by Gideon Marcus

It's been three years since our last survey of the American music scene. When last we took the pulse of Top 40, music was in a weird in-between stage with a dozen different genres and influences competing for ascendance. What we didn't see back then was the great tidal wave of musical influence that was about to crash on our shores from across the Pond. I think it's safe to say that 1964 was a watershed year, and the pop scene at least can be divided into the eras BBI and ABI…

The British Invasion

The tip of the spear was, of course, The Beatles. The right combination of talent, variety, and infectious tunes, all in a slick gray-suited, mop-topped package, the Fab Four were a hit in the U.S. from the moment they appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show in February '64.

What made The Beatles so compelling was that they had so much to offer. From their surprisingly diverse debut album, to their rocking second album, and on through their movie soundtracks, A Hard Day's Night and Help!, the British quartet had three score songs to enjoy, almost all of them hit-worthy.

And shoulder to shoulder with the boys from Liverpool was a host of other bands: The Dave Clark Five with their hard-hitting Glad All Over and Bits and Pieces, the delightfully varied and somewhat cynical The Kinks with hits ranging from All Day and All of the Night to the wistful Sunny Afternoon, the bluesy The Who with their anthemic My Generation, and The Rolling Stones, who certainly provide Satisfaction, Eric Burdom's soulful The Animals, the unusual The Zombies. More recently, The Hollies have impressed with I'm Alive and especially Look through any Window.

I enjoyed the sardonic A Well Respected Man quite a lot.

There are many Animals songs to choose from, but We Gotta Get Out of This Place is relentless!

Look Through Any Window blew us away!

Plus all the lighter Merseybeat gang, from Gerry and the Pacemakers to the goofy Freddy and the Dreamers, Peter and Gordon to Chad and Jeremy. The utterly gormless yet inexplicably popular Herman's Hermits. Not to mention the more musical theater-type stars like Petula Clark, Dusty Springfield, and Lulu.

Downtown is both upbeat and melancholy at the same time.

All in all, it's been a musical smorgasbord, so delightful that you almost don't mind how many former musical greats got cut off midcareer: who listens to Neil Sedaka or Rick Nelson anymore? And Elvis is barely hanging on.

Domestic Resistance

Nevertheless, the Yanks have both resisted and embraced the invasion. The Beach Boys have kept on plugging away since their 1962 debut with album after album, and they don't seem at all fazed by the foreign influx.

Motown remains King (Queen?) too: Acts like The Supremes, Martha and the Vandellas, The Four Tops, The Impressions, Dionne Warwick, etc. fill the Top 10 as often as any English band.

Stop in the Name of Love — we got Tony Randall, too!.

Sadly, Martha and the Vandellas were shortchanged to promote The Supremes — their Nowhere to Run To is a modern classic.

Walk on By is one of the loveliest songs ever recorded.

If there's anything that marks this era of music, it's how quickly it's changed. As doors open, they also close. 1964 saw the acme and crash of the surf guitar craze. Acts like The Ventures still steadily produce albums, but the rest of the scene has evaporated, again evolving into garage-y endeavors. The Chiffons, The Shirelles, The Ronettes, and many other girl bands have mostly dropped off the radar, Phil Spector's "Wall of Sound" being supplanted by the new raw aesthetic.

Folk to Folk Rock

Since the last wrap-up, folk music swelled to a crescendo and spawned a hybrid child with rock. In 1963, Bob Dylan hit it out of the park with his magnum opus, The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan. Though he continued in acoustic vein through 1964, by last year he had picked up an electric guitar, rasped his voice a bit more (yes, it was possible), and completely changed his sound. From Like a Rolling Stone to widely covered It's All Over Now Baby Blue, Dylan's harmonica-fused electrica has transformed the radio (whether you like it or not.)

Sure, there are still straight folk acts out there, including Joan Baez, Judy Collins, the superlative Donovan, and the recent Gordon Lightfoot, but rocking folk is where it's at.

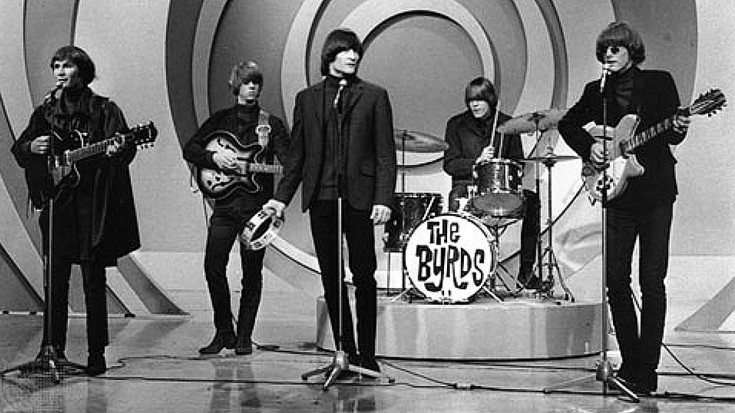

To wit, The Byrds released two of the more exciting records last year, featuring the hits Mr. Tamborine Man and Turn, Turn, Turn. Those are good songs, although they have lots of others that I like as well or better. For instance: It's No Use, I'll Feel a Whole Lot Better, and It Won't be Wrong. The group's jangle and close harmony are really appealing, though their Dylan covers tend to be limp.

Then there's the appropriately named We Five whose You Were on My Mind was everywhere (and deservedly so).

We saw a great performance of it on Hollywood Palace last year!

Simon and Garfunkel released an acoustic folk album at the end of 1964 that was pretty good but went nowhere. Lorelei and I liked the song, The Sound of Silence, so much that we played it at coffee shops and gigs for a while. Apparently others shared our taste because the song got air play on a lot of college stations, and a Byrds-ified version came out in September, dominating the charts. The duo, which apparently had broken up, got back together to release a new album: The Sounds of Silence (natch). It's quite good, though a bit downbeat, and more than half the songs incorporate electric guitar.

And in the same realm are The Mamas and the Papas and the closely associated Barry McGuire, evolved from the purely folkishy New Christy Minstrels. The M & Ps' California Dreamin' is destined to be an anthem for the decade, and McGuire's controversal Eve of Destruction and his even more goose-bump inducing This Precious Time mark two of the absolute highlights for 1965.

And we got to see BOTH of them on Hullabaloo late last year!

Given the success of the folk-rock genre, one can expect that the remaining "pure" folk acts may go in a rockish direction. But not necessarily…

Psychedelic

There's a new kind of music surfacing, filled with unusual effects, exotic instruments, and the impact of recreational drug use. For want of a better word, and because this is what several outlets and bands are calling it, the genre is "Psychedelic Rock."

Of all the bands I listen to regularly, probably the one that emblemizes this new style is the London-based The Yardbirds. Originally an uninteresting blues band, with the departure of guitarist Eric Clapton (who left because they stopped playing blues — don't let the door hit you in the a…mplifier on the way out) the band became something really far out. For Your Love, Heart Full of Soul, Still I'm Sad, and especially the latest single, Shapes of Things, are filled with atypical movements, eerie vocals, and just plain weirdness (but good weirdness) that indicates music has long since departed Kansas.

Other bands have begun experimenting with psychedelica, for instance, the formerly folk-rockish The Byrds with their brand new single, Eight Miles High. The frenetic, almost unfocused guitar work, the Indian inspired riffs, and the haunting vocals spell a huge departure from last year's output. The Beatles haven't whole-hog embraced the new style (yet), but the use of sitar on their last album, particularly on Norwegian Wood, is definitely part and parcel with it. I understand even The Beach Boys and The Rolling Stones are flirting with psychelica.

Next you'll tell me these bands are actually partaking! Le gasp!

Where to?

I don't think it's as hard to guess where things will be in 1968 or 1969 compared to how incomprehensible 1966 would have been to 1963 me. I'm guessing music will get weirder and heavier on one side, along a concurrent thread of smoother, poppish stuff. We might see two different radio formats arise by the end of the decade: one devoted to the experimental rock sound and one emphasizing smooth crooning and harmonies.

I sometimes marvel at how much I'm enjoying all of these new sounds. Many folks of my generation still cling to their jazz or even their classical albums and look at the new music as so much junk.

But to my ears, this is what I've been waiting for my whole life. Bring it on!

If you want to hear all of this great music, then tune in to KGJ, our radio station! Nothing but the newest hits!

![[May 4, 1966] Pushing the Envelope (The State of Music: 1964-66)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/660504mcguire-672x372.jpg)

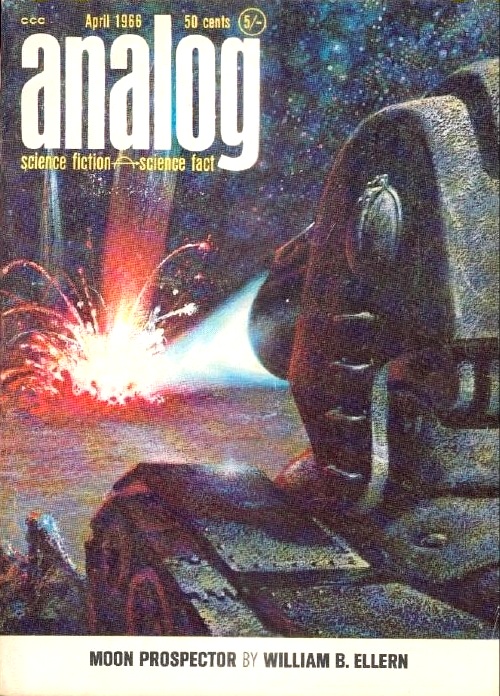

![[April 30, 1966] Ormazd and Ahriman (May 1966 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/660430cover-672x372.jpg)

![[April 16, 1966] Non-taxing (May 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/660416cover-664x372.jpg)

![[March 31, 1966] Shapes of Things (April 1966 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/660331cover-500x372.jpg)

![[March 22, 1966] Summer in the sun, winter in the shade (April 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/660320cover-672x372.jpg)

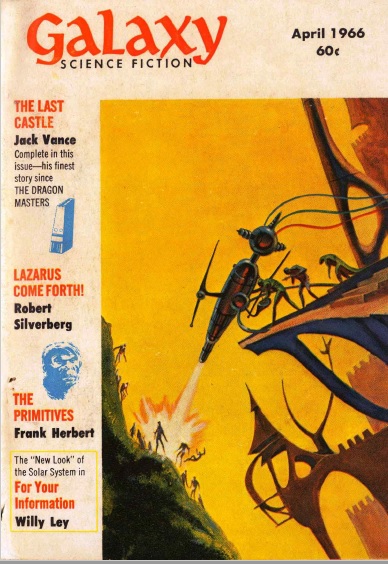

![[March 10, 1966] Top Heavy (April 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/660310cover-388x372.jpg)

![[February 18, 1966] Fixing up the old place (March 1966 <i>Fantasy & Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/660218cover-672x372.jpg)

![[February 10, 1966] Within and without (Isaac Asimov's <i>Fantastic Voyage</i> and Samuel R. Delany's <i>Empire Star</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/660210cover-672x372.jpg)

![[February 6, 1966] Hello, Stranger (exploring Space in Winter 65/66)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/660208luna9-539x372.jpg)