by Victoria Silverwolf

From Arabia to Japan

The collection of Middle Eastern folktales known in English as Arabian Nights or One Thousand and One Nights is familiar to folks all over the world. Case in point, as Rod Serling might say, is the recent Japanese animated film Senya Ichiya Monogatari, which is loosely based on the collection.

Japanese poster for the film. I don't know if it will ever show up elsewhere.

I should point out that this is not a cartoon intended for children. Like the work which inspired it, it contains considerable erotic material. If it ever gets released in the USA, it might get the infamous X rating.

I bring this up because the latest issue of Fantastic contains the first part of a new novel inspired by the same source as the film.

Cover art by Johnny Bruck

As is often the case lately, the cover is (ahem) borrowed from a German publication.

Die Herrscher der Nacht (The Ruler of the Night) is the title of the German translation of Jack Williamson's 1948 novel Darker Than You Think.

Editorial, by Ted White

The editor begins by telling us how the magazine's lead serial (see below) fell into his hands. Long story short, it failed to find a publisher, got reviewed in a fanzine, Ted White read it and liked it. He then goes on to relate the big changes in Fantastic and its sister publication Amazing. My esteemed colleague John Boston has already discussed this in detail, so let me give you the Reader's Digest version. Higher price, more words, only one reprint per issue. Nuff said.

No rating.

Hasan (Part One of Two), by Piers Anthony

Illustrations by Jeff Jones.

More than half the magazine consists of the first installment of this Arabian Nights fantasy adventure.

Hasan is a rather naive and foolish young man, living in Arabia around the year 800 or so. He meets a Persian alchemist who demonstrates how to turn copper into gold. His mother warns him not to trust this fire-worshipping infidel, but Hasan's greed overcomes what little common sense he possesses.

The wicked Persian kidnaps him and takes him on an ocean journey to the island of Serendip. (We call it Ceylon nowadays—the magazine provides a helpful map).

Despite this, Hasan still trusts the alchemist enough to perform the dangerous task of being carried to the top of a mountain by a roc, in order to gather the stuff needed to transform copper into gold. The poor sap doesn't realize that the Persian intends to leave him stranded on the peak, where he'll starve to death.

Suffice to say that, with a lot of dumb luck, Hasan makes his way to an isolated palace inhabited by seven beautiful sisters, who adopt him as their brother. He goes on to witness birds change into even more beautiful women, one of whom he is determined to have for his bride. (She has little say in the matter.)

Seeing her naked while she is bathing makes him fall madly in love.

Without giving away too much, let's just say that the further adventures of Hasan and the bird woman will appear in the next issue.

The author appears to be well acquainted with One Thousand and One Nights, given his accompanying article on the subject (see below.) As far as I can tell, he captures the flavor of this kind of Arabian folktale in a convincing way. Despite the fact that the hero is kind of a dope, and that the female characters (except Hasan's long-suffering mother) mostly exist to be alluringly beautiful, this half of the novel makes for light, entertaining reading.

Three stars.

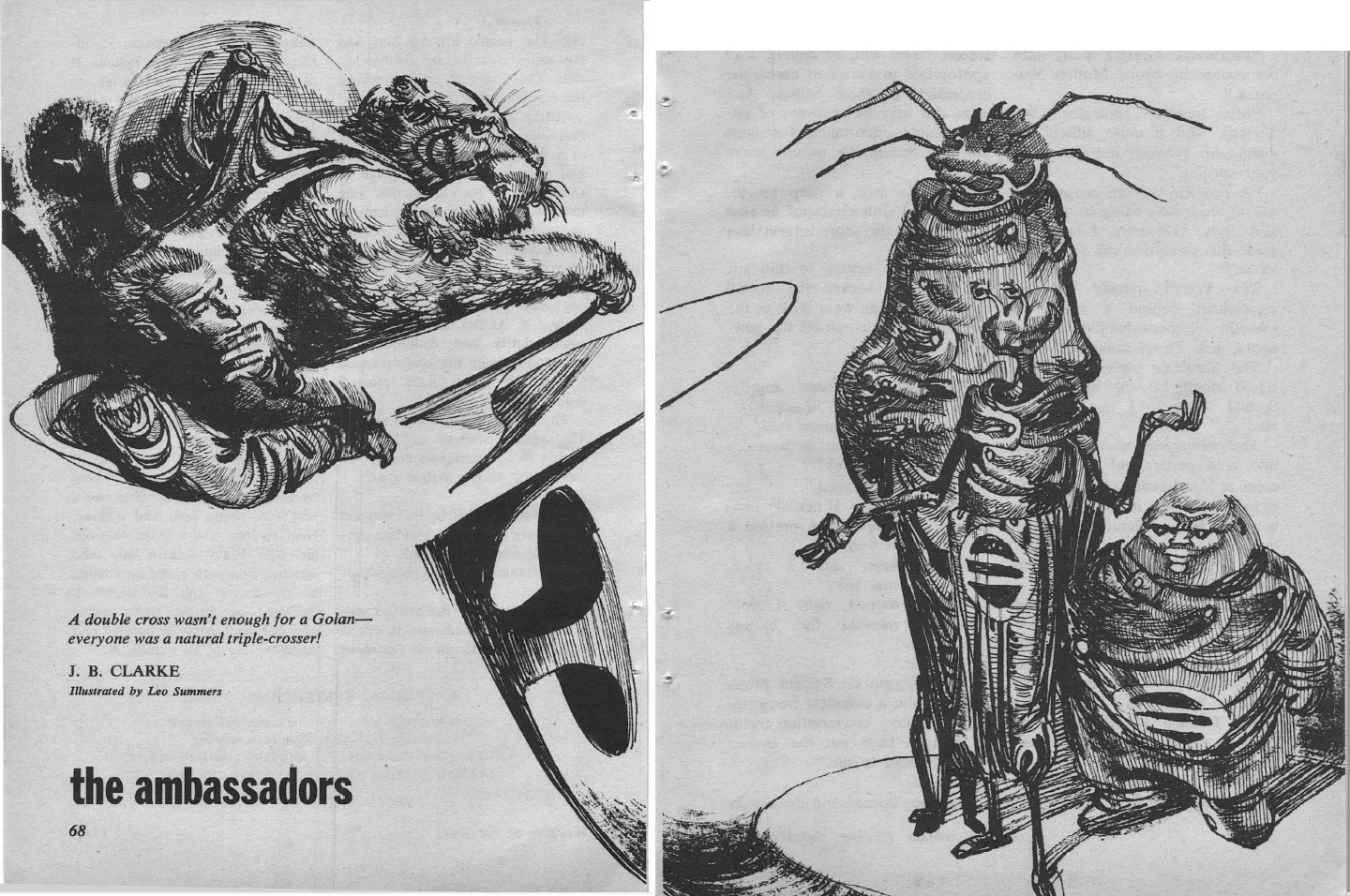

Morality, by Thomas N. Scortia

Illustration by Bruce Jones.

It's obvious from the start that this is a science fiction version of the myth of the Minotaur, although the author doesn't make this explicit until the end. The legendary monster is an alien stranded on Earth, forced to serve an ambitious king while trying to contact his own kind.

There's not much more to this story than its retelling of the old tale. It plays out just as you'd expect.

Two stars.

Would You? by James H. Schmitz

A wealthy fellow invites an equally rich acquaintance to make use of a magic chair. It seems that it has the ability to allow the person seated in it to change the past.

I hope I'm not revealing too much to state that neither man chooses to alter his past, preferring to leave well enough alone. That seems to be the point of the story. A tale of fantasy in which an enchanted object is not used is unusual, I suppose, if not fully satisfying.

Two stars.

Magic Show, by Alan E. Nourse

A couple of guys watch a magic show at a cheap carnival. One of them heckles the magician, who invites him to take part in his greatest feat.

You can probably see where this is going. No surprises in the plot. I have to wonder why a real, powerful magician works at a lousy little carnival.

Two stars.

X: Yes, by Thomas M. Disch

An unspecified referendum always appears on the ballot in every election. Everybody knows that the proper thing to do is vote No. A woman chooses to vote Yes, just as children vote Yes during their mock elections.

Can you tell that this is an odd little story? I'm not sure what the author is getting at, unless it's something about conformity and rebellion. At least it's not a simple, predictable plot. Food for thought, I guess.

Three stars.

Big Man, by Ross Rocklynne

The April 1941 issue of Amazing Stories supplies this wild yarn.

Cover art by J. Allen St. John.

I can't argue with the accuracy of the title. A gigantic man — he's said to be one or two miles tall — walks through the Atlantic Ocean to Washington, D. C. The behemoth is under the control of a Mad Scientist, who intends to take over the United States government and run things the way he thinks they should be run.

Illustration by Robert Fuqua.

It's up to a heroic pilot and his girlfriend (who, in an incredible coincidence, turns out to be the sister of the young fellow who was transformed into the giant) to defeat the Mad Scientist and end the reign of terror of the Big Man.

Boy, this is a goofy story. I think the author saw King Kong too many times. The premise is, of course, absurd, and it's treated in the corniest pulp fiction manner imaginable.

One star.

Alf Laylah Wa Laylah — A Essay on The Arabian Nights, by Piers Anthony

As part of the magazine's Fantasy Fandom column, this article is reprinted from the fanzine Niekas. It discusses One Thousand and One Nights in detail, comparing English translations and offering examples of the kinds of tales it contains. Copious footnotes, some serious and some playful. The author clearly knows his subject.

Three stars.

Fantasy Books by Fritz Leiber and Fred Lerner

Leiber quickly gives a positive review of Captive Universe by Harry Harrison, praises Walker and Company for reprinting science fiction classics in handsome hardcover editions, defends the use of strong language in Bug Jack Barron by Norman Spinrad, gives thumbs up to A Fine and Private Place by Peter S. Beagle, and talks about Eric R. Eddison's fantasy novels. He ends this rapid-fire essay by comparing the way that Heinlein, Spinrad, and Eddison describe a woman's breasts. (The latter excerpt is a really wild bit of outrageously purple prose.)

Lerner, in an article reprinted from the fanzine Akos, talks about two nonfiction books about J. R. R. Tolkien. He dismisses Understanding Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings by William Ready as poorly written and overly interpretive, and praises Tolkien: A Look Behind The Lord of the Rings by Lin Carter for its discussion of epic fantasy in general.

No rating.

… According to You, by various

The letters from readers offer both praise and criticism. One of the editor's replies reveals that sales of the magazine went down when Cele Goldsmith was in charge, even though the quality of fiction improved. I hope that's not a bad omen for the way Ted White is taking the publication.

No rating.

Worthy of Scheherazade?

Not a great issue, although Anthony's novel and related essay are well worth reading. The new stuff is so-so and the reprint is laughably poor. It might be better to watch an old movie instead.

![[November 8, 1969] Arabesques (December 1969 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/COVERARTSMALL.jpg)

![[November 6, 1969] I Can See For Miles (Piers Anthony's <i>Macroscope</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/691106macroscopecover-359x372.jpg)

![[November 4, 1969] A Dazzler (Bedazzled, 1967)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/691104bedazzledposter-672x372.jpg)

Stan, about to strike out with Margaret again

Stan, about to strike out with Margaret again The Top of the Pops parody is spot on.

The Top of the Pops parody is spot on. Sermon on the postbox

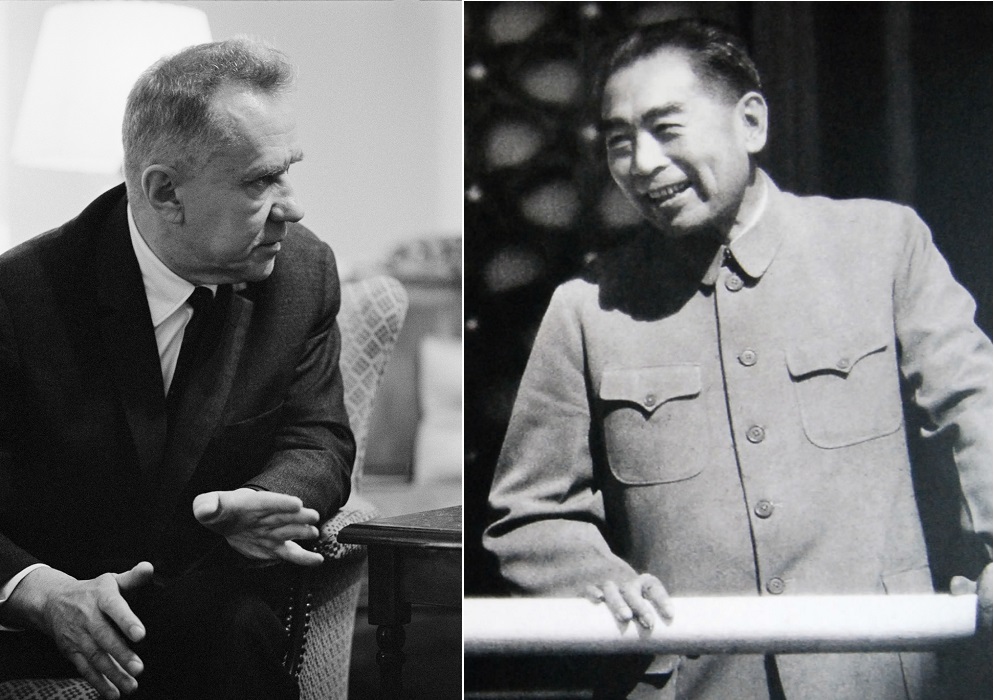

Sermon on the postbox![[November 2, 1969] Love and Hate (December 1969 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/IF-1969-12-Cover-505x372.jpg)

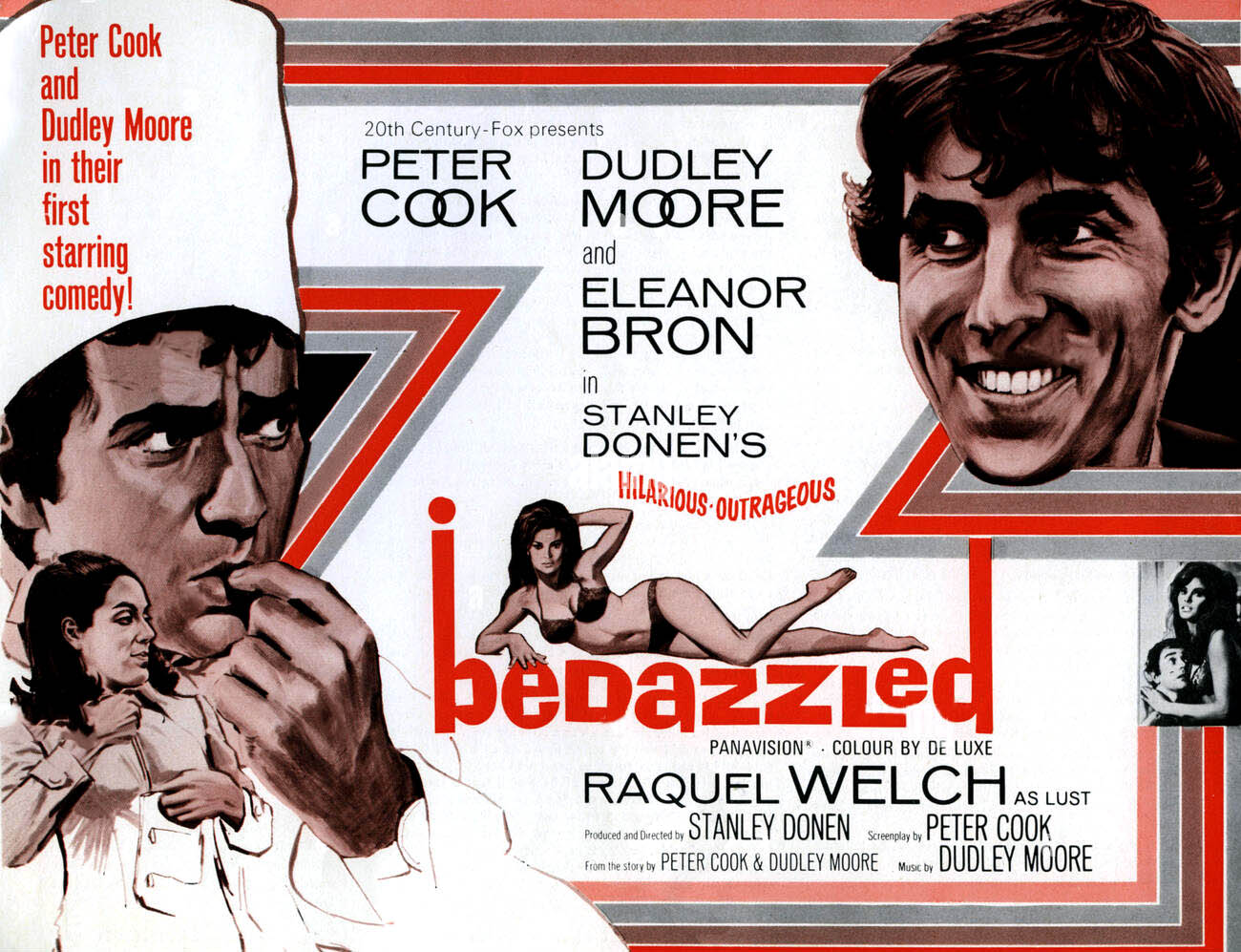

l. Soviet Foreign Minister Alexei Kosygin, r. Chinese Foreign Minister Chou Enlai

l. Soviet Foreign Minister Alexei Kosygin, r. Chinese Foreign Minister Chou Enlai Vaguely suggested by Ancient, My Enemy. Art by Gaughan

Vaguely suggested by Ancient, My Enemy. Art by Gaughan![[Oct. 31, 1969] Struggling to get out (November 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/691031analogcover-672x372.jpg)

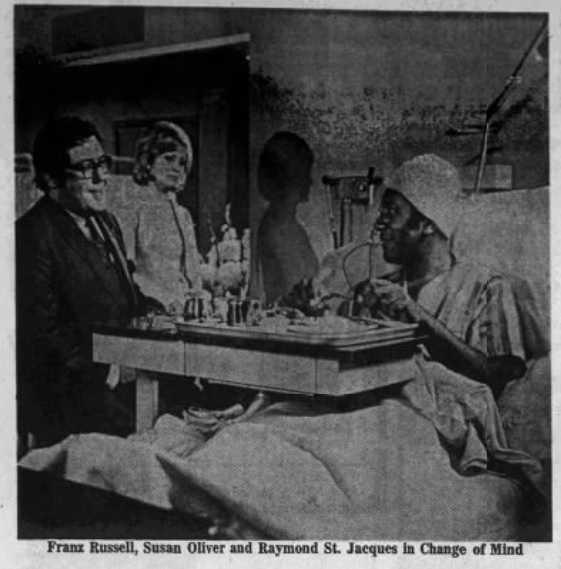

![[October 28, 1969] Black and White (the movie <i>Change of Mind</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/691028end-504x372.jpg)

Cover of November 1969 issue, by John Bayley

Cover of November 1969 issue, by John Bayley Art by Roy Cornwall and definition of Snottygobble

Art by Roy Cornwall and definition of Snottygobble Art by J Myrdahl

Art by J Myrdahl Art and words by Jannick Storm

Art and words by Jannick Storm Art by R Glyn Jones; wow.

Art by R Glyn Jones; wow. The first page of "Alien Territory" by John T. Sladek

The first page of "Alien Territory" by John T. Sladek art by Peter Southern

art by Peter Southern Art by R Glyn Jones

Art by R Glyn Jones An example of pop art; well, something is popping anyway.

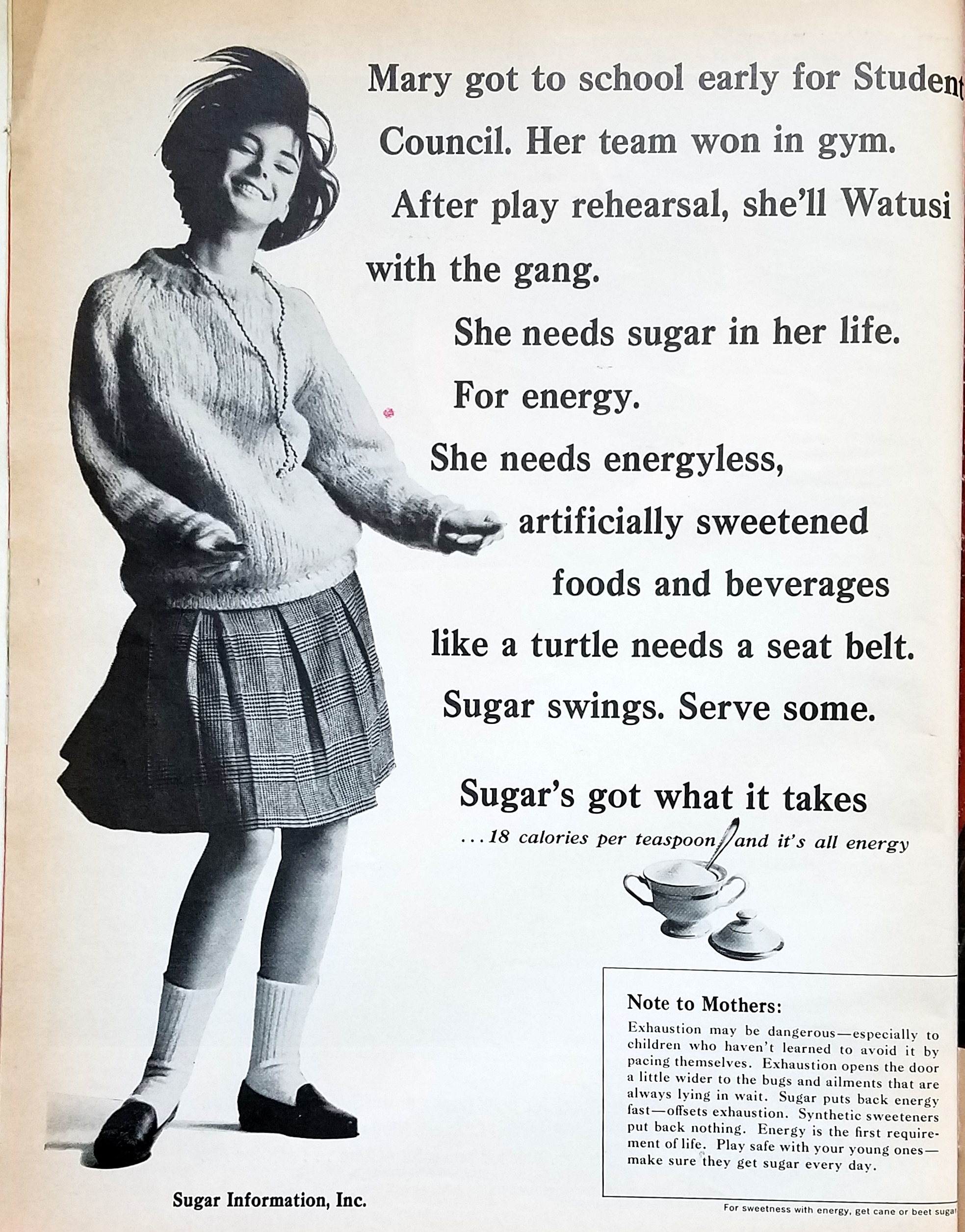

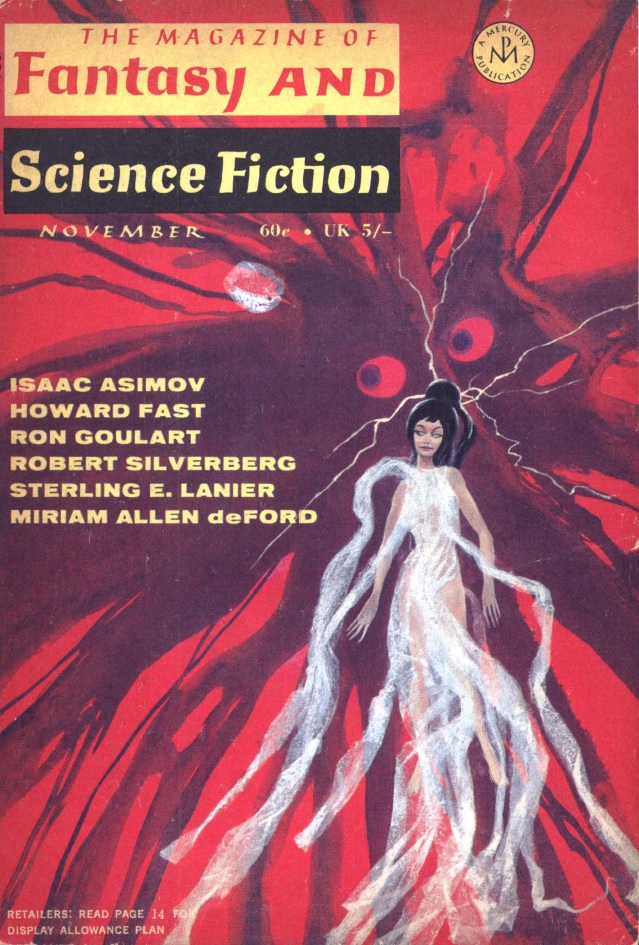

An example of pop art; well, something is popping anyway.![[October 24, 1969] How sweet it isn't (November 1969 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/691024fsfcover-639x372.jpg)

![[October 20, 1969] There was a ship (November 1969 <i>Venture</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Venture-1969-11-Cover-480x372.jpg)

The SS Manhattan breaking through the ice of the Northwest Passage.

The SS Manhattan breaking through the ice of the Northwest Passage. Art by Tanner

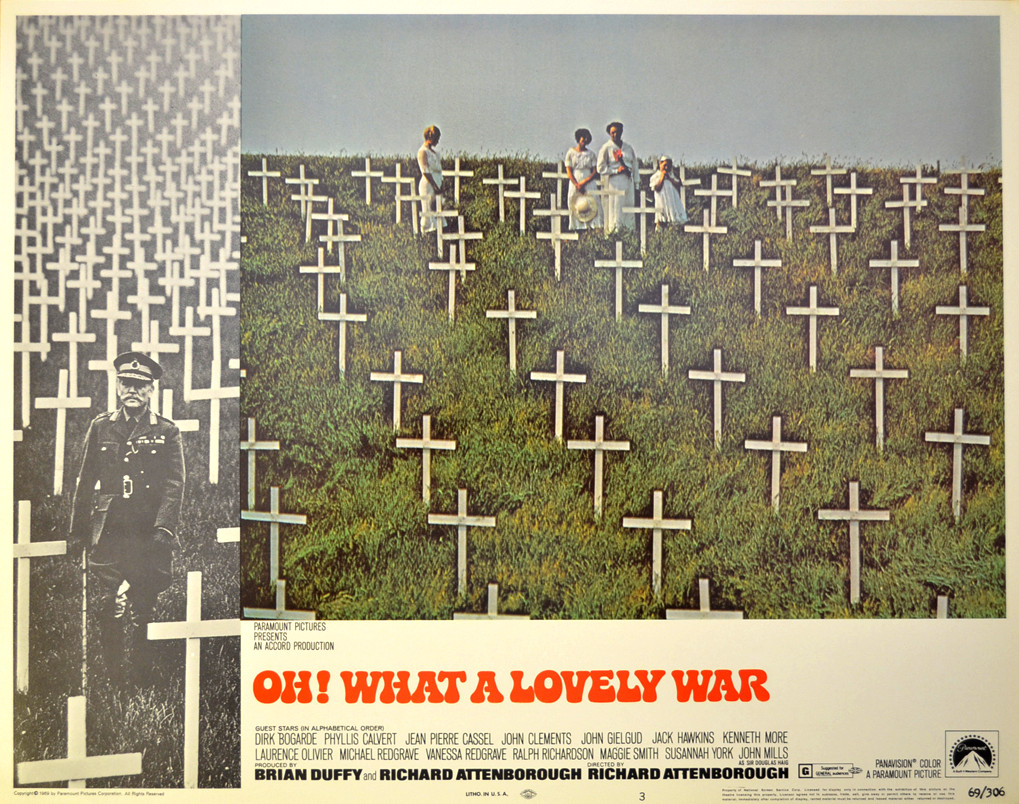

Art by Tanner![[October 18, 1969] Cinemascope: We'd Be Tickled to Death to Go (Moon Zero Two and Oh! What a Lovely War!)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/691018posters-1-672x372.jpg)

Future fashions: must they *always* involve coloured wigs?

Future fashions: must they *always* involve coloured wigs?

The French cavalry charging on merry-go-round horses

The French cavalry charging on merry-go-round horses Maggie Smith sets a honeytrap for unwary recruits

Maggie Smith sets a honeytrap for unwary recruits