For your reading pleasure, Galactic Journey presents a quintet of the newest books in this month's Galactoscope…

by Victoria Silverwolf

The Prodigal Sun, by Philip E. High

I'm sitting here sipping some Earl Grey tea, nibbling a Bendicks Bittermint, listening to the Beatles on the radio; am I still in Tennessee? I must be, because I'm holding Ace paperback F-255 in my hand, and that's an American publisher. Then I take a closer look, and notice that the author is British. I guess there's no way of getting around it; I'm a walking anglophile.

Philip E. High may not be very well known to those of us on this side of the Atlantic, but his stories have appeared in UK publications for about a decade. I've had a chance to read a handful of them in New Worlds, thanks to fellow Traveler Mark Yon, who is very generous with lending copies of the magazine to Yanks.

High also had the story Fallen Angel published in the June 1961 issue of Analog. Our host was not impressed by it. Overall, High seems to be a competent, if undistinguished, writer of science fiction. Will his first novel confirm that opinion? Is it worth forty cents? Let's find out, starting with the front cover.

Was he there to teach Earth – or to rule it?

Well, that's a fairly interesting teaser. The cover art is all right, I suppose, although it doesn't really grab me. Let's take a look inside.

They wanted his secrets, but feared his presents

That should say presence, I think.

Next we have a cast of characters. That's a nice touch, as it allows me to flip back to the front when I forget who somebody is. My only complaint is that it leaves out some important names. Anyway, let's move on to the text. Like most science fiction novels, it's well under two hundred pages long, so it's not a major investment in time.

The background is complex, requiring a lot of expository narration and dialogue. Long before the novel begins, Earthlings settled a few extra-solar planets. They ran into aliens, at about the same level of technology, who wanted one of these worlds for themselves, and a long and bloody interstellar war followed. Eventually the humans won, but only at the cost of turning Earth into a brutal dictatorship. Anyone suspected of disloyalty undergoes involuntary psychological conditioning, so that rebellious thoughts cause intense physical pain.

Into this dystopian world comes our hero, a young man named Peter Duncan. As an infant, he was the only survivor of an accident in space, and was rescued by highly advanced aliens. The rulers of Earth see him as a potential threat, but also as a possible source of technological secrets. He has plans of his own, which I won't describe here, as they are not fully revealed until the end of the book.

The complicated, fast-moving plot also involves a bodyguard, a reporter, and a businessman who undergo important changes in their relationship with Duncan. Thrown into the mix are enemy aliens, held as prisoners of war after hostilities end. There is also a secret underground civilization, a love interest for the hero, and yet another set of aliens. The novel shifts point of view often, sometimes several times within a single scene.

Near the end, developments come at a furious pace. The revelation of Duncan's scheme, and the explanation of the novel's punning title, go beyond the limits of credulity.

The book is full of interesting ideas; maybe too many. Its basic theme can be expressed as Love Conquers All, which is not what you expect from a science fiction adventure story. Many of the secondary characters are intriguing, although the protagonist is rather bland. Often a villain turns out to be more complex than first thought, and earns the reader's sympathy. The author's style is serviceable at best, with some clumsy phrasings. Overall, it's a mixed bag, worth reading once, if you can spare a quarter, dime, and nickel, but not destined to become a timeless classic.

Three stars.

The Wanderer, by Fritz Leiber

by Jason Sacks

Cover by Bob Abbett

The Wanderer by Fritz Leiber is an odd book, a combination of two disparate elements which never quite come together for me.

The core plot of the story is that a new planet, nicknamed the Wanderer, has appeared in our solar system — and in fact appears in almost exactly the same spot as our moon. At first nobody knows what to make of this new celestial body, but most people feel a combination of awe and confusion about what this new interstellar visitor might mean and what its impact might be on our world.

Quickly, though, a tragedy which once was unimaginable becomes inevitable. The moon begins to disintegrate under the gravity of The Wanderer, which unleashes a devastating level of natural destruction. Because The Wanderer has a higher gravity than the moon, ocean tides increase geometrically in power, terrible tidal waves hit all oceans, earthquakes strike in California, rising ocean currents open Lake Nicaragua to the ocean, and floods strike much of the United Kingdom.

In the midst of this utter destruction, Leiber shows us the hearty survivors who battle the effects of the devastation. We follow a band of travelers in Florida who encounter unexpected racism, a group of UFO enthusiasts in California who battle tsunamis, violence and some actual flying saucers, a lunar explorer who sees the crisis up front, and a panoply of other ordinary and extraordinary people, from South Africa to Vietnam to New York to a lone sailor piloting a ship across the Atlantic.

The scenes with these characters provide The Wanderer with much of its power and momentum, as readers are swept up in the terrifying and all-too-human adventures of these hearty and terrified people. In fact, if Leiber had focused exclusively on the people and left the reason for the destruction a mystery, this might have been an even more satisfying book.

Instead, Leiber shows us the reason for the Wanderer’s presence. In those sections, the book falters. The reason the Wanderer journeys to our solar system is that the Earth is one of the remaining backwaters in the universe that’s not yet settled by a group of extraterrestrial beings looking to civilize nearly all of known space. Those beings need to use our solar system as a kind of refueling station.

The Wanderer is actually an artificial planet, filled with hundreds of levels of civilizations inhabited by creatures and cultures nearly unimaginable to most humans. Piloting the ship is a super-brilliant catlike creature named Tigerishka who captures one of the lunar explorers and explains to him the background of the plot. A rebel against the civilizers, Tigerishka is soon captured and put on trial before she runs away from her fate — but not before she and the human have some extraterrestrial intercourse.

Leiber spins up an epic tale with some memorable characters and startling situations, but the work feels a bit undercooked to me. The two key elements of the plot never quite connect with each other and the space trial comes from out of nowhere. There is precious little foreshadowing of Tigerishka’s presence, and I found the idea and execution of her to be a bit pulpy. I kept imagining the cover being similar to a Gernsback pulp with an attractive human body attached to a mysterious feline face.

Still, this is the kind of epic novel which would make for a fine film and likely a nomination for the award named for Mr. Gernsback. While I won’t be voting for it in next year’s Hugos, it’s easy see Mr. Leiber’s entertaining though flawed creation taking home honors.

Rating: three stars

[you can purchase this book or check it out at the library]

Marooned, by Martin Caidin

by Gideon Marcus

Some science fiction propels us to the farthest futures and remotest settings. The latest book by Martin Caidin, better known by his aeronautical and space nonfiction, takes place on the very edge of tomorrow. When the Soviets stun the world early in 1964 with the launch and docking of a pair of multi-crew spacecraft, NASA is directed to fill the space between Gordo Cooper's last Mercury flight and the increasingly delayed Gemini program. Major Richard Pruett, a (fictional) member of the second cadre of astronauts, is tapped for a 49 orbit Mercury endurance mission, launched in July.

For three days, all goes perfectly, but at the moment of deceleration, Pruett's retrorockets refuse to fire, stranding the fellow in space. Now, with just enough oxygen to last two more days, the hapless astronaut must somehow find a way to last three days — until the drag of the upper atmosphere seizes Mercury 7 and sends it plunging toward the Earth.

There is no question but that Caidin did his homework for the book. Undoubtedly, the author has enough material for a lengthy reference on the Mercury program and the astronaut training process in general. But within the gears and hard science, Caidin manages to draw a compelling profile of Pruett, sort of an amalgam of the seven Mercury astronauts. From his first flight in a propeller plane, through a bloody stint in Korea, and past the rigorous astronaut indoctrination, Pruett gives the reader a first-person view of the experiences that make up the humans beneath the silver sheen of the spacesuit.

Marooned shines most brightly in the first and last thirds of the book. The solitude and hopelessness Pruett's plight is vividly portrayed, and the pages fly up through about page 100. The journey through astronaut training is more clinical, with few dramatizations to liven it up. It will be interesting to neophytes, but any of us who read the Time Life series on the Mercury 7 (or the compilation We Seven) will find it dry. Things pick up again when we learn of the daring rescue attempts being assembled to save Pruett from being America's first casualty in space.

With Marooned, Caidin accomplishes two goals in one book, delivering an exciting read and providing perhaps the most detailed summary of the Mercury program for the layman yet put to paper.

Four stars.

ace double F-261

The Lunar Eye, by Robert Moore Williams

Cover by Ed Valigursky

It is the year 1973, and Art Harper owns a service station on the freeway to the launch pad where soon a giant rocket will take the first twelve men to the moon. His life had hitherto been one of complete and deliberate normality. But then, a woman appears claiming to be one of the Tuantha, a society of humans that had gone to the moon millennia before and established a secret, highly advanced civilization. She insists that Art is Tuanthan, too, placed with a human family like a changeling, and that he must come home. Further complicating the mix is Art's brother, Gecko, who, while human, managed to sneak into the Tuanthan moon city during one of the frequent inter-planet teleport trips. Now he wants to live in their lovely settlement, too.

The fly in the ointment is the upcoming lunar shot. The Tuanthans are convinced that, should the two societies ever meet, the Earthers will dominate and ultimately exterminate them, just as the Europeans slaughtered the American Indians. And so, the Tuanthans plan to sabotage the American lunar effort before the moon city is discovered.

This latest book by Robert Moore Williams stands in stark contrast to Caidin's hyer-realistic Marooned. Moore has been producing adventure stories since the '30s, and it shows. Eye reads like something written in 1948, lacking any comprehension of technological improvements since then. But the real flaws of the book are in its execution. It starts out excitingly enough, and the first half reads quite quickly. But then Art, Gecko, and the Tuanthan, Lecia, end up on the moon, and the whole thing becomes a slog of speeches and redundant scenes as the three are put on trial for treason for wanting to stop the destruction of the American moon rocket.

In fact, Williams' fiction production consists almost exclusively of novellas. It's pretty clear he has no heart or endurance for longer works, and the padding required to cross the novel-length finish line is tiresome and obvious. Finally, Eye is riddled with plot holes and story threads that go nowhere.

A promising but ultimately sloppy piece: Two and a half stars.

The Towers of Toron, by Samuel R. Delany

Cover by Ed Emshwiller

On the other hand, Chip Delany's new work, a sequel to last year's Captives of the Flame, reflects an upward trend. In the first book of the series, he introduced us to Toromon, capital of an island empire situated on Earth long after an atomic cataclysm. The cast of characters was bewilderingly large: the decadent and young King Uske, his cousin; Prince Let, who was smuggled into the custody of the smarter, psionically gifted forest people; the capable and canny Duchess Petra; the noble and former prisoner, Jon, who along with Petra had been rendered invisible in dim light by the radiations that girdle Toron's imperial boundaries; the paternal forest person, Arkor; Tel, a poor fisherman's son; Alter, a thief and acrobat; Clea, a brilliant mathematician…

It was all a bit much, but now that I see the author is planning on doing more with the world, I can understand why he introduced so many players. Towers does a fine job of continuing their stories, and I feel like I have a good handle on them all now.

Towers is set three years after Flame. The empire has rediscovered the technology of matter transfer and is busy exploring the devastated planet. A war has already been fought and won against the mutant insectoid tranu, and another is in progress against the mysterious ketzis. It is a strange war, fought in nearly impenetrable mists thousands of miles from home. The enemy is never seen, and its combatants (who include Tel, the fisherman's son), seem almost in a daze, unable to dwell much upon their pasts or their futures. Meanwhile, Toromon is in increasing turmoil. Prime Minister Chargill is assassinated. The evil seed of the fiery enemy from the first book is discovered hidden in the mind of King Uske. And Clea, seeking refuge in arcane mathematics after the death of her fiancee (that occurred in Flame), discovers a secret that could tear the entire empire asunder.

Tower is a significant improvement on Flame: better paced, more skillfully written, exciting. It is no mean feat to juggle all of these viewpoints and still maintain a coherent whole. Moreover, I appreciate the sheer variety of characters, including the prominence of several women.

I did find both fascinating and a little disturbing Delany's depiction of the three races of people that inhabit future Earth, with greater divergence than the paltry skin tone differences humanity has today. They are practically different species, with the baseline humans being seeming to be more imaginative (though not necessarily smarter) than the "neo-neanderthals," and the forest people occupying a mental rung above the humans. The neo-neanderthals are referred to as 'apes', and though they don't ever object, I can only imagine that the author (who is Black) is making a point.

If there's a down-side to the book, it's that it is a clear bridge to the next novel in the series, which has not yet come out. All the threads do come to a satisfying resolution at the book's end, but the aftermath, and the coming (final?) battle with the cosmic Lord of the Flames is left for later.

Three and a half stars, and kinder disposition toward the first book.

[(this book and the others in the series can be purchased here)]

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[January 18, 1970] Below par (<i>The Long Loud Silence</i>, <i>Sex and the High Command</i>, <i>Beachhead Planet</i>, and <i>Taurus Four</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/700118covers-672x372.jpg)

![[July 22, 1966] Ridiculous! (August 1966 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/amz-0866-cover-665x372.png)

![[July 2, 1966] The Big Thud (August 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/IF-1966-08-Cover-644x372.jpg)

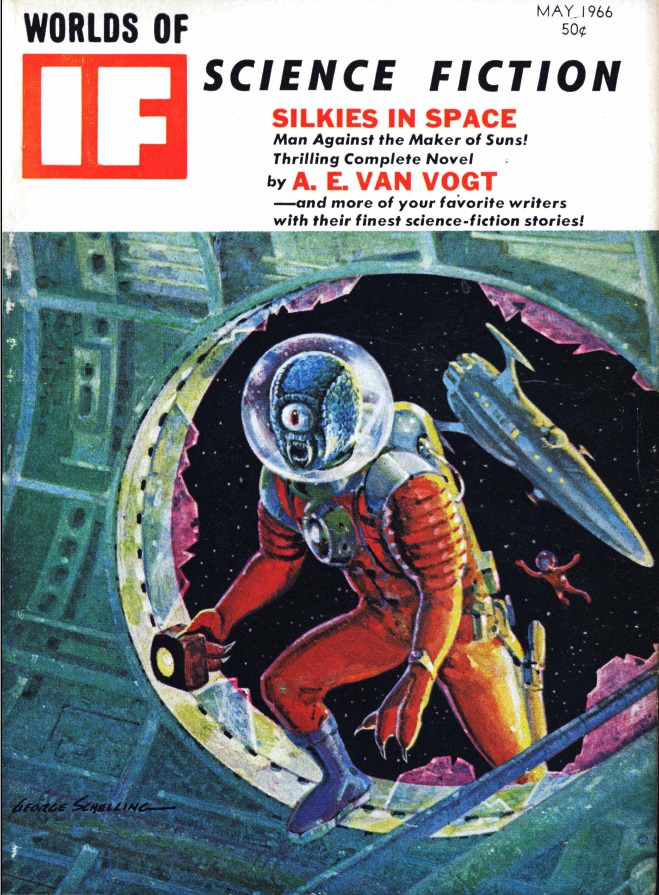

![[April 2, 1966] Hidden Truths (May 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/IF-1966-05-Cover-659x372.jpg)

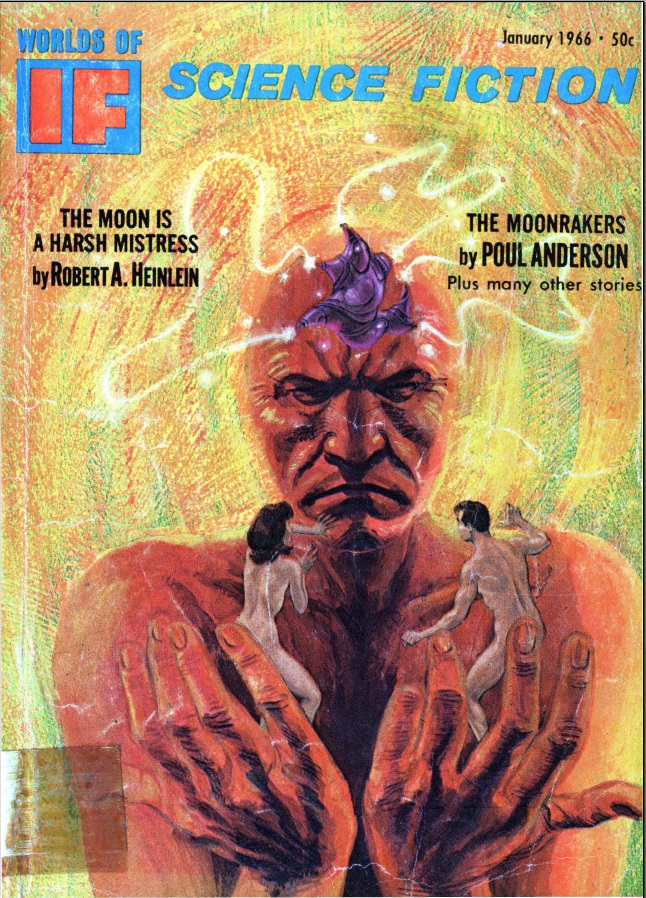

![[December 2, 1965] Superiority Complex (January 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/IF-1966-01-Cover-646x372.jpg)

![[September 6, 1965] War and Peace (October 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/IF-1965-10-cover-657x372.jpg)

![[March 29, 1964] Five by Five (March Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/640329marooned-1-417x372.jpg)