by Victoria Silverwolf

Days of Our Lives

I'm stealing the name of a new soap opera, due to premiere on NBC next month, because it sums up the way that past, present, and future came together in the news this month.

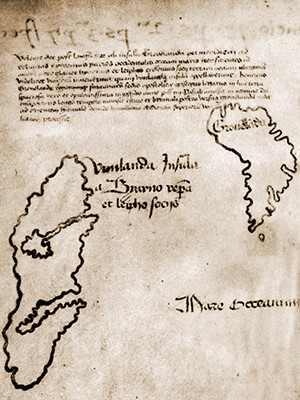

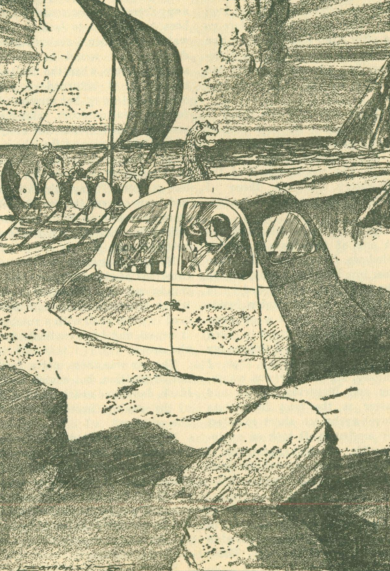

Yale University put an item known as the Vinland Map on public display on October 12. This is a map of the world, said to date back to the Fifteenth Century, which seems to indicate that Norsemen visited the Americas long before Christopher Columbus. In case you're wondering about the date, it was Columbus Day, in a nice bit of irony.

A detail of the Vinland Map. That's Greenland to the right, and a chunk of North America to the left.

As you might expect, there's controversy over whether this is the real thing or a forgery. Today, nobody knows for sure if this visitor from yesterday is genuine, but maybe we'll find out tomorrow.

If authentic, the Vinland Map is a voice from the past. In a similar way, folks in the present are trying to send a message to the future.

On October 16, the penultimate day of the New York World's Fair, a time capsule was lowered into the ground. (A similar object was buried nearby, during the 1939 World's Fair.) It is scheduled to be opened in the year 6939. (I'm a little skeptical as to whether such a thing can really survive and be found nearly five thousand years from now, but I like the idea.) The contents include . . . well, see for yourself.

People in that distant era will also know that we weren't very careful about spelling.

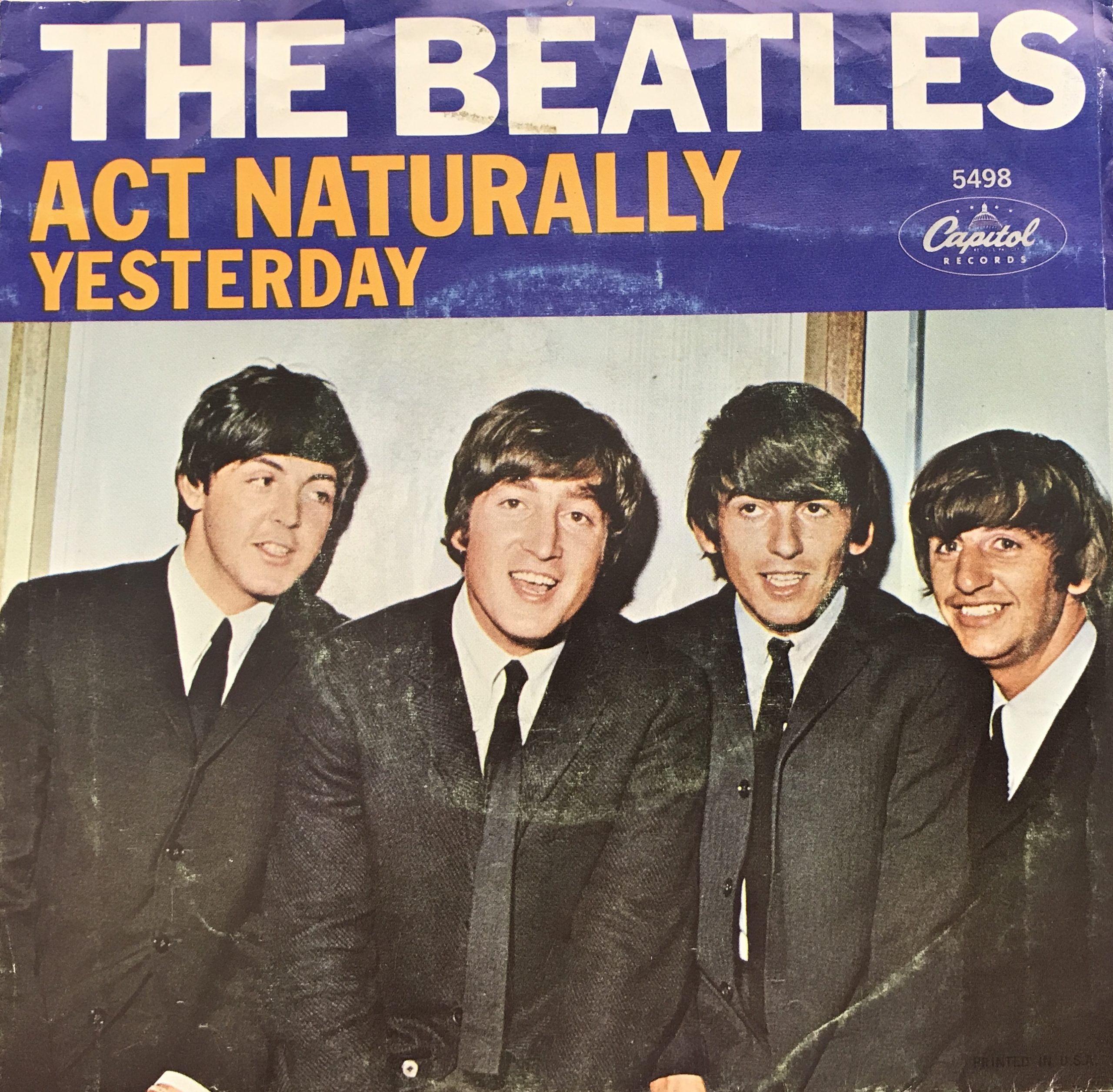

The Beatles seem destined to represent the artistic achievements of our time, if somebody actually finds the time capsule, opens it, and figures out how to play a record. They are once again at the top of the American popular music charts this month, and show no signs of leaving that position any time soon.

The latest smash from the Liverpool lads is, appropriately, called Yesterday. Unlike their other hits, it's a slow, melancholy song about lost love. Paul McCartney plays acoustic guitar and sings, backed by a string quartet. The other Beatles do not perform on the record, so it's really a McCartney solo performance.

By the way, Act Naturally is a remake of a Number One song by Buck Owens. The Beatles go Country-Western!

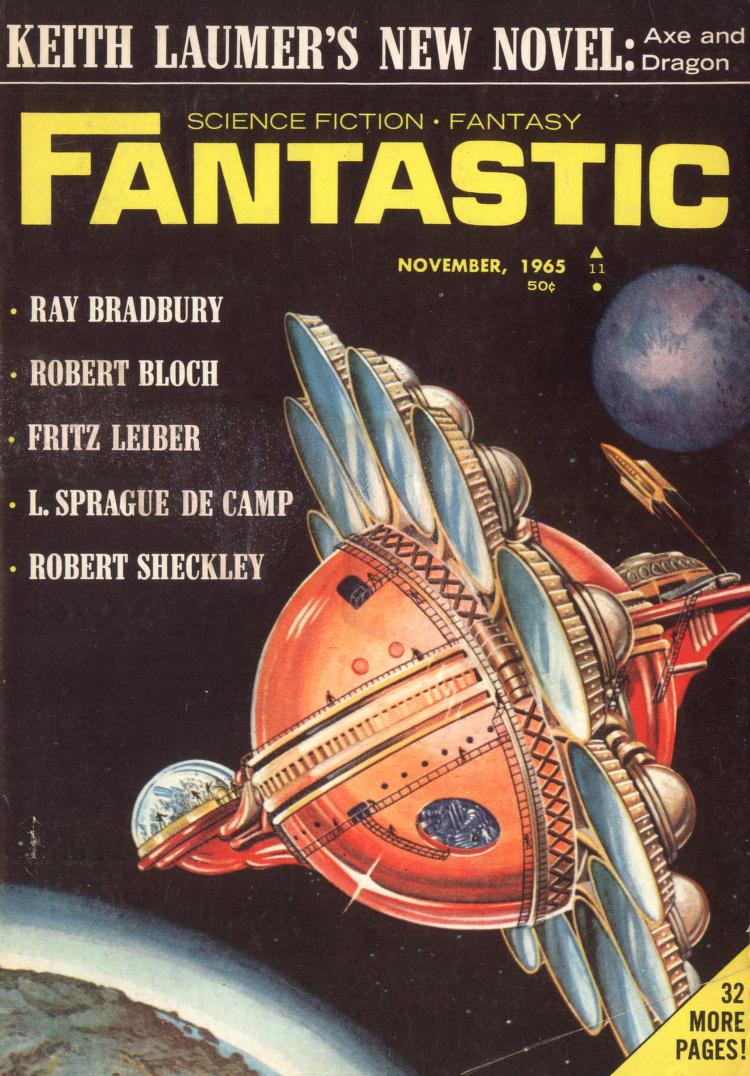

Flipping Through the Calendar

Given the peculiarities of the publishing business, it's no surprise that I'm reading the November issue of Fantastic in October. With their policy of filling about half the magazine with reprints, it's also not a shock to discover that we go back in time to fill up the pages. First up, however, is a new story set in a strange world that mixes up the past and the present.

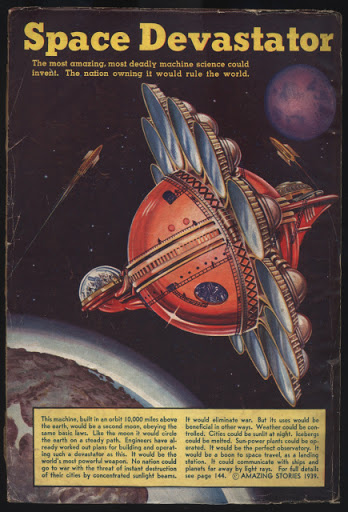

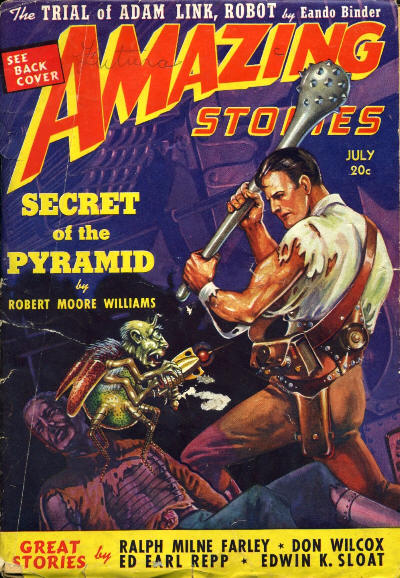

Cover art by Julian S. Krupa. It's actually taken from the back cover of the July 1939 issue of Amazing Stories.

Look familiar? We'll hear more about the Space Devastator later.

Axe and Dragon (Part One of Three), by Keith Laumer

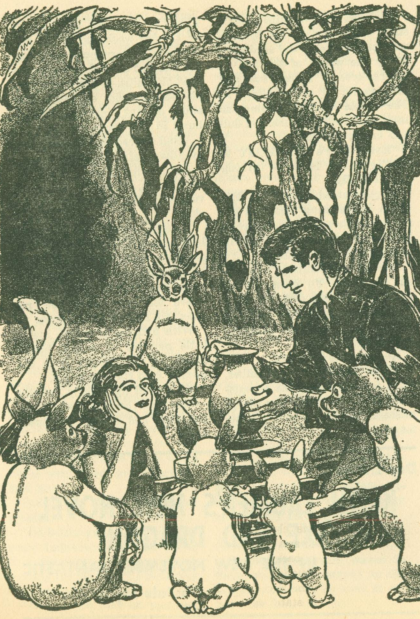

Illustrations by Gray Morrow.

Our hero is one Lafayette O'Leary, an ordinary working stiff, living in a crummy boarding house. He has a lot of intellectual curiosity, performing experiments in his tiny room and reading obscure books. He happens to find a Nineteenth Century volume on hypnotism, and learns about a technique whereby he can experience a dreaming state, while remaining aware that he is dreaming, and exercising some control over it.

(This isn't so crazy a premise as it might seem. More than fifty years ago, the Dutch psychiatrist Frederik Willem van Eeden coined the term lucid dream for such states of mind.)

Of course, he gives it a try. He winds up in a world that seems to be a bit medieval, a touch Eighteenth Century, a tad modern, and partly straight out of a fairy tale. The limitations on his ability to alter this dream world — if that's what it is — show up when he tries to give himself a set of fancy modern clothes, and winds up dressed like somebody in a swashbuckling movie.

Lafayette, ready for action.

At first, he enjoys the situation, happily replacing the lousy wine in a tavern with fine Champagne. Thought to be a wizard, he gets mixed up with the local equivalent of the cops. Still thinking this is just a dream, he tries to disappear, with only partial success.

Our hero tries to vanish, but can't quite do it.

Lafayette winds up in the palace of the King, where he is thought to be a prophesized hero, destined to save the realm from an ogre and a dragon. He also meets the King's magician, who seems to know more about what's going on than he admits. For one thing, he's responsible for the steam-powered coaches and electric lights in this otherwise nontechnological world.

The magician looks on as Lafayette admires himself.

Eventually, our hero meets the King's beautiful daughter, as well as the master swordsman who is her current boyfriend. Jealousy rears its head, and a challenge to a duel arises.

Lafayette assumes that his opponent, like everybody else in this world, is just a product of his imagination. Therefore, he reasons, the foe can't really be any better with a sword than he is. It looks like he might be in for an unpleasant surprise.

Tune in again for the next exciting chapter!

So far, at least, the tone of this novel is very light. Laumer almost seems to be parodying his own tales of the Imperium, with the protagonist finding himself in alternate realities. Unlike those serious stories, this one is a comedy. The people inhabiting the dream world speak in a mixture of archaic language and modern slang. The police are about as effective as the Keystone Kops. It's entertaining enough to keep me reading, but hardly profound.

Three stars.

Tomorrow and Tomorrow, by Ray Bradbury

The rest of the magazine consists of stuff from the old days, both the prose and the art. First we have a piece with a title that is fitting for my chosen theme. It comes from the May 1947 issue of Fantastic Adventures.

Cover art by Robert Gibson Jones, for what looks like a very odd story.

The protagonist is a would-be writer, reduced to pawning his typewriter due to his failure to find his way into print. (Surely based on the author's own early years, I assume.) He comes home to find a strange device. It sends him messages from the far future.

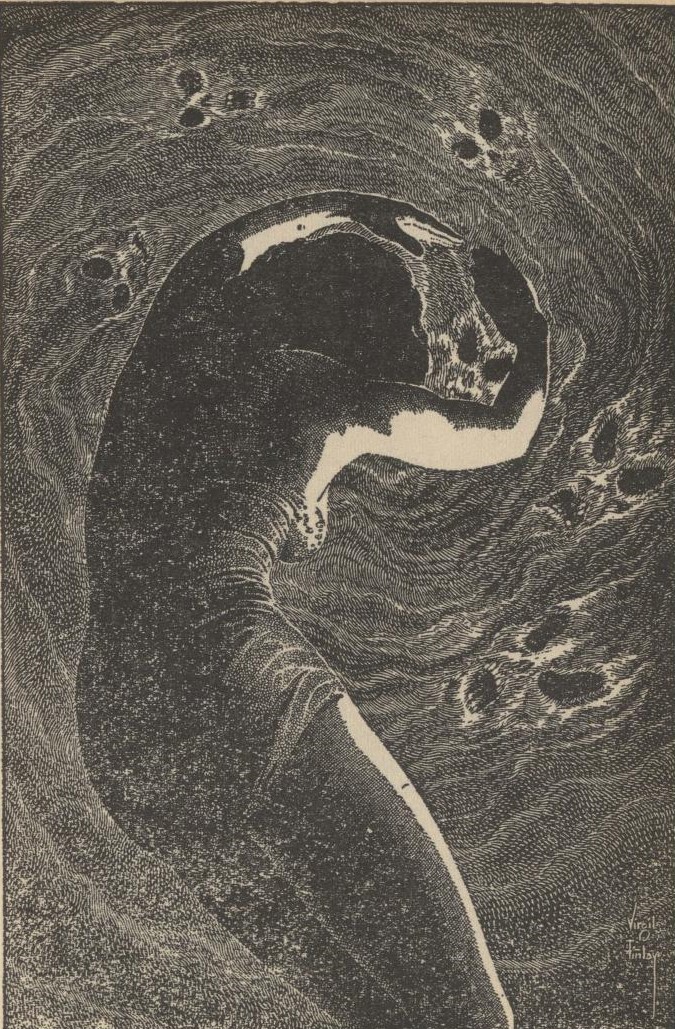

Illustration by Virgil Finlay.

Tomorrow's world is a dreary place, under the rule of a brutal dictator. A woman sent the machine back in time, insisting that the writer kill the remote ancestors of the tyrant. If he doesn't, the woman will be executed. If he does, the future will change, and she won't remember him at all. Since he's fallen in love with her, he will lose her either way. Besides this dilemma, he faces the moral crisis of murdering two innocent people.

This early work shows Bradbury developing his style, although it is not yet fully formed. You may think that's a good thing or a bad thing. Either way, it's got some emotional appeal, some passages of poetic writing, some implausibilities, and some lapses in logic. The ethical problem at the heart of the story — would you kill Hitler's ancestors? — is an important one, but here it's mostly used as a plot point.

Three stars.

I'm Looking for "Jeff", by Fritz Leiber

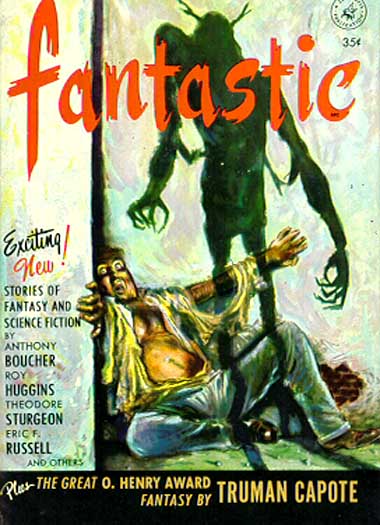

From the Fall 1952 issue of Fantastic comes this horror story, created by a master of the macabre (and other things.)

Cover art by Leo Summers. The Capote story is his very early work Miriam, which is a fine, eerie tale.

A bartender claims that a mysterious woman shows up regularly, although the owner of the joint can't see her. The reader is aware right from the start that she's a ghost.

Illustration by Emsh.

She uses her feminine wiles to pick up a customer, offering her affection in return for a promise to do something particularly violent to somebody named Jeff. The fellow, entrapped by her seductive charms — even the scar that runs across her face doesn't mar her beauty — agrees. He encounters Jeff, and makes a terrifying discovery.

There are no surprises in this variation on the classic theme of vengeance from beyond the grave. What elevates it above the usual ghost story is truly fine writing. The woman's first appearance, when she is a barely detectable wisp, is particularly fascinating.

Four stars.

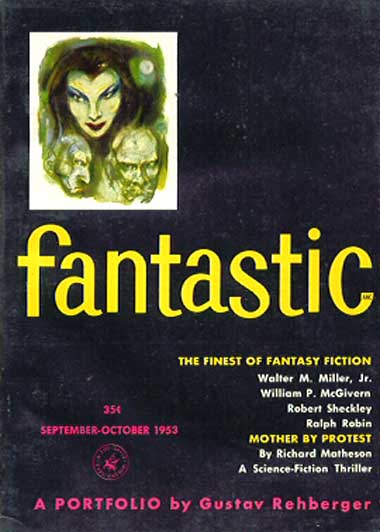

Wild Talents, Inc., by Robert Sheckley

The September/October 1953 issue of Fantastic supplies this comic yarn.

Cover art also by Leo Summers, what little you can see of it.

As you'd expect, the company named in the title deals with people who have psychic powers. It's pretty much an employment agency for such folks. Their latest client presents a problem.

Illustration by Emsh

It seems the fellow can observe anyone, at any location. Unfortunately, he's very much an oddball. His only interest is in recording their sexual activities in excruciating detail. The guy in charge of the company has to figure out a way to protect the public from this Peeping Tom, while making use of his peculiar ability in an acceptable way.

The whole thing is pretty much a mildly dirty, mildly clever, mildly amusing joke. You might see it as a spoof of the kind of psi-power stories that appear in Analog far too often. A minor effort from an author who is capable of much sharper satire.

Two stars.

Tooth or Consequences, by Robert Bloch

Another comedy, this time from the May 1950 issue of Amazing Stories.

Cover art by Arnold Kohn

It starts off like a joke. A vampire walks into a dentist's office . . .. It seems even the undead need to have their cavities filled. The vampire also swipes blood from the supply kept refrigerated in the same medical building. When the red stuff is then secured under lock and key, to prevent further thefts, the vampire tells the dentist he better get some of it for him, or else. There's a twist at the end you may see coming.

I suppose there's a certain Charles Addams appeal to the image of a fanged monster sitting in a dentist's chair. Otherwise, there's not much to this bagatelle.

Two stars.

The Eye of Tandyla, by L. Sprague de Camp

We go back to the May 1951 issue of Fantastic Adventures for this sword-and-sorcery yarn, one of a handful of stories in the author's Pusadian series. (The best-known one is probably the novel The Tritonian Ring, also from 1951.)

Cover art by Robert Gibson Jones

The setting is far back in time, long before recorded history. (The story goes that de Camp wanted to create a background similar to the one appearing in Robert E. Howard's tales of Conan, but in a more realistic fashion.) A wizard and a warrior must steal a magical gem from the statue of a goddess for their King, or be executed. Their plan involves disguising themselves with sorcery and sneaking into the place.

Illustration by Virgil Finlay.

To their amazement, it proves to be really easy to grab the jewel. So simple, in fact, that they smell a rat. They cook up a scheme to put the gem back in its place, steal a similar one from another place, and present that one to the King instead. Complications ensue.

You can tell that this isn't the most serious story in the world. The plot resembles a farce, with its multiple confusions and running back and forth. It's got the wit often found in Fritz Leiber's work of this kind, but not quite the same elegance. I'd say it's above the level of John Jakes, or even — dare I say it? — Howard himself, if not quite up to the very high standard of Leiber.

Three stars.

Close Behind Him, by John Wyndham

The January/February issue of Fantastic is the source of this chiller.

Cover art by Robert Frankenberg. The so-called new story by Poe is actually Robert Bloch's completion of a fragment.

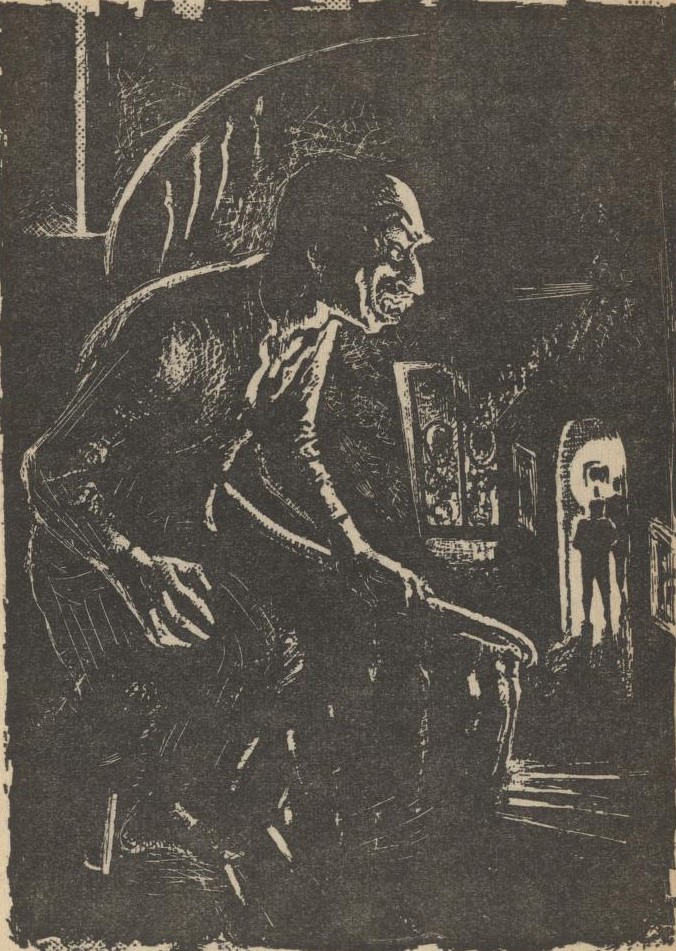

Two crooks rob the house of a very strange fellow. The guy catches one of them in the act, so the hoodlum kills him.

Illustration by Paul Lundy.

The pair make their getaway, but are followed by blood-red footprints wherever they go. You can bet things won't go well for them.

This is a pretty decent horror story, nicely written, although — once again! — not up to the level of Fritz Leiber, particularly since we've got an example of his excellent work in the field of tales of terror in this very issue.

Three stars.

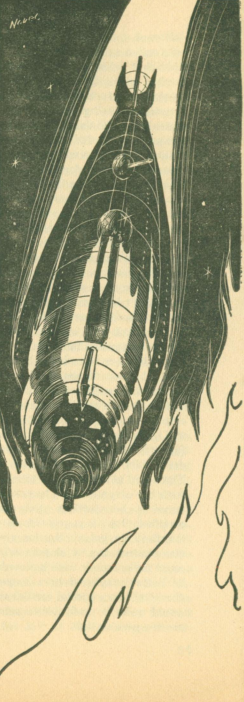

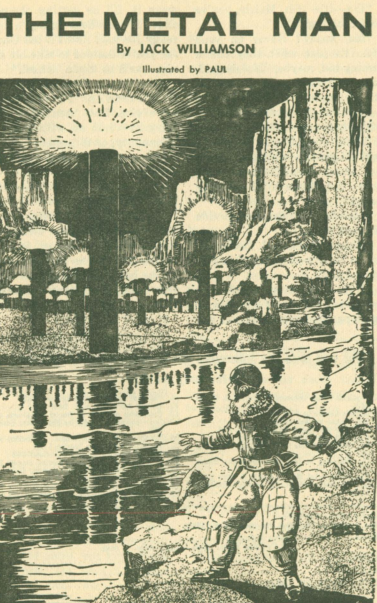

Space Devastator, by Anonymous

I'm not sure if I should even mention this tiny article, excerpted from the pages of the July 1939 issue of Amazing Stories.

Cover art by Robert Fuqua.

Anyway, it's less than a page long, and speculates about a huge station in orbit, equipped with a bunch of big mirrors.

Illustration by Julian S. Krupa

The notion is that such a thing could destroy entire populations from space by focusing the sun's rays and burning up cities. Casual mention is made of the fact that it could supply solar energy as well. I suppose it's imaginative for 1939, but it's so short — the original version was probably somewhat longer — that you can't get much out of it.

Two stars.

What Day is Good for You?

Today comes out a big winner over Yesterday and Tomorrow in this month's Fantastic. Leiber's contemporary ghost story is clearly superior to tales set in the future or in the legendary past. Otherwise, this isn't that great an issue, ranging from OK to below average.

You might well get more entertainment out of an award-winning film, such as this Italian comedy, which got the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film last year. Sophia Loren plays three different women, and Marcello Mastroianni three men, in a trio of lighthearted tales of love.

For some reason, every poster I've seen for this movie features Loren in her underwear. I wonder why that might be.

And you'll definitely enjoy the next exciting musical guest episode of The Journey Show, October 24 at 1PM Pacific!

![[October 22, 1965] Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow (November 1965 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Fantastic_v15n02_1965-11_Lenny_Silv3r_0000-2-672x247.jpg)

![[September 12, 1965] So Far . . . Well, Fair (October 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/amz1065-cover-497x372.png)

![[May 10, 1964] STUCK IN THE MIDDLE (the June 1964 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/640510cover-672x372.jpg)