by Gideon Marcus

Back in the saddle again

It's been a long time since the halcyon days of the early '50s, when Galaxy was setting the standard to beat, ushering in the Silver Age of Science Fiction (along with the more avante garde F&SF). But now that editor Fred Pohl has collapsed his empire to just two mags, it seems he can afford to be more picky. Indeed, IF is unusually good this month, and the April 1968 issue of Galaxy is by far the best I've read in a long time, and a strong contender for best magazine of March.

by Gray Morrow

Brave new worlds

Goblin Reservation (Part 1 of 2), by Clifford D. Simak

Simak is back with a odd brew of a story, perhaps in the same universe as Here Gather the Stars, as reference is made to a Wisconsin transit station. Eschewing (for the most part) his usual pastoral motif, instead we get the first installment of the book-length adventure of Peter Maxwell, professor at the Time University in North America. At least he was. It seems that, while on the way to do fieldwork on the planet of Coonskin, Maxwell was duplicated. One of him went on to his intended task. The other ended up on a crystalline, roofed-over planet. This world is some 50 billion years old, its inhabitants little more than ghosts, and they possess the knowledge of two universes since they lived through the last cosmological crunch and survived the most recent "Big Bang".

This latter Maxwell is the one we follow, since the other one died in a traffic accident upon arriving home. Now, Maxwell is officially dead, out of work, and at loose ends. Add to that there seems to be conspiracies, both human and alien, to get the secrets of the crystal planet from him, and things get very hot indeed.

That would be a twisty enough tale in and of itself. Throw in the existence of fairies and ghosts (they've been around all along, but now they're acknowledged creatures who live on reservations) as well as working time travel (one of the main characters is Alley Oop, a brilliant Neanderthal), and things are complicated to the extreme!

by Gray Morrow

And yet, somehow Simak makes it all work. It's an unusually humorous story, though the Morrow illustrations are perhaps too comic, and I tore through the half novel in short order.

I am looking forward to seeing where this all goes. Four stars.

The Riches of Embarrassment, by H. L. Gold

Why does Miss McGiveney always seem to happen upon her neighbors at the most embarrassing moments? It may just be her superpower.

This slight tale in particular feels like vintage Galaxy, perhaps because it's written by the magazine's first editor. I hope Fred Pohl edited the story savagely…what's good for the goose is good for the gander.

Three stars.

Brain Drain, by Joseph P. Martino

by Dan Adkins

Tom Harrison, a field agent of Intelligence Imports Incorporated, is in Thailand searching for a particular kind of student, and he thinks he has his target in high school graduate Manob Suravit. It turns out that Triple-I is on the hunt for brilliant PhD candidates, and apparently there aren't enough in America (and/or perhaps there is value in recruiting from beyond our shores).

At first, I thought it would turn out Harrison was looking for folks with psi powers–I was glad to find the object of his search was more mundane. Most of the story is excellent, redolent with such authentic color that I have to think Martino has spent time in Thailand.

The problem is the ending, where Harrison convinces the local schoolmaster to be happy about the loss of promising students. Not so much the reasoning, but the near-polemic way the reasoning is delivered. What could be a thoughtful piece, with shades of gray woven in (as the story appeared to promise earlier on) becomes something more suited for Analog. Along the lines of "Hey, sure we take your smart kids, but you weren't using them, and you've still got plenty."

A missed opportunity. Three stars.

Sword Game, by H. H. Hollis

A bored middle-aged topologist and a grubby would-be Gypsy team up with their tessaract-based circus show. Said mathematician shoves his partner into a cylinder of fuzzy time and space and stabs her vividly, but harmlessly, with a sword while the audience marvels.

But said topologist bores of this, too, and the result is truly macabre (though ultimately happy).

Three stars, but I could see someone going to four.

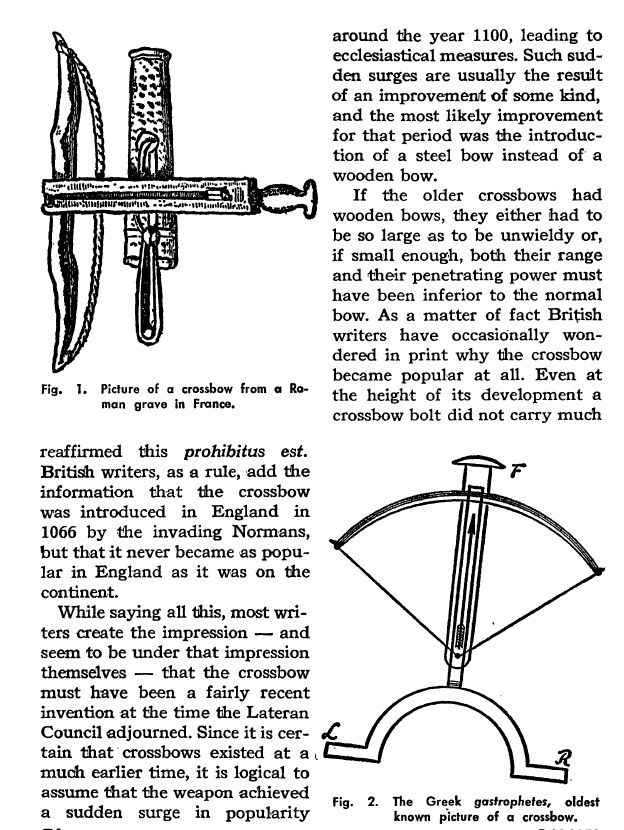

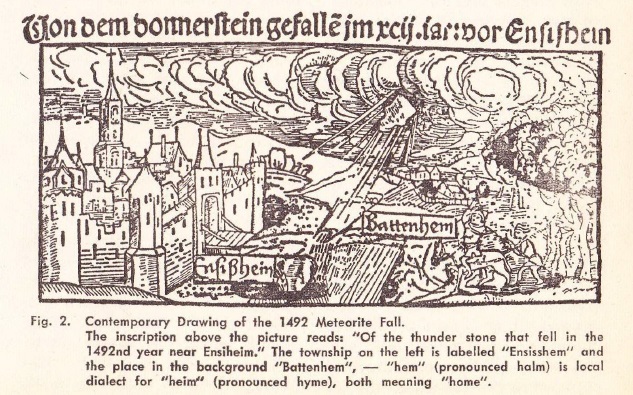

For Your Information: The Devil's Apples, by Willy Ley

Willy Ley offers up a short, but interesting piece on potatoes. Not much to say, really. Three stars.

Touch of the Moon, by Ross Rocklynne

by Dan Adkins

What an odd piece this is, about a romance broken when one of the partners goes to the moon. Gravity has an irrevocable effect not only on the body, but also the psyche. But happily, loosing one's ties to Earth is ultimately good for the species if it ever wants to claim the stars.

This could have been a good story, but it's written far too amateurishly and with too implausible a premise. The former is surprising given that Rocklynne dates back to the Golden Age. On the other hand, I haven't seen hide nor hair of him since I began reading SF regularly (1954), so perhaps he's out of practice.

Two stars.

The Deceivers, by Larry Niven

by Jack Gaughan

Our old pal Lucas Garner is back, this time with a shaggy dog story about the first fully automated restaurant that opened in 2025.

Niven has a real knack for creating whole worlds with a few strokes. He also joins multiple time periods with ease: Lucas Garner was born in 1939, so he is our contemporary. He lives in the 2100s, and he reminisces about the 2000s. Thus, his stories have touches of the futuristic as well as the familiar.

Four stars.

Galaxy Bookshelf, by Algis Budrys

I don't often comment on Algis Budrys' column, but this time, he has some important things to say…and a friend named Brian Collins (who has his own commendable 'zine) did an excellent job of summing it up while adding his own observations:

Algis Budrys dedicates the whole review column to Dangerous Visions, giving us a review I'd say is about 1,500 to 2,000 words long. Budrys has shown us before that he's one of the more "literate" people in the field, but he has a unique challenge with Dangerous Visions, a book he both highly recommends but is highly mixed on as far as its content goes.

He argues pretty well as to why this is a major work in the field and why you should get yourself a copy, despite a lot of the stories therein not holding up to scrutiny. It helps that he and I mostly agree on what works and what doesn't (I'm admittedly one of the few people who liked the Farmer), and it pleases me in a morbid way to find that I'm not the only one who was incredibly disappointed by the Sturgeon. But Budrys notes that while the bloated pseudo-lecture from Sturgeon is a failure, and far under Sturgeon's caliber, it works as a sort of counter-piece to the Emshwiller, which, as Budrys says, feels more like a classic Sturgeon story than the Sturgeon we got. Taken together, these two contribute immensely to a narrative that Harlan Ellison is trying to put forth with the book.

Will Dangerous Visions kick off a new movement in SF? No. We had already seen stuff published in F&SF and New Worlds that would have made fine contributions to Dangerous Visions. This book does not present a brave new world like Ellison claims, but rather as Budrys argues it serves as an essential reminder that change is inevitable and that the field has been changing and will continue to change. No doubt 50 years from now Dangerous Visions will be remembered for the best stories between its covers, but also as a historical artifact—a portrait of a genre in the midst of change, and change is often violent and unpretty.

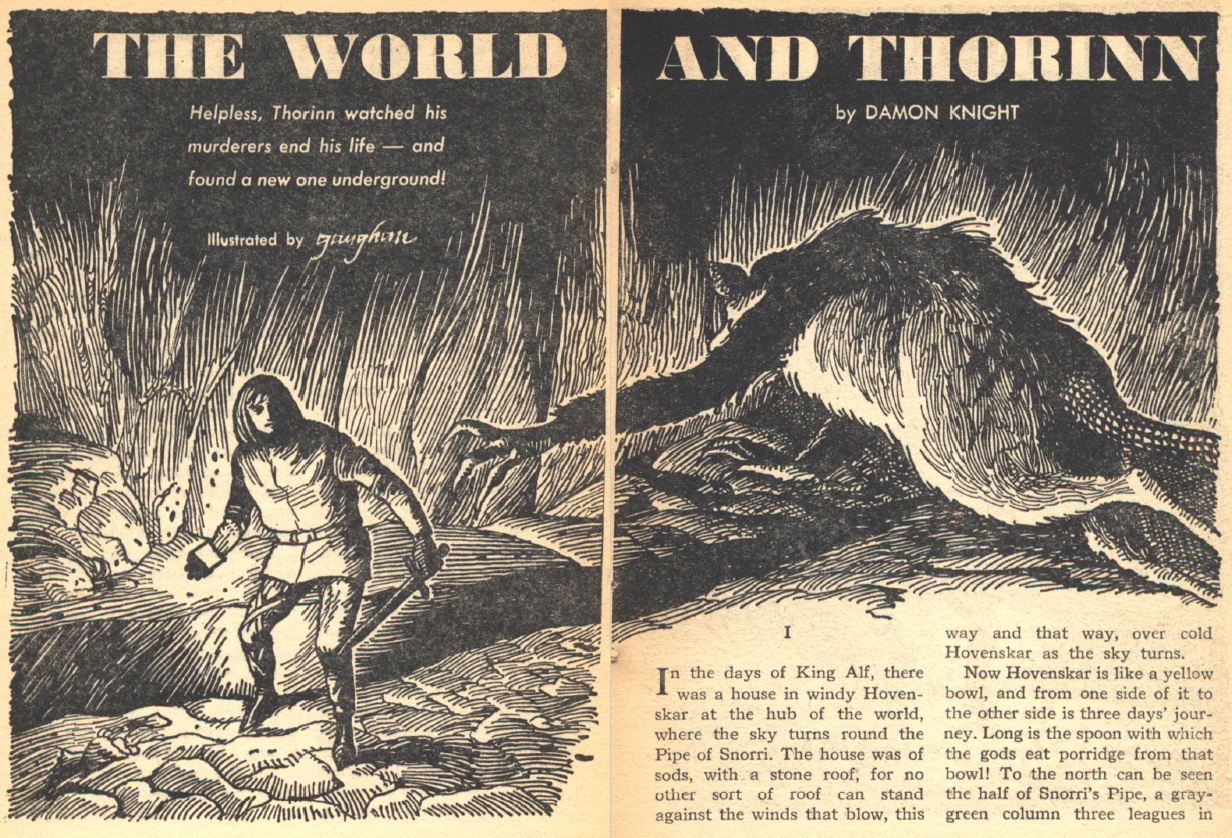

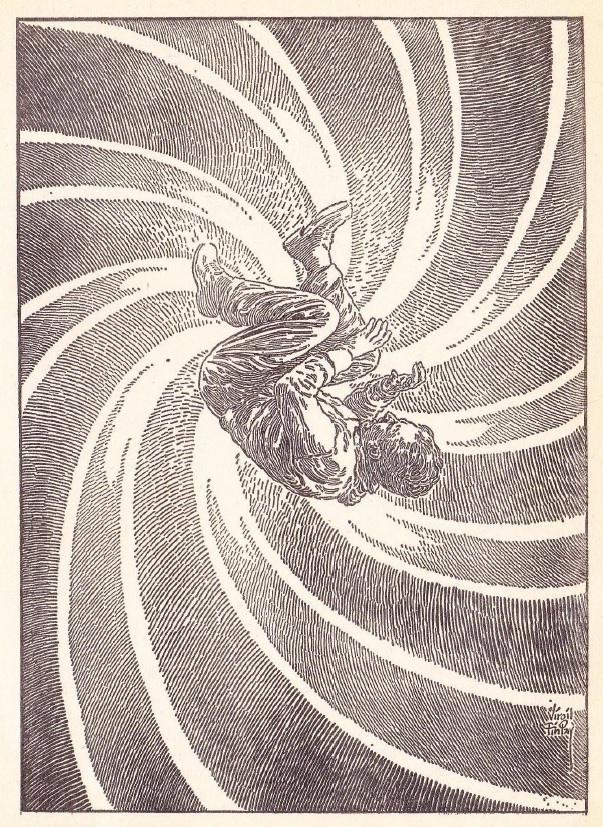

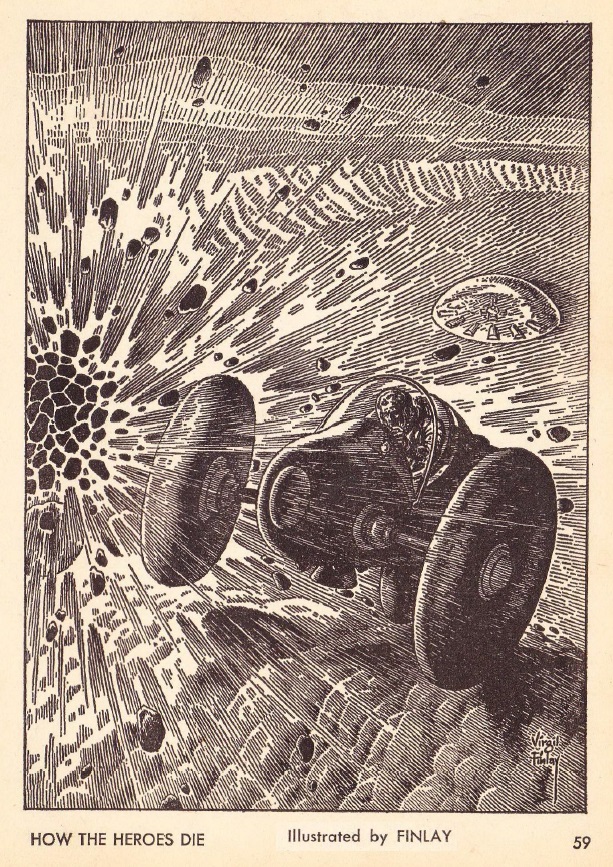

The World and Thorinn, by Damon Knight

by Jack Gaughan

Finally, Damon Knight begins what looks like the first part of serial in all but name. Thorinn is a human raised by trolls in a primitive, Scandinavianesque, not-quite-fantasy world. When calamity befalls his family, they throw him down a well to appease the god Snorri. Thus begins the first of Thorinn's subterranean adventures.

The first few pages are a bit slow, particularly when scenes are repeated from two different viewpoints (I really dislike that style), but the rest makes for an excellent puzzle story, written in a fine, almost Vancean style.

Four stars, and the anticipated book may rate higher.

The Other Show

Between the Simak and the Knight (both fantasy-tinged pieces), we have a couple of open promises. We also have something of a new style: there's a lot more sex in this issue than I've seen recently in Galaxy. Is Pohl taking a page from F&SF's book? Or has the New Wave simply caught up to the Guinn publishing enterprise?

Either way, I like it. More, please!

Don't miss the news — a new episode of KGJ's weekly round-up is being broadcast right now!

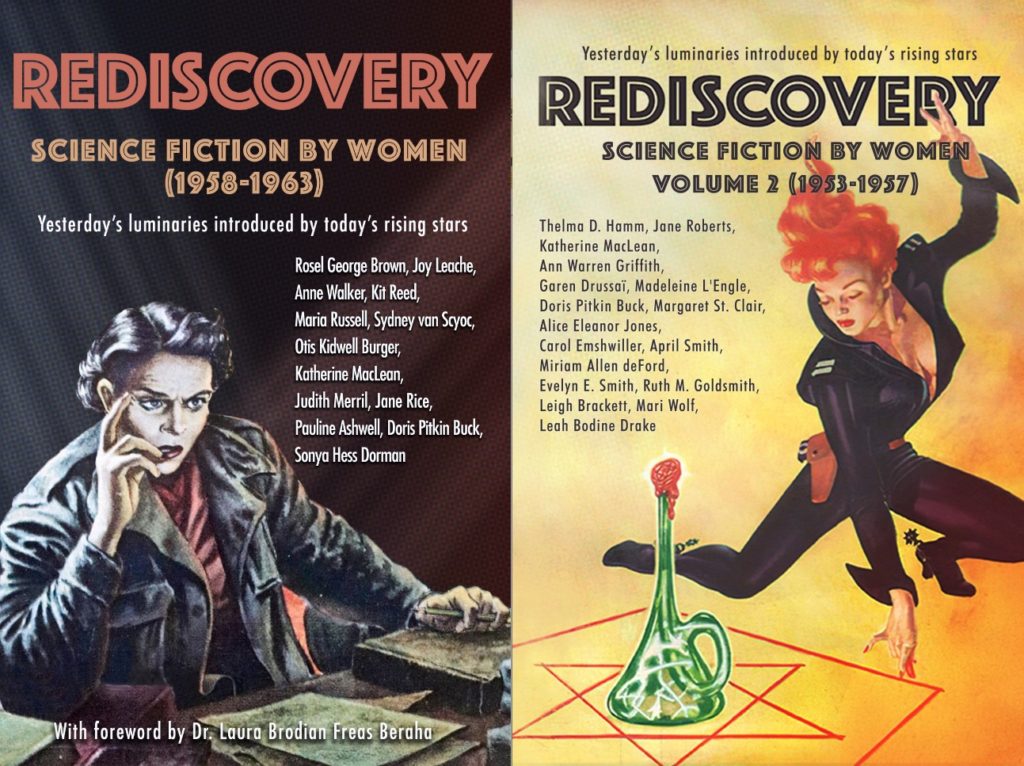

![[March 6, 1968] Trend-setter (April 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/680306cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 16, 1968] Worthy programming (February 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/680110cover-672x372.jpg)

![[July 8, 1967] Family lines (August 1967 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/670710cover-672x372.jpg)

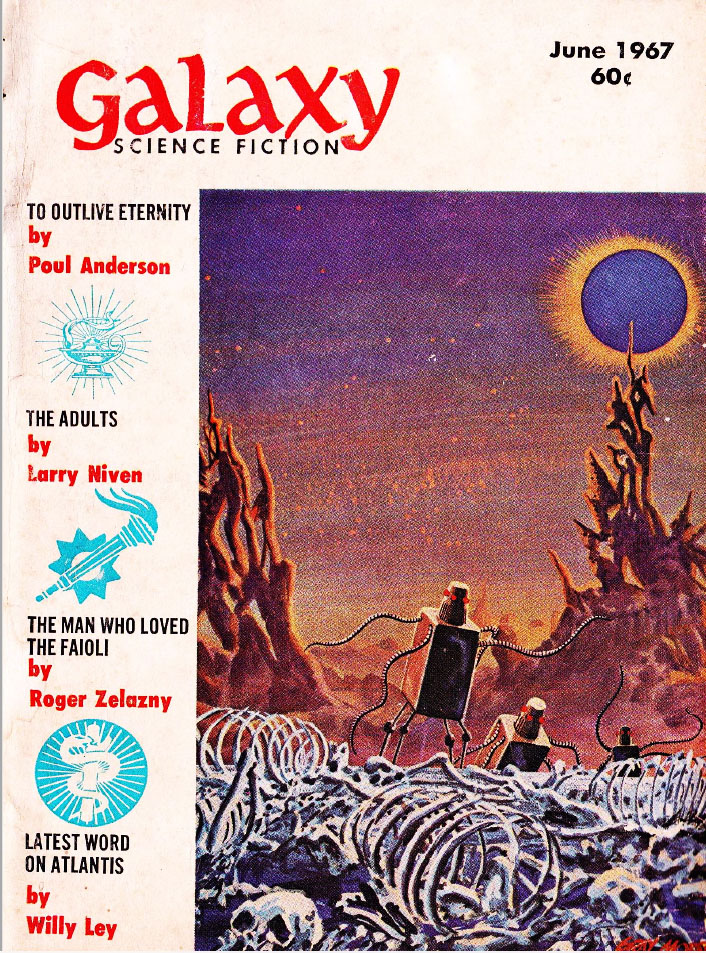

![[May 12, 1967] There and Back Again (June 1967 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/670512cover-672x372.jpg)

![[March 10, 1967] Mediocrités, Slayer of Magazines (April 1967 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/670310cover-672x372.jpg)

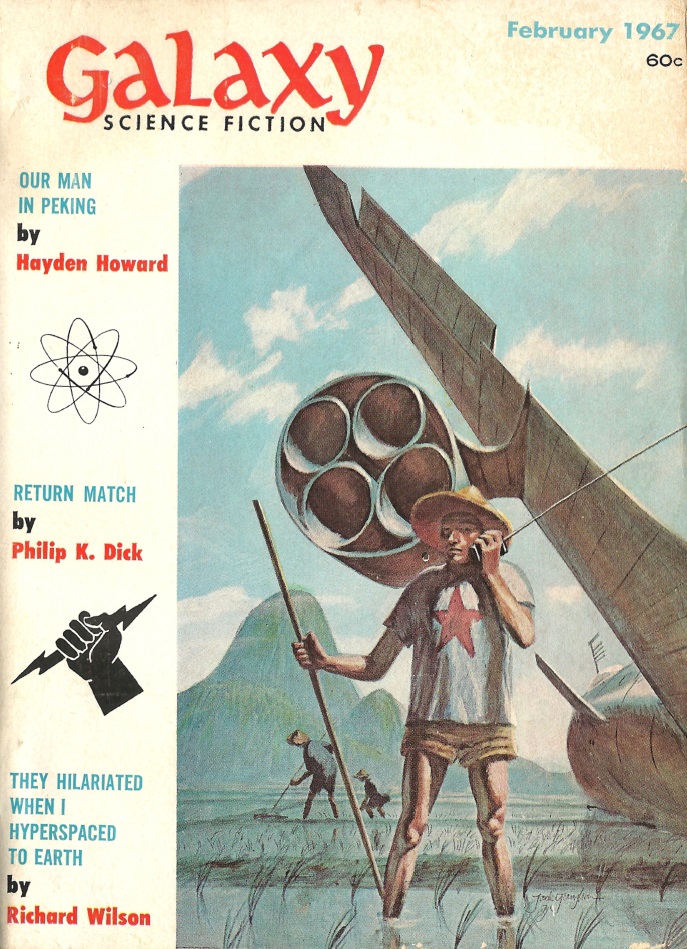

![[January 10, 1967] Return to sender (February 1967 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/670110cover-672x372.jpg)

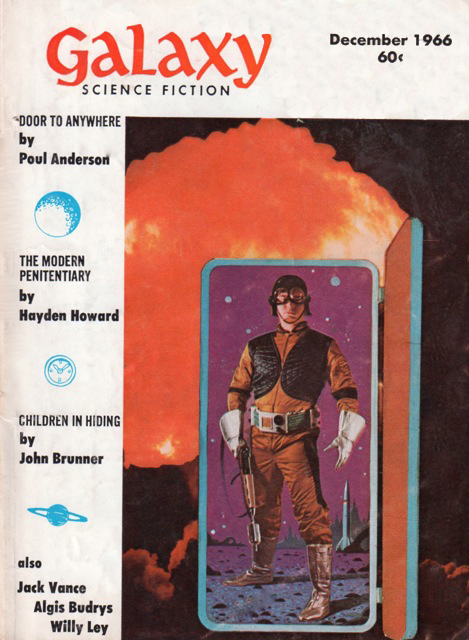

![[November 12, 1966] A Family Tradition (December 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/661112cover-469x372.jpg)

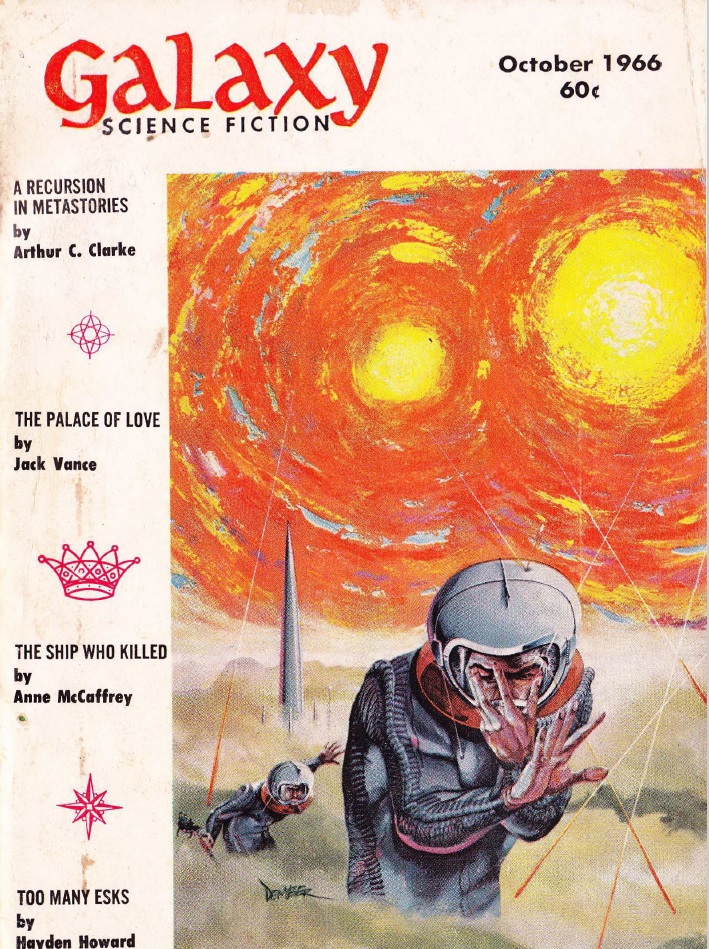

![[September 14, 1966] All the Old Familiar Places (October 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/660912cover-672x372.jpg)

![[July 8, 1966] South Pohl (August 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/660708cover-672x372.jpg)

![[May 10, 1966] Rocky Jaunts (June 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/660510cover-672x372.jpg)