by Mx. Kris Vyas-Myall

A Musical Introduction

Bob Dylan is in the middle of his sellout tour of England and folk revival is hitting the mainstream as a result. Dylan himself has 2 singles and 4 albums in the charts.

Also accompanying him on tour is Joan Baez who has reached mainstream attention with We Shall Overcome. Then we have home grown efforts such as the Iain Campbell Folk Group and Donovan, already proclaimed by some as The British Dylan.

At the same time Country is doing pretty well with King of the Road sitting at number 2 and Jim Reeves continuing his presence with Not Until Next Time.

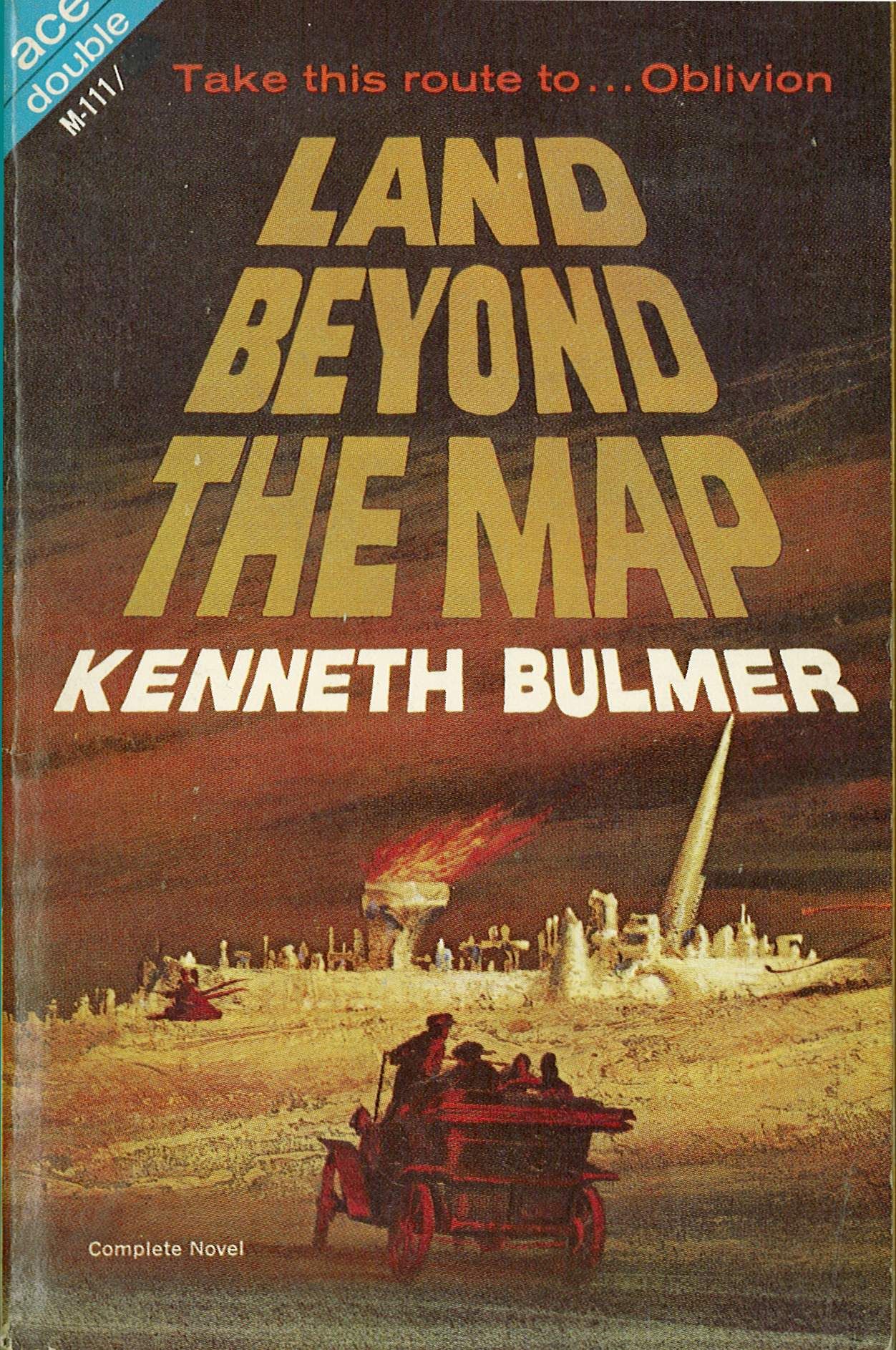

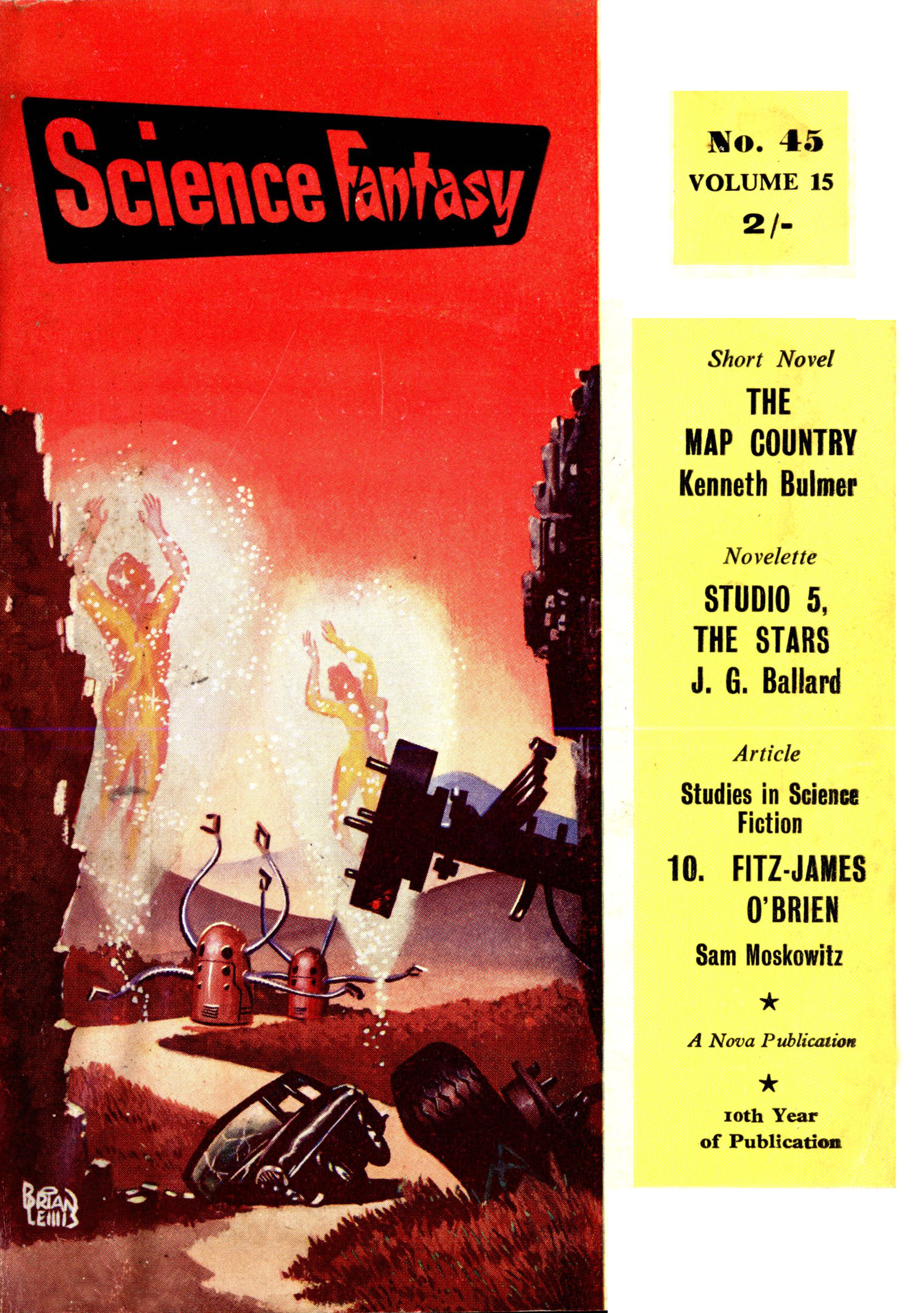

Whether this foreshadows a more permanent move away from the kind of pop music we have seen in the last few years remains to be seen. However, this is also true in today’s reviews, where the two books of May's first Galactoscopes represent a norm and a departure from it: Carnell presents us with a selection of tales representing many of the traditional themes of science fiction and we get a fantasy novel that is very much part of an older tradition.

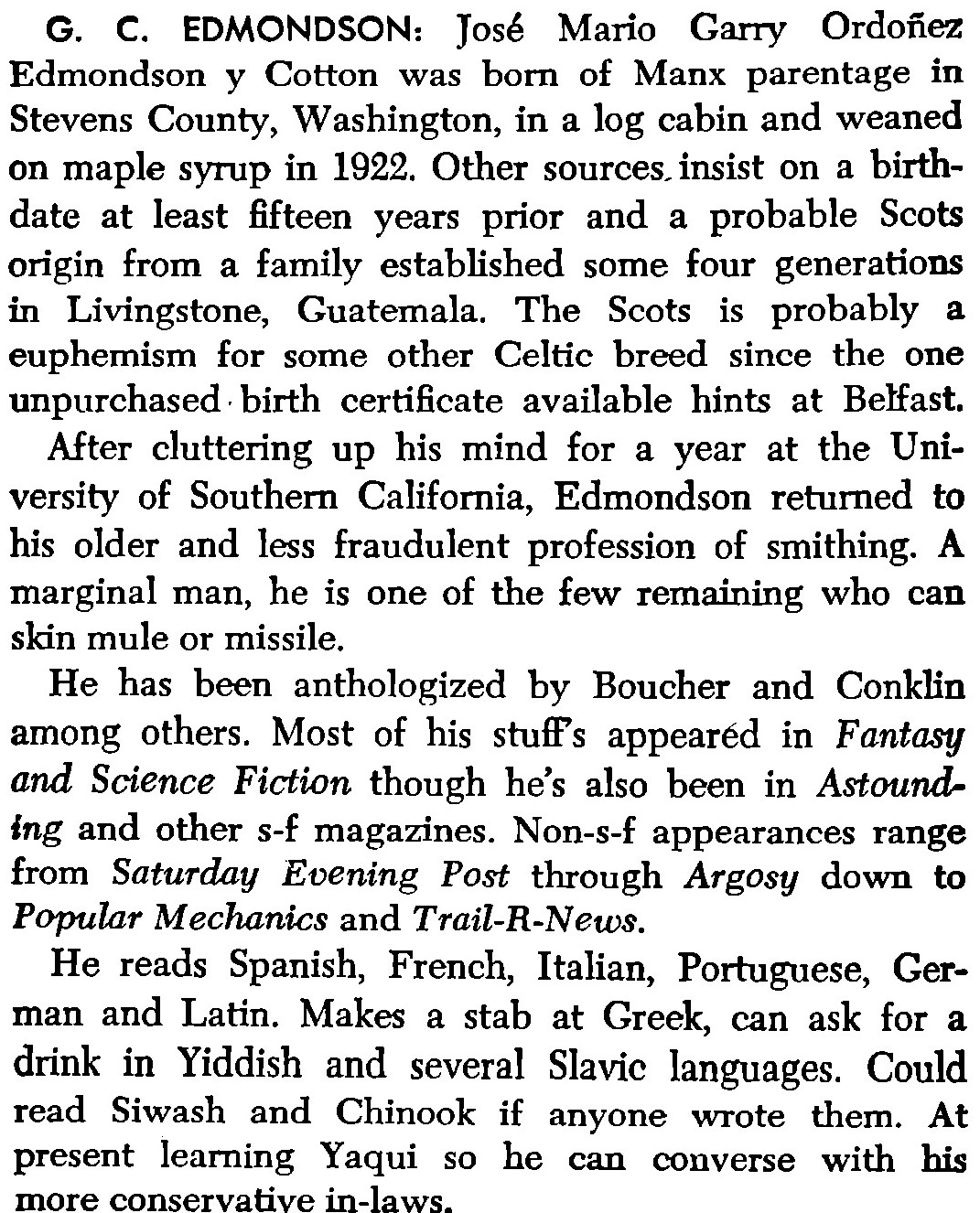

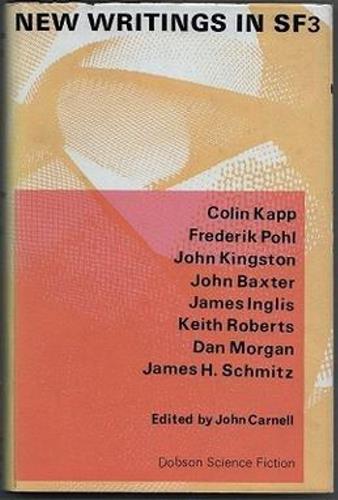

New Writings in SF4 ed. by John Carnell

John Carnell continues his quarterly anthology series, with another solid but unremarkable edition. Whilst he talks in his editorial about each edition having a particular flavour, it seems to me that they are pretty much of a piece. In fact the main difference here from last time is the presence of a slightly higher number of reprints.

This is not a new author but rather a new pseudonym for Keith Roberts, the ridiculously prolific writer for every British SF publication. In this piece Rick Cameron, a line maintenance boss at Saskeega Power, is investigating a series of deaths by electrocution, where people are apparently going too close to the lines. But is something else happening?

Unlike many I am not highly enamoured with Mr. Roberts' writing and the seeming combination of hard-boiled speech and use of offensive terms such as “halfbreed Indian” put me off this tale particularly.

Even putting that aside the main aim of this story seems to be to make electricity scary but doesn’t really succeed in doing it any more than it naturally is. It is certainly not the thought-provoking tale Carnell promises in his introduction.

One Star

Star Light by Isaac Asimov

The first of our reprints is this short vignette from the good doctor, originally appearing in Scientific American. Trent and Berenmeyer have stolen a fortune in Krillium, used to make robot brains, but now need to make a hyperspace jump to escape the police pursuing them.

I get the sense of Asimov writing on auto-pilot. It is not actually bad but if I was to get someone to write an imitation of his work it would end up something like this.

A high two Stars

Hunger Over Sweet Waters by Colin Kapp

On Hebron V, Blick and Martha are both stranded at floating processing stations after the power goes down and they set about working out how to survive.

The introduction says that Colin Kapp is “fast becoming one of our most popular sci-fi writers”, which is certainly news to me. Like The Dark Mind I thought this was fine, just a little old fashioned. This is the kind of problem story which would have looked at home in Astounding a decade ago. Well written, enjoyable but forgettable.

Three Stars

The Country of the Strong by Dennis Etchison

Our second reprint, this one from Seventeen magazine. This is a short evocative piece exploring a landscape after some kind of an apocalypse (probably a nuclear war from the description). Doesn’t have much meat to it but some good bones.

A high three stars

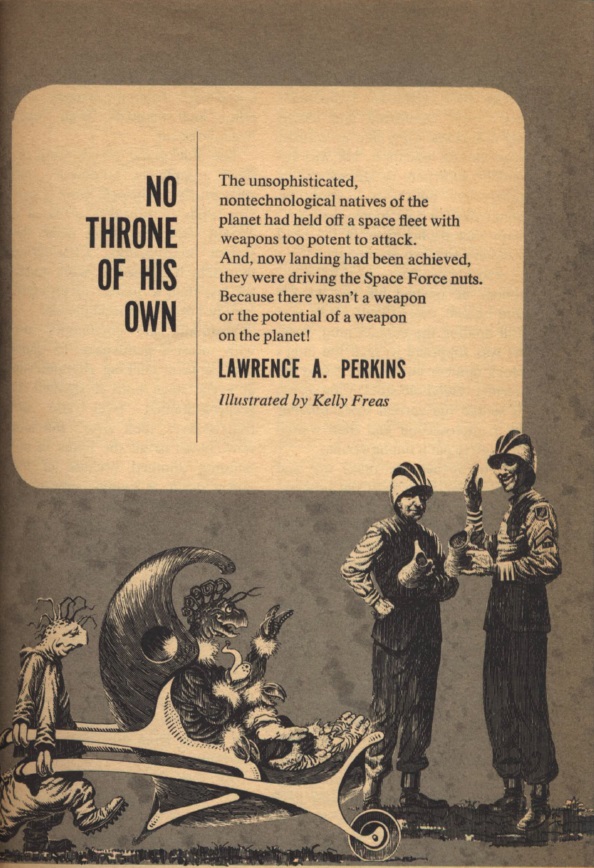

Parking Problem by Dan Morgan

A more silly satirical piece from another of the old New Worlds regulars. In the late twentieth century a solution to parking problems in inner cities is resolved by the development of extra-dimensional parking garages. Crunch and Pulver, two small-time criminals, attempt to break into one of these to steal high-priced vehicles.

Things end up taking a more surreal turn as it goes along and I found it quite sharp in the end.

Three and a half stars.

It seems you can never just have one Keith Roberts story in any issue, though this one appears without any pseudonym. Here he takes on subliminal messaging where drawings seem to be able to control people’s minds.

Whilst the subject matter is a rather well-trodden theme Roberts brings a great style to it and has an excellent twist ending.

Four Stars

Bernie the Faust by William Tenn

As noted in the introduction this piece, originally from Playboy, has already been reprinted in one of Judith Merrill’s excellent 'best of the year collections' (which I highly recommend), and it is easy to see why. Bernie is a salesman who has an unusual man, Mr Ogo Eskar, come into his store asking to buy increasingly more ridiculous things and thinks he is on to a great deal. But ends up regretting his choices.

As the name suggests, this is a modern take on the Faust story but with a nice twist and a real understanding of human psychology.

Four Stars

On the whole, a solid issue which got better as it went along. The only real disappointment was High-Eight and that could well be due to my aversion to some of Roberts’ work.

One other note. Paperback editions have started coming out for these from Corgi which, at 3/6 much more reasonable than the hardcover editions, at 16 shillings. Whilst I wouldn’t recommend picking these up over a copy of Science Fantasy and New Worlds, these are still very much worth the price.

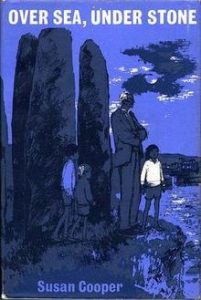

Over Sea, Under Stone by Susan Cooper

Whilst I had more books as a child than many people I knew, with a school teacher for a mother, juvenile fantasy was not as big as it is today. We had Edith Nesbit’s, TH White’s and Mary Norton’s stories, along with The Hobbit, but primarily I read more adventure stories in the style of The Famous Five or Swallows and Amazons.

It seems since the release of The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe there has been an explosion in excellent British fantasy stories from the pre-teen market. These include Roger Lancelyn’s Green take on King Arthur, Tom’s Midnight Garden, the Green Knowe and Alderley Edge stories, as well as more unusual works like Stig of the Dump or the Paddington books.

I now have a twelve-year-old sister and a nine-year-old brother who live in rural Ireland. As such they do not tend to see many of these books, so I like to try to find the best ones and send them over. This one certainly does not seem to be doing anything particularly new but looks like it could be another enjoyable series for the pre-teens.

We start off in the same mode as is traditional for British fantasy at least as far back as Nesbit, with a group of children (Simon, Jane and Barney) going to visit relatives in the countryside, this time their great uncle Merry in Cornwall.

The children decide to pretend to have a treasure hunt in the house they are staying in. In doing so they find first a secret attic filled with strange artifacts, then hidden within that, an ancient map. Taking it to their great uncle Merry they are told this relates to King Arthur, the battle between Good and Evil, and the Holy Grail.

In spite of the ominous tones that suggests for the story, it is actually rather an old fashioned jolly jape. Whilst there is a threat from another interested party, much of the time is spent with the three children (and a dog named Rufus) wandering around the countryside searching for clues. As such there is little doom and gloom but instead a real sense of fun.

One disappointment is the children feel rather thinly sketched here. In each of the Narnia books whoever is in the adventures has a distinct personality. Here it often feels Barney, Jane and Simon are interchangeable, merely serving the story function.

I am also trying to work out the time period this is meant to be set in. The children refer to the old fashioned way of speaking of some of the people in Cornwall but the main family still sound like they are from my childhood. Cooper was apparently inspired to write this story in response to a competition to write in the style of Nesbit so maybe this is an intentional artistic choice?

But in spite of my quibbles this is still an enjoyable story. What Cooper manages to do just as well as Blyton or Ransome have ever done is capture the joie de vivre of being a child having adventures in the English countryside and cast me back to my own young trips to Cornwall and Devon, clambering around Glastonbury or Tintagel hoping I might find the Sword in the Stone or a knight’s tomb. Certainly one I will be posting to my siblings when it comes into paperback and an author I will be keeping my eye on.

Rating: Three and a half stars

Coda

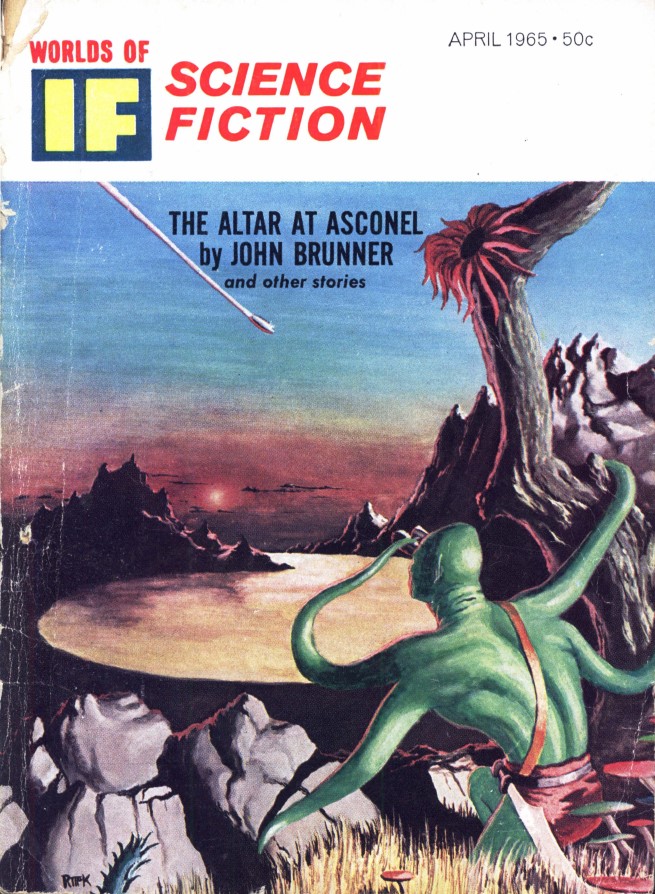

Is this a good direction for science fiction and fantasy? Honestly I think it can depend more on what the writer does with it. Both of these are enjoyable but not revolutionary publications. What I would like to see more of is works doing new things with these themes, as Tenn does with the Faust myth, rather than wholesale revivals as Doc Smith seems to be doing currently in If.

Whilst I wait to see which side it comes down on, I will join with the rest of the listeners of Big L in trying to guess what the actual the lyrics to Subterranean Homesick Blues are. Did he really sing "clients are in the bed book"?

Our last three Journey shows were a gas! You can watch the kinescope reruns here). You don't want to miss the next episode, May 9 at 1PM PDT, a special Arts and Entertainment edition featuring Arel Lucas, Cora Buhlert, Erica Frank…and Dr. Who producer, Verity Lambert! Register today and we'll make sure you don't forget.

![[May 6, 1965] Back To Our Roots (<i>New Writings in SF4</i> & <i>Over Sea, Under Stone</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/New-Writings-and-Over-Sea-Under-Stone.jpg)

![[April 14, 1965] Furious Time Travel (April Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/650414coversnew-672x372.jpg)

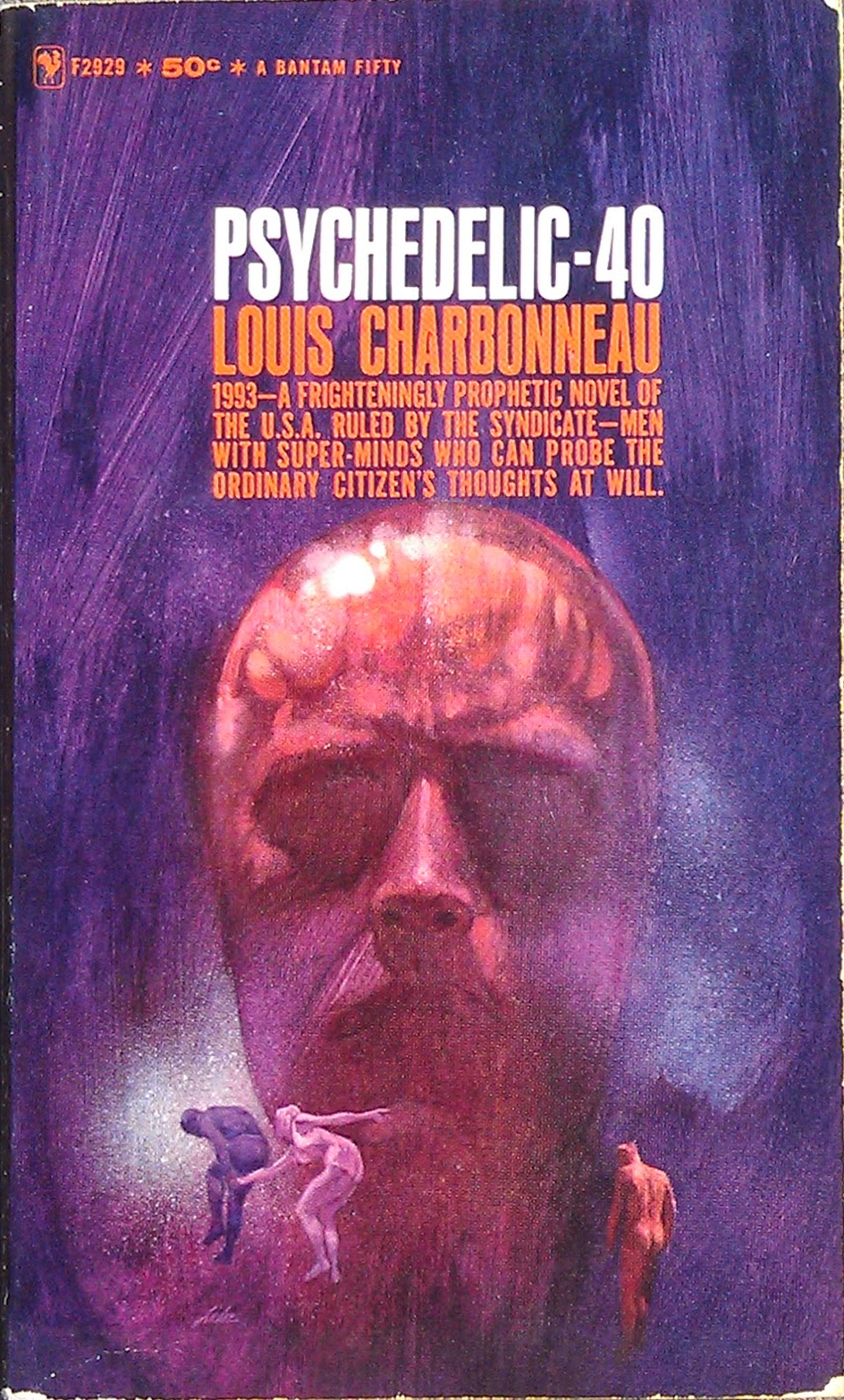

![[April 4, 1965] A Future of Rainbows: <em>Psychedelic-40</em>, by Louis Charbonneau](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/650404_PSI-40-672x372.png)

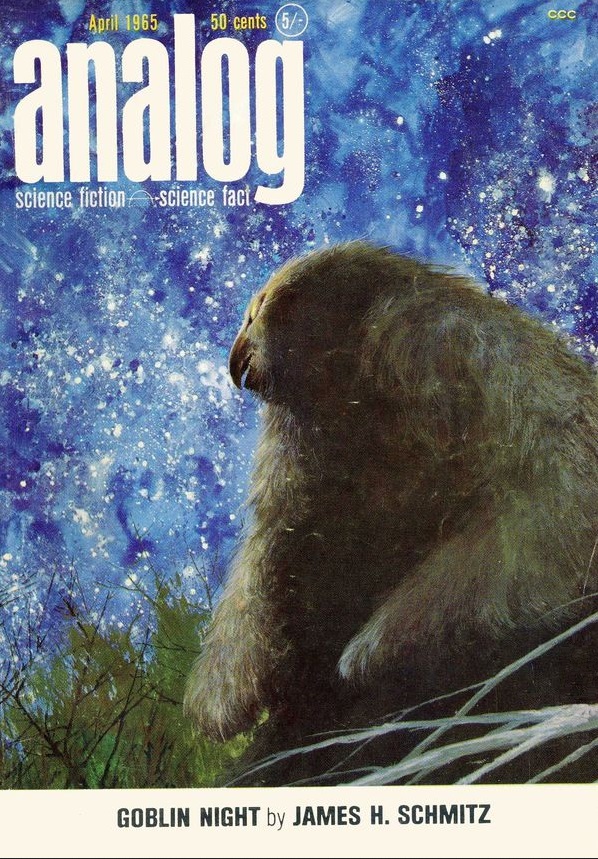

![[March 30, 1965] Suborbital Shots (April 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/650330cover-598x372.jpg)

![[March 28, 1965] Detectives, Curses and Time Travel <i>New Worlds and Science Fantasy, March/April 1965</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/SCF-April-1965-1-461x372.jpg)

![[March 20, 1965] Clash of The Old & The New (February 1965 <i>Gamma</i> & <i>City of a Thousand Suns</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/650320covers-672x372.jpg)

![[March 4, 1965] OLD WINE IN NEW BOTTLES (April 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/IF-march-cover-655x372.jpg)

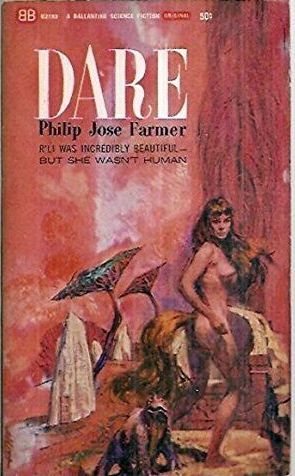

![[February 26, 1965] Dare to be Mediocre (February Galactoscope #2)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/650226covers-655x372.jpg)

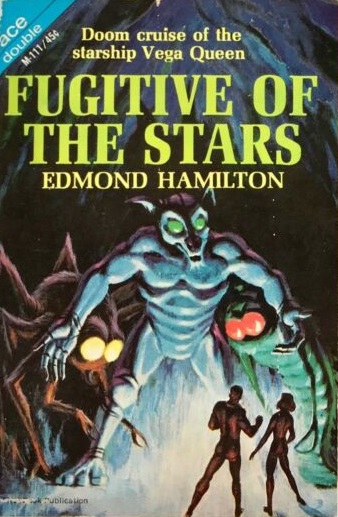

![[February 4, 1965] Space Prison of Opera (February Galactoscope #1)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/650206covers-672x372.jpg)

![[January 4, 1965] Madness: 2, Sanity: 1 (January Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/650104covers-672x372.jpg)