What defines Humanity?

When Androids are created to look and behave indistinguishably from humans, this question bears even greater importance.

The setting: Earth. The time: not too far from now. Rick Deckard is a man whose job is to “retire” escaped androids, using an empathy test to determine who is human and who is not. Most questions revolve around treatment of animals and only complete revulsion at the thought of eating meat or using leather made from an animal’s hide would allow someone to pass.

Ironic, given that I would not pass this test, and you, Dear Reader, probably wouldn’t either.

But these attitudes make sense in the context of Deckard’s world.

Survivors are few and far between on a nuclear-war destroyed Earth. Most humans have emigrated to a terraformed Mars. Animals no longer exist in the wild and what few creatures have evaded extinction are kept as pets and used as a sign of social status. Rick Deckard’s sheep shamefully died years ago, and since not owning an animal at all would mark him as inhuman, Deckard secretly replaced his animal with an ersatz electric sheep. Most of his motivation in this story is to acquire a new live animal to replace his fake one, and it’s this social pressure that leads him to taking on one last job before he leaves retiring androids behind him.

While hunting a dangerous group of runaway androids, Deckard is seduced by an android he meets earlier in the story – Rachael. Rachael so happens to share the same model as one of the targets and attempts to seduce him so that he will feel conflicted about killing his target.

I enjoy when sexuality is explored in science fiction, but the scene that follows was greatly uncomfortable for me to read. Don’t mistake me for being a prude, but Rachael’s body is described as pre-pubescent. Perhaps Dick meant to relay that she is lacking in shape or body hair, but I read it to be girlishly young. I believe the author’s intent might have been to relay to readers that this relationship is immoral, in which case, I think he succeeded.

While Deckard’s weakness towards androids is rooted in his sexual attraction towards them, there is another notable character who empathizes with the androids, but for a drastically different reason.

Because he scored too low on an IQ test, Isidore has been marked as “special,” meaning he isn’t allowed to emigrate to Mars or even procreate and overall is regarded as “lesser.” When the group of runaways Deckard is hunting hides out in Isidore’s otherwise abandoned building, he quickly allies with them, out of perhaps a mix of loneliness but also kinship.

I found Isidore to be the most compelling character in the book. Through him, Dick creates a strong irony. Humans feel superior over androids, priding themselves on the one thing they have that androids don’t – the ability to empathize – yet it’s ironic that Isidore, a human being, is actually treated worse than animals for his supposed lack of intelligence, while androids are most notable for being incredibly intelligent.

So what defines humanity? Dick offers no clear answers, but instead evokes several interesting discussion points that I am sure will stick with me for years to come. 5 Stars.

by Jason Sacks

I’ve raved about Philip K. Dick several times in these pages, full of praise for his kitchen-sink imagination and his unprecedented ability to build up worlds. The estimable Mr. Dick has done some astoundingly great work in the past, but his latest novel, which has the brilliantly odd title Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, is his best work so far.

The most pervasive theme in Dick’s writing is the idea that technology can't lift us up to a higher place. In fact, no matter how greatly our technology improves, humanity can never escape its own inner pathos. People will always be people, with all our multifaceted flaws, and we can never escape our basest motives.

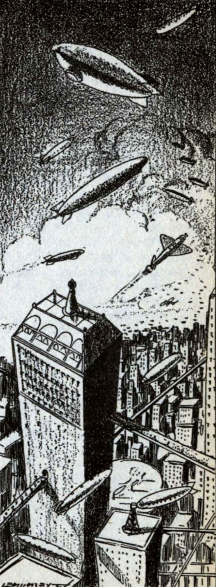

Do Androids Dream is set in an Earth which is living with the aftereffects of World War Terminus, a nuclear event which nobody quite knows who started, but which has caused utter devastation on our planet. Earth has mostly been deserted – most people have been killed by the war and its radiation, and those who weren’t killed or sterilized by the resulting fallout were transported off-planet to various planets, where a new civilization has emerged with andy (android) servants of “as many types as there were cars in the 1950s," a nice Dickian touch of verisimilitude.

It's also a nice Dickian touch for there to be so much uncertainty who started the War, and for nobody much to care about its origins. As he nearly always does, Dick concentrates on the ordinary people affected by the event and on their sad little lives of quiet desperation.

Our main character is a poor schlub named Rick Deckard, who we immediately learn is married to a woman who seems indifferent to him. Iran Deckard loves her Penfield Mood Organ, a device she uses to dial her mood to a six-hour self-accusatory depression (or an awareness of the manifold opportunities open to her in the future, to help her break out of the depression). Rick and Iran bicker and fight, about her love for the Penfield, about Rick’s love for his animal, and about why the couple couldn’t emigrate from Earth. Iran is a pretty typical wife in a Dick novel – we’ve seen him write shrewish women since his nongenre novels of the 1940s – but this wife has some agency about her, some inner life which shows an emotional complexity beyond some of the more impulsive women Dick has written in previous works.

Like most of the people who live in this devastated San Francisco, Deckard is captivated by the idea of owning an animal. In a world devastated by war, an animal is a precious commodity. But Deckard can’t find an actual living animal to buy, at least not anything he wants to buy or remotely in his price range.

So Deckard has to buy an artificial animal, a robotic sheep, to take place of his sad living sheep who died of tetanus. Deckard is obsessed with the pathetic nature of his robotic animal, desperate to own a real living animal as a status symbol to make his life more fulfilling. If he earns enough credits on his job, Deckard might be able to buy a bovine creature, perhaps a cow, if he can pick up a well-paying job.

Deckard works as a kind of android hunter, in fact. See, andys from the colonies have returned to the Earth, and Deckard is paid a commission to hunt down and bag the andys. But it can be hard to tell the difference between the andys and the real people. The only easy way to tell the difference is through an understanding of empathy. The Voight-Kampff scale tests empathy; when Deckard’s predecessor tried to use the scale on an andy, he was brutally killed for his efforts. Thus, taking on this bounty hunter case is a test for Deckard in a truly existential way – both his sense of his own humanity and his very life are under threat.

Humans exist in a constant cloud of empathy. Deckard feels things, often too deeply. He lives in a world of envy and object lust, of self-pity and pathos.

He’s even part of a fascinating pseudo-religion called Mercerism whose practices are based all around the creation of a kind of empathy in its followers. Followers of Mercerism connect themselves to a kind of universal shared device which allows them to psychically feel each other as well as feeling empathy for all of Mercer’s struggles as be battles his way up a hill while being pelted with rocks from some unknown force. There’s an element of the passion of the Christ in Mercer's struggles, as this near universal connection and sacrifice connects all the believers to each other in a transcendent way.

Opposing Mercer is Buster Friendly, the always-on, always smirking TV personality who has an unbreakable influence on everybody on both Earth and the colonies. Buster interrupts his endless blather with a diatribe against Mercer – and the way that whole storyline plays out is tremendously interesting.

Our secondary protagonist here, John Isidore (see Robin's article above for her insightful views of him), is a major follower of Mercerism, and the way this religion spans class and intelligence is a fascinating element of Dick's tale. In the future, it seems culture is monololithic and controlled by unseeing, unknown people for reasons scarcely pondered – a fascinating black hole in this most complex novel.

And, wow, there’s just so much else here that’s rich and intriguing. The book touches deeply on the concept of entropy, with Deckard acting as a kind of force that continually unmakes the world around him. Crucial to the ideas of the book is the idea of kipple, the slow entropy and destruction of everything mankind made. Deckard is a kind of human version of kipple, causing the dissolution of all of mankind’s aspirations.

There are nods to the arts, and to real human love, and there are some beautiful passages about human loneliness and this is all written in such lovely, simple, precise prose.

And the ending does so much to cast the entirety of this rich, complex world in a different light. The ending of this novel has a profound effect on what happened previously and leaves a powerful aftertaste for the reader.

Do Android Dream brings so many thematic lines to the surface in so many ways, with so many different approaches, that the writing approaches true profundity.

What does it mean to be human when your emotions are regulated, when your passions are sublimated into hobbies, when you’re mistreated by others, when even the very basic nature of humanity is nullified by the concept of artificial beings indistinguishable from real people? Is it inherent in being a human being to feel base emotions but to also seek the kind of transcendence that Mercerism provides? Is it really our empathy that makes us human? Does it decrease our humanity to have to dial up emotions or does it enhance that same humanity? Are all our petty goals and aspirations unimportant when our shared sacrifice for Mercer makes individuality feel almost subversive? In the end, what does it mean to be human at all?

And all of this brilliant philosophy is delivered in a beautifully written novel of a mere 170 compulsively readable pages.

This is Philip K. Dick’s finest work so far. 5 stars, and a clear contender for a Galactic Star of 1968.

![[March 18, 1968] What Defines Humanity? (<i>Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/680318cover-scale-2_00x-506x372.jpg)

![[October 10, 1967] Jack the Ripper and Company (<i>Dangerous Visions</i>,Part One)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/1967_Dangerous-Visions-hc-2-672x372.jpg)

![[July 16, 1967] The Weird and the Surprising (July 1967 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/670716covers-672x372.jpg)

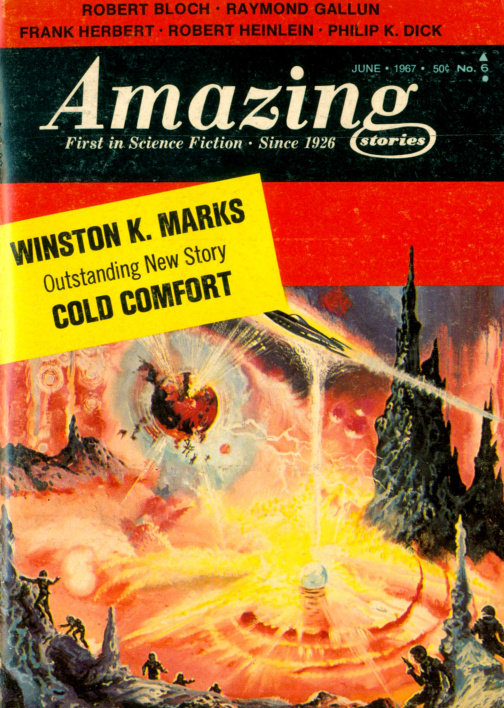

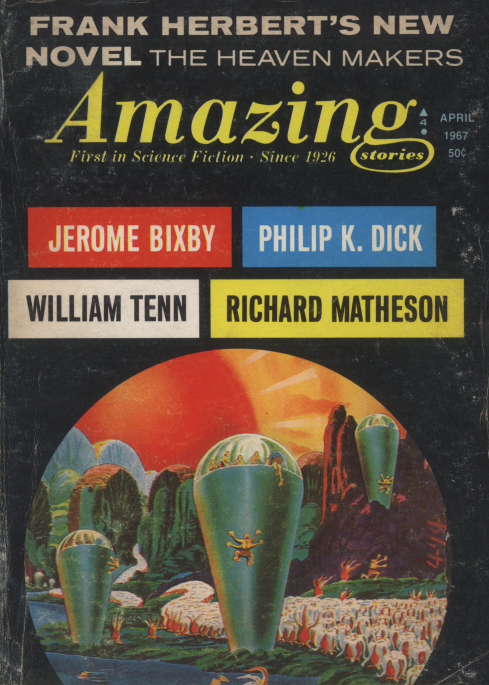

![[May 6, 1967] Stirred? Shaken? (June 1967 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/amz-0667-cover-504x372.png)

![[March 14, 1967] Family Matters (April 1967 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/amazing-apr-1967-cover-489x372.png)

![[February 18, 1967] Six! Count them — Six! (February Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/670218covers-672x372.jpg)

![[November 24, 1966] Middling (December 1966 <i>Amazing</i>)</big></b>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/amz-1266-cover-503x372.png)

![[October 16, 1966] Only the Lonely (November 1966 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/fantastic_196611-3.jpg)

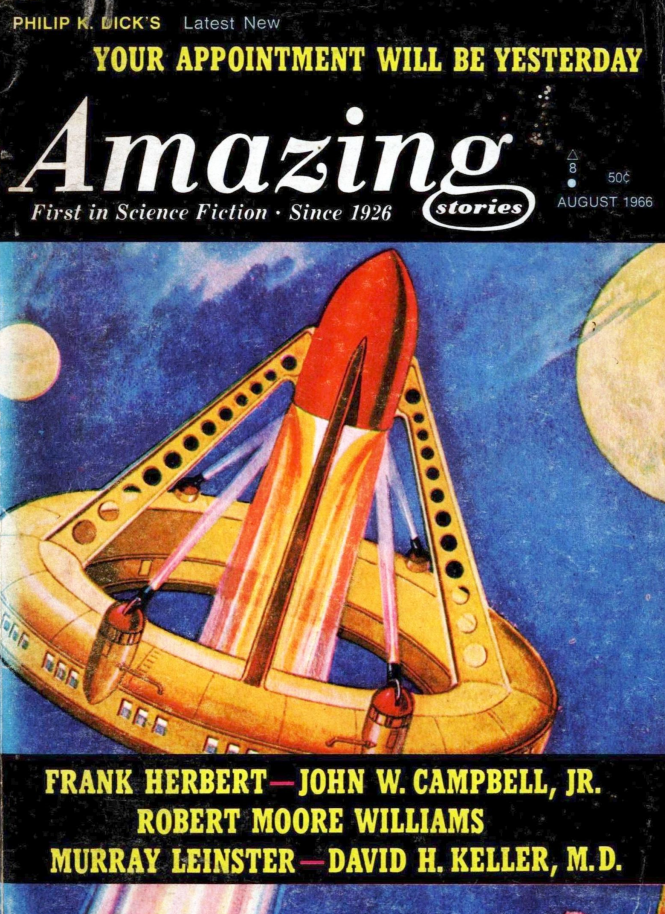

![[July 22, 1966] Ridiculous! (August 1966 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/amz-0866-cover-665x372.png)

![[March 22, 1966] Summer in the sun, winter in the shade (April 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/660320cover-672x372.jpg)