by Victoria Silverwolf

The Long, Hot Summer

There has been intense heat in many major cities in the eastern United States this month, particularly over the Independence Day weekend. On Sunday, July 3, New York City reached an all-time high for that date with a temperature of 107 degrees. Newark wasn't far behind, at 105 degrees, and Philadelphia was close, with 104.

And Long Island, too.

Cold, Cold Heart

As if editor Frederik Pohl wanted to help us forget about the blistering heat wave, the latest issue of Worlds of Tomorrow is centered around a topic that is literally chilling.

Cover art by Paul E. Wenzel.

Before we step into the freezer, however, let's take a look at the lead story, mistakenly called a Complete Short Novel on the title page, although even the magazine's table of contents admits that it's just a novelette.

Heavenly Host, by Emil Petaja

Illustrations by Jack Gaughan.

Our hero's name is Kirk. If what I read in the trade papers is correct, that is also the name of the main character in the upcoming science fiction television series Star Trek. I assume that's just a coincidence. I guess Kirk is a good, manly name.

Anyway, this Kirk serves aboard a spaceship. He's a bit of a rebel, and winds up punching the tyrannical captain of the vessel. He's thrown into the brig, but manages to escape in a sort of lifeboat. (The implication is that the captain and the ship's cook kind of encouraged him to get away.)

This seems to be a case of jumping out of the frying pan and landing in the fire. (Pardon the corny metaphor. The heat must be getting to me.) Kirk winds up on a planet that is covered with a tangle of stinky vines. He manages to survive by eating the smelly plant and drinking rainwater, but life is hardly pleasant. There are holes here and there in the vines, so Kirk goes down to take a look around.

Exploring the world below.

After narrowly escaping being devoured by a giant worm, Kirk discovers that there's a wondrous Utopia under the odoriferous flora. He meets a beautiful woman, dancing gracefully, who quickly starts smooching on him and takes him on a boat ride.

A self-propelled gondola is the best way to travel in style.

At this point, the reader figures that the woman is just a figment of Kirk's imagination. Her name is Sombra, Spanish for shadow, which seems at first to be another hint that she's a phantom. Besides that, we already know that Kirk has imaginary conversations with his wise Mexican grandfather. However, she and the lovely community wherein she dwells turn out to be quite real.

Is this the Emerald City of Oz?

It seems that a bunch of colonists landed on the planet long ago, and managed to create a society without want, the population devoting all its time to artistic endeavors. This seemingly impossible task, they say, was done with the help of a benign deity called Hur. Kirk and Sombra are in love, of course, and he's eager to marry her, but things change when he gets his first look at the god responsible for this paradise.

Kirk meets Hur.

This is a strange story. It starts off as a tale of survival, becomes something of a wish-fulfillment fantasy, adds a touch of horror, and ends in an ambiguous fashion. I wouldn't call it boring, but I never believed anything that was happening. (One major quibble occurs to me: the people in the utopian city claim that they depend on folks like Kirk showing up to avoid inbreeding. Am I supposed to believe that people randomly land on this seemingly worthless planet frequently?)

Two stars.

Immortality Through Freezing, by Long John Nebel, et al.

This is actually an abridged transcript of a panel discussion broadcast on a New York City radio station. The topic is the possibility of freezing people at the moment of death and reviving them in the future, when medical technology will be able to cure their ailments and bring them back to life.

Besides the host, radio personality Long John Nebel, the group included Frederik Pohl, editor of this very magazine; R. C. W. Ettinger, who wrote a book on the subject, an excerpt from which appeared in the second issue of Worlds of Tomorrow; Joseph Lo Presti, an ophthalmologist; Shirley Herz, a public relations consultant; and the famous pianist/comedian Victor Borge.

That's an oddly mixed group of folks, and I wonder if they just happened to grab whoever was hanging around the radio station at the time. In any case, the guests discuss the definition of death and whether extreme cold could keep people in a state of suspended animation. This is nothing new to science fiction fans, and it pretty much just rehashes the previous article I mentioned. At least the subject matter might help you feel a little cooler and beat the heat.

Two stars.

Deliver the Man!, by Ray E. Banks

Illustrations by Norman Nodel

A starship is on its way to a conference of various alien civilizations. It seems that Earth is considered as something of a backwater, worthy only of being conquered. The ambassador aboard the vessel must reach the meeting on time and manage to convince the extraterrestrials otherwise.

Complicating matters is the fact that Martian colonists, now the enemies of Earth, attack the ship while it's on its way. A space battle follows.

A female warrior in a dogfight in space.

Our hero comes to the rescue of an inexperienced pilot, saving her bacon when she faces two opponents at once. She is hurt but survives the skirmish, only to face further challenges aboard the vessel.

Injured in battle.

There's a planet that insists the ship wait around while they celebrate an anniversary, so that the ambassador will be much too late to save Earth from destruction. The captain stays behind, allowing the vessel to sneak away, although he knows this will mean his death when the deception is discovered. An unpleasant fellow takes command, leading to a love triangle that ends in tragedy.

A crime of passion.

As if that weren't enough trouble, there's the possibility that an alien spy, disguised as a human being, is aboard the ship, intending to sabotage the mission. More deaths follow.

Another murder aboard ship.

All seems hopeless by the end, until our hero steps up and does what has to be done. The conclusion involves the ship's navigator, an eccentric woman who also serves as the hero's love interest.

The enigmatic navigator.

There's certainly enough action going on to satisfy readers looking for slam-bang adventure. The hero has so many obstacles in his way that it almost becomes ludicrous. You also have to assume that starship officers are going to act in completely irrational ways out of sexual jealousy.

Although partly depicted as objects of lust, it was nice to see women aboard the ship in important positions. The navigator, in particular, is an interesting character, although you'll probably figure out what role she plays in the plot.

Two stars.

The Most Delicious Foe, by Lawrence S. Todd

Illustrations by the author.

Our hero runs a business that will perform just about any service for the right fee. (I was reminded of Robert A. Heinlein's 1941 story "–We Also Walk Dogs". Proofreader, please note that the dash and quotation marks are part of the story's title.)

His latest job is to stop a war between two alien species. Each one wants to eat the other. The reptilian aliens just think the centipede-like aliens are tasty, while the centipede-like aliens savor the experience of imagining the lives of the reptiles while devouring them.

Two reptilian aliens read the news. Yes, the text states that they wear tam-o'-shanters.

Our hero has to figure out a way to please the appetites of both species in order to prevent wholesale slaughter.

Who is having whom for dinner?

As you can tell, this is a silly story, apparently intended as a comedy, although nothing particularly funny happens. The author is much better known as a cartoonist and illustrator, and he might want to stick to that line of work in the future.

Two stars.

Tom Swift and the Syndicate, by Sam Moskowitz

The indefatigable historian of all things related to science fiction delves into the subject of children's adventure books of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As the title suggests, the main focus is on the countless stories of Tom Swift and his amazing inventions. However, the article also includes many other endless series, such as Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys. The bulk of these were plotted by a single man and actually written by a bunch of authors under house names. The Tom Swift, Jr., series continues to this day.

As usual, the author possesses an absolutely astounding amount of information about the subject. Also as usual, the resulting essay is less than compelling.

Two stars.

Homogenized Planet, by Allen Danzif

Illustrations by Dan Adkins.

One of the members of an exploration team on Mars goes off for several days, much longer than he could possibly survive with his limited air supply. Incredibly, he comes back just fine. In fact, he can survive in the extremely thin Martian atmosphere without any problems.

The other folks sedate him and strap him down during the voyage back to Earth. I guess they don't want to take the chance that he's really a Martian shapeshifter or something. Despite their precautions, things start to go wrong. People change from one person into another, or disappear entirely.

An eerie transformation.

At this point, you might think of John W. Campbell, Jr.'s 1938 novella Who Goes There?, with its shapeshifting alien. (Not so much the 1951 movie The Thing from Another World, which eliminated the shapeshifting. On the other hand, I was reminded of the 1958 film It! The Terror from Beyond Space.)

However, things turn out quite differently than expected, and the mood changes drastically. When we finally find out what's really going on, the premise is of some interest, but it requires pages and pages of exposition. The story really grinds down to a halt during its last section.

Two stars.

Island of Light, by Lawrence A. Perkins

Illustrations by Arkin. I have not been able to discover the artist's last name. Could it possibly be Alan Arkin, the star of this year's hit comedy The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming? He's had a couple of stories published in Galaxy.

In the near future, a city in the northwestern part of the United States takes drastic measures against crime. There is only one way to get into the place, which has expanded so greatly that it takes up part of three states. The normal activities of everyone in the city are recorded, so that computers can predict their whereabouts at any particular time with reasonable accuracy. There are many other methods used to ensure that it is nearly impossible to get away with a crime.

Citizens of Utopia?

A detective from outside the city arrives to observe the local crimefighters. A woman is beaten and robbed, left alive but in a coma. The investigation demonstrates the city's unusual methods, and reveals something about the visiting detective.

The premise is an interesting and provocative one, raising many questions about the proper way to balance freedom and security. Frankly, this story came as something of a relief after all those outer space adventures. The biggest flaw is that it's full of long expository speeches, as the local detective explains things to his guest.

Three stars.

We're Havin' a Heat Wave

Well, that was a disappointing issue, not doing much to take my mind off the hot weather. Perhaps the best way to use it would be to flap the pages against your face to cool down. Either that, or read it while sitting in a room made nice and comfortable by modern technology.

You don't really need to wear a snowsuit while running an air conditioner.

Tune in to KGJ, our radio station, for the coolest and the hottest hits!

![[July 18, 1966] Arrivals and Departures (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The War Machines)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/660718trapthemachine-672x372.jpg)

![[July 14, 1966] October's Judgment (July Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/660714coversjpg-672x372.jpg)

![[July 12, 1966] Cool It! (August 1966 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v04n01_1966-08_0000-2-672x330.jpg)

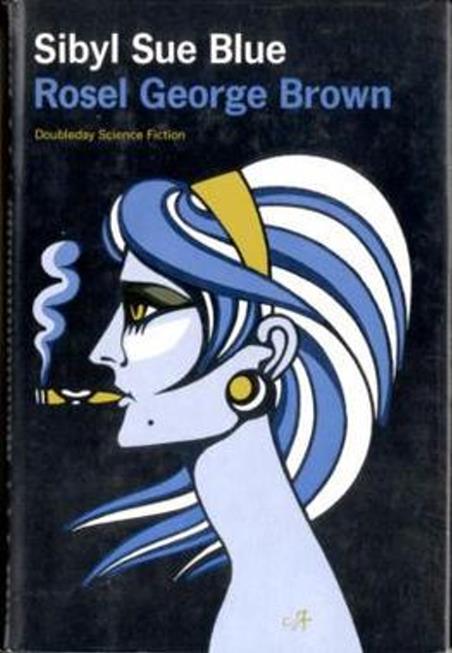

![[July 10, 1966] Froth, Fun, and Serious Social Commentary (<i>Sibyl Sue Blue</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Sibyl_Sue_1966-452x372.jpg)

![[July 8, 1966] South Pohl (August 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/660708cover-672x372.jpg)

![[June 30, 1966] Not Reading You (July 1966 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/660630analog-500x372.jpg)

![[June 24, 1966] Increments: <i>World's Best Science Fiction: 1966</i>, edited by Donald A. Wollheim and Terry Carr](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/wollheim-66-cover-449x372.png)

![[June 20, 1966] First Impressions Can Be Misleading (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Savages)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/660620underarrest-672x372.jpg)

![[June 16, 1966] Calm Spots (July 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/660616cover-672x372.jpg)

![[June 12, 1966] Which Way to Outer Space? (New Writings In SF 8)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/New-Writings-in-SF8-Cover-259x372.jpg)