainland China and the USSR are at each other’s throats, and, at home, the government appears paralyzed on how to deal with inflation or the Unions.

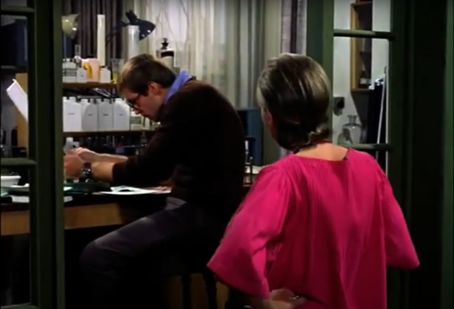

But I want to take a break from grim reality and talk briefly about one of my favourite new TV programmes of recent months, Strange Report.

It stars the unlikely team of Anthony Quayle (regular star of war films) as retired police detective Adam Strange; Kaz Garas (relative newcomer) as student and jack-of-all-trades Hamlyn Gynt; and Anneke Wills (Polly from Doctor Who) as model and artist Evelyn McClean.

Together the trio solve unusual crimes together. These have included such cases as a kidnapped Chinese diplomat, murders by witchcraft and the killing of a student demonstrator behind the Iron Curtain.

There are several reasons this appeals to me, and would to other SF fans I imagine. Firstly, even though it never becomes SFnal, the cases work from a viewpoint that feels very scientific. That no matter how odd things may seem, they will always have a rational explanation.

Secondly, the cases are willing to address complicated issues, without attempting to preach. Even in dealing with some clearly despicable characters, there is an attempt made to understand their point of view and give both sides of the argument. To me it feels like the writers have their own ideas but don’t want to patronise the viewer, we are encouraged to make up our own minds.

Finally, is the dynamic between our triumvirate of heroes. Much like in Star Trek, you get the sense that, in spite of their different viewpoints they all clearly care for and respect each other. It would have been easy to have Strange constantly belittling Evelyn and her trying to show that women could do things for themselves. But, instead, there is a respect and a willingness to listen. Perhaps that is what the terrible world outside our windows really needs?

Back in the pages of SF publications, we have our own strange reports. One coming in from Vision of Tomorrow and the other from New Writings:

Vision of Tomorrow #5

Cover by Gerard Alfo Quinn

The only point of interest in the introduction is it labelling itself as Britain’s only original SF magazine. I guess it is a point of debate if New Worlds still counts as science fiction or not.

Dinner of Herbs by Douglas R. Mason

Illustration by Jeeves

Fenella, a thought chandler at a dianetics lab, has gone to a villa to have a tryst with engineer Gordon Reid. Also staying with them is their domestic servant, a former psychologist android. But is three a crowd?

A darker and more complex tale than it first appeared. However, I think it would benefit from toning down the descriptive prose and upping the character work.

Three Stars

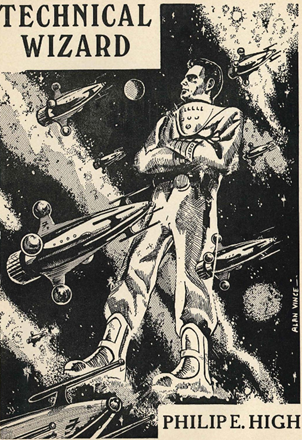

Technical Wizard by Philip E. High

Illustration by Alan Vince

Two empires in space have come into contact, the more technically advanced human empire and another larger one, populated by fox-like creatures. A single human is sent into the fox people’s empire on a broken-down old ship to warn them. A parapsychic plague has spread through the human empire almost destroying society. Gelthru and Feen have to determine if the human is telling the truth, or if it is all a magic trick to keep them from invading.

An interesting concept and I enjoyed how it made the human the other and the fox-people the protagonists. However, I feel like it needed some more editing to rise above the pack.

Three Stars

Flanagan's Law by Dan Morgan

Illustration by Jeeves

Capt. Terence Hartigan of the freighter Ladybug is finally given clearance to leave Calpryn, a planet where the main occupation, and entertainment, is lawsuits. However, five hours before blast-off O’Mara goes missing. Hartigan sets off to find him before they find themselves in more legal hot water, but the captain quickly becomes entangled in the planet’s labyrinthine bureaucracy.

I have previously failed to find Morgan’s satires either poignant or funny. This continues that trend but with the addition of some questionable Irish stereotyping.

One Star

Fantasy Review

Uncredited illustration

Kathryn Buckley reviews New Writings in SF-15, which she liked but not as much as I did, and John Foyster gives praise to The Black Flame by Stanley G. Weinbaum, Outlaws of the Moon by Edmond Hamilton, Kavin’s World by David Mason and Needle by Hal Clement.

One of the Family by Sydney J. Bounds

Illustration by Alan Vince

Having completed the terraforming of Phoebe-Four, Richard Daniels takes his wife Jane and son Kenny to the neighboring Phoebe-Five for a holiday. Whilst it is meant to be uninhabited they find an intelligent alien, who they call Alan. He quickly becomes like one of the family, but Dick finds his presence both annoying and a cause for concern.

A bit of an old-fashioned tale, but well-told and with a reasonable twist. Wouldn’t have looked out of place as an episode of The Outer Limits.

Three Stars

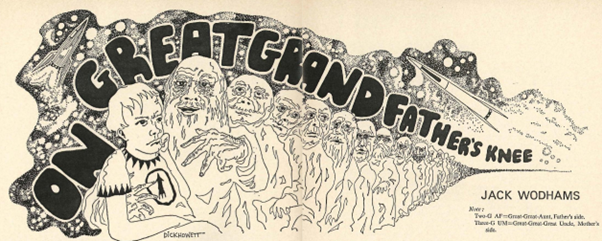

On Greatgrandfather's Knee by Jack Wodhams

Illustration by Dick Howett

Six-G GFM Frank (that is Great, Great, Great, Great, Great, Great Grandfather on your mother’s side) tells Furn tales of early space travel. But with longevity meaning all the kids having over a hundred great relatives, these tales of adventure are a dull chore.

Whilst Wodhams captures well the boredom of kids having to visit older relatives, I am not sure what the point of it all is.

Two Stars

The Impatient Dreamers: Hands Across the Sea by Walter Gillings

Insignia of Gernsbeck’s Science Fiction League, designed by Frank R. Paul

This month Gillings discusses Gernsbeck’s Science Fiction League’s branches in England, the early days of New Worlds, fanzine Scientifiction and Gillings' talks with publishers to get a new British SF magazine off the ground.

I continue to adore this series.

Five Stars

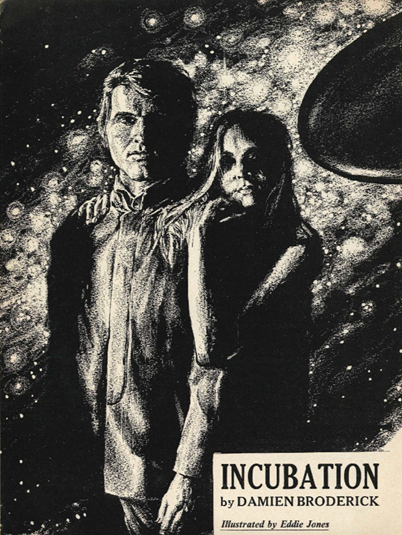

Incubation by Damien Broderick

Illustration by Eddie Jones

Clive Soame notices a strange ad in the personals and concocts a scheme to sleep with a rich woman and take her money. However, the assignation Rogel and Silver were communicating about was much more complicated than he first thought.

Whilst not revolutionary, an interesting enough take on the lecherous man and alien conspiracy genre. Surprisingly, more than the science-fictional elements, I found myself enjoying the descriptions of Sydney. Very well painted.

Three Stars

Life of the Party by William F. Temple

Illustration by Eddie Jones

In San Remo, business magnate Mannheim and reporter Don both notice a jet disappear in mid-air. Following its route, they find themselves on a strange coastline, with a giant white cube standing alone by a desert. Entering the cube, they discover a translucent liquid wall leading to a kind of theatre-cum-hotel. The missing jet passengers are there but aged and confused. Don and Manny assume it will be simple to escape, but some force is determined to keep the visitors from leaving.

Taking up over a quarter of the magazine, this is easily the longest piece here, but it makes good use of its length, creating an eerie sense of the uncanny. However, the story is a pretty old one (at times I was recalling The Odyssey) and I was disappointed with the way the women characters were written.

Evens out at Three Stars

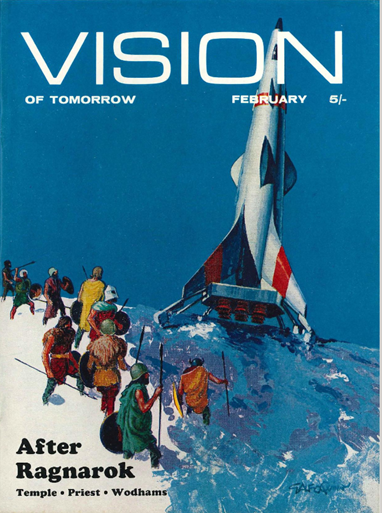

After Ragnarok by Robert Bowden

Illustrated by Gerard Alfo Quinn

The final piece is from an author who I believe is new (at the very least I have not seen him covered by my GJ comrades). After Ragnarok, the world lays shattered. Ottar and Ragnar sail the seas in their ship powered by the ancient technology of the diesel engine. There is a rumour that long ago, some of the gods escaped across the Bifrost, also called Orbit. But could it be possible they are returning? And what will that mean for the world?

Yes, it is another piece of post-apocalyptic-medieval-futurism (try saying that after a few drinks!) However, it has a good style and I have a soft spot for this type of story. The level of cynicism involved also makes it appeal to me.

Four Stars

Tomorrow’s Disasters by Christopher Priest

Instead of our usual preview of next issue’s contents, Priest gives us a short review of Three For Tomorrow. Needless to say, he adores it.

So that is it for the relative newcomer to the scene, but what about the old hand?

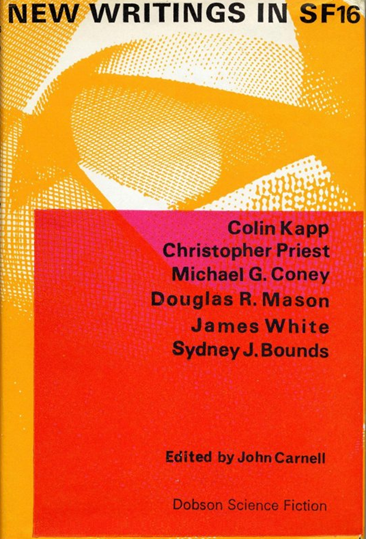

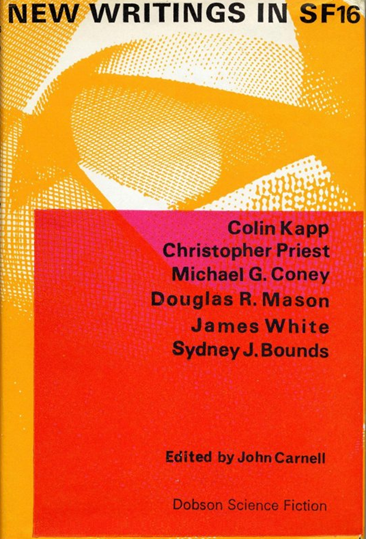

New Writings in SF-16, ed. by John Carnell

Even if we accept the contention that Vision of Tomorrow is the only British SF magazine, New Writings still helps keep up the national side with its regular doses of Carnellian science fiction. According to John Carnell, all the stories in this issue deal with problems that are galactic in scope. Let us see if that makes them Galactic Star worthy.

Getaway from Getawehi by Colin Kapp

Things don't get off to a great start with the return of Colin Kapp's Unorthodox Engineers. Here they are hired to help rescue a construction crew from Getawehi, a planet with an impossible orbit, where gravity is not perpendicular to the surface and 1+1=1.5079.

At almost fifty pages, reading through this was a major slog. These tales must have their fans, but I was personally glad when they disappeared from New Writings a few years back. According to our more learned editor, the concept is very, very, broadly viable, which raises it just above rock bottom for me.

A very low Two Stars

All Done by Mirrors by Douglas R. Mason

George Exton has developed a method of producing mirror images of himself, able to independently work on multiple tasks with the same degree of knowledge and skill as the original. But what is the cost to someone of doing this?

A well-worn trail is being beaten here, and not particularly effectively either.

Two Stars

Throwback by Sydney J. Bounds

Since the Great Change all humans have had the ability to connect via ESP. All that is, except for one person who is completely opaque to all psychic phenomena. Out of pity he is made the keeper of the Museum of Language, with access to all the books and knowledge of the world. Even though he gives weekly lectures, few care about anything other than the present. But when strange lights appear in the sky, only he can save the planet from total panic.

A tightly-told little tale. A bit obvious but enjoyable nonetheless.

Three Stars

The Perihelion Man by Christopher Priest

Capt. Farrell is grounded after an accident near Venus dulls his senses. Whilst pondering what to do with his life now, he is offered a unique opportunity to go back into space. 250 old nuclear satellites have been stolen and are now orbiting the sun, and Farrell may be the only person who can get them back.

This is Priest’s most impressive work to date. He has managed to skillfully produce an exciting adventure story that also has some interesting political elements. That is not to say it is as deep as a New Worlds piece, but it is a fun ride.

Four Stars

R26/5/PSY and I by Michael G. Coney

Hugo Johnson is an agoraphobe who has not left his apartment in two months and is believed to be at risk of killing himself. As such his psychoanalyst provides him with a roommate, robot R/26/5/PSY, or Bob for short. However, Bob is not designed to make Johnson’s life easier, not at all….

An interesting little psychological short. It felt like a combination of I, Robot, a Zola story, and The Odd Couple.

Four Stars

Meatball by James White

And we finish off with the return of White's Sector General and, as the name suggests, their continued explorations of the planet Drambo, nicknamed "Meatball". With the Drambons brought to the hospital station, they must now learn to interact with the numerous other species on board. At the same time Conway has to work out how to deal with the nuclear destruction taking place on the planet below.

It is possible that my memory is cheating me, but I don’t recall other Sector General tales focusing on a single case so much before. Maybe it is planned to be a novel fix-up? This piece definitely has the feel of a staging section, it spends a lot of time recapping earlier events and ends abruptly. Still rather interesting but does not stand alone or feel complete by the end.

Three Stars

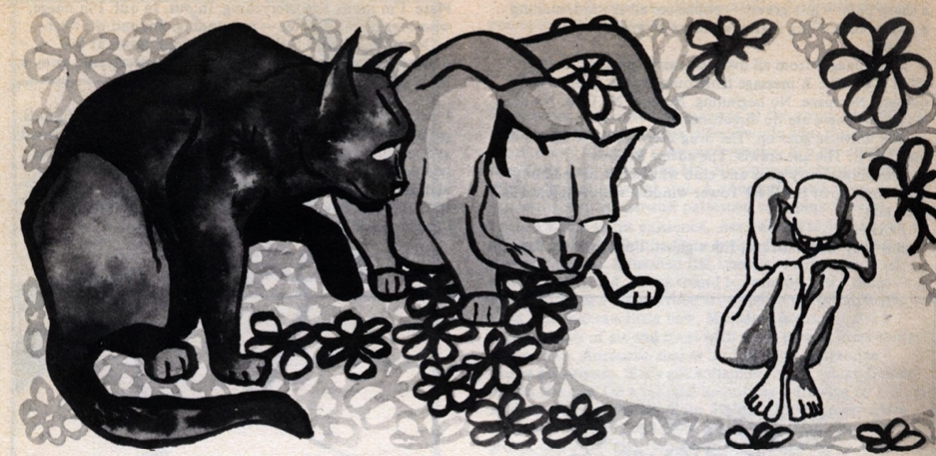

Strange Brew, Read What’s Inside Of You

Evelyn and Strange ponder what we have just read

Whether on the page or the screen, it seems that if you put a group of talented people together and ask them to deal with imaginative scenarios, they can often strike gold…or at least silver. Even if there is little here that is likely to win a Galactic Star, there is plenty worth checking out.

Here's to many more years of Vision, New Writings, and Strange Report. The seventies may not be looking much like a decade of peace and harmony, but it can at least be one of good solid entertainment.

[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!]

Follow on BlueSky

![[February 12, 1970] Up Front (March 1970 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/amz-0370-cover-672x372.png)

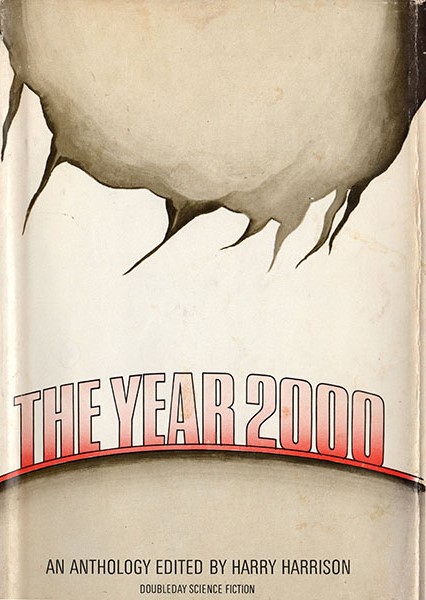

![[February 10, 1970] Thirty Years To Go (<i>The Year 2000</i>, a science fiction anthology by Harry Harrison)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/THEYEARF51970.jpg)

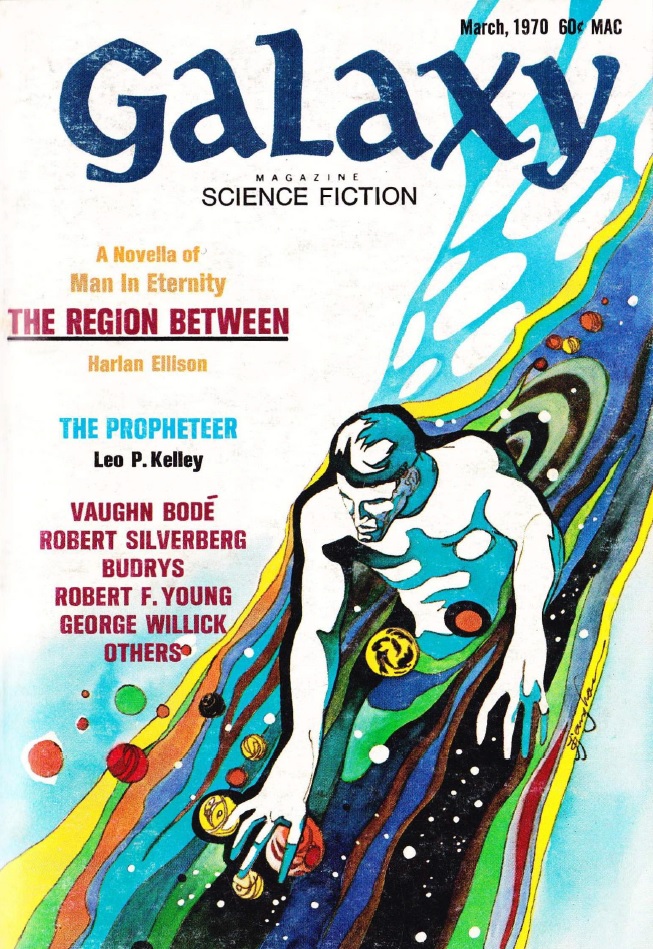

![[February 8, 1970] Boldly going to the Region Between (March 1970 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/700208galaxycover-653x372.jpg)

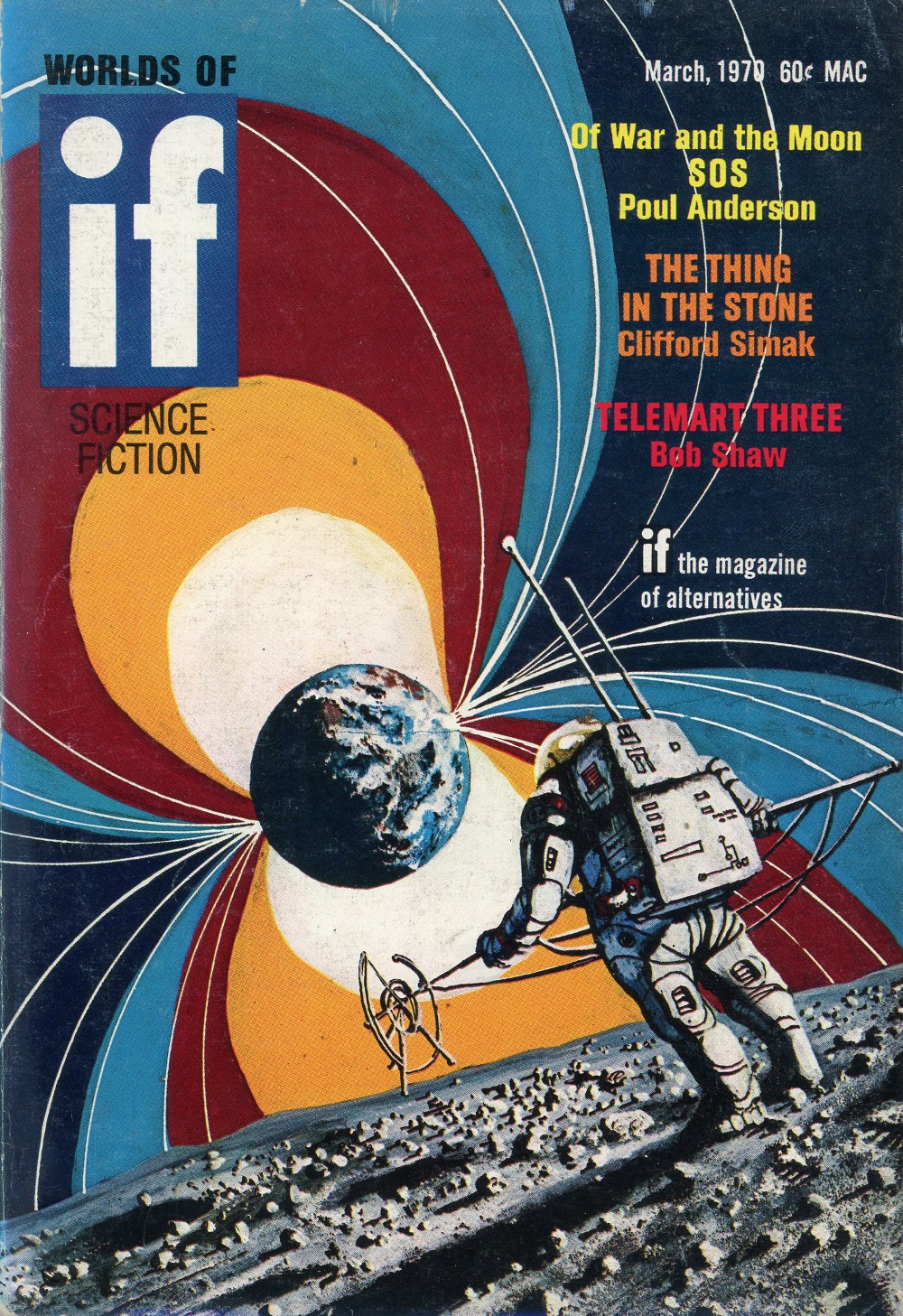

![[February 2, 1970] Deceptive Appearances (March 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/IF-1970-03-Cover-479x372.jpg)

The arbiter, an NCR 315.

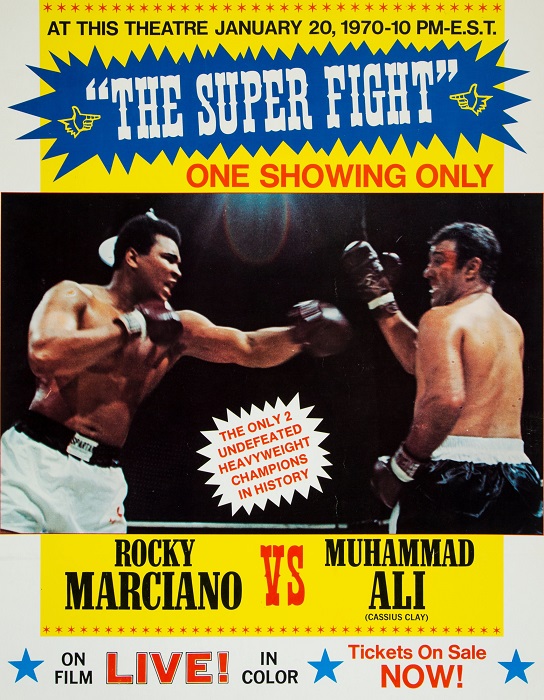

The arbiter, an NCR 315. Movie poster for the event. That “LIVE!” is a little deceptive, which is something else Ali is complaining about.

Movie poster for the event. That “LIVE!” is a little deceptive, which is something else Ali is complaining about. Art actually for “SOS,” rather than just suggested by. Maybe because it’s by Mike Gilbert, not the overworked Jack Gaughan.

Art actually for “SOS,” rather than just suggested by. Maybe because it’s by Mike Gilbert, not the overworked Jack Gaughan.![[January 31, 1970] Both sides now (February 1970 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/700131analogcover-631x372.jpg)

![[January 22, 1970] Sergeant Pepper's New Wave Writers' Club Band: New Worlds, February 1970](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/NW_2_70_cover-672x372.png)

Cover by Roy Cornwall

Cover by Roy Cornwall

Illustration, artist uncredited (possibly Charles Platt)

Illustration, artist uncredited (possibly Charles Platt)

Illustration by Alan Stephanson

Illustration by Alan Stephanson Illustration by John Bayley

Illustration by John Bayley Illustration by Ivor Latto

Illustration by Ivor Latto Illustration by Roy Cornwall

Illustration by Roy Cornwall

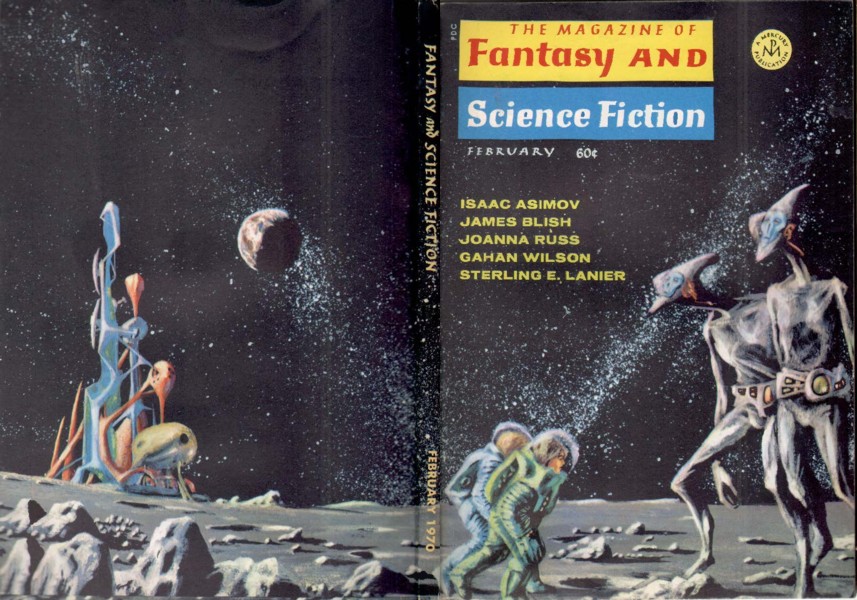

![[January 20, 1970] Jolly good Ffelowes (February 1970 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/700120fsfcover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 16, 1970] Strange Reports (<i>Vision of Tomorrow #5</i> and <i>New Writings SF-16</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/V5-NW16-672x372.png)

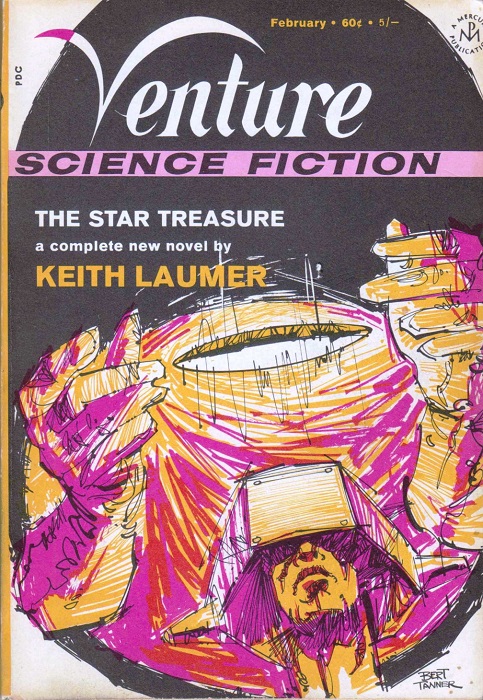

![[January 14, 1970] Root Rot (February 1970 <i>Venture</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Venture-1970-02-Cover-483x372.jpg)

A not very representational image for Laumer’s new story. Art by Bert Tanner

A not very representational image for Laumer’s new story. Art by Bert Tanner![[January 10, 1970] Time On My Hands (February 1970 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/COVER-672x372.jpg)