by Gideon Marcus

We've got a whopping ten titles for you to enjoy this month. Part of it is the increased pace of paperback production. Part is the increased number of Journey reviewers on staff! Enjoy:

Double, Double, by John Brunner

From the author of Stand on Zanzibar, and also a lot of churned-out mediocrity, comes this mid-length novel. Can it reach the sublimity of last year's masterpiece, or is it a rent-payer? Let's see.

The band "Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition" (great name, that) have a bit of a Be-in on a deserted beach south of London. Their frivolity is marred by the appearance of a flight-suited zombie, half his face eaten away.

Strange happenings compound: the lushy Mrs. Beedle, who lives in a wreck of a home by the beach, suddenly starts appearing in two places at once. Those who encounter her find themselves doused with some kind of acid. Meanwhile, Rory, a DJ on the pirate radio ship Jolly Roger, hauls up a fish on his line that transforms halfway into a squid before breaking free.

The local constabulary, as well as the scientific types in the vicinity, are increasingly alarmed and then mobilized, as the true nature of what they're dealing with is determined: an alien or mutated being with the power to digest and mimic anything it encounters.

In premise, it's thus somewhat akin to Don A. Stuart's (John W. Campbell Jr.) seminal "Who Goes There". In execution, it's not. The rather thin story is developed glacially, with lots of slice-of-life scenes that are not unpleasant to read, but don't add much. Indeed, one could argue that it is possible to unbalance things too far in the direction of "show, don't tell"—Double, Double is written almost like a screenplay, with endless little cliff-hangers, and always from the point of view of the various characters.

Beyond the writing, the premise is fundamentally flawed: digestion is never 100% efficient. Heck, I don't think it's 10% efficient. And this creature can not only digest but duplicate, down to memories? Color me unconvinced. Also, we are lucky that it chose to come to land as quickly as it did—if it had just stayed in the sea, all of the sea life in the world would have been these… things… in very short order.

All told, this is definitely a piece written for the cash grab, perhaps even a recycled, rejected script for the TV anthology Journey to the Unknown. It's not a bad piece of writing, but I'll be donating it to my local book shop when I'm done.

Three stars.

by Brian Collins

For my first book reviews as part of the Journey, I got some SF and fantasy in equal measure. Neither are really worth it, but here we can see the difference between a deeply flawed novel and one that is virtually impossible to salvage.

Omnivore, by Piers Anthony

I know it’s only been a few months since Piers Anthony hit us with his second novel, Sos the Rope, but he has already given us another with Omnivore. That’s three novels in two years! For all his faults, you can’t say he’s lazy. It’s quite possible that in thirty years there will be more Piers Anthony novels than there are stars in the sky.

Omnivore is a planetary adventure, not dissimilar from what Hal Clement or Poul Anderson would write, but with some of those “lovable” Anthony quirks. Here’s the gist: A superhuman agent named Subble is sent to investigate three explorers who have returned to Earth from the “dangerous but promising” planet Nacre, each with his/her trauma and secrets as to what happened. Why did eighteen people die while exploring Nacre prior to these three, and what did they bring back with them? There’s Veg, who as his nickname suggests is a vegetarian; Aquilon, an emotionally fraught woman who now has a case of shell shock; and Cal, gifted with a brilliant intellect but cursed with a frail body. Veg and Cal love Aquilon and Aquilon loves both men. Romantic tension ensues. Anthony pulled a similar love triangle in Sos the Rope, but for what it's worth this one is not quite as painful.

Nacre itself is the star of the show, and it would not surprise me if Anthony were to return to this setting in the future. It’s a fungus-rich planet in which the land is covered in an unfathomable amount of “dust”—spores from airborne fungi. There’s so much airborne fungi, in fact, that the sun has been more or less blocked out, and the animal life has adapted not only to low-light conditions but to move about with only one (big) eye and one limb. Clement would have surely treated this material with more scientific enthusiasm, but Clement sadly is no longer producing his best work and this novel is a serviceable substitute for the not-too-discerning.

Omnivore is Anthony’s best novel to date; unfortunately it’s still not good. There are two crippling problems here. The first is that Anthony simply cannot help himself when it comes to writing women unsympathetically, and the first section of the novel (there are four, each focusing on a different character) is the worst. Veg, while heroic, is unfortunately a woman-hater. I don’t necessarily have an issue with characters having unsavory flaws, but the problem is that this dim view of women bleeds into the rest of the novel to some degree. It should come as no surprise that Aquilon, the sole female character, is also the only one driven purely by emotions as opposed to intellect. Subble himself may as well be a robot, but Anthony writes him as a human so that he can a) take drugs, and b) seduce Aquilon.

The second is that it’s clear that this novel is About Things, but I can’t figure out what those Things could be. There is obvious symbolism at work. The trio of explorers play off of elements (herbivore/carnivore/omnivore, brains/brawn/beauty, and so on), but I’m not sure what statement is being made here. This is especially glaring in a year where we got many SF novels that are About Things; indeed 1968 might’ve been the year of SF novels that try to say Something Very Important. Omnivore might’ve been fine in the hands of a Clement or Anderson, but rather than be true to itself (an Analog-style adventure yarn), it has delusions of importance. It doesn’t help that Anthony gives us a puzzle narrative, but then takes seemingly forever to tell us what the puzzle actually is. The solution, thus, is unsatisfying.

At the rate he’s progressing, Anthony may be able to pen a decent novel in another few years. Two out of five stars, maybe three if it had caught me in a very forgiving mood.

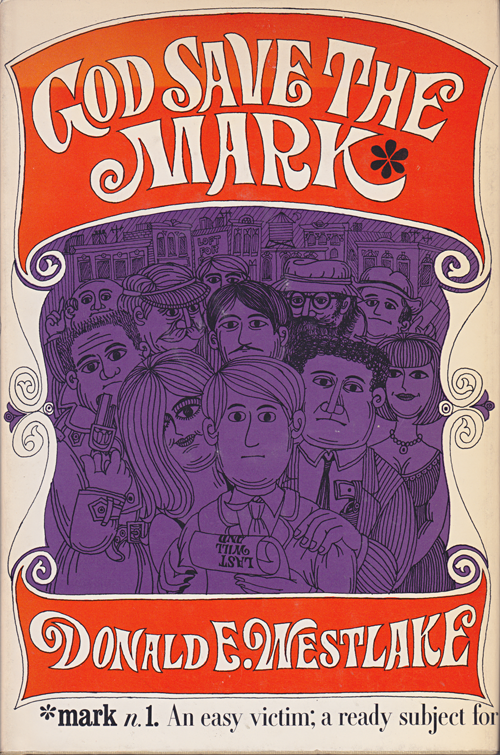

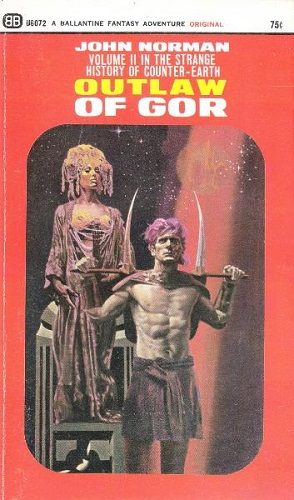

Swordmen of Vistar, by Charles Nuetzel

Cover by Albert Nuetzell

Now we have the latest in what's proving to be an avalanche of heroic fantasy releases, and this one is simply painful to read. We know something is amiss just from looking at the title; to my recollection Nuetzel never used "swordman" or "swordmen" in the novel itself, which leads me to wonder what he could've been thinking. The writing between the covers is no less clumsy.

Thoris is a galley slave, in an ancient world not far off from the mythical Greece of Perseus and Pegasus, when he and the princess Illa find themselves possibly the only survivors of a shipwreck. Thoris falls in love with Illa before the two have even had a full conversation together. They first arrive at an island of cannibals before escaping, only to fall into the clutches of the tyrannical Lord Waja and his sword(s)men of Vistar. Also imprisoned is the wizard Xalla, who is father to a woman named Opil whom Thoris had saved earlier. With no other options, Thoris makes a deal with Xalla to vanquish Waja and then free the wizard—on the ultimate condition that Thoris also take Opil as his bride.

The back cover compares Thoris to Conan the Cimmerian and John Carter of Mars, and indeed Swordmen of Vistar is supposed to be a rip-roaring adventure with a damsel in distress, a morally ambiguous wizard, and a giant snake. One problem: the prose is some of the most ungainly I've ever laid eyes on. Edgar Rice Burroughs and Robert E. Howard were not tender in their use of the English language, but they had a real knack for plotting which Nuetzel lacks. This is a 220-page novel and surprisingly little happens in it. I hope you still like love triangles, because this novel also has one. Lord Waja and his top henchmen are defeated by the end of the eleventh chapter, but we still have two more to go with Opil as the final obstacle. We need to pad out this already-short book, obviously.

With how much I've been reading about love triangles, I think God may be telling me to try acquiring a second girlfriend. If I were Thoris I would be stuck with a tough choice. Do I pick the tough-minded woman who clearly appreciates my swordsmanship, or the haughty princess who's been degrading me for much of the novel? Sure, the former threatens to kill me if I refuse her, but nobody's perfect.

By the way, Nuetzel may be excusing the awkward prose by stating in the preface that the Thoris narrative is a translation of an ancient manuscript that some academic had written up and given to him. Unfortunately academics, by and large, are terrible writers with no ear for English, and this shows in the "translation." It doesn't help that yes, this is derivative of the John Carter novels, along with a few other things; and while Robert E. Howard's Conan stories are often About Something, Nuetzel doesn't really have anything to say. If you've read hackwork in this genre then the good news is that you've already read Swordmen of Vistar, and so can save yourself the trouble of buying a copy.

Basically worthless, although the illustrations (courtesy of Albert Nuetzell) are at least decent. One out of five stars.

by Jason Sacks

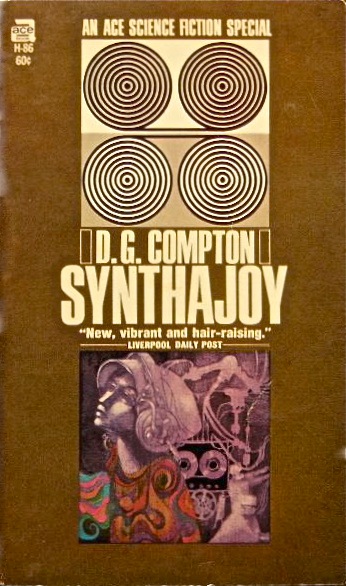

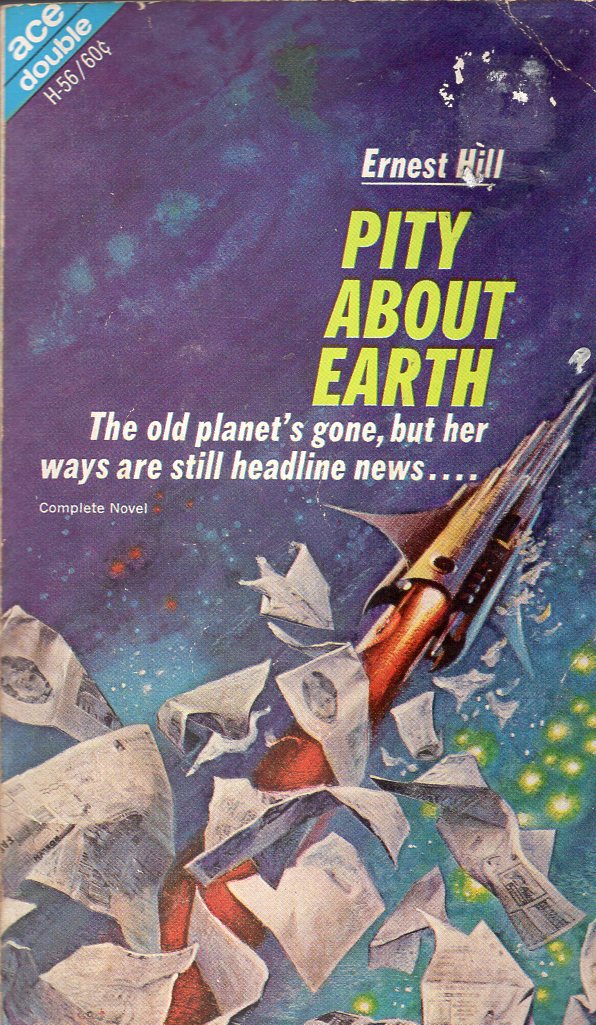

The Star Venturers by Kenneth Bulmer

Bill Jarrett is a galactic adventurer, a man who spans the stars to find excitement, glory and money. He’s a flirt and a fighter and the kind of guy who can work himself out of situations. But when Jarrett gets abducted, has a mind-controlling creature strapped to his head, and is sent to overthrow a man who he’s told is a dictator, Jarrett finds himself in a situation he might not be able to win.

Well, yeah, of course, Jarrett does end up winning in the situation he finds himself in, with the help of his friends and a few mechanical contrivances. Because of course he does. As a galactic adventurer, that’s what you might expect from him.

The Star Venturers is an entertaining Ace novel, a quickie star-spanner with a handful of ideas which might stick to your brain. Author Kenneth Bulmer occasionally throws in a small element of satire or self-awareness which enlivens the plot; there’s a bit of a feeling of the author kind of winking at us as he tells this story. But there’s not nearly enough of that stuff to make this book stand out.

Bulmer does play a bit with an interesting concept, the sort of self-learning machine, a kind of artificially intelligent creature called a frug (which Jarrett nicknames Ferdie the Frug) which is placed on a person’s forehead like a headband and which compels the person to follow orders lest they feel horrific agony.

Bulmer takes pains to imply that the device is both mechanical and semi-sentient, a kind of uncaring vicious machine which Jarrett sometimes reasons with and almost treats like a pet – if the pet was a giant tumor which could only cause pain, that is. This idea of artificial intelligence dates back at least to the first robot stories, but the author gives the idea a fresh coat of paint here, and that concept is a real highlight for me.

Other than that, this is a pretty basic space fantasy Ace novel, which is entertaining for its two hour reading time but which will have you quickly flipping over to read the novel by Dean Koontz on the other side. At least it’s not About Things or Very Important. Instead The Star Venturers is just forgettable.

2.5 stars

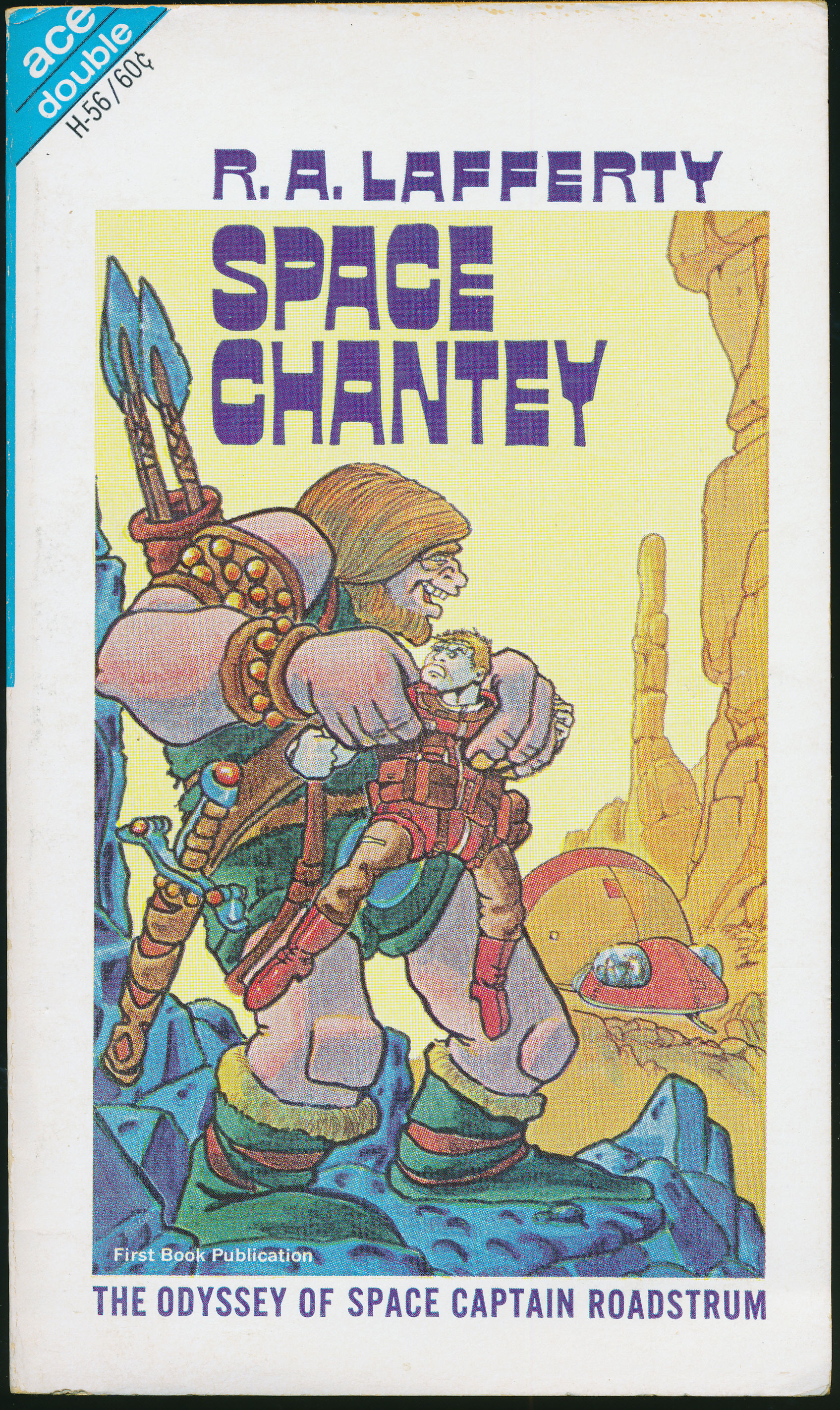

The Fall of the Dream Machine by Dean Koontz

On the other hand, the flip side of this Ace Double is pretty memorable. Dean R. Koontz, an author new to me, has delivered a fascinating satire of a world which is easy to imagine and just as easy to dread.

In the near future, post apocalyptic America, television rules our world. All the people in America live for a special show which all can experience viscerally. That TV show, called The Show, has seven hundred million subscribers. Those subscribers watch a continuing story, kind of a soap opera, about the characters on the screen. But they don't just watch the characters, they also feel the same emotions as the characters. They feel empathy and pain for the characters. In a real way the characters and viewers are bonded.

Because the actors are so well known, so much a part of their audience's lives, even the act of replacing an actor can be tremendously fraught with stress and worry. The act of leaving The Show can be freeing but also terrifying. And when lead actor Mike Jorgova leaves The Show, it makes his life much more complicated. He becomes untethered, is trained to become part of a revolution, and discovers the deeper frightening truths behind a world he scarcely understood.

Young author Dean Koontz delivers a clever and exciting story which shows tremendous potential. He does an excellent job of creating his world in relatively few words, delivering character in just a few broad strokes and creating memorable villains and settings. The end action set-piece, for instance, is built with real suspense and ends with a thrilling struggle which is filled with energy.

Along with that aspect, young Mr. Koontz delivers two more elements which separate this book from many of its peers.

First, he paints a fascinating future which seems like a smart extension of McLuhan's concept that "the medium is the message." Koontz creates a TV show which feels like reality, in which the characters live in some semblance of real life while engaging in exaggerated, bizarre actions. That's a concept which feels all the more possible these days, with controversies about the Smothers Brothers and Vietnam dominating headlines about television in 1969.

Koontz also delivers a series of philosophical asides which discuss human evolution from village to society and the ways mass media both shrinks the world and expands our horizons. Nowadays we know everything about people who live across the world but nothing about the people who live next door to us, and that gap only promises to get wider. As our social networks grow, the strengths of our connections only shrink.

This is heady stuff for an Ace Double – and I've only touched on a few of the many ideas shared almost to overflowing here. In fact, the book is chockablock full of ideas but the ambition is a bit high for their achievement. Like many a new author, Koontz has many, many ideas he wants to explore but there are a few too many on display. Nevertheless, despite its thematic density, The Fall of the Dream Machine reads like a rocketship, hurtling ahead until it lands gracefully, sharing a thrilling journey for the readers.

Keep your eye on Mr. Koontz. I predict great things from him.

3.5 stars.

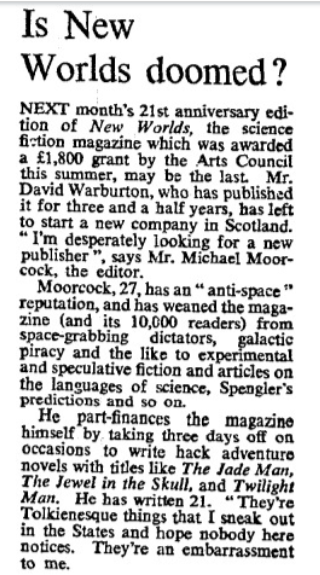

by Mx. Kris Vyas-Myall

Frontier of Going: An Anthology of Space Poetry, ed. By John Fairfax

Poetry has always had a strange place in science fiction. Long before appearing in Hugo Gernsbeck’s magazines, poets have been attempting to explore fantastic themes. However, in spite of their regular presence in almost every SFF periodical, and many fanzines, they rarely seemed to be talked about, nor are they represented in either the Nebulas or the Hugos (although we here give out Galactic Stars to them).

Enter John Fairfax and Panther publishing, who have put together this anthology of responses to the space age. The selection inside is varied. Some are original and some are reprints. Some are SFnal, some are fantastical, others closer to reality. And, as the editor puts it:

Some poets are optimistic about the space odyssey, others view it with cynicism…and other poets do not care if man steps into space or the nearest bar so long as human relations begin with fornication and end with death.

As this book contains almost 50 separate pieces, I cannot hope to cover them all here; rather I want to give an overview and highlight some of the best.

Possibly due to my natural cynicism, Leslie Norris’ poems were among my favorites. He is willing to engage deeply with the future, but believes the same problems we have down here will continue there. For example, in Space Miner we hear of the fate of those travelling to distant worlds for such a job:

He had worked deep seams where encrusted ore,

Too hard for his diamond drill, had ripped

Strips from his flesh. Dust from a thousand metals

Stilted his lungs and softened the strength of his

Muscles. He had worked the treasuries of many

Near stars, but now he stood on the moving

pavement reserved for cripples who had served well.

Just a small part of one of his moving poems that raise interesting questions about where we are headed.

Closely related is John Moat’s Overture I. His works concentrate less on the science fiction but still wonder if we are heading in the right direction:

That twelve years’ Jane pacing outside the bar,

Offering anything for her weekly share

Of tea; those rats now grown immune to death –

I ask you, in whose name and by what power

Have you set out to colonize the stars?

This is only an extract and continues in that fashion. It ponders if what we are bringing to other planets is something they would care for.

Not all are so negative. Some, instead, write about the wonder and artistic possibilities of space travel. Robert Conquest (who SF fans may know from his anthologies or short fiction in Analog) produces a Stapledon-esque epic among the stars in Far Out:

While each colour and flow

Psychedelicists know

As Ion effects

Quotidian sights

Of those counterflared nights.

Yet Conquest still asks within, what is the value of these views to the artist? A complex piece for sure.

There are probably only two other names you have a reasonable chance of recognizing inside: D. M. Thomas and Peter Redgrove, both for their occasional appearances in the British Mags. As you might expect these are among the most explicitly science fictional. For example, in Limbo Thomas gives us a kind of verse version of The Cold Equations, whilst Redgrove’s pieces are trains of thoughts of two common character types of SFF.

However, it should not be thought others have written repetitively on the theme. These poems include such diverse topics as the difficulties of copulation in space, how to serve tea on a space liner, the first computer to be made an Anglican bishop, and explorers getting absorbed into a gestalt entity.

The biggest disappointment for me are the poems from the editor. It is to be expected Fairfax would have a number of pieces inside but, unfortunately, they are among the most pedestrian. For example, his Space Walk:

Around, around in freefall thought

The clinging cosmo-astronaut,

Awkward and expensive star

Dogpaddles from his spinning car.

The poem has nothing inherently wrong with it, but it does not feel insightful, nor does it do anything experimental. It more feels like what would win a middle-school poetry competition on the Space Race. Probably deserving of a low three stars but little more.

I feel, at least in passing, I need to point out we have the recurring problem of the British scene. In spite of the number of poems contained within, none of the poets appears to be woman. There are no shortage of women poets, either in the mainstream or within the fanzines, so I find it hard to believe there were no good pieces available. Hopefully, this can be remedied in a future volume. The Second Frontier, perhaps?

Either way, this is still a fabulous collection. Of course, it will not be for everyone. Poetry is probably the most subjective form of literature, and not everyone likes to sit down to read more than forty poems in a row. However, the selection here is a cut above what we tend to see from our regular science fiction writers (looking at you, de Camp and Carter) and I hope it helps raise the form to higher standards and recognition.

Four Stars for the whole anthology with a liberal sprinkling of fives for the poems I have called out.

by Victoria Silverwolf

Four new novels suggest the seasons, at least for those of us living in the temperate regions of the northern hemisphere. Let's start with the traditional beginning of the year, as opposed to our modern January.

Spring is associated with youth. Our first novel is narrated by a teenager, and is obviously intended for readers of that age.

The Whistling Boy, by Ruth M. Arthur

Cover art by Margery Gill, who also supplies several interior illustrations.

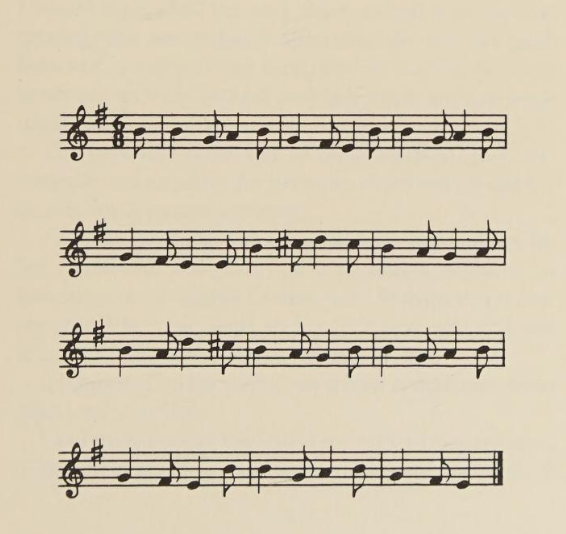

The first thing you see when you open the book is musical notation. The melody is said to be a very old French tune, and it plays a major part in the plot.

Those of you who can read music may be able to whistle along with the boy.

Christina, known as Kirsty, is a schoolgirl whose mother died a while ago. Her father remarried, this time to a much younger woman. Like many stepchildren, Kirsty resents her.

An opportunity to escape the awkward situation for a while comes when Kirsty gets a job picking fruit in Norfolk. She moves away from her home in Suffolk and lives with a kindly elderly couple.

Strange things start to happen when she hears music coming from an empty room next to her attic bedroom. She meets a local boy who experienced amnesia and sleepwalking when he stayed in the house. More alarmingly, he almost drowned when he walked toward the sea in a trance.

In addition to this mystery, which involves the supernatural, there are multiple subplots. Kirsty has to learn to get along with her young stepmother. A schoolfriend has no father, an alcoholic mother, smokes, admits to having tried marijuana, and is later arrested for shoplifting. One of her two young brothers suffers an accident.

Despite all this going on, and a dramatic climax, the novel is rather leisurely. The author captures the voice of her young narrator convincingly, and never writes down to her readers. There's a love story involved, and the book might be thought of as a Gothic Romance for teenage girls. In addition to this target audience, adults and even boys are likely to get some pleasure from it.

Three stars (maybe four for teenyboppers.)

Our next book takes its characters into a place of tropical heat.

Cover art by Kenneth Farnhill.

Two young men are hiking when they get lost in a storm. They wind up in a tiny village with only a handful of people living there. It seems that a dam under construction is going to flood the place, so most folks have moved out.

They spend the night in the home of an elderly couple whose son was killed in World War Two. (That may not seem relevant, but it plays a part in the plot.) The other inhabitants of the doomed village are an ex-military man, his adult son and daughter, a somewhat shady fellow, and the former showgirl who lives with him.

Things get weird when this quiet English village develops a tropical climate overnight. Bizarre plants, some like hot air balloons and some like birds, show up. The surrounding countryside changes into a land of earthquakes and volcanoes. What the heck happened?

We soon find out that people from a time thousands of years from now use time travel to transport folks hundreds of thousands of years into the future. Why? Because the future people face an all-encompassing disaster, and want to start human life all over again in the extreme far future.

(They only select folks in the past who were going to be wiped out of history anyway. The village was just about to be buried under a huge landslide, leaving no evidence behind.)

The rest of the book shows our reluctant time travelers exploring, figuring out a way to survive, and fighting among themselves. The two young women pair up with a couple of the men, but not in the way you might expect.

Near the end, the plot turns into a murder mystery, which seems a little odd. The conclusion is something of a deus ex machina. Otherwise, it's an OK read. The characters are interesting.

Three stars.

Fall is a time of nostalgia and anticipation. We gaze at the past, and ponder the future. Our next book features a lead character who has a lot to look back on, and plenty to concern him coming up.

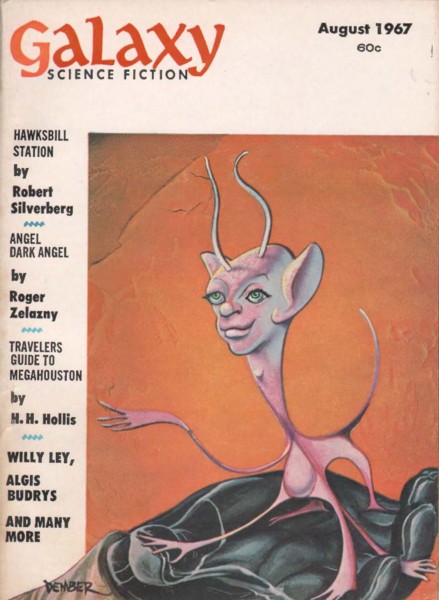

Isle of the Dead, by Roger Zelazny

Cover art by Diane and Leo Dillon.

The book takes its title from a famous painting by 19th century Swiss artist Arnold Böcklin.

The artist created several versions of the work. This is one of them.

Francis Sandow, our narrator, started off as a man of our own time. (There are hints that he fought in Vietnam, or at least somewhere in Southeast Asia.) He went on to travel on starships in a state of suspended animation, so he is still alive many centuries from now. In fact, he's one of the wealthiest people in the galaxy.

(Some of this is deduction on my part. The narrator only offers bits and pieces of his life throughout the text. The same might be said about the book's complex background. The author makes the reader work.)

Francis made his fortune by creating planets as an art form. If that isn't god-like enough for you, he's also an avatar of an alien deity, one of many in their pantheon. It's unclear if this is a manifestation of psychic power or a genuine case of possession. The mixing of religion and science in an ambiguous fashion is reminiscent of the Zelazny's previous novel Lord of Light.

Somebody sends Francis new photographs of friends, enemies, lovers, and a wife, all of whom have been dead for a very long time. He also gets a message from an ex-lover (still alive) stating that she is in serious trouble.

This sets him off on an odyssey to multiple planets, as he tracks down an unknown enemy. Along the way, he participates in the death ritual of his alien mentor. The climax takes place on the Isle of the Dead, a place he created on one of his planets as a deliberate imitation of Böcklin's painting.

The bare bones of the plot fail to convey the exotic mood of the book, or Zelazny's style. His writing is informal at times; in other places, he uses extremely long, flowing sentences you can get lost in.

As I've suggested, this novel requires careful reading. Stuff gets mentioned that you won't understand until later, so be patient. I found it intriguing throughout. If the ending seems a little rushed, that's a minor flaw.

Four stars.

Winter has its own special beauty, but it is often seen as a dismal time. The characters in our final book face a bleak future indeed.

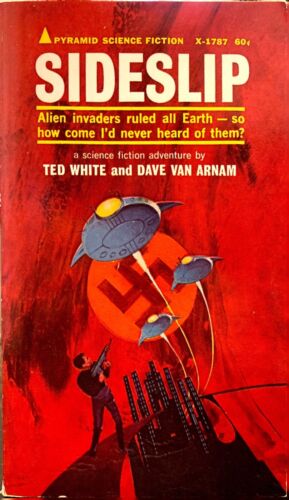

S.T.A.R. Flight, by E. C. Tubb

Uncredited cover art.

About fifty years before the novel begins, aliens arrived on Earth with what seemed to be benevolent intent. Well, you know what they say about Greeks bearing gifts.

The Kaltichs brought longevity treatments and advanced medical techniques that could replace any damaged organ. The catch is that Earthlings have to pay a high price for these things.

There's also the problem of overpopulation. The Kaltichs promised to give humans the secret of instantaneous transportation to a large number of habitable planets. It's been half a century, and we're still waiting.

Because the longevity treatments have to be renewed every ten years, and the Kaltichs deny them to anybody they don't like, Earthlings are subservient to them. We have to call them sire, and punishment with a special whip that inflicts extreme pain follows any transgression.

Our protagonist, Martin Preston, is a secret agent for S.T.A.R., the Secret Terran Armed Resistance. (I guess we're still not over the spy craze, with its love of acronyms.) The agency asks him to imitate a Kaltich and infiltrate one of their centers, which are off limits to humans.

(I should mention here that the Kaltichs are physically identical to Earthlings. That seems unlikely, but it's a plot point and we get an explanation later.)

Because the previous fellow who tried this had his hands cut off and sent back to S.T.A.R., Martin understandably refuses. An incident occurs that changes his mind. With the help of a brilliant female surgeon (who, like most of the women in a James Bond adventure, is gorgeous and sexually available), he sets out on his dangerous mission.

What follows is imprisonment, torture, escape, killings, double crosses, and the discovery of the big secret of the Kaltichs, which you may anticipate. The book is similar to a Keith Laumer slam bang thriller, if a little more gruesome. Hardly profound, but it sure won't bore you.

Three stars.

There you have it, folks. Take ten and enjoy all the new novels coming out. We'll be back next month to help you figure out which ones to put at the top of the pile.

![[January 14, 1969] Ten for the road (January Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/690114covers-672x372.jpg)

Cover by Gabi Nasemann

Cover by Gabi Nasemann

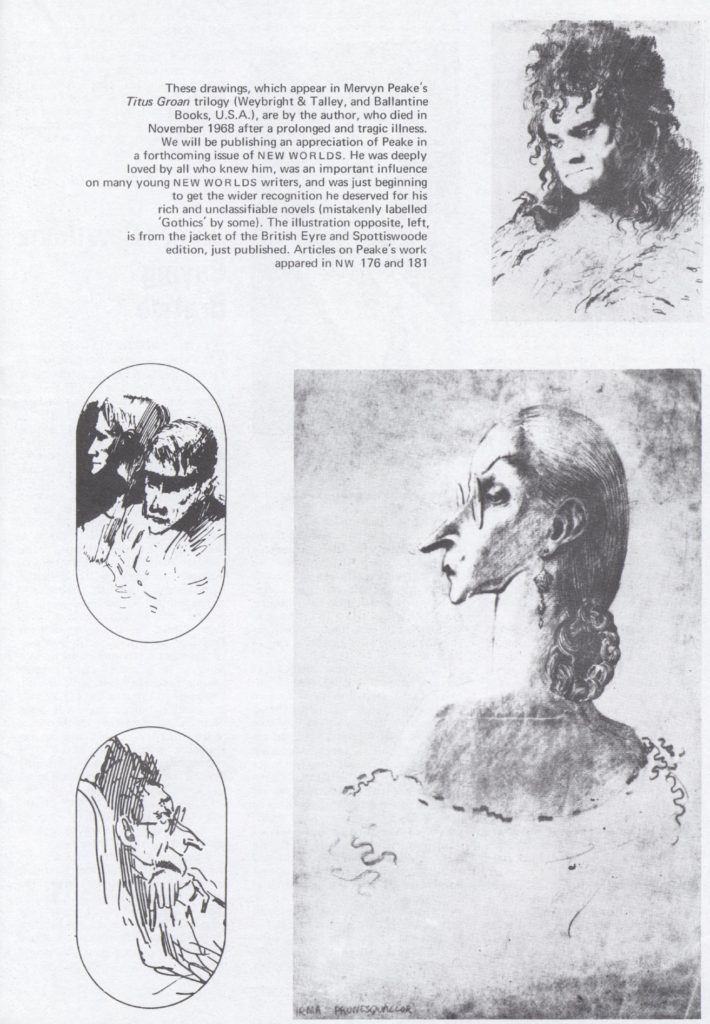

Just to be clear – New Worlds editors really like D. M. Thomas. As in, REALLY like. Declaring the poet to be “without question, one of England’s very best poets” in the Lead In, they like this particular poem so much it is available as a poster, courtesy of Charles Platt.

Just to be clear – New Worlds editors really like D. M. Thomas. As in, REALLY like. Declaring the poet to be “without question, one of England’s very best poets” in the Lead In, they like this particular poem so much it is available as a poster, courtesy of Charles Platt.

On a more positive note, have a great Christmas, and I look forward to returning next year when (hopefully) I will be less grumpy. “Bah, Humbug!” and so forth.

On a more positive note, have a great Christmas, and I look forward to returning next year when (hopefully) I will be less grumpy. “Bah, Humbug!” and so forth.

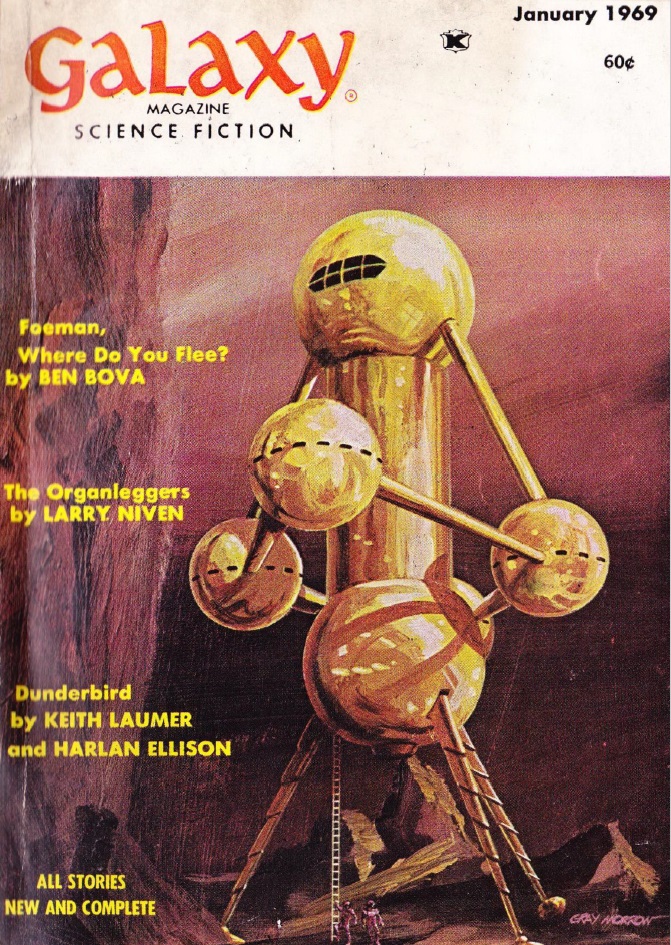

![[December 10, 1968] Back and forth (January 1969 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/681210cover-671x372.jpg)

![[October 12, 1968] (October 1968 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/681012covers-672x372.jpg)

![[September 18, 1968] Dangerous Visions (Not Those Dangerous Visions!) (September 1968 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/680920books-672x372.jpg)

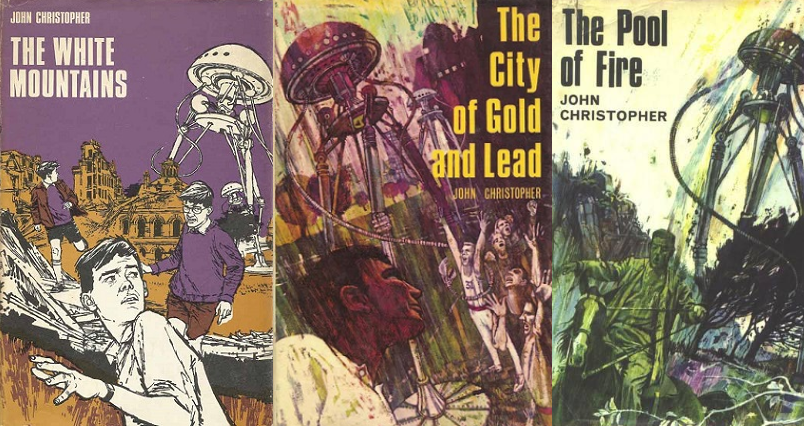

![[April 16, 1968] Tripods and Others (April 1968 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/680416covers-672x372.jpg)

![[March 2, 1968] Rules and Regulations (April 1968 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/IF-1968-04-Cover-639x372.jpg)

The stars of the show. (l.) Jean-Claude Killy sporting his medals. (r.) Peggy Fleming in her spectacular performance.

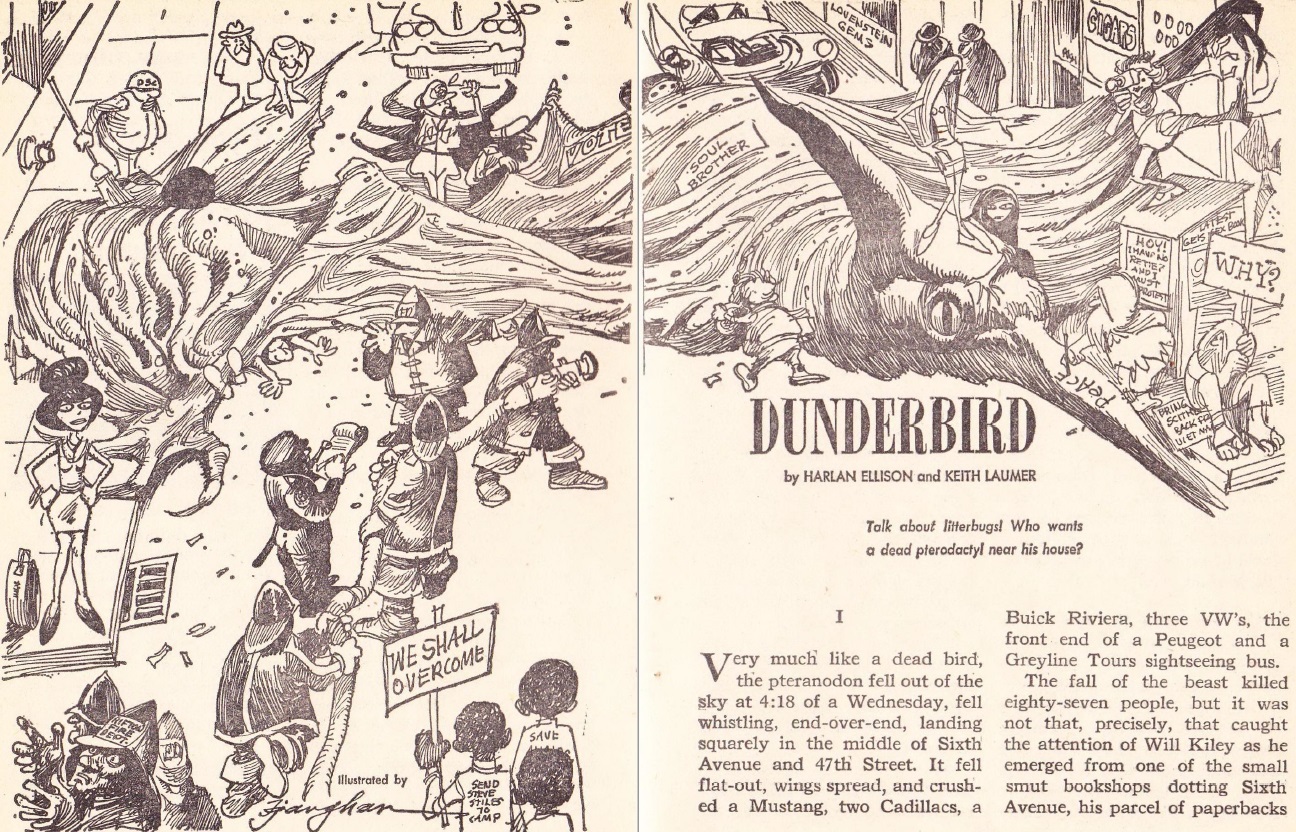

The stars of the show. (l.) Jean-Claude Killy sporting his medals. (r.) Peggy Fleming in her spectacular performance. The Advanced Guard prepare to study the fauna of Chryseis. Art by Vaughn Bodé

The Advanced Guard prepare to study the fauna of Chryseis. Art by Vaughn Bodé![[December 16, 1967] Long Distance Travel (December 1967 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/671216covers-672x372.jpg)

![[December 4, 1967] Devaluation (<i>New Writings in SF-11</i> & <i>Beyond Infinity</i> December 1967)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Cover-Image-672x372.jpg)

![[November 26, 1967] The Shock of the New – Part 3 <i>New Worlds</i>, December 1967 – January 1968](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/new-worlds-dec-67-672x372.jpg)

Carnaby Street, London: where's the snow?

Carnaby Street, London: where's the snow?

Cover by Eduardo Paolozzi, designed by Charles Platt and Christopher Finch

Cover by Eduardo Paolozzi, designed by Charles Platt and Christopher Finch Example of one of the pages of Eduardo Paolozzi and Richard Hamilton art.

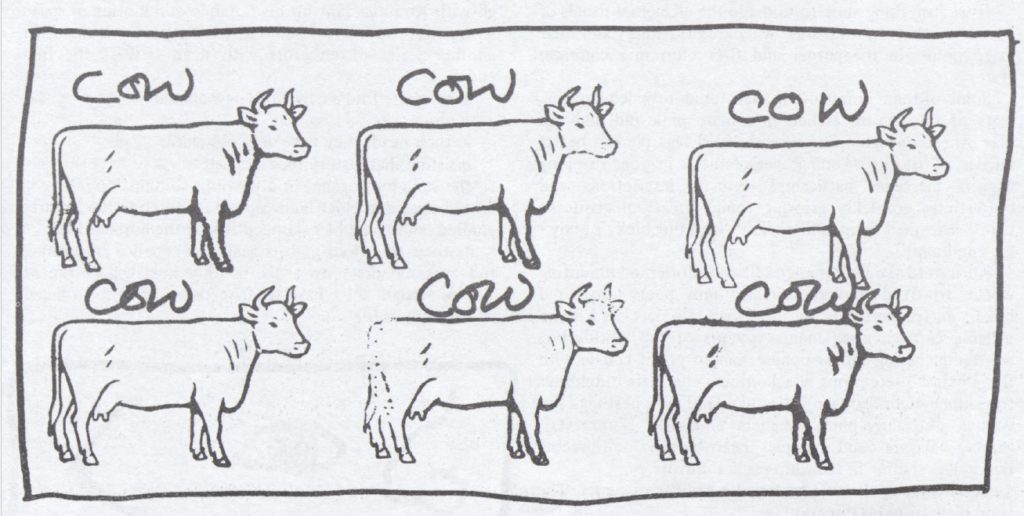

Example of one of the pages of Eduardo Paolozzi and Richard Hamilton art.

There's quite a few missing here!

There's quite a few missing here!