by Victoria Silverwolf

Science fiction writers often have to deal with things on a very large scale. Whether they take readers across vast reaches of space, or into unimaginably far futures, they frequently look at time and the universe through giant telescopes of imagination, enhancing their vision beyond ordinary concerns of here and now.

(This is not to say anything against more intimate kinds of imaginative fiction, in which the everyday world reveals something extraordinary. A microscope can be a useful tool for examining dreams as well.)

A fine example of the kind of tale that paints a portrait of an enormous universe, with a chronology reaching back for eons, appears in the latest issue of Worlds of Tomorrow, from the pen of a new, young writer.

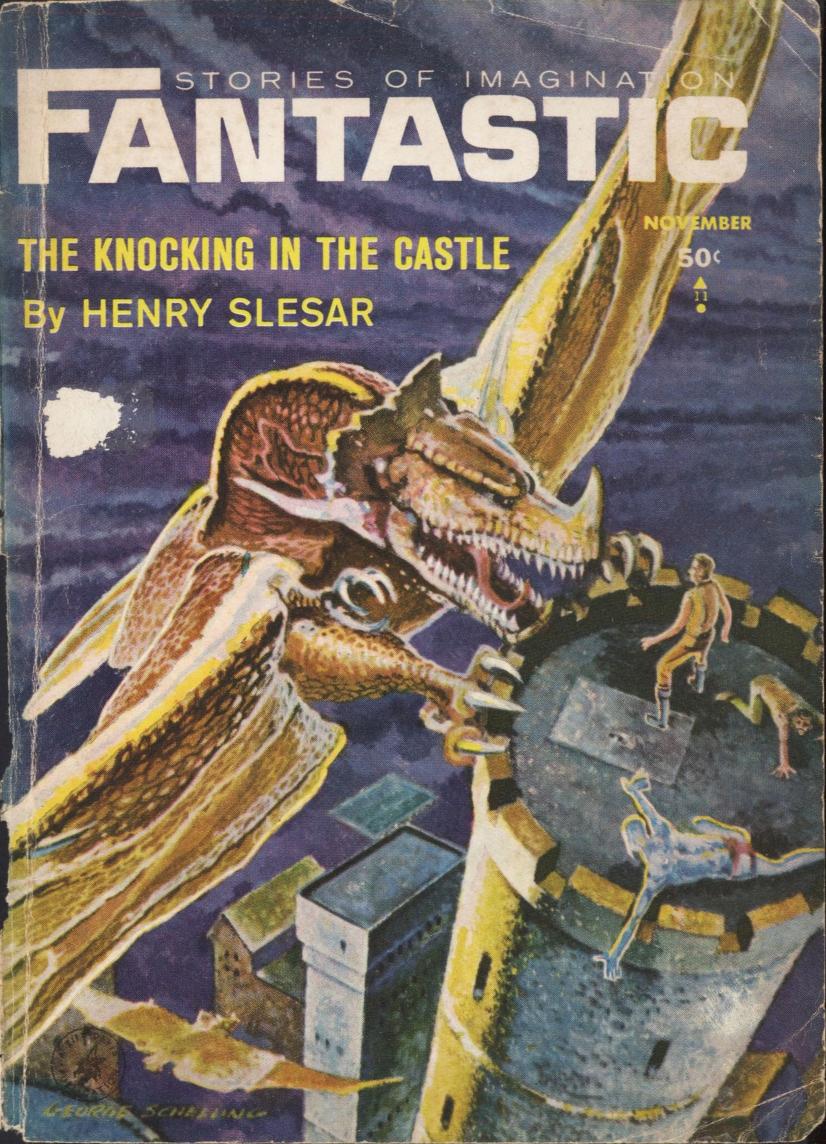

Cover art by George Schelling

World of Ptavvs, by Larry Niven

Illustrations by Jack Gaughan

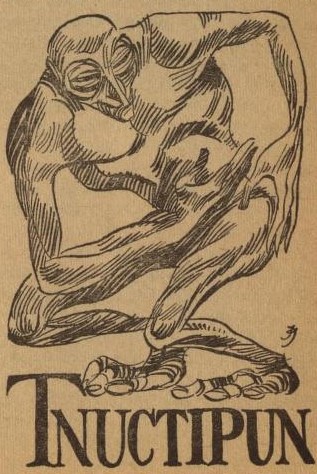

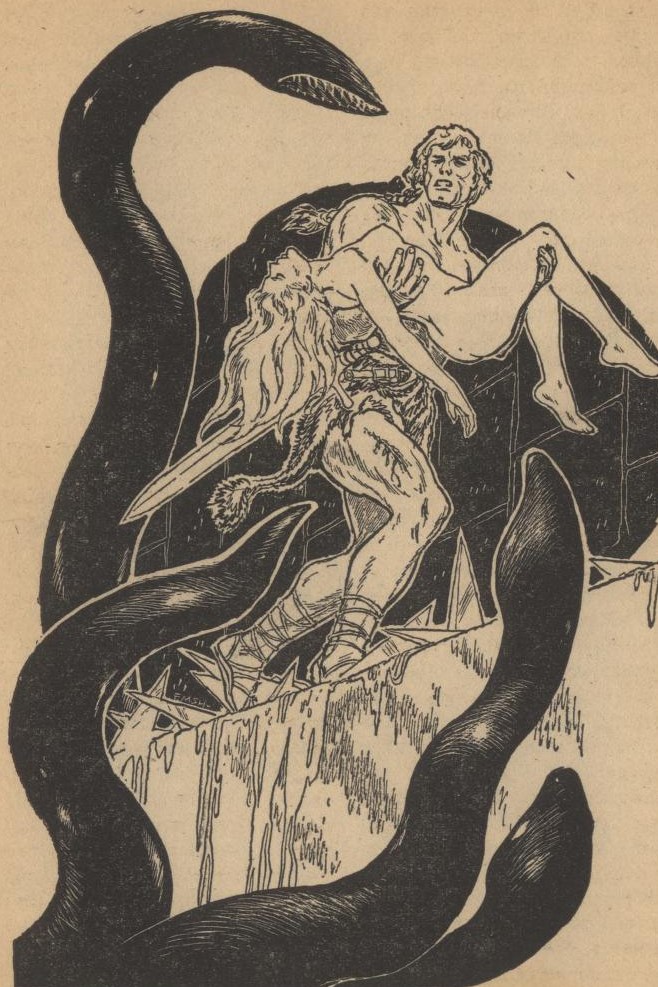

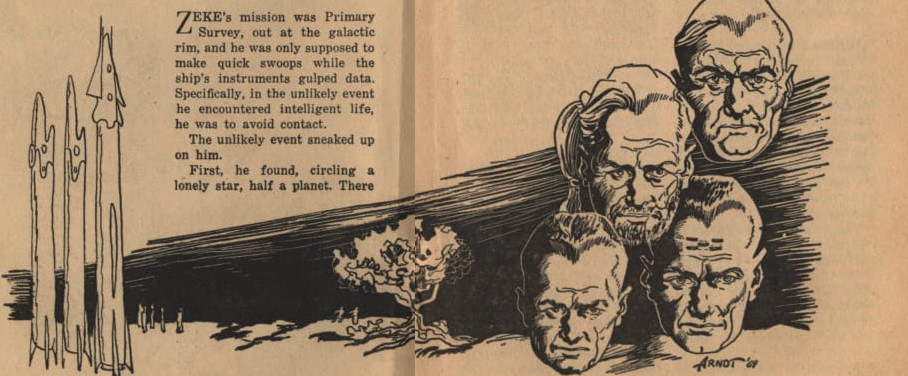

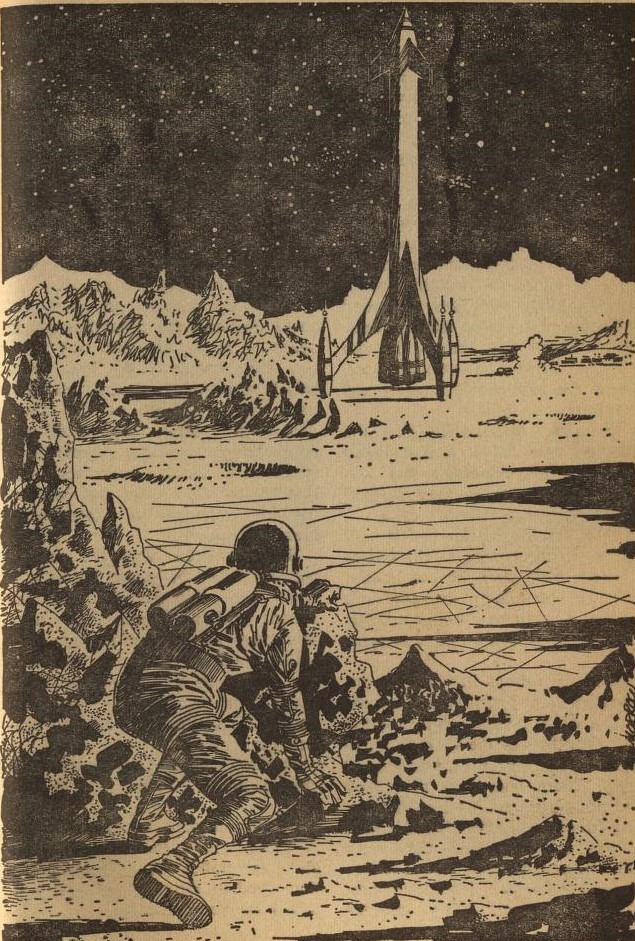

Our story begins about two billion years ago. The character shown above is a member of a telepathic species with the power to enslave other sentient beings with their minds.

An example of a slave species that doesn't play much part in the story.

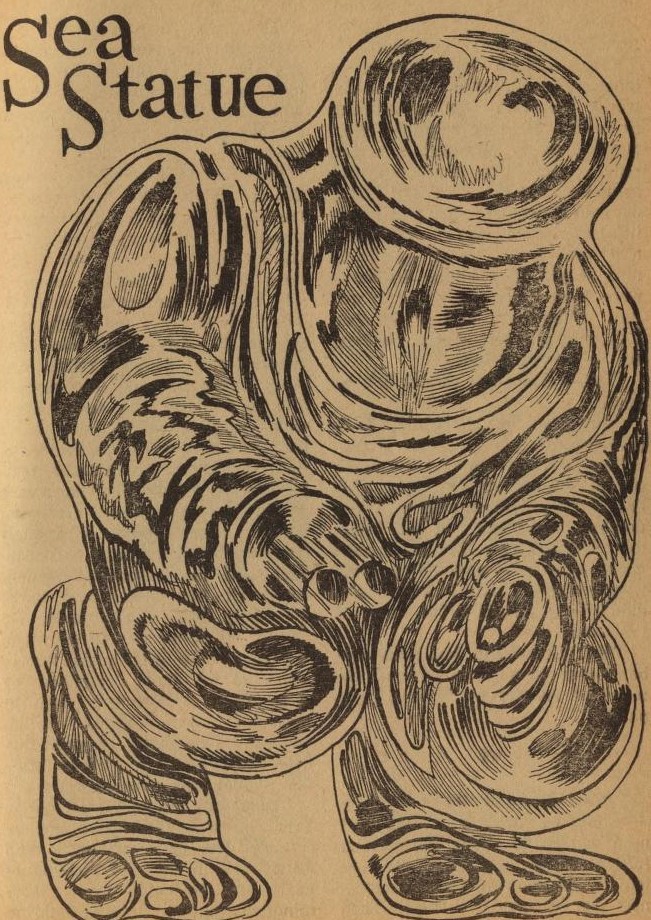

This slave species, on the other hand, has a big impact on what happens to its masters.

Kzanol the Thrint has a problem. On his way to the homeworld in his starship, the engine that allows it to make long-distance voyages explodes. The rest of the ship is unharmed, but Kzanol is stranded. Fortunately, he has a suit that slows time down to a crawl for the wearer. He can't reach his native planet with the power his ship has left, but he can crash into an uninhabited planet, where yeast is grown to feed slaves, after a couple of centuries. He stashes some valuables into a spare suit, puts on the other one, programs the ship for the slow journey, and goes into stasis, expecting to be rescued once enough time has gone by.

Kzanol in the stasis suit.

Cut to Earth, in a future of flying cars and interstellar travel. Larry Greenberg (now where have I seen that first name before?) is a telepath. Compared to an average Thrint, he has hardly any ability at all; but it's enough to get him a job communicating mentally with dolphins. This is really just a stepping stone to a real career of reaching the minds of aliens discovered on the planet humans call Jinx.

Scientists who have just invented a time-slowing device — sound familiar? — realize that the so-called Sea Statue, an ancient object found at the bottom of the ocean, is really an alien inside a similar stasis field. By placing it inside their own gizmo, they can deactivate it. Larry is along to pick up the thoughts of the alien. This works much too well.

Kzanol's mind takes over Larry's body. Although he still has human memories, he thinks he is really a Thrint, lost on a world of ptavvs (beings without telepathic powers.) He also believes that he is trapped in the body of a ptavv himself, because he is unable to control the inhabitants of the planet with his mind.

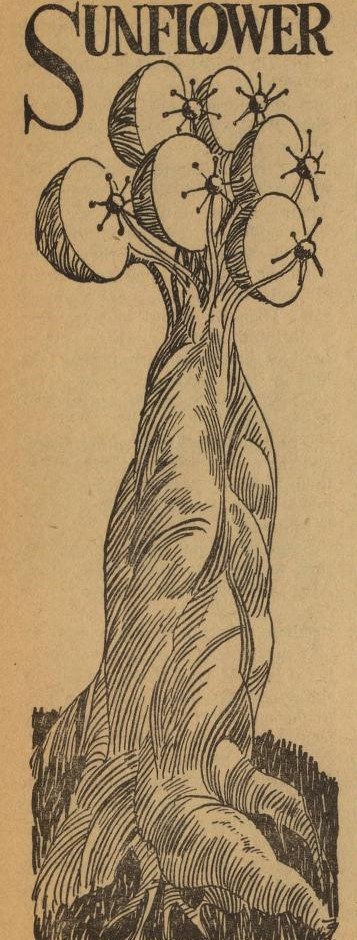

One of several genetically engineered species Larry/Kzanol remembers, adding greatly to the feeling of a richly imagined background. These are giant plants that use solar power as a defense mechanism.

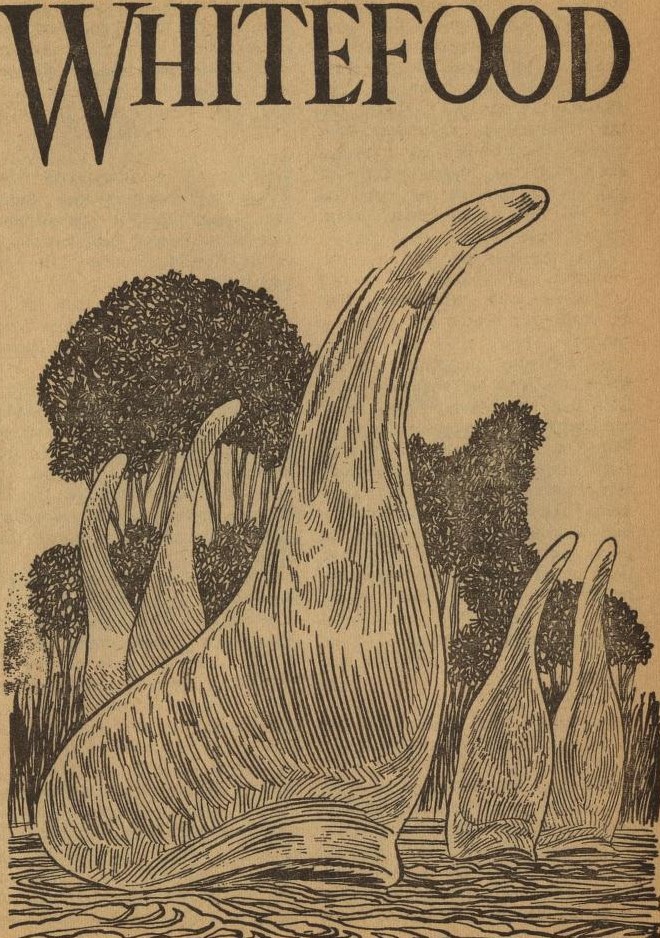

These are dinosaur-sized, single-celled animals the Thrint use for food, feeding them on yeast. There turns out to be much more to them than meets the eye.

Racing animals, like horses or greyhounds on Earth.

The interiors of these trees act as rocket fuel.

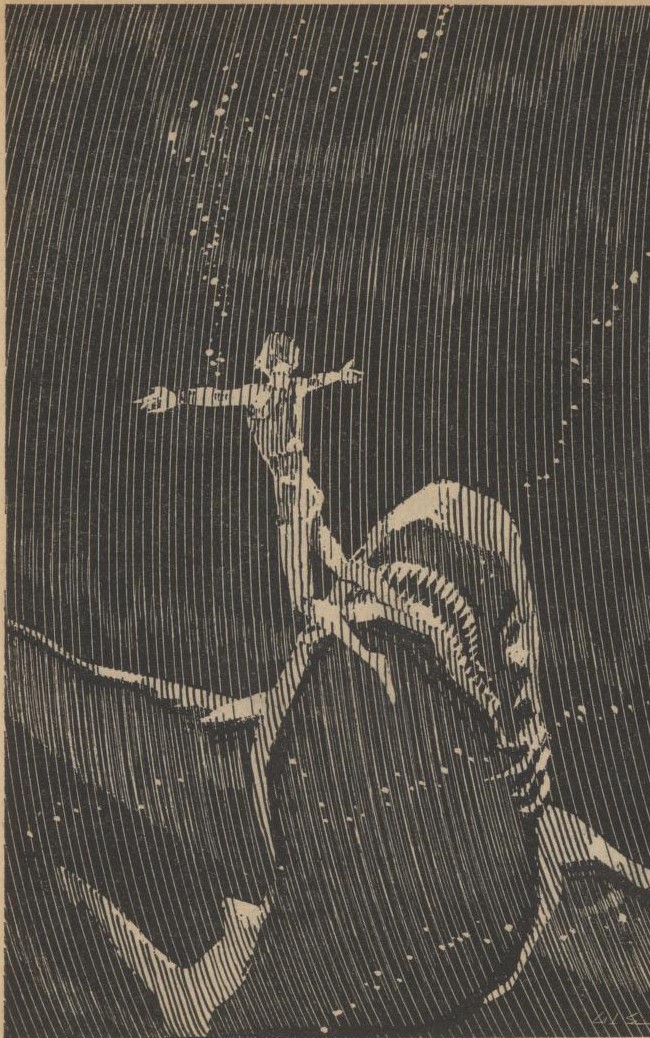

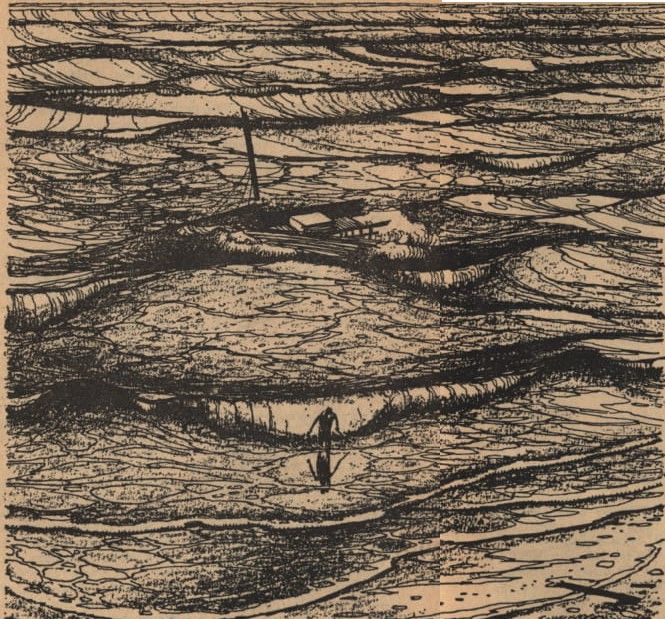

At the same time, the real Kzanol escapes from his stasis suit. This leads to a wild chase across the solar system, as both Kzanol and Larry/Kzanol race to find the other stasis suit, which contains a telepathy-enhancing device that would allow the wearer to control all the minds on Earth. Both Earth-dwellers and the colonists who inhabit the asteroid belt head out after the pair. There's an economic cold war going on between Earthers and Belters, adding to the tension.

Kzanol thinks the other suit is on Neptune, but it turns out to be on Pluto, which used to be a moon of Neptune a couple of billion years ago.

This is a fast-moving, complex story with a richly imagined background. The author clearly did a lot of work creating his fictional universe and populating it with a wide variety of organisms. There are so many concepts thrown out that some readers may feel overwhelmed. Certain elements are not fully explored. (The slave that Kzanol throws into his spare suit seems to have no relevance to the plot. And what's going to happen to the colonists on Jinx? Maybe a sequel?) Overall, however, it's a fine novella, indicative of an important new talent.

Four stars.

Undersea Weapons Tomorrow, by Joseph Wesley

The first of a pair of nonfiction articles in this issue imagines naval warfare two decades from now. The scenario is similar to the Cuban situation, heated up quite a bit. The Good Guys set up a blockade of an unfriendly island. The Bad Guys use submarines to attack Good Guy shipping. The author considers the balance of wins and losses in this aquatic battle. (For example, how many ships do you need to sink to make up for the number of submarines lost in the process?)

He also discusses locating the enemy via spy satellites, very slow seagoing bases for aircraft, and porpoises as allies. It's a rather dry piece, with some interesting aspects.

Two stars.

Scarfe's World, by Brian W. Aldiss

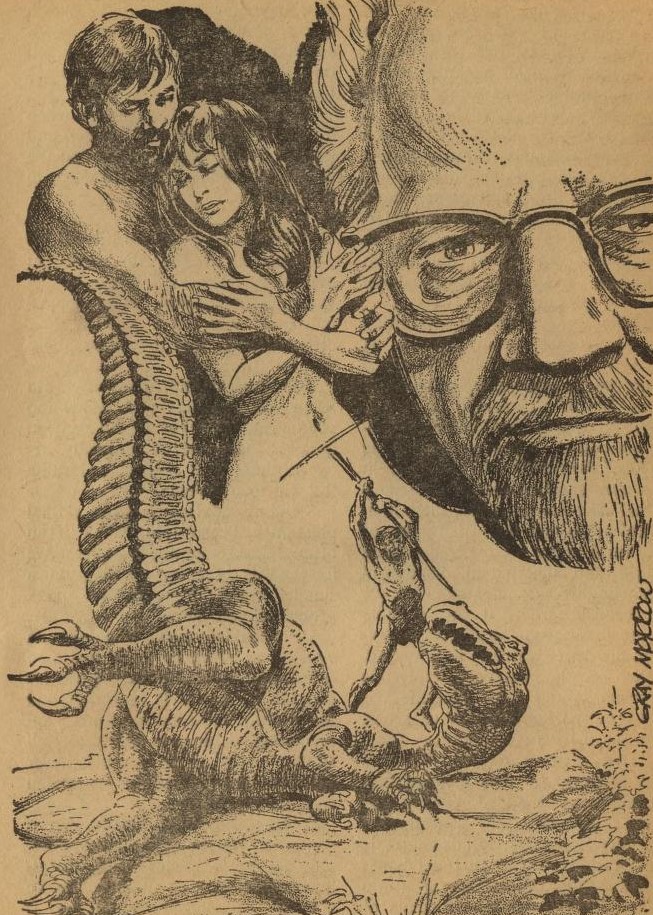

Illustration by Gray Morrow

This starts like one of those corny old movies where cave people and dinosaurs live at the same time. There are a couple of odd things about this primitive world, however. Sometimes people just dissolve, and the male protagonist doesn't really understand why he wants to be near the female protagonist.

We soon find out that the humans and dinosaurs are miniature forms of artificial life, created for study. The process sometimes breaks down, explaining the dissolving, and the organisms don't reproduce, explaining the caveman's confused feelings.

There really isn't much to this story other than its basic concept. The last third returns to the point of view of the caveman, which pretty much rehashes what went on in the first third.

Two stars.

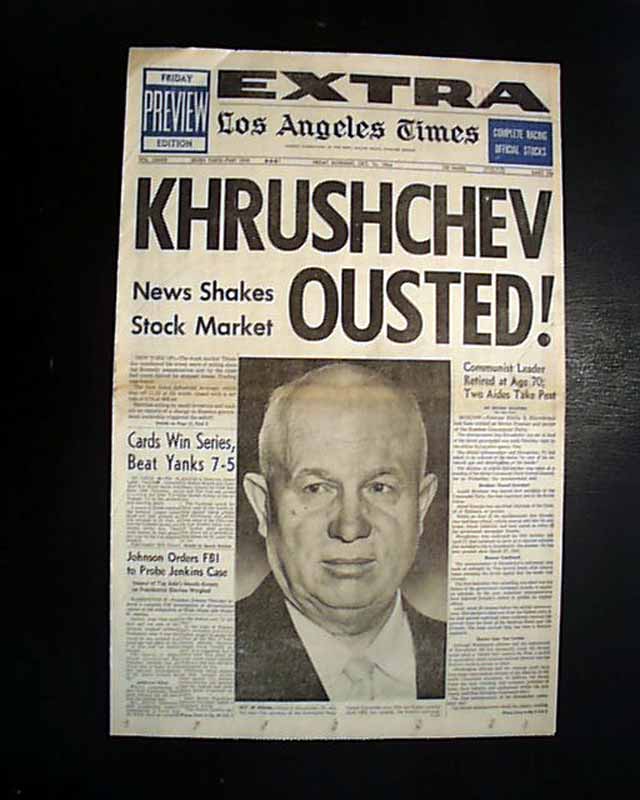

Phobos: Moon or Artifact?, by R. S. Richardson

Our second science article answers the question posed in its title right away. The author considers a Russian article from 1959 that suggested that Phobos is hollow, rejects it, and tells us why. The reasoning is highly technical. If I understand things correctly, when a moon is slowed in its orbit by something or other, it approaches the planet. Thus, although its velocity was decreased at first, it actually increases later.

Apparently Phobos increased its velocity due to this effect, but Deimos did not. One explanation for the observed effect would be if Phobos had an extremely low mass for its size; as if it were a hollow artificial satellite, for example. The author points out that there are several other explanations for the phenomenon, and that it really isn't that well established anyway. The whole thing will probably be of more interest to experts in orbital mechanics than the general reader.

Two stars.

By Way of Mars, by Ron Goulart

A guy falls for a girl, but she keeps standing him up at their dates. The Government Lovelorn Bureau tells him to forget her, but he doesn't give up that easily. Things rapidly get way out of hand, as the fellow gets in trouble with the cops, is shanghaied to Venus, escapes to Mars, and becomes the leader of a rebellion on the red planet.

I found the author's satiric portrait of a near future Earth, with suicide clubs and sex book plotters, more effective than the protagonist's interplanetary misadventures. The intent seems to be comic, although nothing particularly funny happens.

Two stars.

Pariah Planet, by Lloyd Biggle, Jr.

Illustrations by John Giunta

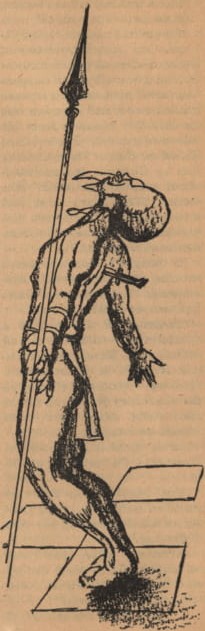

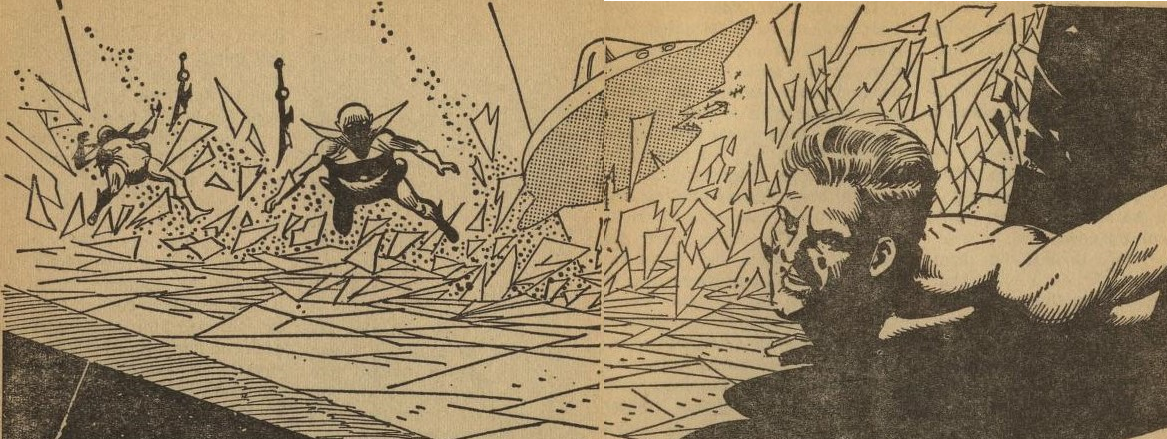

A spaceman kills a man in a bar fight on a planet with an odd system of justice. Although it was self-defense, he is convicted of murder, and transported to a prison planet. The underground society of this world is ordinary enough, with a couple of exceptions.

There are two groups of citizens. Type A people wear all different kinds of clothing, but Type B people must wear black at all times. Type B citizens are also required to repeat the crimes for which they were convicted, with the Type A citizens as victims. The protagonist, for example, is told to murder one Type A person each week.

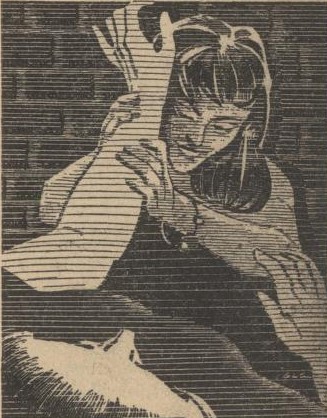

The Type A people aren't really bald, as shown here, but the illustration sort of clues the reader in on what's going on.

This leads to a crisis of conscience, as the unspecified consequences of failing to commit one's assigned crime are said to be very serious indeed. As time goes by, the main character grows more and more fearful of what fate awaits him, and finds himself tempted to kill one of the Type A people, who seem like perfect victims.

The protagonist in a brooding mood.

The contrived situation reminds me of the sort of thing that used to show up a lot in Galaxy in the old days, with some aspect of society reflected in a funhouse mirror. Here, of course, it's crime and punishment. You'll probably figure out the nature of the Type A people, and how this eccentric system of justice is supposed to work, long before the end.

Two stars.

That's About the Size of It

After a big start, the second half of the magazine shrinks into a collection of disappointing little stories and articles. Maybe it's just the contrast between Niven's wide-ranging imagination and much shorter, less ambitious pieces. In any case, the publication is large enough to accommodate losers as well as winners. What do you expect for half a buck, anyway?

A big coin for a big magazine.

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[January 14, 1965] The Big Picture (March 1965 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v02n06_1965-03_0000-2-672x372.jpg)

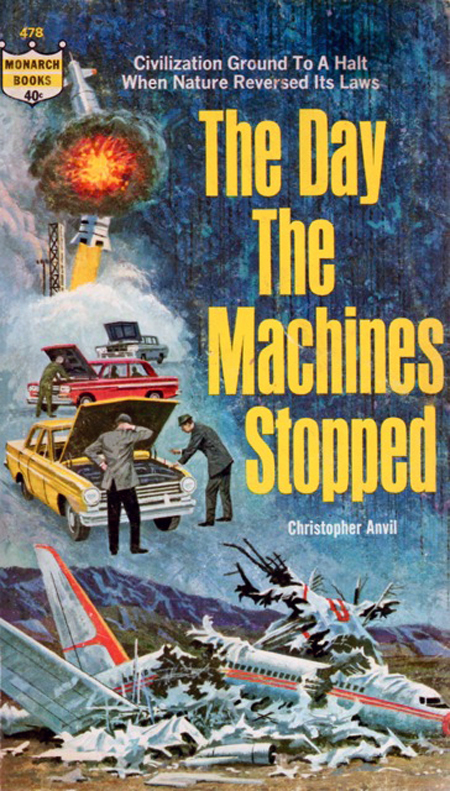

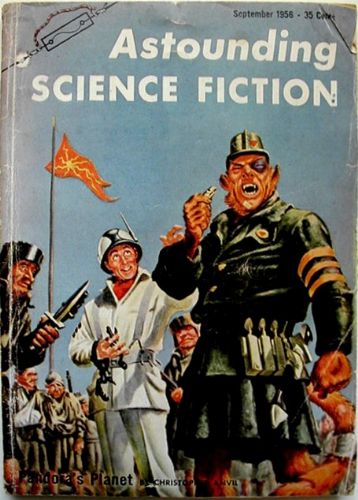

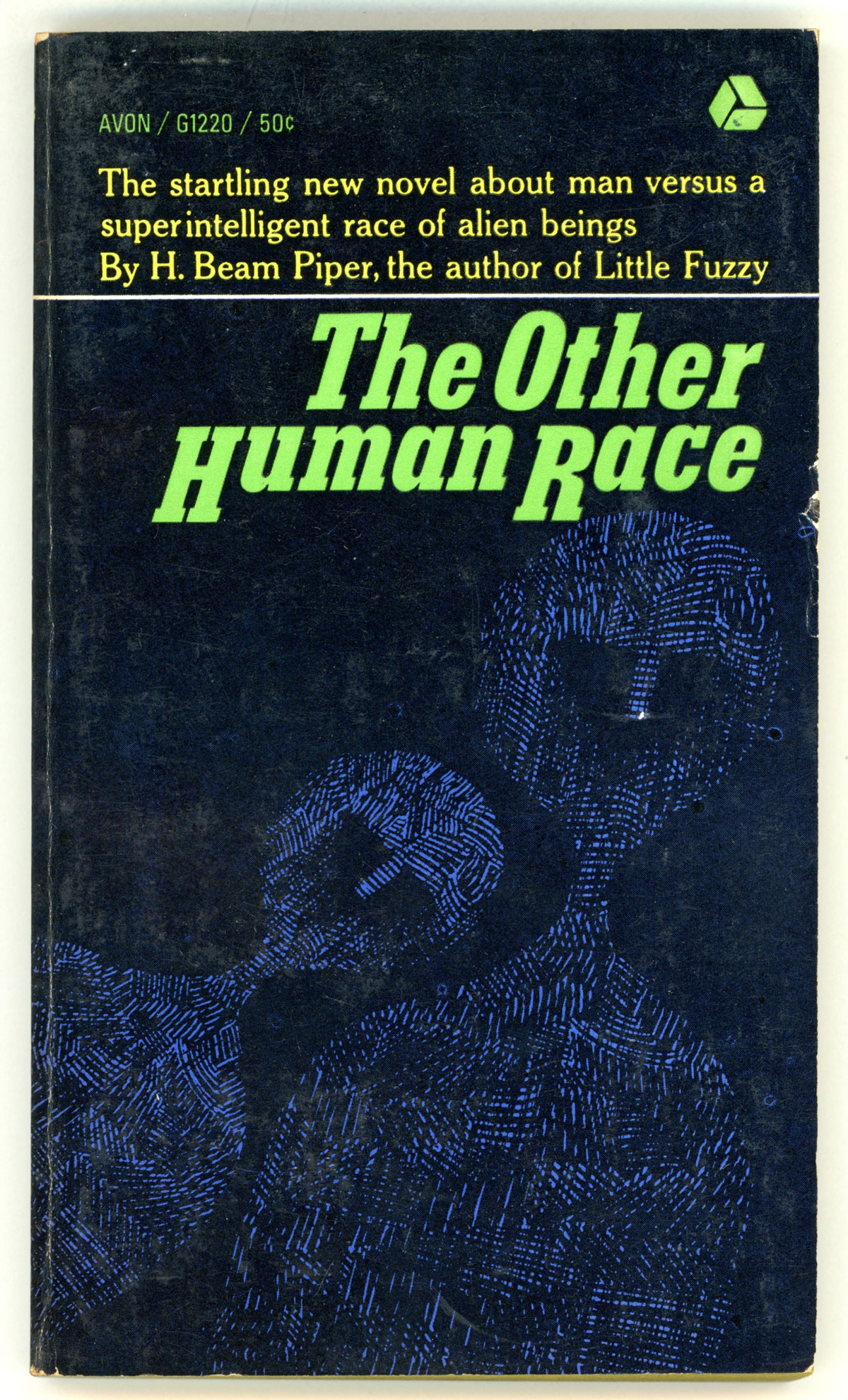

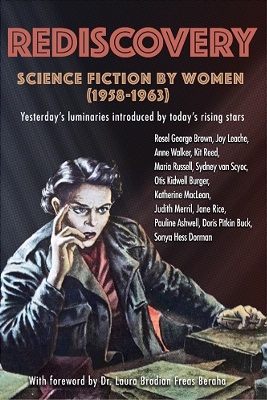

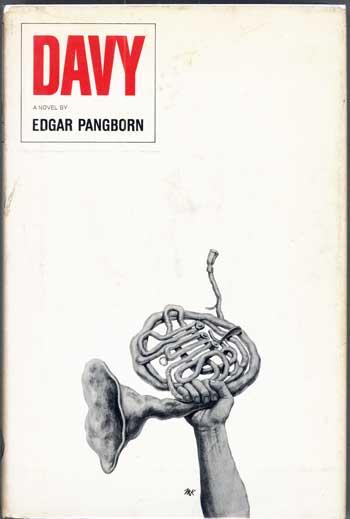

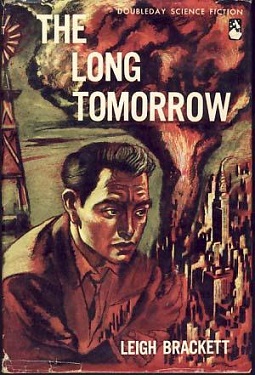

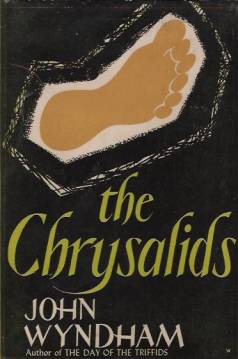

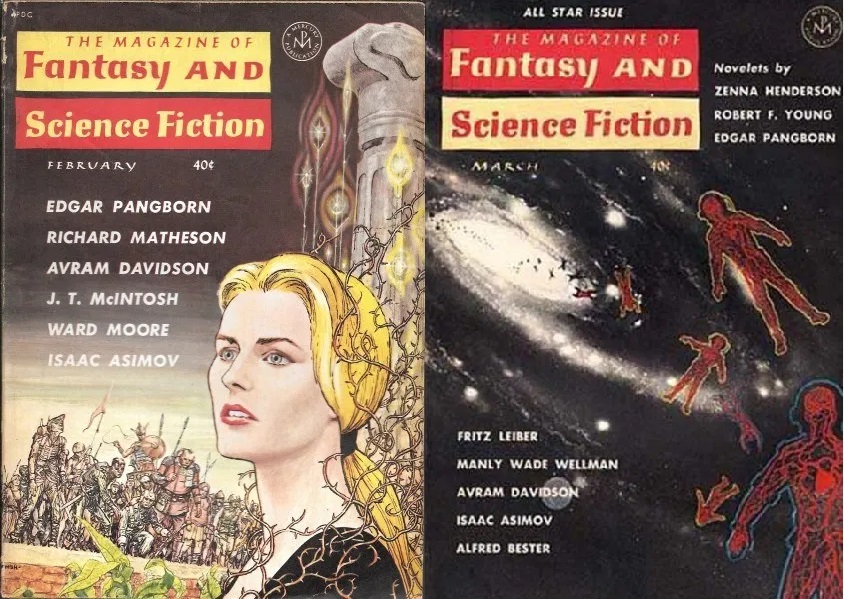

![[January 4, 1965] Madness: 2, Sanity: 1 (January Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/650104covers-672x372.jpg)

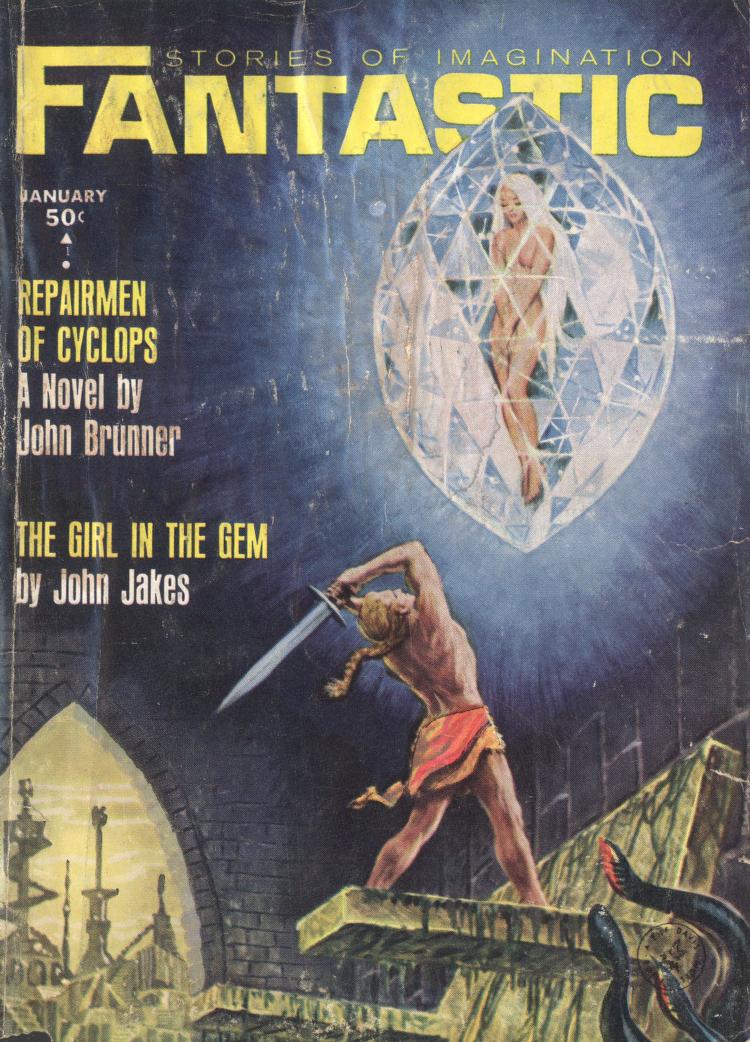

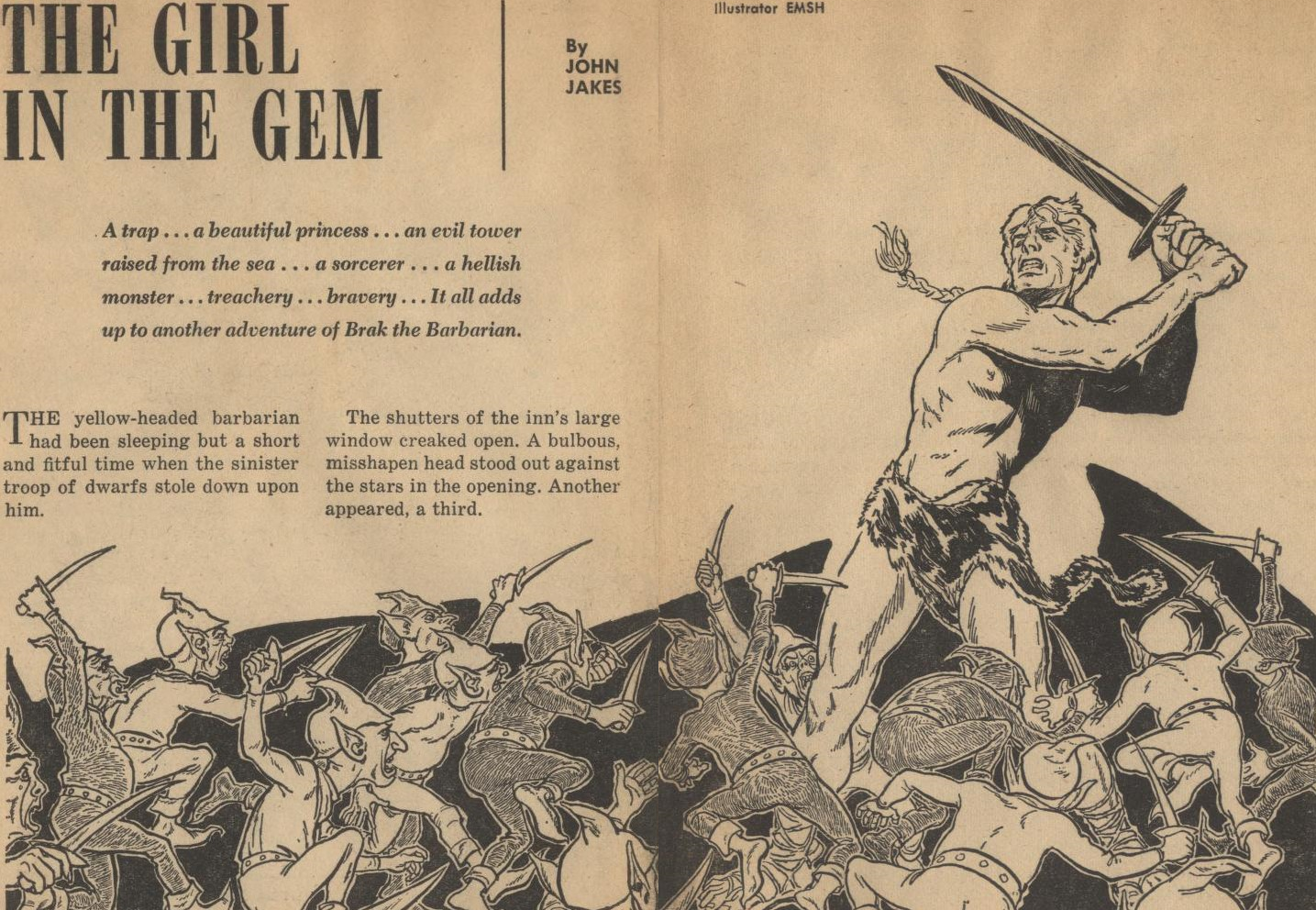

![[December 23, 1964] Odds and Ends (January 1965 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Fantastic_v14n01_1965-01_0000-2-672x372.jpg)

![[December 19, 1964] December Galactoscope #2](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/641219covers-672x372.jpg)

![[November 21, 1964] Bridging the Gap (December 1964 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Fantastic_v13n12_1964-12_0000-2-672x304.jpg)

![[October 24, 1964] Nothing Lasts Forever (November 1964 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Fantastic_v13n11_1964-11_0000-4-672x205.jpg)

![[October 18, 1964] Out in Space and Down to Earth (October's Galactoscope #1)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/641018covers-672x372.jpg)

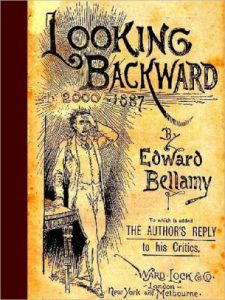

![[September 24, 1964] Looking Backward (October 1964 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/fantastic_196410-3-383x372.jpg)

![[September 16, 1964] The Waiting Game (November 1964 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/worlds_of_tomorrow_196411-3.jpg)

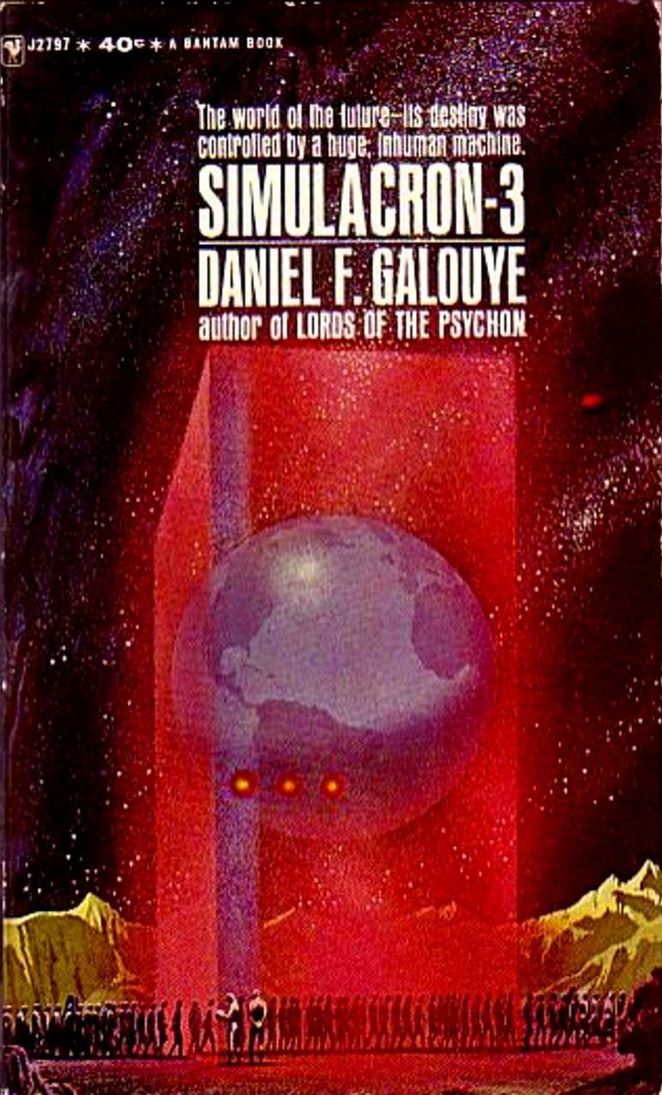

![[July 30, 1964] Are You For Real? (<i>Simulacron-3</i> AKA <i>Counterfeit World</i> by Daniel F. Galouye)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/330px-DanielFGalouye-Simulacron-3-330x372.jpg)