by Cora Buhlert

For a Modern West Germany

The streets of West Germany are currently plastered with campaign posters, because a federal election, the sixth since 1949, will happen on September 28.

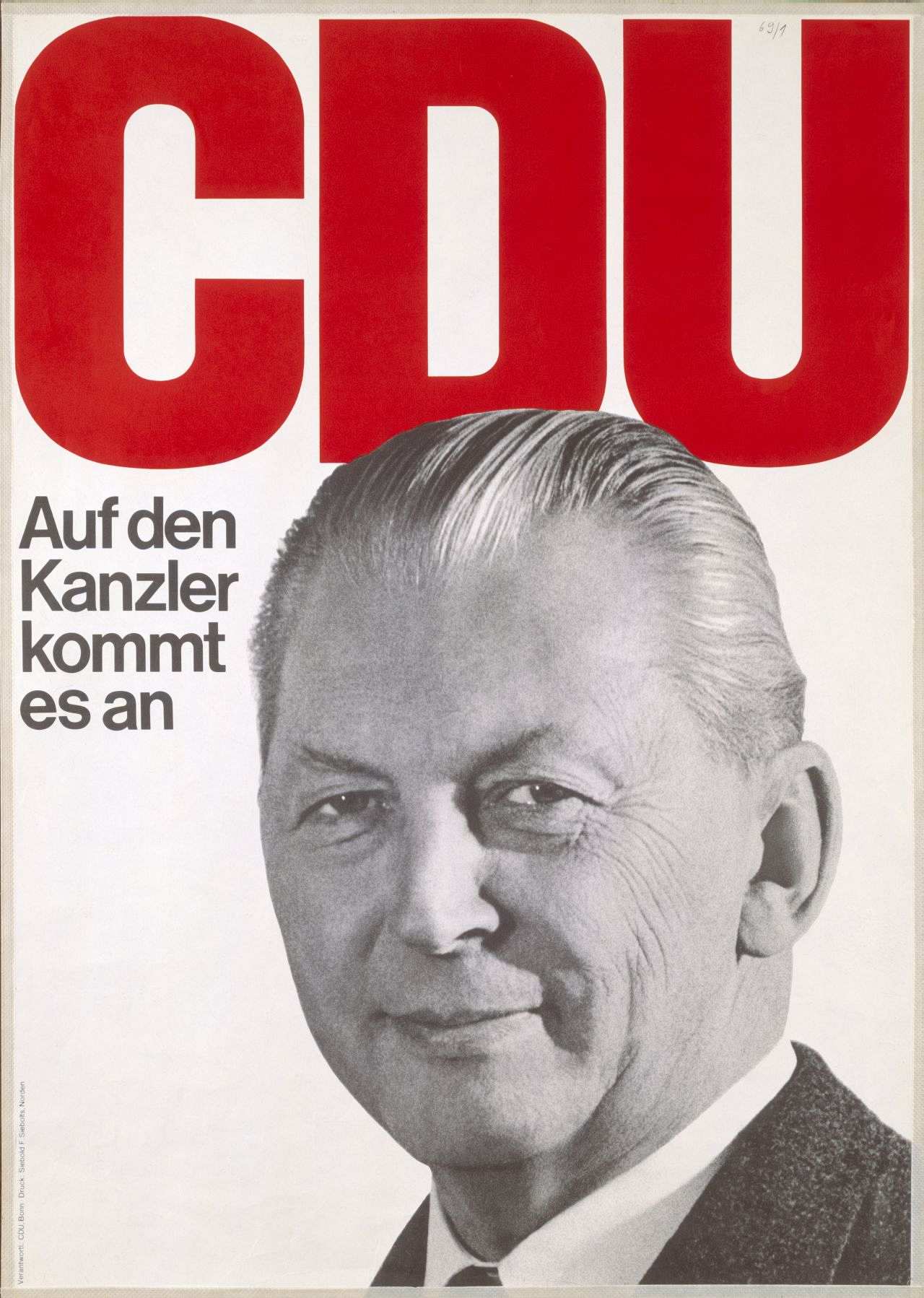

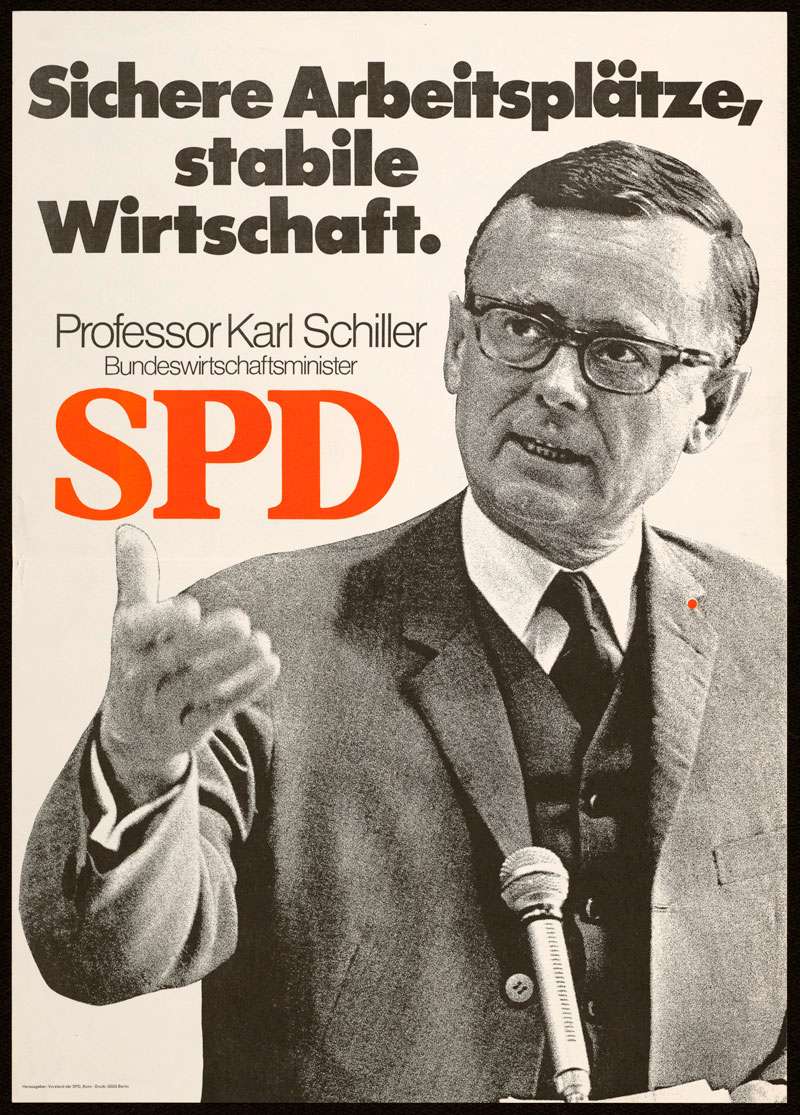

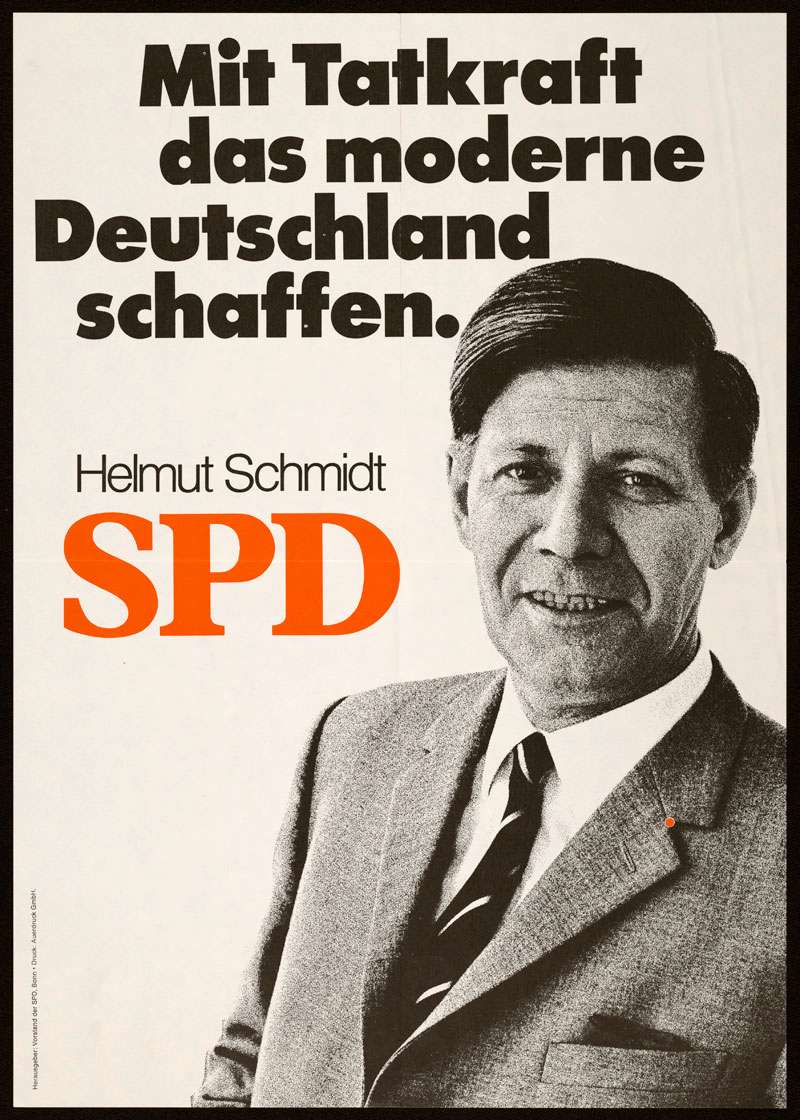

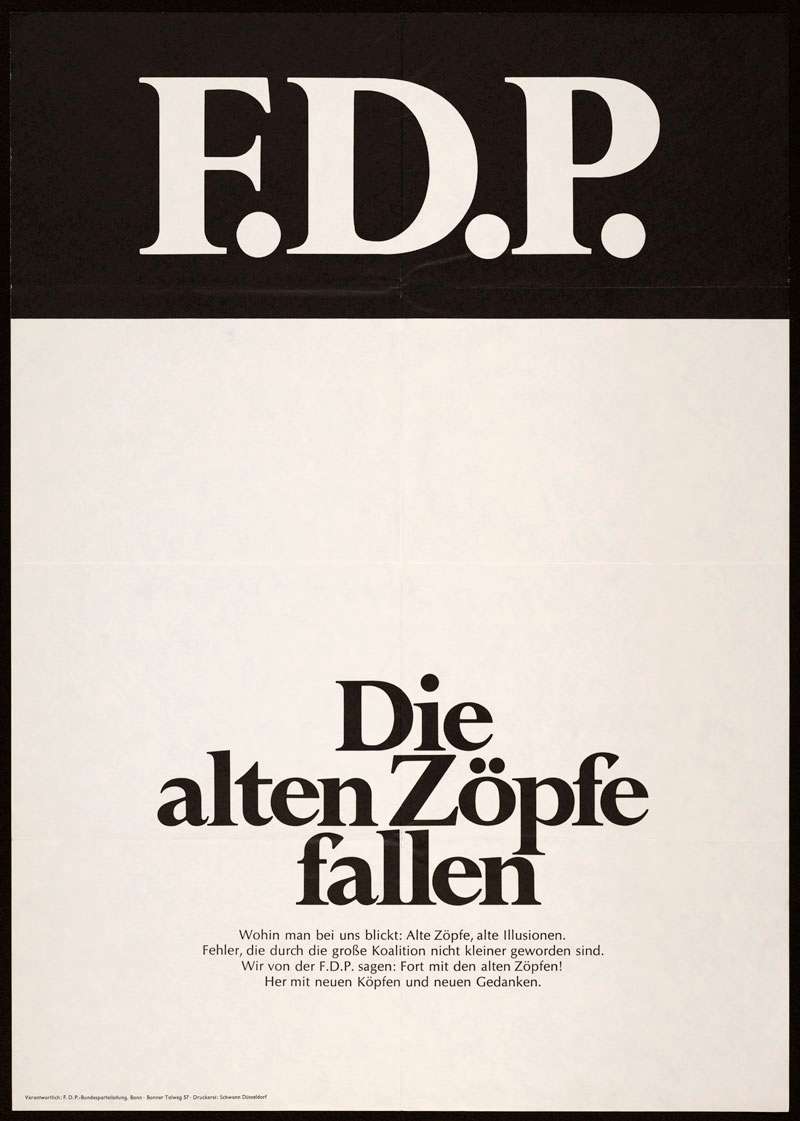

The posters are eerily similar across parties, usually consisting of a party logo, a slogan in Helvetica typeface and a black and white photo of a candidate. Hereby, the conservative CDU mainly points out that they provide the current chancellor Kurt Georg Kiesinger and that he does a good job (which is debatable).

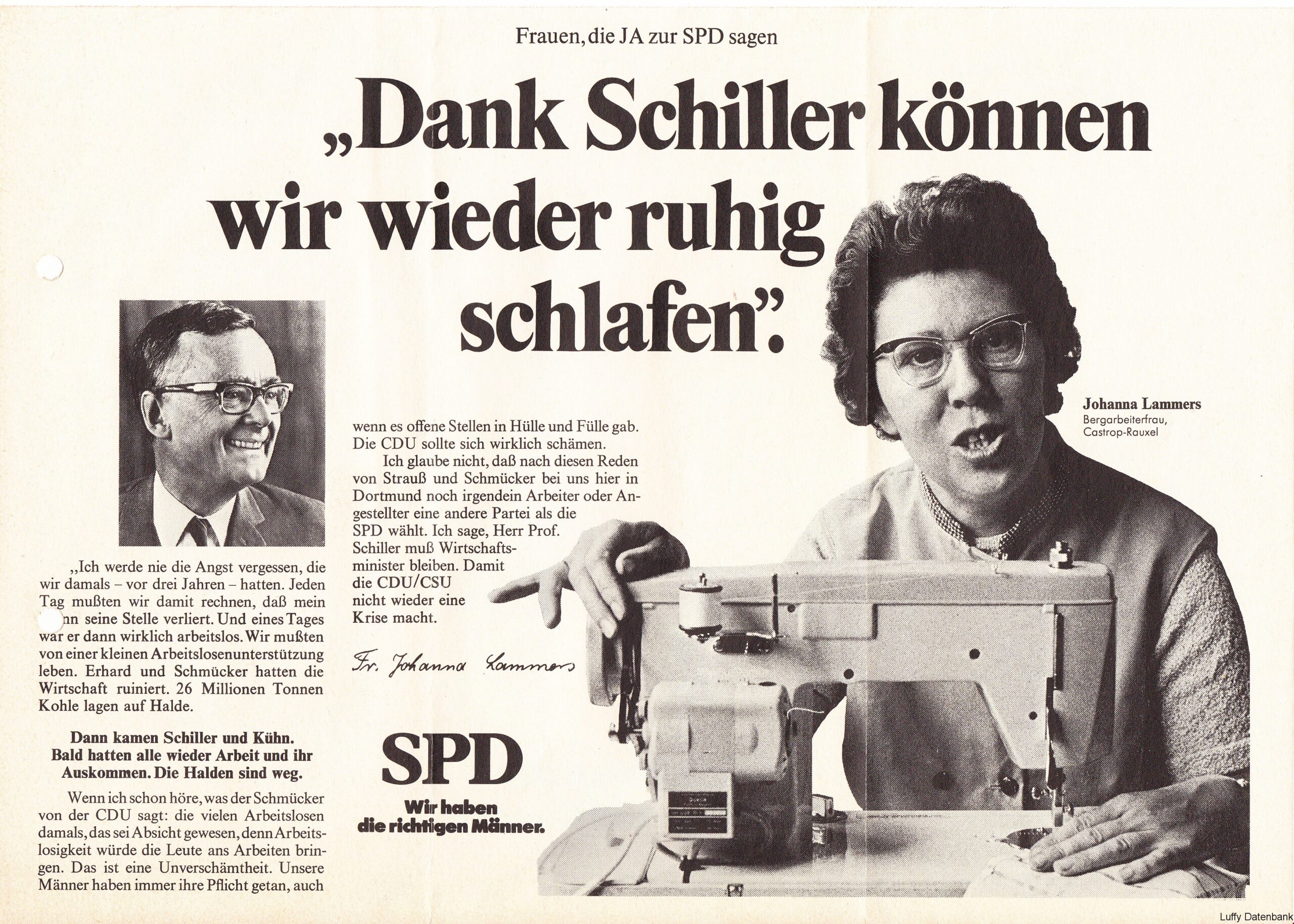

The SPD, meanwhile, has made "For a modern Germany" the focal point of their campaign, though the tagline "We have the right men" made quite a few woman voters grumpy. In response, the SPD launched a campaign where women – both celebrities like actress Inge Meysel and ordinary citizens like Johanna Lammers, miner's wife from Castrop-Rauxel – explain why they vote SPD.

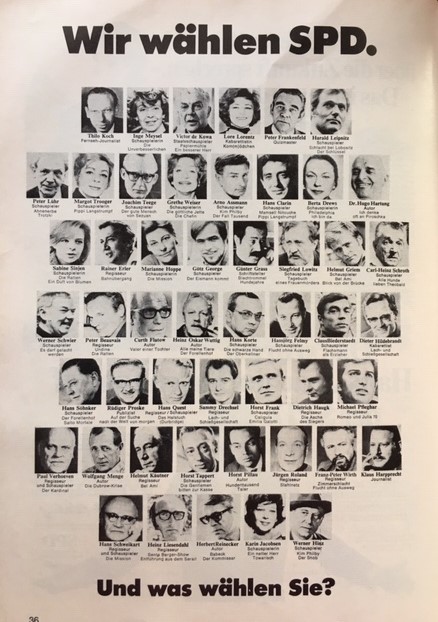

In general, it is notable that the SPD enlisted several celebrities, including writers Günther Grass, Siegfried Lenz and Heinrich Böll, actors Romy Schneider, Götz George, Marianne Hoppe, Sabine Sinjen, Inge Meysel, Horst Frank and Horst Tappert, TV personalities Peter Frankenfeld and Hans-Joachim Kuhlenkampf, directors Victor de Kowa and Wolfgang Menge and singer Katja Ebstein, to campaign for them, something that is common in the US, but almost unheard of in West Germany.

A Small Step

But whatever the outcome of the September 28 election, it's very likely that the current great coalition of the conservative CDU and the social-democratic SPD will not continue.

Due to its large majority, the great coalition actually got a lot done in its three years in office, for better or for worse. Under "for worse", most people would classify the controversial and unpopular emergency powers act, which passed last year – in spite of massive protests.

On the positive side, there is the Great Reform of the Criminal Code, which passed in June and took effect on September 1, which got rid of outdated laws (many of which dated back to the Third Reich or even the Second German Empire) and brought particularly morality related offences more in line with our modern age.

Among other things, adultery is no longer a criminal offence in West Germany. The so-called "Kuppelei" paragraph, which under the guise of combating prostitution forbade landlords from renting apartments and hotels from renting rooms to unmarried couples, and prevented parents from allowing their adult children's boyfriend or girlfriend to sleep over, has been significantly modified.

But most importantly, homosexual relationships between men have been decriminalised, at least if both participants are over twenty-one and there is no employment or service relationship between them. Homosexual prostitution remains illegal.

These are small steps forward, especially since most of the legal limitations applied to homosexual relationships between men do not apply to heterosexual relationships or relationships between women. But they are important steps, because every year between two thousand and three thousand men are tried and convicted for consensual homosexual relationships on the basis of a law dating back to the Second German Empire and significantly tightened by the Nazis.

The end of WWII is often viewed as a liberation, but for homosexual men incarcerated by the Nazis it was anything but, for they remained in prison, while other victims of Nazi persecution were set free. And while the Federal Republic of Germany distanced itself from the Third Reich, it displayed the same zeal in persecuting homosexual men. In 1950, the public prosecution of Frankfurt on Main dragged some 170 men into court on homosexuality charges, based on the questionable statements made by a nineteen-year-old male prostitute named Otto Blankenstein, later revealed to be a notorious liar. Many of the accused were found guilty and jailed, six men committed suicide, others lost their jobs or were forced to flee Germany.

In the light of events such as those that happened in Frankfurt nineteen years ago, the decriminalisation of homosexual relationships between consenting adults is an important step forward. And indeed, the immediate effect of the new law was not the sudden eruption of homosexual orgies in West German streets that conservatives feared but that many men who had been convicted under the old law were set free, because there was no reason to keep them in jail any longer.

More Treasures from the Pulps

But while old and outdated laws are best left behind, older fiction is often ripe for rediscovery. Particularly the pulp magazines of thirty to forty years ago contain many hidden gems and secret treasures just begging to be rediscovered by a new generation of readers. And thanks to the twin success of Lancer's Conan reprints and the Ballantine paperback editions of The Lord of the Rings, many other fantasy works from the first half of the century are coming back into print.

I recently got my hands on two paperbacks reprinting some fantasy gems that until recently could only be found in the crumbling pages of thirty to forty year old copies of Weird Tales.

The enormous success of Lancer's Conan series has also brought other works by Robert E. Howard, either long forgotten or never published at all, back into print. In a previous article, I already took a look at recent reprints of the adventures of Kull of Atlantis, Solomon Kane, and Almuric, as well as Wolfshead, a collection of horror stories by Robert E. Howard. Now another of Howard's heroes from the pages of Weird Tales has made it into paperback form.

The Last King of the Picts: Bran Mak Morn by Robert E. Howard

Nowadays, Robert E. Howard is mainly remembered as the father of what Fritz Leiber called sword and sorcery. However, Howard was also fascinated by history and wrote a lot of historical fiction, with or without fantastic elements. The Bran Mak Morn stories sit on the boundary between fantasy and history. The titular hero is the king of the Picts, a native tribe living in Scotland in ancient times.

Howard was clearly fascinated by the Picts, because they appear throughout his work. The best friend and frequent saviour of Kull of Atlantis is a Pictish warrior named Brule the Spearslayer. The Picts also appear in two Conan stories, "Beyond the Black River" and "The Treasure of Tranicos", where they are portrayed as fierce warriors and sworn enemies of Conan's people, the Cimmerians.

The Bran Mak Morn stories take the Picts out of fantasy and into history, though it must be noted that Howard's Picts bear scant resemblance to what little we know about the actual ancient inhabitants of Scotland. Mostly set in Roman Britain during the second or third century AD, the stories recount the conflict between the technologically superior Roman colonisers and the Picts, who at this point in their history have devolved into Neanderthal-like primitives. Their king Bran Mak Morn knows that his people are doomed, but he is not willing to go down without a fight.

Though the first story in this collection, "The Lost Race", does not feature Bran Mak Morn at all, but instead follows Cororuc, a traveller in Roman Britain, who is captured by Picts and taken to their underground lair. The Picts are described as diminutive – in Howard's time some historians believed they were pygmies – and the likely source of legends about dwarves and little people. They are quite hostile and want to burn Cororuc at the stake – after a history lesson delivered by their chief. But Cororuc's life is spared due to the intercession of a werewolf he'd saved earlier.

"The Lost Race" is one of Robert E. Howard's earliest stories, published in the January 1927 issue of Weird Tales, when Howard was only twenty-one, and is clearly the work of a beginning writer. Three stars.

Bran Mak Morn does appear in "Men of the Shadows", though once again the protagonist is another character, a Norseman who became a Roman citizen and legionnaire. He's part of a squad sent north of Hadrian's Wall on a mysterious mission. The legionnaires are slaughtered in a series of battles with the Picts, until only a handful remain. The survivors try to make it back to safety beyond Hadrian's Wall, but are picked off one by one, until there is only a single survivor who is captured and brought before Bran Mak Morn himself. The Picts want to kill him, but Bran spares his life and also reveals the reason why the legionnaires were sent into Pictish territory, namely because a wealthy Roman had taken a liking to Bran's sister and wanted to take her for his own. Bran's refusal to kill the legionnaire leads to a staring contest between Bran and a Pictish wizard upset that Bran is forgetting the old ways. Bran wins the contest, whereupon the wizard launches into a lengthy explanation of the history of the Picts and also prophesizes the fall of the Roman Empire.

This story was never published in Howard's lifetime and it's easy to see why. It's a disjointed mess and Howard forgets both the plot and even the protagonist, once the wizard launches into the extended history of the Picts. We never even learn what happened to the legionnaire. Perhaps he was bored to death by the lecturing wizard. Two stars.

In "Kings of the Night", Bran Mak Morn is preparing for battle against a Roman legion marching on his land. Bran's Picts have joined forces with Gaels and Britons, but Bran also needs to persuade a group of Norsemen to join the battle. However, their chief has been killed and the Norsemen refuse to fight until they find a new leader. So the Pictish wizard Gonar casts a spell and conjures up none other than Kull of Atlantis, brought forward through time. Kull is understandably confused and mistakes Bran for his Pictish friend Brule the Spearslayer, implying that Bran is a descendent of Brule. However, he also agrees to lead the Norsemen into battle. But is the victory worth the price in blood?

First published in the November 1930 issue of Weird Tales, this is a highly enjoyable story and the return of Kull of Atlantis is most welcome, though it's interesting that Bran outbroods even the traditionally broody Kull. Four stars.

"Worms of the Earth" starts with an incredibly visceral and brutal crucifixion scene. A Pict is executed for killing a Roman merchant who'd swindled him. Presiding over the execution is Titus Sulla, Roman governor of Eboracum (nowadays known better by its British name York), as well as a Pictish emissary. Unbeknownst to the arrogant Sulla, this emissary is none other than Bran Mak Morn in disguise.

Infuriated by the way the Roman colonisers treat his people. Bran vows revenge upon Titus Sulla and he is willing to go to great lengths to get it. And so against the warnings of the wizard Gonar, Bran enlists the aid of the titular worms, the remnants of a pre-human civilisation who may be descendants of the Serpent Men from the Kull stories. But in order to find the worms, Bran first has to consult the witch Atla, who is not entirely human herself, and whose price is nothing less than Bran's virtue. So Bran leans back and thinks of the Picts, while Atla has her way with him.

Bran finally locates the worms and they agree to help him get his revenge on Sulla. But things don't go the way Bran expects…

Published in the November 1932 issue of Weird Tales, this is a great story, which perfectly balances sword and sorcery, history and horror. "Worms of the Earth" is the highlight of this collection and worth the price of admission alone. Five stars.

"The Night of the Wolf" is another story which remained unpublished during Howard's lifetime. Set during Arthurian times, it's the tale of Cormac Mac Art, an Irish reiver who gets embroiled in a conflict between Vikings and Picts in the Shetland Islands, where Cormac tries to negotiate the release of an important prisoner.

"The Night of the Wolf" is a well written story full of action and excitement, but I'm not quite sure why it was included in this collection, because it is not a Bran Mak Morn story, even though the Picts appear. Four stars.

Bran Mak Morn does appear in "The Dark Man", at least after a fashion — because the story is set in the ninth century during the Viking invasion of Ireland, i.e. at a time when Bran is long dead. Instead, he appears in the form of a statue that is worshipped by the surviving descendants of the Picts.

Our hero is an Irish outlaw named Turlogh Dubh O'Brien who's on a mission to rescue his childhood sweetheart Moira, daughter of an Irish chieftain, who was kidnapped by Vikings. Turlogh comes across the statue of Bran and decides to take it along. He crashes the forced wedding of Moira to the Viking chief Thorfel and takes bloody vengeance. The statue of Bran, the titular dark man, comes in handy as well, for where Bran goes, or rather his statue goes, the Picts are not far behind and they are still formidable warriors.

First published in the December 1931 issue of Weird Tales, "The Dark Man" is another fine historical adventure story and unlike "The Night of the Wolf", it has at least some connection to Bran Mak Morn, albeit rather tenuously. Four stars.

I have to admit that I was very eager to finally get my hands on Robert E. Howard's Bran Mak Morn stories. Though I have no Scottish ancestry, I recognise the parallels between Bran and his Picts struggling against Roman rule and the history of my own homeland. For just like the historical Picts, my own ancestors, the Germanic tribes of Northern Germany, managed to kick the Romans out of North Germany and drive them back beyond the Limes Germanicus in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD.

The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest is extremely important to German history. The so-called Hermann Monument near Detmold, a 53 meter tall statue of the Cherusci chieftain Arminius a.k.a. Hermann, is a popular destination for school trips and much beloved. Whenever I'm in the area, I always pay a visit to good old Arminius, even if the statue is not even remotely accurate and the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest most likely did not take place anywhere near Detmold. Archaeologists are still looking for the actual location of the battle

Arminius is to the Germans what the Gaul leader Vercingetorix is to the French, a national hero who fought back against the arrogant Roman invaders. Unlike Vercingetorix, Arminius was victorious and lived to tell the tale. And just like the fictional Bran Mak Morn, Arminius was driven by vengeance, for according to legend he was an officer in the Roman army who turned against his former allies, when the Romans paraded his pregnant wife Thusnelda naked through the streets of Rome in triumph. The veracity of the tale of Thusnelda is debatable, but it is a compelling story and always made me sympathise with Arminius. Bran's story and motivation, though entirely fictional, are just as compelling and I'm sure that Arminius and Bran would find a lot to talk about over a jug of ale or mead.

For all that, the actual collection is a little bit of a letdown. Robert E. Howard just didn't write very many stories about Bran Mak Morn, so Dell topped off the collection with unpublished stories and fragments, poems, juvenilia and vaguely related stories that feature the Picts.

Nonetheless, "Worms of the Earth" is a top tier Howard story and most of the other stories are at the very least entertaining, even if Bran isn't actually in them.

Four stars.

Women's Lib, Sword and Sorcery Style: Jirel of Joiry by C.L. Moore

The yellowing pages of Weird Tales contain treasures beyond the stories of Robert E. Howard and H.P. Lovecraft, whose work Arkham House is doing a good job of keeping in print. One of those treasures that I was extremely excited to get my hands on are the stories C.L. Moore wrote about the medieval French swordswoman Jirel of Joiry. At last the stories are available again for the first time in more than thirty years.

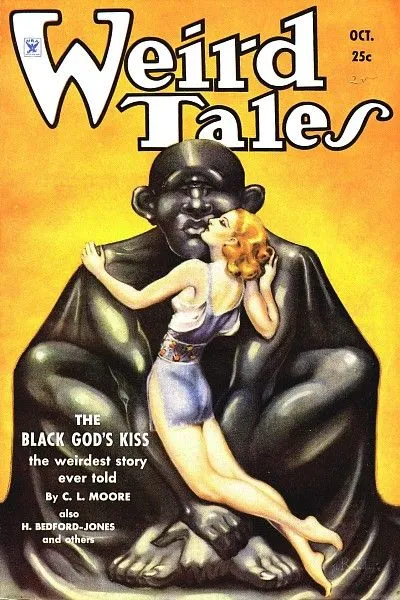

"Black God's Kiss" first appeared in the October 1934 issue of Weird Tales and introduced Jirel of Joiry to the world. The story opens with the iconic and much imitated scene of the warlord Guillaume conquering Castle Joiry. The captured lord of the castle is brought before Guillaume in full armour. When Guillaume orders his captive's helmet removed, the Lord of Castle Joiry is revealed to be a lady, the red-haired firebrand Jirel. Guillaume is quite delighted by this discovery and forces a kiss on Jirel. Jirel is considerably less delighted and tries to bite his throat out.

The revealing of Jirel's gender is an iconic scene and remains impactful even thirty-five years later. I can only imagine how female readers in 1934 reacted to this revelation, even if the surprise was spoiled both by Weird Tales cover artist Margaret Brundage and interior artist H.R. Hammond.

For her troubles, Jirel is thrown into her own dungeon, but she quickly escapes, plotting revenge against the overbearing Guillaume. She has no illusions about what Guillaume will do to her, namely rape her and then either kill her or sell her into slavery. So she goes to see Father Gervase, the resident priest of Castle Joiry, to ask for his help and forgiveness. For in order to avenge herself on Guillaume, Jirel is willing to descend into hell itself. And luckily, there happens to be a passage to the underworld deep beneath the foundations of Castle Joiry. It's interesting how much this scene mirrors the scene in "Worms of the Earth" where Bran Mak Morn plots revenge against Titus Sulla. Both Bran and Jirel are willing to do whatever it takes, even if it means selling their soul (and in Bran's case, his body) and enlisting demonic aid. And in both cases, their spiritual advisors, respectively Gonar or Gervase, strongly advice against this course of action, noting that some weapons are too terrible to use.

Like Bran, however, Jirel is determined and so she descends into the underworld beneath the castle. The bulk of the story is given over to Jirel's journey through the underworld and the fantastic things she encounters there. It is notable that even though Jirel wears a crucifix which she has to discard in order to enter the underworld and has a theological argument with a Catholic priest earlier in the story, the dreamlike land underneath Castle Joiry does not resemble the traditional Christian depictions of hell in the slightest—it is much stranger.

Jirel finally finds the titular black god in a temple in the middle of a lake of fallen stars and begs him to give her a weapon against Guillaume. The black gods grants her this wish, but just like Bran Mak Morn in "Worms of the Earth", Jirel realises that the revenge she gets isn't what she wanted after all.

This is an amazing story that stands shoulder to shoulder with the best the sword and sorcery genre has to offer. Five stars.

Only two months later, in the December 1934 issue, Weird Tales published the sequel to "Black God's Kiss" entitled "Black God's Shadow". Jirel is still haunted by the events of the previous story. She's having trouble sleeping, the memories of Guillaume forcing a kiss on her keep resurfacing and by night, Jirel hears Guillaume's voice, begging her to save his soul from hell.

Jirel's feelings towards Guillaume are very conflicted. On the one hand, he was an overbearing pig who assaulted her, but on the other hand Jirel was also attracted to him. So she decides to descend into the underworld once more to save Guillaume's soul. But in doing so, Jirel will not only have to fight the black god, but also her own conflicted emotions and come to terms with what happened to her.

This story is more quiet and philosophical than its predecessor and the battles Jirel fights are purely in her mind. From a psychological standpoint, this story is fascinating, because Jirel's feelings and reactions mirror those of women who have been sexually assaulted or raped, suggesting that Guillaume did more than merely steal a kiss.

An unusual but excellent story. Five stars.

"Jirel Meets Magic" first appeared in the July 1935 issue of Weird Tales. The title is rather weak, especially since Jirel already encountered more than her share of magic in her first two adventures.

The story opens with Jirel leading the charge against a castle, whence the evil wizard Giraud has fled. Once again, the hotblooded Jirel is out for vengeance, because Giraud had ambushed and killed some of her men. However, as Jirel and her men comb the castle, Giraud is nowhere to be found. Bloody footprints lead to a window, which doubles as a portal into a fantastic world. Undeterred, Jirel climbs through the window in pursuit of Giraud and quickly finds herself tangling not just with the wizard, but also with his patroness, the sorceress Jarisme.

This story establishes what will become a pattern with the Jirel of Joiry stories, namely that Jirel keeps venturing into fantastic dream landscapes. "Jirel Meets Magic" is not quite as dark as the Black God duology, but still a great story. Five stars.

"The Dark Land" opens with Jirel lying in bed in her castle, mortally wounded in battle. Father Gervase is called in to give her the last rites, when Jirel abruptly vanishes. When she comes to, she finds herself in yet another fantastic dreamland called Romne. Its king Pav informs Jirel that he saved her from death, because he wants her to be his bride. Jirel has other ideas, especially once she learns what happens to Pav's discarded wives…

Published in the January 1936 issue of Weird Tales, this is a good story, but not quite as strong as the previous tales. Four stars.

"Hellsgarde" opens with Jirel on her warhorse outside the haunted castle of Hellsgarde. The castle, we learn, has been shunned and abandoned for two hundred years, ever since its previous lord stole a mysterious treasure and was tortured to death by those eager to take that treasure for themselves.

Jirel has come to Hellsgarde for just this treasure, though she doesn't want it for herself. No, a villainous nobleman named Guy of Garlot has taken several of Jirel's men hostage and demands the treasure of Hellsgarde as ransom.

As the previous stories have shown, Jirel is perfectly willing to descend into hell itself and so she enters the haunted castle to face of the horrors awaiting her within. As for Guy of Garlot, he fares about as well as all overbearing men who try to force Jirel to do something against her will.

First published in the April 1939 issue of Weird Tales, "Hellsgarde" is a very much a haunted house story, but what a haunted house story it is. Five stars.

Reading the Jirel of Joiry stories in the year of the lord 1969, it's hard to image that these stories are already more than thirty years old, because they feel so very modern, both with regard to Jirel's adventures in psychedelic dreamlands and her conflicts with overbearing men which many a modern feminist will sympathise with. Jirel is very much a heroine for the 1960s, a strong woman willing to brave even hell itself to get what she wants.

C.L. Moore only ever wrote six stories about Jirel of Joiry (one of which, a story featuring Jirel and Moore's interplanetary outlaw Northwest Smith, is not included in this collection) and sadly retired from writing altogether after the untimely death of her husband Henry Kuttner eleven years ago. However, the Jirel stories are so good that I hope that Moore will eventually return to writing and revisit this groundbreaking character.

If you are looking for the two-fisted adventures of Conan or the hijinks of Fafhrd and Gray Mouser, this collection is very much not that. Jirel's adventures are internal conflicts given form in her journey through dreamlike and often nightmarish landscapes. Nonetheless, these stories are among the best the sword and sorcery genre has to offer. Five stars.

![[September 14, 1969] More Gems from the Pulps: <i>Bran Mak Morn</i> by Robert E. Howard and <i>Jirel of Joiry</i> by C.L. Moore](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/690914coracovers-601x372.jpg)

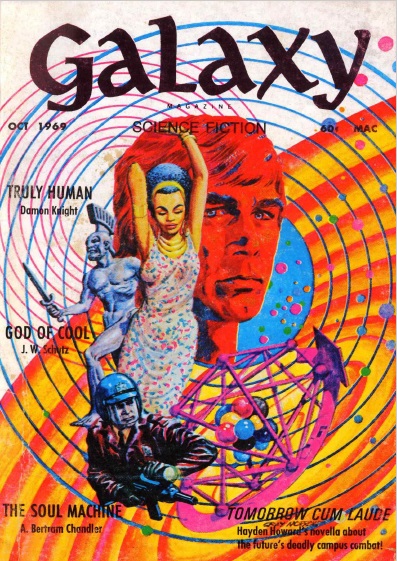

![[September 12, 1969] Earthshaking (October 1969 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/690912galaxycover-397x372.jpg)

![[September 10, 1969] Once Upon a Time in the West: Best Film of the 1960s?](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/west-title-672x372.jpg)

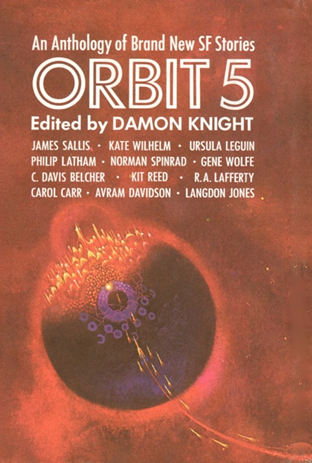

![[September 8, 1969] Another Orbit around the sun (<i>Orbit 5</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/O5-3-312x372.png)

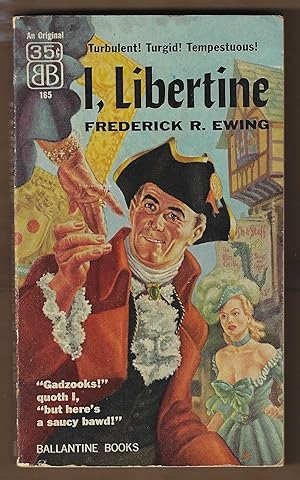

![[September 6, 1969] A hot time in the old town (Worldcon in St. Louis!)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/690904book-603x372.jpg)

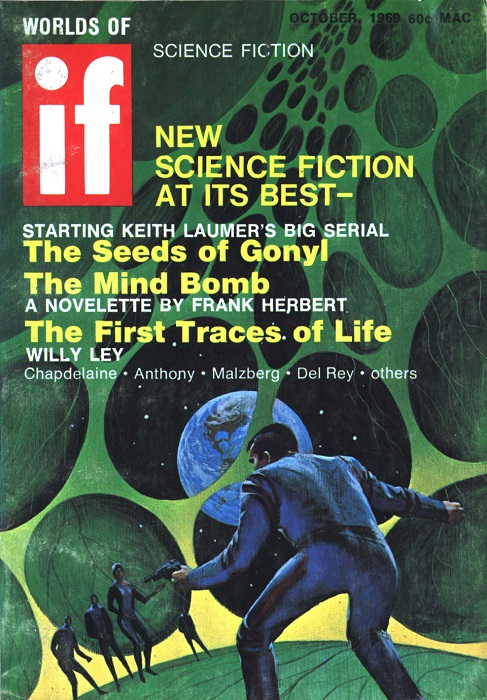

![[September 4, 1969] <i>Plus ça change</i> (October 1969 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/IF-1969-10-Cover-487x372.jpg)

Penelope Ashe, in part, with the cover model superimposed.

Penelope Ashe, in part, with the cover model superimposed.

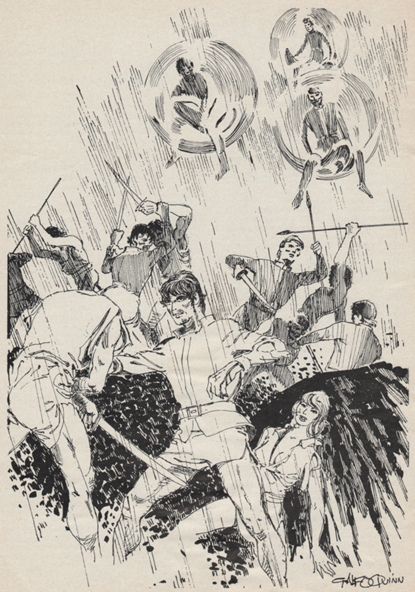

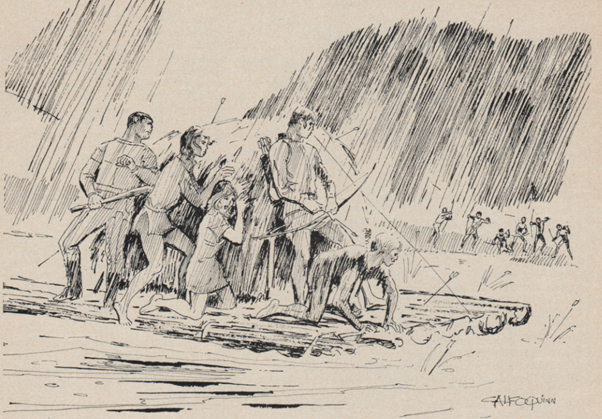

Supposedly for Seeds of Gonyl. If so, it’s from later in the novel. Art by Gaughan

Supposedly for Seeds of Gonyl. If so, it’s from later in the novel. Art by Gaughan![[September 2, 1969] People, Machines, and Other Thinking Entities (October 1969 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/COVERSMALL-672x372.jpg)

![[August 31, 1969] Over (and under) the Moon (September 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/690831analogcover-659x372.jpg)

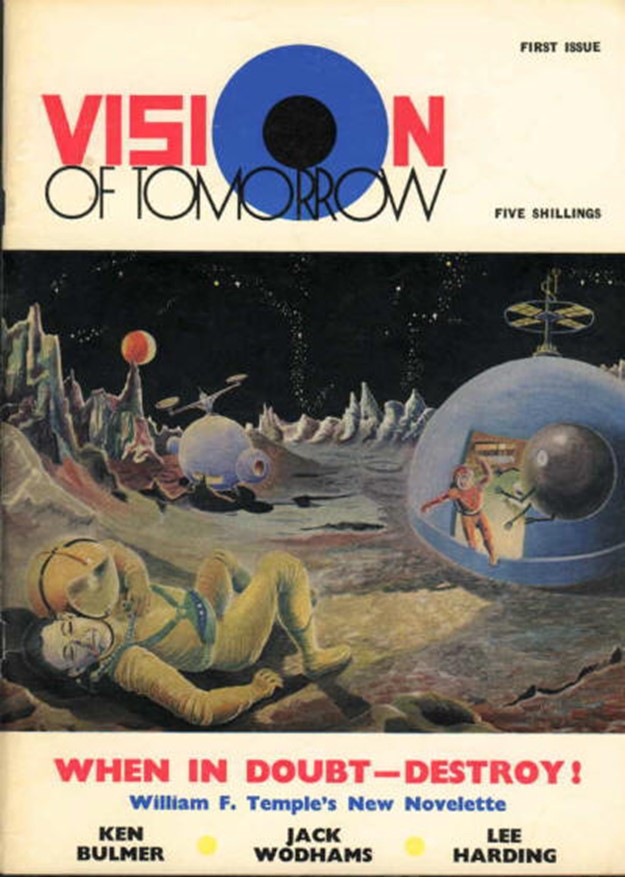

![[August 28, 1969] Aussie-British Publishing (<i>Vision of Tomorrow #1</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/VOT2-625x372.jpg)

![[August 26, 1969] A Bumper Crop at the Farm (Woodstock Music & Art Fair)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/900_woodstock1_1663012591.3295-672x372.jpg)