By Mx Kris Vyas-Myall

The National Radio Astronomy Observatory may have discovered clues to the origins of life in space. Looking at interstellar clouds, believed to be where planets and stars are formed, traces of formaldehyde have been detected.

140’ Radio Telescope at Green Bank, responsible for this discovery

The reason this is important is that it is a sign of the presence of methane, formaldehyde occurring in the oxidation process. From the Miller-Urey experiments, it is widely believed that for primitive life to occur, you need a reducing atmosphere to allow complex molecules to form. Along with already detected ammonia and water, these appear to show the elements needed for a reducing atmosphere are already present in these clouds.

If this is found to hold up, we may be a step closer to understanding the birth of life on Earth.

On British television, we are also seeing a kind of rebirth. Of Out of the Unknown without the driving force of Irene Shubik.

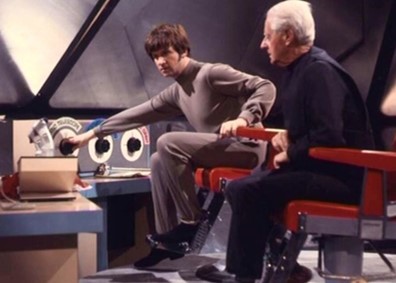

Out of the Unknown

With Shubik’s departure for The Wednesday Play, following the commissioning of scripts, it has been up to new producer Alan Bromly to make them a reality.

In many ways Bromly is the opposite of Shubik, an old hand at directing and TV production back to the early 50s, but with little experience in Science Fiction. Rather he has made a name for himself across a range of different productions, most notably the anthology slot BBC Sunday Night Theatre, soap opera Compact and films such as The Angel Who Pawned Her Harp.

So how did it turn out?

(I would like to take a brief moment to thank my colleague Fiona for using her contacts at the BBC to provide us with colour publicity photos. I am still using a Black & White set at home).

Big Prophets, Short Returns

The hunt for good science fiction begins.

This series of plays opens with a well-known novel, Robert Sheckley’s Immortality Inc. Even though this does a reasonable job of condensing the story into a 50-minute slot, and it bounces along quite nicely, I find both versions a bit soulless. I just find I am not really invested in who gets the body, which is a big problem for the central conflict.

Whilst it has some notable fans, our editor gave the original story three stars and I think that is about right for this production.

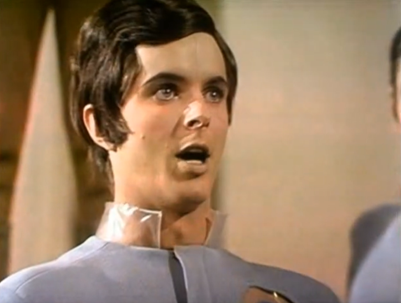

“Why, yes I do look a lot younger than Cushing did, let’s not go on about it…”

Different issues plague the other novel adaptation of the season, Asimov’s The Naked Sun.

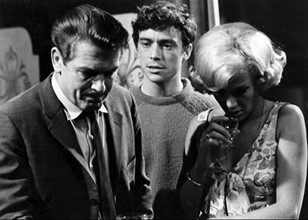

The script makes an effort to place this as a sequel to the 1964 production of The Caves of Steel, with Bailey opening the story talking about “Caves of Steel”, his delight at being partnered again with Daneel, and Secretary Minim referencing the previous case in Brooklyn. Even if Paul Maxwell (Fireball XL-5’s Steve Zodiac) is no Peter Cushing, he still does well paired-off against relative newcomer David Collings.

As people know of the original novel, the case is pretty interesting and, even if at times it feels a bit overwrought with all the yelling, the twists and turns of the story kept me engaged. The problem stems from the conversations largely being communicated through viewscreens. Unfortunately, whilst Rudolph Cartier is an experienced director (and did a great job on Level Seven), he fails to give it flair Saville did in The Machine Stops.

Herbie awakes to find himself in yet another Asimov adaptation

Of course, Shubik could never choose just one Asimov script, so our second is Liar! Robot romantic comedies seem to have become a regular feature of Out of the Unknown (see also Andover and the Android, Satisfaction Guaranteed) but this one missed the mark for me somewhat.

This has never been my favourite of Asimov’s Robot stories and the teleplay has similar issues. I find the psychic robot too contrived and I really don’t enjoy how much of it is built around Calvin’s attraction to her colleague.

It is well-made and Gifford gives a great performance as the robot psychologist (now her third on-screen depiction), so it will probably appeal more to others. But it is not entirely to my tastes.

“I am no longer just Captain Blue, I am now also Captains Lilac, Pink, Fuschia, Green and Khaki”

The third big name writer to be adapted in this run is Clifford Simak and his stories are the ones that tread into the most traditionally SFnal territory, starting with the first contact tale of Beach Head.

I will concede that it looks excellent, with the unusual design of the robots and the aliens being particularly noteworthy. However, this was the weakest installment for me, with three different problems.

Firstly, not all of the performances are pitched right, particularly Ed Bishop playing the lead role very broadly. This is more important in this story where neither the robots nor the aliens speak or emote. As such we rely on the human actors to carry the weight.

Secondly, the action in the first half is divided between robots outside and humans inside, making the pacing glacial until the aliens arrive.

Finally and most significantly, as Victoria said in her review of the original tale, this is not a particularly good example of a puzzle story and it doesn’t add up to much. So, however much it is nice to look at, you spend your time going through a lot of dull content for a rather empty ending.

Set course for planetfall…again!

The other Simak marks another first for Out of the Unknown, Shubik electing to remake a script already done for Out of this World, Target Generation.

Even those SF fans who did not catch its first use will find the tale a familiar one. It is not that it is not a good exploration of the standard themes about blind faith and static thinking leading to our doom, just not one with many surprises. Possibly one for the casual viewer not so aware of science fiction cliches.

Medical Marvels

Channeling his inner Timothy Leary to find the truth in a pill

The Yellow Pill is also a script reused from Out of This World, actually being the first episode of that series, yet I felt its restaging works better than the Simak. This is because it is somewhat more unusual in its content.

Whilst its staging could feel a bit old fashioned, largely only utilising a single set, this play-like feeling adds to the sense of unreality we are meant to experience. Add into this a strong script, great performances and the questioning of what is real, and it still feels fresh.

The most important use of futuristic medical devices, removing bags under the eyes

The Yellow Pill is only one of several scripts that concentrate on the medical aspects of technological progress. Kornbluth’s The Little Black Bag looks at what might happen if future medical equipment ends up in the past.

Even though I feel this has a solid idea at its core, the episode could have done with a bit of a reworking. It does have some great moments (particularly in the last ten minutes), however the pacing goes back and forth too much for my tastes. I also found that parts are over-explained, whilst other vital questions are left hanging.

The generation gap on show

Michael Ashe’s The Fosters (an original for OOTU) seems at first like it might be a piece of domestic drama about the conflict between respectable middle-class families and rebellious youth. But it unfolds nicely in little moments, with the titular couple’s unusual knowledge and strange eating habits bringing with it unease and tension. Even though the end reveal is a bit of a letdown, the journey is a strong one.

Pregnancy screening has come a long way from HIT

Even though the UK’s fertility rate has been steadily declining for the last few years, overpopulation is still a major topic among SF writers. Brian Hayles (of Ice Warrior fame) continues that discussion in 1+1=1.5, an original where the wife of a population control officer becomes pregnant for the second time.

The result is a bit of a mixed bag. It has interesting elements with the catchy jingles on population control, reminiscent of The Year of the Sex Olympics, and it has in its lead roles the great pairing of Bernard Horsfall and Julia Lockwood.

However, I found the mystery of how Mary got pregnant was overemphasized, resulting in a rather dull conclusion, when I would have preferred a focus on the more interesting human side.

The Human Element

“I wonder if I can get the cricket on this?”

This human element can be seen in the final of the original productions, Donald Bull’s Something in the Cellar. This is a Nigel Kneale-esque production, putting a science fictional twist on the gothic haunted house story.

I will concede it does stretch out a bit, but it is still spooky and character driven, with the voice of the “mum” being particularly unsettling.

Two Worlds, how to choose between them?

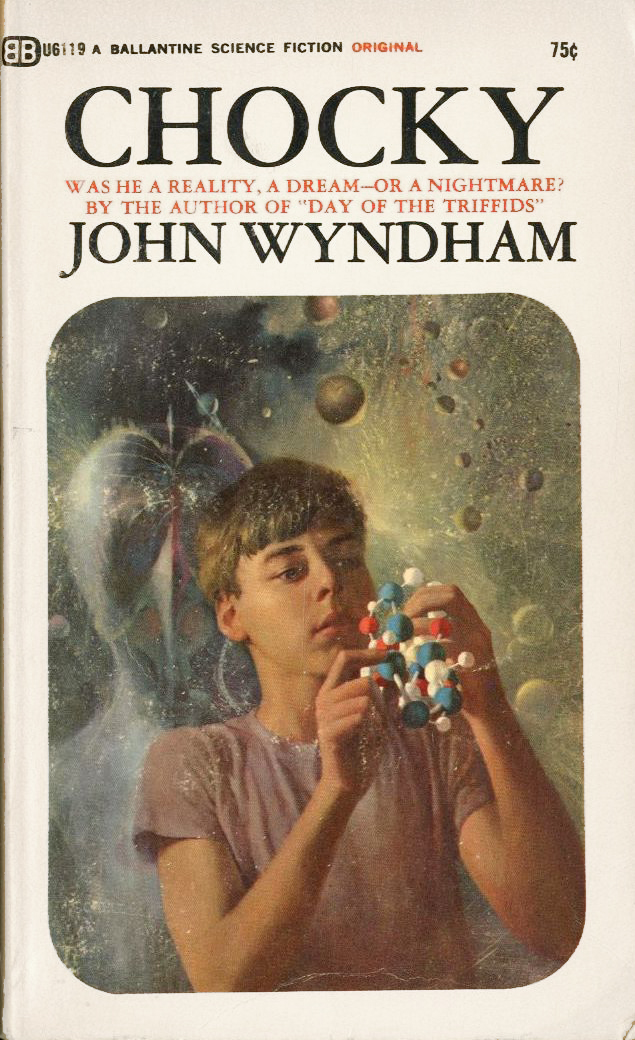

This kind of character-driven storytelling is also present in John Wyndham’s Random Quest, a story of dual time-scales.

Whilst I was never as much of a fan of this Wyndham as some of his other works, and found the script a bit drawn out, I cannot fault the production overall. The design of the parallel universe England is well realized, with the Edwardian touches being very clever. It would also be easy to find the whole conceit rather confusing, but the crew did a great job of helping the audience understand the split in the narrative.

Apparently, this has gone down extremely well and there has even been interest floated in adapting it for the big screen.

An inebriated Hale doesn’t realise the trouble coming to him

After the great production of Some Lapse of Time back in the programme’s first run, I was pleased to see another Brunner for this series with The Last Lonely Man.

Even though the original story, as Mark noted, is nothing special, this is a largely straight adaptation raised up by a number good choices:

• The casting of George Cole and Peter Halliday as Hale and Wilson respectively.

• Jeremy Paul expands the wider implications of the tale, making mentions of problems of inflation, sexuality and psychological breakdown.

• Making the death of Wilson the mid-point of the story, rather than the ending.

• Douglas Camfield’s direction making it a creepy tale of paranoia instead of a farce.

I do find it curious Shubik chose it for the same season as the conceptually similar Immortality Inc., but this one shines rather than dulls in comparison.

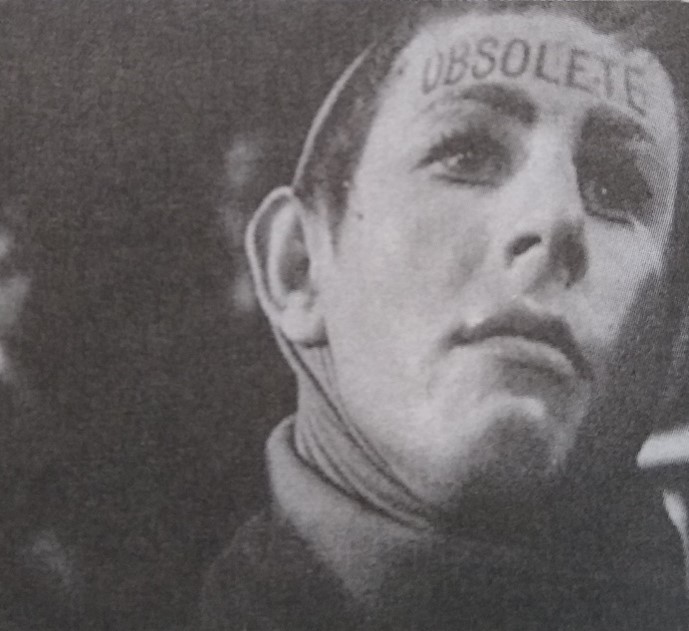

“It is all quite simple. You are actually a science fiction writer, in a dream, that is drawing from SF cliches, that is part of a teleplay on BBC2, which is adapted from a novelette, originally published in Astounding Magazine.”

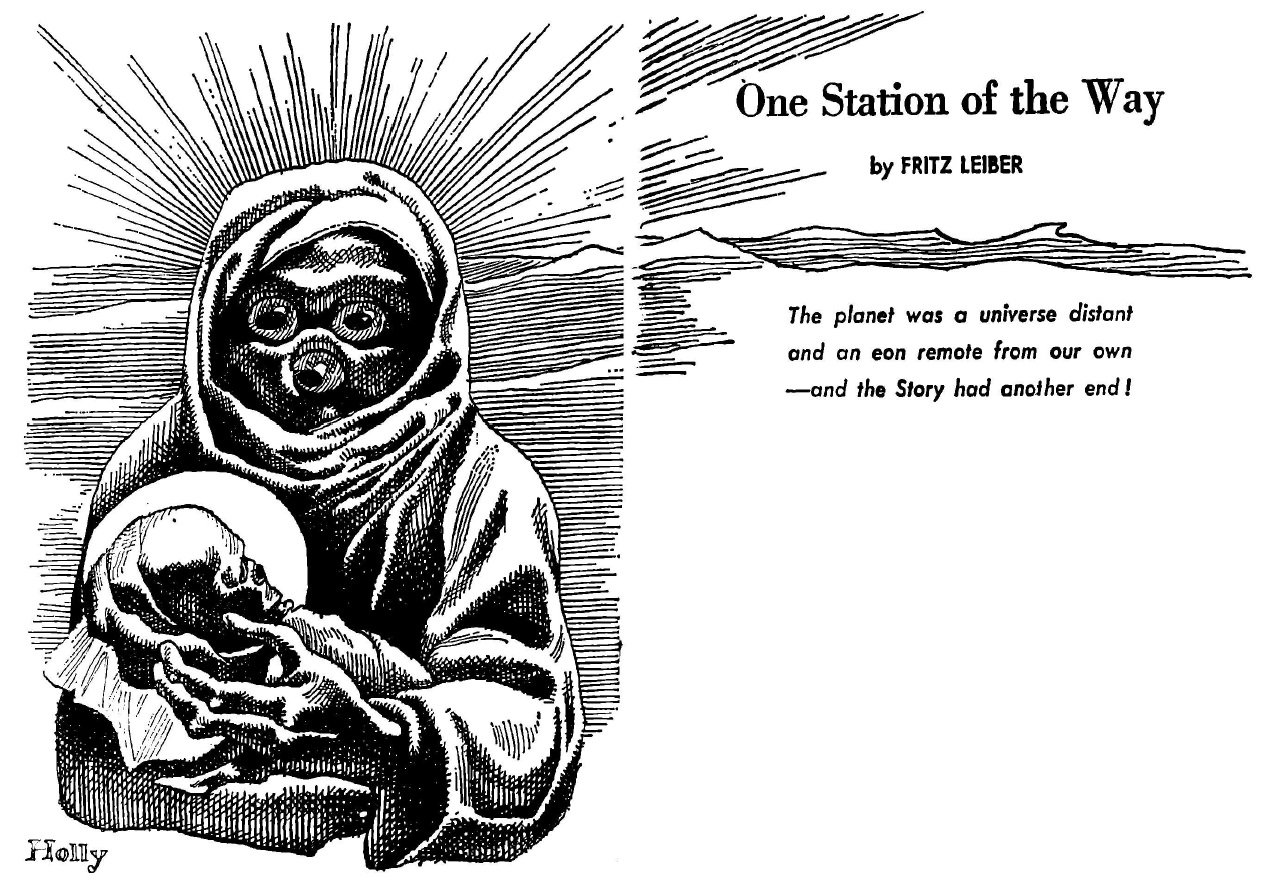

The series is finished with one of its finest ever productions, Get Off Of My Cloud.

Adapted from the excellent story Dreams are Sacred by Peter Phillips (well known to British readers due to its inclusion in the highly regarded Spectrum III anthology) it is a comical take on the cliches of pulp science fiction whilst also asking questions about the nature of fantasy versus reality.

As well as transferring the setting to the UK and adding in some wonderful Britishisms (Raymond Cusick did the design work for this episode and his incorporation of Daleks and the TARDIS are marvelous) it also builds on the idea of our childhood fears and looks at how we conquer them.

The Queen is Dead, Long Live the King

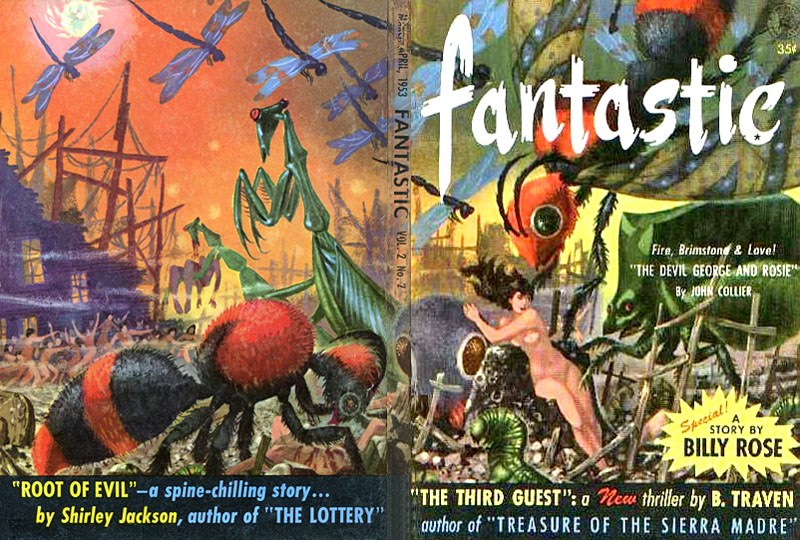

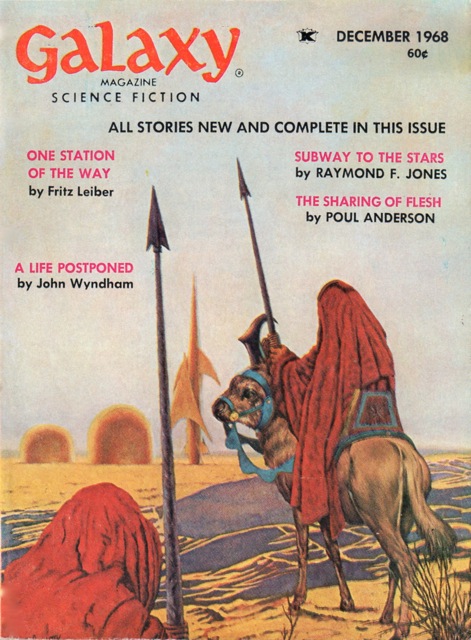

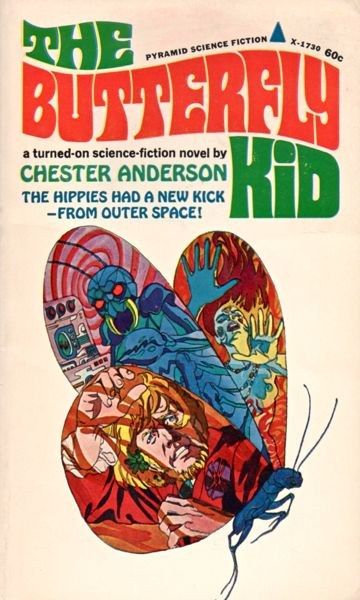

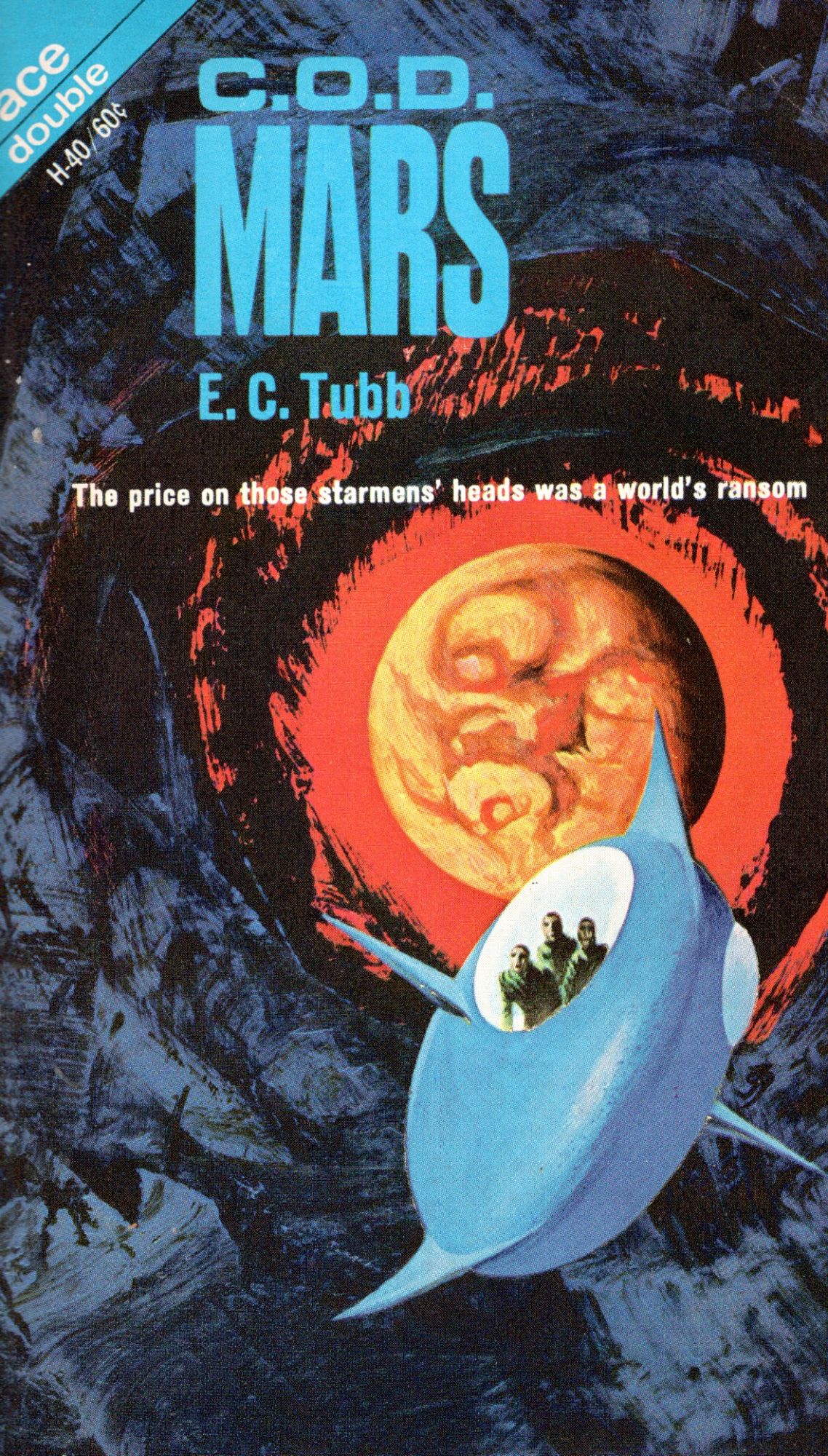

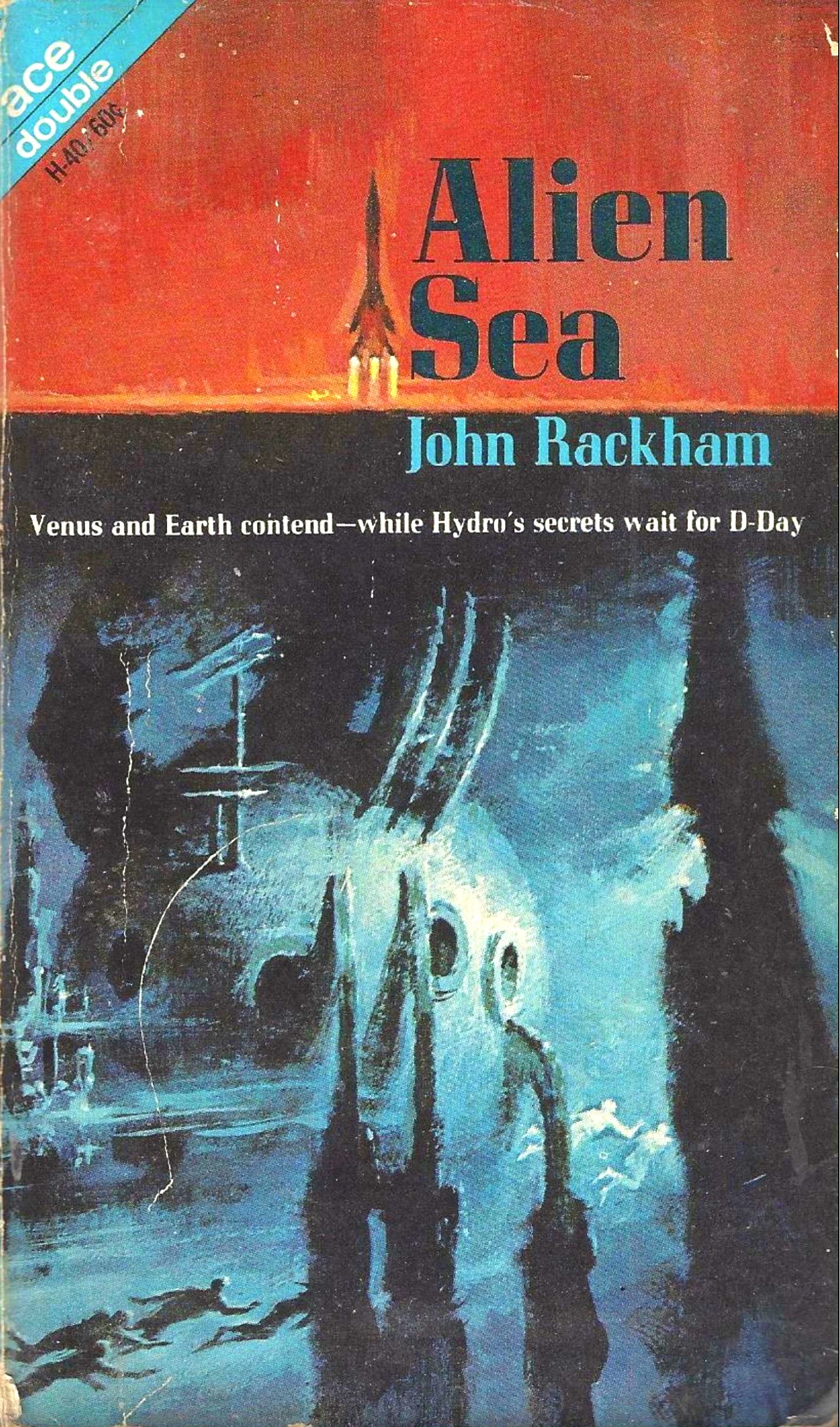

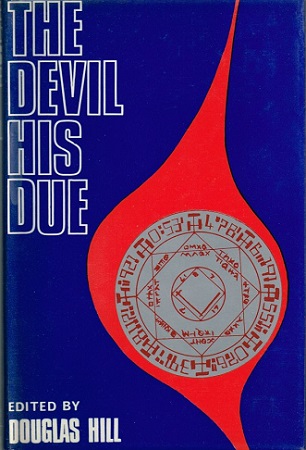

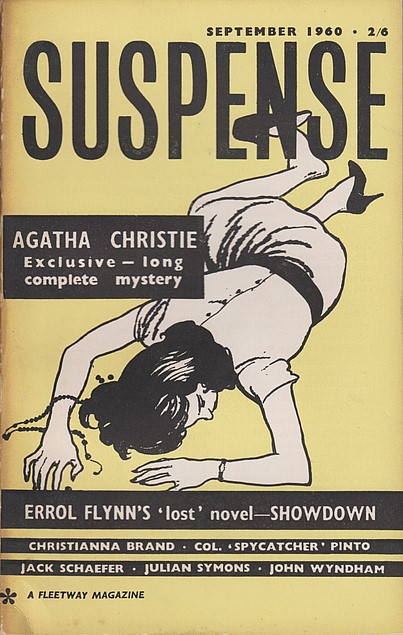

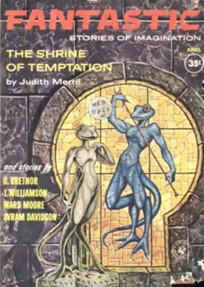

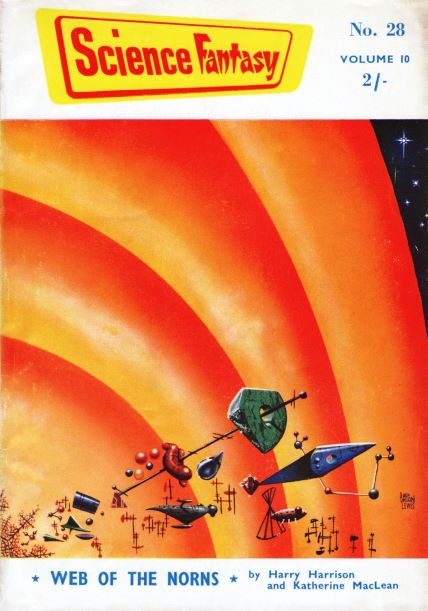

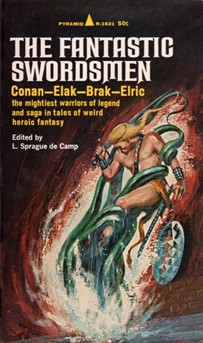

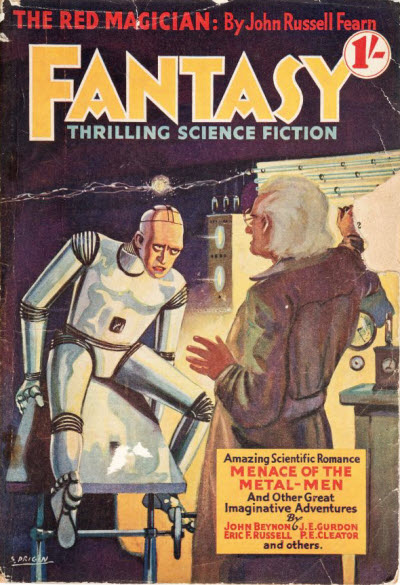

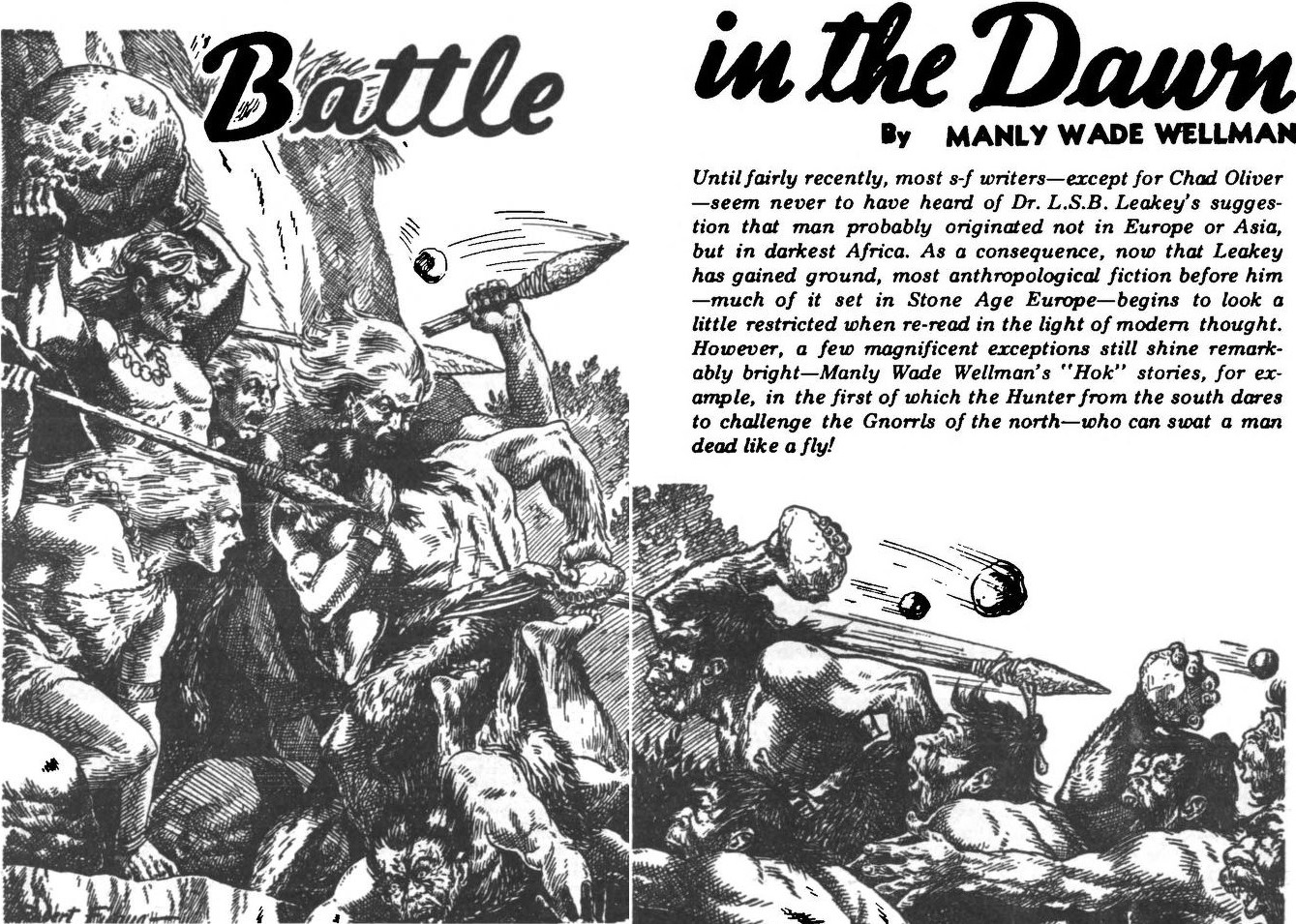

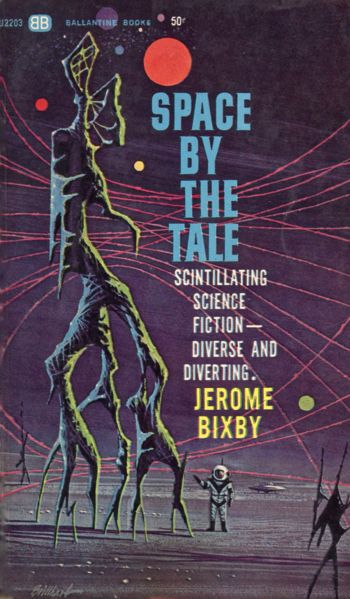

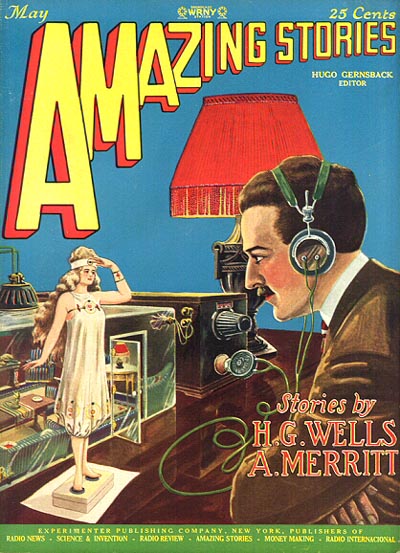

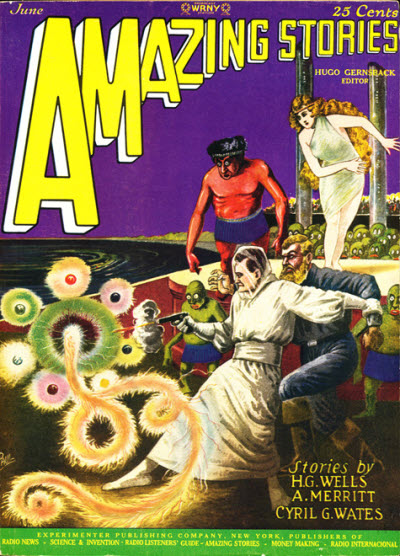

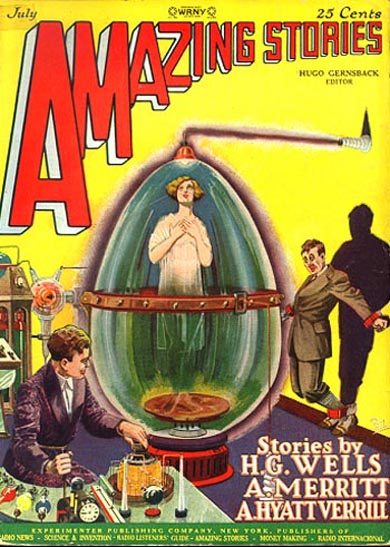

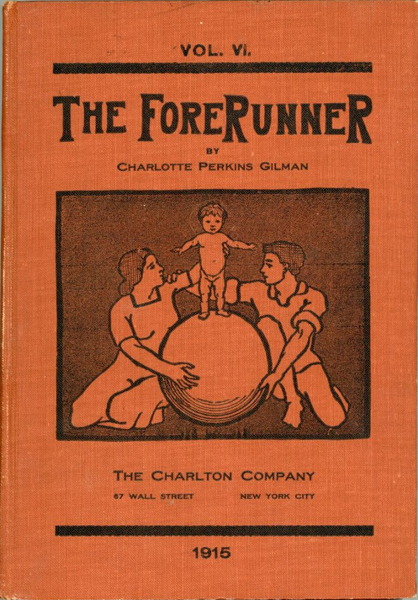

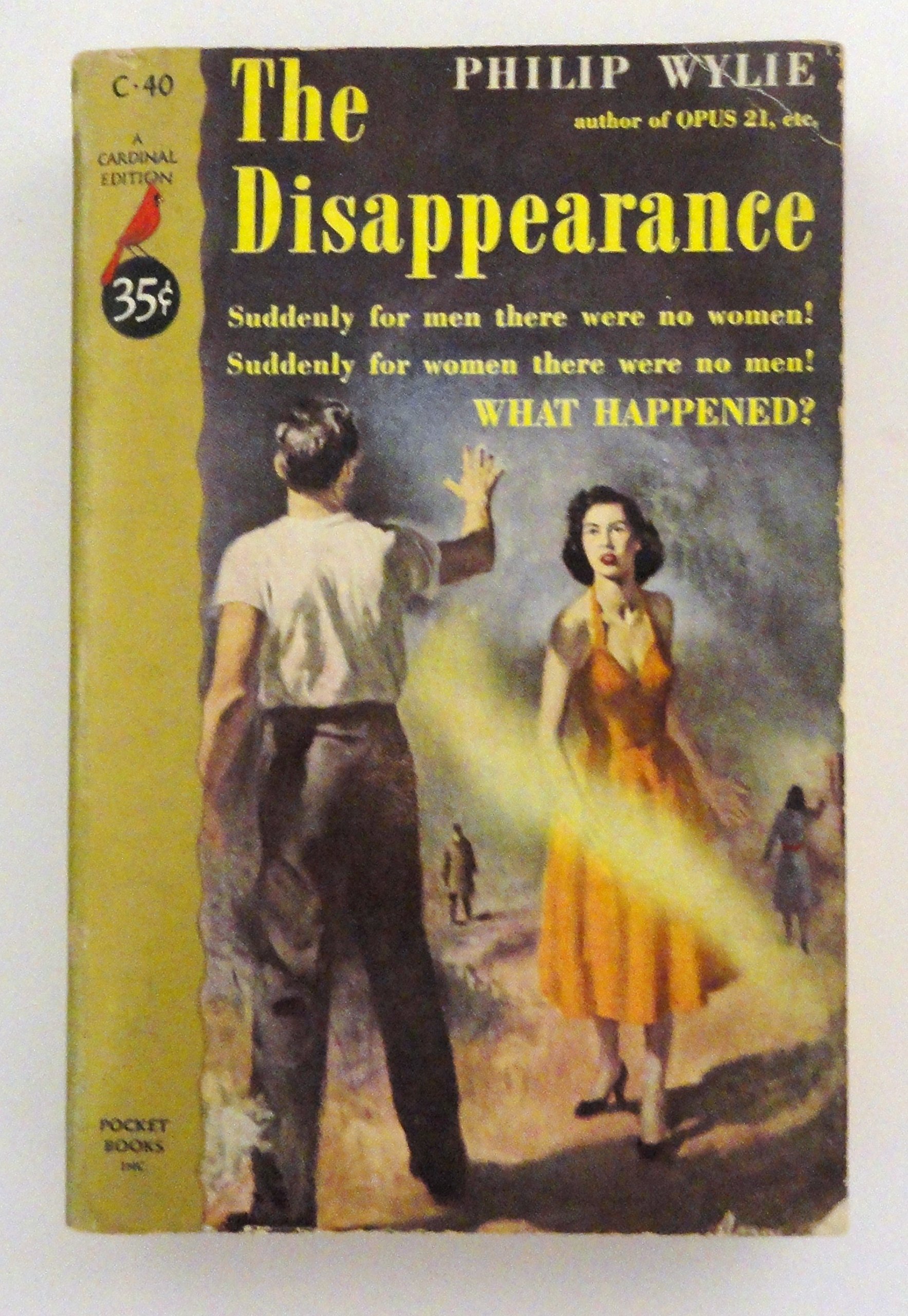

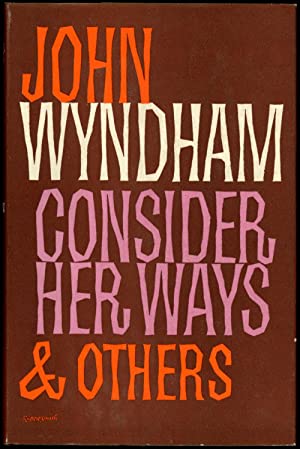

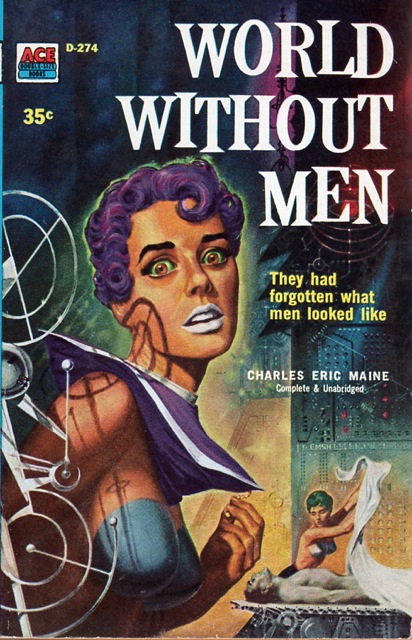

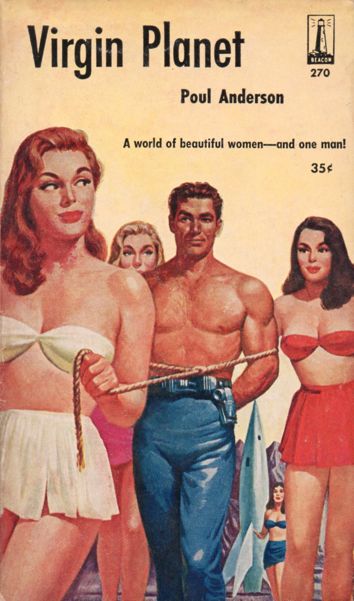

Just a few of the excellent SF anthologies currently available at your local bookshop

Whilst there have been teething troubles in a few of the stories, overall, I have enjoyed this season. It continues to show the value of the science fiction anthology series which, just like its paperback equivalent, offers a great way to explore a multitude of themes and ideas.

Whatever mysteries are unlocked by scientists, I have no doubt that SF writers will continue to find interesting questions to explore and there will be a place for this kind of television.

Long may it continue.

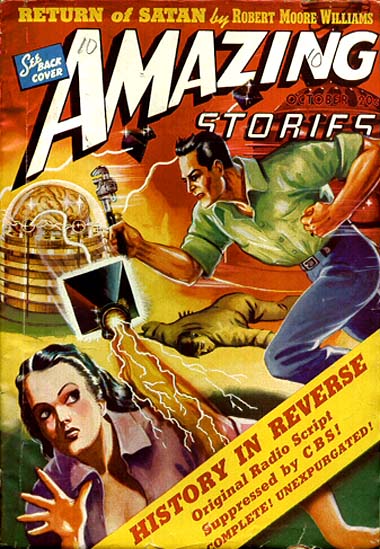

![[December 4, 1968] Sign Me Up (January 1969 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/amz-0169-cover-355x372.png)

![[November 6, 1968] Who's the one? (December 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/681106cover-471x372.jpg)

![[February 14, 1968] Triple John (February 1968 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/680214titles-672x372.jpg)

![[December 10, 1967] Give 'Em Hell, Harry! (January 1968 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/COVER-ART-3-672x372.jpg)

![[August 6, 1967] A Dark Future (<i>The Devil His Due</i> by Douglas Hill)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Devil-His-Due-2-306x372.jpg)

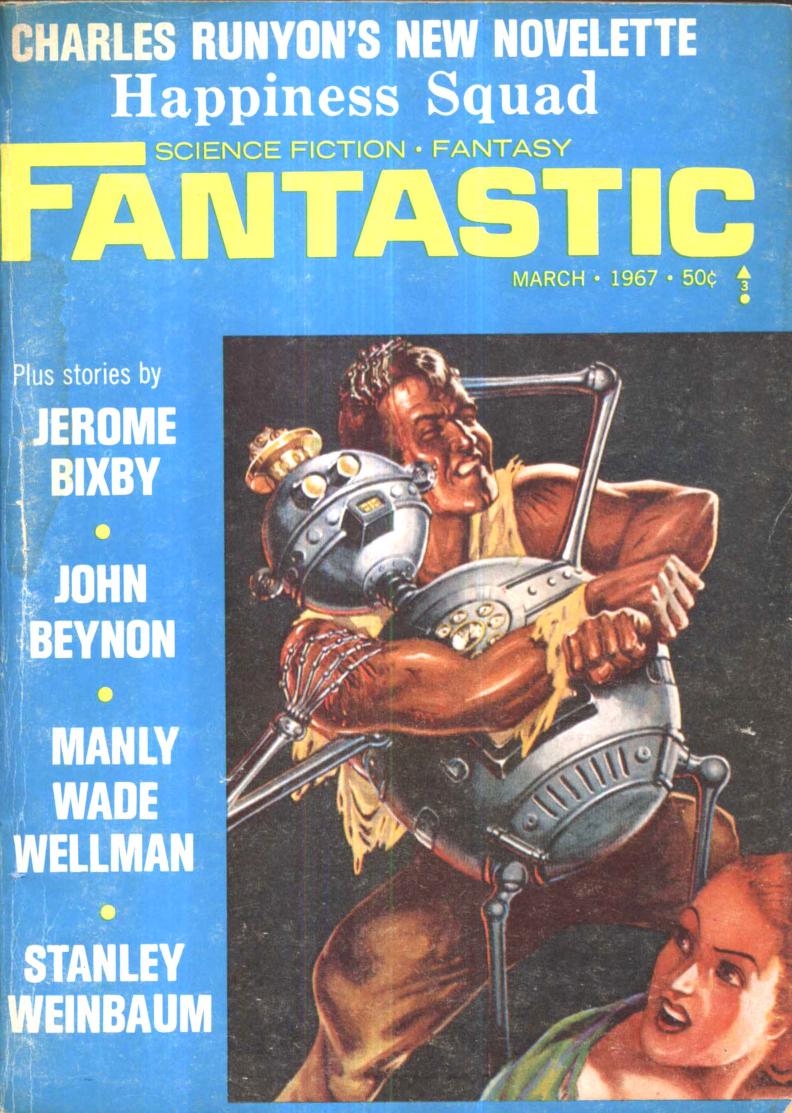

![[February 12, 1967] All's Fair in Love and War (March 1967 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Fantastic_v16n04_1967-03_LennyS-cape1736_0000-2-672x324.jpg)

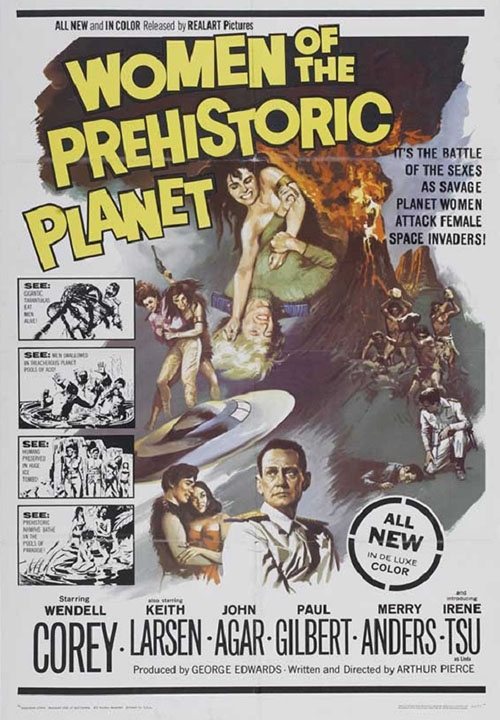

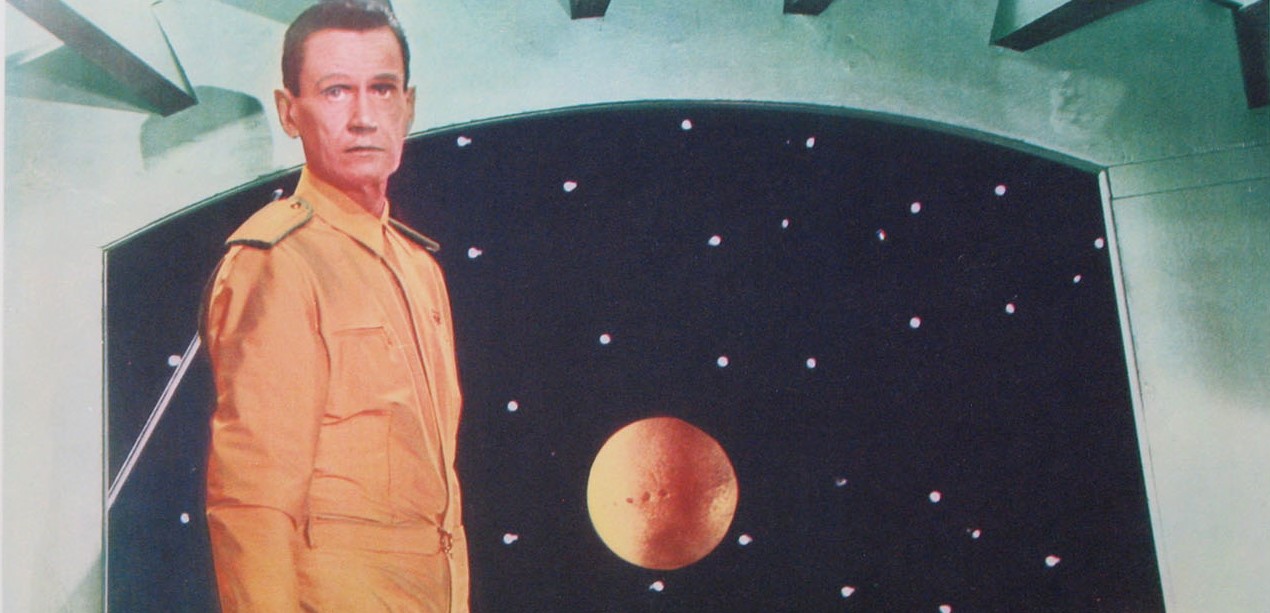

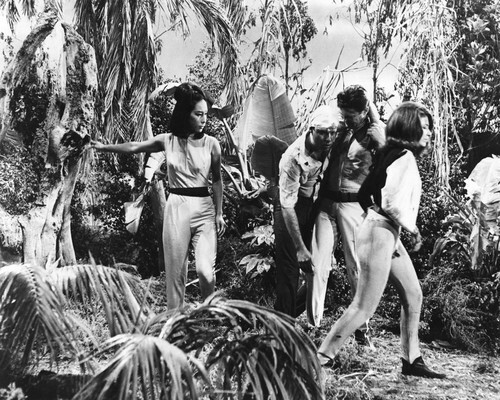

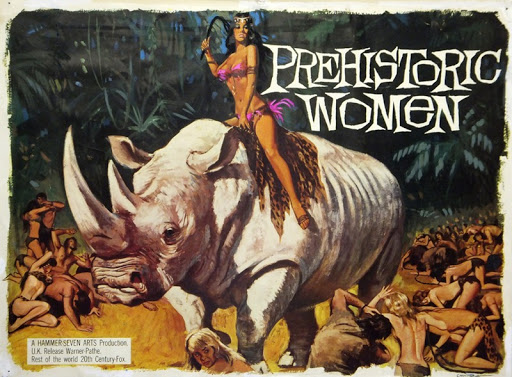

![[April 22, 1966] No Man's Land (<i>Women of the Prehistoric Planet</i> and Further Female Filled Fantasy Films)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/women_of_prehistoric_planet_1966-3.jpg)

![[January 18, 1966] New Discoveries of the Old (<i>Out of the Unknown</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Out-of-the-Unknown-Titles.jpg)

![[December 14, 1965] Expect the Unexpected (January 1966 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Fantastic_v15n03_1966-01_0000-3-672x372.jpg)