by Gideon Marcus

Five against Arlane, by Tom Purdom

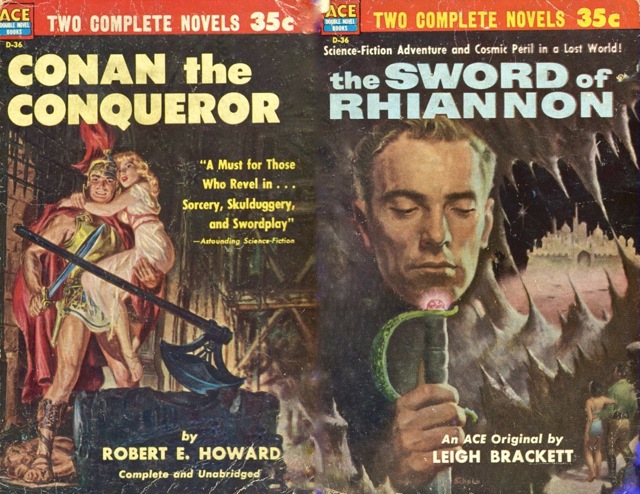

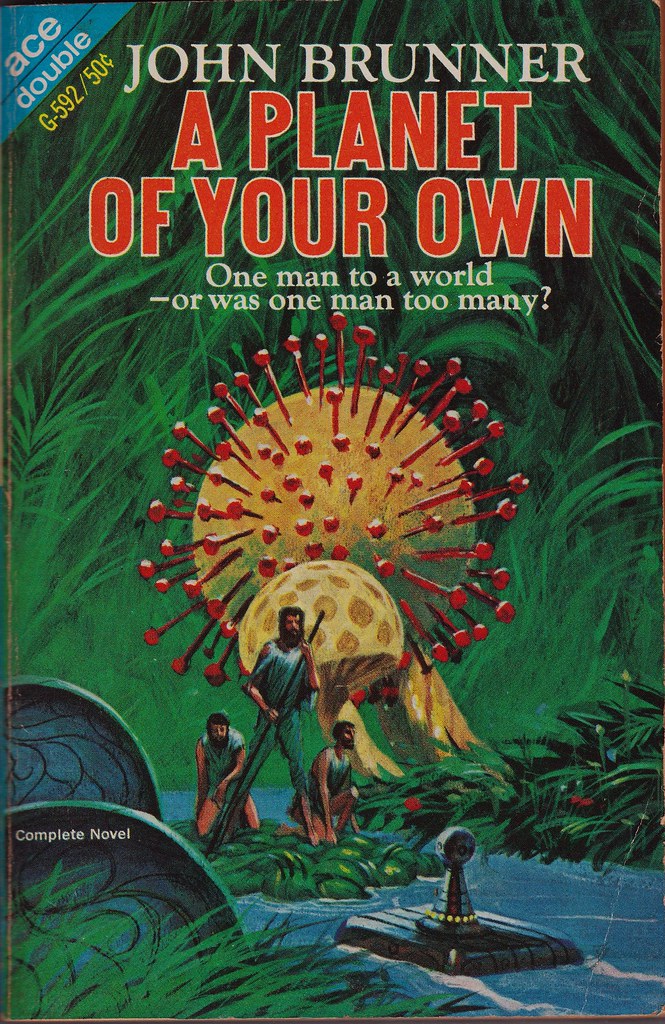

As you may know, I am a big fan of Tom Purdom. He's a very nice fellow, and his first book, I Want the Stars, was a stand-out. Thus, I was quite excited to see that the new Ace Double at the local bookstore featured my writer friend.

The first two chapters do not disappoint. We are thrown into the action as Migel Lassamba (explicitly of African descent; no lily-white casts in Tom's books) holds up a rich man and his personal doctor. His goal: to get an artificial heart for his companion and love, Anata. Why doesn't he just get one for free from the government hospitals? Because Migel, Anata, and three others are rebels whose goal is to topple Jammett, dictator of the planet Arlane. Five against Arlane, you see?

Thus ensues a ever-widening conflict between the outnumbered but canny rebel troops and Jammett, who resorts to increasingly draconian methods to retain control. His biggest ace in the hole is his ability to slap mind-control devices onto citizens. These "controllees" are fully conscious, but their bodies belong to the dictator, obeying his every whim. As Migel's cadre begins to turn the tide against Arlane's leader, the abuse of the controllees gets pretty grim.

There's a lot to like about this book. Arlane is a nicely drawn world, mostly tidally locked so its days last forever and only the pole is inhabitable. The descriptions of technology and society are largely timeless. Purdom is excellent at conveying material that will not be dated in a decade. As in Tom's other stories, we have intimations of free love and even polygamy/andry, and there is no real distinction between sex or race.

Sadly, where the book falls down is the execution. After those exciting first chapters, the chess-like contest between the rebels and Jammett feels perfunctorily written, as if Tom had to get from A to C, and he wasn't particularly interested in writing B. It almost reads like a chronicle of a homebrew wargame (ah, what a wargame this novel would make!) If I'd been the editor, I'd have sent it back and asked for…more. More emotion. More characterization. More reason to feel invested. And a more fleshed out ending (but perhaps that was a fault of the editing, not the writing).

I noted that the weakest parts of I Want the Stars and Tom's latest short story, Reduction in Arms, were the curiously detached combat scenes. Where Tom excels is the thinky bits. I suggest he either work harder on the fighting pits, or stick to thinky bit stories (like his excellent Courting Time).

Three stars.

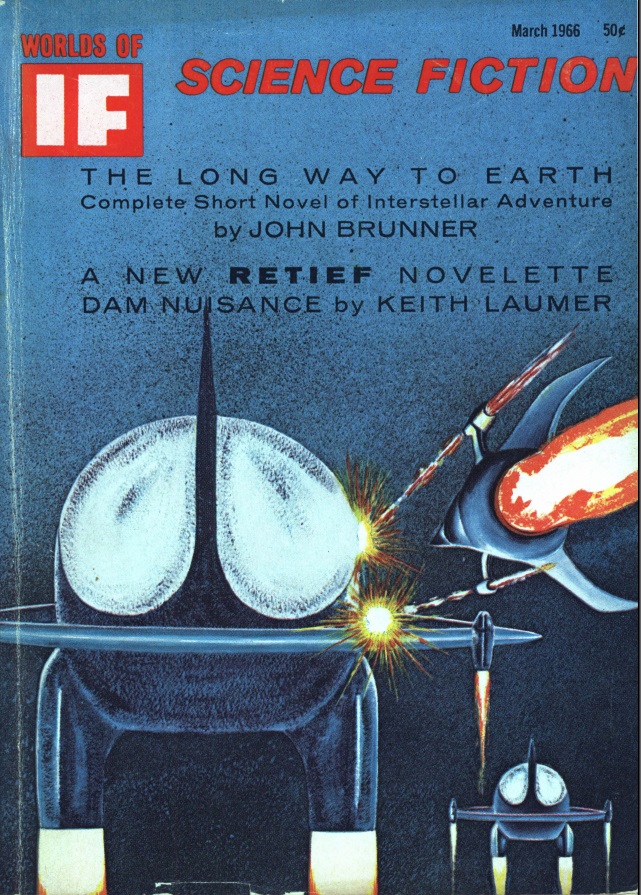

Lord of the Green Planet, by Emil Petaja

Emil Petaja is a new writer perhaps best known for his science fiction sagas based on the Karevala, the Finnish body of mythological work. Now, Petaja plumbs Irish myth for this truly strange, but also rather conventional science fantasy.

Diarmid Patrick O'Dowd (a fine Jewish name) is a scout captain for X-Plor, Magellanic Division. His flights of exploration frequently take him close to a mysterious, green-shrouded object. Finally unable to resist, he becomes the first of his corps to pierce the viridian veil. His ship crashes and disintegrates, leaving him stranded in a Celtic nightmare. On one side, the towers of the islands, inhabited by Irish lords whose beautiful works are created on the backs and tears of countless generations of peasants. On the other, the fetid swamps of the Snae–froglike magicians who seem to predate the human colonists. And up in the tower of T'yeer-Na-N-Oge resides the Deel, Himself, who rules over the world with a song whose lyrics none can deviate from, enforced by a panoply of beasts, flying, swimming, and creeping.

Of course, there is a personal element as well. The beautiful but utterly rotten-hearted Lord Flann plans to unite the islands and lead a crusade against the Nords. But first, he would marry his fair and kind cousin, Fianna. Fianna, on the other hand, has other designs. After rescuing Diarmid upon his arrival, she falls for the fellow, teaches him swordplay, and helps him fulfill his geassa to save the planet from the domination of the Deel. Along the way, there is plenty of swashbuckling, mellifluously articulate sentences, weird foes, and a twist.

It's pure fantasy, more akin to Three Hearts and Three Lions than anything else. But it's fun. And it has warcat steeds (Purdom's book has watchcats–I guess oversized felines are in this year).

Three and a half stars — and I'll wager Cora and/or Kris would give it four.

Triads

by Victoria Silverwolf

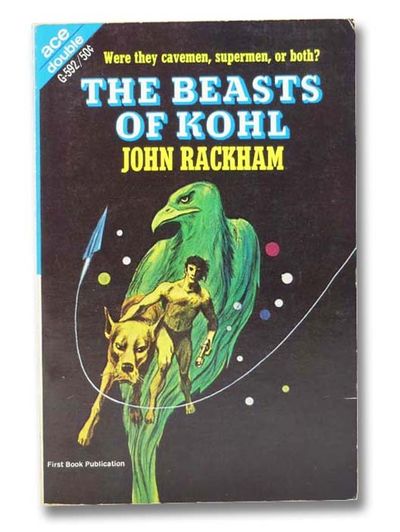

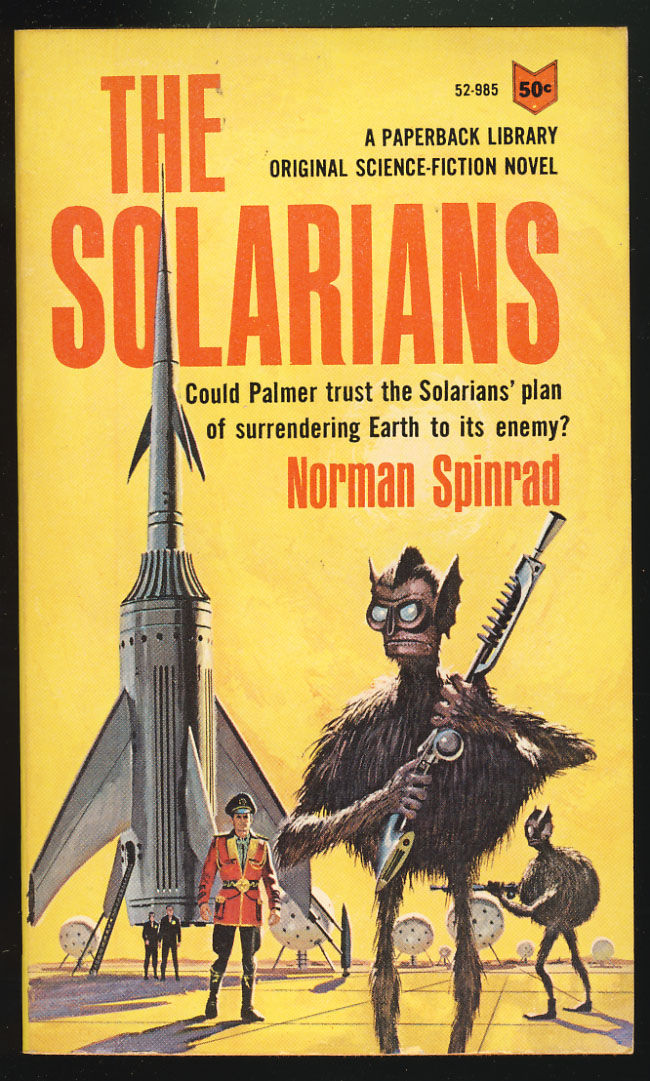

Two new science fiction novels deal with the relationships among three characters. As we'll see, in one of these the trio is very intimately connected. First of all, however, let's take a look at the latest book from an author known for prolificity.

Cover art by Robert Foster.

The novel begins and ends with the same words, spoken by two very different characters and having different implications.

Pain is instructive.

In this way, the author announces his theme from the very start. Thorns is all about suffering. Physical pain, to some extent, but, more importantly, emotional pain.

Duncan Chalk is a grotesquely obese, incredibly rich man who controls just about all forms of entertainment throughout the solar system. Secretly, he is also a kind of psychic vampire, feeding off the misery of others.

Minner Burris is a space explorer who, against his will, was surgically transformed by aliens. His two companions died during the procedure and he barely survived, monstrously changed outside and in. As a result, he is a loner, seen as a freak by other people.

Lona Kelvin is a teenage girl who had a large number of her ova removed and fertilized outside her body. The resulting babies were developed inside other women, or in artificial wombs. Although her physical appearance remains unchanged, the resulting publicity made her as much of an outsider as Minner.

Duncan's plan is to bring these two miserable people together, both as a form of voyeuristic entertainment for an audience of millions and to feed on their suffering. To win their cooperation, he promises to give Minner a new body and to allow Lona to raise two of the infants produced from her eggs as her own children.

At first, the pair simply share their mutual pain, sympathizing with each other. As Duncan sends them on a luxurious vacation to all the pleasure spots in the solar system, they become lovers. As he predicted, however, their differences soon lead to ferocious arguments. Minner sees Lona as an ignorant child, and Lona comes to hate Minner's bitterness and anger. Can they escape from Duncan's scheme, and find some kind of peace?

Reading this book is an intense, almost overpowering experience. It is the most uncompromising work of science fiction dealing with human suffering since Harlan Ellison's story Paingod. Although set in a semi-utopian future, the settings — a cactus garden, Antarctica, the Moon, Saturn's satellite Titan — are almost all stark and bleak. There are other characters I have not mentioned — an idiot savant, abused by his family; the widow of one of Minner's fellow astronauts, obsessed with him in a masochistic way — who offer more examples of the varieties of pain.

In addition to offering a vividly described, detailed future, Silverberg writes in a highly polished style, full of metaphors and literary allusions. I believe this is his finest work since the outstanding story To See the Invisible Man. With this novel, and his highly praised novella Hawksbill Station, I think we're seeing a new Silverberg, adding greater sophistication and more serious themes to his inarguable ability to produce an unending stream of fiction.

Five stars.

The Werewolf Principle, by Clifford D. Simak

Cover art by Richard Powers.

Andrew Blake is a man with a problem. First of all, that's not even his real name. He picked it at random.

You see, Andrew (as we'll call him in this review) was discovered in deep space, after having been in suspended animation for a couple of centuries. He has no memory of his past, although he is familiar with Earth the way it was two hundred years ago.

In order to discuss this novel at all, I need to talk about something that the author reveals about one-third of the way into the book. I don't think that gives too much away, but if you'd rather dive into it without knowing anything about the plot you should stop reading here.

Still with me? Good.

Andrew is actually an android, an artificially grown human being with a mind taken from another person. He was designed to copy the mental and physical forms of aliens he encountered while exploring other star systems. The idea is that he would record this information, then revert to his previous condition. It didn't quite work out that way.

Andrew shares his mind with two other beings. One is a wolf-like alien, although it has arms that allow it to carry things and manipulate objects. The other is a sort of biological computer, a relentlessly logical entity that often takes the form of a pyramid.

Andrew's body changes shape, depending on which mind has control. After a brief period of confusion, during which these alterations happen at random, Andrew recovers some of his memory. The three minds and bodies work together, evading the folks who think he's some kind of monster.

There's a lot more to this book than the basic plot. Simak throws in a lot of futuristic details. Notable among these are talking, flying houses, and aliens who are essentially the same as the brownies of folklore.

Not all of these concepts mesh together smoothly, although they provide proof of a great deal of imagination. The overly solicitous robot house offers some comic relief, and the so-called brownies may seem too whimsical for some readers. Otherwise, the novel is quite serious, even offering a mystical vision of the unity of all life in the universe.

My major complaint is a plot twist late in the book, revealing the true nature of a character I haven't even mentioned. It comes out of nowhere, depends on a wild coincidence, and creates an artificial happy ending.

Despite these serious reservations, I actually liked the novel quite a bit. It's not a classic, but it's well worth reading.

Three and one-half stars.

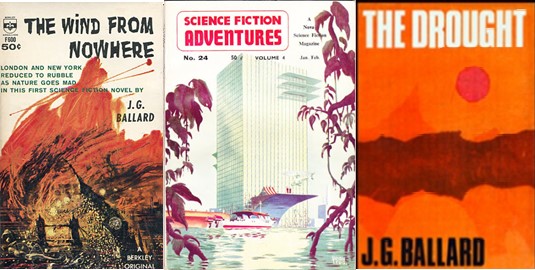

![[August 12, 1967] Planetary Adventures (August 1967 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/670812covers-672x372.jpg)

![[July 18, 1967] Highs and Lows (July Galactoscope #2)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/670718covers-672x372.jpg)

![[May 16, 1967] From the Sea to the Stars (May 1967 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/670516covers-672x372.jpg)

![[February 18, 1967] Six! Count them — Six! (February Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/670218covers-672x372.jpg)

![[January 14, 1967] First batch (January Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/670114covers-672x372.jpg)

![[December 10, 1966] Hot and Cold (December Galactoscope #1)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661210covers-672x372.jpg)

![[September 10, 1966] Bon appetit! (this month's Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/660910covers-672x372.jpg)

![[March 20, 1966] Two of A Kind (March Galactoscope #2)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Books.jpg)

![[February 20, 1966] An Embarrassment of Riches (February Galactoscope #2)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Montage-Image.jpg)

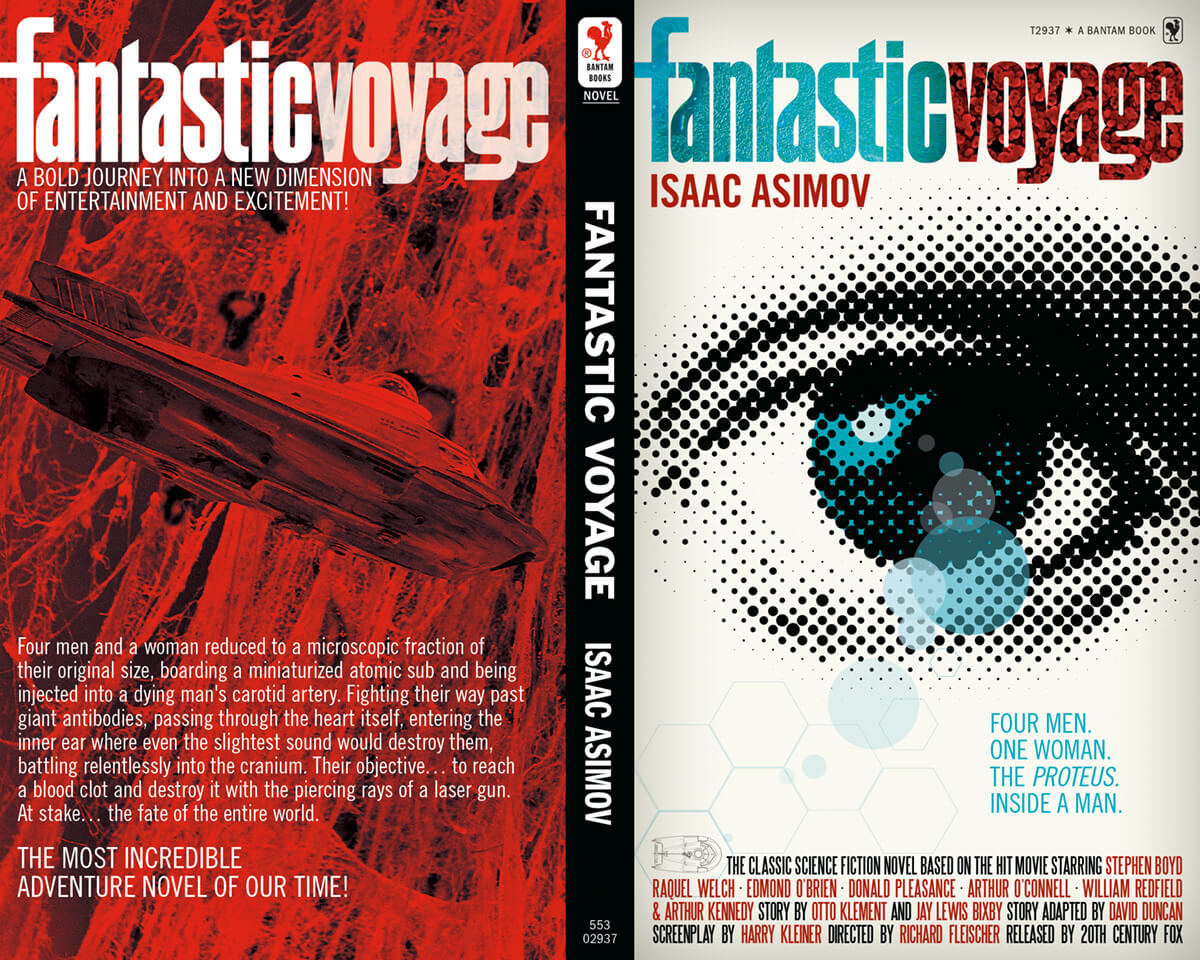

![[February 10, 1966] Within and without (Isaac Asimov's <i>Fantastic Voyage</i> and Samuel R. Delany's <i>Empire Star</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/660210cover-672x372.jpg)