by Gideon Marcus

Turbulent times

Unless you've been living under a rock the past two years, you know the shockwaves from The 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago are still reverberating. The open fighting on the convention floor, the fascist polemic of Mayor Daley, the protests, the baby blue and olive drab helmets, and the crippled candidacy of the man tasked to thwart Dick Nixon from taking the White House.

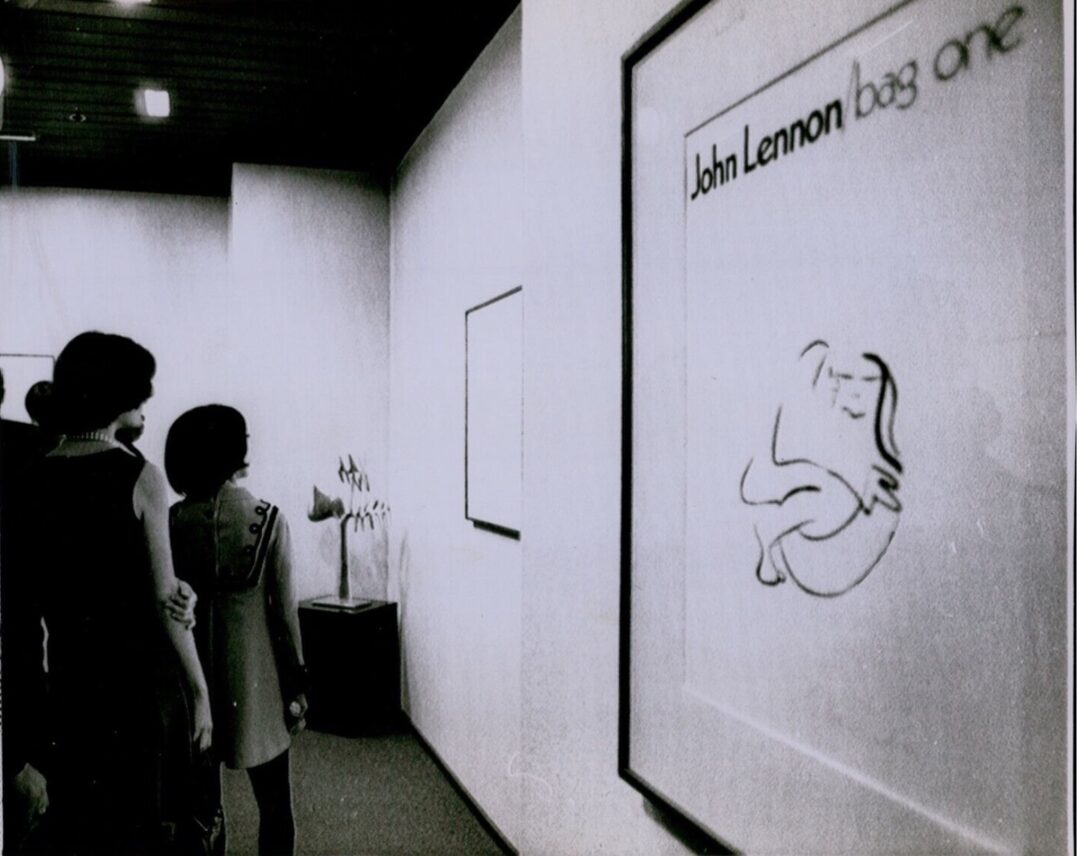

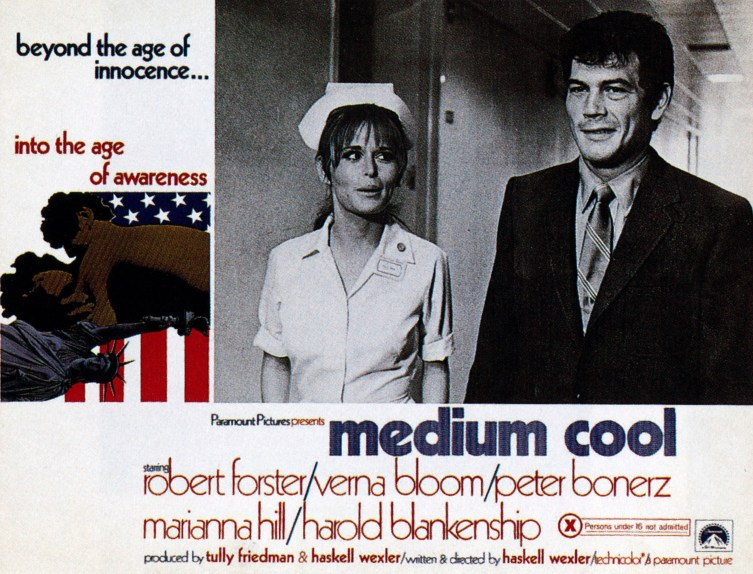

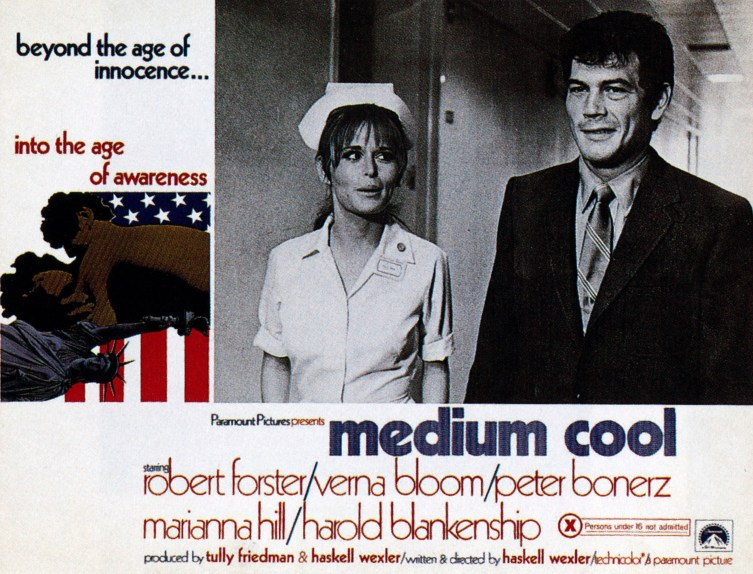

Aside from the shambolic shuffle toward further embroilment in southeast Asia, two other phenomena have kept the convention in the public eye. The first is last year's neck-clutch of a movie, Medium Cool. Half drama, half documentary, Haskell Wexler's film follows a jaded Chicago news cameraman in the weeks leading up to the crisis point. Indeed (and I didn't realize this at the time), the footage of Robert Forster and Verna Bloom in and around the convention hall during the clashes, hippie vs. fuzz, Dixiecrat vs. DFL, was all shot live.

Verna Bloom, playing an emigrant from West Virginia, searches Grant Park for her lost son

If you haven't caught the film, check your local listings. It may still be running in your local cinema. Be warned: it will take you back. If you're not ready for it, you will be overwhelmed.

Robert Forster is the news man. You'll recognize Marianna Hill (Forster's girlfriend) as a guest star in Star Trek's "Dagger of the Mind"

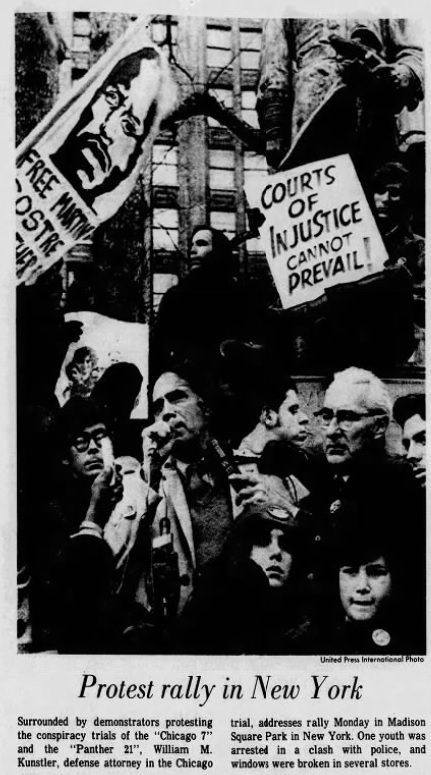

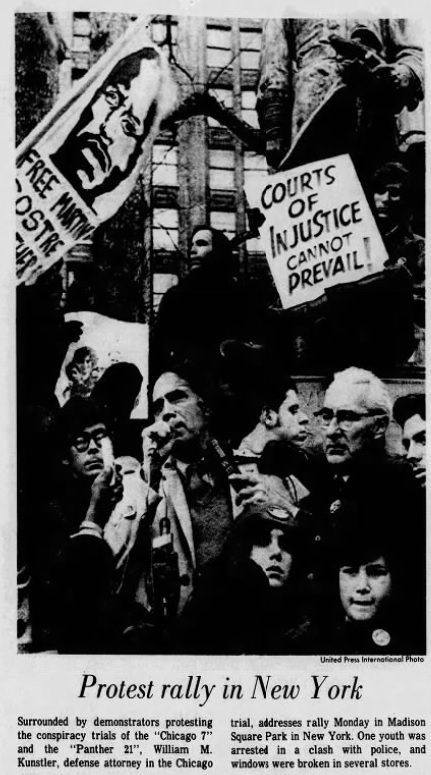

As for the other reminder, for the past two years, the papers have kept us apprised on the trials of the "Chicago Eight", charged by the United States Department of Justice with conspiracy, crossing state lines with intent to incite a riot. They included Rennie Davis, David Dellinger, John Froines, Tom Hayden, Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, Lee Weiner, and Bobby Seale.

(in the midst of his trial, Abbie Hoffman jumped on the stage at Woodstock during the performance of The Who to protest the incarceration of White Panther poet and musician, John Sinclair—it was a trippy scene)

Abbie Hoffman: "I think this is a pile of shit! While John Sinclair rots in prison…"

Pete Townsend: "Fuck off! Get off my fucking stage!"

Pete Townsend, just after recovering the stage

The verdicts came down on February 18, a mixed bag of positive and negative news for the accused. Apparently, four folks on the jury held out until the bitter end, but eventually went with guilty for some of the charges. The verdicts were:

Davis, Dellinger, Hayden, Hoffman, and Rubin were charged with and convicted of crossing state lines with intent to incite a riot. All of the defendants were charged with and acquitted of conspiracy; Froines and Weiner were charged with teaching demonstrators how to construct incendiary devices and acquitted of those charges. Bobby Seale had already skated when his case ended in mistrial.

Six of the "Seven": (l. to r.) Abbie Hoffman, John Froines, Lee Weiner, Jerry Rubin, Rennie Davis, and Tom Hayden

So, it's jail time for five of the eight while their cases go to appeal. You can bet that these results aren't going to lessen the flames of discontent in this country, at least for the vocal minority.

From page 3 of my local paper on the 24th

Steady and staid

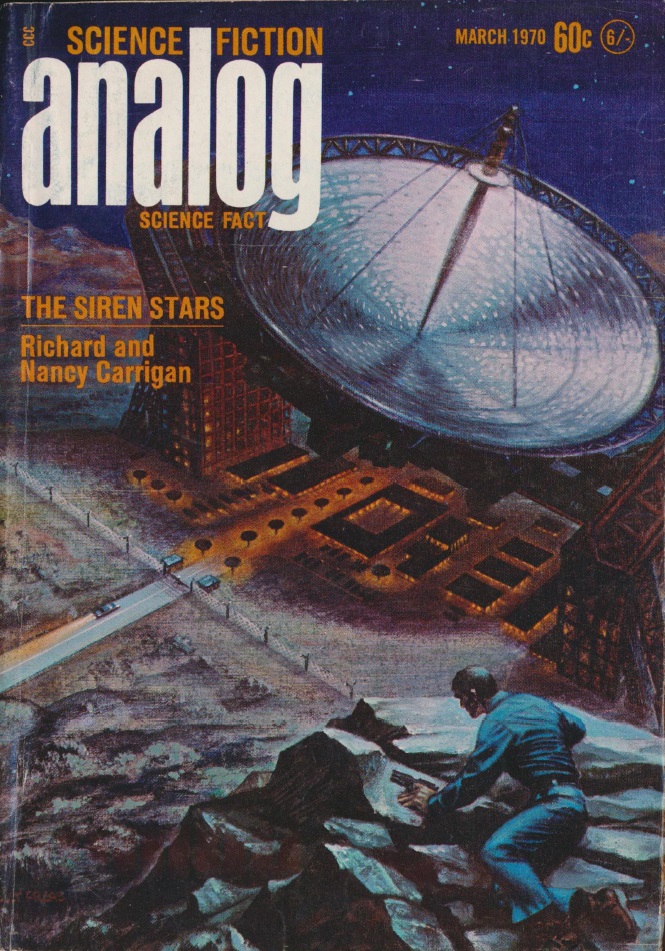

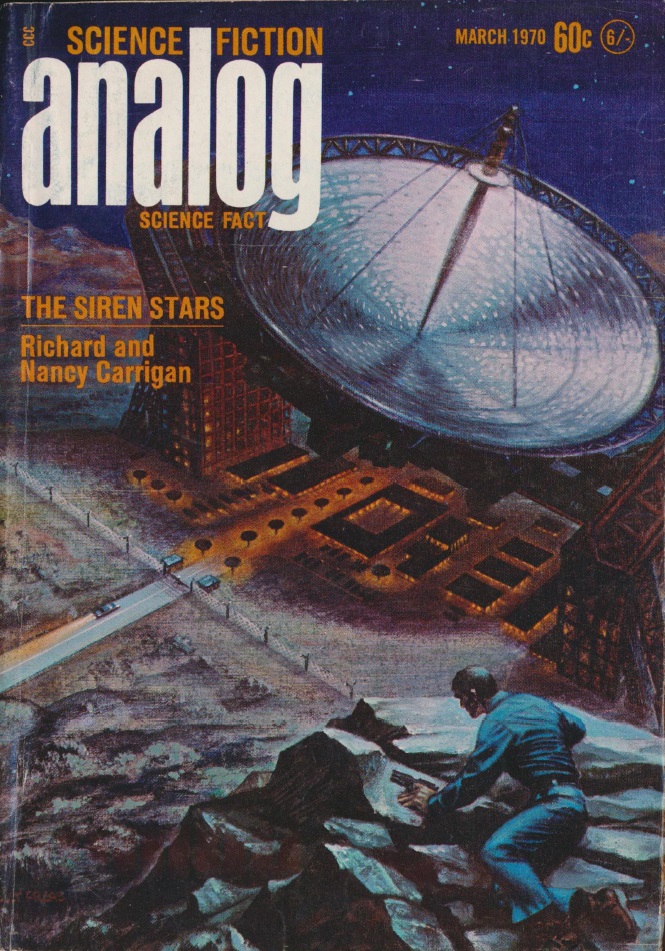

You wouldn't be aware of any of this turmoil if you lived under a rock and did nothing but read Analog Science Fiction. It remains a relic and deliberate artifact of a halcyon past as envisioned by editor John Campbell. The latest issue is a representative example.

by Kelly Freas

Continue reading [February 28, 1970] Revolutionaries… (March 1970 Analog) →

![[March 14, 1970] <i>To Venus</i> and <i>Hell's Gate</i>… are we <i>Out of Our Minds</i>?](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/700314covers-672x372.jpg)

![[March 12, 1970] It’s A Dog’s Life (<i>Orbit 6</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Orbit-F-672x372.jpg)

![[March 10, 1970] Baby, It's Cold (And Dark) Outside (April 1970 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/COVERSMALL-672x372.jpg)

![[March 8, 1970] They say that it's the institution… (April 1970 <i>Galaxy</i> and the incomplete Court)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/700308galaxycover-412x372.jpg)

![[March 6, 1970] <i>The Waters of Centaurus</i>, <i>And Chaos Died</i>, and <i>High Sorcery</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/700306covers-672x372.jpg)

![[March 4, 1970] Harry's Heroes (<em>Nova 1</em>, edited by Harry Harrison)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/NVFCNDXTDF1970-421x372.jpg)

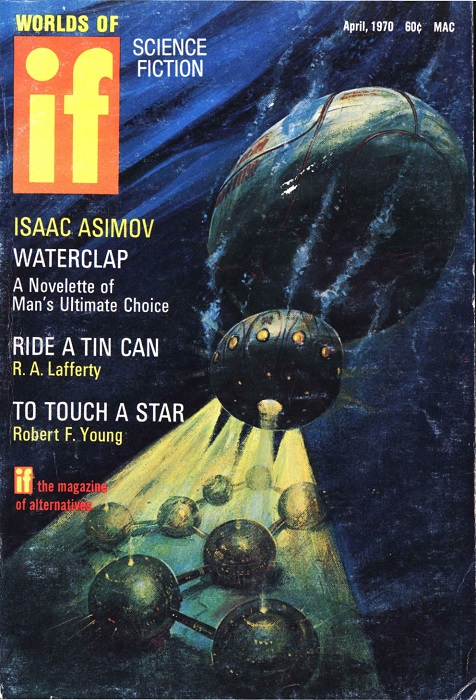

![[March 2, 1970] Par for the course (April 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/IF-1970-04-Cover-476x372.jpg)

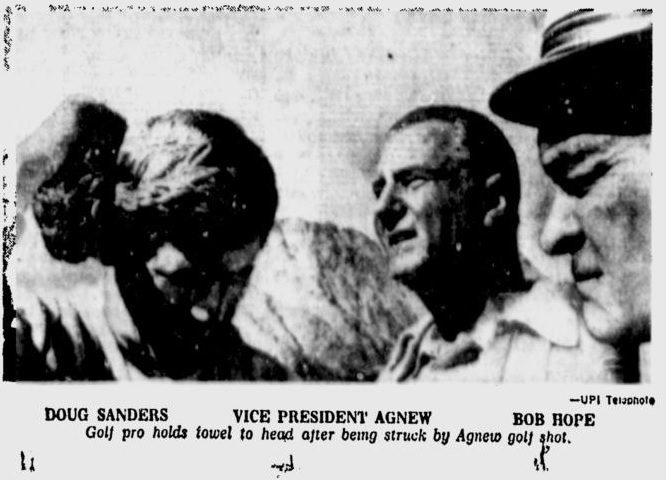

Wire photo of the aftermath.

Wire photo of the aftermath. Arrival at Ocean-Deep. Art for “Waterclap” by Gaughan

Arrival at Ocean-Deep. Art for “Waterclap” by Gaughan![[February 28, 1970] Revolutionaries… (March 1970 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/700228analogcover-665x372.jpg)

![[February 26, 1970] Made in Japan! (Ohsumi, first Japanese satellite)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Ohsumi-1-3-672x372.jpg)

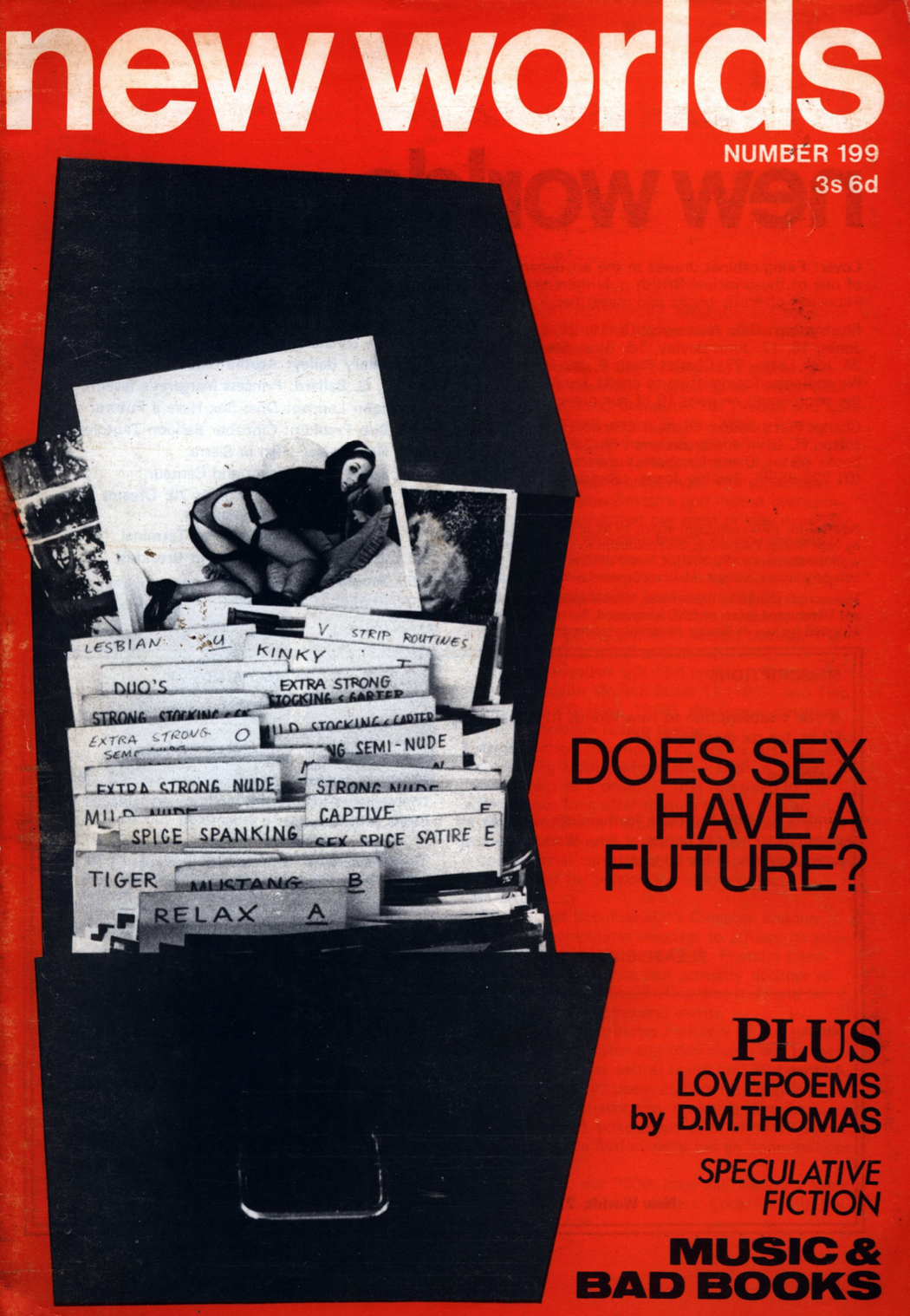

![[February 24, 1970] Sex and the Single Writer: New Worlds, March 1970](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/NW-1970-3-cover-672x372.png)