by Cora Buhlert

Protests in Poland

Student protests have been erupting all over Europe and even the otherwise nigh impenetrable iron curtain cannot stop them.

The latest country to be rocked by student protests is Poland. The protests were triggered when a production of the play Dziady (Forefathers' Eve) by Adam Mickiewicz, Poland's most celebrated poet, was pulled from the Warsaw National Theatre because of alleged anti-Soviet tendencies. In response, students protested against the cancellation of the play and censorship in general. More than thirty students were arrested during the initial protests in Warsaw and two of them were expelled from the University of Warsaw. The fact that both expelled students happened to be Jewish suggests that Anti-Semitism, which has been rearing its ugly head in Poland again in recent years under the guise of Anti-Zionism, may have played a role.

The Polish students, however, were not willing to give up and announced another protest for March 8. The authorities responded with violence and pre-emptively arrested several student leaders. Nonetheless, the protests spread to other Polish cities.

Buddha is a Spaceman: Lord of Light by Roger Zelazny

Roger Zelazny, of Polish origin himself, is one of the most exciting young authors in our genre and has already won two Nebulas and one Hugo Award, which is remarkable, considering he has only been writing professionally for not quite six years.

My own response to Zelazny's works has been mixed. I enjoyed some of them very much (the Dilvish the Damned stories from Fantastic or last year's novella "Damnation Alley" from Galaxy) and could not connect to others at all (the highly lauded "A Rose for Ecclesiastes"). So I opened Zelazny's latest novel Lord of Light with trepidation, for what would I find within, the Zelazny who wrote the Dilvish the Damned stories or the one who wrote "A Rose for Ecclesiastes"?

The answer is "a little bit of both" and "neither". Lord of Light is not so much a novel, but a series of interconnected stories, two of which, "Dawn" and "Death and the Executioner", appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction last year. To make things even more disjointed, the stories are not arranged in chronological order either.

The novel starts with the resurrection of Mahasamatman, Sam to his friends, who may or may not be a god. Sam is not happy about his resurrection, because he was pulled back into bodily existence from a blissful, Nirvana-like bodyless existence that was supposed to be a punishment, the only way of executing one who is functionally immortal. We gradually learn what brought Sam to this place, namely his rebellion against the gods of his world who keep the population downtrodden and oppressed .

Initially, Lord of Light appears to be a fantasy novel, but we eventually realise that the novel is set on a distant planet in the far future and that the gods and demigods we meet are the crew of the Earth spaceship Star of India, which landed here eons ago, while the demons are the original inhabitants of the planet. The human crew mutated themselves to better survive and reincarnate themselves in new bodies via mind transfer to become immortal. They rule over their descendants with an iron hand as self-styled gods. Sam, however, will have none of this and launches a rebellion.

Fantasy and science fiction have been drawing from European religion, mythology and history for decades. In Lord of Light, however, Zelazny draws on Hindu and Buddhist religion and mythology. The spaceship crew turned gods are based on Hindu deities, while Sam is based on Siddhartha Gautama a.k.a. Buddha.

Indian culture is popular right now and Indian influences can be seen in fashion, interior design, music (the Beatles have just embarked on a meditation sojourn in India) as well as in the yoga studios springing up in the big cities. Therefore, it was only a matter of time before Indian influences would appear in science fiction. Especially since it would be silly to assume that only white Christian westerners get to travel to the stars. There is a Christian character in Lord of Light, by the way; the ship's former chaplain Renfrew embarks on a crusade against the self-styled Hindu gods and their worshippers.

It is a refreshing change to read a science fiction novel where eastern rather than western culture and religion dominate the far future. Nonetheless, something about Lord of Light bothered me. As a child, I spent time in South East Asia, mainly in Singapore, but also in Bangkok, because my Dad was stationed there as an agent for the Norddeutscher Lloyd and DDG Hansa shipping companies. And while I cannot claim to know a lot about Hinduism and Buddhism (though two war-battered Buddha statues guard my home), I know enough to realise that Zelazny gets a lot of things wrong.

Of course, Zelazny isn't the only person to rather liberally adapt mythology into fiction. For example, The Broken Sword by Poul Anderson, Marvel's The Mighty Thor comics or The Ring of the Nibelungs by Richard Wagner are all liberal adaptions of Norse mythology and yet I am not bothered by them. However, hardly anybody worships the Norse or the Greek gods anymore, whereas Hinduism and Buddhism are living religions with some 255 and 150 million worshipers respectively. And borrowing from a living religion as someone who is not an adherent feels disrespectful in a way that turning Norse gods into superheroes does not.

I for one would love to see more science fiction and fantasy that draws on non-western culture and mythology. However, I would prefer to read works written by authors who actually come from the culture in question rather than by a Polish-Irish Catholic from Ohio. India is a country of 533 million people. Surely, some of them write science fiction and I hope to eventually see their take on Indian mythology and history rather than Zelazny's.

Interesting and well written but disjointed and somewhat disrespectful to half a billion Hindus and Buddhists.

Three and a half stars

Looting the Pharaohs: Easy Go by John Lange

I don't just read science fiction and fantasy, but am also fond of mysteries and thrillers. This is how I came across John Lange, who burst onto the scene two years ago with the heist novel Odds On and followed up with the spy thriller Scratch One last year. Both novels are notable for their tight writing and clever plots, as well as their evocative – and as far as I can tell accurate – description of locations deemed exotic by the average American reader. There even is the occasional science fiction element, e.g. the heist in Odds On is planned using a computer program.

Lange's latest novel Easy Go contains all the elements that made his previous works so enjoyable. This time, Lange takes us to Egypt, where an American archaeologist named Harold Barnaby has made an exciting discovery, a seemingly innocuous papyrus which contains an coded message revealing the location of a heretofore undiscovered royal tomb. This discovery could gain Barnaby academic accolades – or a whole lot of money. Barnaby chooses the latter and decides to rob the tomb. However, the timid academic needs help and finds it in Richard Pierce, a journalist and old war buddy of Barnaby's who has the connections and the plan to pull off the heist of the century.

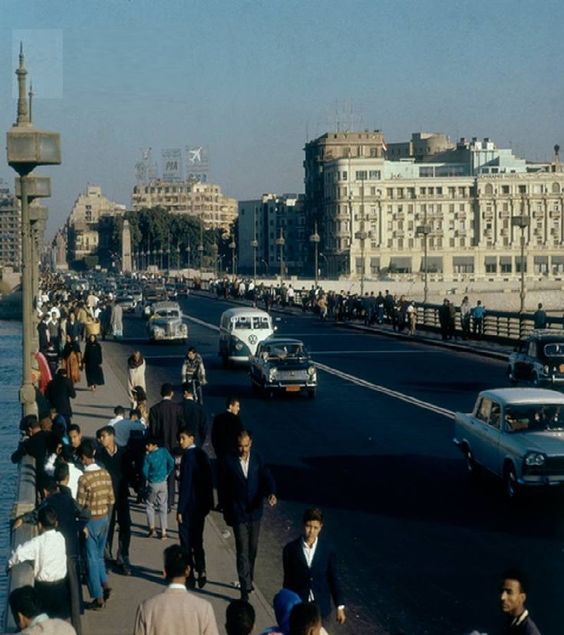

The novel follows the usual beats of a heist story. A team of specialists is assembled and a carefully plotted plan is executed, while fate keeps throwing wrenches at our protagonists, especially since the Egyptian authorities turn out to be not nearly as stupid as Pierce and Barnaby assumed. We have seen this sort of story before in movies like Ocean's Eleven, Topkapi or the TV-show Mission Impossible and yet Lange brings a unique flair to the well-worn plot via his knowledge of Egyptology and his vivid descriptions of bustling modern day Egypt (which contrary to popular belief does not look like the set of a Hollywood sword and sandal epic). The building of the Aswan Dam and the moving of the Temple of Abu Simbel play a notable role.

But who is John Lange? Rumour has it that he is a medical student at Harvard who is writing under a pseudonym in order to finance his tuition. Rumour also has it that Lange is working on a bona fide science fiction novel about a deadly plague from outer space, which is expected to come out next year. I can't wait.

An fun caper thriller which will make you want to book a trip to Egypt.

Four and a half stars

by Victoria Silverwolf

Tuning Up the Orchestra

I recently read a quartet of new works of speculative fiction. They range from so-called Hard SF, dealing with science and technology, to New Wave experimentation. Like the movements of a symphony, they offer varying contents, moods, and tempos. Let's grab copies of the program notes and find some good seats before the music begins.

First Movement: Andante

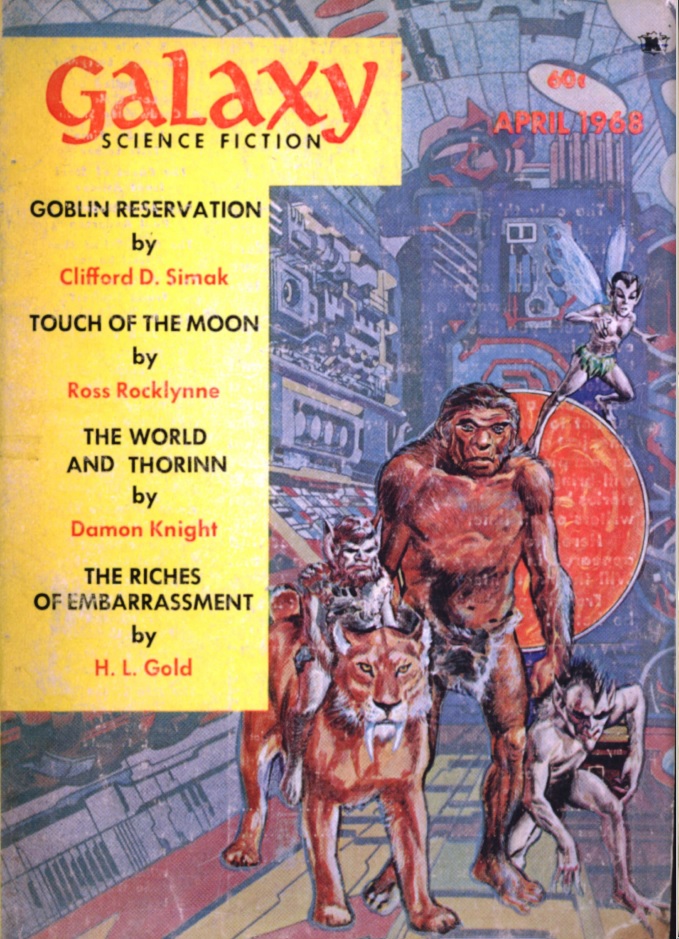

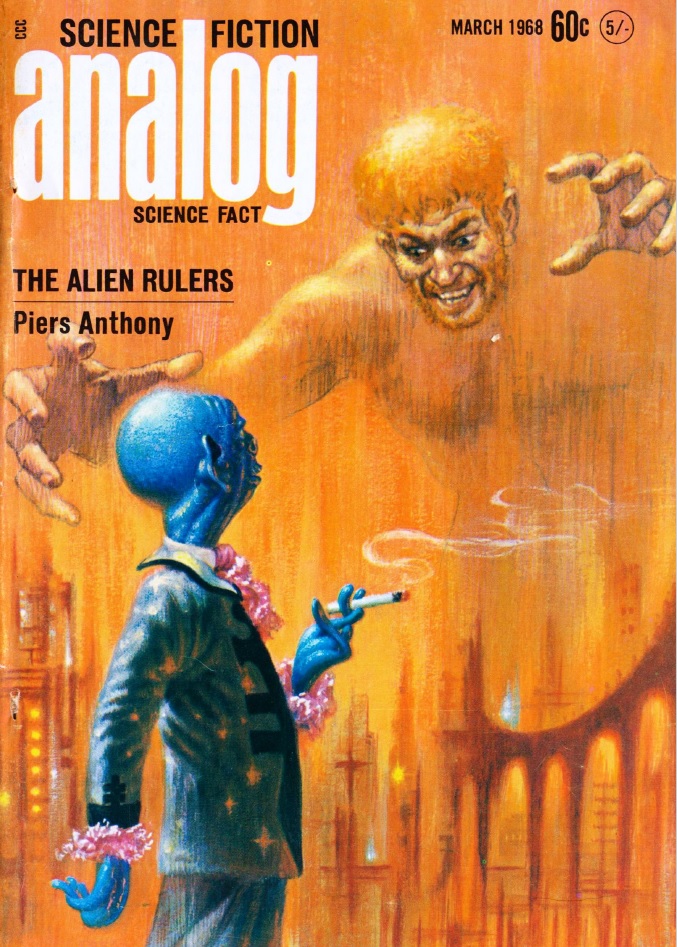

Anonymous cover art.

Out of the Sun, by Ben Bova

An American fighter plane traveling at three times the speed of sound over the Arctic Ocean suddenly breaks apart. The same thing happens to two other aircraft of the same kind. The military calls in the fellow who designed the special metal alloy from which the planes were constructed. He has to figure out what's wrong before more lives are lost.

This is a very short book with plenty of white space. I suspect it was intended for younger readers. (Unlike most so-called juveniles, however, all the characters are adults.) There are some violent deaths, but never described in any detail. The closest thing to sex in its pages is the hero taking a woman out to dinner.

This problem-solving story wouldn't be out of place in the pages of Analog. (Fortunately, it lacks John W. Campbell's quirky obsessions.) It moves at a moderate pace, but is never very exciting. You might be able to predict the main plot gimmick before it's revealed, if you've been keeping up with recent developments in technology.

The writing is very plain and simple. You could easily finish the book in an hour. A longer version, with more fully developed characters, would be welcome.

Two stars.

Second Movement: Adagio

Cover art by Robert Korn.

The God Machine, by Martin Caidin

This one starts with a bang. The narrator, having survived multiple attempts on his life, allows a woman with whom he's been having an affair to enter his room. She immediately offers her body to him, thrusting herself at him wantonly. Instead of reacting the way you'd expect, he knocks her unconscious with the butt of his pistol.

No juvenile novel here!

A long flashback tells us how he got into this situation. The narrator is a mathematical genius. The government contacts him while he's in high school, offering to pay for the best possible college education. In return, they want him to work on a hush-hush project.

It seems that millions of dollars of taxpayer money have been spent constructing a facility deep inside a mountain in Colorado. In terms of secrecy and security, it's the equivalent of the Manhattan Project. The goal? To build a super-powerful computer, one that can come up with its own ideas of how best to prevent a nuclear war.

The computer can also directly communicate with human beings through the use of alpha waves in their brains. Add in the fact that, along with the rest of its vast knowledge, it understands a lot about hypnosis, and you can see where this is going.

When the machine decides that the narrator has to be eliminated, things seem hopeless. He can't trust anybody. The computer itself is protected by lasers, electricity, and radiation. It's got its own secure atomic power generators, so you can't just turn it off. What's a fellow to do?

Other than the opening and closing scenes, most of the book moves at a leisurely pace. In sharp contrast to Bova's slim volume, this tome is well over three hundred pages. It could benefit from some judicious editing; I learned more than I really needed to know about the narrator's life before he becomes the computer's target.

Two stars.

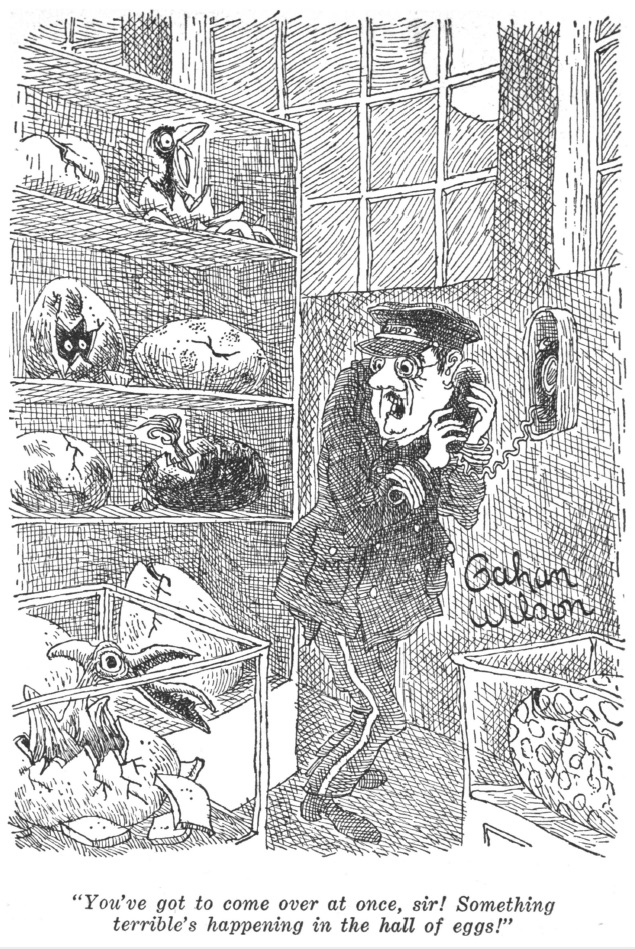

Third Movement: Scherzo

Cover art by Richard Powers.

The Reefs of Earth, by R. A. Lafferty

As soon as you take a look at the table of contents for the author's first novel, you know you're in for something different.

Not only are the chapter titles weird, they form a poem. There are lots of other little bits of verse throughout the book as well. Usually, these are poems that the six children (or seven, if you count Bad John) use to work magic, particularly to kill people.

But I'm getting ahead of myself, and I'm confusing you. Let me start over.

Some time ago, two married couples came to Earth from another planet. They're doomed to succumb to Earth sickness. They had a total of six children (or seven, if you count Bad John) among them. Because these offspring were born on Earth, they won't get the sickness.

What's this Bad John nonsense? I hear you cry.

Well, he died at birth, but he's still around. Only certain Earth folks, such as an American Indian and a drunken Frenchman, can perceive him. He's insubstantial and can pass through walls and such, but the other children are emphatic that he is not a ghost.

I have no idea why he's called Bad John. Another of the kids is just named John.

This gives you a tiny hint of how eccentric this book is. I would be hard pressed to provide a coherent plot summary. It has something to do with the children plotting to kill everybody on the planet. Meanwhile, one of the adults is blamed for a murder he didn't commit.

The narrative style is that of a tall tale or a shaggy dog story. The mood might be described as serious whimsy. There's a lot of violence — the basic plot, if there is one, involves an ax murder — but only the Earth people seem to care very much about it. It's not exactly a black comedy, but it treats death in an offhand fashion.

Although they're from another planet, the characters are more supernatural than alien. (They're called the Puka, and the allusion to the Pooka from Celtic myth seems intentional.)

It may be labeled as science fiction, but this is a fantasy novel, and a very strange one at that. How much you get out of it will depend on whether or not you're willing to let the author take you on a dizzying journey with no particular destination in kind.

Four stars.

Fourth Movement: Allegro

Cover art by Harry Douthwaite.

The Final Programme, by Michael Moorcock

As editor of a remarkably transformed version of the venerable science fiction magazine New Worlds, the author proves himself to be the guiding light of the British New Wave. This book shows he can write the stuff, too.

It first appeared as three separate stories in New Worlds. I'm not sure how much has been added to it, if anything, or how substantially it's been revised, if at all. It's more coherent as a whole rather than in bits and pieces, but it's still somewhat episodic.

Jerry Cornelius is a rock star, a brilliant scientist/philosopher, and as quick with a gun as James Bond. He's also a snappy dresser. We'll get a lot of detailed descriptions of his mod outfits throughout the book.

Jerry gets involved with some folks who want to get their hands on microfilm kept secure in the fortress home of his late father. Complicating matters is the presence inside the house of Jerry's sinister brother Frank and his beloved sister Catherine.

(The relationship between Jerry and Catherine may remind you of a certain controversial story that recently appeared in a groundbreaking anthology.)

Things get pretty wild at this point, from a bloody assault on the fortress to a secret underground base built by the Nazis to the novel's truly apocalyptic climax.

I should mention another character who plays a vital part in the story. Miss Brunner (no first name ever given) is an enigma. At first, she seems to be nothing more than one of the conspirators who work with Jerry. She soon turns out to be a most peculiar sort of person indeed.

I'd say Miss Brunner is actually the heart of the novel, more so than Jerry himself. She's always several steps ahead of everyone else, and has an agenda of her own that doesn't become clear until the end of the book.

The author's style is usually surprisingly traditional, no matter how bizarre the plot. The mood combines frenzy with the feeling that things are falling apart all over, and that maybe this is a good thing. At times, I felt that Moorcock was amusing himself at the expense of the reader. It's worth a look, but you may wonder what it's all supposed to mean.

Three stars.

by Gideon Marcus

Ace Double H-48

The Youth Monopoly, by Ellen Wobig

Rod Dorashi is a vagabond, a member of the wretched working class of Metropolis, staying out of trouble so as not to be squashed by the draconian dictator Korm. Yet he risks all to take in an old man, hit by a car, in his last hours of life. The dying man presses a packet of seeds upon Rod, promising that they are the secret to eternal life.

Enter Bey Ormand, a slick powerful man who is the founder and ruler of Trysis–a paradisical resort and the sole purveyor of the distilled essence of the forever seeds. For a lordly sum, they turn back the clock for their customers by five years. Seemingly without motive, Ormand picks up Rod and adds him to his select coterie of multi-centenarians. The troupe then acts as little dictators, forcing all invitees, whether petty princes of a Balkanized America, or faded stars and starlets, to grovel at their feet.

Despite an instinct for rebellion, Dorashi never quite revolts. Instead, he sticks with the sadistic Ormand and his band for centuries. When they leave (almost without notice), the wrap-up is many pages of explanation: turns out Ormand et. al. were not very old humans but actually very old aliens, and the goal of the project was to siphon off the wealth of the Earth–something they've done time and again.

The whole thing reads like a long, unpleasant cocktail party, and the framing of the ending is not at all condemnatory. It merely is.

I applaud new author Wobig for their first publication, but I found The Youth Monopoly a difficult, and ultimately unrewarding, read.

Two stars.

Pictures of Pavanne, by Lan Wright

On the dead planet of Pavanne, light years from Earth, reside 'The Pictures'. This tremendous tapestry, carved from native rock by unknown aliens countless eons ago, are the most beautiful sight in the galaxy. And, of course, capitalism being what it is, the Harkrider corporation has secured the license to the their viewing. Now, Pavanne is a pleasure planet that specializes in relieving every wealthy guest of their money, pouring it into the coffers of the half-robotic, entirely wizened Jason Harkrider.

Enter Max Farway, one of humanity's leading artists. Driven by the need to prove himself, exacerbated by the twisted, diminutive and sterile body he was born with, Farway resolves to tackle the hardest subject of art: The Pictures themselves. And so, he travels to Pavanne with his beautiful, recently widowed step-mother, and his much put-upon agent, in time for the conjunction of the alien planet and the brighter of its two suns–when the artifact achieves its highest, and most ineffable level of beauty. But once he steps foot on Pavanne, Farway finds himself in a power struggle with the planet's venal warlord, with Harkrider's assistant, Rudolph Heininger, a wild card in the conflict. At the heart of it all are the unknown predictions of the murdered mathematician Damon Wisehart, whose calculations suggest something terrible is soon to occur involving Pavanne and its extraterrestrial art.

For a good portion of the reading, I admired author Wright's juxtaposition of the petty and irritable Farway, along with the thoroughly disgusting Wisehart (and his twisted twin daughters), with the unearthly beauty of The Pictures. As Farway slowly grows up under the ministrations of his gentle step-mother, I looked forward to a piece that was largely philosophical, eschewing the fetters of the typical Ace Double. This is largely discarded at the end, as things wrap up suddenly and with much action, but without much heart.

Perhaps a more satisfying book remains to be published by a different press. As is, I give it three stars.

Need more science fiction? The next episode of Star Trek is on TONIGHT! You won't want to miss it:

Here's the invitation!

![[March 16, 1968] In Distant Lands (March Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/680316covers-672x372.jpg)

![[March 14, 1968] Bugs in the machine (<i>Star Trek</i>: "The Ultimate Computer")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/680314title1-672x372.jpg)

![[March 12, 1968] Be Seeing You (<i>The Prisoner</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/680312a-672x372.jpg)

![[March 8, 1968] Inglorious (<i>Star Trek</i>: "The Omega Glory")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/680308title-672x372.jpg)

![[March 6, 1968] Trend-setter (April 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/680306cover-672x372.jpg)

![[February 26, 1968] Stormy Weather (March 1968 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/680226cover-672x372.jpg)

![[February 22, 1968] Reich or Wrong? (<i>Star Trek</i>: "Patterns of Force")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/680222title-672x372.jpg)

![[February 20, 1968] 1-2-3 What are we fighting for? (March 1968 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/680220cover-671x372.jpg)

![[February 18, 1968] Yet(i) Again, London Is Under Attack (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Web Of Fear [Part One])](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/680218underground-672x372.jpg)