by Victoria Silverwolf

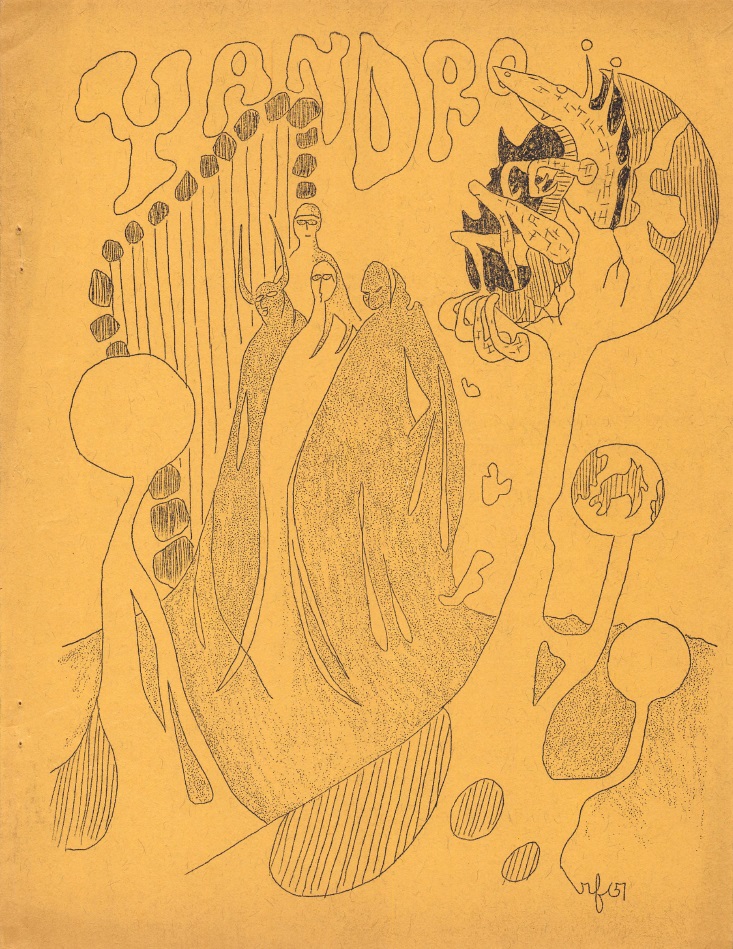

Welcome to the last of our three discussions about an anthology of original fantasy and science fiction that's drawing a lot of attention. Love it or hate it, or maybe a little of both, it's impossible to ignore. I showed you the full wraparound cover the the first time, and offered a closer look at the front the second time, so here's the back cover. It gives you a convenient list of the authors.

As before, I'll give each story the usual star rating as well as using the colors of a traffic light to indicate how dangerous it might be.

Dangerous Visions, edited by Harlan Ellison

Art by Leo and Diane Dillion.

Go, Go, Go, Said the Bird, by Sonya Dorman

A woman desperately tries to escape her pursuers. Flashbacks tell us more about this dystopian world.

Saying anything more would lessen the impact of this intense little story. Ellison's introduction compares it to the work of Shirley Jackson, and that's a fair analogy. It's deceptively quiet and matter-of-fact at times, but full of icy horror at its heart.

Four stars. YELLOW for unrelieved grimness.

The Happy Breed, by John T. Sladek

In the near future, machines take care of all our problems, leaving us to enjoy a life of leisure. Of course, what the machines think is best for us may not agree with our own ideas.

This dark satire on automation isn't exactly subtle. It makes its point clearly enough, and follows it to its logical conclusion. The details of the characters' degeneration make it worth reading.

Three stars. YELLOW for cynicism.

Encounter with a Hick, by Jonathan Brand

Our smart aleck narrator tells us how he met a fellow from a less sophisticated background and what happened when he told the man something about the origin of his planet.

You'll probably figure out the punchline of this extended joke. Despite its predictability, I enjoyed the story's wise guy style. Others may find the narrator annoyingly smug.

Three stars. YELLOW for a wry look at deeply held beliefs.

From the Government Printing Office, by Kris Neville

Set at a near future time when childrearing has changed in an eye-opening way, this yarn is told through the eyes of a kid who is only three and one-half years old. Adults are bewildering creatures indeed!

The quirky choice of viewpoint, with its combination of precocity and naiveté, is what makes this story worth a look. I'm not quite sure what the author is saying about parents and children, but it's provocative.

Three stars. YELLOW for an unflattering portrait of Mom and Dad.

Land of the Great Horses, by R. A. Lafferty

All over the world, people with Romany ancestors feel compelled to return to a place that vanished long ago. But what will disappear next?

This synopsis fails to capture the author's eccentric style and unusual combination of whimsy and oddball speculation. If you like Lafferty, you'll enjoy it. If not, you won't. Like many of his works, it's something of a tall tale and a shaggy dog story. I dug it.

Four stars. GREEN for kookiness.

The Recognition, by J. G. Ballard

The narrator witnesses a woman and a dwarf set up a strange menagerie at night, not far from where a carnival is in progress. The mystery of the cages deepens as visitors show up.

I find this story difficult to describe. It's quite a bit different from the author's jagged, chopped up pieces for New Worlds, and from his decadent tales of Vermillion Sands. It's very subtle, and there seems to be more than meets the eye. The premise evokes thoughts of Ray Bradbury, but only in an extremely subdued way. Maybe haunting is the word I'm looking for.

Four stars. GREEN for intriguing writing.

Judas, by John Brunner

A robot sets itself up as God. One of the people who created it sets out to destroy the false deity.

The plot is simple enough, and the analogy between the worship of the robot and Christianity is made crystal clear. You may predict the twist ending, given the story's title.

Three stars. YELLOW for religious themes.

Test to Destruction, by Keith Laumer

The leader of a group of rebels is captured by the forces of a dictator. They use a gizmo to retrieve information from his brain. Meanwhile, in what has to be the wildest coincidence of all time, aliens approaching Earth also probe his brain, in order to learn how to conquer humanity. The combination is explosive.

Looking at my synopsis, I get the feeling that this isn't the most plausible story in the world. Since it's by Laumer, you know it's a fast-moving adventure yarn. As a matter of fact, it's so lightning-paced that it makes his other stories look slow. The reader is left breathless. There's a serious point made at the end, but mostly it's just a thrill ride.

Three stars. GREEN for action, action, action.

Carcinoma Angels, by Norman Spinrad

The delightfully named Harrison Wintergreen is a guy who has always gotten what he wanted out of life. As a kid, baseball cards. As a young man, women. As an adult, tons of money. Now he's got terminal cancer. Can he triumph over the ultimate challenge?

As Ellison says in his introduction, this is a funny story about cancer. Sick humor, to be sure. Bad taste? Well, maybe, but I think you'll get a kick out of it.

Four stars. YELLOW for black comedy.

Replace a bullfight with a battle between man and car, and you've got this tongue-in-cheek tale. All the details of a traditional corrida del toros are here, transformed to fit the automotive theme.

It's a one idea story, to be sure, but stylish.

Three stars. GREEN for elegant writing.

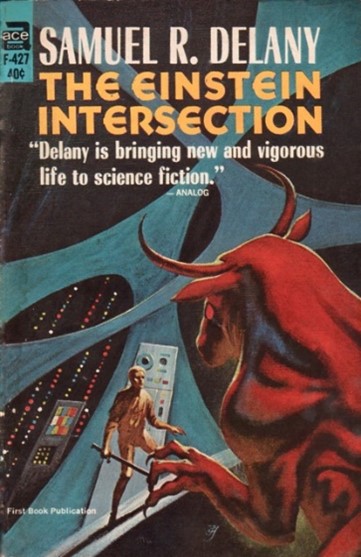

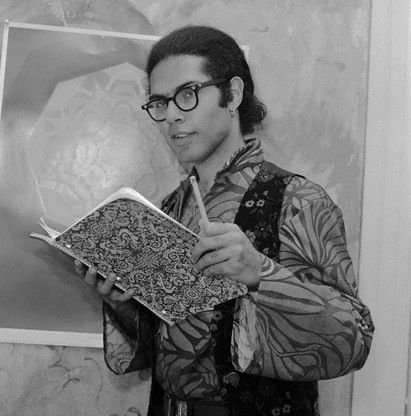

Aye, and Gomorrah . . ., by Samuel R. Delany

Space explorers are raised from childhood to be absolutely free of sexual characteristics. It's impossible to tell if they started off as female or male; they are completely neuter in every way. People known as frelks are attracted to them.

Amazingly, this is the first short story Delany ever sold, although others have already appeared in magazines. It's superbly written, as you'd expect, and explores sex and gender in completely new, profound ways.

Five stars. RED for unimagined forms of human sexuality.

20 20 Hindsight

Looking back at the book as a whole, it's clear that the level of stories is generally high, with a few clunkers. Not all the stories are dangerous, and they could have been published elsewhere. A few are truly groundbreaking. The Silverberg, Leiber, and Delany are the best. The Sturgeon is the biggest disappointment. The Farmer is going to start the most arguments. Put on your reading glasses, fasten your seat belt, and give it a try.

![[January 10, 1968] Saving the Best For Last (<i>Dangerous Visions</i>, Part Three)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/1967_Dangerous-Visions-hc-672x372.jpg)

![[January 8, 1968] Seeing Double…Again (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Enemy Of The World [Part 1])](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/680108seeingdouble-672x372.jpg)

![[January 4, 1968] How much for that fuzzy in the window? (<i>Star Trek</i>: The Trouble with Tribbles")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/680104title-672x372.jpg)

![[January 2, 1968] The consequences of success (February 1968 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/IF-1968-02-Cover-672x372.jpg)

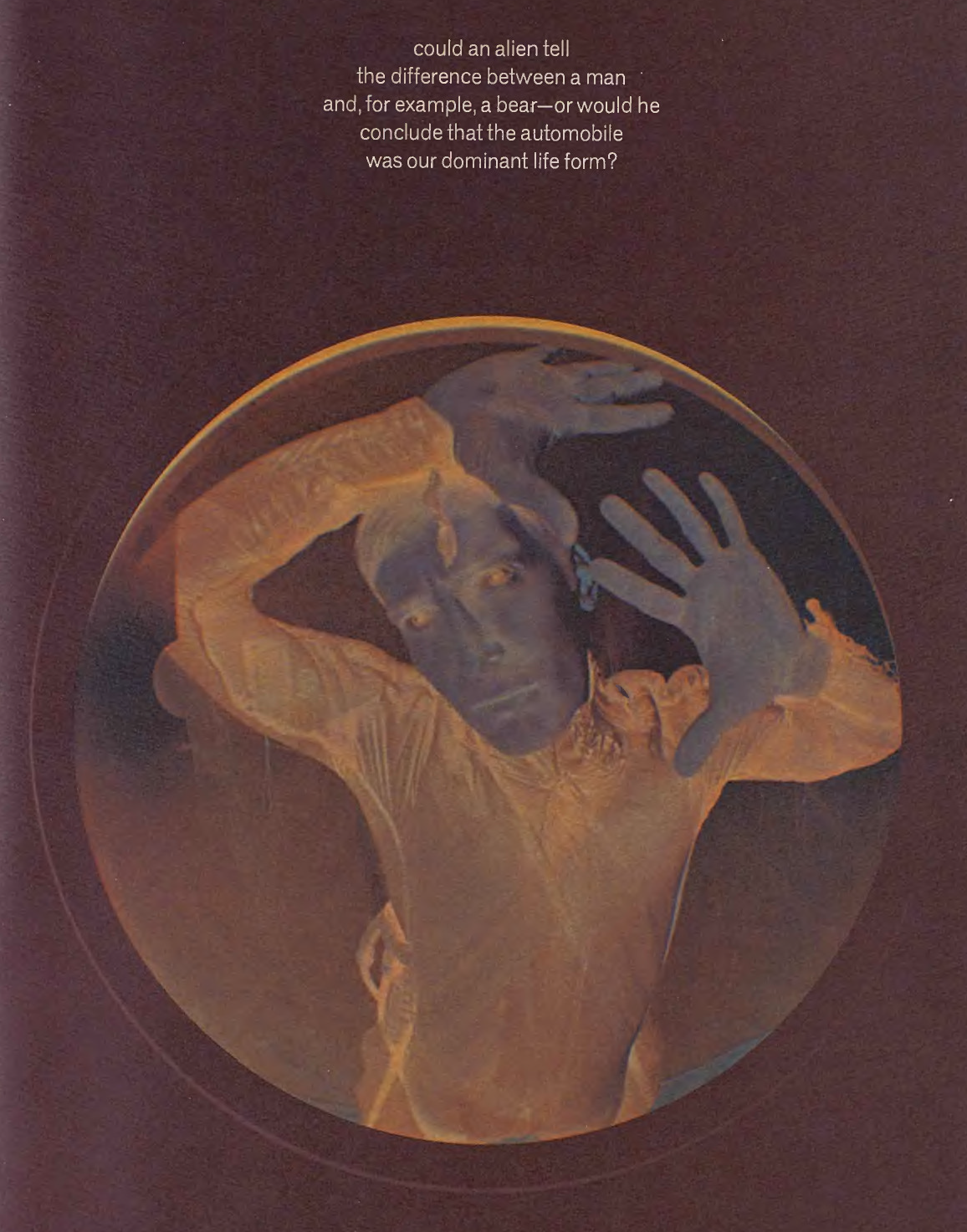

Louis Washkansky talks to Dr. Barnard in the days following the surgery.

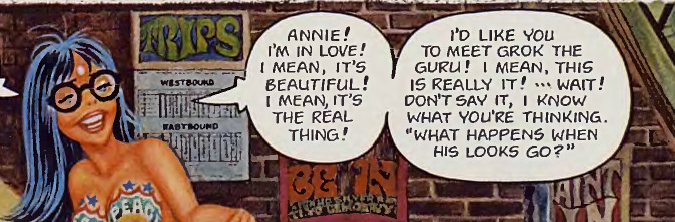

Louis Washkansky talks to Dr. Barnard in the days following the surgery. This dreamscape doesn’t appear in Robert Sheckley’s new story, but it could. Art by Vaughn Bodé

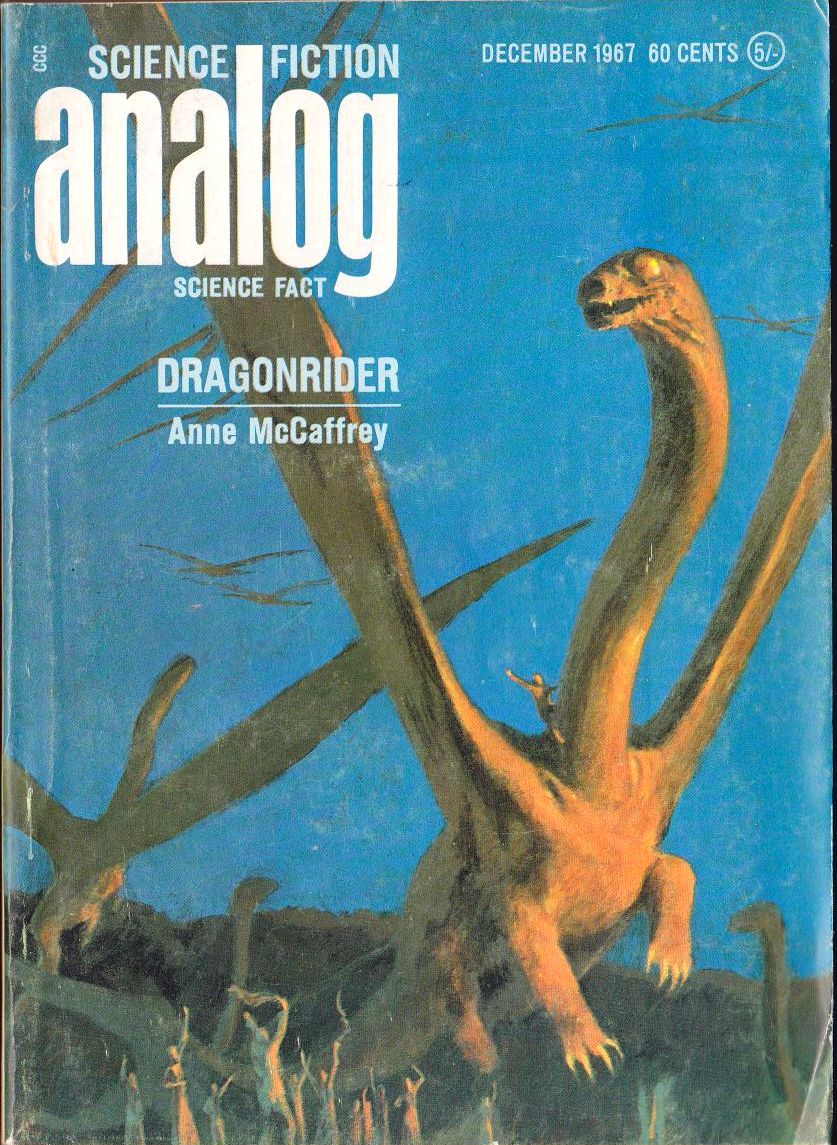

This dreamscape doesn’t appear in Robert Sheckley’s new story, but it could. Art by Vaughn Bodé![[December 31, 1967] Surprise, surprise! (January 1968 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/671231cover-669x372.jpg)

![[December 28, 1967] Stumbling Bloch (<i>Star Trek</i>: "Wolf in the Fold")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/671228title-672x372.jpg)

![[December 24, 1967] Hit Parade '67 (the year's best science fiction)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/671224galaxy-624x372.jpg)

![[December 22, 1967] In all the old familiar places (<i>Star Trek</i>: "Obsession")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/671222title-672x372.jpg)

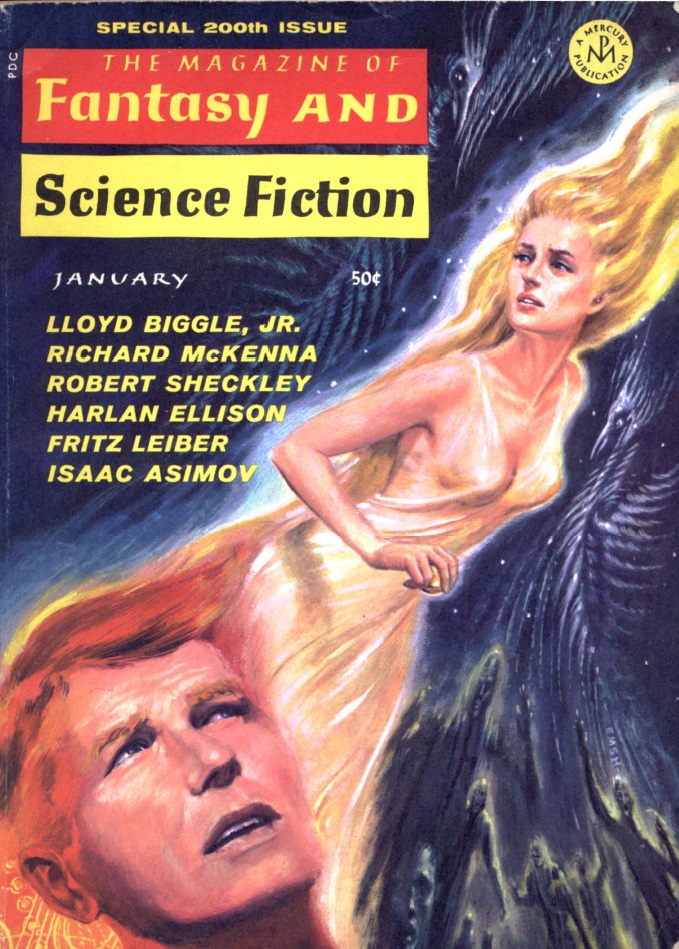

![[December 20, 1967] Smut! (January 1968 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/671220cover-672x372.jpg)