by David Levinson

Science fiction is generally considered to be literature that looks ahead. Much of Western culture also seems to be fairly obsessed with the miracles of progress and moving into a brighter future. Even communism, though less materially oriented, talks a good game about a better tomorrow. But there are also those who look to the past for better times, longing for the “good old days.” We can see the clash of these two world views in one form or another nearly every day in the newspapers. Perhaps the most obvious example can be seen in the Old South, where progress is resisted with fire hoses and police dogs. There, at least, we can hope that the moral arc of the universe is rather shorter than is its wont.

Looking Backwards

Details are still sketchy, but it appears that a coup was prevented last month in Bulgaria. Emboldened by the fall of Nikita Khrushchev and possibly influenced by the rhetoric of Mao Tse Tung, hardliners in the Bulgarian military and Communist Party denounced General-Secretary Todor Zhivkov for revisionism and opportunism due to his de-Stalinization of Bulgarian communism. Arrests between April 8th and 12th, as well as at least one suicide by a high-ranking general, seem to have prevented a major step back into the bad old days of Stalinism in Bulgaria. State-controlled media, of course, are denying the whole thing, but rumors abound.

Inside Baseball

On April 9th, the Houston Astros inaugurated their new stadium in an exhibition game against the Yankees. “Who?” you ask. For the last three seasons, they’ve been known as the Colt .45s. Now the sole owner, Judge Roy Hofheinz changed the name to the Astros to reflect Houston’s important role in America’s space program, and the new stadium will be called the Astrodome. What’s so noteworthy about all this? As you might have gathered from the name, the Astrodome has a roof. Over 700 feet in diameter, the dome consists a grid of semi-transparent panes of Lucite, and the field is covered with grass specially bred to be able to grow under the lower light conditions.

The Eighth Wonder of the World may be Texan hyperbole, but it is impressive

As any science fiction fan will tell you, innovations often produce unexpected consequences. That’s what half the stories in the field are about. As Victoria Silverwolf reported a couple of weeks ago, the problem in this case is that on bright, sunny days – and Houston has a lot of those – the glare from the roof panels and the grid of shadows caused by the support structure are causing players to lose routine fly balls. The decision has been made to paint the Lucite panes white, and a couple of sections have already been covered. The question now is if the grass will still get enough light to grow.

There was another experiment at the Astrodome that seems unlikely to be repeated. A catwalk structure hangs from the top of the dome. I don’t know how far above the field it is, but the peak of the dome is 208 feet above the playing surface. On April 28th, Mets radio broadcaster Lindsey Nelson was persuaded to call the game from the gondola. He was too scared to stand up until the seventh inning, getting the play-by-play via walkie-talkie from his producer. When he finally did get to his feet, he realized he couldn’t tell one player from another or a pop fly from a line drive. He refused to go up again, and it seems unlikely that anybody will follow in his footsteps. It might offer an interesting angle for a television camera, though.

Space Opera and Superscience

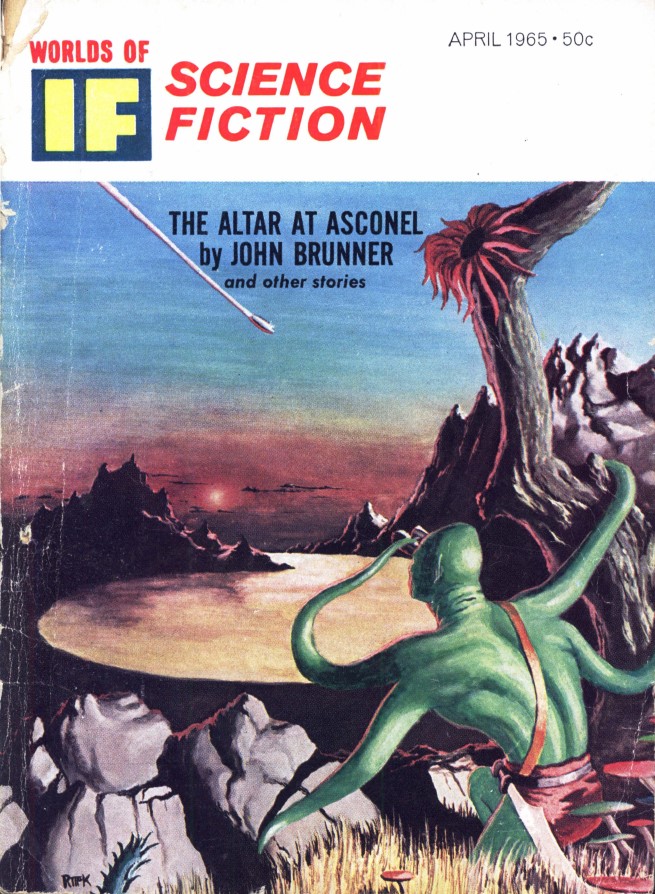

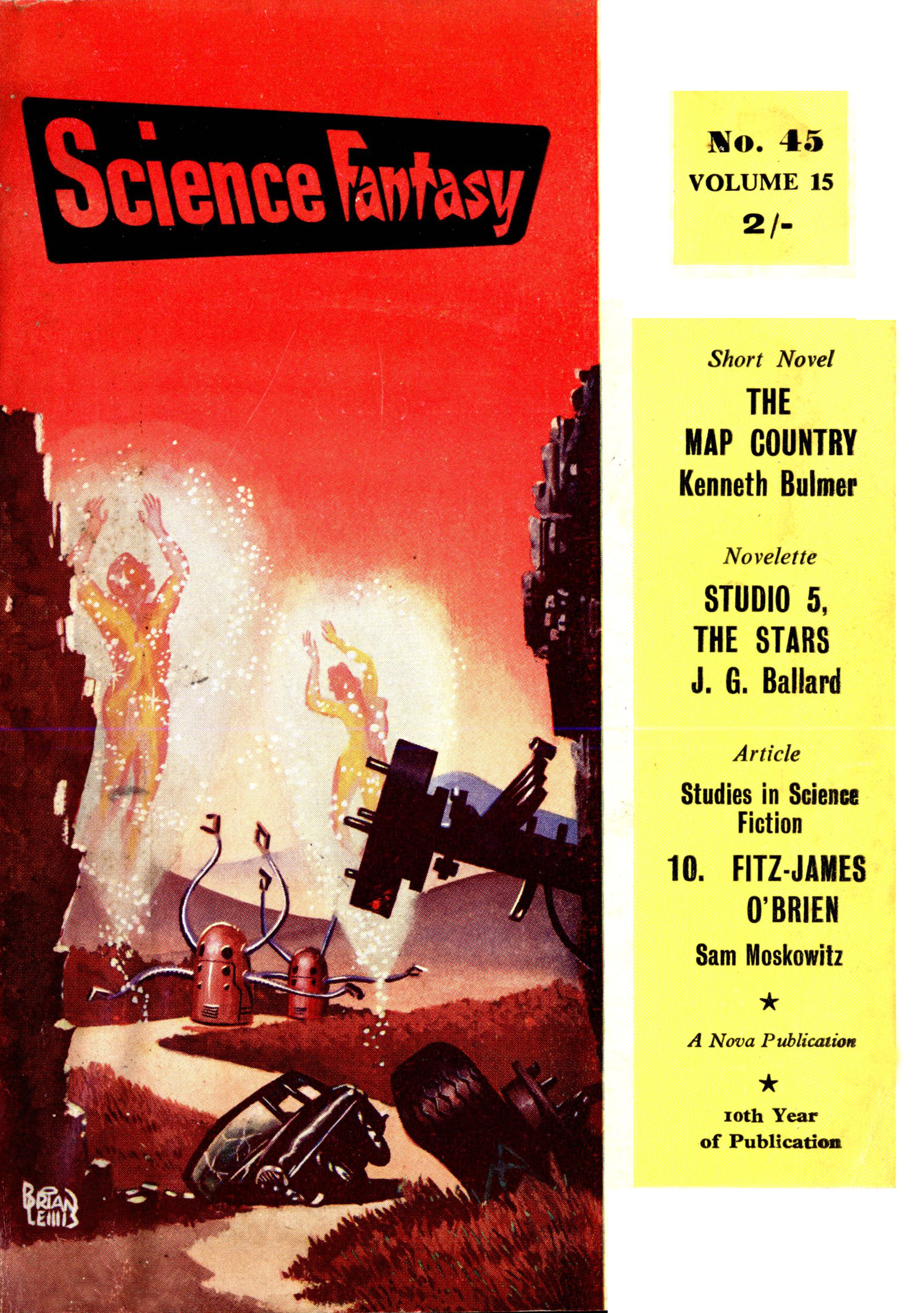

Lately, it has felt like science fiction has been doing a fair bit of looking back, too, what with the Edgar Rice Burroughs revival, Sprague de Camp putting Conan back in print, John Jakes’ Conan pastiche Brak, et cetera, et cetera, and so forth. The three magazines under Fred Pohl’s leadership, in particular, seem to have been on a real space opera kick for a while. This month’s IF is no exception.

This supposedly illustrates Skylark DuQuesne. If so, it’s not a scene in this month’s installment. Art by Pederson

Skylark DuQuesne (Part 1 of 5), by E. E. Smith, Ph. D.

Dick Seaton, hero of the previous three Skylark books, is enjoying an evening at home with his family, when they are interrupted by the thought-projected simulacra of the ablest thinkers of the galaxy. It seems that the clever ploy which he used to imprison the evil thought entities and the disembodied mind of the villainous Dr. Marc C. “Blackie” DuQuesne at the end of Skylark of Valeron is doomed to imminent failure. Seaton’s partner Mart Crane is brought in, and a plan is hatched in which a thought message is sent out, which can only be received by beings who are of good will can help in the situation.

The scene shifts to the home world of the “monstrous” Llurdi on the edge of the universe. The leaders are discussing Project University, in which the best minds of their human slaves the Jelmi are given everything they could need or want in the hopes that they will produce new technologies for the Llurdi. The proceedings are interrupted by a suicide attack by 30 Jelmi attempting to give their fellows the opportunity to escape. They fail. No one is even killed on either side. Supremely logical, the Llurdi pack the revolting Jelmi into a spaceship and allow them to “escape”.

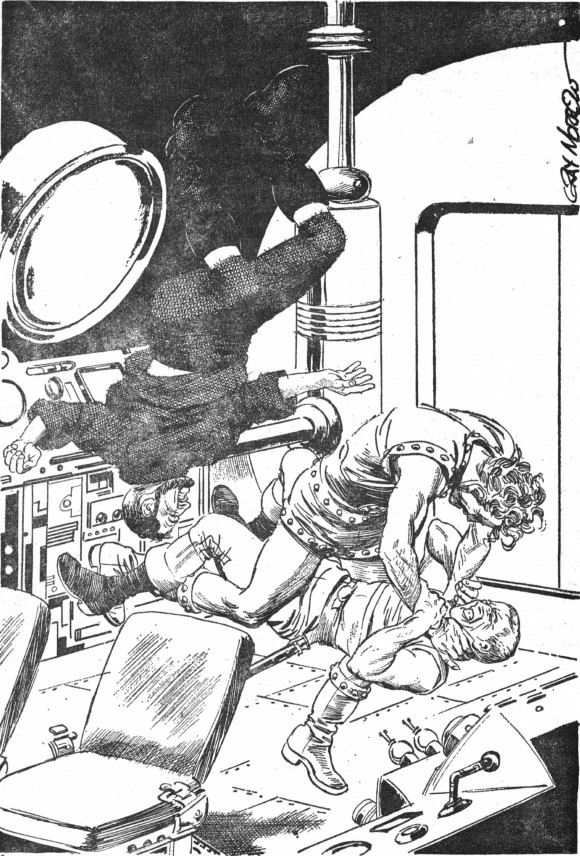

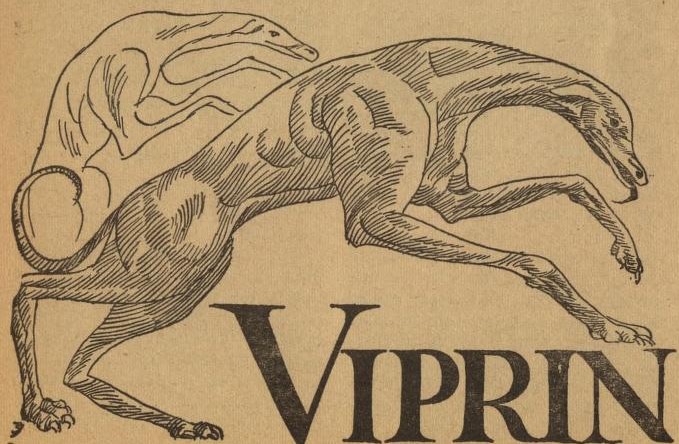

The Jelmi (background) confront their oppressors, the Llurdi. Art by Gray Morrow

Aboard the ship, the Jelmi deduce that they are being tracked, and that the Llurdi will give them free rein for a couple of generations, then swoop in, re-enslave their descendants and gather up anything new that’s been invented. They decide to seek out a world with sufficient sixth-order (I believe that means thought energy) forces to screen them from Llurdi scanning. The planet they choose: Earth.

Next, the scene jumps to a previously unknown Fenachrone fleet. The Fenachrone were the bad guys of Skylark Three, and Dick Seaton vaporized their home world at the end of that book. In Skylark of Valeron, Seaton learns of a secret colony ship, which he then hunts down and destroys. Now we find out that there’s yet another secret fleet composed of the evilest evil-doers of an evil people. In any case, the Fenachrone stumble upon a system containing two inhabited planets, one Llurdi and one Jelmi, whereupon the Fenachrone leader orders the vaporization of those two worlds. This draws the attention of the Llurdi, who proceed to destroy 16 of the 17 Fenachrone ships and capture the flagship.

Cut lastly to the ship containing the disembodied minds mentioned earlier. They have decided that Blackie DuQuesne doesn’t have what it takes to be one of them. They set him up with a ship capable of getting him to Earth and stick him back into his body. After a brief interlude in which the Seatons and the Cranes (both with infant children) as well as Crane’s former manservant Shiro and his new wife Lotus Blossom board the Skylark of Valeron, we cut back to DuQuesne. He is somehow detected by the Llurdi, but manages to evade them with his powerful mind blocks. Realizing how formidable the Llurdi are, DuQuesne sends out a call to Dick Seaton. To be continued.

Disclaimer: I do not care for the works of Doc Smith. I tried rereading the original Skylark five or six years ago, and flung it across the room in disgust about a quarter of the way through. On the other hand, I did rather enjoy The Imperial Stars last year, so I tried to approach this with an open mind.

When an English teacher, a critic, or even an author who has written what is very obviously science fiction condemns the genre with a wave of the hand, this is the kind of stuff they’re talking about. At best, it’s the genre’s juvenilia and is utterly unrepresentative of what science fiction is today. Line by line, there is some decent writing here. The opening paragraph is lovely. Too bad nothing that follows is worthy of it.

But my biggest problem is with the main protagonist. Firstly, Dick Seaton is racist. He would no doubt be shocked by this statement and point out that some of his best friends are green. I don’t mean he’d be likely to burn a cross on anyone’s lawn or join the Friends of Bull Connor, but the casual ease with which he tosses out phrases like “a Chinaman’s chance” or “If that’s true, then I’m a Digger Indian” (and what do you want to bet that phrase was cleaned up for publication) say a lot about how he views fellow humans who aren’t quite like him. Secondly and more importantly, Dick Seaton is a war criminal. He turned the Fenachrone world into a ball of expanding incandescent gas, and when he found out there were survivors, he hunted them down and killed them, too. When the Fenachrone leader destroyed those two worlds, we’re told he did it without remorse. If Seaton felt a twinge of remorse, that doesn’t make what he did any better.

Anyway, it’s hard to judge this as a whole, since the whole thing is really Smith just setting up the pieces, but it’s pretty bad. A low two stars, just because of that opening paragraph and the fact that I was able to get through the whole thing without too much effort. Even if you’re overcome with nostalgia, I doubt it could get all the way to three.

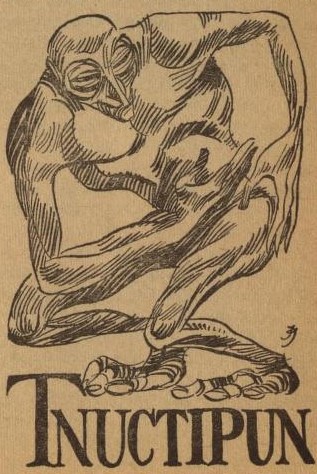

Simon Says, by Lawrence S. Todd

Lieutenant Nestil Lagotilom, an eight-foot tall reptilian (it’s not clear if he’s a mutant or an alien), is a member of the Terran armed forces, serving in a war against the Birds. Thanks to his brilliant tactical mind, he’s been ordered to take part in an experimental operation involving a new device called SIMO (Subelectronic Integrator for the Manipulation of Objects). Contrary to what it sounds like, it’s not a robot arm, but rather a device that will allow Nestil’s mind to be imprinted on some 2,000 Terran soldiers, and, once the action is over, all their experiences will be pumped back into his head so he can write a detailed after-action report. Thanks to a series of mishaps, Nestil’s consciousness winds up imprinted not only on the Terran troops, but the Birds and the local natives who aren’t happy about either group being there. Chaos ensues.

Lt. Nestil about to have his consciousness expanded. Art by Giunta

We go from the man who’s been at the science fiction game the longest to the newest. Larry Todd is this month’s IF first, though he’s not a complete newcomer. He’s had a few cartoons published, mostly in the late Imagination, but this is his first story. It shows. It rambles a bit, and the tone is a little too light for some of the things that happen. Even so, it was decent up to the final paragraph, where the author wrecked the whole thing by explicitly comparing events to the game Simon Says, and Nestil saying that he used to rig the game as a child (how does that work when you aren’t Simon?). He’s telling, not showing. Fix that and drop the “N” from the title and it’s a good story. As it is, a high two stars.

High G, by Christopher Anvil

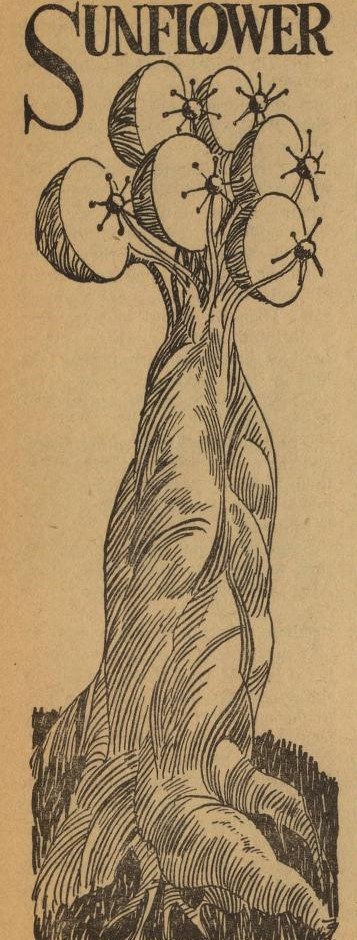

James Heyden, head of the Advanced Research Projects Division at the Continental Multitechnikon Corporation, has just received a memo from his boss telling him to cut back on projects that might interest the government and focus on science kits for kids. Congress isn’t willing to pay for anything revolutionary at the moment. This is part of a fairly regular pendulum swing on his boss’s part between gung-ho government research and piddling commercial stuff. Makes it hard to keep good research engineers working for the company. Just then, one of his engineers comes in with a working anti-gravity device. Throwing caution to the winds, Heyden decides that the only way to convince his boss and a stingy Congress that this thing needs to be built is for him and his engineers to fly to the Moon. Through massive misappropriation of company funds and tons of overtime, the race is on to get to the Moon before the boss gets back from a company trip.

Engineers call something cobbled together like this spaceship a “kluge.” Art by Gaughan

Christopher Anvil tends to be a very uneven writer, sometimes up, sometimes down. This one is right in the middle of his range. Sadly, he tends to be down a little more often than he’s up. For the second month in a row, I find myself wondering why a story is here rather than in Analog. Anvil often writes for Campbell, and this one is right up the editor’s alley: stupid bureaucrats stupidly getting in the way of progress. It might have fared better there, but here it’s too long and filled with pointless minutiae. Do we really need to follow lengthy discussions about the pricing of those kiddie science kits? A high two stars.

The Followers, by Basil Wells

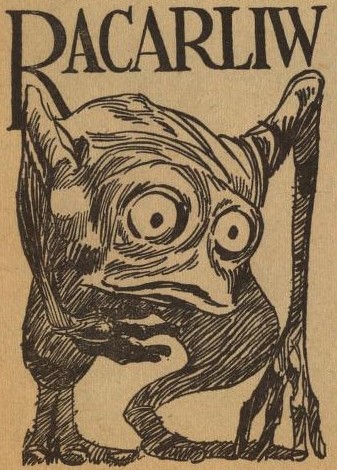

Balt Donner is part of the three-man crew of the exploration ship Avalon. Small, plain and timid in real life, his job calls for him to take mental control of a seven-foot tall robot covered in bronzed pseudoflesh. The ship is currently on the planet Hald, which is inhabited by a people who, though noseless and with elongated ears, are otherwise quite human. Each Halden has a twin, an oddly doglike, eight-limbed creature known as a Follower. The crew of the Avalon is trying to figure out the odd lifecycle of the planet which allows such disparate beings to be born from the same mother.

Their time in space is getting to the crew. Senior crewman Ernest Lytte fights off space madness with ever increasing doses of drugs, while Jeff Carney gets by with alcohol and forbidden carousing on planets with humanoid races. Up to now, Balt has managed to stay sane, but he has begun to fall for a native woman named Alno. She is an outcast, because her Follower died, and has fallen for Balt (in the form of the robot Cass), who appears to her to be an outcast as well. As the other crewmen squabble over procedure, Balt learns that Alno is going to be given a new Follower. Eventually, the biology of Hald is explained, and the ship lifts for the next stop on their long journey back to Earth.

This one is pretty good, though rather dark. Basil Wells has been cranking out stories in a variety of genres for a quarter century, and his prose style reflects that. It’s a little pedestrian, without being pulpy, but the story he tells here is neither. It’s much more in a modern mode, and an author more attuned to that mode – a Brunner or a Zelazny, say – could have turned this into a four, maybe a five star story. As it is, it’s a solid three stars and the best in the issue.

No Friend of Gree, by C. C. MacApp

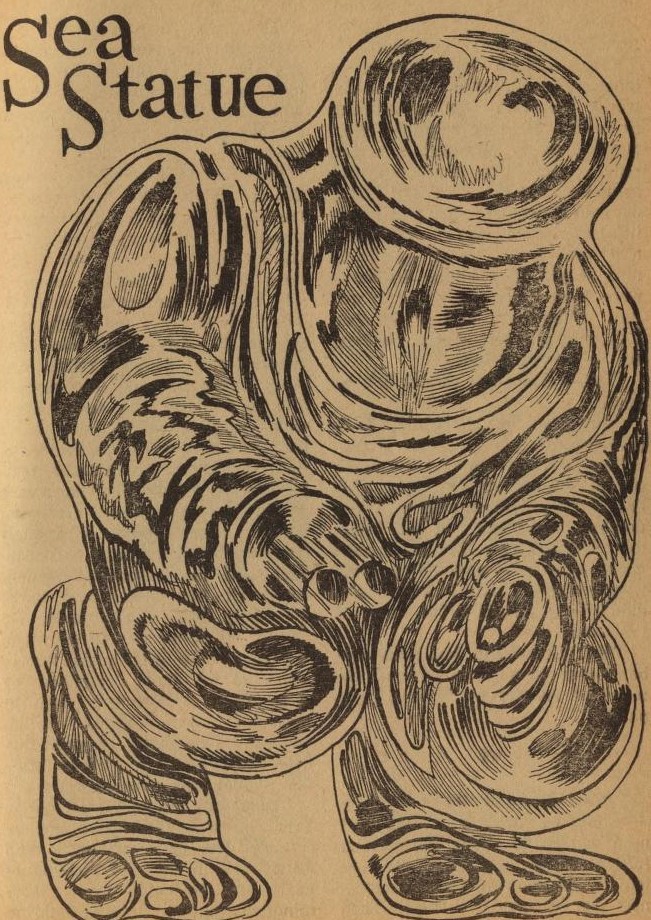

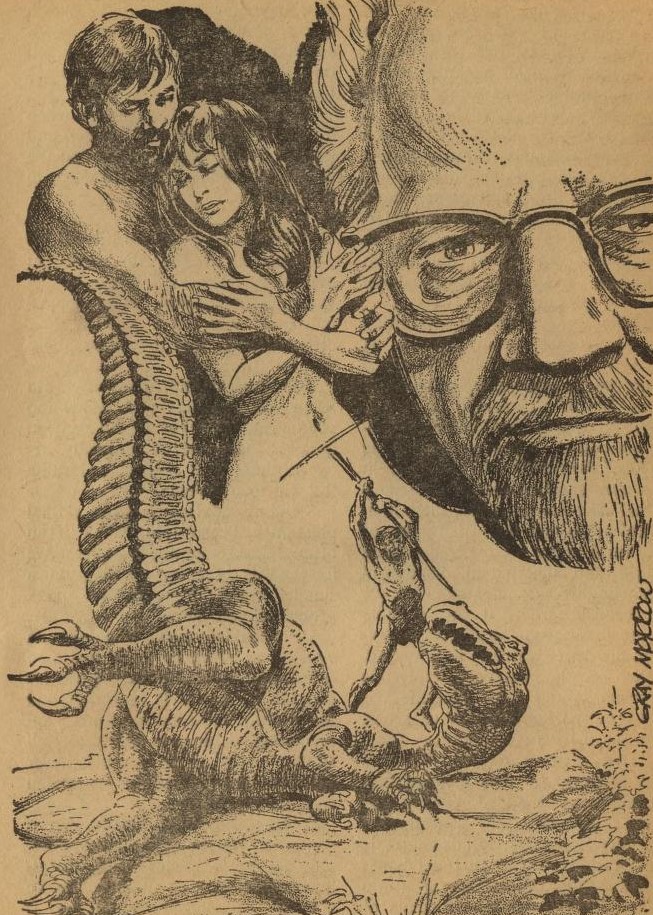

Steve Duke is trying to figure out why a Gree ship-of-the-line and a small exploration ship are in a backwater binary system. There is a single planet, Terrestrial in nature, but too close to the blue-white companion of the red giant. It is also tidally locked to the star it orbits, always showing one face to its star. There are no signs of technology, so when the Gree ships fire a salvo of missiles to sterilize the planet, Steve wants to know what’s going on. He diverts the missiles and produces enough fake evidence to convince the Gree ships that their mission is accomplished.

Once the Gree slaves leave, Steve lands with two B’lant crewmen to investigate. Searching the Gree camp, they find the hastily dug grave of a Gree slave and are interrupted by the arrival of a vaguely humanoid creature covered in mud and debris. The three of them go wandering across the world, struggling through dense grass that grows higher than their heads and encountering a variety of enormous insectoids. First, one B’lant goes missing and then the other. Eventually, the answers to the puzzles he’s found are revealed to Steve (through no doing of his own). Will he follow the Gree’s lead and sterilize the planet, or has he found a potential weapon for the war against the Gree?

Steve and one of the B’lant see something strange and disgusting. Art by Nodel

When I saw there was a Gree story in this issue, I made a bet with myself that Steve would go behind enemy lines and infiltrate a Gree base by pretending to be walking wounded. Rarely have I been so glad to lose a bet. This is a darn sight better than the previous two stories in this series, though not as good as the first. However, it could probably have been cut by a third. A lot of the difficult slog through the dense vegetation is, well, a difficult slog for the reader. Also, Steve continues to be little more than a cardboard cut-out of a character. A high two stars.

Summing Up

Returning to the beginning, science fiction is, ostensibly, the literature of tomorrow. (Of course, it’s really about today or, at most, later this afternoon, but I digress.) But as I noted above, we’re seeing a lot of revivals, rehashes and regressive pastiches. Fred Pohl, in particular, seems to be on something of a space opera kick of late. Don’t get me wrong. It’s certainly possible to tell a good, modern sort of story within the framework of space opera. Fred Saberhagen certainly pulls it off with his Berserker stories; John Brunner does it quite often (though not always); Roger Zelazny has turned out some beautiful work in the old planetary romance settings.

Most of the time, though, that’s not what Pohl is serving us. We’re getting stuff that could easily have appeared back before the War. Sometimes it seems like a problem story in the good, old Campbellian style is the most modern thing we can hope for. And now we’re going to be saddled with the great-granddaddy of them all for months (and don’t be fooled by that “Part 1 of 3” in the table of contents; a contact at Galaxy Publishing says to expect more like 5). Judging from the comments in the letter col, lots of readers have been eagerly awaiting this Doc Smith novel ever since Fred announced it a year or so ago. Maybe it’s a fit of nostalgia. After all, they say the Golden Age of science fiction is 12. But it’s a sad day when a professional baseball team is more forward-thinking that one of the leading science fiction magazines.

Van Vogt and Schmitz seems like an… odd pairing

Our last three Journey shows were a gas! You can watch the kinescope reruns here). You don't want to miss the next episode, May 9 at 1PM PDT, a special Arts and Entertainment edition featuring Arel Lucas, Cora Buhlert, Erica Frank…and Dr. Who producer, Verity Lambert! Register today and we'll make sure you don't forget.

![[May 2, 1965] FORWARD INTO THE PAST (June 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/IF-June-1965-cover-647x372.jpg)

![[March 16, 1965] Browsing the Stacks (May 1965 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v03n01_1965-05_0000-2-672x316.jpg)

![[March 8, 1965] An Alien Perspective (April 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/650308cover-435x372.jpg)

![[March 4, 1965] OLD WINE IN NEW BOTTLES (April 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/IF-march-cover-655x372.jpg)

![[February 26, 1965] Dare to be Mediocre (February Galactoscope #2)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/650226covers-655x372.jpg)

![[February 6, 1965] Too much of a… thing (March 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/650204cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 26, 1965] Down the Rabbit Hole…Again (February 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/650126cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 18, 1965] Doors also open (February 1965 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/650118cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 14, 1965] The Big Picture (March 1965 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v02n06_1965-03_0000-2-672x372.jpg)

![[January 6, 1965] Plus C'est La Même Chose (February 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/650106cover-518x372.jpg)