by Victoria Silverwolf

There's a new anthology of original science fiction and fantasy stories in bookstores this month. It's certain to be the topic of a lot of discussion among SF buffs, and maybe even some arguments.

It's also big; more than five hundred pages, and it'll set you back a whopping seven bucks. It's so big, in fact, that Galactic Journey is going to slice it into three pieces and discuss it in a trio of articles. (Why three? Because it's got thirty-three stories in it, and eleven articles would be silly.)

Let's dig into the first part of this mammoth collection and see if it's destined to be the Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band of speculative fiction, or just another dud.

Dangerous Visions, edited by Harlan Ellison

Wraparound cover art by the husband-and-wife team of Leo and Diane Dillon, who also provide an interior illustration for each story.

Before we get to the nitty-gritty of fiction, we've got no less than two forewords by Isaac Asimov and a lengthy introduction by the editor.

In The Second Revolution, the Good Doctor outlines the history of modern science fiction from Gernsback through Campbell, and into the New Wave. Astounding was the first revolution, you see, and now we're in the second one. That may be a little simplistic, but it gets the point across.

Harlan and I, on the other hand, is a personal essay about Asimov's relationship with the editor, ending with a teasing anecdote. Ellison adds a long footnote offering a different version of their first encounter.

More substantial is Thirty-Two Soothsayers, the editor's longwinded but endlessly entertaining and informative account of what this book is supposed to accomplish, and how it came to be. Ellison wanders all over the place in this piece, and it's a fun ride. In brief, the stories he chose are supposed to be both enjoyable and provocative, with new ideas that might not appear in the usual SF markets. We'll see.

(If you're wondering why thirty-two and not thirty-three, it's because one writer supplies two stories; but that's for another time.)

I should mention that each story comes with an introduction by the editor and an afterword by the author, except for the one case when those roles are reversed. You'll see what I mean in a while.

I'm going to do something a little different here. I'll rate the quality of each story with the usual one to five stars, but I'll also add an indication for how dangerous each one is. This will be determined by sexual content, violence, profanity, experimental narrative style, taboo subject matter, etc. GREEN = safe to proceed, YELLOW = caution indicated, RED = hazardous conditions.

Let's begin.

Evensong, by Lester del Rey

An unnamed character flees through the universe in an attempt to escape those who have overthrown his reign. To say anything else would give away the point of the story, which is an allegory.

Three stars. YELLOW for questioning the deeply held beliefs of some readers.

Flies, by Robert Silverberg

In a premise similar to his excellent novel Thorns, the author presents a severely injured astronaut who has been put back together by aliens. In this case, however, his body has been restored to normal, but his mind has been made more sensitive to the emotions of others. That doesn't work out well.

Silverberg has become a fine writer, one of the best now working. Like Thorns, this is an uncompromising look at human suffering.

Five stars. YELLOW for scenes of extreme cruelty.

The Day After the Day the Martians Came, by Frederik Pohl

Set in the very near future, this tale deals with humanity's reaction to the discovery of ugly, semi-intelligent lifeforms on the red planet. Mostly, people make nasty jokes about them. The intent of the story is to expose human prejudices, in a way that's about as subtle as a brick thrown through a window.

Three stars. YELLOW for dealing with a major social problem in the USA today.

Riders of the Purple Wage, by Philip Jose Farmer

This is, by far, the longest story in the book. It is also incredibly dense and fast-paced, so any attempt to describe the plot would be a miserable failure. That said, I'll just mention that it takes place in a very strange future, involves an artist and his tax-dodging ancestor, and contains a ton of wordplay. There are scenes of slapstick violence that are simultaneously hilarious and offensive. It's a wild rollercoaster ride, so keep your seatbelt tightly secured.

Five stars. RED for a Joycean narrative style and Rabelaisian humor.

The Malley System, by Miriam Allen deFord

In the future, the worst criminals receive a very unusual punishment. This is a grim story, that doesn't shy away from the horrors perpetuated by human monsters.

Three stars. YELLOW for violence.

A Toy for Juliette, by Robert Bloch

In a decadent future, a man uses the only time machine in existence to kidnap people from the past, in order to satisfy the whims of his sadistic granddaughter. He picks the wrong potential victim. This is a spine-chilling little science fiction horror story with a twist in its tail.

Three stars. YELLOW for sex, torture, and murder.

The Prowler in the City at the Edge of the World, by Harlan Ellison

This is a direct sequel to the previous story, with an introduction by Bloch and an afterword by Ellison. An infamous murderer finds himself in the far future, where the inhabitants enter his mind in order to enjoy his sensations as he kills.

Written in an experimental, almost cinematic style, this is an unrelenting look at the evil that lurks inside all of us. Not for weak stomachs.

Four stars. RED for explicit violence.

The Night That All Time Broke Out, by Brian W. Aldiss

People get so-called time gas supplied to their homes through pipes. It allows them to enjoy better times in the past. As with any form of technology, things can go wrong. This is a light comedy with a unique premise.

Three stars. GREEN for whimsy.

The Man Who Went to the Moon – Twice, by Howard Rodman

A young boy takes a trip to the Moon by holding on to a balloon, becoming a local celebrity. Many years later, as a very old man, his only claim to fame is not as valued as it once was. Reminiscent of Ray Bradbury, this is a gentle, quietly melancholy tale.

Three stars. GREEN for wistful nostalgia.

Faith of Our Fathers, by Philip K. Dick

The Communist East has won a hot war with the Capitalist West. The protagonist is a bureaucrat given the task to determine which of two term papers truly represents the Party line. Meanwhile, a seemingly harmless substance allows him to perceive what appear to be multiple and contradictory truths about the Mao-like Party leader.

That's a vague synopsis, because this is one of the author's stories in which you've never quite sure what is real and what is illusory. Ellison strongly hints that it was written under the influence of hallucinatory drugs. Be that as it may, it's a provocative and disturbing look at the possible nature of reality.

Four stars. YELLOW for politics, drug use, and existential terror.

The Jigsaw Man, by Larry Niven

A man is sentenced to death for his crime. His organs will be harvested for transplant. Through a series of unusual circumstances, he manages to escape from prison, but his troubles aren't over yet.

The full impact of this story doesn't hit the reader until the very end, when we find out the nature of the man's offense. Other than that, it's an ordinary enough science fiction action/suspense story.

Three stars. GREEN for futuristic adventure.

One Down, Two To Go

So far, this is a fine collection of stories, without a bad one in the bunch. Sensitive readers might want to stay away from the more dangerous ones, but most mature SF fans will enjoy it.

</small

</small

Dr. Barnard (I.) and Philip Blaiberg (r.), probably before the surgery.

Dr. Barnard (I.) and Philip Blaiberg (r.), probably before the surgery. Dr. Shumway at a press conference last fall (l.), Mike Kasperak and his wife, Ferne (r.)

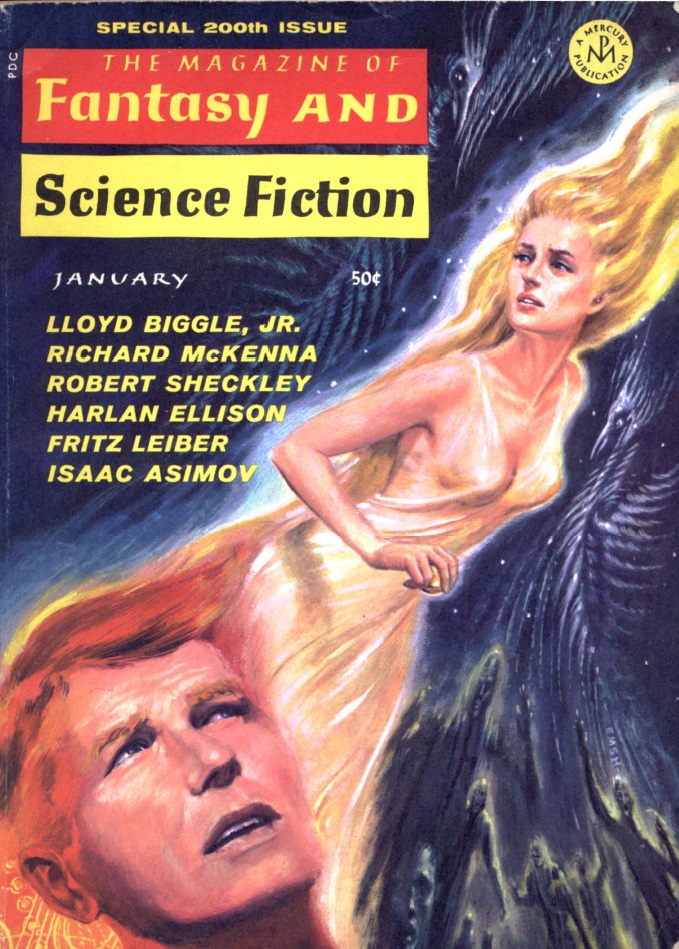

Dr. Shumway at a press conference last fall (l.), Mike Kasperak and his wife, Ferne (r.) This unpleasing collage is for Harlan’s new story. Art by Wenzel

This unpleasing collage is for Harlan’s new story. Art by Wenzel

![[February 4, 1968] More of the Same (March 1968 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/IF-1968-03-Cover-434x372.jpg)

![[January 10, 1968] Saving the Best For Last (<i>Dangerous Visions</i>, Part Three)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/1967_Dangerous-Visions-hc-672x372.jpg)

![[December 20, 1967] Smut! (January 1968 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/671220cover-672x372.jpg)

![[December 6, 1967] Brotherly Love (<i>Dangerous Visions</i>, Part Two)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/DangerousVisions1stEdxx971656156_465_692_int-2.jpg)

![[October 14, 1967] Threat level: High (October Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/671014covers-672x372.jpg)

![[October 10, 1967] Jack the Ripper and Company (<i>Dangerous Visions</i>,Part One)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/1967_Dangerous-Visions-hc-2-672x372.jpg)

![[July 16, 1967] The Weird and the Surprising (July 1967 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/670716covers-672x372.jpg)

![[April 12, 1967] We'll take Manhattan (<i>Star Trek</i>: "The City on the Edge of Forever")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/670412title-672x372.jpg)

![[February 4, 1967] The Sweet (?) New Style (March 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/IF-Cover-1967-02-full-672x372.jpg)

![[June 24, 1966] Increments: <i>World's Best Science Fiction: 1966</i>, edited by Donald A. Wollheim and Terry Carr](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/wollheim-66-cover-449x372.png)