by Victoria Silverwolf

Happy New Year!

We have to be told twice that it's the Fabulous Flamingo.

Here we go with my first magazine review of 1967. I'm glad to say that the year begins with a bang, as the lead novella in the latest issue of Worlds of Tomorrow is a knockout. Will the rest of the stories and articles be anywhere near as good? Let's find out.

Cover art by Gray Morrow.

The Star-Pit, by Samuel R. Delany

Delany has already published several novels, but I believe this is his first appearance in a science fiction magazine. It's certainly an auspicious debut. That's not such a big surprise, as his book Babel-17 won high praise from my esteemed colleague Cora Buhlert, and was the overwhelming choice for the most recent Galactic Stars award for Best Novel.

Illustrations by Jack Gaughan.

The narrator begins with an account of an incident in his past that puts him in a bad light. While living on a planet with two suns, as part of a group marriage, he destroyed a miniature ecological system built by the family's children, as shown above. (I pictured the thing, which is something like a super-sophisticated ant farm, as quite a bit larger.)

Two of the alien organisms released during the narrator's destruction of the object. I pictured them as much smaller.

Several years later, the narrator is at the edge of the galaxy, working as a mechanic for starships. For a while, it seems as if the opening section of the story has little to do with the rest, but it all ties up at the end.

This is a future time when travel throughout the Milky Way is possible, but not beyond its borders. Attempting to do so results in insanity and death for the unfortunate extragalactic voyager. That is, unless you happen to be one of the rare people known as golden. (The word is used as a noun here, and serves as both the singular and plural form. Delany displays his interest in language in this story just as he did in the novel mentioned above.)

Golden have both hormonal and psychological abnormalities that allow them to travel to other galaxies, bringing back rare and valuable items. They are also mean or stupid, as one character says, prone to foolish actions and sudden violence. As you'd expect, ordinary people resent them, not only for their unpleasant personalities, but out of jealousy for their ability to escape the Milky Way.

The narrator and a young man encounter an unconscious golden. (It seems that a disease brought back from another galaxy causes intermittent blackouts.)

Carrying a golden.

They bring the golden to a woman who is a projective telepath. Let me explain. That means that she causes other people to experience her sensations. She was also born addicted to a hallucinatory drug taken by her mother. Combined with her telepathic ability, the drug allowed her to serve as a psychiatric therapist, helping golden overcome psychic shock caused by their journeys.

The projective telepath. She may be the most fascinating character in the story.

Another incident involving two golden leaves the narrator with a starship designed to travel to other galaxies. The question of what should be done with it leads to multiple complications, both tragic and hopeful. (I haven't even mentioned the narrator's assistant, who plays a major part.)

There's also a dramatic scene involving waldoes.

I have only given you a small taste of a very intricate story. Despite having the depth and complexity of a full-length novel, it is never confusing. The richly imagined future reminds me a bit of Cordwainer Smith, although Delany's narrative style is much more intimate than Smith's mythologizing.

The writing is beautiful, and the author creates living, breathing characters. The plot deals with love, hate, marriage, parenthood, and much more. It will break your heart and bring you much joy.

Five stars.

The Psychiatric Syndrome in Science Fiction, by Sam Moskowitz

The indefatigable historian of fantastic fiction offers a look at the use of psychology in the genre. He traces this theme back to Robert Louis Stevenson's famous novella Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, then talks about a lot of other stories.

A big chunk of the article deals with the works of David H. Keller, a practicing psychiatrist. I'm not convinced that all the Kelleryarns discussed here are really relevant to the topic.

There's also discussion of The Jet Propelled Couch, a chapter from the book The Fifty-Minute Hour by psychologist Robert M. Lindner. (He also wrote the book Rebel Without a Cause, which gave its title, if nothing else, to the famous movie of the same name.) This is the true account of one of Linder's patients, who became obsessed with a fantasy world in which he was the hero of outer space adventures. Although quite interesting, the case has little to do with the subject of psychiatry in science fiction.

The article wanders all over the place, and it is not very well organized. It's not as dull as some of the author's endless listings of old stories, but it's not his best work, either.

Two stars.

The Planet Wreckers, by Keith Laumer

Illustrations by Gray Morrow.

Our hapless hero is in a crummy hotel room, trying to get some sleep, when he hears noises coming from above. Since he's in a Laumer story, he doesn't just call the front desk. He climbs up the fire escape to see what's going on. What seems at first to be a lovely young woman turns out to be a weird alien being.

She's some kind of outer space law enforcement agent. It seems that other weird aliens plan to cause a series of disasters on Earth, in order to record them as a form of entertainment. (Think of Hollywood spectaculars.) She doesn't care about the fact that huge numbers of human beings will be killed; she just wants to protect the environment.

The alien policewoman and our pajama-clad protagonist go zooming all over the place in her flying machine, trying to stop the catastrophes. It all winds up with the hero inside the alien studio, so to speak, and with another revelation about his female companion.

Can you tell this isn't the most serious story in the world?

Laumer writes a lot of comic adventures, along with serious ones, but I think this may be the silliest yet. There doesn't seem to be any real satire here, although I guess you can interpret it as a dig at the movie industry. It's full of goofy-looking aliens with wacky names, and plenty of slapstick mishaps. If you're looking for a brainless farce, go no further.

Two stars.

Sun Grazers, by Robert S. Richardson

Inspired by the appearance of the comet Ikeya-Seki, which was visible from late 1965 to early 1966, the author discusses comets that pass close to the sun. He also talks about how comet groups form (larger comets breaking up into smaller ones) and whether the paths of comets suggest a tenth planet beyond Pluto (inconclusive.) The article ends with the author's own struggle to view Ikeya-Seki, and how he made a rough guess as to the size of its tail.

The author describes Ikeya-Seki as a disappointment. (The name comes from two Japanese comet hunters who discovered it independently, by the way.) Other accounts of which I am aware state that it was very bright, visible in the daytime. The article is moderately informative, but a little on the dry side. Like the author's experience with the comet, it isn't as spectacular as one might wish.

Two stars.

Station HR972, by Kenneth Bulmer

The superhighways of the future, where vehicles travel two hundred miles per hour and more, require teams of specialists to deal with accidents. This includes transplanting limbs and internal organs. All in a day's work.

There's not really much plot here. It's kind of a slice-of-life story, detailing the activities of the folks who have to deal with the gruesome effects of high speed collisions. I'm reminded of Rick Raphael's story Code Three, which had a very similar theme. Frankly, that one was a lot better.

Two stars.

About 2001, by David A. Kyle

No, this isn't an article about the first year of the next millennium. It's a very brief piece concerning the upcoming movie 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Director Stanley Kubrick (with beard) and writer Arthur C. Clarke (without hair.)

There's not a lot of information here, as the creators are keeping things hush-hush. What we do find out is intriguing. Will the finished product live up to Clarke's prediction that It'll be the greatest science fiction picture ever made? Only time will tell.

I can't really blame the author of this article for frustrating my desire to learn more about the film, as he was obviously prevented from finding out too much. That doesn't keep me from wishing it were a lot longer.

Two stars.

The Shape of Shapes to Come, by Robert Bartlett Riley

An architect imagines what buildings and cities might be like in the future. This involves three areas of prediction. From easiest to most difficult, these are technological changes; what people will choose to do with these techniques; and how this will change society.

Topics discussed include advanced building materials, new forms of lighting, and greater control of interior environments. The author laments the lack of mass-produced housing, similar to the way automobiles are manufactured, which would greatly reduce the price of a home. In the most imaginative section, he dreams of shelters made from force fields rather than physical materials, and of personal Life Packs that would supply one with all the functions of a house.

I found this slightly interesting, but rather vague in its predictions and not very exciting. Despite the discussion of a couple of wild possibilities, the author seems to think that architecture is going to remain conservative for quite some time, avoiding the futuristic visions of science fiction writers.

Two stars.

The Fifth Columbiad, by Richard C. Meredith

Illustrations by Hector Castellon.

Many centuries before the story begins, aliens destroyed all humans on Earth. In what must have been the most embarrassing mistake of all time, they thought the humans were other beings who were their deadly enemies.

The only people to survive were those who happened to be on starships at the time. Now, their descendants make war on the aliens, capturing their starships to add to the human fleets.

The plot involves the captain and crew of one starship. The vessel is badly damaged in battle, just barely managing to escape. The commander and a team of volunteers remain on the derelict vessel, hoping to lure an alien starship into docking with it so they can sneak aboard the enemy vessel and seize it for themselves.

Carnage on the starship.

This yarn reminds me of war stories in which a small team of commandos attacks an enemy installation against overwhelming odds. The Guns of Navarone in space, if you will. You know that some of the volunteers will be killed in action, but that the mission will succeed. I thought there might be some kind of ironic ending, given the mistake that started the war in the first place, but nothing like that happens.

There's some odd, smirking sexual content in this story. At the risk of sounding like a prude, I didn't think it was necessary to point out that the pseudo-reptilian aliens, who have a matriarchal society, have breasts like human women.

Not shown here, for reasons of good taste, I assume.

There's one volunteer who's only there so he can be a hero, thus earning the sexual favors of admiring women. The author tells us the female crew members wear nothing but skirts — no shirts or blouses, apparently — and gives us a fair amount of detail about the heroine's panties. (The excuse is that the interior of the alien ship is hot and humid, so the humans have to strip down to the basics.)

Two stars.

Coming To A Bad End

This issue really went into a nosedive after soaring to the heights of imaginative literature with Delany's novella. Scuttlebutt has it that Worlds of Tomorrow is on its last legs. That's too bad, as the magazine gave readers some very good stuff, along with a lot of not-so-good stuff. Very much a curate's egg, I'm afraid.

Cartoon by Wilkerson, from the May 22, 1895 issue of Judy.

A better known cartoon by George du Maurier, from the November 9, 1895 issue of the better known magazine Punch. Too similar to be a coincidence, I'd say.

![[January 16, 1967] Off to a Good Start (February 1967 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v04n03_1967-02_0000-2-672x372.jpg)

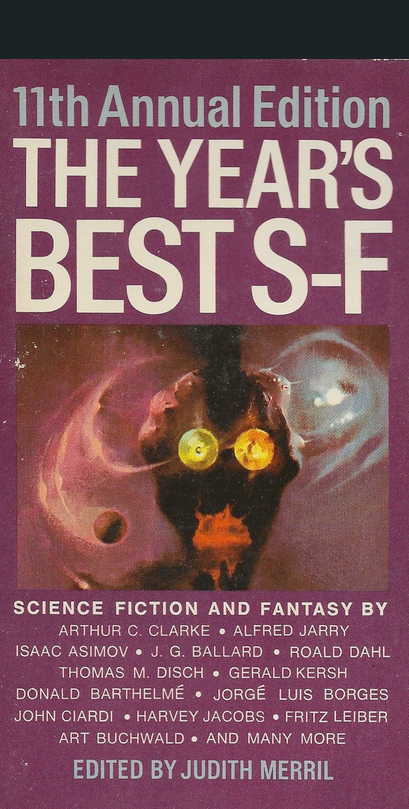

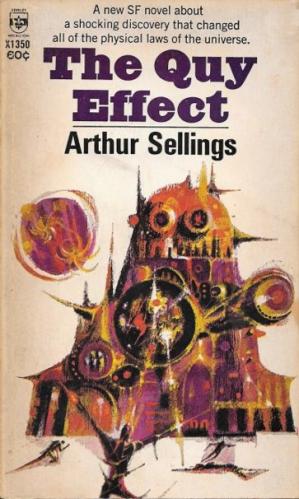

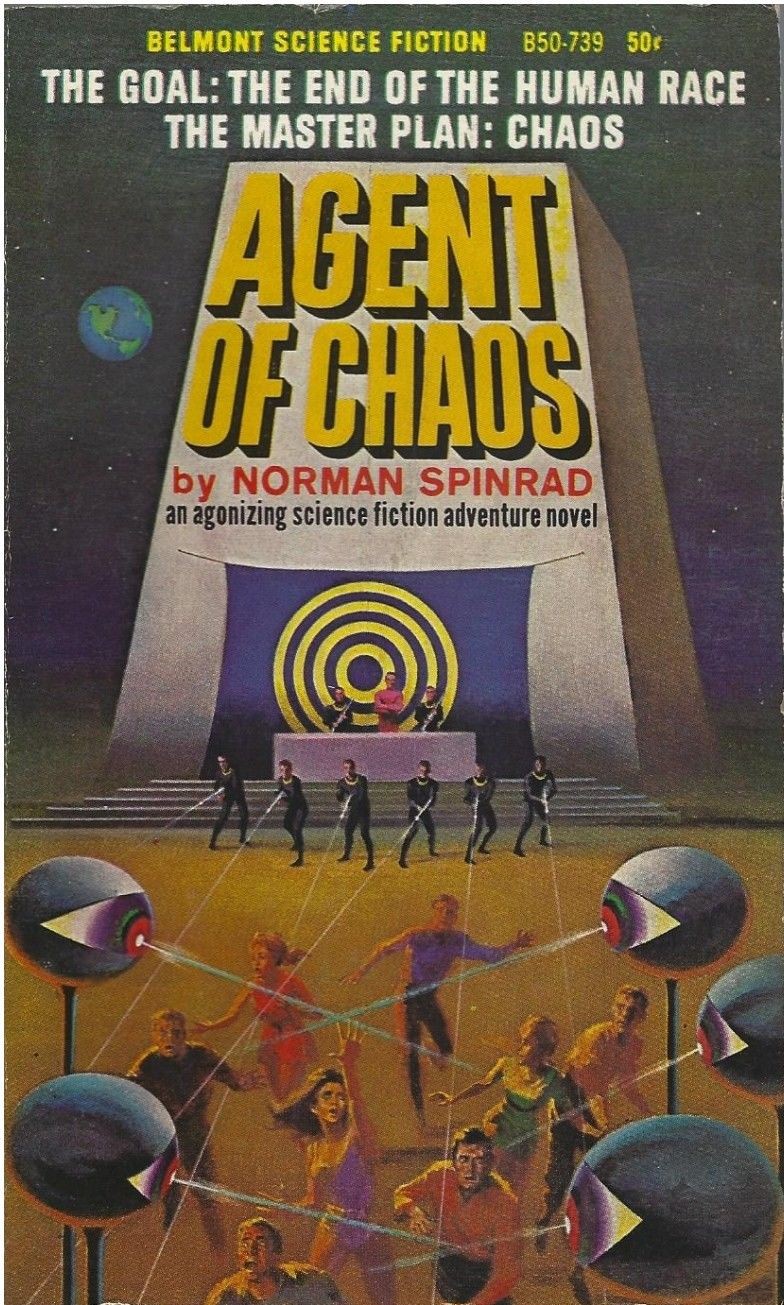

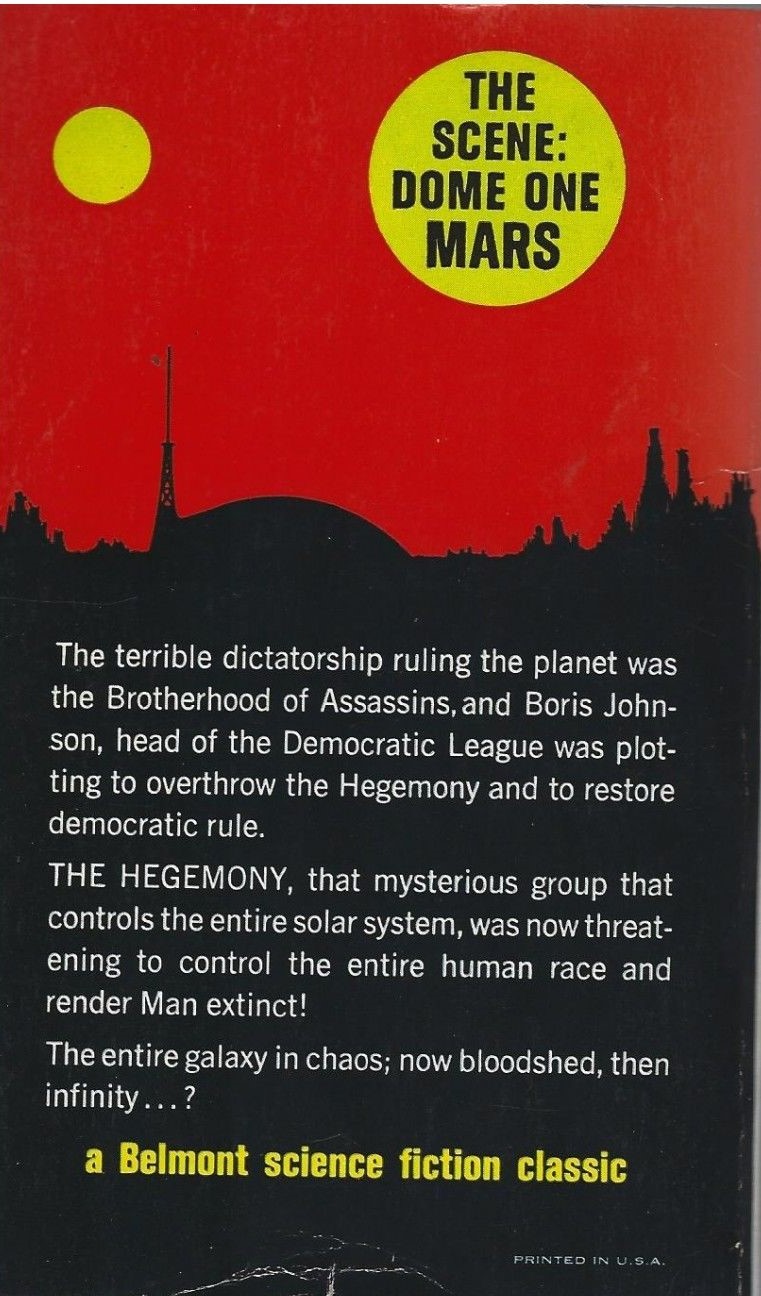

![[January 14, 1967] First batch (January Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/670114covers-672x372.jpg)

![[January 12, 1967] Most illogical (<i>Star Trek</i>: "The Galileo Seven")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/670112title-672x372.jpg)

![[January 10, 1967] Return to sender (February 1967 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/670110cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 8, 1967] So-So Historical, Delightful Doctor (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Highlanders)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/660108nicehat-672x372.jpg)

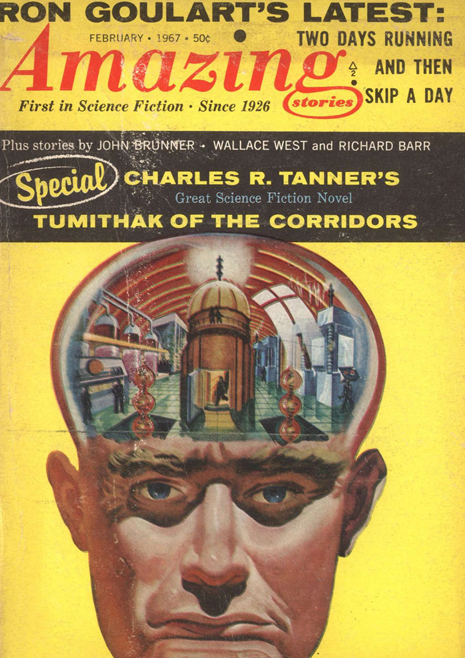

![[January 6, 1967] Happy Anniversary (February 1967 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/amz-0267-cover-465x372.png)

![[January 4, 1967] Six Impossible Things Before Breakfast (<i>Star Trek</i>: Shore Leave)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/670104title-672x372.jpg)

![[December 31, 1966] Barriers to quality (January 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661231cover-672x372.jpg)

![[December 26, 1966] Harvesting the Starfields (1966's Galactic Stars!)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661226plough-672x372.jpg)

![[December 24, 1966] Unquiet on the Romulan Front (<i>Star Trek</i>: "Balance of Terror")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661224title-672x372.jpg)