So many books this month, and this time, we've got all superlatives. Check out the second June Galactoscope!

Continue reading [June 17, 1970] Time and Again (June Galactoscope Part Two!)

So many books this month, and this time, we've got all superlatives. Check out the second June Galactoscope!

Continue reading [June 17, 1970] Time and Again (June Galactoscope Part Two!)

This month saw such a bumper crop of books (and a bumper crop of Journey reviewers!) that we've split it in two. This first one covers two of the more exciting books to come out in some time, as well as the usual acceptables and mediocrities. As Ted Sturgeon says: 90% of everything is crap. But even if the books aren't all worth your time, the reviews always are! Dive in, dear readers…

As luck would have it, the first three novels to be reviewed this month were all by women! They all have something else in common—they each have both merits and demerits that sort of cancel out…neither Brown, Russ, nor Norton quite hit it out of the park this time at bat.

by Victoria Silverwolf

In Memoriam

An unavoidable note of sadness fills this review of a newly published novel. The author died of lymphoma in 1967, at the very young age of 41. With that in mind, let's try to take an objective look at her final novel.

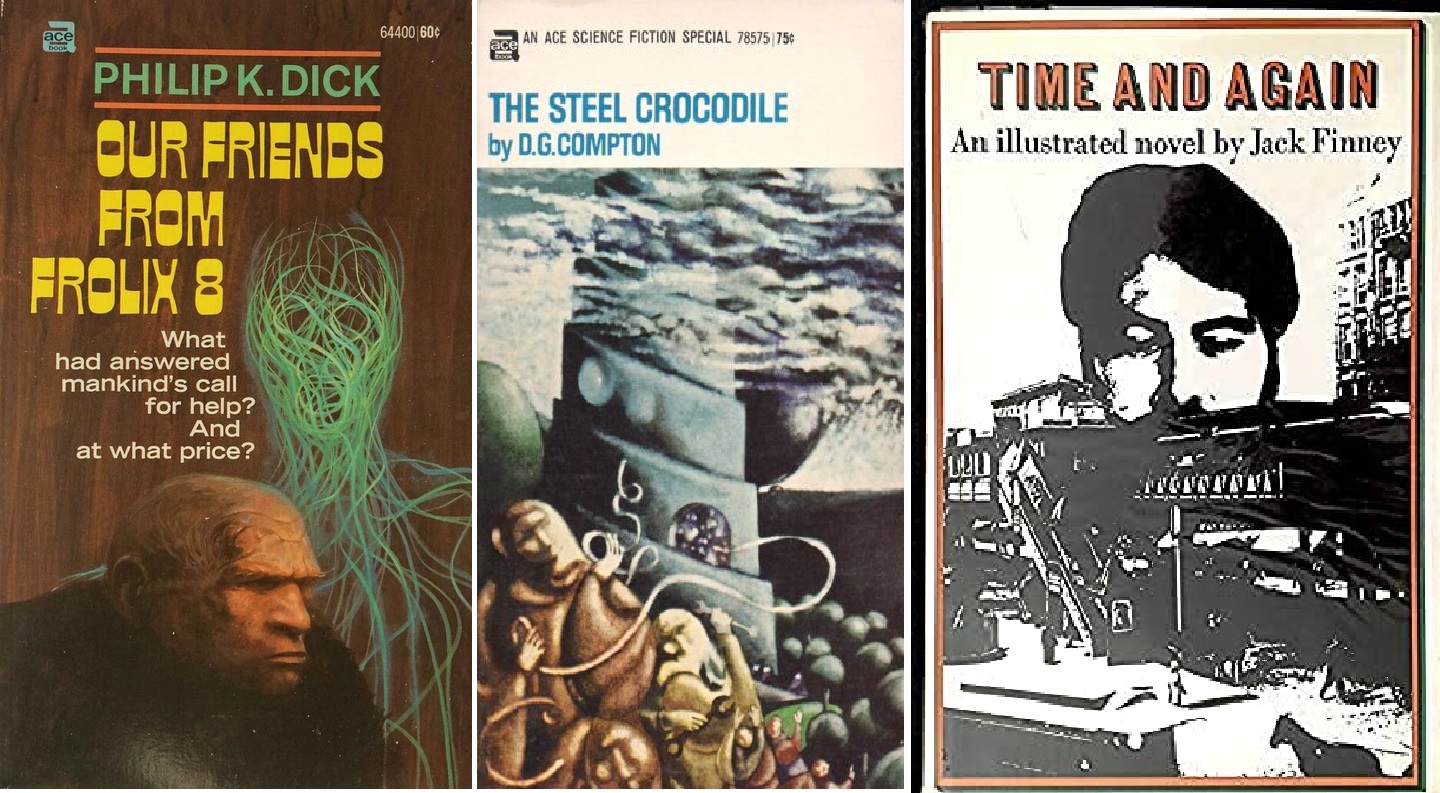

The Waters of Centaurus, by Rosel George Brown

Cover art by Margo Herr

This is a direct sequel to Sibyl Sue Blue. My esteemed colleague Janice L. Newman gave that novel a glowing review. In fact, our own Journey Press saw fit to reprint it in a handsome new format.

Sibyl Sue Blue is back. She's a forty-year-old police detective and a widow with a teenage daughter. She's fond of cigars, gin, fancy clothes, and attractive men.

Continue reading [March 6, 1970] The Waters of Centaurus, And Chaos Died, and High Sorcery

We have a fine sextet of science fiction books for you this month: largely readable, with two clunkers and one superior read…

by Gideon Marcus

Ace Double 66160

Earthrim, by Nick Kamin

Continue reading [December 16, 1969] Holiday haul (Black Corridor and the December Galactoscope)

[And now, for your reading pleasure, a clutch of books representing the science fiction and fantasy books that have crossed our desk for review this month!]

by Victoria Silverwolf

Ye Gods!

Two new fantasy novels, both with touches of science fiction, feature theological themes. One deals with deities that are now considered to be purely mythological, the other relates to one of the world's major living religions. Let's take a look.

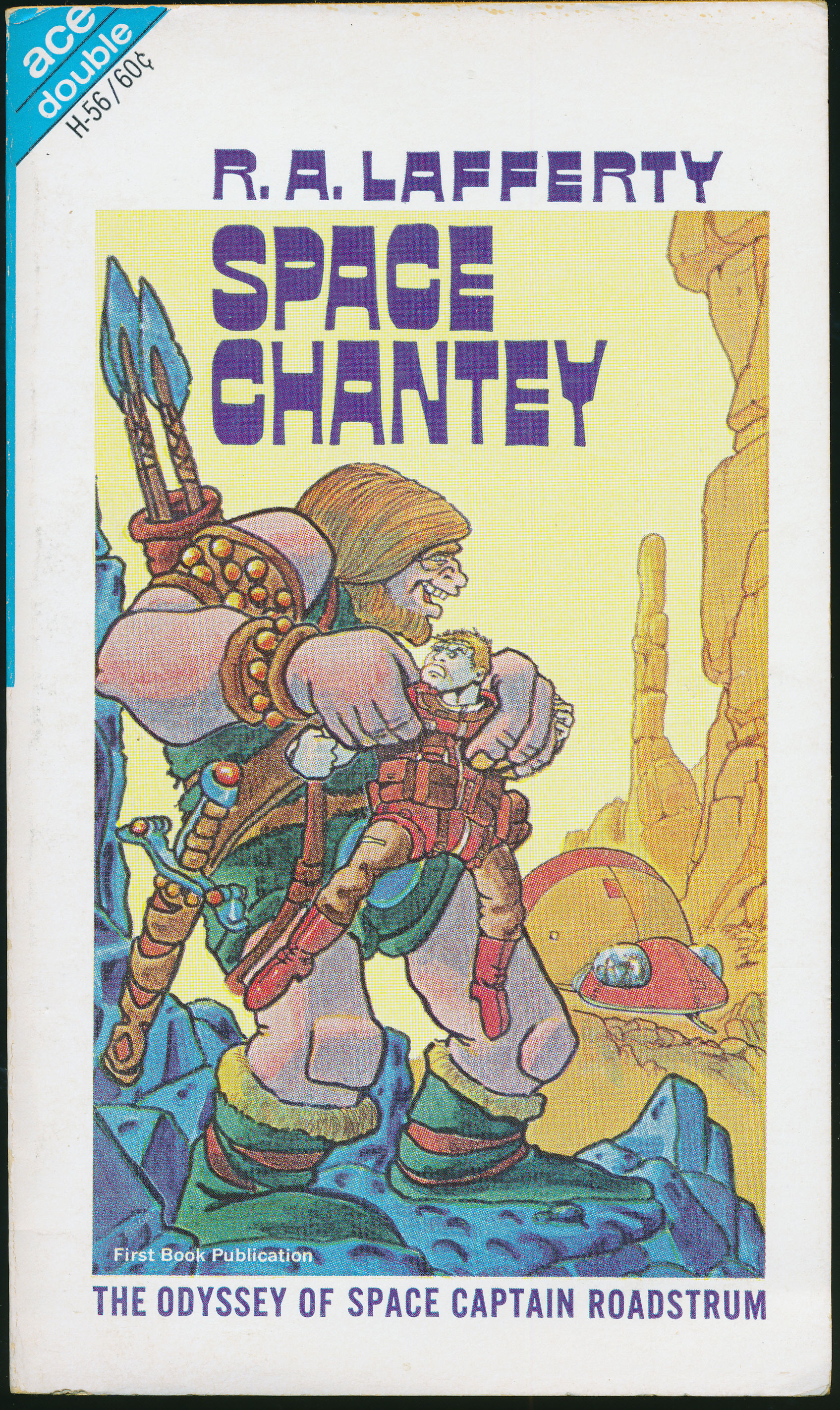

Fourth Mansions, by R. A. Lafferty

Cover art by Leo and Diane Dillon.

The title of this strange novel comes from a book written by Saint Teresa of Avila, a Spanish Christian mystic of the sixteenth century. This work, known as The Interior Castle or The Mansions in English, compares various stages in the soul's spiritual progress to mansions within a castle. From what I can tell from a little research, the Fourth Mansion is the stage at which the natural and the supernatural intersect.

(I'm sure I'm explaining this badly. Interested readers can seek out a copy of Saint Teresa's book for themselves.)

I understand that Lafferty is a devout Catholic, so this connection between his latest novel and what is considered to be a classic of Christian literature must be more than superficial. Be that as it may, let's see if we can make any sense out of a very weird book.

Our hero is Fred Foley, a reporter who is said to be not very bright, but who seems to have some kind of special insight or perception as to events beyond the mundane. (A sort of Holy Fool, perhaps.) He gets involved in multiple conspiracies of folks, who may be something other than just ordinary human beings, out to change the world.

There are four such groups, said to be not quite fit for either Heaven or Earth. Each one is symbolized by an animal.

The Snakes, also known as the Harvesters, are a group of seven people who blend their psychic powers to influence the minds of others. They are intent on bringing about a sort of hedonistic apocalypse. Their connection to Foley and other characters allows for telepathic communication, and sets the plot in motion.

The Toads are folks who are reincarnated, or somehow take over new bodies. (It's a little vague.) Foley's investigation into one such person starts the novel. They intend to release a plague, wiping out most of humanity and ruling over the survivors.

The Badgers are people who are something like spiritual rulers of a kind of parallel world that most ordinary people can't perceive. Foley pays a visit to a couple of these seemingly benign people for information. In one case, this involves a trip to a mountain in Texas that shouldn't be there.

The Unfledged Falcons are would-be fascists, military leaders trying to take over the world by force. Only one such person appears in the book, a Mexican fellow named Miguel Fuentes. He gets involved when the Snakes try to influence an American named Michael Fountain (see the connection in names?) and wind up entering his mind by mistake.

I would be hard pressed to try to describe all the bizarre things that happen. Lafferty has a way of describing extraordinary events in deadpan fashion. (We're very casually told, for example, that one character brought a dead man back to life when he was a boy. One very minor character is a demon, and another one is an alien.)

The book's combination of whimsey and allegory is unique, to say the least. There's a lot of dialogue that sounds like nothing anybody would ever say in real life. Did I understand it all? Certainly not. Did I enjoy the ride? Yep.

Four stars.

Creatures of Light and Darkness, by Roger Zelazny

Cover art by James Starrett.

Zelazny's recent novel Lord of Light offered a futuristic twist on Buddhism and Hinduism. This one makes use of ancient Egyptian gods, as well as a bit of Greek mythology. There are also a lot of original concepts, making for a very mixed stew indeed.

The time is the far future, when humanity has settled multiple planets. Don't expect a space opera, however.

We begin in the House of the Dead, ruled by Anubis. He has a servant who has lost his memory and his name. Anubis gives him the name Wakim, and sends him to the Middle Worlds (the physical realm) to destroy the Prince Who Was A Thousand. Meanwhile, Osiris, who rules the House of Life, sends his son Horus on the same errand.

You see, Anubis and Osiris keep the population of the Middle Worlds in balance, bringing life and death in equal amounts. The Prince threatens this system with the possibility of immortality. Although the two gods have the same goal, they are also rivals, so their champions battle each other as well as the Prince.

This is a greatly oversimplified description of the basic plot. A lot more goes on, with many equally god-like characters. There's a sort of scavenger hunt for three sacred items, with the protagonists hopping around from planet to planet in search of them.

Zelazny experiments with narrative techniques, from poetry to a play. There's some humor, as demonstrated by a cult that worships a pair of shoes. (They actually play an important role in the plot.) The pace is frenzied, with plenty of purple prose.

Full understanding of what the heck is really going on doesn't happen until late in the book, when we learn the actual identities of Wakim and the Prince. Suffice to say that this requires a lengthy description of apocalyptic events that took place long before the story begins.

Some readers are going to find this novel disjointed and overwritten. Others are likely to be swept away by the richness of the author's imagination. I'm leaning in the latter direction.

Four stars.

by Fiona Moore

Roger Zelazny’s been busy this month! His new novel Damnation Alley expands his novella of the same name into an action piece which is exciting enough but ultimately unsatisfying, a sort of postapocalyptic pony express with futuristic vehicles and implausible characters.

Cover of Damnation Alley by Jack Gaughan

The story is set in a relatively near-future USA after a nuclear war which has split it into isolated states within a radiation-ravaged wasteland, the only relatively safe passage through which is a corridor known as Damnation Alley. There are pockets of radiation, giant mutant animals and insects, tornadoes and killer dust storms. The descriptions of these is the book’s real strength, with some of them verging on the genuinely poetic. Our protagonist is Hell Tanner, a former Hell’s Angel who is offered a pardon for his crimes by the State of California, if he’ll deliver a shipment of vaccines to Boston, which has been hit by an outbreak of plague. Of course, this necessitates driving through Damnation Alley, but never fear, Tanner is also driving a super-tough vehicle bristling with weaponry.

The whole thing is almost laughably macho in places, and I say that as someone who really quite likes both cars and adventure stories. Tanner is that implausible archetype, the bad guy who nonetheless somehow has other people’s best interests at heart. However, there’s also some nice contrasts set up between Tanner and the criminal world he inhabits and the much more normal parts of society he encounters on his journey, where people seem to be on the whole generally decent and kind, making Tanner’s casual violence seem all the more out of place.

The book has a lot of problems. Some are clearly the result of padding it out to novel length, with several episodes which go nowhere and add little to the story. The characterisation of everyone aside from Tanner is weak to nonexistent. In particular, the main female character, Cordy, is a frustrating cipher: she is a woman who Tanner essentially abducts, and yet she shows none of the emotions one might expect under the circumstances, while Tanner seemingly comes to think of her as his girlfriend despite neither of them making any moves in that direction.

However, the biggest problem is that there are too many holes in the story for it to stay afloat. Despite the devastation of the land around it, the state of California somehow still has the resources to build giant armoured cars bristling with every kind of weapon from bullets to flamethrowers. Only two human beings are apparently capable of making the trip from California to Boston, which is surprising given the aforementioned level of technology and that there is clearly no shortage of young men with a death wish. Tanner makes it almost to Boston before encountering anyone who makes a serious effort to steal the vaccines, which I also find somewhat implausible. And so on, and so on.

Damnation Alley held my attention for the duration of a train journey and had nicely surreal, well-paced prose in places, but it was just too unbelievable for me to really enjoy it. Two and a half stars.

Since he returned to writing some half a dozen years ago, Robert Silverberg has tried to reintroduce himself as a more “serious” writer. This is not to say his rate of output has slowed down in favor of more refined work; if anything the past few years have been the busiest for him since the ‘50s. This year alone we have gotten enough novels from Silverberg that a bit of a catch-up is in order. The first on my plate, Across a Billion Years, hit store shelves a few months ago, from The Dial Press (I believe this is Silverberg’s first book with said publisher), and it seems to have flown under the radar—possibly because there’s no paperback edition, and also it might be aimed at younger readers. The second book we have here, To Live Again, is from Doubleday, and it too is a hardcover original; but unlike Across a Billion Years, To Live Again is a new release, fresh out of the oven.

Across a Billion Years, by Robert Silverberg

It’s the 24th century, and humanity has not only spread to other worlds but encountered several intelligent alien races along the way. Tom Rice is a 22-year-old archaeologist on an expedition to find the ruins of a bygone race called the High Ones, who apparently lived a billion years ago (hence the title) but who have since vanished. Whether or not the High Ones have gone extinct is one of the novel’s core mysteries, although Silverberg takes his time raising this question. The novel is told as a series of diary entries, or rather messages Tom sends to his sister Lorie. In a curious but also frustrating move, Lorie is arguably the most interesting character in the novel, yet we never see or hear her, as she’s not only away from the action but stuck in a hospital bed for an indefinite period. Lorie is a telepath, and enough people are “TP” to make up their own faction, although telepathy only works one-way and Tom himself is not a telepath. The one positive surprise Silverberg includes here is finding a way to tie telepathy together with the mystery of the High Ones, but obviously I won’t say how he does it.

As for bad surprises, well…

Even taking into account that Tom is a young adult who also has personal hang-ups (his father wanted him to enter real estate), his treatment of his colleagues is abhorrent in the opening stretch. He dismisses the aliens on the team as mostly “diversity” hires and has a standoffish relationship with Kelly, the female android on the team, whom he more than once compares to a “voluptuous nineteen-year-old.” Why someone of Tom’s age would make such a comparison is befuddling…unless you were really a lecherous man approaching middle age and not a recent college graduate. There are a few other humans here, but the only human woman present is Jan, whom Tom gradually takes a liking to—just not enough to do anything when he sees Leroy, a male colleague, sexually assault Jan near enough that he could have intervened. This happens early in the novel, and I have to admit that Tom’s indifference regarding Jan’s wellbeing, a weakness in character he never really apologizes for, cast a cloud over my enjoyment of the rest of the novel. I kept wondering when the other shoe would drop. That Tom and Jan’s relationship turns romantic despite the former’s callousness only serves to rub salt in the wound. The bright side of all this is that while some of Silverberg’s recent work has bordered on pornographic, Across a Billion Years is relatively tame, almost to the point of being old-fashioned.

Indeed, this feels like a throwback to an older era of SF, even back to those years when Silverberg (and I, for that matter) had not yet picked up a pen or used a typewriter. In broad strokes this is a planetary adventure of the sort that would have been serialized in Astounding circa 1945. We’re excavating alien ruins on Higby V, a distant planet where High Ones artifacts have been supposedly found. During a drunken escapade one of the alien diggers stumbles upon (or rather breaks into) a piece of High Ones technology, something akin to a movie projector, not only showing what the High Ones look like but revealing a clue as to the location of their homeworld. This should sound familiar to most of us, and I suspect Silverberg knows this too, because this novel’s biggest problem and biggest asset is how it uses perspective. We’re stuck with Tom as he sends messages to Lorie, recounting events in perhaps more detail than he has to, knowing in advance that his sister won’t receive these messages until after the fact. As with a disconcerting number of Silverberg protagonists, Tom can be annoying, and honestly quite bigoted; and since he is the perspective character we’re never relieved of his oh-so-interesting remarks. But, and I will give Silverberg this, he does put a twist on the epistolary format very late in the novel, which does the miraculous thing of making you reevaluate what you had been reading up to this point.

In other words, this is not an exceptional novel, but it does have its points of interest, and with the exception of an early scene and its ramifications (or lack thereof), nothing here made me want to throw my copy at a nearby wall. For the most part this is inoffensive—possibly even decent. Three stars.

To Live Again, by Robert Silverberg

Those who want a bit more sex with their science fiction can do worse than this one, which looks to be the fourth (or maybe fifth—I’ve lost count) Silverberg novel of 1969. It’s the near-ish future, and the good news is that for those with enough money, death is not necessarily the end. Courtesy of the Scheffing Institute, a person can have their memories stored periodically, making copies or “personae” of themselves, which can be transplanted to the brain of a living host. The host and the persona will cooperate, lest the latter erase the former’s personality and become a “dybbuk,” using the host’s body as a flesh puppet.

The infamous businessman Paul Kaufmann has recently died, with his persona waiting to be claimed. Paul’s nephew, Mark, and Mark’s 16-year-old daughter Risa each see themselves as ideal candidates for Paul’s persona, but one of the rules at the Institute is that close family members can’t host each other’s personae: the implications of, for example, a teen girl hosting her grandfather’s persona, would be…concerning.

While we’re on the lovely topic of incest, let’s talk more about Risa, who must be one of the thorniest of all Silverberg characters, which as you know is a tall order, not helped by the fact that Silverberg describes, in almost poetic detail, every curve of this teen girl’s nude body—and she does strut around naked a surprising amount of the time. Risa is such a depraved individual, despite her age, that she at one point tries seducing an older male cousin and rather openly has an Electra complex (they even mention it by name), which Mark is understandably disturbed by—with the implication being that Mark has lustful thoughts about his own daughter. This is the second Silverberg novel I’ve read in two months to involve incest, which worries me.

The only other major female character is Elena, Mark’s mistress, whom Risa sees as a rival for her father’s affections and who (predictably) starts conspiring against Mark. Not content to ogle at just 16-year-olds, Silverberg also takes to describing the nuances of Elena’s body in wearying fashion, which does lead me to wonder if he was working the typewriter one-handed for certain passages. It’s a shame, because there’s an intriguing subplot in which Risa acquires her first persona, a young woman named Tandy who had died in a skiing accident—or so the official record claims. Tandy, or rather the persona of Tandy, recorded a couple months prior to her death, suspects foul play. Of the women mentioned, Tandy is the least embarrassingly written, but then she is only tangentially related to the plot and, what with not having a physical body, Silverberg is only able to ogle at her so much.

I’ve not even mentioned John Roditis and his underling Charles Noyles, business rivals of Mark’s who are clamoring for Paul’s persona. You may notice that this novel has more moving parts than Across a Billion Years, and certainly it’s the more ambitious of the two, the problem being that its shortcomings are all the more disappointing for it. Silverberg raises questions that he can barely be bothered with answering, and he alludes to things that remain mostly unrevealed. Much of To Live Again is shrouded in speculation, which is to say it uses speculation as a night-black cloak to cover things we sadly never get to see.

Another rule at the Institute is that a persona has to be of the same gender as its host, a rule that characters mostly write off as bogus. And indeed why not? Why should a male host and female persona not be able to coexist? Or the other way around. The prohibition has to do with transsexualism, which is certainly uncharted water for the most part. There has been very little science fiction written about transsexualism or transvestism—the possibility of blurring and even crossing gender lines. Unfortunately the novel does little with the ideas it presents. There are multiple references to religion and mythology (the word “dybbuk” refers to an evil spirit in Jewish mythology), including lines taken from the Tibetan Book of the Dead. There’s a minor subplot about white Californians appropriating Buddhist practices, in connection with the Institute, but this is so tangential that the reader can easily forget about it.

Finally, I want to mention that I was reminded eerily of another novel that came out this year, Philip K. Dick’s masterful and deranged Ubik, which I have to think Silverberg could not have known about when he was writing To Live Again. Both take cues from the Buddhist conception of reincarnation, although in Dick’s novel people who have died are kept in a state of suspended animation called “half-life,” whereas Silverberg’s characters die the full death, or “discorporate,” only that their personalities (up to a point) are kept intact. Not to make comparisons, but given that Silverberg’s novel is longer than Dick’s I have to say he does a fair bit less with the shared material. Of course, these are both talented writers, who at their best do very fine work indeed. Silverberg has become a major writer, but sadly he is not firing on all cylinders with either of the novels I’ve covered.

Hovering between two and three stars on this one.

by George Pritchard

The Glass Cage by Kenneth W. Hassler

The mockery for this book writes itself:

And yet, I can't hate it the way I hated Light A Last Candle. That book was one mass of forgettable hate, but The Glass Cage is not hateful. It's incompetent at every turn, from line editing to plot development (I really don't know how it got the hardcover copy I received), but the overall effect is an oral record of a children's game.

There's this guy, Stephen, he’s twenty! He's a neophyte to the priests of the computer, TAL! It keeps life going in the city beneath its glass dome! Stephen is a perfect physical specimen, and his only flaw is being too curious about things. But that's because he’s secretly a spy for the Rebellion outside the glass dome!

The sentences are short and rarely have the benefit of internal punctuation. The characters are, generally, exactly how they appear — wicked characters with their close-together eyes, good characters with their strong jaws, straightforward manner, and perfect blonde hair. If this is chosen for adaptation, Tommy Kirk is made for the lead part.

The treatment of nuclear power seems to come from another time, where the leaders of interstellar development are in the Baltimore Gun Club rather than NASA. The giant computer, TAL, is attached to a nuclear bomb, to go off at a certain date, destroying the whole glass dome and the people within! No need to worry, though, Stephen and his various Rebellion people get most everyone out in time, except for the bad guy head priest of TAL, who is determined to die with his machine. Stephen and the gangster leader of the in-Dome Rebellion try to get him out, but to no avail! The nuclear bomb is about to go off, so the two of them hop on their air-sled, turn it skyward, and smash through the glass dome, just as the nuclear bomb goes off! Luckily, the nuclear bomb just pushes them a few miles away from the blast, where they are safe and unharmed.

One point of the book that is surprisingly forward-thinking is its treatment of one of the main characters being severely disabled. Despite being paralyzed from the neck down, he is a leader of the Rebellion, commanding through his immense psychic ability. But that cannot keep me from giving it…

Two stars

[A bit of a downer note to leave on, but at least there's some fine stuff upstream. See you next month, tiger!]

It's a highly superior clutch of books this month around—plus a double review of the new Vonnegut…

by Victoria Silverwolf

Sophomore Efforts

By coincidence, the last two books I read were both the second novels to be published by their authors. Otherwise, they are as different as they could be.

The Null-Frequency Impulser, by James Nelson Coleman

Cover art by John Schoenherr.

Coleman's first book was something called Seeker From the Stars. I haven't read it, so I can't comment. In fact, I was completely unfamiliar with this author, so I asked my contacts in fandom and the publishing industry about him. I turned up a couple of interesting facts.

Firstly, he's one of the few Black science fiction writers. (The most notable is, of course, the great Samuel R. Delany.) That's a good thing for the field. The more variety of writers, the better the fiction.

Secondly, he's currently in jail for burglary. It seems that he's taken up writing while incarcerated. That seems like a decent path to rehabilitation, so let's wish him good luck while paying his debt to society.

But is the book any good? Let's find out.

At some time in the future, humanity has reached the far reaches of the solar system. However, a conglomeration of business interests known as the Five Companies has put a stop to further development of space science, unless they control it. They're so powerful that they have their own secret police. Not even the World Government or the Space Patrol can keep them from crippling research.

Our protagonist is Catherine Rogers. She is part of a private space research group that dares to defy the Five Companies. Trouble starts when a scientist shows up at their headquarters, shot by the secret police. Just before dying, he gives Catherine and her colleagues a book and a key to a hidden cache of highly advanced technology brought from another world.

We quickly find out that two aliens in the form of glowing spheres are on Earth. One of them is insanely evil. He kidnapped the other, who is essentially the queen bee of her species. He intends to mate with her against her will, forcing her to produce one hundred million offspring (!) who will be raised to be as wicked as himself.

He wants to feed off the life force of human beings, and teach his children to do the same, wiping out humanity. Complicating matters is the fact that the evil alien shares his mind with one of the leaders of the secret police, who wants to get his hands on the advanced technology.

This all happens very early in the book, and we've got a long way to go. Suffice to say that Catherine and her friends work with the good alien, who has enormous psychic powers, to defeat the bad one.

The author's writing style isn't very sophisticated, sad to say, nor is the plot. Much of the time I imagined this story as a comic book. On the good side, the pace keeps getting faster and faster. By the end, it makes Keith Laumer look like Henry James.

I also appreciate the fact that the heroes are of mixed races, and a large number of them are women. All in all, however, I have to confess that this is a disappointing work.

Two stars.

The Place of Sapphires, by Florence Engel Randall.

Uncredited cover art.

Randall's first novel was called Hedgerow. I haven't read that one either, but apparently it's a Gothic Romance without supernatural elements.

Unlike Coleman, I'm familiar with this author. She had two excellent stories published in Fantastic a few years ago.

Will she be as adept at a longer length? Let's take a look.

An automobile accident claims the lives of the parents of two sisters. Elizabeth (twenty-four years old) escapes without a scratch, but Gabrielle (nineteen) is severely injured. The two young women move into a house owned by the great-aunt of a doctor who cared for Gabrielle during her long and painful recovery.

The house is located on an island off the coast of New England, the perfect setting for a Gothic Romance. Elizabeth and the doctor fall in love, giving us the other mandatory element for this genre.

The first half of the book is narrated by Gabrielle. On the very first page she feels the presence of Alarice, a woman who lived in the house long ago. (She's the dead sister of the great-aunt. Throughout the book, there's a strong parallel between the two pairs of sisters, including a love triangle.)

It's obvious from the start that Gabrielle is mentally and emotionally unstable, after her traumatic experience, so it's not always clear what's real and what's not. The second half of the book is narrated by Elizabeth, who gives us a very different perspective on events, including the tragic accident.

I haven't mentioned a third narrator, who shows up only a few pages from the end, adding a genuinely chilling touch.

This is a beautifully written book, with great psychological insight into its characters. Besides gorgeous language that makes me want to read it out loud, it has a plot as intricately woven as a spider web. We witness the same things happen from different viewpoints, completely changing what we thought we knew.

Five stars.

by Brian Collins

This month's Ace Double is a very good one for both Fritz Leiber fans and readers in general. The quality packed into this Double is unsurprising, though, since it is all reprints. There's the short collection Night Monsters, which contains four stories that all run in the horror vein. Three of these stories were previously printed in Fantastic, and so Victoria covered them some years ago. The other half is The Green Millennium, one of Leiber's more overlooked novels, first published in 1953 and not having seen print in the U.S. in about fifteen years.

Ace Double 30300

Cover art by Jack Gaughan and John Schoenherr.

The Black Gondolier, by Fritz Leiber

The longest story here is also the best, at least in terms of the sheer beauty of Leiber's prose. It's Southern California in the early '60s, and the narrator is recounting the strange ramblings of a friend of his who would disappear under mysterious circumstances. Said friend believes that not only is oil a corrupting force, but that oil might somehow be alive. The supernatural is never seen but is strongly alluded to, in passages so evocative, so oppressive, that they compare with Conrad's Heart of Darkness. The plot itself is rather structureless, but this doesn't matter because Leiber is so good at chronicling modern horrors such as industry and the urban landscape. I lived in California (in Pasadena) for a short time, and I'll be sure never to return.

Five stars.

Midnight in the Mirror World, by Fritz Leiber

Another contender for best in the collection is a more personal, more melancholy story. A middle-aged man, a chess-player, astronomer, and divorcee who reads somewhat like a stand-in for Leiber, sees a silhouetted figure behind him in the doubled mirrors he sees going up and down the stairs every night. Without giving away the ending, the apparition may be the ghost of a theatre actress he had met by chance who had committed suicide not long after their encounter. The man, in an attack of conscience, is confronted with a memory he had suppressed, of a person he had deeply wronged, though he didn't know it at the time. It's a ghost story, a striking portrait of guilt, and in a strange way, a love story.

Five stars.

I'm Looking for "Jeff", by Fritz Leiber

As an unintended companion to the previous story, this one is interesting. It also features a ghostly woman who has been wronged, albeit the crime committed upon her is much worse. We're led to believe at first that this woman is simply a temptress, but while she may creep up on the unsuspecting male lead, she is not a totally malicious specter. "I'm Looking for 'Jeff'" is about a decade older than the other stories, and it certainly shows a restraint (given the horrific crime at the center) that Leiber would probably not show if he had written it today. My one real problem is the ending, which is an expositional monologue from a third party that explains the twist, rather than Leiber showing us what happened.

Four stars.

The Casket-Demon, by Fritz Leiber

The last and shortest is also the most lighthearted; it's what you might call a horror-comedy. An actress is quite literally fading (her body is becoming more transparent) as her popularity is on the decline, so she resorts to a very old family ritual that might make her famous again—at a price. The satire is cute, although I think Leiber tackled something similar but better and more seriously in "The Girl with the Hungry Eyes." I'm also not sure about those rhyming couplets. It's fine, but ultimately minor.

Three stars.

The Green Millennium, by Fritz Leiber

Phil Gish is aimless and unemployed, but his life quickly gets turned upside down when he meets a green cat he takes an immediate liking to. He calls the cat Lucky, and like Lovecraft, who liked taking care of strays, he thinks of the animal as his own—only for Lucky to run off. Man gets cat, man loses cat, man goes looking for cat. This is the skeleton on which the book's plot is built, but it balloons into something much weirder and more convoluted.

The future America of The Green Millennium is dystopic, but not in ways we now take as obvious. Robots have become normalized, taking away much of human labor, and the people themselves are largely hedonists desperate for stimulation—not even for pleasure itself but more to fight off boredom. Despite being first published in 1953, it reads like something written in the past few years—in the wake of the New Wave and even something like Pynchon's The Crying of Lot 49. Certainly it could not have been serialized in the magazines of the time, what with the explicit references to sex and drug use.

The plot, at its core, is simple, but Leiber introduces a colorful array of characters, all of whom want Lucky as much as Phil does. These characters include, but are not limited to, a husband-wife wrestling duo, an analyst who sounds like he himself could use an analyst, a woman with prosthetic legs that hide what seem to be hooves for feet, a pack of corporate higher-ups who may as well be mobsters, actual mobsters, and a few others I have not mentioned. The green cat might be an alien, or a mutant, or a weapon devised by the Soviets, I won't say which.

I might sound inebriated as I'm trying to explain all this, but let me assure you that I haven't smoked or ingested marijuana in five months!

Leiber is a mixed bag when it comes to comedy: he can be pretty funny, but he can also write The Wanderer. The Green Millennium is a madcap SF comedy that was written at a time (the early '50s) when Leiber could seemingly do no wrong, and it demonstrates his keen understanding of things that haunt the modern American. Most importantly, it's just a lot of fun.

Four stars.

by Gideon Marcus

Seahorse in the Sky, by Edmund Cooper

On a routine flight from Stockholm to London, sixteen travellers (eight women and eight men) with no connection to each other, find themselves whisked to another world. Their new environs are suggestive of nothing so much as a zoo habitat designed to be reminiscent of home. To wit: a strip of highway flanked by a supermarket and a hotel, complete with electricity and running water. Two automobiles sans engines. A few workshops. A nightly replenished supply of booze, groceries, and tools.

Russell Graheme, M.P., quickly takes charge of the unwilling emigrants, organizing exploration parties. Soon, contact is made with a medievalist enclave, a Stone Age encampment…and what appear to be flocks of fairies.

What is this world? Who brought them there? And to what end? Those are the key riddles answered in this terrific little new book.

It's sort of a cross between Cooper's book Transit (in which five humans are transported to an extraterrestrial island) and Philip José Farmer's "Riverworld" series (in which everyone who ever lived is transported, along with his/her culture, to the banks of an extraterrestrial world-river) with a touch of the whimsy of L. Sprague de Camp (viz. The Incomplete Enchanter). It reads extremely quickly, and what with the short chapters and quick running time, you'll be done with the novel (novella?) before you know it.

What really engaged me, beyond the tight writing and fine characterization, was the central message of hope throughout the book. In "Riverworld", the various cultures who find themselves alongside each other in the hereafter almost immediately form belligerent statelets; war is the constant in Farmer's series. But in Seahorse, it's all about making peaceful contact, working together, having a productive goal. There's no Lord of the Flies to this story (though it is not unmitigatedly happy, either). Cooper clearly has a positive view of humanity, or at least wants to inspire us toward his idealistic vision. Count me in.

Five stars.

Contrast this upbeat book with the other one I read recently…

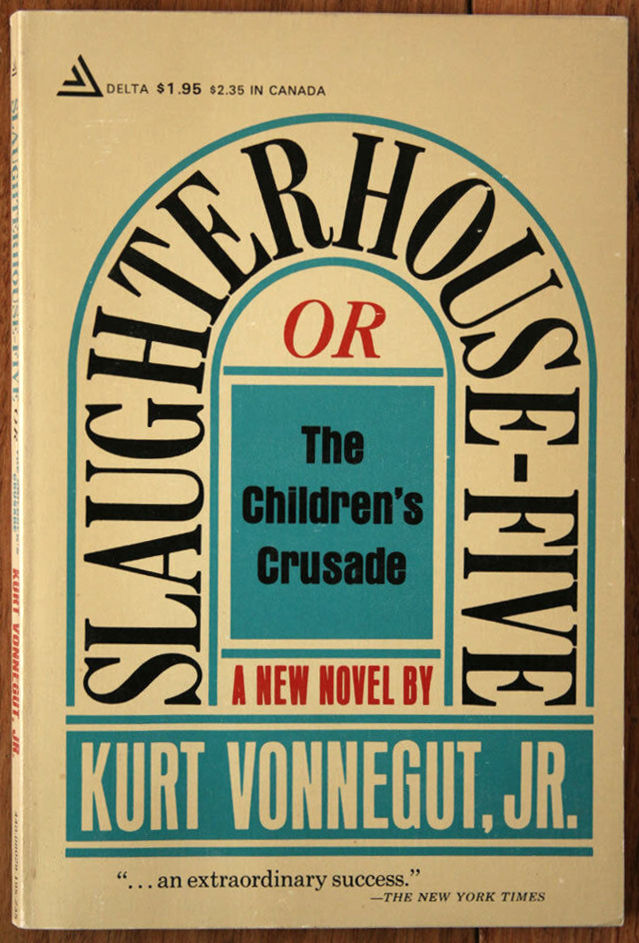

Slaughterhouse Five, by Kurt Vonnegut Jr.

By page 100, Gideon determined that Slaughterhouse Five is not a book one enjoys, but rather experiences.

Two thirds of the way through the book, Gideon realized he'd been hoodwinked. Slaughterhouse Five is not science fiction at all, but rather the author's attempt to convey his experiences as a POW in Nazi Germany during the War, culminating in his presence at the firebombing of Dresden (now sited in East Germany). The SFnal wrapping, in which Billy Pilgrim is abducted by 4D aliens who unstick him in time and incarcerate him in an extraterrestrial zoo, seems there mostly to get eyes on the book. Or maybe to maintain a certain detachment from the material by changing the genre from "memoir."

For the same reason Billy Pilgrim, the eternal schlemiel, gets to be the closest thing the book has to a hero rather than the author, himself. The only way Vonnegut could work through his battle fatigue and War-derived ennui was to make the protagonist as hopeless and hapless as possible, to reflect the flannel-wrapped blinders through which the author now sees the world. To Vonnegut, Earth is a pathetic stage on which man inflicts indignity on himself and then on others. Then they die. So it goes.

On or about page 81, Gideon got a little tired of the fairy-tale language Vonnegut employs. It worked in Harrison Bergeron, but it's a bit of a one-trick pony.

Somewhere along the line, Gideon figured that the inclusion of the starlet, Miss Montana (who exists to provide someone besides the enormous Mrs. Pilgrim for Billy to stick his hefty wang into) was so that, in addition to appealing to SF fans, the book would appeal to horny SF fans. And horny readers in general. And because S.E.X. s.e.l.l.s.

Kilgore Trout, if he existed, would probably be reprinted these days in Amazing.

About a third of the way in, Gideon determined that he would write the review of Slaughterhouse Five in the style of Slaughterhouse Five.

Whatever the book is not, it is, at the very least, a memorable account of the author's feelings toward and memories of those dark last months of the war. It is a poignant counterpoint to all the jingoistic WW2 films that have come out this decade, and perhaps a more suitable epitaph for the millions who died in that conflict. So it goes.

Four stars.

by Cora Buhlert

War is hell: Slaughterhouse Five by Kurt Vonnegut

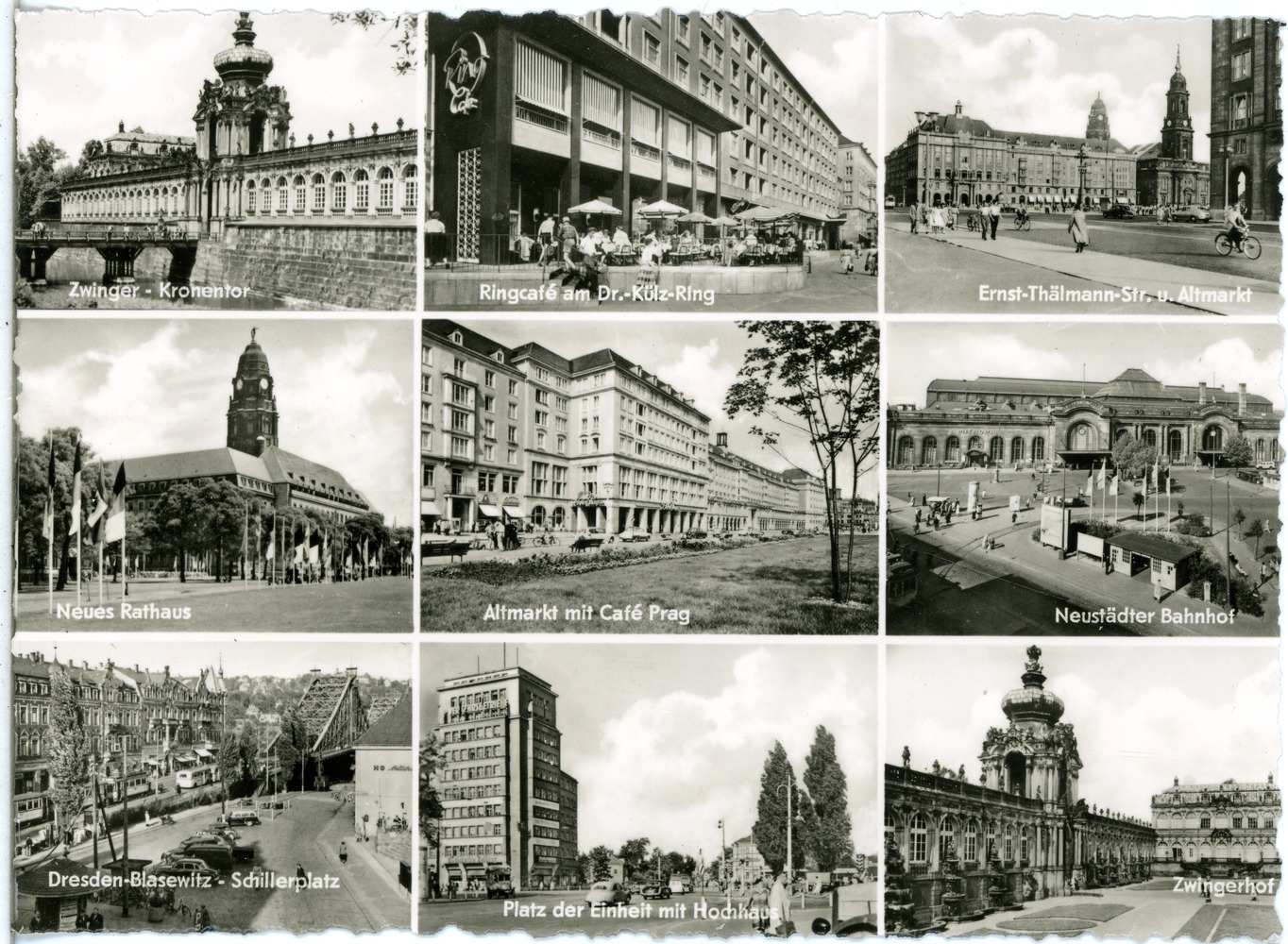

Last month, thousands of people gathered in Dresden to remember the victims of the Allied bombings in the night from February 13 to 14, 1945, the night from Shrove Tuesday to Ash Wednesday and never was a day more aptly named. These memorial gatherings happen every year and while the number of East German officials and politicians attending and the degree of belligerence in their speeches waxes and wanes with the greater political situation (East German officials like using the Dresden bombings for propaganda purposes as an example of the infamy of the West), one thing that remains constant is the number of Dresdeners who come to remember the dead and the nigh total destruction of their city.

I have never seen Dresden before 1945, though my grandmother who grew up in the area told me it was a beautiful city and how much she missed attending performances at the striking Semper opera house, which was largely destroyed by the bombings and is in the process of being rebuilt (The proposed completion date is 1985). However, I have visited the modern Dresden with its constant construction activity and incongruous mix of burned out ruins, historical buildings in various stages of reconstruction and newly constructed modernist office and apartment blocks and could keenly feel what was lost.

I also know survivors of the Dresden bombings such as my university classmate Norbert who witnessed Dresden burning as teenager evacuated to the countryside and who – much like Kurt Vonnegut – was forced to help with the clean-up work and body recovery and wrote a harrowing account of his experiences for the university literary magazine.

Of course, Dresden was not the only German city bombed. Every bigger German city has its own Dresden, that night when entire neighbourhoods were wiped out and thousands of people, the vast majority of them civilians, were killed. For my hometown of Bremen, the night was the night of August 18, 1944, when Allied bombers destroyed the Walle neighbourhood next to Bremen harbour (while miraculously missing most of the harbour itself, similar to how the bombing of Dresden miraculously missed the industrial plants on the outskirts of the city). My grandfather, a retired sea captain, lived in the Walle neighbourhood. He was one of the lucky ones and survived, though his home in a housing estate for retired seafarers was destroyed. I remember sifting through the still smoking rubble of Grandpa's little house with my Mom the next day, looking for anything that might have survived the bombs and the firestorm and finding only two bronze buddha statues that Grandpa had brought back from Thailand. These two buddhas now stand guard in my living room, the war damage still visible. Meanwhile, the street where Grandpa once lived no longer exists on modern city maps at all.

This is the perspective from which I read Kurt Vonnegut's latest novel Slaughterhouse Five, which uses science fiction as a vehicle for Vonnegut to describe his experiences as a prisoner of war who survived the bombing of Dresden and – like my classmate Norbert – never forgot what he saw that night and in the days that followed.

The result, much like the contemporary Dresden with the burned out ruin of the Church of Our Lady overlooking a parking lot and a hyper-modern restaurant and entertainment complex sitting directly opposite the newly restored Baroque Zwinger palace, is jarring and incongruous. Vonnegut's protagonist is Billy Pilgrim, an American everyman whose suburban postwar life is disrupted when he is abducted by aliens and becomes unstuck in time, forced to revisit the bombing of Dresden over and over and over again.

Slaughterhouse Five is not so much a novel, it is a metaphor for the trauma of war, a trauma that still hasn't subsided even twenty-four years later but that keep rearing its ugly head again and again. Many veterans report having flashbacks to particularly traumatic experiences during the war – any war. But while those flashbacks are purely psychological, poor Billy Pilgrim physically travels back in time to the worst night of his life over and over again.

Barely a blip on the radar

The bombings of World War II loom large in the collective memory of people in Germany and the rest of Europe, yet they are comparatively rarely addressed in contemporary German literature. Der Untergang (The End: Hamburg) by Hans Erich Nossack from 1948, Zeit zu leben und Zeit zu sterben (A Time to Love and a Time to Die) by Erich Maria Remarque (who was not even in Germany, but sitting high and dry in Switzerland during WWII) from 1954 and Vergeltung (Retaliation) by Gert Ledig from 1956 are some of the very few examples. It's not as if World War II plays no role in German literature at all, because we have dozens of war novels. However, these are all tales about the experiences of soldiers on the frontline, not about the civilians getting bombed to smithereens back home. Most likely, this is because war novels focus on the experiences of men (and note that both Slaughterhouse Five and Remarque's A Time to Love and a Time to Die focus on soldiers experiencing bombings and air raids) and the experiences of men are deemed important. Meanwhile, the people who suffered and died during the bombing nights of World War II were mainly women, children, old people, sick people, prisoners of war, concentration camp prisoners and forced labourers and their experiences are not deemed nearly as relevant.

Considering how utterly destructive the bombing of Dresden was, it's notable that it is barely a blip on the radar of German literature in both East and West. Erich Kästner's memoir Als ich ein kleiner Junge war (When I was a little boy) touches on the bombing of Dresden, where Kästner grew up, though the book is not about the bombing itself, which Kästner did not experience first-hand, because he was living in Berlin at the time. And for the twentieth anniversary of the Dresden bombings, Ulrike Meinhof, one of the brightest lights of West German journalism, penned a scathing article for the leftwing magazine Konkret, condemning Winston Churchill and Royal Air Force commander Arthur Harris for ordering the attack on Dresden under false pretences. "Was Winston Churchill a war criminal?" the cover of the respective issue of Konkret asked, while quite a lot of readers wondered why this was even a question.

So should Slaughterhouse Five, a work by an American author, albeit one who witnessed the bombing of Dresden first-hand, become the definitive account of the destruction of Dresden and of the bombing nights of World War II in general? I hope not, because I want to read more accounts by German civilians about the bombings of World War II. Nonetheless, I'm glad that Slaughterhouse Five exists, as an account about the horrors of war by one who has seen them. I'm also glad that this novel was published in the US, because too many Americans still consider the bombings of cities and civilians during World War II justified. Maybe Slaughterhouse Five will make some of them reconsider, especially since – as I said above – it wasn't just Dresden that was destroyed by bombing. It was also Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Rotterdam, Coventry, Guernica, Hamburg and right now, it's Hanoi. And the next generation's Billy Pilgrim is currently locked up in a bamboo cage in the Vietnamese jungle somewhere, watching the flames over Hanoi turn the sky blood red.

Not a pleasant book at all, but an important one. Four and a half stars.

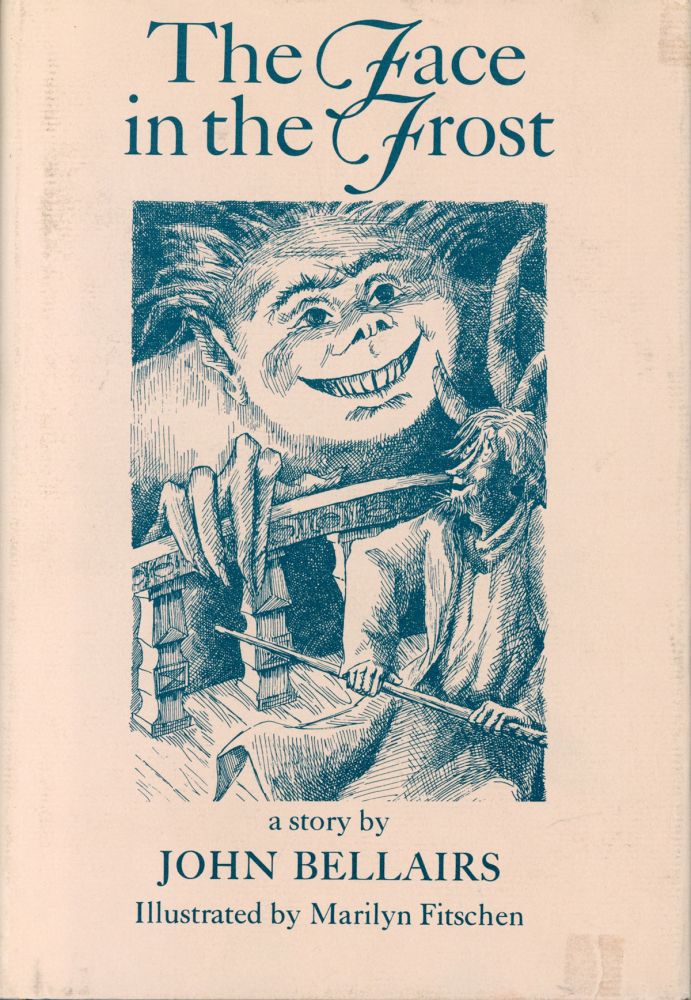

A Tale of Two Wizards: The Face in the Frost by John Bellairs

And now for something much more pleasant. For after a difficult book like Slaughterhouse Five, you need a palate cleanser. Luckily, I found the perfect palate cleanser in The Face in the Frost by John Bellairs, a young American writer currently living in Britain. The Face in the Frost is thirty-year-old Bellairs' third book and his first foray in the fantasy genre.

The novel starts off with a prologue that informs us that this is a book about wizards – just in case readers of Bellairs' previous two books, collections of Catholic humour pieces, are confused – and then introduces us to the setting, two adjacent kingdoms known only as the North and the South Kingdom. Such prologues can be dry and boring, but Bellairs' whimsical humour, which is on display throughout the book, makes them fun to read.

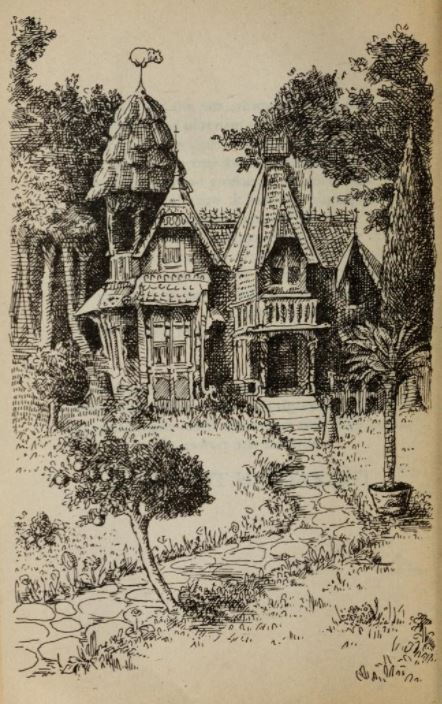

Once the introductions are out of the way, we meet our protagonist, the wizard Prospero ("not the one you're probably thinking of", Bellairs helpfully informs us) or rather his home, "a huge, ridiculous, doodad-covered, trash-filled two-story horror of a house that stumbled, staggered, and dribbled right up to the edge of a great shadowy forest of elms and oaks and maples", which Prospero shares with a sarcastic talking mirror which can offer glimpses of faraway times and places, though mostly, it's just annoying and also has a terrible singing voice.

This first chapter very much sets the tone for the entire novel, humorous and whimsical – with moments of dread occasionally creeping in. For Prospero has been plagued by bad dreams of late, he has the feeling that a malicious presence is watching him and finds himself menaced by a fluttering cloak, while getting a mug of ale from his own cellar. To top off Prospero's very bad day, he finds himself attacked by a monstrous moth that "smells like a basement full of dusty newspapers".

Luckily, Prospero's friend and fellow wizard Roger Bacon – and note that this time around, Bellairs does not inform us, that this is not the one we're thinking of, so this likely is the famed medieval scholar and creator of a talking brazen head – chooses just this evening to drop by for a visit, after having been kicked out of England, when a spell went awry and instead of constructing a wall of brass around the island in order to keep out Viking raiders, Bacon instead raised a wall of glass with predictable results.

As the two old friends discuss the day's events, it quickly becomes clear that something or rather someone is after Prospero and all that this is linked to a mysterious book that Bacon tried to locate on Prospero's behalf. However, it's late at night, so the two wizards go to bed, only to awaken in the morning to find the house surrounded by sinister grey-cloaked figures, sent by a rival wizard. There's no way out – except via an underground river that the two wizards navigate aboard a model ship, after shrinking themselves down to toy size.

A Magical Mystery Tour

What follows is a marvellous, magical quest, as Prospero and Bacon attempt to figure out just who is after Prospero and once they do, how to stop that villainous sorcerer from casting a spell that will plunge the whole world into everlasting winter. On the way, the two wizards encounter such fascinating locations as the village of Five Dials, which turns out to be an illusion, a magical Potemkin village of hollow houses inhabited by hollow people. They also escape all sorts of horrors their opponent sends against them such as a magical puddle that will capture a person's reflection, should they happen to look into it, and of course the titular face that appears in a frost-encrusted window to mock and menace Prospero.

Fantasy is experiencing something of a boom right now, triggered by the paperback release of J.R.R. Tolkien's Lord of the Rings trilogy and Lancer's reprints of Robert E. Howard's tales of Conan the Cimmerian. But while Conan has inspired a veritable legion of other fantastic swordsmen and barbarian warriors from Michael Moorcock's Elric of Melniboné to Lin Carter's Thongor, Lord of the Rings has inspired very few imitators. Until now.

This does not mean that The Face in the Frost is a carbon copy of The Lord of the Rings or The Hobbit. Quite the contrary, it's very much its own story, even though the Tolkien inspiration is clear and was acknowledged by Bellairs. Furthermore, Bellairs' light and frothy tone makes The Face in the Frost a very different, if no less magical experience than Professor Tolkien's magnum opus.

The Face in the Frost is a delightful book, skilfully mixing humour and whimsy with horror and dread, and the illustrations by Marilyn Fitschen help bring the wonderful world of Prospero and Roger Bacon to life. The ending certainly leaves room for a sequel and I hope that we will get to read it sooner rather than later. At any rate, I can't wait to see what John Bellairs writes next.

A wondrous confection of whimsy, horror and pure joy. Five stars.

Society Without Gender…

Another year, another Le Guin. For those tuning in for the first time, my introduction to Le Guin began two years ago, with her novel City of Illusions, which left me disappointed. Last year, I read A Wizard of Earthsea, where finally I saw Le Guin’s potential realized. When I saw she has another book coming out this year, I was interested, but reined in my expectations when I realized The Left Hand of Darkness would take place in the same universe as City of Illusions.

This is book four of the Hainish Cycle, but fortunately, you do not need to read these books in order to understand the story. In fact, I found little connection between this book and the previous one.

The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. Le Guin

Cover by Leo and Diane Dillon

Genly Ai is an envoy sent to the snowy planet of Winter to convince the people to join the Ekumen (a sort of alliance between planets). Winter, or Gethen in their native language, is not as technologically advanced as the rest of the universe. They have yet to build airplanes, let alone a vehicle capable of space travel. Following an outsider’s perspective allows readers to learn about a new culture alongside the narrative main character.

As per my experience with her previous works, Le Guin excels at creating compelling and unique settings. Smaller, intermediate chapters offer folkloric stories from the planet of Winter to further enhance the reader’s understanding of Gethenian culture.

All the characters are human, though the Gethenians differ in one key way. They are completely androgynous except for once a month when they enter their reproductive cycle (known as “kemmer”) where they then shift into either male or female (as in they can either impregnate or become pregnant.) Which role a Gethenian will take on during kemmer is not predetermined and can change between cycles.

This confuses and occasionally disgusts Genly Ai, who regards all characters with he and him pronouns, perhaps because he is male and unable to empathize with or respect anyone who isn’t.

Without gender, Le Guin posits that there is no sexuality, no rape, no war. People who get pregnant are not treated as lesser. Children are raised by everyone, not just the person who gave birth to them. Jobs account for kemmer, giving time off for those experiencing their cycle, and special buildings are set aside for reproduction.

Contrasted with the world we live in today, this book subtly calls out the sexism of our own society, while also exemplifying how we may improve. I was pleasantly surprised by the feminist slant of this book.

Five stars.

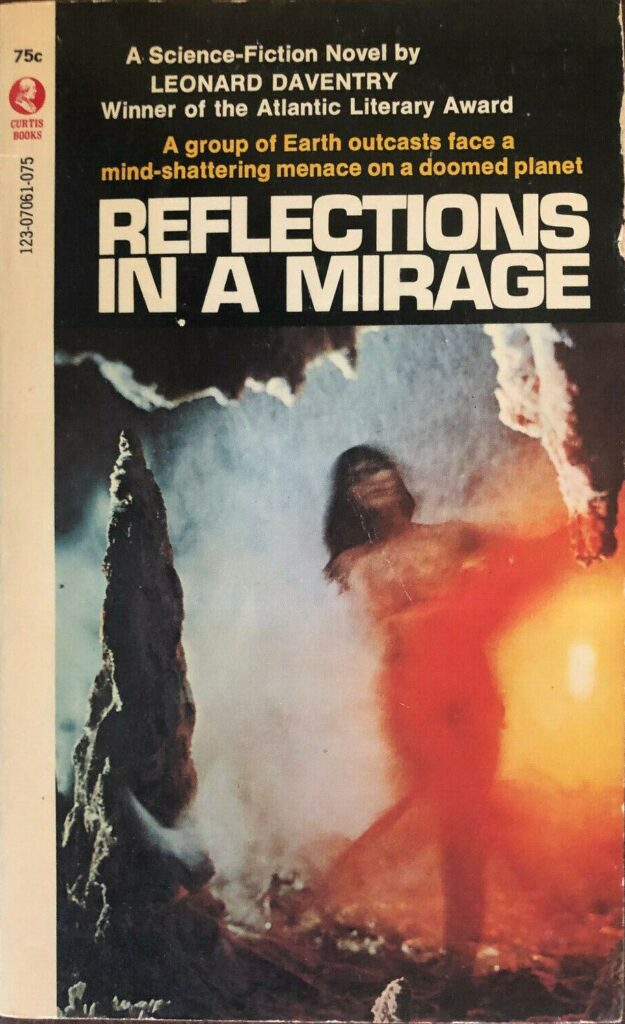

Reflections in a Mirage, by Leonard Daventry

By Jason Sacks

Leonard Daventry is a British science fiction author whose work tends to follow standard pathways – until it doesn’t. As my fellow Galactic companion Gideon Marcus wrote about one of Mr. Daventry’s previous novels, Daventry likes to explore ideas of free love and complex relationships, using familiar set-ups with slightly surprising resolutions.

His latest book, Reflections in a Mirage, is an excellent demonstration of how Mr. Daventry takes on those challenges while delivering his own unique view of the world. Unfortunately, this novel is perhaps overly ambitious for its length. Mirage consequently falls short of the author’s clear goals.

We return to the lead character Daventry established back in 1965 in A Man of Double Deed: Claus Coman is a telepath, a so-called “keyman” who can create connections to minds of both humans and non-humans. Coman is enlisted to join a motley band of outcasts and criminals who journey to one of the many worlds which humanity has discovered among the vast stars: a forbidding but intriguing planet called Sacron. Coman at least has the comfort of traveling with longtime companion Jonl, a woman with whom he’s had a complex relationship.

But just as many British exiles to Australia rebelled against their crew, the group of 50 outcasts rebel against the crew of their space cruiser. A violent, vicious battle kills most of the men who can fly the cruiser, and terrible damage is visited upon the ship. They only have one choice: to land on the planet which is ironically called Paradise 1. Paradise 1 seems to be a desert world, nearly bereft of any life whatsoever, but there are hints the planet may be more complex than it initially seems.

In fact, we get an intriguing revelation towards the end of the book (with a few concepts which will be well understood by Star Trek fans), but I found myself hungering for more context of the deeper story. At a mere 191 paperback pages, I was constantly under the impression that Daventry had to cut out important elements to the story; its brevity leaves the conclusion feeling a bit unsatisfying.

Reflections in a Mirage is at its best when it explores the human relationships it depicts. Coman’s relationship with Jonl is at the center of the story and provides a happy connection where so many of the other connections are tenuous. Daventry spends some time showing Jonl’s relationship with other women on the colony ship – the men and women are partitioned away from each other – and alludes to furtive, loving relationships among the women. There are similar hints about some of the men's connections to each other, and a strong implication that this society accepts a full gamut of sexuality, from polygamy to homosexuality and even to asexuality.

All of that is very interesting, and places this novel firmly in a “new wave” mindset, but there’s just not enough of it to satisfy. Ultimately, Reflections in a Mirage has the potential to be great, but I felt Daventry needed at least 100 more pages to fully illuminate his story.

You’ll probably be more satisfied reading some of the other works in this column. (I do recommend the LeGuin and Vonnegut books.)

3 stars

by Mx. Kris Vyas-Myall

The Cassiopeia Affair by Chloe Zerwick & Harrison Brown

In Redo Valley, Virginia, a radiotelescope complex in the late 20th century hunts for extra-terrestrial intelligence. One night Max Gaby detects a signal coming from Cassiopeia 3579. Inside there is a two-dimensional picture being sent out via binary.

This provides proof of an alien intelligence.

At the same time, conflict is brewing between Russia and China, one that could plunge the world into nuclear war. Is this evidence of intelligent life among the stars the greatest hope we have for peace?

Yes, this is yet another story of Radio Astronomy. These are now becoming as regular in science fiction as space adventures and superhuman mutants, but this stands out as a wonderful example. I believe this is the first fiction from the pair, with Zerwick being primarily a visual artist and Brown being a scientist. Together they have created something masterful.

Although much of the novel is taken up by discussions of scientific theories or information on how to programme radio telescopes, it is raised up by excellent writing and a real understanding of character. Whilst Judith Merrill criticised it for being dull, I never found it so. It was a book I was dying to pick up whenever I got the opportunity. It is a testament to the authors that it never felt dry.

Regarding the characters, it is a huge cast, but one where they all feel considered and with depth, not merely props for discussion. These include Max Gaby as the wide-eyed believer, Barney Davidson the grouchy cynic, Rudolph Calder the Machiavellian hawk and Adam Lurie the disillusioned drunk who is secretly sleeping with Gaby’s wife.

Throughout there are little moments that make it feel real, such as Gaby calling Adam up at 4 am about a possible sighting and Adam grumpily insisting on having his shower and coffee first, or when someone tries to bribe Davidson and he threatens to kill him.

The characters are not perfect either, we regularly change perspective and sometimes see that they are downright unpleasant. But it is made clear we are not meant to sympathise with everyone’s point of view, rather to gain an insight into their motivations.

It also tries to consider the politics of the situation carefully. It demonstrates how different factions will react and what they will want to do with this information. A particularly interesting, if depressing, touch is that the hawks on both sides of the Iron Curtain distrust Gaby as he is a refugee from Hungary in 1956. This element gives it both a sense of excitement and verisimilitude that is often missing from these heavier works.

These kinds of harder science fiction stories are not usually the ones that appeal to me. However, I was enthralled. It may be even more enjoyed by fans of Clarke and Niven and I would not be surprised to see it on the Hugo ballot next year.

Five Stars

by Victoria Silverwolf

Assignment in Nowhere, by Keith Laumer

Cover art by Richard Powers.

This is the third in a series of novels dealing with alternate universes. The first was Worlds of the Imperium. The Noble Editor gave it a moderately positive review.

Next came The Other Side of Time. I thought it was pretty decent, if not outstanding.

Both books featured a fellow named Brion Bayard, a man from our own universe who went on to be an agent for the Imperium, a British/German empire that dominates another version of Earth.

Bayard plays a small but important role in this new novel, but the main character is a man named Johnny Curlon. He's also the narrator. Let's say hello to him.

Johnny is a big, strong guy who lives in Florida and runs a fishing boat. The story starts off with some tough hoods trying to intimidate him, but he deals with them easily. At this point, I thought I was reading one of John D. MacDonald's Florida-based suspense novels, particularly those featuring Travis McGee, a big, strong guy who owns a houseboat.

(If you haven't read them, give 'em a try. They're really good.)

Anyway, we find out this is a science fiction novel when Johnny gets rescued from his floundering boat, which the bad guys have sabotaged, by our old pal Brion. He carries Johnny around in a vehicle that can not only travel between universes, but is able to pass through solid matter and become invisible. Mighty handy little gizmo.

Naturally, Johnny is confused by all this. It seems that he's the key to preventing lots of universes from being wiped out by something called the Blight (capital letter and all.) There are antagonists eager to use Johnny for their own purposes.

At this point, Johnny's knife, which is actually part of an ancient sword handed down to him by his ancestors, gets reunited with another part of the ancient weapon. That's our first hint that this SF novel is going to seem a lot like a fantasy adventure.

Johnny winds up working with a fellow who is very obviously the main bad guy. (Obvious to the reader, anyway, although it's quite a while until Johnny catches on.) They travel to a universe whose only human inhabitant is a stunningly beautiful woman, straight out of a sword-and-sorcery story. She even has a pet griffin, and there's a giant around.

(This middle section of the book reminds me of Robert A. Heinlein's novel Glory Road. That was science fiction disguised as fantasy. This one is fantasy disguised as science fiction, to some degree.)

After leaving that magical place with another piece of the sword, the villain takes Johnny to the universe he wants to rule. It's a place where Richard Lionheart didn't die in battle, but lived to be a weak ruler. He wound up surrendering his kingdom to the French, so France is still in control of England, which is called New Normandy.

(Brion already told Johnny that he was the last descendent of the Plantagenets, so it all ties together, sort of.)

The bad guy's plan would come at the cost of destroying a bunch of universes. (You can't make an omelet without breaking eggs, I guess.) Can our hero set things right? (Go ahead, take a guess.)

In typical Laumer fashion, this is an action-packed yarn that moves at a dizzying pace. It's not as tightly plotted as some, and I'd say it's the weakest book in the Imperium series. The middle section — you know, all that fantasy stuff — seems to come from another novel entirely. There's a lot of pseudoscientific blather trying to explain what's going on, and none of it makes any sense.

Two stars.

by Gideon Marcus

Cover by Leo and Diane Dillon

Nine years ago John Breton nearly lost his wife. Now, a decade later, he and Kate are drifting apart, their knives out at every opportunity, their marriage a fast cooling ember. John has thrown himself bodily into his geological consulting business, and his wife has picked a hobby John has no interest in, befriending Miriam Palfrey, an automatic writer. At a typical crashingly dull dinner party with the Palfreys, characterized by endless sniping, John decides only profound drunkenness will get him through the night.

Whereupon he receives a call:

"You've been living with my wife for almost exactly nine years–and I'm coming to take her back."

Because nine years ago, Kate had died. Two years into their marriage, a stupid fight had compelled Kate's husband to stay home, while she trooped through the night, headed for a party she would never attend, intercepted by a brutal rapist and killer.

John, calling himself Jack at the time, was devastated, wracked with guilt. More than this: he began to be unhinged from time, taking trips weekly to the scene of the crime. Jack resolved to stop Kate's murder, even if it meant rending the very fabric of space and causality.

Two timelines were created: Timeline A, in which Jack led a lonely, monomaniacal life, and Timeline B, in which a sleek and unappreciative John enjoyed his misbegotten wife, the fruits of the labor of his alter ego.

Thus, Jack hatched a plan–move sideways to Timeline B…and fill John's shoes, whether he liked it or not.

But the law of conservation of energy is a hard fact, in the multiverse as well as the universe. Jack Breton's actions threaten not only the rocky relationship of Kate and John, but also the whole of humanity.

According to the book's blurb, this is Shaw's third book, but the first to achieve wide distribution. I don't know what his first book was, but I read his second, Night Walk last year. Between that and his short stories, it was clear Shaw was a gifted author just waiting to grow out of his adolescence.

With The Two-Timers, he has done so.

I picked the book up just before bed and had to force myself to put it down. Eight hours later, it was in my hands again, and it did not leave until I'd finished the story come lunchtime (it was a welcome companion as I waited in the courthouse for a jury duty that never materialized).

The characters are vividly, deeply realized, all of them evolving throughout the story. We initially hate John and sympathize with Jack, but neither of the Bretons is wholly irredeemanble, nor sympathetic. And Kate is no prize to be won; she is an independent entity with her own virtues, failings, and feelings. Shaw reminds me a bit of Larry Niven, drawing people with quick, deft strokes. But Shaw has a sensitive style, working more with emotions than hard science. It's the people that matter in this piece; the SFnal content is exciting, necessary, but secondary.

The pacing in the book is exquisite, from the painful depiction of a marriage gone sour at the beginning, to the arrival of Jack, through the resolution of the resulting triangle. The interspersed scenes of the slow collapse of the physical universe around them are deftly handled, as is the closing in of Lieutenant Blaize Convery, the detective who knows Breton saved his wife nine years ago; he just can't figure out how.

As Lorelei (who picked up the book on my recommendation and tore through it in short order) notes, aside from the poetic writing, the real triumph of the book is that you get so many viewpoint characters, and so many changing perspectives on these characters, and none of it is confusing. It's just masterfully done.

It's a hard book to read in parts. The emotions here are fraught ones, and there are some rather unpleasant (though never gratuitous) scenes. Nevertheless, these are emotions that must be explored, and thankfully, the mystery and the brilliant writing carry you past them, as well as the satisfying resolution of the threesome's story. My only quibble is that the end doesn't quite work, logistically, though it makes sense thematically. And as Lorelei notes, it's a touch rushed.

Nevertheless, The Two-Timers is a terrific work, definitely a strong contender for my Hugo ballot next year.

4.5 stars.

We Americans love a good revolution story. After all, our nation was founded by a rebellion, and the appeal of an underdog throwing off an oppressor has been popular since David threw a rock at Goliath.

C.C. MacApp takes a stab at the theme with his latest book, Omha Abides, a tale of the 35th Century. 1500 years before, the Gaddyl had conquered the Earth. The amphibian aliens did not succeed without a fight, but their advanced technology, particularly their craft-shielding Distorters, proved decisive. Human civilization was shattered, the population reduced to a bare fraction, many of them condemned to slavery. Meanwhile, the Gaddyl build their own fiefdoms amidst the ruins of the human cities and built an interstellar teleport transit hub in Arizona.

Now Earth is a hunting preserve, humanity largely quiescent. The North American continent is home to just 25 million people…and half a million overlord Gaddyl. The humans who are not slaves roam in bands or live in primitive statelets. They have no hope of taking back the planet, until a series of events precipitously brings success in their reach.

Our hero is Murno, a freed man who lives with his family in Fief Bay, once known as San Francisco. A new, cruel lord has ascended to the fief throne, and he has decided that no longer shall free humans be off limits to hunting parties.

At the same time, Murno is contacted by the underground. He is entrusted with three items, two of them Gaddyl, and one of ancient human make, which he is tasked to take east, beyond the Sierras, beyond the mysterious Grove, even past the mighty Rockies, to where the mythical deity named "Omha" waits.

If you had a subscription to the recently defunct magazine, Worlds of Tomorrow, you may have read about half of this book. Victoria Silverwolf reviewed Under the Gaddyl Tree, which comprises about the first third of the book, and Trees Like Torches, which contains bits from the middle. Victoria gave both stories three stars and felt they were competent, but nothing special.

Often, the expansion of stories into a novel results in something less than the sum of its parts. The opposite occurs in this case. Now, instead of just being isolated, mildly interesting adventure stories, now Murno's encounters with Gaddyl, blue mutant humans, a giant grove of telepathic trees, and so on, gird a compelling plot. Humanity shouldn't have a chance against the Gaddyl. But neither should an electron, per classical physics, be able to jump energy levels. But thanks to quantum physics and the Uncertainty Principle, given a short enough period of time, an electron can possess abnormal amounts of energy.

Similarly, a confluence of circumstances makes for a successful rebellion opportunity. Because humanity had been waiting for its chance. The telepathic Blues had spies in pivotal places. There was an underground poised for action. There really is an Omha (and you can guess what its nature is early on, which will also clue you in on how to pronounce the word).

Add the trigger of the Gaddyl getting a bit too complacent and a bit too cruel, as well as the theft of some vital technologies, and a human victory becomes plausible.

The pacing of the book is a little off. Much of the human victory isn't even detailed until the last 25 pages of the book (though it turns out that's not really too short a span; MacApp pulls it off). Also, much reference is made to Murno baffling his alien pursuers with "trail puzzles", a phrase with which I'm not familiar, and whose meaning I still don't apprehend. Occasionally, the story does lapse into conventional adventure fare–more like a tale of the American West than the American future.

But, it's a book with real cinematic quality to it; the scenes in California were particularly resonant for me, a Golden State native. The Gaddyl are portrayed perhaps a touch too human, but I appreciated the range of types, from scoundrel to honorable enemy. And as an American, I suppose I've got as much a soft spot for overthrowing tyranny as anyone.

Four stars.

by Mx. Blue Cathey-Thiele

Last year's pairing of E.C Tubb and Juanita Coulson's has gotten an encore. In fact, both novels are sequels. My esteemed colleague and editor had favorable reviews of both, so I was excited to read them:

Ace Double H-77

Derai, by E. C. Tubb

Earl Dumarest, the itinerant interstellar provocateur and do-gooder from The Winds of Gath returns in Derai, hunting news of Earth. On his way he takes a job escorting the Lady Derai of the House of Caldor back to her family on the planet Hive. He soon determines that Derai is a telepath. Her father sent her to the college of Cyclans to treat the constant fear and nightmares brought on by hearing the minds of those around her. Derai ran away from the college, where Cybers (once-humans with emotion and sensation excised who now can connect to a collective mind) wanted to use her genetics, turning her into a mindless vessel to bear telepathic children. Her home planet has its own risks – her uncle wants to take over the House, planning to assassinate her father and half-brother, and marry Derai to her cousin to gain legitimacy.

Dumarest keeps much of his thoughts to himself, both from the other characters and the reader, but cannot keep his developing feelings for Derai from her telepathic ability. He carries himself as a man who has seen too much. He inspires loyalty, and in those he has helped that is understandable, but it also comes from some who have only just met him. One man he meets through a mutual friend takes the chance of being burned to death to get a blade to Dumarest in a deadly maze arena.

Dumarest almost seems to resist the plot, needing to be pushed into each new quest. At times, his struggle as a character made him feel like a disparate individual, one side grim and withdrawn, another altruistic at great cost to himself; it's as if author Tubbs had two distinct directions for the novel in mind, and was unable to find the balance between them. Dumarest's staid demeanor only allows him to rebuff so much, and he is, if reluctantly, still prompted to aid disenfranchised travelers, save a gambler from himself, and compete in a tournament to prolong the head of Caldor House's life. Each time he intends to leave the House to its own devices, his feelings for Derai bring him back.

Tubb has a lurid, graphic style of description. It's equally evocative of beauty and violence. In a particularly unsettling set of scenes, Dumarest barely escapes being eaten alive like his companions by bird-sized bees. For how memorable the depictions of the insects were, I anticipated them playing a larger role in the overall story. The scenes stuck with me for several days due to the excessively grisly details.

Something else that ate at my brain: thanks to medical advancements and travel stasis Dumarest and Derai are chronologically far older than they seem, but Derai was described as childlike far too often for my liking. Tubb could have left it at one use of "nubile".

3 stars

The Singing Stones, by Juanita Coulson

Geoff is a member of the Federation, the galactic government introduced in Coulson's Crisis on Cheiron. He embarks on what could be a suicide mission to the protectorate of Deliayan, Pa-Lüna. Both humans and Deliyans have been exploiting the people of Pa-Lüna, tricking them into indentured servitude. When a man is murdered right in front of him over a stone, Geoff investigates, finding the stone in question has strange, enchanting properties. He and Tahn, a Pa-Lünan, set out for the protectorate, and they meet Nedra, priestess of a mysterious goddess.

From the outset, he is on a clock: a past planetary mission left his team dead, and him with the lingering impacts from a past poisoning that flares, causing him pain and debilitating him with growing frequency. The nature of his sense of duty and outlook, framed by his limited lifespan, is compelling.

Geoff is a skeptic, both of motive and means. He views the people of Pa-Lüna with a mix of respect and condescension, but Geoff witnesses the tangible effects of the stones of song. They induce a euphoria and they, or their "goddess", can heal the sick and injured and strengthen her followers over time. Does the Goddess bestow gifts freely or are her worshipers trading one form of servitude for another, framed in a softer light? Are the powers of the Stones and the goddess's telepathic messages divine or an advanced, but still mortal mechanism?

I appreciated the exploration of what is becoming a new trend in sci-fi–rejecting overt military intrusions and favoring a system that furthers a newly-contacted culture's sovereignty. It's not a bad direction to go, though authors vary in degrees of patronizing the native people of these worlds, from treating them roughly as equals to regarding them as "primitive" beings who need protecting. And it does say something that it takes someone from outside the system to truly put things in motion, no matter how long change has been brewing. Having the fight be against not just an alien threat but also a human, institutional threat asks if human expansion is truly helping, needs tempering, or if it is causing more harm in the end.

All in all, a solid book. Had I not recently read several other books with a similar premise I would have liked it even more. However, I can't fault Coulson for the trends of this year. She created a rich tapestry and I would be happy to explore her worlds and characters in future stories.

4.5 stars

by Mx. Kris Vyas-Myall

In Watermelon Sugar by Richard Brautigan

I occasionally like to check out the authors I hear are very hip right now. It meant I read the excellent Last Exit to Brooklyn and the less great Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up To Me.

Richard Brautigan is one I have heard praise heaped on over Trout Fishing in America but the title put me off (my father talks enough about it!) When I heard he had a more fantastical novel coming out this year I made sure to get a copy.

I am not sure what I was expecting but this book is weird!