by Alison Scott

Something is rotten in the science fiction fandom community. And its name is Pong.

I recently came into correspondence with Gideon Marcus, founder of Galactic Journey. I took him to task for the lack of fanzine reviews and commentary in his ‘zine–a shocker in such an otherwise comprehensive overview of our modern world of science fiction. He suggested that there was an obvious remedy to that omission. And so, I find myself dragooned into the position of “Associate Writer” for the Journey. You’re welcome.

Although I’m based in London, I’m fortunate enough to trade with many fan editors around the world, and hope to share with you some of the topics that are exciting fans this summer, and that are mentioned in the fanzines arriving in the post each day. And one topic,in particular, has consumed the thoughts of SF fans across the globe–the idea that the fan Hugos will be separated from the “real” Hugos and given their own name.

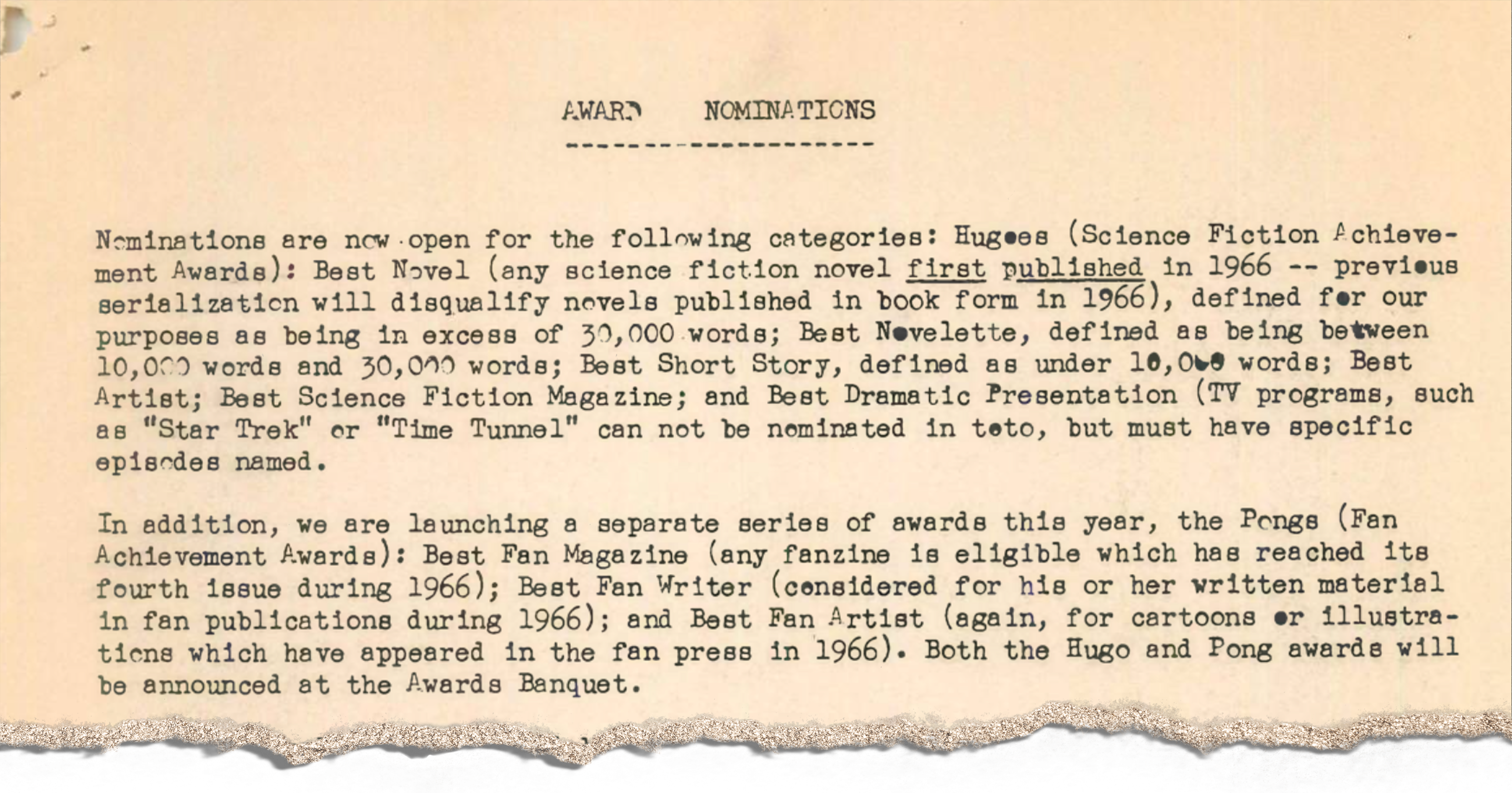

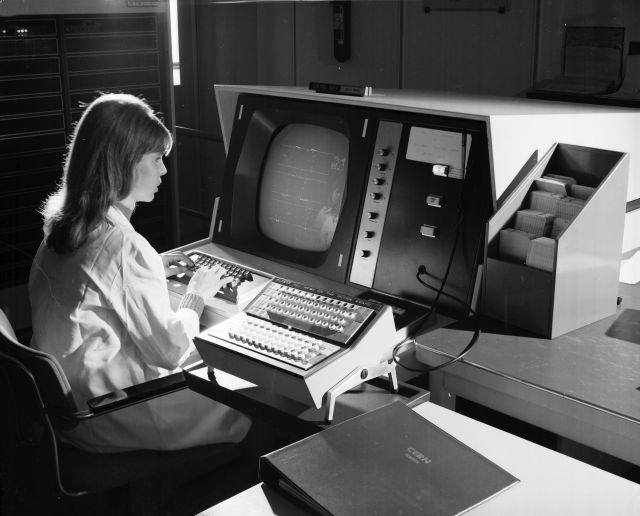

A section of the Hugo Award Nomination ballot for 1967, with a torn paper edge at the base.

Tucker’s Folly

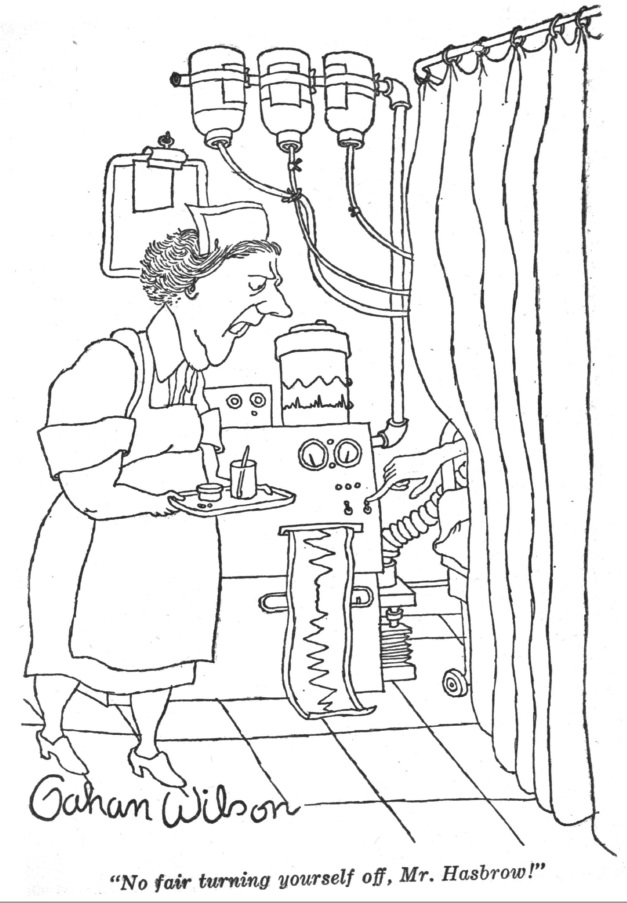

How many of you remember Hoy Ping Pong? I am not sure how familiar that name will be to the readers of the Journey. Hoy Ping Pong – “The Chinese Buck Rogers” – was a pseudonym used by Wilson ‘Bob’ Tucker in the 30s and 40s for much of his humorous fan writing, such as his “Report of the 196th Convention”, which you can read as a featured letter in Wonder Stories, November 1934, if you can find a copy. Tucker dressed up as Pong for the first convention masquerade at Chicon in 1940, though I have been unable to find a photo of this event. Over the years there have been many occasions in which Tucker appeared in place of Pong, or where Tucker wrote an appreciation of Pong or vice versa. Japes of this kind were commonplace amongst early fans. And in Tucker's case, as appreciated (or not appreciated, depending on who you ask) as the Chinese characters we keep seeing being played by British actors in Doctor Who. [or Mickey Rooney's turn as Yunioshi in Breakfast at Tiffany's (ed.)].

Tucker will perhaps be best known to Fellow Travelers as an author and critic. Perhaps one of you has found your name “Tuckerised” as a character in one of his sadly infrequent novels. But those of us who follow fanzines will know that he is one of the very first and most energetic fanzine fans, and instrumental in the flourishing of fanzines and therefore of science fiction fandom itself. Sadly, Tucker has not published an issue of his fanzine, Le Zombie, since 1958. And so therefore (perhaps not so sadly) we have not seen so many outings for Hoy Ping Pong, or any other of Bob Tucker’s Pong-based pseudonyms, such as John W Pong Jr and Horatio Alger Pong. And as such, they are drifting into obscurity.

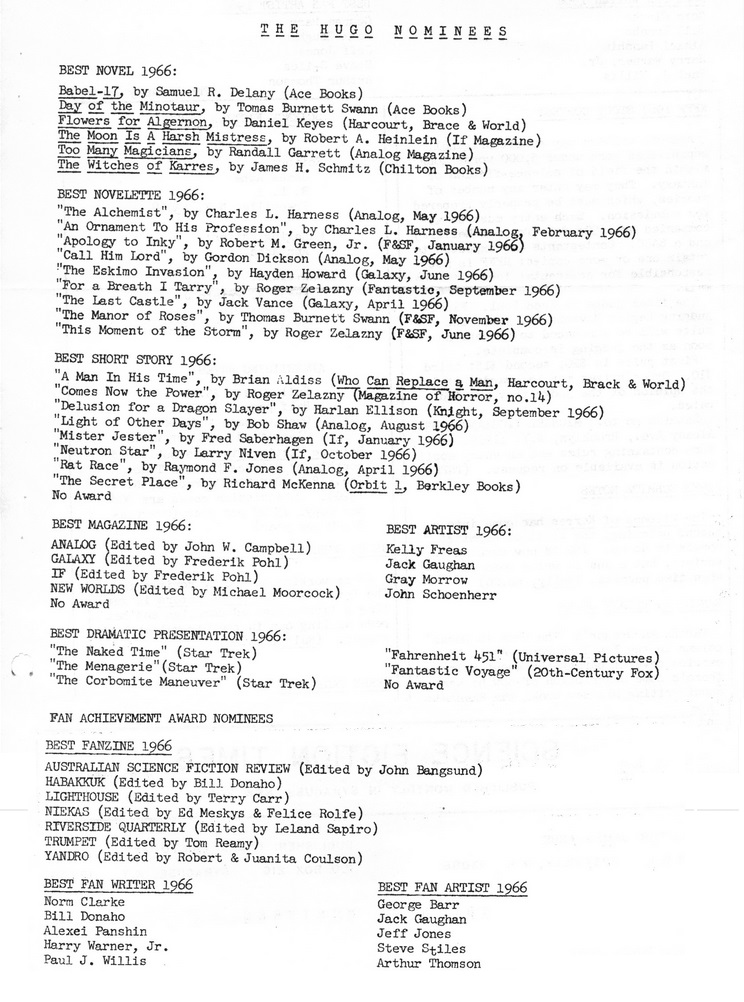

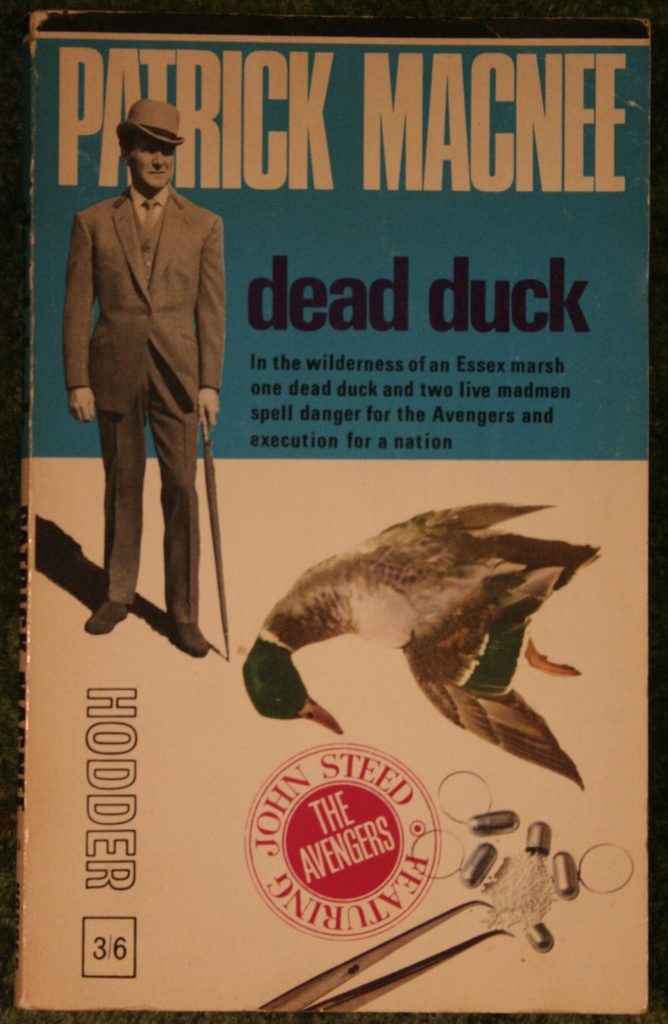

Until now. Here we are in 1967, and Ted White, from his lofty position of power as chairman of NyCon 3, this year’s World SF Convention, has decided that the time has come to expand the existing Best Fanzine Hugo. I think that many of we actifans would welcome additional awards for Best Fan Writer and Best Fan Artist. However, the NyCon 3 committee – and I think we must assume this is mostly Ted – decided to unilaterally create a new class of awards, the Fan Achievement Awards, by analogy to the Science Fiction Achievement Awards, and to nickname them the “Pongs”, by analogy to the “Hugos”.

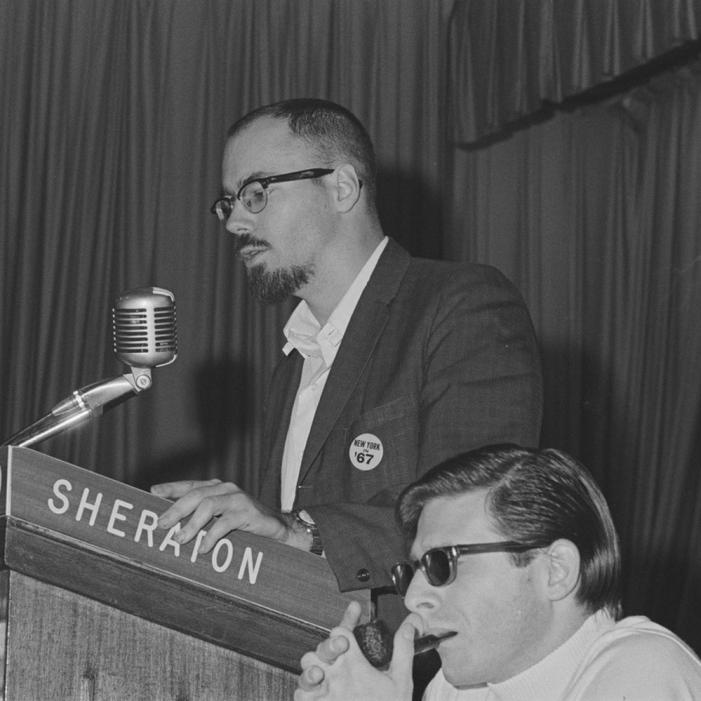

Ted White at last year's Worldcon (Tricon).

It is entirely a matter for the committee of the current World SF Convention to decide which Awards are made. From time to time, fans have suggested that this should be more formalised, but those attempts have never lasted for more than the current year, as each new committee puts their own stamp on the Convention. So this year, as Buck Coulson writes in *Yandro* #169, “[Ted] scorned to use manipulation, propaganda, persuasion or even tact; he just came out, open and aboveboard, with his coup.” But as we see below, Coulson – for whom White is a regular columnist – was not actually averse to the idea.

Back and Forth

Fan editors as a whole, however, have not been pleased, to say the least. Following general grumblings, the *Double:Bill* editors, Bill Bowers and Bill Mallardi, wrote to five influential faneds. Three wrote back rapidly to agree with the Bills’ view that these awards should be Hugos; one replied verbally, and only one dissented – Buck Coulson, who as the Bills archly point out, already has a Best Fanzine Hugo.

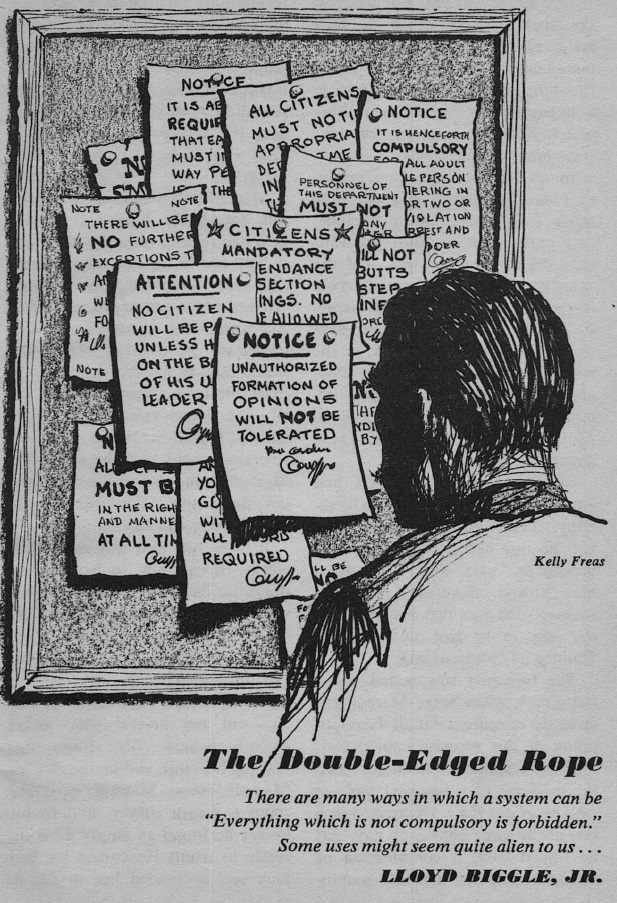

Tom Reamy goes further, and suggests that, “We should outlaw such changes on the whim of the half-dozen who just happen to be the con committee. Any change the committee wants to make should be voted on by the membership and stop all this nonsense.” That might be a step too far; one can easily see how these arrangements could quickly become an unwieldy bureaucracy.

Despite the nomination form listing this as a done deal, and not containing any opportunity for comment, a quarter of the returned ballots argued that the awards should be named Hugos instead, and the idea of the Fan Achievement Awards be forgotten. The Convention committee did not follow that advice. Instead they reported that three-quarters of ballots supported the Pongs – quite the prevarication given that they were merely those that had not actively complained.

Although Tucker is much beloved as the “first fannish fan”, even some of the people who think that the Fan Achievement Awards are a fine idea are not persuaded that the best nickname for them would be the Pongs. Offense concerns aside, Hoy Ping Pong, and Tucker’s many other Pong-related pen names, are only known to dedicated fannish fans. Pong himself seems to exist primarily as Tucker’s alter ego; if the ‘Chinese Buck Rogers’ had adventures, we never learn of them. Many of the fans who have commented on this little furore have found the choice of “Pong” to be baffling.

Wilson Tucker in his younger years

Some of the fans who do support the move do so for the most cynical of reasons. They argue that the Best Fanzine Hugo has already been debased as a result of one or more winners who are to their minds unworthy. Therefore, why not start again with a new set of awards, which, while nominated and voted for by the same imperfect Convention members, will no doubt deliver a far better outcome? I trust most of you will be able to spot the flaw in that argument.

Finally, it may only be here in Britain where the word “pong” means a peculiar and off-putting smell, but that seems to me to be another excellent reason why we would not want our highest awards for fan activity to be called after one. The ‘Hugos’ are traditionally a stylish and weighty rocket ship, redolent of, well, the future. Let our imaginations not trouble us too much with thoughts of what a ‘Pong’ award might look like.

Let Bye-pongs be Bye-pongs

Regardless of our feelings about the Pongs, it is time for everyone who is a World SF Convention Member to vote for the Hugos, including for what I hope will be the Best Fanzine, Best Fan Artist and Best Fan Writer Hugos. Although there is not space for it on the form, I suggest that you take the opportunity to make your feelings clear when you mail in your vote.

This is not just an academic exercise! Our own dear Galactic Journey is a nominee for Best Fanzine for the fourth time [at least, so we were told–I can’t find us on the ‘67 Hugo ballot…(ed)]. Would we be content to win a Pong, rather than a Hugo? Nobody does fanzines intending to win awards, but if we were to win, the Traveler and company would need to decide whether to accept our Pong, or turn it down as many faneds are suggesting.

Will the NyCon3 committee relent, and award Hugos rather than Pongs to the best fanzine, fan writer and fan artist of the year? Watch this space.

Thanks to Fanac for source material, and to Mark Plummer who additionally provided useful material from his own collection.

[Per the latest ‘zines, it does appear the Nycon Committee has relented, and the “pong” will go the way of the dodo. Thank goodness! (ed)]

![[June 22, 1967] The Pong Arising from the World Convention](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/670622hugos-672x372.png)

![[June 20, 1967] Yours sincerely, wasting away (July 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/670620cover-649x372.jpg)

![[June 16, 1967] What's Going On Here? (June 1967 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/670616covers-672x372.jpg)

![[June 10, 1967] Music To Read By (July 1967 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/fantastic_196707-2-1.jpg)

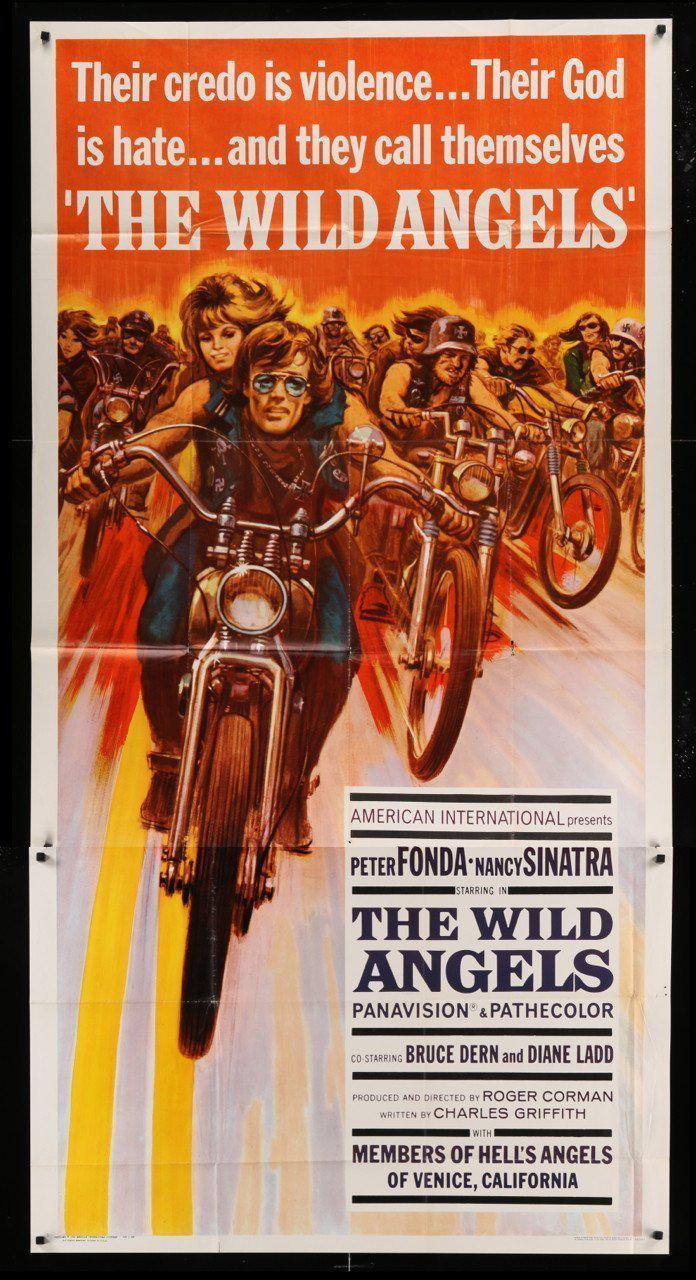

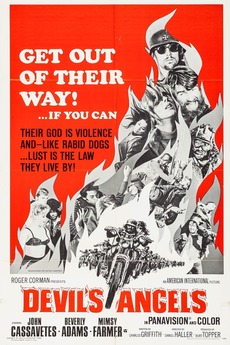

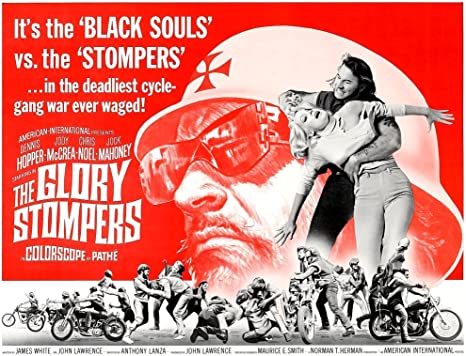

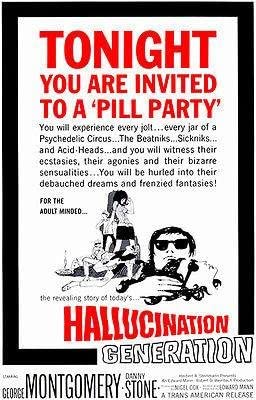

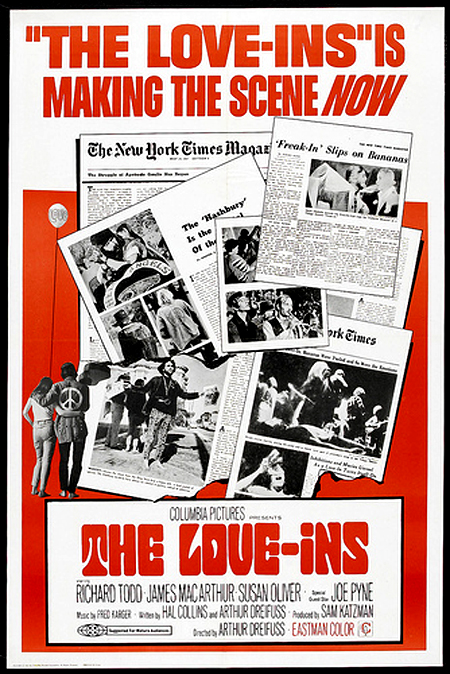

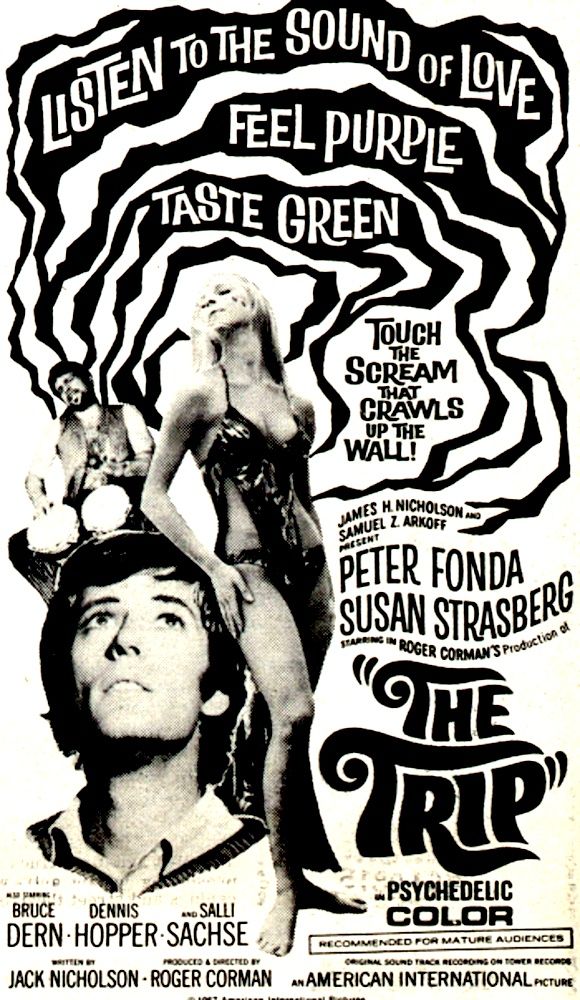

![[June 8, 1967] Rebels With And Without Causes (<i>Riot on Sunset Strip</i> and <i>The Wild Angels</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Untitled-2-672x372.jpg)

![[June 4, 1967] The Daleks Stoop To A New Low… Vehicle Theft! (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Evil Of The Daleks [Part 1])](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/660604dalek-672x372.jpg)

![[June 2, 1967] Uneasy Alliances (July 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/IF-Cover-1967-07-672x372.jpg)

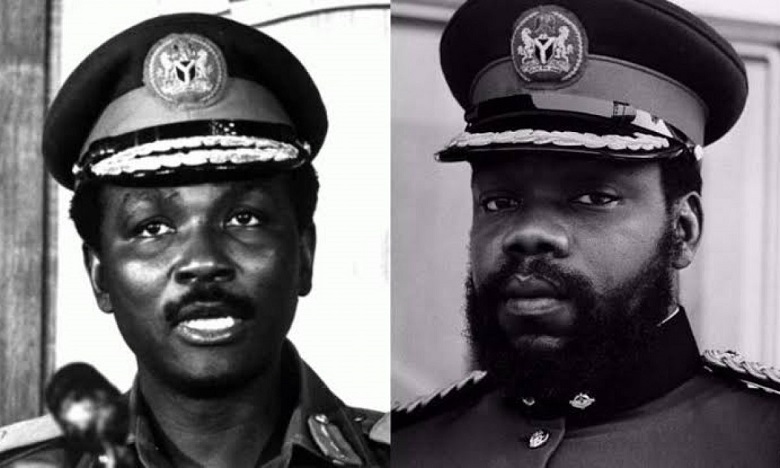

l.: Colonel Yakubu Gowon of Nigeria. r.: Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu of Biafra.

l.: Colonel Yakubu Gowon of Nigeria. r.: Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu of Biafra.  Joe Miller is the most fearsome warrior these vikings have ever seen. Art by Gaughan

Joe Miller is the most fearsome warrior these vikings have ever seen. Art by Gaughan![[May 31, 1967] Phoning it in (June 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/670531cover-672x372.jpg)

![[May 22, 1967] Parable in SF's clothing (The Space Trilogy, by C.S. Lewis)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/670522covers-672x372.jpg)

![[May 20, 1967] Field trips (June 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/670520cover-449x372.jpg)