[For this exciting occasion, we've put together the reactions of several of the Journey team as well as a new phace…er…face! Come join us as we recount our experiences with this exciting new science fiction epic called Star Trek…]

by Gideon Marcus

Where No Show Has Gone Before

Last night marked an exciting new day in science fiction: the debut of a new science fiction anthology.

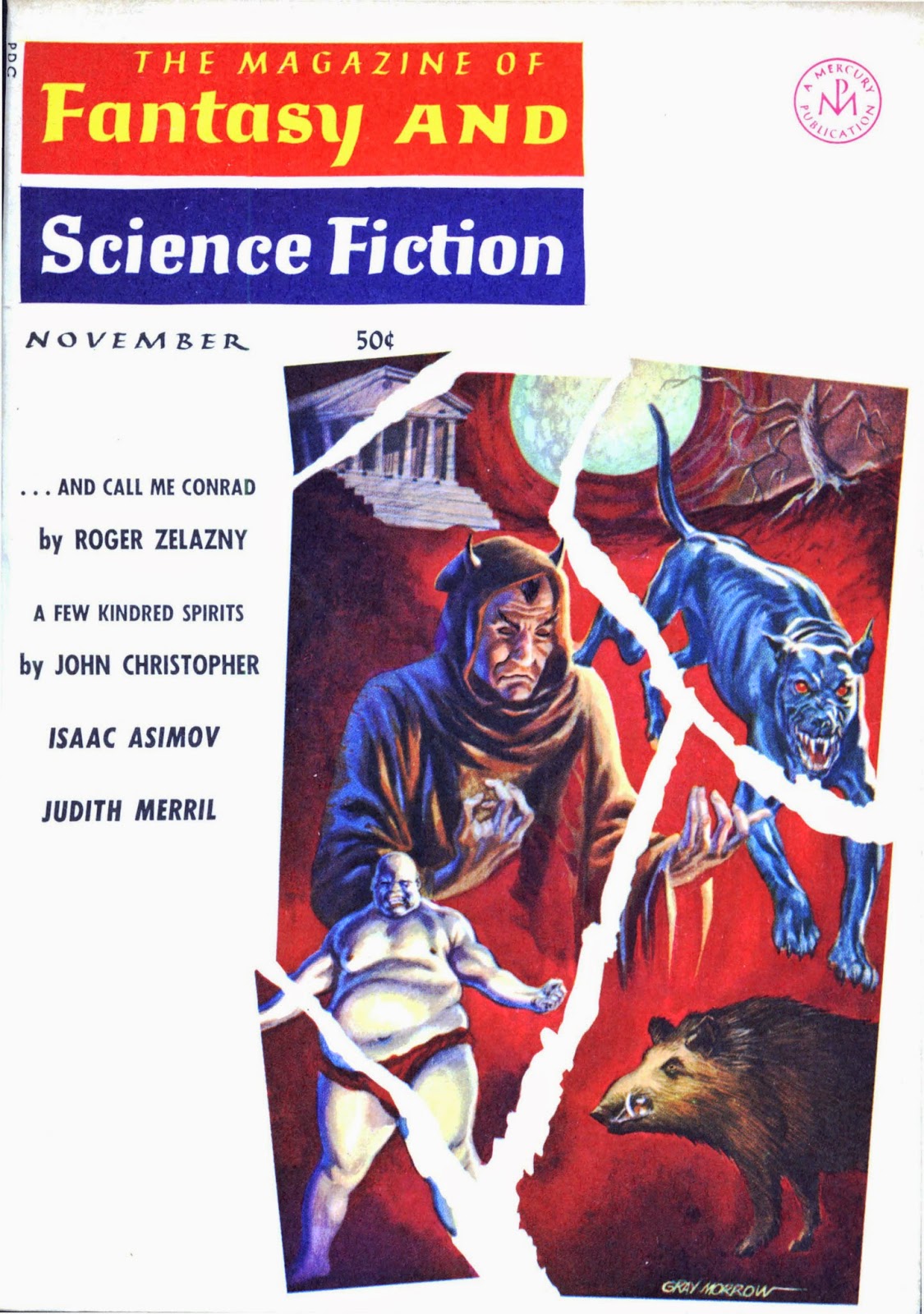

Science fiction on television has always been kind of a backwards sibling to science fiction in print. While there have been entertaining and even thoughtful episodes of The Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits, for the most part TV SF has been some of the worst schlock. Stories that wouldn't have been accepted in third-rate mags in the 50s. Shows like Lost in Space, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, and My Favorite Martian — kiddified frivolity with zap guns and giant monsters. Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon serials with inserts for soap commercials.

We fans had an inkling this new show would be something different pretty early on. Its producer, Gene Roddenberry, previously put out an interesting, mature show about a Marine Lieutenant called…The Lieutenant. At Westercon, one of the Star Trek pilots was previewed over the 4th of July weekend to much acclaim (we missed it as we had planned a birthday celebration at our house just 20 miles away from the convention!) There have been promo spots on NBC pitching the show, plus promotional pictures and coverage in both conventional newspapers and news 'zines. They were all quite compelling.

At Tricon, I got my first direct glimpse of the beast. The last two days of the convention, Roddenberry showed the two pilots to the show. I left the convention both hopeful and concerned.

You see, the first pilot, "The Cage", was a masterpiece. Without hyperbole, it was probably the best science fiction made for a screen (of any size) as of 1964. Brilliantly written, scored, special-effected, and directed (if just competently acted), it was also daringly progressive. Women were on equal footing with men, something I rarely see even in written science fiction these days. There were no villains, per se, merely beings resorting to desperate measures to save themselves. Call it Forbidden Planet but done right.

"The Cage" was rejected, I don't know why. Too expensive, perhaps, or maybe too cerebral. But it was liked enough that a second pilot was greenlit. "Where No Man Has Gone Before" was the result.

It was a disappointment.

The beautiful sets and cinematography were gone, the cheap result looking like an episode of Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea. We had a new actor in the role of captain, and while I didn't think Jeffrey Hunter stretched himself much in "The Cage", William Shatner, on the other hand, was a contortionist, playing every scene to the maximum. To be fair, he was new to the character, and the script did him few favors, shedding little insight into the character. John Hoyt, who did a lovely job as the ship's doctor in "The Cage", was replaced by a non-entity. Indeed, the only consistent cast member was Leonard Nimoy as the oddly strident "Mr. Spock", who in the second pilot, was reduced to something of a "wise Indian" role.

With pacing issues and a rather thin story, "Where No Man” augured poorly for the show, especially since it seemed more indicative of what we were going to get.

Still, a dozen or so of us gathered around our 25" color Admiral for the TV premiere of the show, set for 8:30 PM on September 8. We'd set up a signal with our friends on the East Coast, since they got to watch it three hours before us: If the show was a stinker, at 6:30 our time, they'd phone us, letting the line ring once. If the show was good, they'd ring twice. (We wouldn't actually pick up the phone — long distance calls, especially during prime time, are prohibitively expensive).

As we ate our dinner, the jangle of the telephone made us jump. What would be the verdict? The bells chimed once. We waited with bated breath. Then a second ring. Then silence. We grinned at each other.

And so, we sat through the latter half of Tarzan (also debuting on NBC that night). At 8:30 PM, the main event began.

In brief: the spaceship Enterprise is paying a visit to the planet M113 to conduct an annual medical check-up of scientific personnel based there. The only residents of the barren world are an archaeologist man-and-wife pair, the latter of whom was the old flame of the Enterprise's third medical officer in as many episodes. Said woman appears to each member of the ship's landing party in a different form, some kind of telepathic camouflage.

Said woman is also a killer, stalking humans individually and then draining them of their salt. She ends up aboard the Enterprise, changing forms and continuing her deadly hunt.

On the face of it, it's a stupid plot. The biology seems nonsensical, and Lord knows we've had enough monster plots on Voyage and The Outer Limits. And yet…

"The Man Trap" is beautifully put together. It's not quite "The Cage", but it's definitely not "Where No Man". The Enterprise is a somberly lit, "lived-in" vessel with hundreds of crew. For the first time, I had the impression of a real space-going vessel. I appreciated that the Enterprise appears to be the equivalent of a Hornblower-era frigate, a second-line vessel doing routine business around the galaxy. I quite like Forester's series, and given the youth of the ship's captain, the Hornblower analogy might be extended.

The three main actors, Shatner, Nimoy, and newcomer DeForest Kelley, were excellent, settled, and even understated in their roles. The supporting cast was quite good, too. George Takei, who I'd just seen in the Cary Grant flick, Walk, Don't Run, and in a couple of episodes of I, Spy, turns in a particularly pleasant, if brief, performance. Gone was the powerful woman first officer of "The Cage", but we did get a Black woman bridge officer named Lt. Uhura. So daring was this casting choice that there was some fear that she would be one of the victims of the episode's monster!

The special effects are quite masterful, from the superb optical effects of the ship orbiting the planet, to the shimmering fade out/in of the "transporter" (which beams people from the Enterprise to planetary destinations), to the blast of the phaser (no longer laser) guns.

Verdict: Star Trek is back on course. With two out of three episodes being excellent, I've got confidence that this is a show that will reward consistent viewing. You can bet we'll all gather together again next Thursday.

Rating for "The Cage": 5 stars.

Rating for "Where No Man has Gone Before": 2.5 stars.

Rating for "The Man Trap": 4 stars.

Thoughts from Galactic Journey’s editor:

by Janice L. Newman

The traveler has already said most of what I would have written about (I was the one saying, “I hope they don’t kill her off!” when Lt. Uhura was being menaced by the creature). A few additional thoughts about last night’s episode:

The cinematography was impressive. When the crew encounter the creature in the first act and each crewmember sees it as a different woman, this was done so smoothly and seamlessly that there was never any question which person’s POV we were following.

The story was nuanced. Though this was a ‘kill the monster’ story, the morality of killing a creature that is ‘the last of its kind’ is called into question, with comparisons being made to the American buffalo and the passenger pigeon. It adds to the story’s poignancy, and the viewer is left wondering whether it might have been possible to resolve the situation without deaths on either side.

Particularly exciting was seeing women in interesting roles, though their ‘uniforms’ were VERY short! I wonder why the men don’t wear short tunic and pantyhose combinations like that?

Rating for "The Cage": 4.5 stars.

Rating for "Where No Man has Gone Before": 2.5 stars.

Rating for "The Man Trap": 4 stars.

A Hippie's Opinion

by Erica Frank

Star Trek has certainly been interesting so far — even "fascinating," as Mr. Spock might say. The ship's controls seem complex but plausible: none of the "three dials and a lever" that plague cheap movie productions, and yet each console seems within the range of a trained technician's skills. Lt. Uhura even mentions being momentarily fed up with her desk work, a nice bit of "office life" banter as she tries — unsuccessfully — to flirt with Mr. Spock.

However, the Star Trek universe is showing signs of predictability. None of it is bad, so far, but if it's going to last, it'll need more variety in its settings and plots. It won't take long for these themes to become clichés.

Three rocky, dusty desert planets.

Three hostile encounters with beings with psychic powers.

Three doctors. The Enterprise seems to go through them like some rock bands go through drummers.

The psychic elements of the creature in "The Man Trap" were minimized; the focus was (understandably) on the creature's murderous habits. However, its "shape-shifting" was actually a kind of mental illusion, although more limited than we saw in "The Cage." And the fact that its victims could not rally themselves to escape, even when called, showed some kind of mind control ability that the Talosians and Mitchell both lacked.

My favorite scene in the episode: Professor Crater showed Kirk and McCoy his dwindling supply of salt, and said, "Nancy and I started with 25 pounds. This is what we have left." McCoy took a few tablets from the nearly-empty vase and tasted one. "Salt," he declared.

Dr. McCoy tastes the "salt"

This is exactly how hippies get cops to take LSD, although they normally put it on sugar cubes, not salt tablets. (LSD has no color or flavor; the active elements are too small for people to taste.) I spent the next several minutes waiting for the hallucinations to kick in.

The producers could've given us a wild psychedelic color extravaganza instead of four more murders. I think we've been cheated.

I don't mind "psychic powers can make people callous or predatory" stories; they're a science fiction staple. I'm hoping we also get some episodes where extra-sensory perceptions lead to more harmonious communities or solve problems instead of creating them.

I enjoyed the episode despite a bit of hand-waving past some plot details. (For example, tasting the salt instead of using a science lab to confirm its identity. The result would've been the same, and this saved time.) The acting was great; I believed these were starship personnel facing a citizen who'd allied himself with a hostile alien. I'm looking forward to more of the series.

4 stars.

Who the %&@$ is Captain Kirk?

This first episode didn't give me a good idea of who Kirk is or what his past is, even though I'm pretty sure Kirk is supposed to be the main character of the show. (This is something I also felt was an issue with "Where No Man Has Gone Before".) "The Man Trap" centered more around McCoy, which is fine – I like the implication that with each new episode, a different member of the crew will be at the center of the plot – but for a first episode of a show, I wish they'd spent a little more time getting the audience acquainted with Kirk. When Kirk's life was threatened, I didn't feel any tension since I knew they weren't going to kill him off in the first episode, and his being captain isn't enough for me to root for him.

Pike, the captain in “The Cage”, was better established as a character in the first 20 minutes of his episode than Kirk was in both his pilot and the first episode combined. We know Pike is tired. We know he’s considering retiring. We know he’s from Earth. Kirk? I don’t know anything about him besides his pretty face.

I am left more frustrated than intrigued about his character. Why should I care about the success of this man if I don’t know who he is or what he’s about?

The good story alone in “The Man Trap” convinces me to give this new captain a chance, though I hope the lack of Kirk’s background is something that is remedied sooner rather than later.

This is a great episode, but not a good introduction. 5 stars, despite my complaints.

Home Town Hero

by Tam Phan (Secret Asian Man)

“The Man Trap” is a refreshing debut after the whiplash that resulted from starting with “The Cage” and going straight to “Where No Man Has Gone Before”. In the first few minutes of the episode, we’ve already seen clever camera work, stunning special effects, and a pleasantly paced plot.

It’s a bit concerning that we, yet again, have a new doctor, though I did like his friendship with Kirk, echoing the relationship of Pike and Boyce from "The Cage". The two recurring characters, Kirk and Spock, seem to be the only staple in the show thus far, but perhaps the continued diversity of the cast will prove to be an asset. This is an anthology show, after all.

Seeing Lieutenant Sulu, played by Asian actor George Takei, is nothing short of inspiring. He didn’t contribute much to the plot, but he was an officer with clear officer duties and that is not inconsequential. With at least as many scenes as any of the other supporting actors, I suspect that means the “green thumbed” lieutenant will be a highlight of the show in the upcoming episodes.

Hopefully this show continues to impress. It would be a shame to fall back down after such a great start, but we won’t know until next week.

Rating for “The Cage”: 5 stars

Rating for “Where No Man Has Gone Before”: 2 stars

Rating for “The Man Trap”: 4 stars

From the Young Traveler

by Lorelei Marcus

"Man Trap", though a moodier tale than what I usually prefer, executes every piece of the episode in a superb manner: the acting, direction, and production are all 5-star quality.

Rarely have I seen such a diverse, well-written, and interesting show on television — Star Trek is truly the I, Spy of the science fiction genre (is it any surprise both are Desilu productions?)

It's definitely getting HI-LITED in my TV Guide!

5 stars for this episodes, and high hopes for what's to come.

(And don't forget to tune in in three days at 8:30 PM (Pacific AND Eastern — two showings) for the next episode of Star Trek!)

![[September 12, 1966] Boldly Going (<i>Star Trek</i>'s "The Man Trap")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/660914title-672x372.jpg)

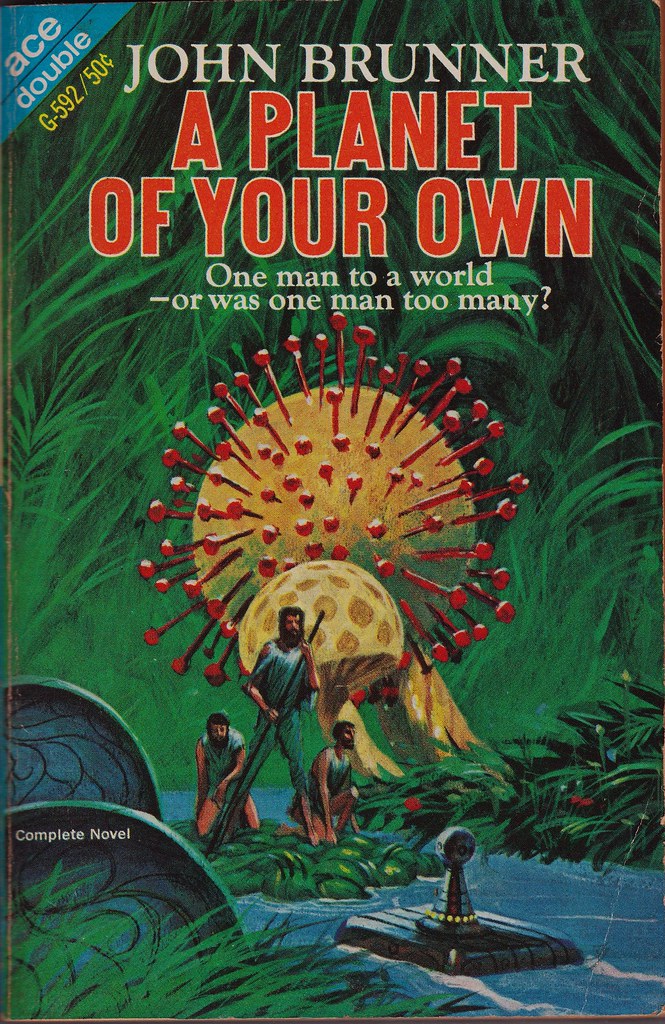

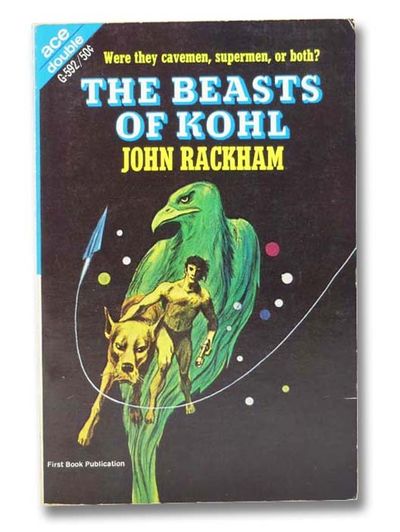

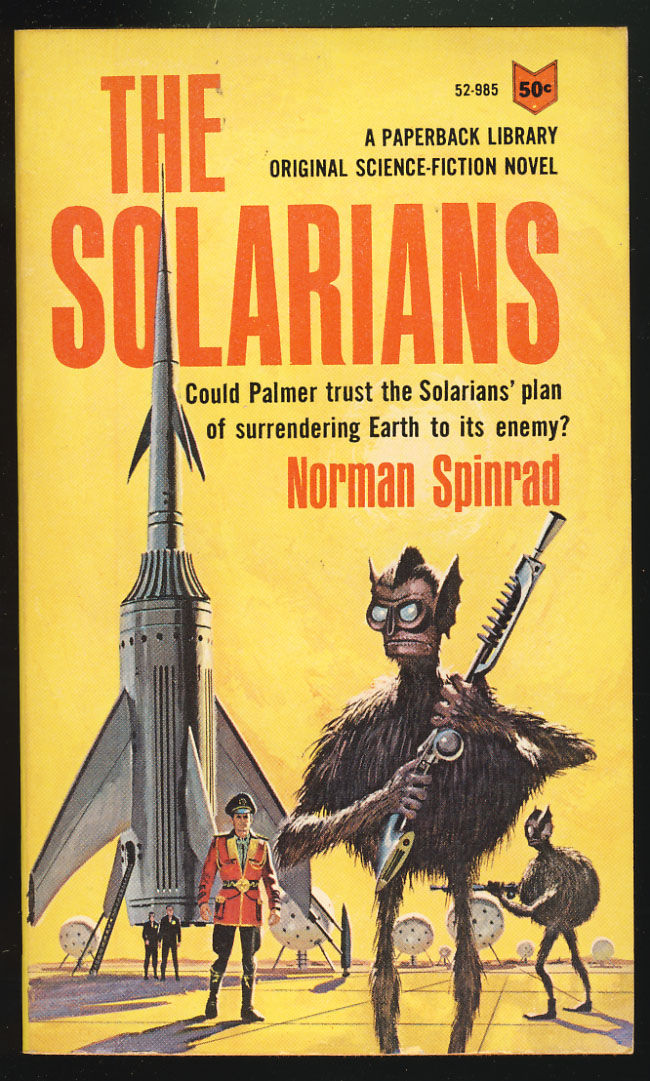

![[September 10, 1966] Bon appetit! (this month's Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/660910covers-672x372.jpg)

![[September 8, 1966] The Bare Hardly-Essentials (October 1966 <i>Amazing</i>)</big></b>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/amz-1066-cover-491x372.png)

![[September 4, 1966] British Science Fiction Lives! (Alien Worlds #1 & New Writings in SF #9)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Featured-Image.jpg)

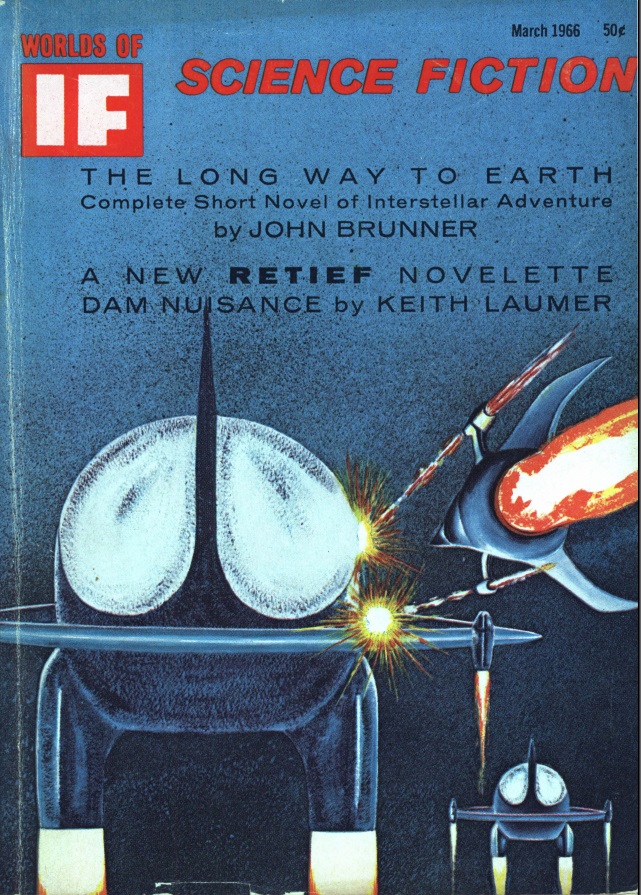

![[September 2, 1966] On the Edge (October 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/IF-1966-10-Cover-662x372.jpg)

![[August 28, 1966] Messiahs and Resignation (<i>New Worlds</i> and <i>SF Impulse</i>, September 1966)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/New-Worlds-SF-Impulse-Sept-1966-672x372.jpg)

![[August 24, 1966] Fantastic Voyage lives up to its name!](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/t9MuMN1-672x372.jpg)

![[August 20, 1966] Looking forward, looking back (September 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/660820cover-672x372.jpg)