by David Levinson

A different civil rights struggle

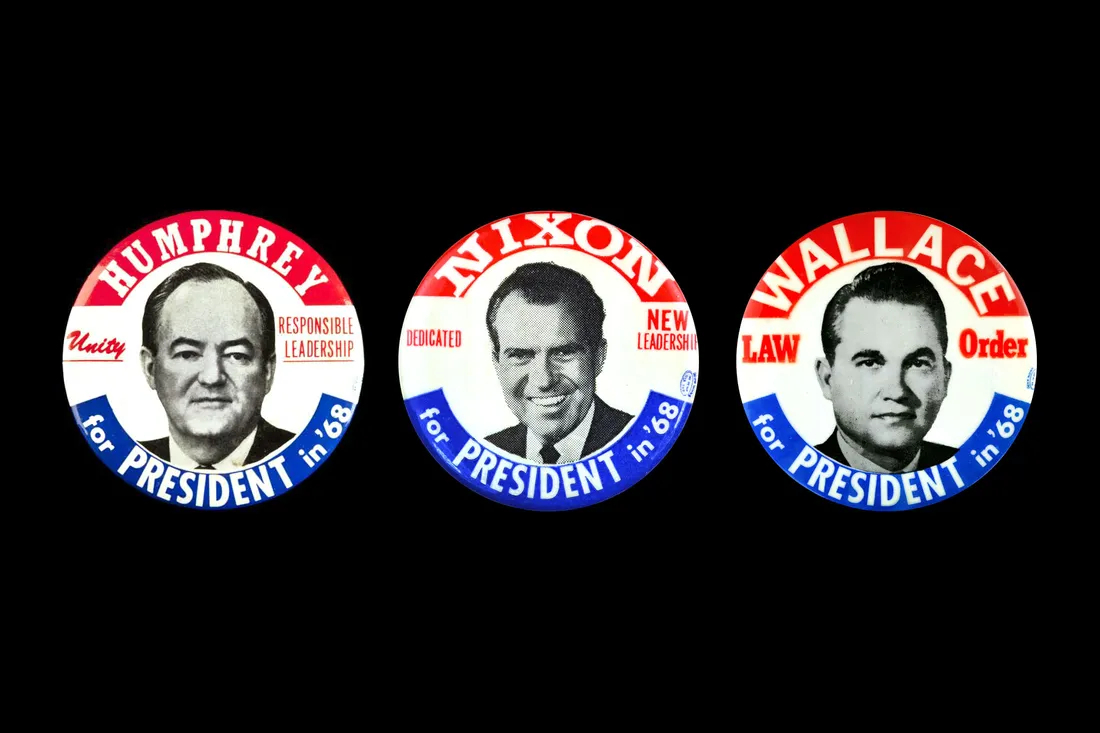

When Ireland gained independence in 1922, six predominantly Protestant counties in the north of the island opted to remain part of the United Kingdom, forming what is today known as Northern Ireland. In the almost 50 years since the partition, there have been tensions both between the two parts and within Northern Ireland between those who want a unified Ireland—predominantly Irish Catholics—and those who prefer the status quo: predominantly Protestants whose ancestors emigrated from Scotland. There have been riots and armed attacks over the decades, but the last few years have been relatively peaceful.

Irish Catholics in the north face discrimination in housing and employment, their political power is diluted by carefully drawn electoral districts, and they are grossly underrepresented in the police, which are backed by Protestant paramilitary units. In the last few years, a civil rights campaign has developed in an effort to right these wrongs. The first of several civil rights marches took place last August. In October, a march took place in Londonderry (called by its older name of Derry by the Irish) despite being denied permission. Television cameras caught images of police attacking the peaceful marchers, sparking outrage around the world.

Spurred by those images, a group of students at Queen’s University in Belfast formed People’s Democracy. On New Year’s Day, they began a march from Belfast to Derry, in imitation of Dr. King’s Selma to Montgomery marches. Along the way, they were met by counter-protests and occasionally attacked. On the 4th, as they approached a bridge in the village of Burntollet a few miles outside Derry, they were attacked by 200-300 Ulster Loyalists (a group not unlike the Citizens’ Councils in the American South) wielding stones, iron bars, and sticks spiked with nails. Meanwhile, the police stood by and did nothing.

Counter-protesters armed with sticks and iron bars attack civil rights marchers while the police look on

Counter-protesters armed with sticks and iron bars attack civil rights marchers while the police look on

That evening, the police stormed into the Bogside neighborhood, attacking Catholics in and outside their homes. Residents forced the police out and set up barricades. Police were denied any access to “Free Derry,” as it came to be known, for nearly a week. Eventually, the barricades came down and police patrols resumed, but tensions remain high.

At this point, a political solution seems unlikely, certainly not one from the Parliament of Northern Ireland. Proposals thus far have been not enough for the nationalists and too much for the loyalists.

A winning issue

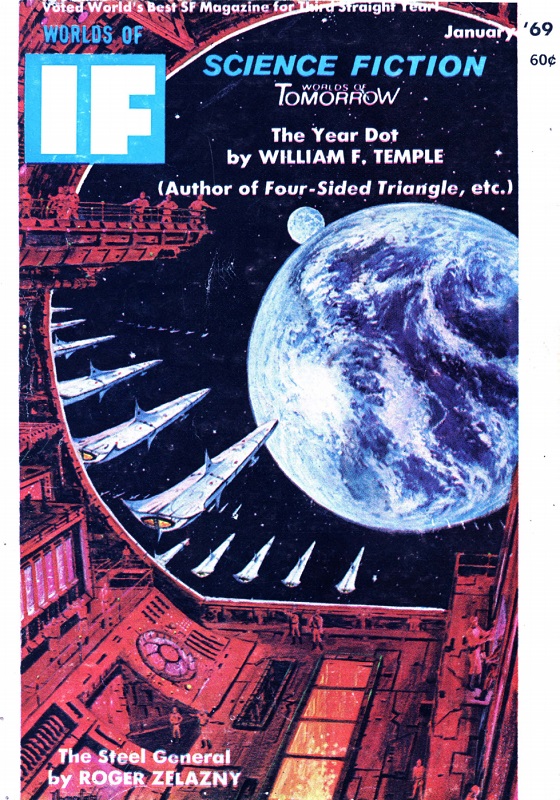

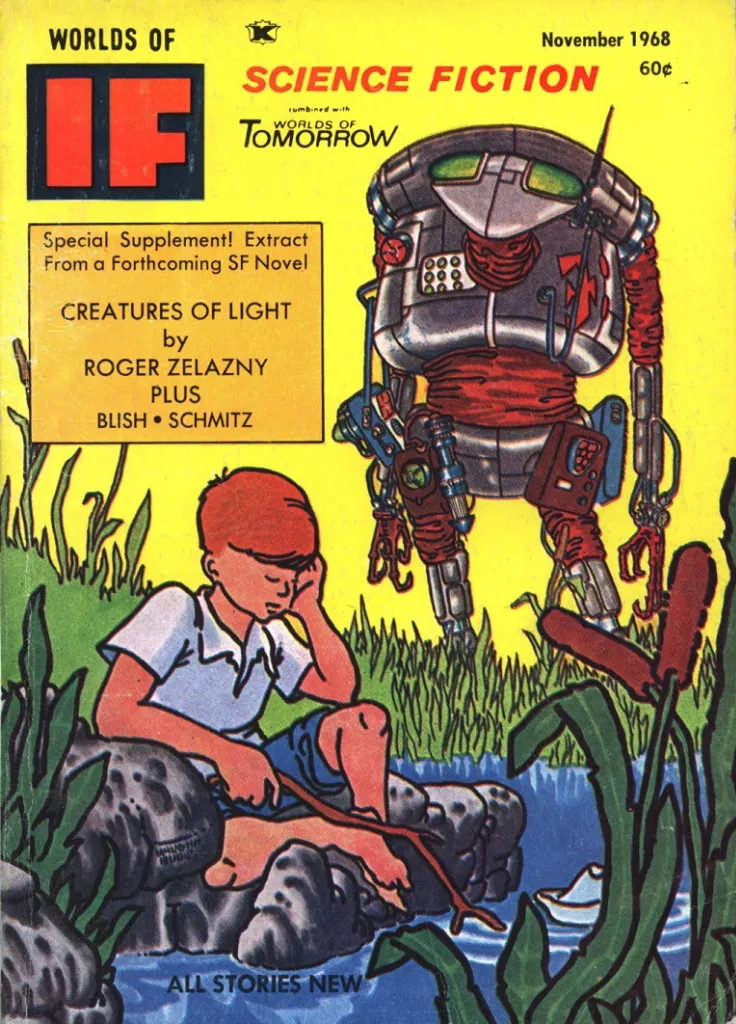

At the 1966 Worldcon, IF won the Hugo for Best Professional Magazine. To celebrate, editor Fred Pohl trumpeted a Hugo winner’s issue. He didn’t quite succeed; Frank Herbert wasn’t able to contribute due to a health issue, and the whole thing was weighed down by an installment of a not very good Algis Budrys serial. IF won again the next year, but there was no comparable issue. Last year, the magazine took its third straight best prozine Hugo, and Fred decided to try again. This time, he got every winner to contribute, and I do mean every. Even the winners in the fan categories are here. Let’s see how it all stacks up.

The Steel General rides again. Art by Best Professional Artist Jack Gaughan

The Steel General rides again. Art by Best Professional Artist Jack Gaughan

Down in the Black Gang, by Philip José Farmer

Mecca Mike is a member of the black gang, the engine crew for The Ship. (That’s an old term for the coal-engine stokers that now refers to the whole engine crew; the reason it applies to Mike might be a little different.) A shortage of hands means that he gets reassigned to Beverly Hills when a huge thrust potential is discovered there. If he can successfully develop that potential, there’s a promotion in it for him.

The thrust potential is in one of these apartments full of squabbling neighbors. Art by Gaughan

The thrust potential is in one of these apartments full of squabbling neighbors. Art by Gaughan

Farmer was co-winner in the Best Novella category for “Riders of the Purple Wage.” He’s dabbling in metaphysics again, which seems to be a favorite topic of his, but much better than he usually does. He even managed to bring the story to a successful ending, something he often has trouble with. Great ideas, incomplete execution, but not this time. This one’s right on the line between three and four stars, but I think I’ll be generous.

Four stars, but probably not a contender for the Galactic Stars.

Phoenix Land, by Harlan Ellison

Red is staggering through the desert on an expedition to find the risen ruins of an ancient civilization. He’s already buried his best friend and is now saddled with an ex-girlfriend and her husband, who financed the expedition. Unfortunately, he cut some corners. Whether or not they survive is an open question.

Harlan came away with two Hugos: Best Short Fiction for “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream” (which ran in the first Hugo winners issue I mentioned earlier) and Best Dramatic Presentation for “The City on the Edge of Forever” (which he’d probably rather not have). A lot of other winners and nominees also appeared in Dangerous Visions, which he edited. This particular story is full of that trademark Ellison anger, but the bite at the end doesn’t hit the way he wants it to.

A low three stars.

Authorgraphs: An Interview with Harlan Ellison

An interesting interview, but for a guy who can write tight, terse stories, he sure does like to run his mouth. Also, Harlan, my friend, you’re getting a little long in the tooth to be an enfant terrible.

Three stars.

Art by Gaughan

Art by Gaughan

The Ship Who Disappeared, by Anne McCaffrey

Best Novella co-winner Anne McCaffrey (for “Weyr Search”) brings us another story about Helva, who is essentially a brain in a box operating a ship that has become her body. This time she’s investigating the disappearance of other brain ships while also dealing with the realization she made a bad choice in her new partner.

Helva has a chat with the bad guy. Art by Brock

Helva has a chat with the bad guy. Art by Brock

Unfortunately, these stories have gotten progressively worse. They started from a very high mark, so they’re still readable, but this one barely makes the grade. Helva spends more time being unhappy about her choice of Brawn than she does worrying about disappearing ships. She succeeds mostly through coincidence and is unconscious for the key action.

Barely three stars.

The Frozen Summer, by David Redd

The centaur-like Senechi have colonized Earth, trapped in a new ice age. Looking for a quick score, two of them are investigating native legends of a valley where it is always summer, full of gold and gems, and guarded by a goddess. To the man she has held captive for centuries, she is simply “the witch.” Who, if any, will manage to escape?

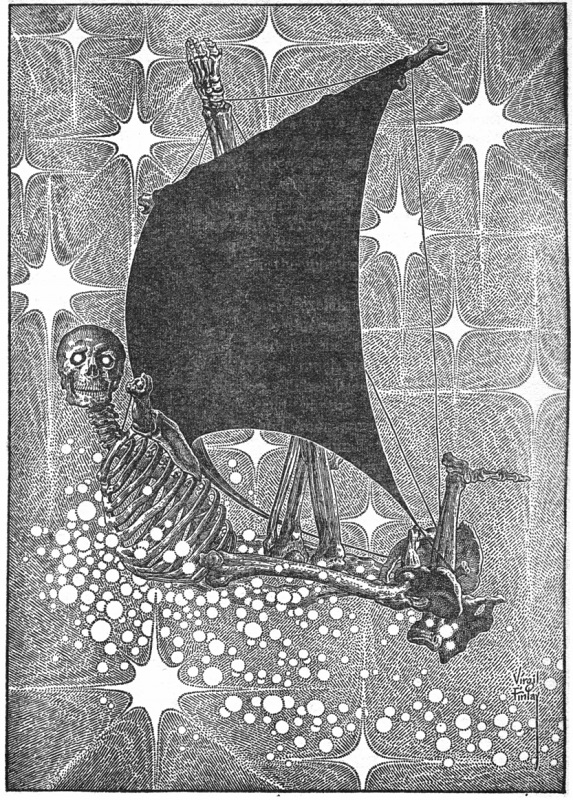

The witch turns the skeletons of those who invade her valley into golden ships. Art by Virgil Finlay

The witch turns the skeletons of those who invade her valley into golden ships. Art by Virgil Finlay

Redd is the only fiction author in this issue not to have won a Hugo. Powerful women in frozen landscapes seems to be a recurring theme with him, and all of his stories, on that theme or not, have a strange beauty to them. This one is no exception.

Four stars.

The Faithful Messenger, by George Scithers

George Scithers is the editor of Amra, which took home the Best Fanzine Hugo. Although he’s had stories printed in various fanzines over the years, this is his first professional sale, making him this month’s IF First author. As I understand it, Amra focuses on sword-and-sorcery tales; they carry a lot of critical articles on Conan and the like. Scithers’ story, on the other hand is more an old-fashioned SF tale of two human scouts encountering a robotic mailman on a distant planet. It’s well-told and nowhere near as hokey as it sounds.

Three stars.

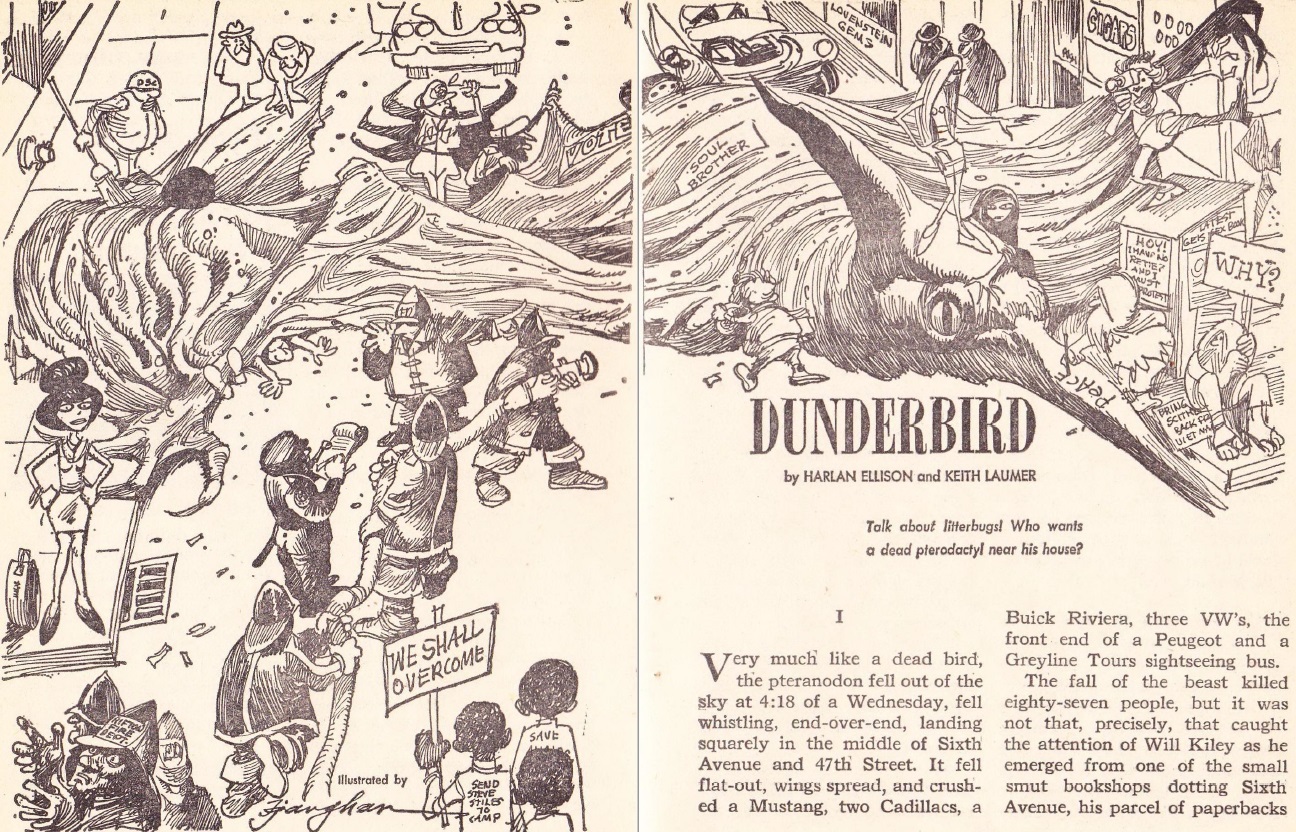

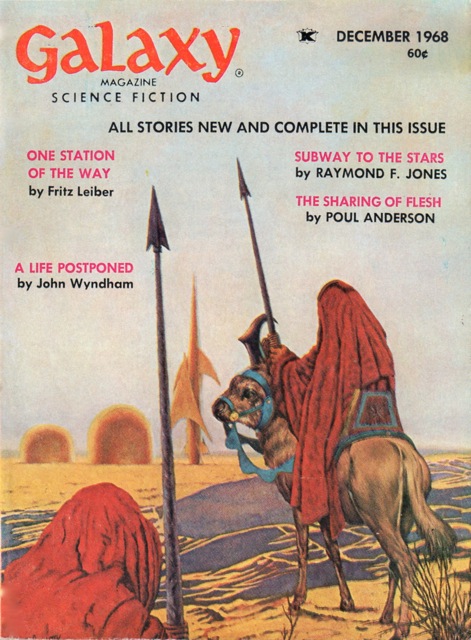

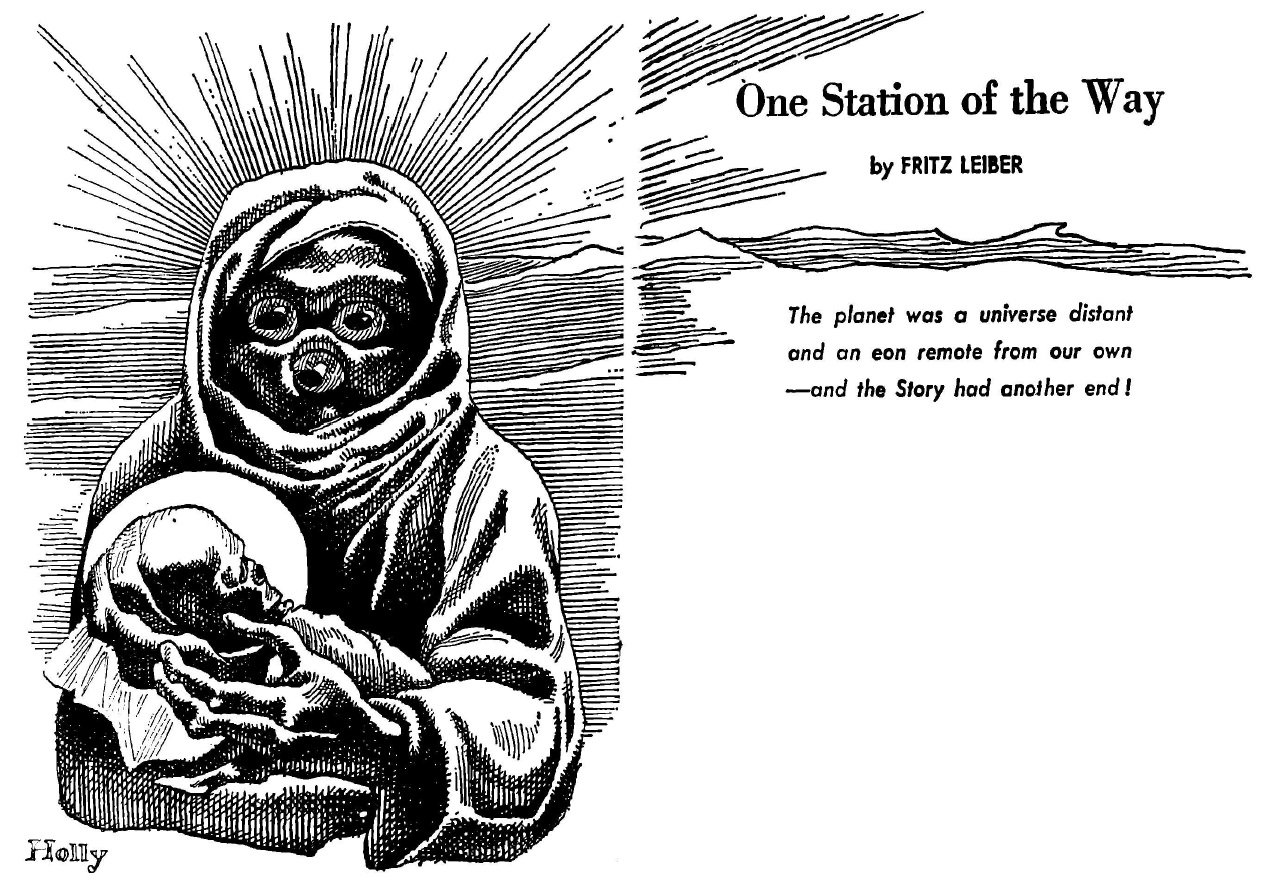

Endfray of the Ofay, by Fritz Leiber

Someone is diverting supplies intended for poor Blacks to the white reservations around North America, always with the message “Courtesy of the Endfray of the Ofay!” When these antics start to interfere in the war “between North America and Africa to Make the World Safe for Black Supremacy,” the Empress in Memphis (the one in Tennessee) demands something be done.

Her Serene Darkness is displeased. Art by Gaughan

Her Serene Darkness is displeased. Art by Gaughan

Fritz Leiber (Best Novelette for “Gonna Roll the Bones”) offers us another satire in the vein of A Specter is Haunting Texas. For me, this is much less successful. Most of the humor stems from the pun where Pig Latin and Black slang overlap, with very little elsewhere. I’m also not sure a white author should be poking into some of these corners. It’s often hard to tell if he’s mocking or perpetuating some stereotypes.

A low three stars.

If… and When, by Lester del Rey

Lester del Rey has never won a Hugo. Of course, he wrote most of his best stuff before the award existed. In any case, this month he looks at the differences between robots in the real world and in science fiction. Those in SF are much more mechanical men than machines. If we ever get machines that actually think, how might that differ from the way we do?

Three stars.

Saboteur, by Ted White

Mark Redwing has developed a method for manipulating public opinion and government policy through things like blackmail, riot, and assassination. It’s not entirely clear what his ultimate goal is. Nor is it clear just who the saboteur of the title might be.

Mark Redwing and his trusted assistant Linda. Art by Best Fan Artist George Barr

Mark Redwing and his trusted assistant Linda. Art by Best Fan Artist George Barr

Ted White won the Hugo for Best Fan Writer. Even filthy pros still write for the fanzines occasionally. This story is fully in pro mode, and it’s a good one. It should make you think and come back to you when you least expect it.

Four stars.

Creatures of Darkness, by Roger Zelazny

Zelazny (Best Novel for Lord of Light) wraps up the issue and his strange tale of Egyptian gods who are actually human beings in the far future. It’s impossible to say much about this convoluted story in the space available here, but it has that quintessential Zelazny-ness to it. It’s probably best read along with the other two bits, since characters have more than one name, and it’s sometimes hard to remember who is who. There are also clearly pieces missing from a larger whole. I look forward to seeing it all in one place.

Four stars, with the potential for five when it’s complete.

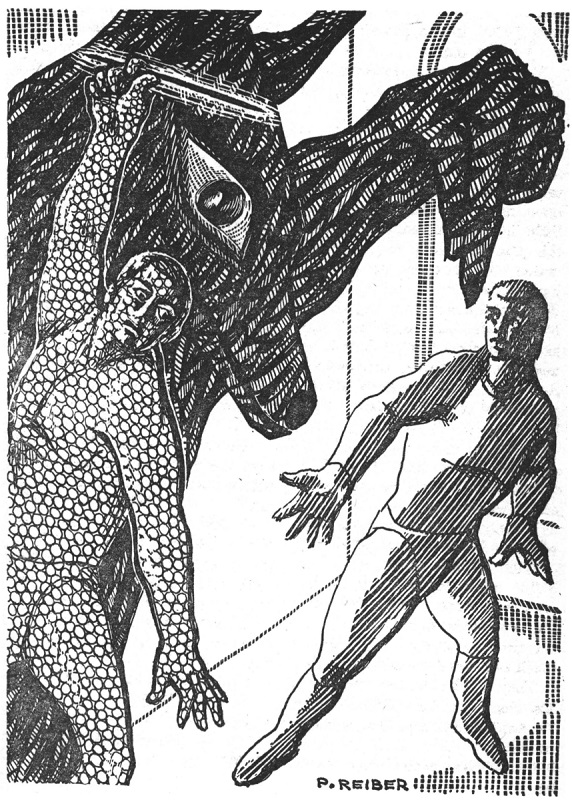

Osiris brings his greatest weapon to bear against Typhon. Art by Reiber

Osiris brings his greatest weapon to bear against Typhon. Art by Reiber

Summing up

There it is, a contribution from every single one of last year’s Hugo winners, fan and pro. One or two feel a bit dashed off or could have benefited from more time for another rewrite, but none are bad. On the whole, it’s a success. If every issue could be this good, IF would be guaranteed to walk off with a fourth Hugo this year in St. Louis.

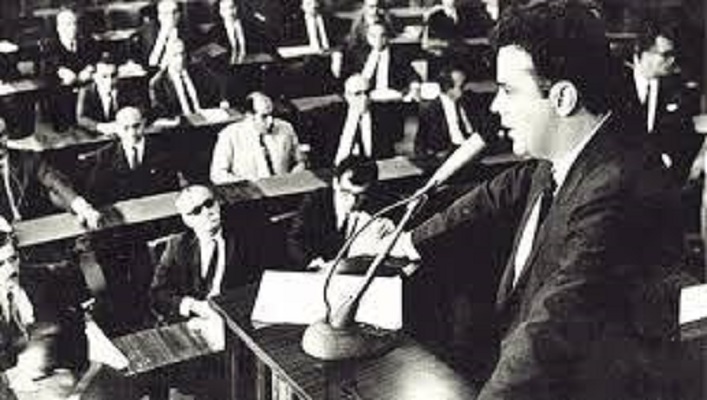

Has it been long enough since the last Retief story for a new one to feel fresh?

Has it been long enough since the last Retief story for a new one to feel fresh?

![[February 2, 1969] Winners and Losers (March 1969 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/IF-1969-03-Cover-574x372.jpg)

![[January 6, 1969] Booms and Busts (February 1969 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/690106cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 4, 1969] Not following through (February 1969 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/IF-1969-02-Cover-570x372.jpg)

The March of the One Hundred Thousand. The banner reads “Down with dictatorship. People in power.”

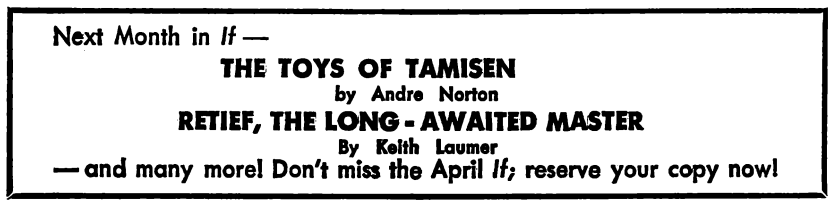

The March of the One Hundred Thousand. The banner reads “Down with dictatorship. People in power.” Márcio Moreira Alves delivering the speech that got him into trouble.

Márcio Moreira Alves delivering the speech that got him into trouble. Time travelers on their way to meet their ancestor. Art by Vaughn Bodé

Time travelers on their way to meet their ancestor. Art by Vaughn Bodé In desperation, Hatch tries to get his barge over the moving mountain. Art by Brock

In desperation, Hatch tries to get his barge over the moving mountain. Art by Brock How many of these folks can you identify? Art by Gaughan

How many of these folks can you identify? Art by Gaughan This isn’t happening in the world you might expect. Art by Gaughan

This isn’t happening in the world you might expect. Art by Gaughan A caricature, but recognizably Harry. Art by Rudy Cristiano

A caricature, but recognizably Harry. Art by Rudy Cristiano Rex and Venus discover an empty world. Art by Gaughan

Rex and Venus discover an empty world. Art by Gaughan Another Hugo winners issue. Dare we hope?

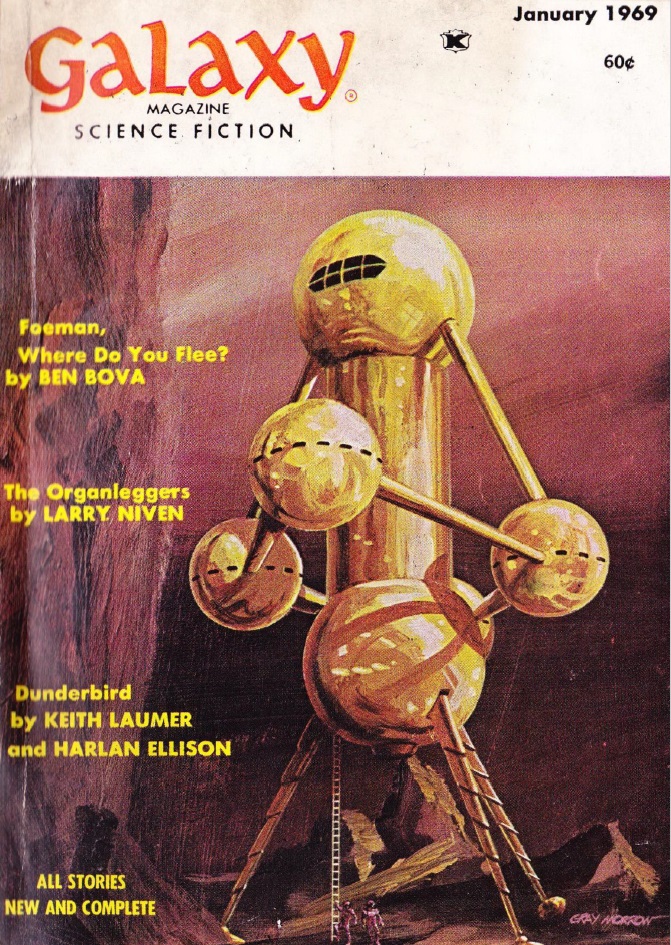

Another Hugo winners issue. Dare we hope?![[December 10, 1968] Back and forth (January 1969 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/681210cover-671x372.jpg)

![[December 2, 1968] Forget It (January 1969 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/1969-01-IF-cover-560x372.jpg)

Leonid Brezhnev after addressing the Soviet Central Committee earlier this year.

Leonid Brezhnev after addressing the Soviet Central Committee earlier this year. Just some random art not associated with any of the stories. Art by Chaffee

Just some random art not associated with any of the stories. Art by Chaffee Rex investigates the first portal. Art by Jack Gaughan

Rex investigates the first portal. Art by Jack Gaughan Doesn’t look like any of the X-Men I know. Beast maybe? Art by Brock

Doesn’t look like any of the X-Men I know. Beast maybe? Art by Brock Anubis doesn’t want Wakim to learn who he really is. Art by P. Reiber

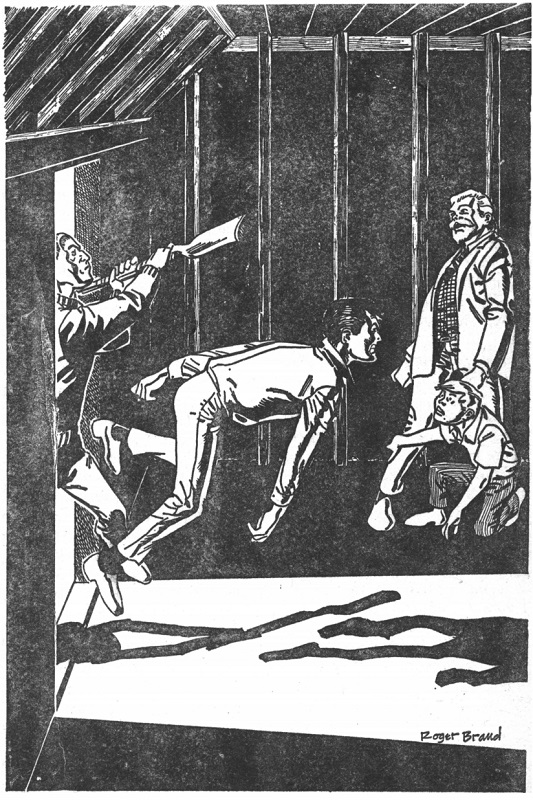

Anubis doesn’t want Wakim to learn who he really is. Art by P. Reiber Farris is imprisoned with his political nemesis. Art by Brand

Farris is imprisoned with his political nemesis. Art by Brand That was the look on my face at about this point in the story. Art by Reese

That was the look on my face at about this point in the story. Art by Reese I wonder if he’s always this dapper. Art by Gaughan

I wonder if he’s always this dapper. Art by Gaughan Can’t say anything here really excites me.

Can’t say anything here really excites me.![[November 20, 1968] Transitory and lasting pleasures (December 1968 <i>F&SF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/681120cover-672x372.jpg)

![[November 6, 1968] Who's the one? (December 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/681106cover-471x372.jpg)

![[November 2, 1968] Role Models (December 1968 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/IF-1968-12-Cover-672x372.jpg)

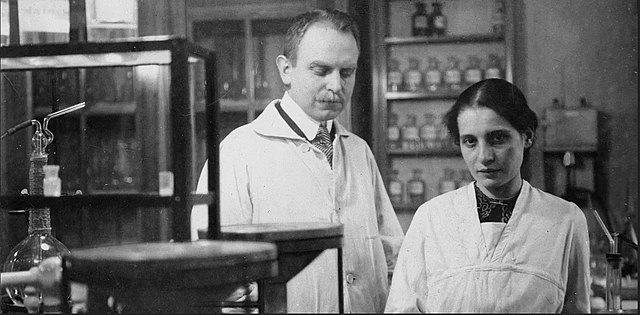

Otto Hahn and Lise Meitner circa 1912.

Otto Hahn and Lise Meitner circa 1912. Lise Meitner in 1963.

Lise Meitner in 1963. A previously unknown piece by the late Hannes Bok, probably the last new Bok cover ever.

A previously unknown piece by the late Hannes Bok, probably the last new Bok cover ever. He looks familiar. Art by Gaughan

He looks familiar. Art by Gaughan Whatever it is, it ain’t natural. Art by Wood

Whatever it is, it ain’t natural. Art by Wood Chief Wunnaara may be the only reliable person on the planet. Art by Virgil Finlay

Chief Wunnaara may be the only reliable person on the planet. Art by Virgil Finlay More action exactly like the action in Part 1. Art by Gaughan

More action exactly like the action in Part 1. Art by Gaughan There’s the Zelazny we were promised. This issue really needed it.

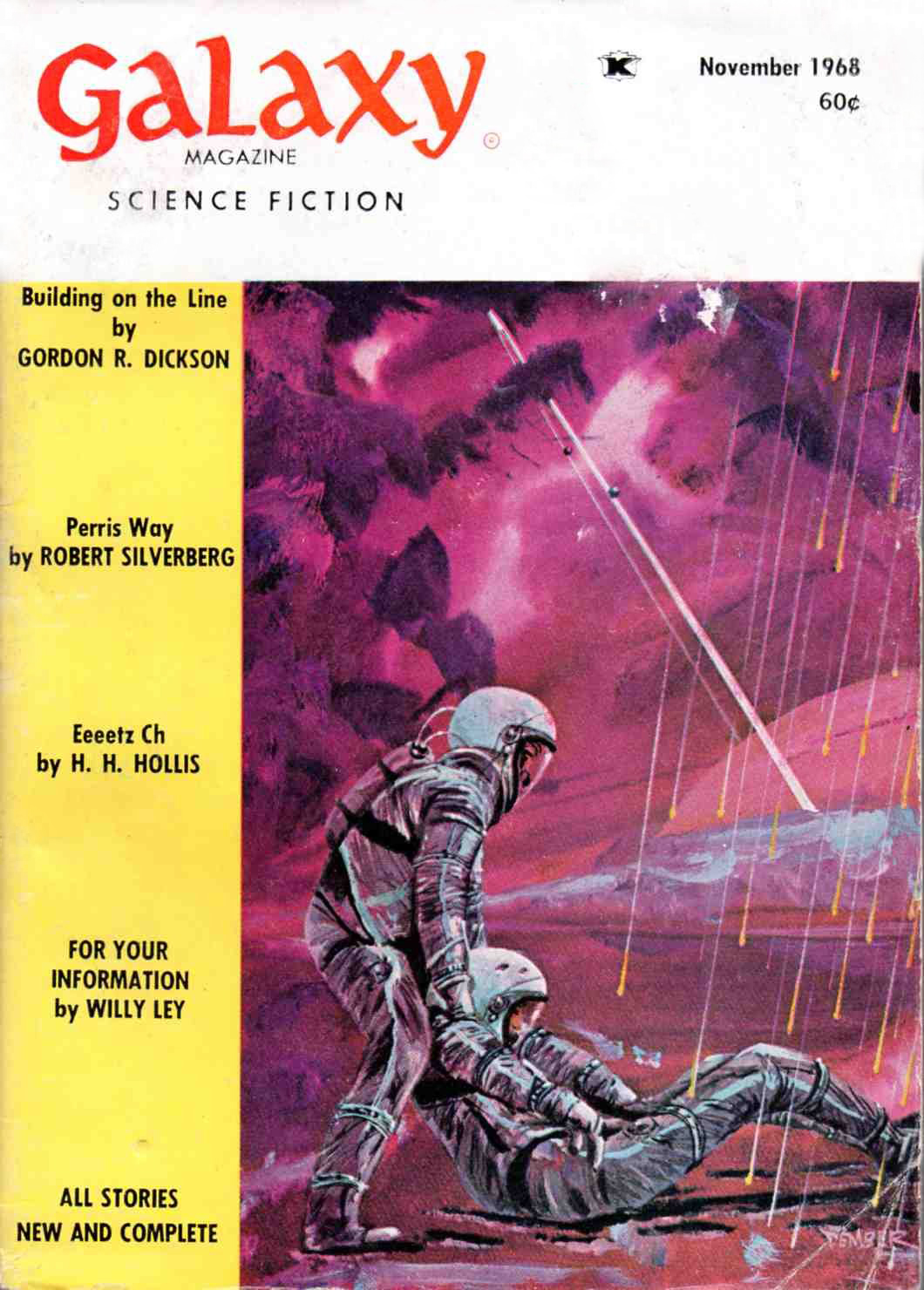

There’s the Zelazny we were promised. This issue really needed it.![[October 8, 1968] Probing the future (November 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/681008cover-672x372.jpg)

![[October 2, 1968] Future History Lessons (November 1968 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/IF-1968-11-Cover-672x372.jpg)

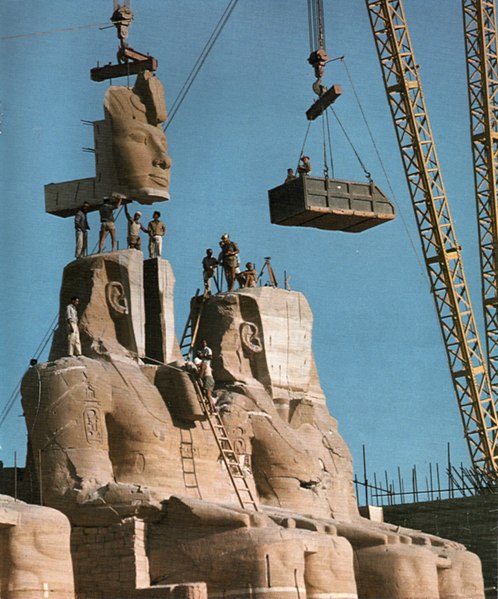

Ramses gets a face lift.

Ramses gets a face lift. The Waw is bored. Art by Vaughn Bodé

The Waw is bored. Art by Vaughn Bodé Action in the subway of abandoned Manhattan. Art by Gaughan

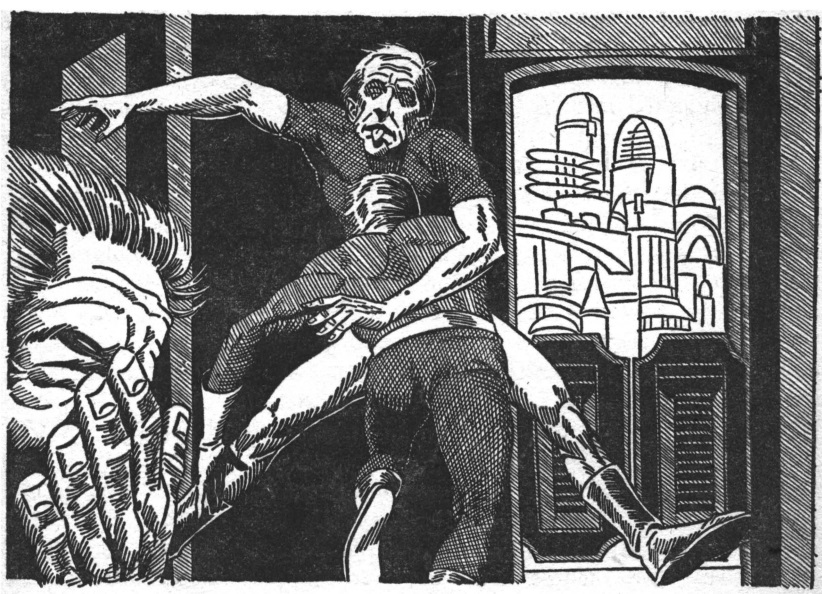

Action in the subway of abandoned Manhattan. Art by Gaughan Anubis and Osiris determine the fates of humanity. Art by P. Reiber

Anubis and Osiris determine the fates of humanity. Art by P. Reiber Art uncredited

Art uncredited Willis is presented with his new secretary. Art by Wallace Wood

Willis is presented with his new secretary. Art by Wallace Wood Science fiction from A(simov) to Z(elazny). That Zelazny piece might be another part of the new novel.

Science fiction from A(simov) to Z(elazny). That Zelazny piece might be another part of the new novel.