by Victoria Silverwolf

As my esteemed colleague David Levinson recently noted, war is currently raging, as it so often does, in various places around the globe. Fortunately, voices are beginning to be raised against this lamentably common human evil.

Benjamin Spock, the famous baby doctor, leads a group of folks protesting the conflict in Vietnam on a march to the United Nations in April of this year.

Whether these peace-loving people will have any effect on the escalating presence of American forces in Southeast Asia remains to be seen. Meanwhile, we can turn to the pages of the latest issue of Worlds of Tomorrow for a fictional look at an unusual way to change war into peace.

They Shall Beat Their Swords Into Plowshares

The cover reproduces, in shrunken and edited form, various illustrations from the pen of Virgil Finlay, subject of an article within the magazine. I recognize the one in the middle, showing the face of a ape-man, as coming from the January 1965 issue. Maybe some of you clever readers can tell me the sources of the others.

Project Plowshare (Part One of Two), by Philip K. Dick

Illustrations by Gray Morrow. I don't know if that artist also came up with the rather eccentric, pseudo-archaic introductory paragraph shown here. Maybe it's the work of the author, or possibly editor Frederik Pohl. In any case, it's very odd, not really in keeping with the mood of the novel.

The time is the early twenty-first century. There are references to space travel within the solar system, but that's way in the background. We have the usual flying cars and such that we're used to in tales of the fairly near future.

Like I said, flying cars. Also, people wear capes and funny-looking hats.

Our main character — I can't really call him the hero — is one Lars Powderdry. I assume his peculiar name is an allusion to the phrase keep your powder dry, attributed to Oliver Cromwell. The intent must be ironic, as Lars does the exact opposite of getting ready for battle (the literal meaning) and is not otherwise prepared for future events (the metaphoric meaning.)

That requires some explanation. You see, Lars has a most peculiar job. He's a weapons fashion designer. This is even weirder than it sounds. It involves going into a trance, with the aid of mind-altering drugs, in order to enhance his natural psychic abilities. While in this state, he perceives images of complex designs for very strange weapons. These are passed along to military folks, who in turn give them to manufacturers.

Why, then, do I say that Lars is not keeping his powder dry? That's because the so-called weapons are nothing of the kind. The elites make the ordinary folks think they are, but in reality the designs are used to make unusual consumer products, generally of a trivial, frivolous nature.

Here's an example, taken from a sidebar in the magazine. Again, I don't know if this is the work of the author or the editor.

In order to fool the public, the manufacturers produce faked films showing the phony weapons in action. This situation came about because of a secret agreement between the two sides in the Cold War. The ignorant masses believe their governments are ready to attack the other side, while their rulers avoid the possibility of a real, destructive war.

An example of the deception in action. The zombie-like guys, supposedly criminals subjected to the mind-destroying guns shown here, are really robots.

Lars has a counterpart on the other side, a woman named Lilo Topchev. Although he doesn't know anything about her, having only seen a photograph so blurry that it doesn't reveal anything at all, he feels an unexplained attraction to her. (The author doesn't say, but maybe this has something to do with their extrasensory powers.)

There's another woman in his life as well. Maren Faine runs the Paris office of his weapons fashion house. She's also his mistress. They annoy each other much of the time, but there seems to be genuine affection between the two. Their relationship has a touch of sadomasochism to it. Maren enjoys mocking her lover, who is well aware that he's not as smart as she is.

Maren Faine. The artist nicely captures her personality. Intelligent, capable, self-assured, cynical, and maybe a little bit cruel.

While visiting her in Paris, Lars finds a device made from one of the ersatz weapons he dreams up in his trance states. The gizmo is a sphere that answers questions. For most people, it's just a toy, sort of like a super-fancy version of those Magic 8 Ball things most of us have fooled around with.

Did I have one of these things? Reply hazy, try again later.

Lars treats the sphere more seriously, asking it about himself. He gets some uncomfortable answers, discovering that his reservations about the way he's helping the elite deceive the public aren't really a matter of ethics, but due to his own fears of losing his psychic powers.

Lars and the mechanical oracle.

As if that were not enough of a painful look into his soul, Maren is a bit psychic herself, able to detect her lover's subconscious emotions. She knows about his obsession with Lilo, for example, explaining it in Freudian terms.

Things get complicated when satellites appear in orbit, not launched by either side. Robots sent to investigate the objects are destroyed. The assumption is that they are the work of hostile aliens. Faced with the possibility of an attack by extraterrestrials, the elite bring Lars and Lilo together in Iceland. Their mission is clear. Work together, using their psychic abilities to come up with a design for a real weapon, or face the consequences.

An agent for the other side shows Lars what the consequences will be.

There's lots of other stuff I haven't mentioned. In particular, an important subplot involves an unpleasant fellow named Surley G. Febbs, who is drafted to become one of the six average citizens who work with the military, dealing with the designs envisioned by Lars. It's not yet clear what part he'll play in the plot, but I suspect it will be a vital one.

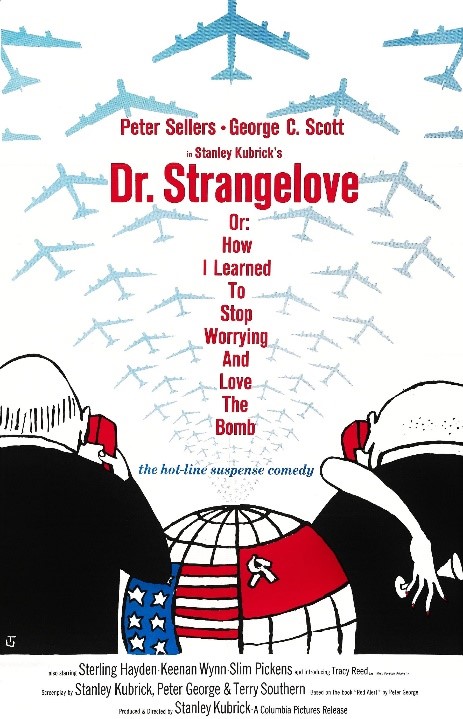

Although not a comedy, there's a strong satiric edge to this novel. Both sides in the bloodless Cold War engage the services of the same private espionage agency, which gives them just enough information to keep them paying for more.

The many characters are complex and varied, with flaws and quirks that make them seem real. (A notable exception: There's one minor character whose only function seems to be to have the author describe her breasts.) I'm definitely interested enough to wonder what's going to happen two months from now.

Four stars.

Me, Myself, and Us, by Michael Girdansky

This nonfiction article deals with the connections between the two halves of the brain, and what happens when they are cut. The author goes on to describe a highly speculative way in which to give someone two separate personalities in one body, making reference to the well-known story Beyond Bedlam by Wyman Guin. The suggestion is that such a person would be the perfect spy.

Cover art by Emsh.

Although there's some interesting information here, I found it distressing to read. Not only is the suggested creation of a human being with two minds disturbing, but the author describes real surgical experiments on animals that are horrifying. Maybe that's only my squeamishness, but I wish he had just talked about those unfortunate people who have had the link between the hemispheres of their brains severed.

Two stars.

Last of a Noble Breed, by Mack Reynolds

Illustrations by Normal Nodel.

We begin in the city of Estoril, Portugal, a luxurious resort community. A couple married for only six months is there for business as well as pleasure. The husband, a nuclear engineer, is trying to win a position by meeting with various members of the European upper class.

In this future world, being an aristocrat is vital to one's success. Annoyed by the snobs and a little drunk, the man half-jokingly announces that his wife's grandmother was the hereditary Sachem of the Cherokees, which is true enough. This leads to a worldwide movement to have the United States government restore tribal lands to her people, even though the woman is only one-quarter Cherokee, at most. (Her grandmother, whom she met exactly once, might not have been one hundred percent Cherokee.)

Uncle Sam faces a problem. I'm not sure what that sign is supposed to say. Unfair to what? Queens? That doesn't make sense, as a Sachem is not at all a monarch.

This isn't the most plausible premise in the world, even for a comedy. There are some enjoyable bits of satire, and the author provides some accurate information about the Cherokee people, as far as I can tell. But the lighthearted mood doesn't match well with the truly tragic history of the Cherokees. The husband has a habit of calling his wife a squaw, which annoys me as much as it does her.

Two stars.

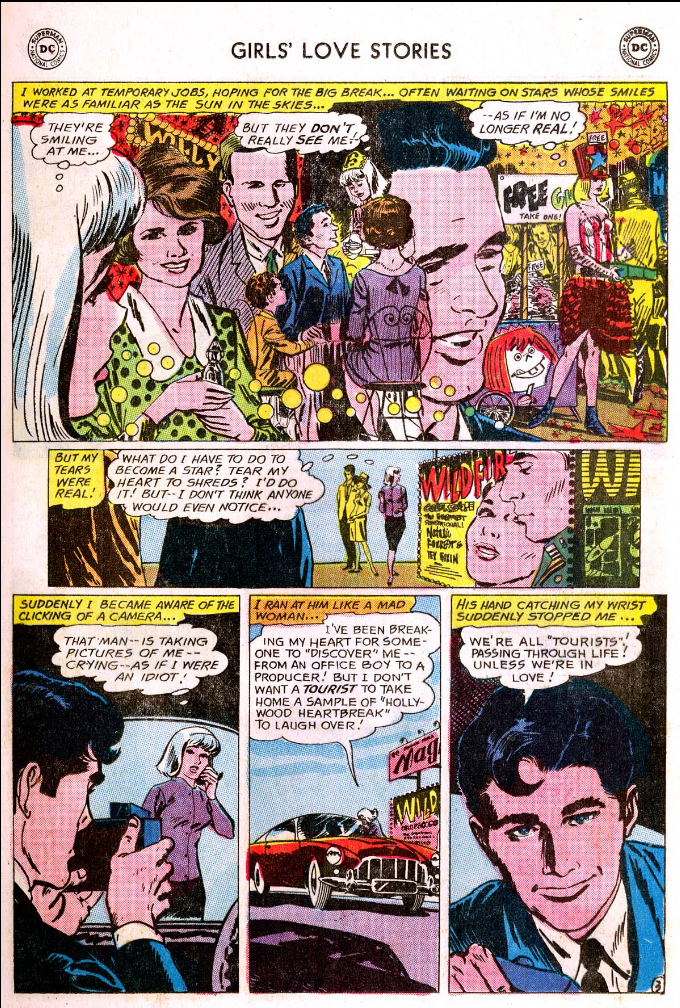

The Sightseers, by Thomas M. Disch

Rich people have themselves placed in suspended animation for thousands of years at a time, emerging to enjoy a lavish lifestyle for a while, then jumping back inside their time capsule. Oddly, things never seem to change. These time tourists stick to the fabulous hotels and restaurants that cater to them, which remain unaltered over millennia.

The only other people they encounter are the Nubians who serve their every whim. The suspension device breaks down, and a couple of the tourists, more curious than their much older consorts, investigate the world outside their sumptuous lodgings.

You'll probably predict the true nature of the Nubians, and why vast amounts of time appear to have no effect on the world. Although there are no surprises, the story is decently written. Disch has a knack for this kind of sardonic tale.

Three stars.

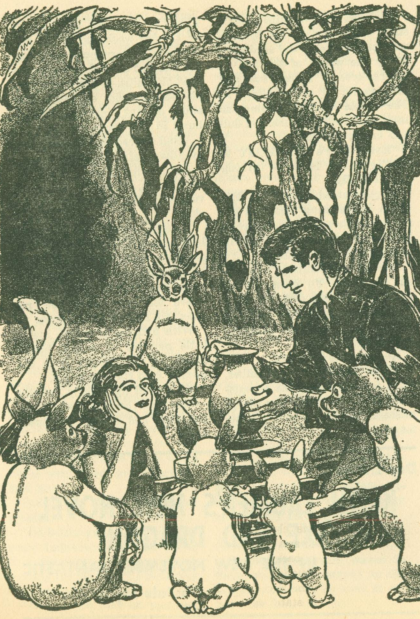

Virgil Finlay, Dean of Science Fiction Artists, by Sam Moskowitz

Here's a detailed biography and account of the career of a great talent. I don't know where the author dug up all of this information, but you'll learn a heck of a lot about the artist's life and work. There's only one problem.

No illustrations!

I know there are probably legal and budgetary reasons why this article doesn't include any examples of Finlay's drawings, but it's really frustrating to read about his artwork and not see it. In particular, Finlay's illustration for Robert Bloch's story The Faceless Gods, from the May 1936 issue of Weird Tales, is talked about quite a bit. We're told that readers were excited by it, and that H. P Lovecraft even wrote a poem about it. At least we get half of the poem, but we have no clue what the illustration looked like.

To save you from the same agony I underwent, I dug deep into piles of moldering old pulps and pulled out the drawing, as well as the complete poem. You're welcome.

Two stars.

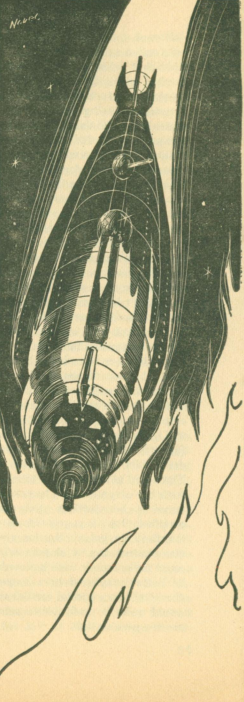

Worldmaster, by Keith Laumer

Illustrations by John Giunta.

The narrator is the sole survivor of a huge space battle. Both sides were completely destroyed. It turns out that this was deliberate on the part of the admiral who directed his side of the battle. He held back his gigantic flagship, which would have won a victory without the loss of the other vessels in his fleet.

His plan is to return to Earth in command of the only remaining warship, and thus take control of the planet. (Apparently this takes place at a time when the Cold War has heated up, but only in space. We're told that planetary forces are of little importance.)

And there are flying cars.

He offers the narrator the opportunity to join him, but our hero refuses. A couple of goons try to kill him, but he overpowers them and manages to get back to Earth through trickery. What follows is a series of chases and fight scenes, as the narrator tries to stop the admiral's fiendish plan.

And there's a big fire.

Typical for the author in his action/adventure mode, this story moves at a breakneck pace, and features a protagonist who overcomes all obstacles with wits, fists, and not a little luck. It's an efficient example of that sort of thing.

Three stars.

We started off with peace disguised as war, and wound up with the aftermath of war. Was it worth fighting for? Well, Philip K. Dick's novel-in-progress definitely piques my interest, although I suspect it will not appeal to all tastes. The rest of the issue is something of a disappointment, like a hasty retreat after an inconclusive skirmish. At least the only casualties of the conflicts inside these pages are imaginary ones. There are far too many in the real world. I wish you all peace.

The design scrawled on this guitar case, spotted on the campus of the University of California at Berkeley this year, was created by British pacifist Gerald Holtom, as a symbol for the nuclear disarmament movement. It has since shown up a lot of places, as a sign for peace in general. I like it.

![[September 16, 1965] Blessed Are The Peacemakers (November 1965 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v03n04_1965-11_0000-2-395x372.jpg)

![[September 14, 1965] The Face is Familiar (October 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/650914cover-551x372.jpg)

![[September 12, 1965] So Far . . . Well, Fair (October 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/amz1065-cover-497x372.png)

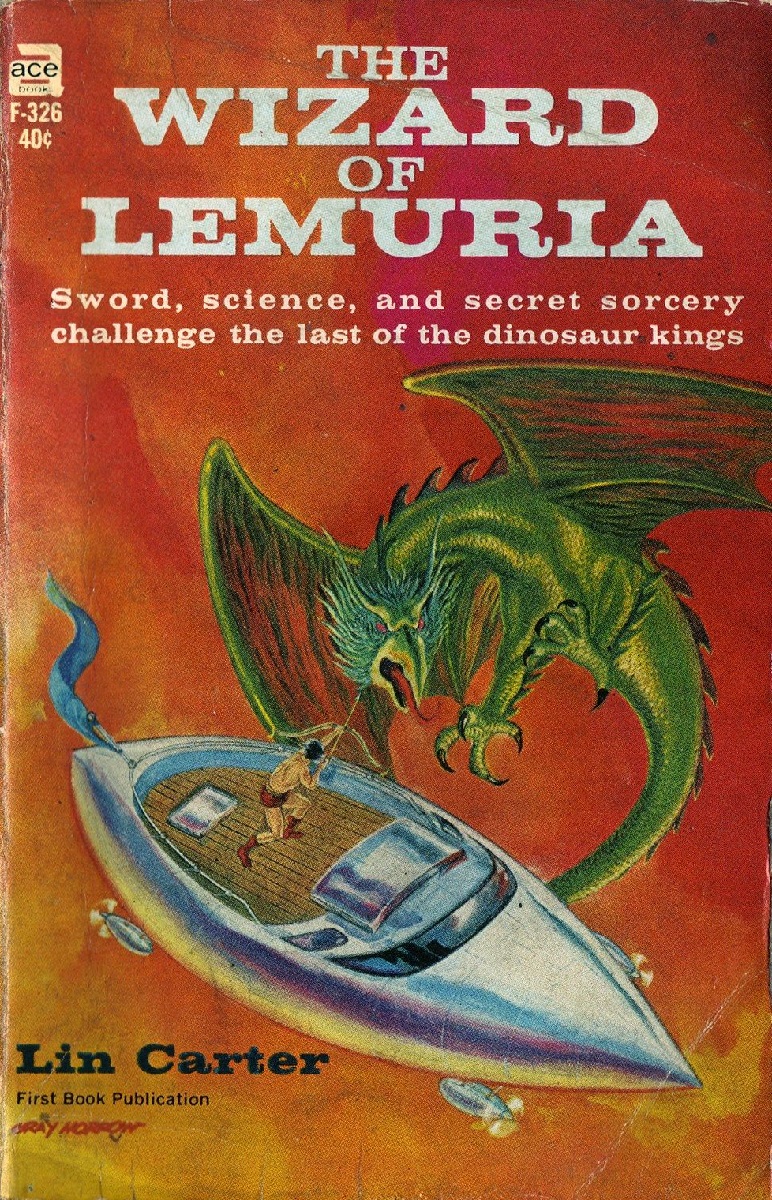

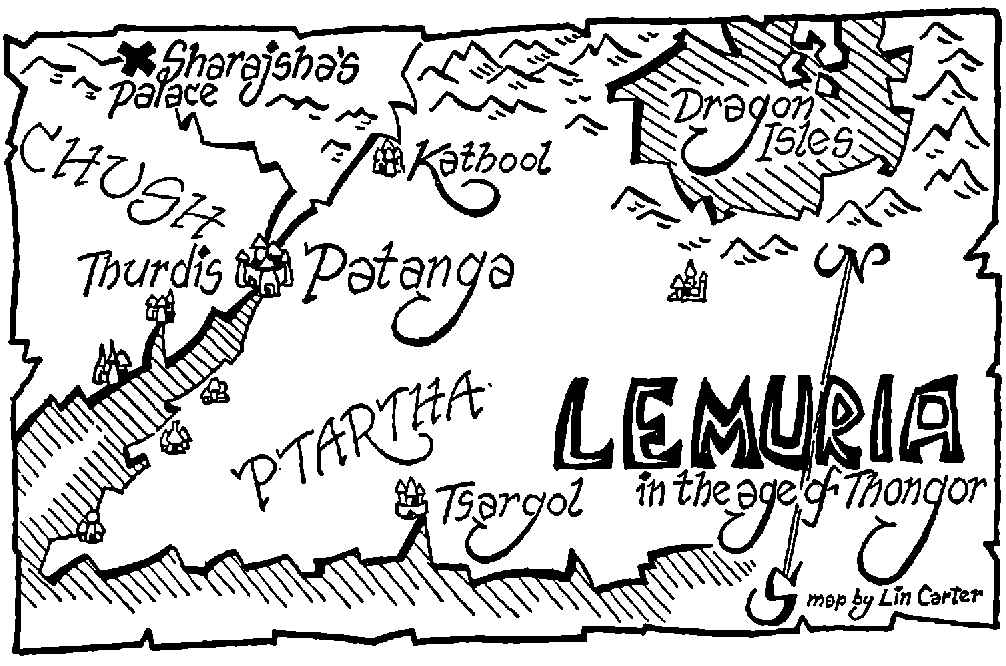

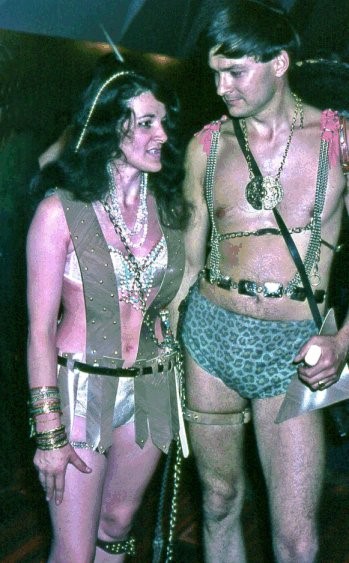

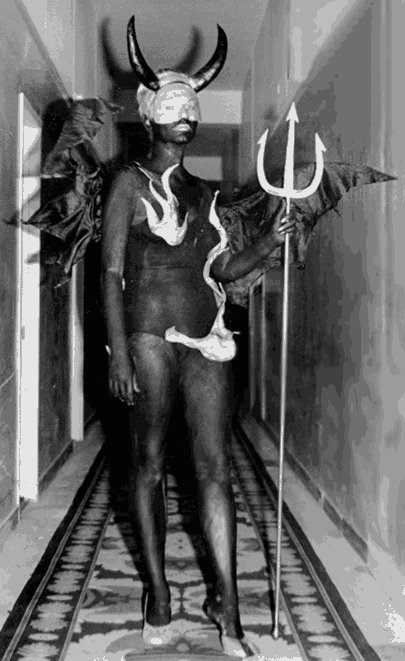

![[September 10, 1965] So Many Thews (Lin Carter's <em>The Wizard of Lemuria</em>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Cover-Wizard-of-Lemuria-672x372.jpg)

width="150"/>

width="150"/>

![[September 8, 1965] Still a Stranger in a Strange Land (<i>THE STRANGER</i> SERIES 2, AUSTRALIAN TV SF)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/The_Stranger-5.png)

![[September 6, 1965] War and Peace (October 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/IF-1965-10-cover-657x372.jpg)

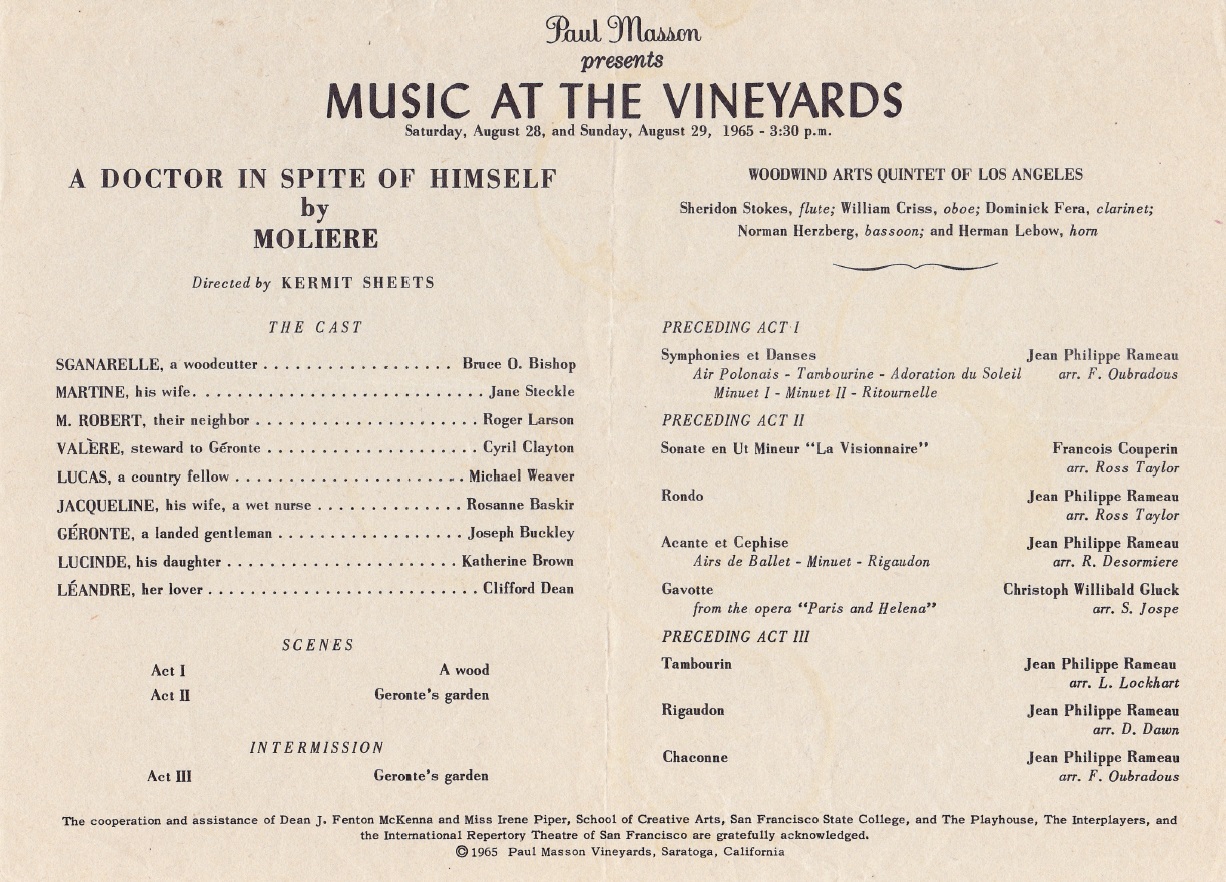

![[September 4, 1965] Doctor's Orders (Review of "A Doctor in Spite of Himself")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Moliere.jpg)

![[September 2, 1965] A Clash of Cultures (THE 1965 WORLDCON)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Worldcon_1965_London_logo.jpg)

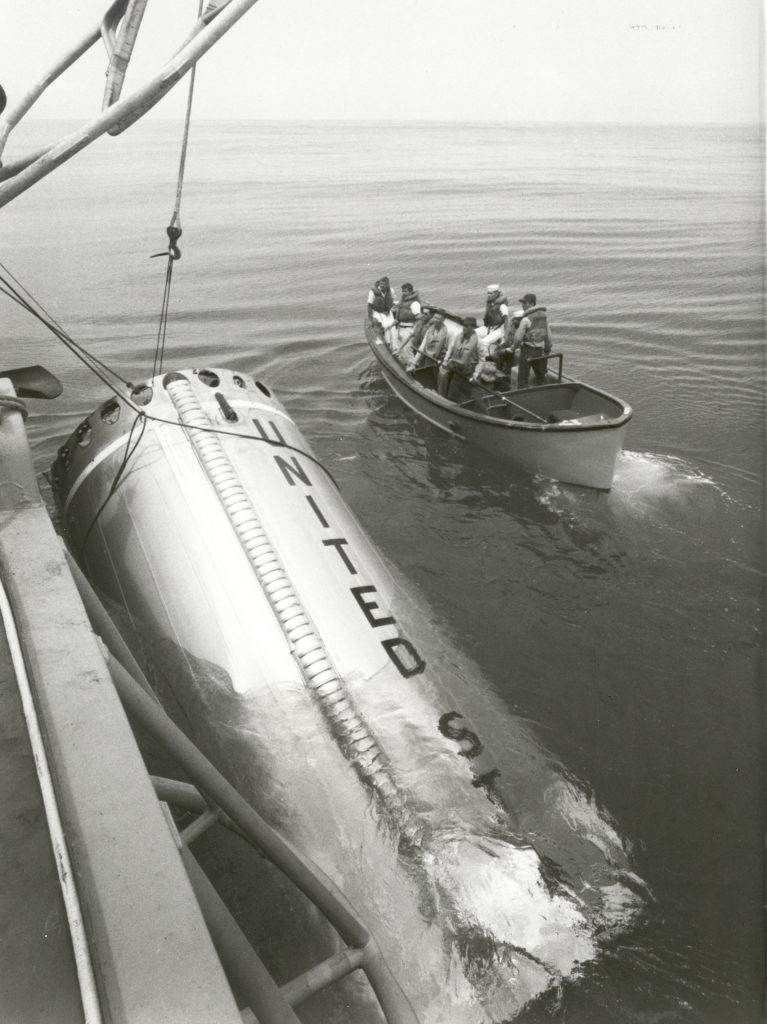

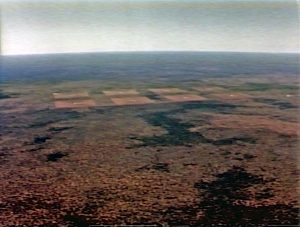

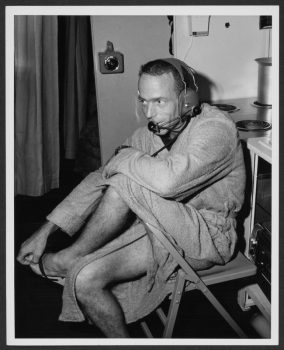

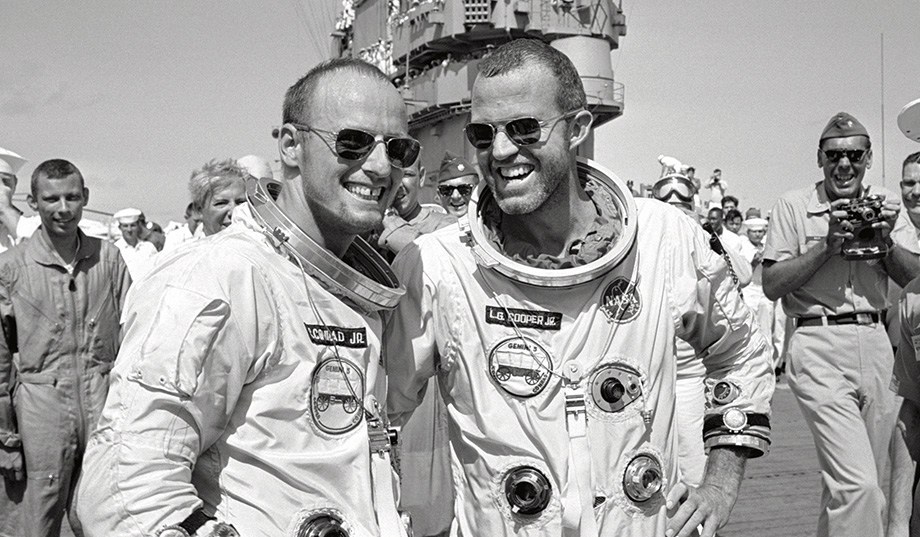

![[August 30, 1965] 8 Days or Bust! (Gemini 5's epic space mission)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Cooper-and-Conrad-672x372.jpg)

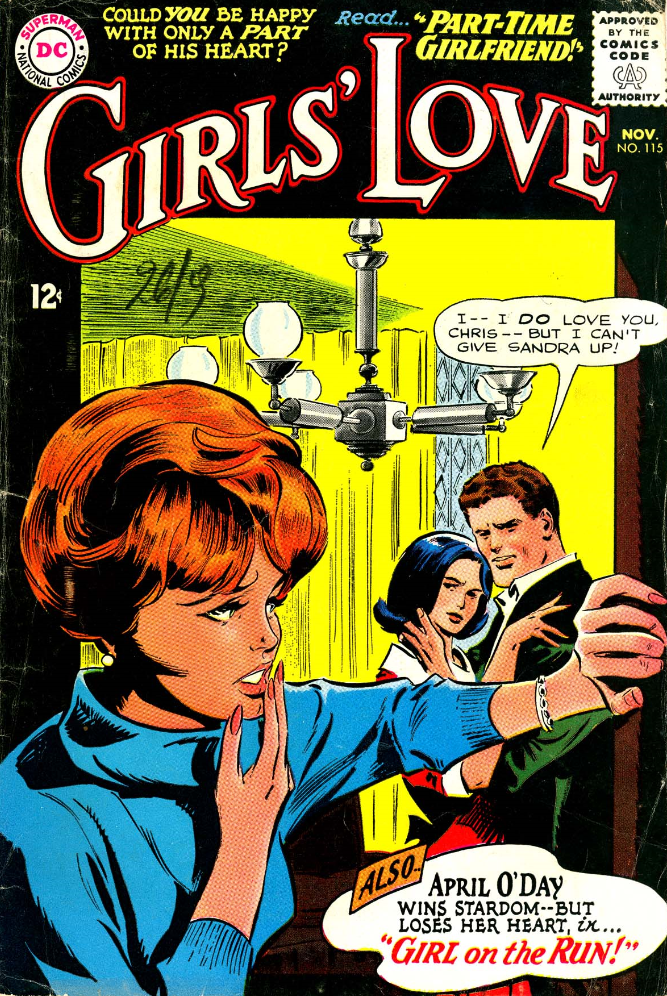

![[August 28, 1965] Love is My Superpower (Reviewing <i>Girl's Love Stories</i> #115)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/girlslovestories115-667x372.png)