by Mark Yon

Scenes from England

Hello again!

June… Summer already! Well, almost. A British Summer can usually be relied upon for its inclemency. So, of course, it’s grey and dull here.

Well, at least I have the latest New Worlds and Impulse to cheer me up. Mind you, the two issues last month were rather damp squibs, if I’m honest. I am hoping that this month’s are better, although there are worrying signs here. More later.

To Impulse first.

And having rather fuzzy covers lately, courtesy of Associate Editor Mr. Keith Roberts, we have another one this month. Though it is not credited, it is clearly a Keith Roberts painting. At least I can tell that it’s a science fiction-y one.

The Editorial this month is interesting in that it is a “Guest Editorial” from Harry Harrison. After Kyril’s recent ruminating that he doesn’t know what to write about as an Editor, perhaps this is a sign that he’s given up, at least for a while.

It also rather makes me wonder how much of the work behind the scenes is actually done by the editor and how much by his Associate Editor!

Anyway, the Editorial by Harrison is OK. It looks ahead to 1968 for new sf books, and whilst there will be a number of “old hat” reissues and “rehashes of old themes”, Harry suggests that there will be new themes, probably more adult, and based on the softer sciences. It’s really a summary of the ideas that have been proposed before, both here in Impulse and in New Worlds.

Let’s move on to this month’s actual stories.

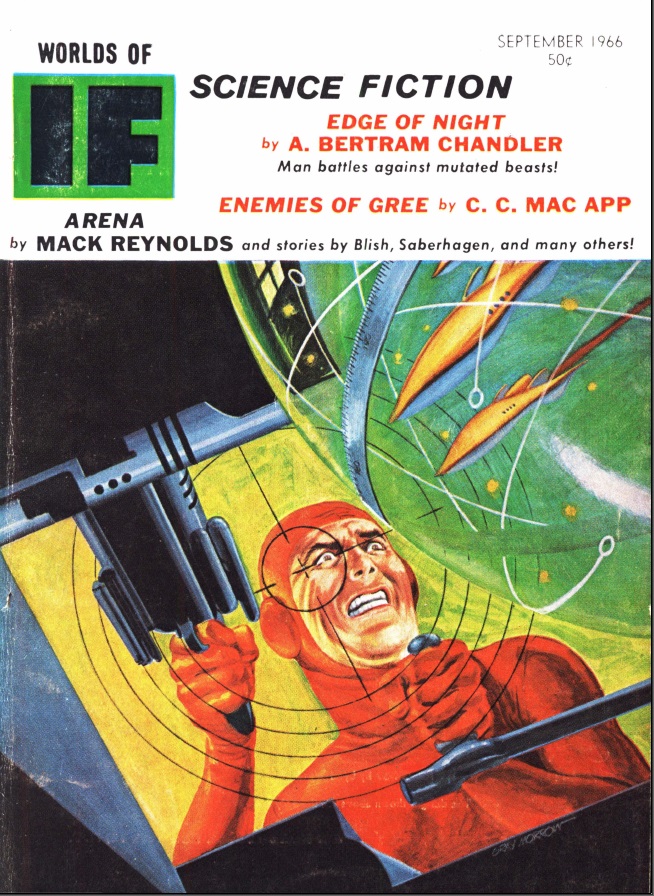

Hatchetman, by Mack Reynolds

You know Mack pretty well in the US, I think, though he is much less well known here. Last time he appeared in the Brit magazines, in the August 1965 issue of New Worlds I wasn’t too impressed, to be honest. His work in the US magazines since seems to be fairly solid, if rarely outstanding. His stories for Analog are often based on ideas from John W Campbell, which rather confirms my opinion. Hatchetman is the sort of old-fashioned story that I expect in Analog, which rather contradicts Harrison’s comments in the Editorial.

It’s a Space Opera adventure story, based upon a United Nations style organisation but dealing with planets rather than countries. The planet of Palermo, one of the United Planets, is being run by Luigi Agrigento, a Sicilian-type gangster who keeps tight control of the planet’s inhabitants in a feudal robber-baron set-up. An assassination on Earth instigated by Agrigento leads to Section G being left to arrest or kill the assassin. There’s lots of running about as a result.

It’s an entertaining read. It felt very much like a Western or a Gangster film transposed to Outer Space, the epitome of Space Opera, I guess. The characterisation is as you’d expect, and the pacing is great, though the story, whilst entertaining enough is clearly not “cutting-edge”. 3 out of 5.

George by Chris Boyce

The story of a hen-pecked husband defending his family during an invasion of dinosaurs. Not sure what annoyed me more about this one – the deliberately condensed sentences or the cloying endearments George uses towards his wife. They are designed to be annoying, but even so it was enough to put me off the rest of the story. 2 out of 5.

The Golden Coin of Spring by John Hamilton

A spaceship arrives on Earth from somewhere else to find that humans, without realising it, make the planet an inappropriate place for invasion. A basic twist in the tail story that hinges on the fact that the invading spaceship is the size of a coin. 3 out of 5.

Pavane: Lords & Ladies, by Keith Roberts

The fourth story from Roberts’ alternate History describes the social hierarchy that exists between the aristocracy and common folk in this alternate England, and perhaps something weirder.

We begin near the bed of Jesse Strange, the man we first met driving the Lady Anne steam-tractor back in the April 1966 issue. Intriguingly, Jesse is currently undergoing an exorcism and is near death.

This would be captivating enough. However, the focus of the story is really upon Anne Strange, the young niece of Jesse who is sat near the room’s window. Whilst sat she appears to go into some sort of reverie which reveals to her memories of her younger self but also visions of the future. Most of the narrative is about how the barely teenage Anne, meets Robert, who is Lord of Purbeck and lives at Corfe Castle. He woos her, beds her and then discards her. It was unclear to me whether this is past, present or both.

This could just be a historical tale of aristocracy dominating those beneath them, but Roberts adds to this elements that are definitely odd. Jesse’s home appears to be haunted, (hence the exorcism rites) but this may be due to appearance of things from other times or dimensions. In an almost Lovecraftian twist, Anne talks of and then meets one of “the Old Ones”, who seem to have some, but not total, influence on the proceedings of humans on Earth. Anne feels that she travels backwards and forwards through time in her memories, which may be the Old One’s doing.

Much of this series is about change. It is clear that some things have changed, whilst others have not. The story ends with Jesse’s death, as we seem to pass from one age to another. The role of the aristocracy appears to be on the wane, whilst the importance of the rich merchant seems to be on the rise – more signs that things are changing in this world. It’s another engaging, if at times peculiar, addition to this ongoing story. 4 out of 5.

The Superstition by Angus McAllister

A new author with an anthropological tale. When McCormick fails to return to the expedition spaceship from the Krett village, the rest of the team go looking for why. They are told that he has been taken by the Zungribs, another alien species, of which they have a number of superstitions. When the humans themselves are captured by the Zungribs, the reason for their continued existence in captivity is revealed. A one trick story, but the ending made me laugh. 3 out of 5.

Clay by Paul Jents

The return of an author last seen in Science Fantasy magazine in February 1966. In this story we visit a school where the pupils are learning to shape their thought-patterns. A bullying incident leads the teacher to turn to physically using clay as an alternative. It is the ultimate in worldbuilding, especially when the teacher can take their worlds two million years forward in time through a time furnace to see what happened. The twist in the story is pretty much expected. 3 out of 5.

Synopsis by George Hay

And the return of another author, last seen in Science Fantasy magazine in April 1965. This one is – surprise, surprise! – quite funny. (Regular readers will know how unusual that is for me.)

It is basically written as a two-page recap of a serial story that does not exist, and starts with “NEW READERS START HERE.” In spite of an unpleasant mention of “fiancée-rape”, the story could be pretty much any science fiction story in any of the magazines from the last twenty years or so. To me it reads like a cross between Flash Gordon and EE ‘Doc’ Smith. The use of words in capital letters throughout is wryly amusing. It seems to be written with affection but also with a little jab at what passes for traditional sf. 3 out of 5.

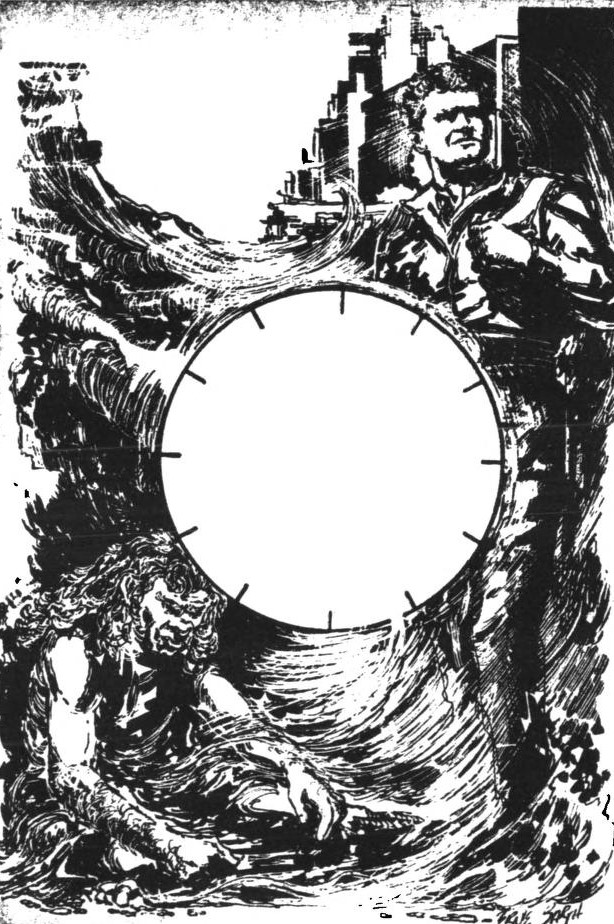

A Visitation of Ghosts by R. W. Mackelworth

The return of a regular author, last seen in Science Fantasy magazine in December 1965.

Boraston works at a school. He hates those he lives and works with and has a secret – he often draws sketches without his deliberate knowledge and he has visions that are premonitions of the future. After experiencing one vision he finds himself actually there, in a school but in some sort of post-apocalyptic future. He is given the job of helping children that are “uncontaminated” through a radiation belt to safety, which may be his reason for being there.

When he gets to the other side, he is sent back to his school to find the point in time where the apocalypse started. He changes things. The story ends with plot lines unresolved, to Boraston’s annoyance.

Despite the bad ending, I liked this one because it is a little different to the usual rockets and aliens in the magazine, although it could be straight out of a “Boys Own” adventure magazine. Something different for Mackelworth. It reminded me of H. G. Wells’ writing, which is not necessarily a bad thing – though again hardly the brave new world of Harrison’s editorial. The characterisation is rather unsophisticated. 3 out of 5.

Summing up Impulse

This issue sits firmly in the reasonable category. The Pavane story is as good as ever, the rest is readable yet fairly forgettable. His own work aside, I can’t help feeling that Roberts is filling the magazine with material from the slush pile that’s been there a while. The overall result is that of an issue that’s treading water a little, when I was rather hoping to find something that grabbed my attention more.

And with that, onto this month’s New Worlds, hoping that it is stronger.

The Second Issue At Hand

Having said already that Keith Roberts has too much to do, the cover of New Worlds is another Roberts effort!

A perfunctory Editorial from Moorcock this month. He briefly takes time to point out that there is a number of questions proposed throughout this magazine and asks for reader’s opinions, in the hope of influencing the direction of the magazine in the future, before launching into a series of quick reviews, usually left up to Moorcock’s alter-ego James Colvin.

To the stories!

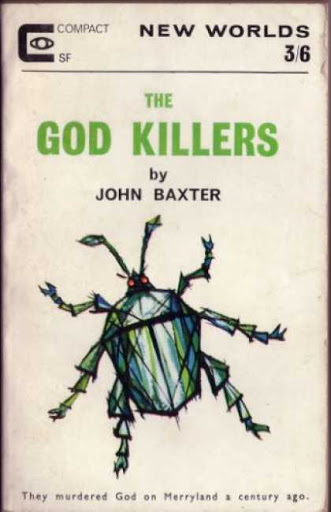

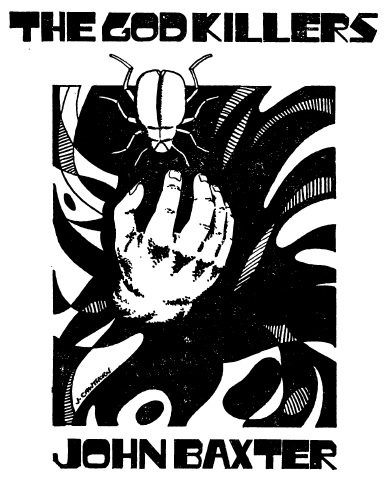

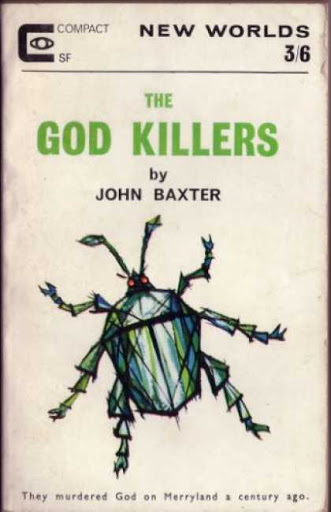

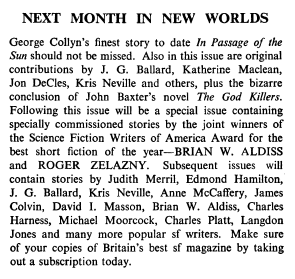

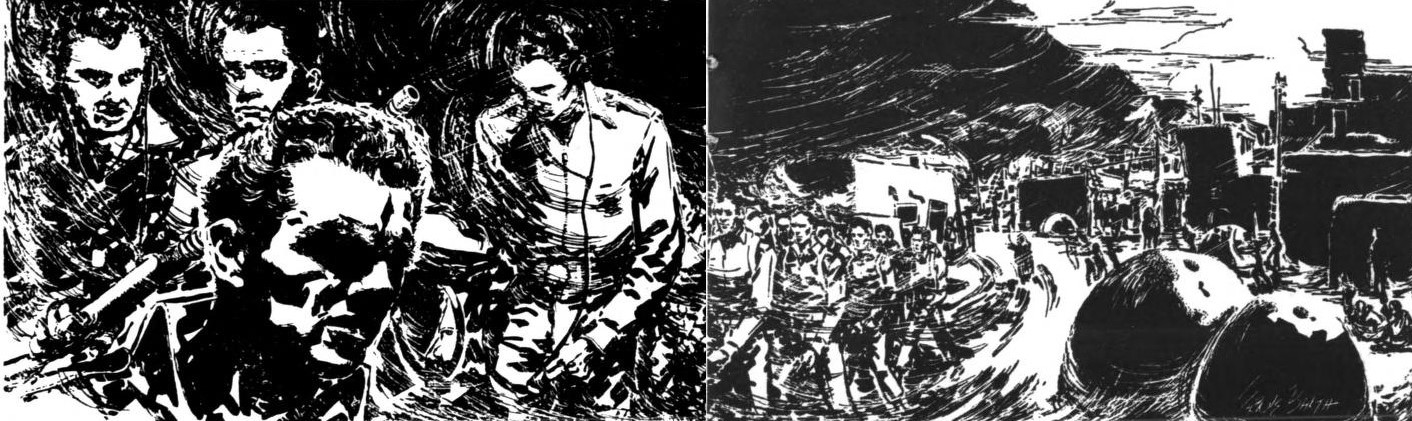

The God Killers (Part 1 of 2) by John Baxter

Here’s the welcome return of Australian John Baxter, last seen in these pages back in April with Skirmish. This time around, I must admit that I thought the title was a little too provocative, and it is. The story deserves better.

It is a narrative set mainly on the ironically-named planet of Merryland, out on the outer frontier where, after nuclear war, the residents have forsaken God and taken up an alternative religion, that of Satanism. Although focused on Satan, their ways are very Puritan to my mind – most machines are seen as abominations, reading is not something people do for fun and daily life is farm-focused. Of course, anything regarded as a sin is met with harsh punishment.

Amidst this we are introduced to young David Bonython, who is an orphan taken in by the Padgett family and who works on their farm. David is infatuated with Padgett’s daughter Samantha, but she has “gone Christian”, and he is both horrified and attracted by this fallen woman. When David is invited by Samantha to join them in one of their illicit meetings, he is enticed to go in order to spend time with Samantha.

Before this, David finds that in the farm’s attic there is a hidden matter transmitter, from which appears Earthman Hemskir. His use of a matter transmitter is forbidden, as technology of a heretic age, could lead to death or torture for David his friends and family.

We discover that Hemskir is a rogue Proctor wanted for offences against Federal law and the fact that he has stolen a carving of a beetle (like the one on the magazine’s cover this month). David realises that to get Hemskir further support he may need to enlist outside help – such as the Christians from the nearby town of New Harbour Samantha has gone to meet.

He talks to Elton Penn (great name!) who we learned earlier has spent time as an academic scholar on Earth. He is the first contact Merryland has had with Earth in hundreds of years.

The story finishes with David spending the night with Samantha at some kind of Christian ritualistic orgy. When David and Samantha return to the Padgett farm the next day they find Hemskir dead. Someone clearly knows about the forbidden technology and their involvement with it. David tells Samantha about the matter transmitter and threatens to tell her father that she’s “gone Christian” if she tells anyone else about it.

When David leaves the house to tell Penn what has happened, he finds that they have moved on. He follows their tracks for a while and finds a Satanic shrine before taking a rest and falling asleep. He decides to return to the Padgett farm, but on his return finds the farm on fire.

The title really oversells the religious aspect of the narrative. What I actually got was a well-written tale combining religious fanaticism, a teenage coming-of-age story and forbidden technology.

It’s nothing special, but it read well enough. I enjoyed it more than John Brunner’s most recent effort as a serial, and am looking forward to the second half next month. A high 3 out of 5.

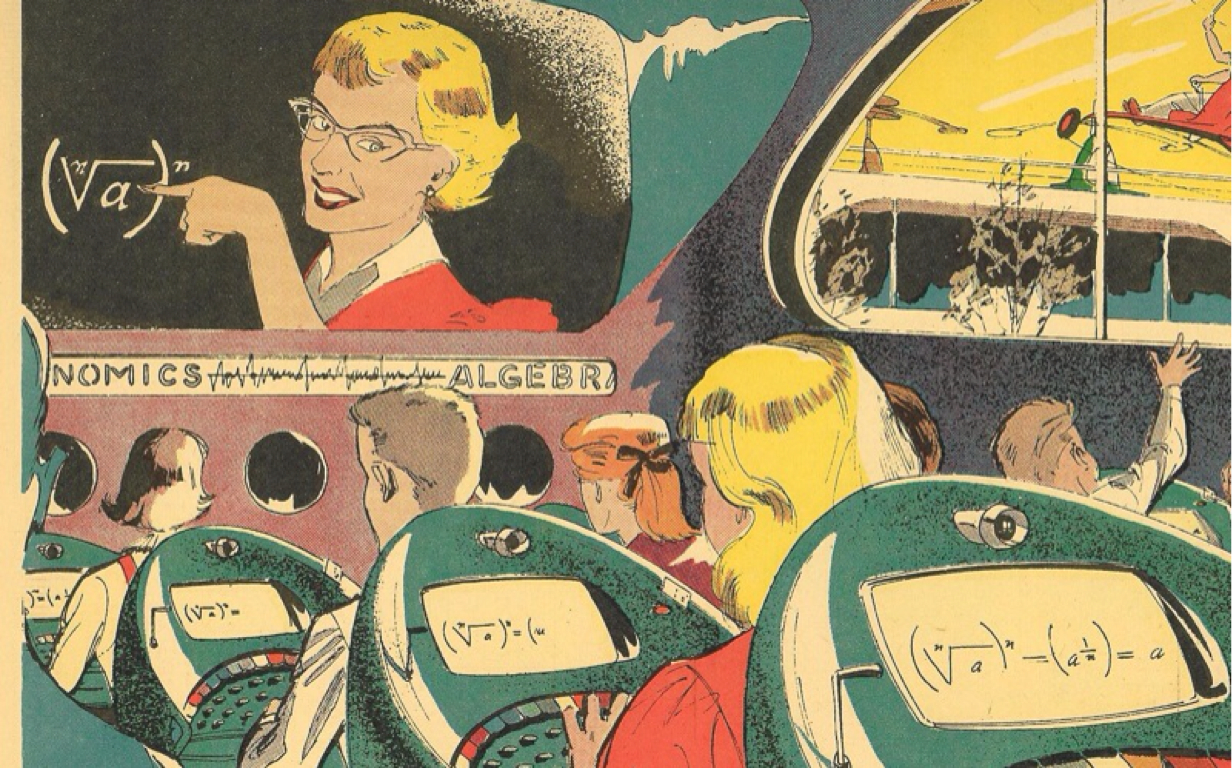

Notice how the banner text has become part of the image.

Illustration by James Cawthorn

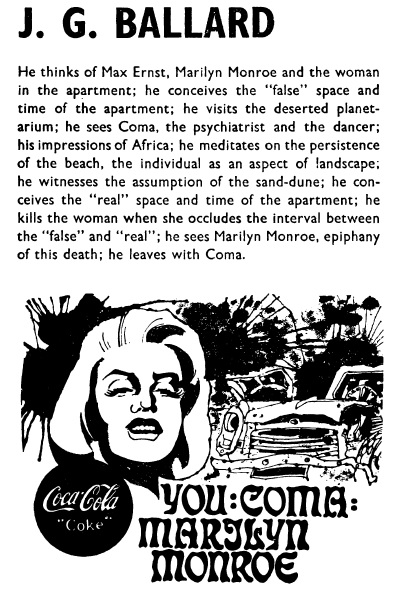

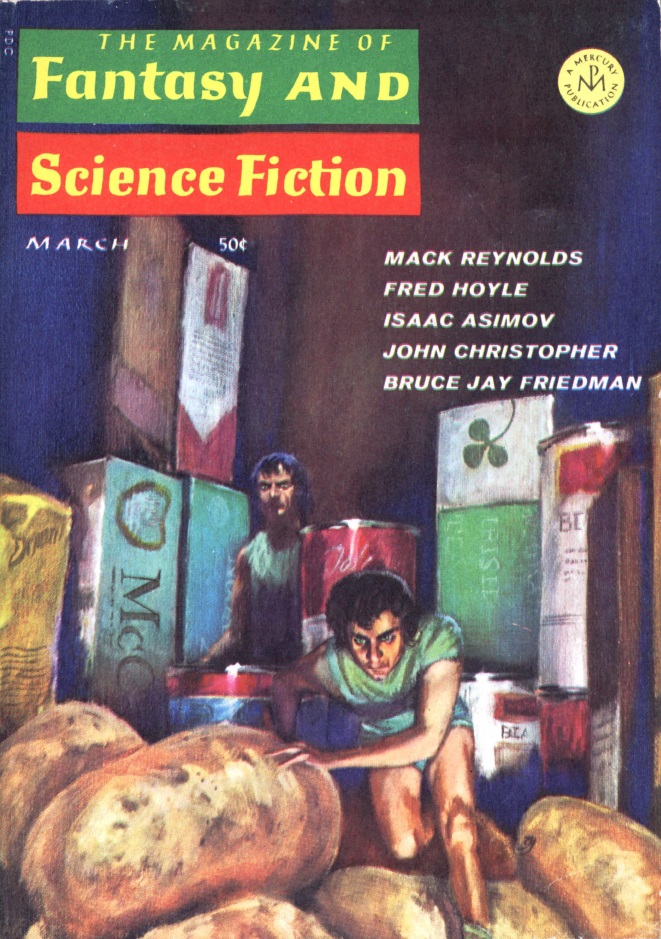

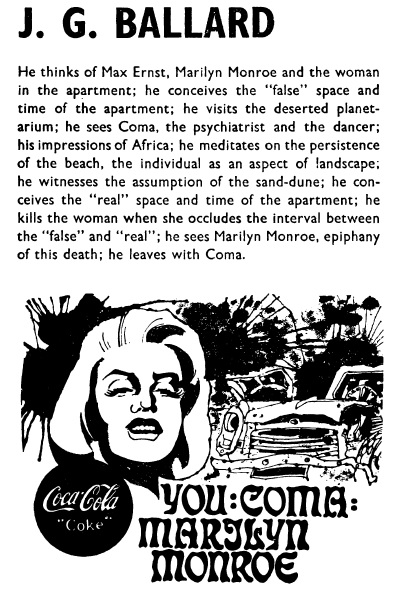

You: Coma: Marilyn Monroe, by J. G. Ballard

Here’s another one of those stories where Ballard mixes real people with his own brand of multifaceted, fractured weirdness. In April we had John F Kennedy, Malcolm X and Lee Harvey Oswald, this time we have Marilyn Monroe. Still as bizarre as before, as the writing with the artwork at the beginning of the story shows. Ballard continues to mix fact and fiction in his deliberately compressed prose, non-linear fashion.

Lots of pieces of story, admittedly well written from different perspectives, that form an incoherent whole. This still reads like a story extract, using characters such as Karen Novotny that I first read of in The Assassination Weapon, but this time Instead of Kline as the protagonist we now have Tallis.

Much of Ballard’s work is about the repetition of words and images, and it is so here. The prose seems obsessed with geometry and angles, not only those of Karen Novotny, but also of the apartment room she is in. Is this Tallis trying to make sense of the world around him? Possibly. Whatever the story is, I think I am now starting to get how the disparate pieces connect together, but it is deliberately obtuse.

Like the other story, it stays with you after you’ve read it, even if I’m still not entirely sure what it is I’m reading. A bit of a cheat though, in that the story has already been published in the Spring 1966 issue of Ambit magazine. 4 out of 5.

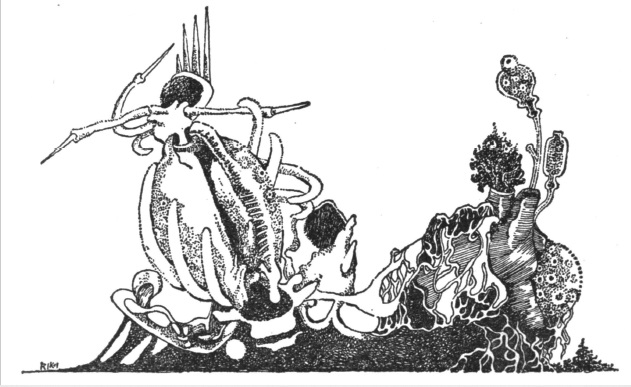

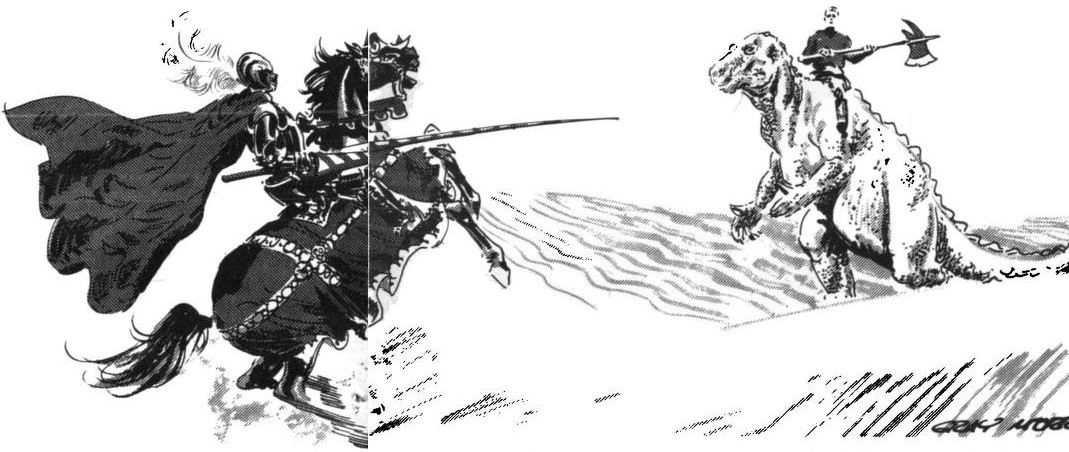

The God-like Niktar

Illustration by Yates

The Gloom Pattern, by Peter Tate

Peter’s last effort was the rather awkward romance Fifth Person Singular in last month’s issue. This story is better, though still not great. Charlie and Nicholas are two bored schoolboys who set themselves a challenge – to make single man Gregory Birtle smile. Alien Niktar, Superemedial Agent to the Sad Sometimers, sends Gregory his secret weapon, to examine “the human reaction to a state where sorrow has been banished and happiness and its attendant joys are the order and the law.” This is a girl robot named Satina. She does manage to bring a smile to Birtle's face, but the ending is a mess. 3 out of 5.

Sub-liminal, by Ernest Hill

Another of Moorcock’s regulars. Clearly meant to be ironic, Sub-liminal is about a politician of the future trying to rig the voting of an election, only to find too late that another deal has been made. The fact that the politician is named Sir Jocelyn Diddimous may say it all. 3 out of 5.

What Passing Bells?, by R. M. Bennett

In a time after a nuclear war, the survivors fight it out amongst themselves. Women are used for entertainment, men are locked away and left for stealing another’s hoard of stuff. It doesn’t end well. This one’s unremittingly bleak and generally unpleasant. Not my cup of tea, but fine for what it was. 3 out of 5.

Illustration by Douthwaite

World of Shadows, by S. J. Bounds

In which the most exciting thing is that regular writer of the space-filler, Sydney J Bounds, has now mysteriously become 'S. J. Bounds' on the Contents page.

Would-be gangster Fatso Tate lands on a new planet to start a new life away from the prying eyes of the Patrols wanting to hunt him down. Watching the twin shadows created by the planet’s two suns, he soon finds that the shadows have a life of their own. Readable, but unconvincing. 3 out of 5.

Letters and Book Reviews

A lot of reviews this month prompted by the proliferation of new material, anthologies and reprints. All the reviewers are kept busy this month. James Colvin lists many. He is dissatisfied by Samuel Delany’s work, finding his purple prose “off-putting”, disappointed by Dick, finds himself not a fan of Zenna Henderson’s “brand of sentiment”, refers to Heinlein as “science fiction’s answer to Agatha Christie” and finds the re-issue of Brian Aldiss’s The Canopy of Time as “the best of this month’s whole batch”. Lots and lots of others mentioned as well, though.

James Cawthorn takes on reviewing duties this month as well as his artistic work. He is more positive about Zenna Henderson’s work than Colvin was, and he also covers a wide range of new and old work. Like Colvin’s reviews this month, there are too many to mention individually, but the reviews are entertaining, succinct and insightful.

We have no Letters pages this month – perhaps Moorcock has gone for a lie-down after the recent furores over religion.

Summing up New Worlds

I liked Baxter’s God Killers this month, even if it tries too hard to shock. Ballard still confuses and impresses. Whilst the rest veers between the mundane and the overblown, it is a better issue than last month’s, though still not an outstanding one.

Summing up overall

Is there enough there in either issue to keep the old readers and entice others to pick up an issue? I’m not sure.

In the end, I decided that Impulse was the better of the two, although I could easily see other readers opt for New Worlds.

Until the next…

>While you're waiting, tune in to KGJ, our radio station! Nothing but the newest and best hits!

![[February 20, 1967] To Ashes (March <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/670220cover-661x372.jpg)

![[December 31, 1966] Barriers to quality (January 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661231cover-672x372.jpg)

![[November 30, 1966] Marking time (December 1966 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/661130cover-672x372.jpg)

![[November 24, 1966] Middling (December 1966 <i>Amazing</i>)</big></b>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/amz-1266-cover-503x372.png)

![[September 30, 1966] Return to Base (October 1966 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/660930cover-672x372.jpg)

![[August 2, 1966] Mirages (September 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/IF-1966-09-Cover-654x372.jpg)

![[June 30, 1966] Not Reading You (July 1966 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/660630analog-500x372.jpg)

![[May 24, 1966] Hatchetmen, Marilyn Monroe and God Killers (<i>Impulse</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, June 1966)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Impulse-New-Worlds-June-1966-672x372.jpg)

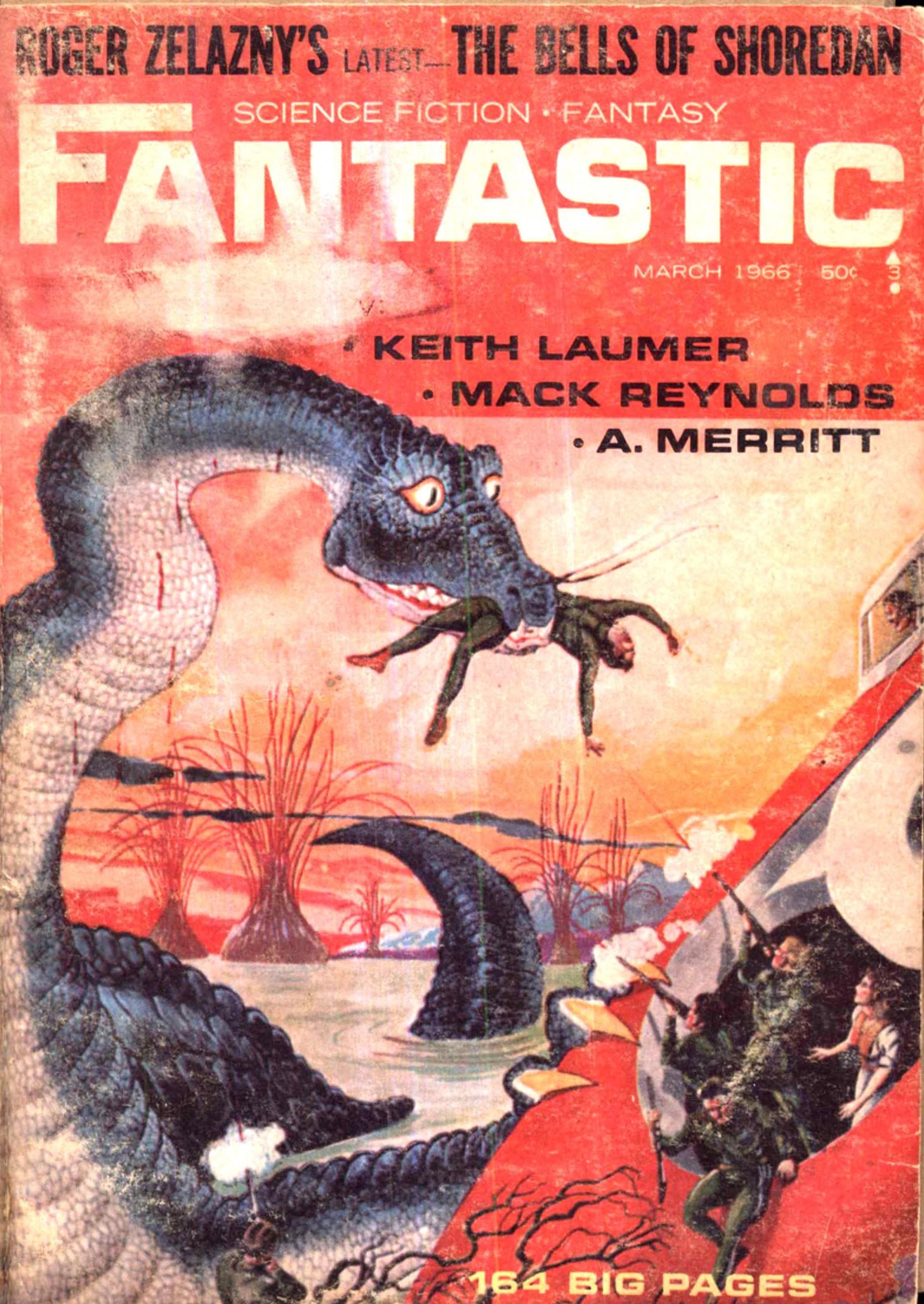

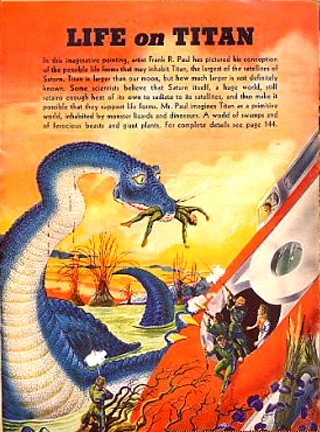

![[February 12, 1966] Past? Imperfect. Future? Tense. (March 1966 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Fantastic_v15n04_1966-03_0000-3-672x372.jpg)

![[January 31, 1966] Milk of Magnesia (February 1966 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/660131cover-672x372.jpg)