by John Boston

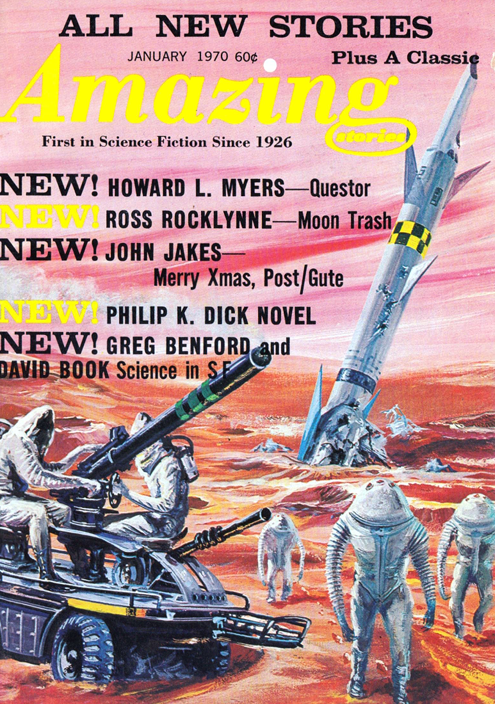

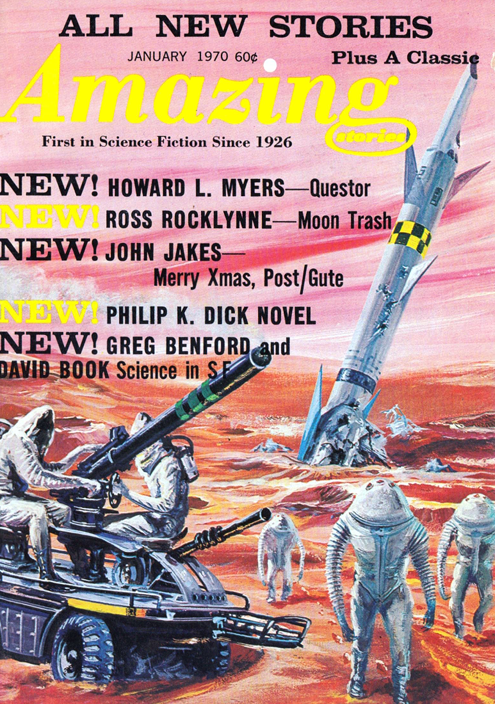

The January 1970 Amazing continues in its newly-established course—“ALL NEW STORIES Plus A Classic”—though it’s fronted in the all-too-long-established manner, with another capable enough but generic cover by Johnny Bruck, reprinted from a 1965 issue of Perry Rhodan. Editor White has acknowledged this practice and, I suspect, is looking to end it when circumstances and the publisher permit.

by Johnny Bruck

The usual complement of features are here, starting with a long editorial meditation about the Moon landing, reactions to it, the progress (or lack thereof) of technology generally, and a note of cogent pessimism about the future of the space program: we can do it, but will we? The book reviews continue long and feisty, with White slagging James Blish’s generally well-received Black Easter, concluding: “At best, then, Black Easter is not a novel, but only an extended parable. At worst, it is a tract. In either case, it pleads its point through the straw-man manipulations of its author in a fashion I consider to be dishonest to its readers.” The milder-mannered Richard Delap says that Avram Davidson’s The Island Under the Earth “isn’t a horrid book like some of the dredges of magazine juvenilia we’ve seen recently; it’s soundly adult and imaginative but just too uneven and incomplete to be a good one.” Damning with faint praise, or the opposite? New reviewer Dennis O’Neil, a comic book scripter and “long a friend of SF, and a one-time neighbor of Samuel Delany,” compliments Thomas M. Disch’s Camp Concentration: “Of all the adjectives which might be applied to Camp Concentration—‘artful,’ ‘brilliant,’ and ‘shocking’ come to mind—maybe the most appropriate is ‘heretical.’ ” He then reads the book in terms of Disch’s assumed religious background. “Catholicism is a hard habit to kick. James Joyce didn’t manage it, and neither does Tom Disch.”

The regular fanzine reviewer, John D. Berry, is on vacation, so White turns the column over to “Franklin Hudson Ford,” apparently a pseudonym of his own, for a long and praiseful review of Harry Warner’s fan history All Our Yesterdays. The letter column is even more contentious than the book reviews, with one correspondent addressing “My Dear Mr. Berry: You and your coterie of comic-stripped idiots” (etc. etc.). John J. Pierce, he of the “Second Foundation” and denunciations of the New Wave, explains that he really does have some taste: “If the romantic, expansive traditions of science fiction are to be saved, they will be saved by the Roger Zelaznys and the Ursula LeGuins, not by the Lin Carters or the Charles Nuetzels”—a point I had not realized was in contention. William Reynolds, an Associate Profession of “Bus. Ad.” at a Virginia community college, tries to correct White about the operation of the Model T Ford and provokes a response as spirited as it is mechanical. One Joseph Napolitano complains about “new wave stories”: These new wave writers “don’t want to work. Its [sic] not easy to come up with an idea for a story and they just don’t want to take the time and use what little brains they have to do this.” (Etc. etc.)

After all this amusing contention, it is unfortunate to have to report that the fiction contents of this issue are pretty lackluster.

A. Lincoln, Simulacrum (Part 2 of 2), by Philip K. Dick

I’m a great admirer of Philip K. Dick’s best work, and some of his less perfect productions as well. So it’s painful to report that A. Lincoln, Simulacrum, is a bust. It has its moments, but there aren’t enough of them and they don’t add up to much, even though the novel’s themes reflect some of Dick’s long-standing preoccupations.

Protagonist Louis Rosen is partner in a firm that manufactures and sells spinet pianos and electric organs. But now his partner Maury is branching out into simulacra—android replicas of historical persons, designed by his daughter Pris. They’ve started with Edwin M. Stanton, President Lincoln’s Secretary of War. How? “. . . [W]e collected the entire body of data extant pertaining to Stanton and had it transcribed down at UCLA into instruction punch-tape to be fed to the ruling monad that serves the simulacrum as a brain.” Ohhh-kay.

More importantly, why? Because Maury thinks America is preoccupied, in this year of 1981, with the Civil War, and it will be good business to re-enact it with artificial people. Pris is now working on a Lincoln simulacrum.

by Michael Hinge

Staying over at Maury’s house, Louis meets Pris, recently released from the custody of the Federal Bureau of Mental Health, which provides free—and mandatory—treatment for people identified as mentally ill per the McHeston Act of 1975. Louis mentions that one in four Americans have served time in a Federal Mental Health Clinic. Pris was diagnosed as schizophrenic, and committed, in her third year of high school.

Louis asks her to stop her noisy activities because it’s late and he wants to go to sleep. She refuses, and says, “And don’t talk to me about going to bed or I’ll wreck your life. I’ll tell my father you propositioned me, and that’ll end Masa Associates and your career, and then you’ll wish you never saw an organ of any kind, electronic or not. So toddle on to bed, buddy, and be glad you don’t have worse troubles than not being able to sleep.” Louis thinks: “My god. . . . Beside her, the Stanton contraption is all warmth and friendliness.”

In a later encounter: “Why aren’t you married?” she asked.

“I don’t know.”

“Are you a homosexual?”

“No!”

“Did some girl you fell in love with find you too ugly?”

In addition to this finely honed nastiness, Pris is also capable of considerable depression and self-pity. After the Lincoln is completed:

“Oh, Louis—it’s all over.”

“What’s all over?”

“It’s alive. I can never touch it again. Now what’ll I do? I have no further purpose in life.”

“Christ,” I said.

“My life is empty—I might as well be dead. All I’ve done and thought has been the Lincoln.”

Louis is shaken by these encounters. He sees a psychiatrist and gives a paranoid account of events to date, threatening to kill Pris. Further: “I was not kidding when I told you I’m one of Pris’ simulacra. There used to be a Louis Rosen, but no more. Now there’s only me. And if anything happens to me, Pris and Maury have the instructional tapes to create another.” Later he reiterates, in a conversation with the Stanton: “I claim there is no Edwin M. Stanton or Louis Rosen any more. There was once, but they’re dead. We’re machines.” The Stanton acknowledges, “There may be some truth in that.”

And if you’ve missed the point about humans and simulacra, here it is from the other direction. The Stanton says he would have liked to see the World’s Fair. Louis says: “That touched me to the heart. Again I reexperienced my first impression of it: that in many ways it was more human—god help us!—than we were, than Pris or Maury or even me, Louis Rosen. Only my father stood above it in dignity.”

The characters get involved with Sam Barrows, a rich guy who is the talk of the nation, in hopes of a profitable business relationship. Barrows is selling real estate on the Moon and other extraterrestrial locations. He sensibly trashes Maury’s idea of Civil War re-enactment, but his proposal is hardly an improvement; he wants to create simulacra of ordinary folks to go live in his off-planet housing developments and make them seem homier to potential buyers. (Sounds very practical, right?)

Pris then takes up with Barrows and begins calling herself Pristine Womankind. Meanwhile, Louis is getting progressively crazier, propelled by his obsession with Pris, and eventually winds up committed to the Federal Bureau of Mental Health—and is glad. There are a few more events and revelations I won’t spoil.

So, what follows from this prolonged but foreshortened precis?

First, this is not a very good SF novel, because it doesn’t follow through on its SFnal premises and also doesn’t make a lot of sense in general. It starts with the premise that historical replicas can be convincingly manufactured, and can exercise volition and easily adapt to a world a century in their future. OK, show me. But Dick doesn’t. We actually see relatively little of the Stanton and the Lincoln over the course of the novel. Further, we’re told that these artificial people are variations on models developed by the government. For what? And where are they and what are they doing? There’s no clue about the effects of this rather monumental development, other than allowing an obscure piano company to tinker with it.

The novel’s envisioned future doesn’t add up either. We’re told the setting is the USA in 1981, but there is routine space travel and colonization of the Moon and planets. More mind-boggling, there is the Federal Bureau of Mental Health—created by statute in 1975!—under which the entire population must take mental health tests administered in schools, and those deemed mentally ill are committed to a mental health clinic. As already noted, a fourth of the population has been committed at some point. And what political or cultural crisis or revolution has not only countenanced such an authoritarian regime, but also come up with the money for such a gigantic system of confinement?

Dick also seems to have made up his own system of psychiatry. Louis is diagnosed with a mental disorder requiring commitment through the James Benjamin Proverb Test. While interpretation of proverbs is sometimes used in psychiatric diagnosis, I can’t find any indication that this Benjamin Test exists anywhere besides Dick’s imagination.

Louis is asked to interpret “A rolling stone gathers no moss.”

“ ‘Well, it means a person who’s always active and never pauses to reflect—’ No, that didn’t sound right. I tried again. ‘That means a man who is always active and keeps growing in mental and moral statute won’t grow stale.’ He was looking at me more intently, so I added by way of clarification, ‘I mean, a man who’s active and doesn’t let grass grow under his feet, he’ll get ahead in life.’

“Doctor Nisea said, ‘I see.’ And I knew that I had revealed, for the purposes of legal diagnosis, a schizophrenic thinking disorder.’”

Turns out the correct answer—which Louis says he really knew—is “A person who’s unstable will never acquire anything of value.” But if any of the other interpretations of this deeply ambiguous platitude—or acknowledgement of its ambiguity—proves one a schizophrenic, I guess I’d better turn myself in. (Cue soundtrack: “They’re Coming to Take Me Away.”)

The doctor goes on to explain that Louis has the “Magna Mater type of schizophrenia”:

“ ‘The primary form which ‘phrenia takes is the heliocentric form, the sun-worship form where the sun is deified, is seen in fact as the patient’s father. You have not experienced that. The heliocentric form is the most primitive and fits with the earliest known religion, solar worship, including the great heliocentric cult of the Roman Period, Mithraism. Also the earlier Persian solar cult, the worship of Mazda.’

“ ‘Yes,’ I said, nodding.

“ ‘Now, the Magna Mater, the form you have, was the great female deity cult of the Mediterranean at the time of the Mycenaean Civilization. Ishtar, Cybele, Attis, then later Athene herself . . . finally the Virgin Mary. What has happened to you is that your anima, that is, the embodiment of your unconscious, its archetype, has been projected outward, unto the cosmos, and there it is perceived and worshipped.’

“ ‘I see,’ I said.”

Now, nowhere is it written that an SF writer can’t invent future psychiatry, any more than future physics or sociology, or alternative history. But plopping this scheme down in the America of 12 years hence, without support or explanation of how we got there from here, is incongruous and implausible. And the nominal date of 1981 is not the issue. The novel is firmly set in the familiar USA of today or close to it, with androids, spaceships, and psychiatry based on ancient religions in effect stuck on with tape and thumb tacks.

Of course, absurdity and incongruity are far from rare in PKD’s work, but they generally appear in the context of madcap satire or grim lampoon (consider Dr. Smile, the robot psychiatrist-in-briefcase in The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, whose function is not to cure, but to drive the protagonist crazy so he can evade the draft). But that’s not what’s going on here. This novel, though it has its witty moments, presents overall as thoroughly sober and serious, assisted by Louis’s flat first-person narration.

So, if it’s not good SF, is it good anything else? Editor White said in the last issue, “It’s more of a novel of character than any previous Philip K. Dick novel, and in writing and scene construction it approaches the so-called ‘mainstream’ novel.” Pris is an appallingly memorable character, both for her conduct and for her effect on others, and her part of dialogue is finely honed. A novel that closely examined her and her effect on those around her might be quite impressive. But in a novel that starts out with android historical figures and ends up in a national coercive mental health system, with spaceships and moon colonies along the way, there’s too much distraction for Pris and her relationships to be adequately developed.

The bottom line is that the author has mixed up elements of SF and the “mainstream” novel without developing either satisfactorily or adequately integrating them.

In the last chapter, the author makes a conspicuous effort to bring the novel’s disparate elements together, and winds things up in the most quintessentially Dickian fashion imaginable. In fact, it all seems a little too pat. But wait. Remember editor White’s cryptic statement in last issue’s editorial that this serial was not cut, but was “slightly revised and expanded” for its appearance here? There’s a rumor that this last chapter was not actually written by Dick, but was added by White. True? No doubt we’ll find out . . . someday.

A readable failure. Two stars.

Moon Trash, by Ross Rocklynne

Ross Rocklynne (birth name Ross Louis Rocklin) started publishing SF in 1935 and became very prolific in the 1940s, placing more than 10 stories most years through 1946, many in the field leader Astounding Science Fiction, but most in assorted pulps. After that his production fell off, he disappeared from Astounding, and ceased publishing entirely from 1954 to 1968, when he reappeared with a burst of stories in Galaxy. He was a heavyweight by production, but seemingly a lightweight by lasting impact. Only five of his stories were picked up in the explosion of SF anthologies of the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, and to date he has published no books.

by Ralph Reese

Moon Trash is a contrived piece about young Tommy, who lives on the Moon with his cranky old stepfather Ben Fountain; his mother seems to be dead though it’s not explicit. Tommy has bought the official ideology of keeping the Moon spick and span, and Ben gets annoyed when Tommy picks up things that Ben has dropped along the way. Then Tommy finds a bit of trash that somebody dropped about a million years ago, and it leads them to a cave full of artifacts of an alien civilization, including precious gems.

Ben’s not going to tell anybody and is going to see how he can make money from this find, but in his greed he pulls a heavy statue over and it kills him. Tommy reports that Ben fell down a crater wall, returns the artifact Ben had taken to the cave, tells no one about it, and resolves he’s going to work and become a big shot on the Moon. The obvious subtext of the title is that even on the Moon there will be people who are down and out or close to it—people like Ben are the Moon trash, though young Tommy is a class act. Three stars, barely.

Merry Xmas, Post/Gute, by John Jakes

John Jakes had been contributing to Amazing and other SF magazines, mostly downmarket, since 1950, to little notice or acclaim until he devised his Conan imitation Brak the Barbarian for Fantastic. In his very short Merry Xmas, Post/Gute, an impoverished author tries to get the last remaining book publisher to read his manuscript, only to be told it is closing its book division as unprofitable. It’s as heavy-handed as it is lightweight. Two stars.

Questor, by Howard L. Myers

Howard L. Myers—better known by his very SFnal pseudonym, Verge Foray—contributes Questor, a semi-competent piece of yard goods of the sort that filled the back pages of the 1950s’ SF magazines. Protagonist Morgan is part of a raid brigade attacking Earth, without benefit of spaceships, which are passe in this far future. He’s a Komenan; Earth is dominated by the Armans; it's not clear why we should care. Morgan is special; his assignment is to pretend to be a casualty and fall to Earth; but he’s hit by a “zerburst lance” and both he and his transportation equipment are injured. He lands in a Rocky Mountain snowbank and emerges, after some recuperation, to find himself in a valley he can’t climb out of.

by Jeff Jones

But all is not lost. A talking mountain goat, named Ezzy, appears (intelligence and fingers engineered by long-ago humans), and offers to help him out. We learn just what Morgan is looking for on Earth—it’s called the Grail! Or, the goat says, “it can be called cornucopia, or Aladdin’s Lamp—or perhaps Pandora’s Box. . . . The only certain information is that it has vast power, and has been around a long time.” Morgan later adds, “We only know it appears to assure the survival and success of whatever society has it in its possession.” Can we say pure MacGuffin? And of course there is a wholly predictable revelation at the end involving the goat. Two stars for egregious contrivance.

The People of the Arrow, by P. Schuyler Miller

by Leo Morey

This month’s “Famous Amazing Classic” is P. Schuyler Miller’s The People of the Arrow, from the July 1935 Amazing, and it does not impress. Kor, the leader of a migrating prehistoric tribe (having recently dispatched his elderly predecessor), returns with a hunting party to discover that their camp has been attacked by ape-men (he can tell by their footprints). They have wreaked terrible carnage and have carried off the women they did not kill. So the hunting party pursues the ape-men and wreaks terrible carnage on them with their superior armament (see the title). Miller does make a credible attempt to suggest the workings of Kor’s mind and his appreciation of the changing landscape he traverses, but it’s all pretty badly overwritten and mainly notable as a large bucket of blood. Miller—now best known as book reviewer for Analog and its predecessor Astounding—did much better work later. Two stars.

The Columbus Problem: II, by Greg Benford and David Book

Last issue’s “Science in Science Fiction” article asked how difficult it would be to locate planets in a star system from a spaceship traveling much slower than the speed of light. This issue, they ask how difficult it would be from a spaceship traveling much faster—say, a tenth of light-speed. (The authors say flatly: “To the scientific community, . . . FTL is nonsense.”) Then they take a quick turn for several pages of exposition about how an affordable and workable sub-light spaceship could be designed. The Goldilocks option, they suggest, is that proposed by one Robert Bussard: a ramscoop (magnetic, since it would need about a 40-mile radius) to collect all the loose gas and dust floating around in space and channel it into a fusion reactor.

Sounds great! Once you solve a few technical problems, that is. And then finding planets is a breeze. They’ll all be in the same plane, as in our solar system—it’s all in the angular momentum. Approach perpendicular to that plane, and Bob’s your uncle. Then a fly-by can reveal basics of habitability—gravity, temperature, what’s in the atmosphere—but looking for existing life and habitability for terrestrials will require landing, preferably by remote probes of several degrees of capability.

This one is denser than its predecessor, but as before, clear, clearly well-informed, and aimed at the core interests of, probably, most SF readers. Four stars.

Summing Up

So, assuming one agrees with me about the serial, there’s not much of a showing here for this resurrected magazine, though it’s far too early to be making any broad judgments. Promised for next issue are (the good news) a serial by editor White, who has demonstrated his capabilities as a writer, and (the bad news) a story by Christopher Anvil! No doubt a Campbell reject. Let’s hope the promising overcomes the ominous.

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

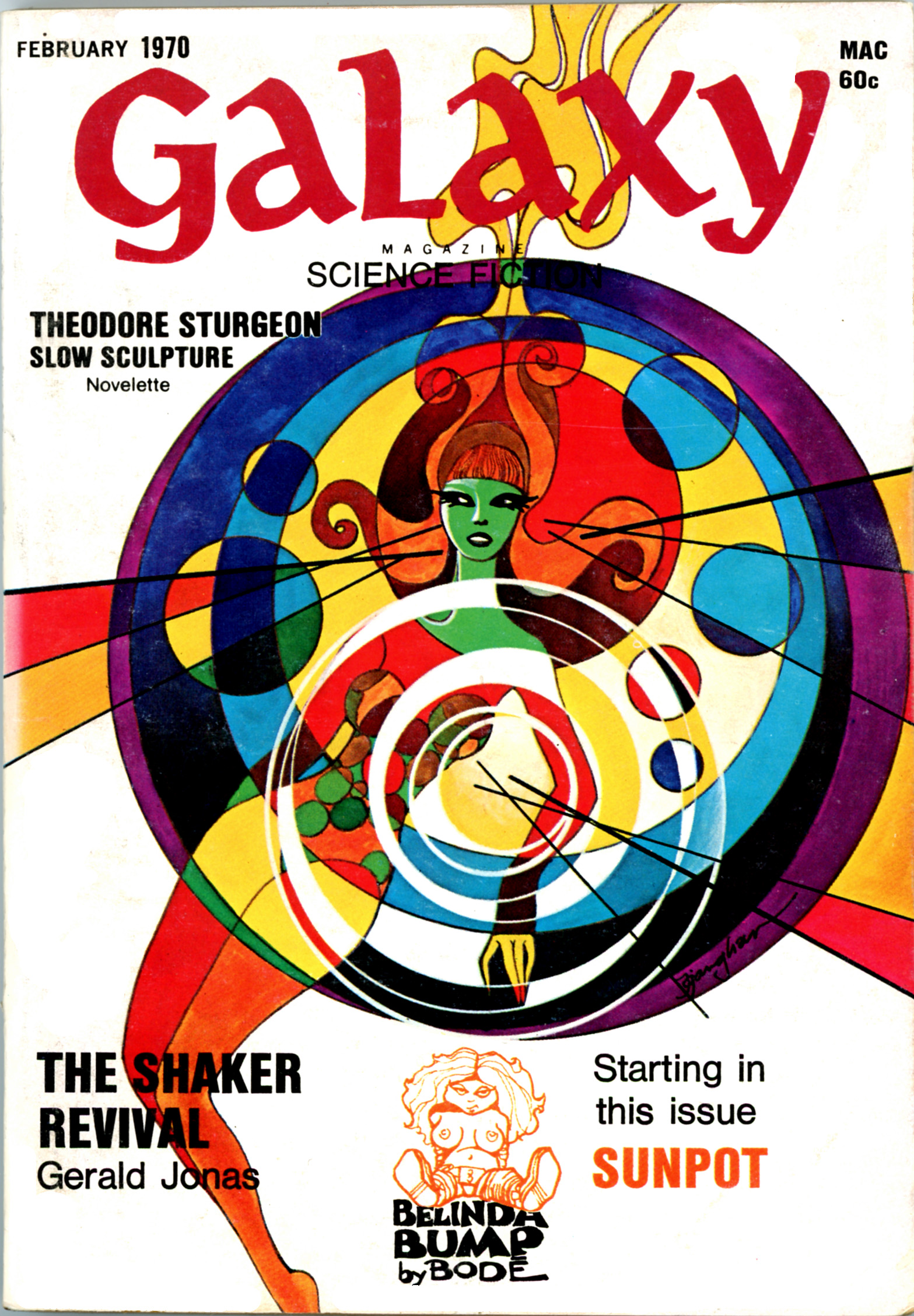

![[January 8, 1970] Slow Sculpture, Fast reading (the February 1970 <i>Galaxy Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/700108galaxycover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 2, 1970] Under Pressure (February 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IF-1970-02-Cover-500x372.jpg)

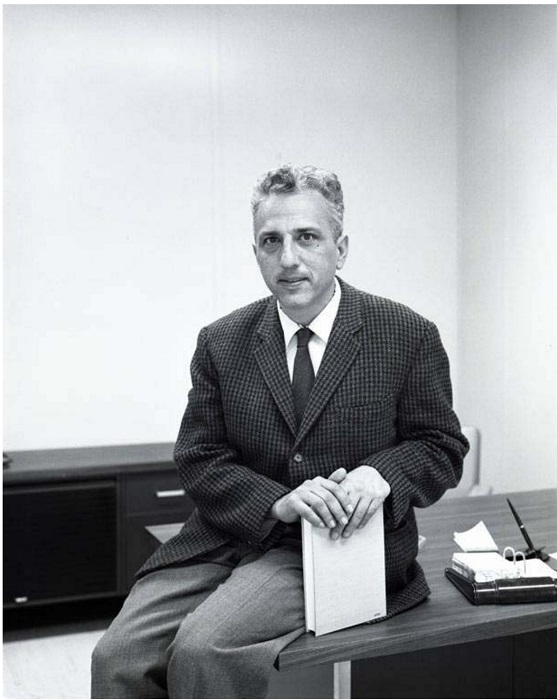

Dr. Edward D. Goldberg of the Scripps Institute of Oceanography in La Jolla, California

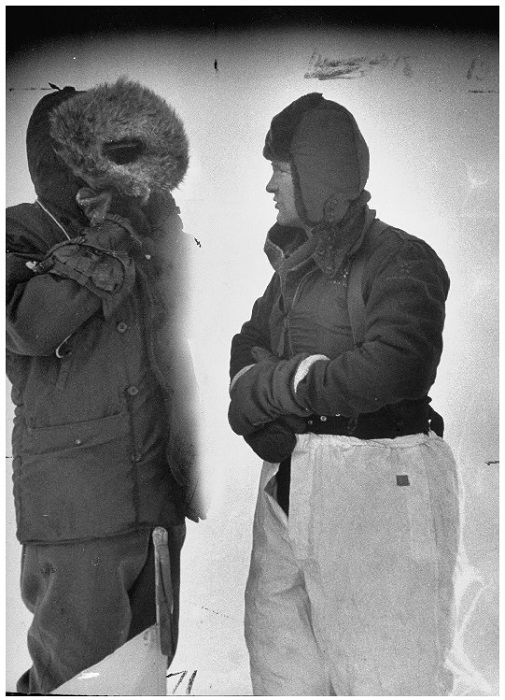

Dr. Edward D. Goldberg of the Scripps Institute of Oceanography in La Jolla, California Col. Fletcher (r.) on his ice island in 1952. This was the most recent photo of him I could find.

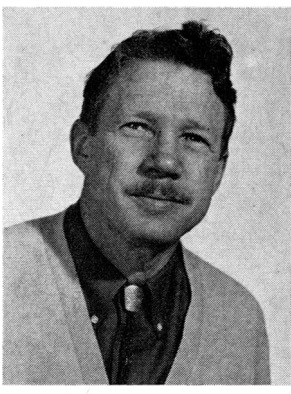

Col. Fletcher (r.) on his ice island in 1952. This was the most recent photo of him I could find. Dr. William W. Kellogg of the National Center for Atmospheric Research, in Boulder, Colorado

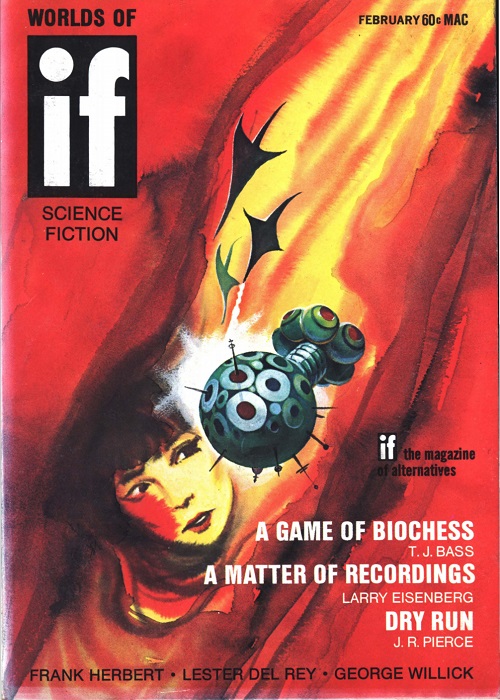

Dr. William W. Kellogg of the National Center for Atmospheric Research, in Boulder, Colorado Cover by Gaughan. Supposedly suggested by Whipping Star, but it looks more like it illustrates Pressure Vessel to me.

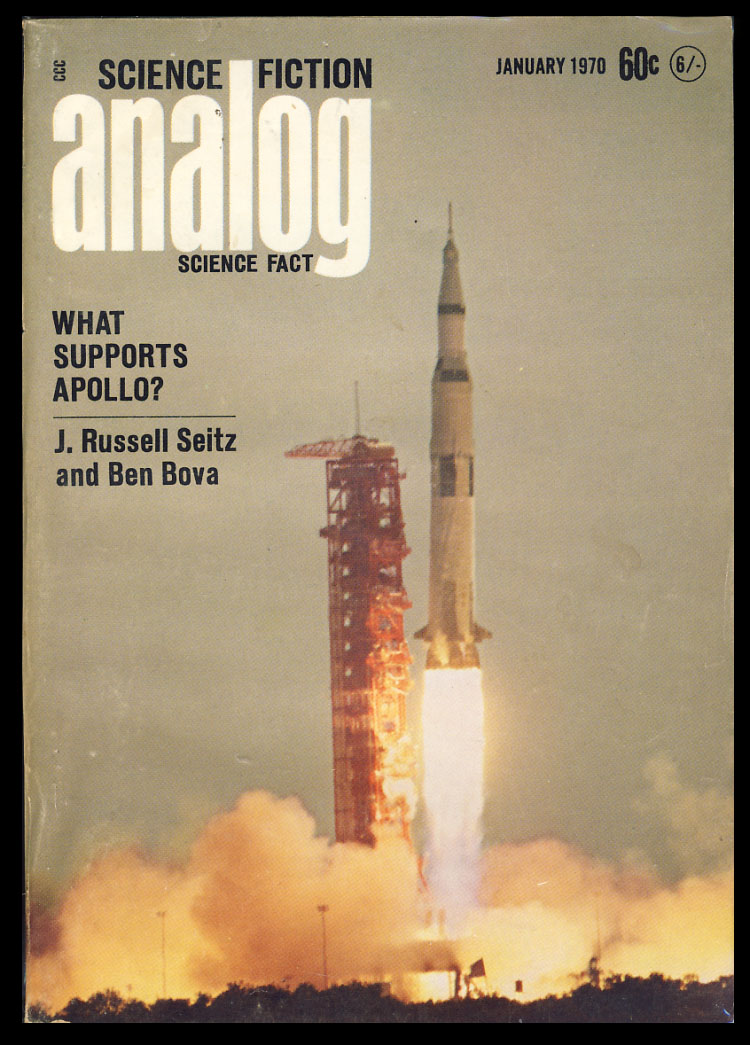

Cover by Gaughan. Supposedly suggested by Whipping Star, but it looks more like it illustrates Pressure Vessel to me.![[December 31, 1969] …for spacious skies (January 1970 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/691231cover-672x372.jpg)

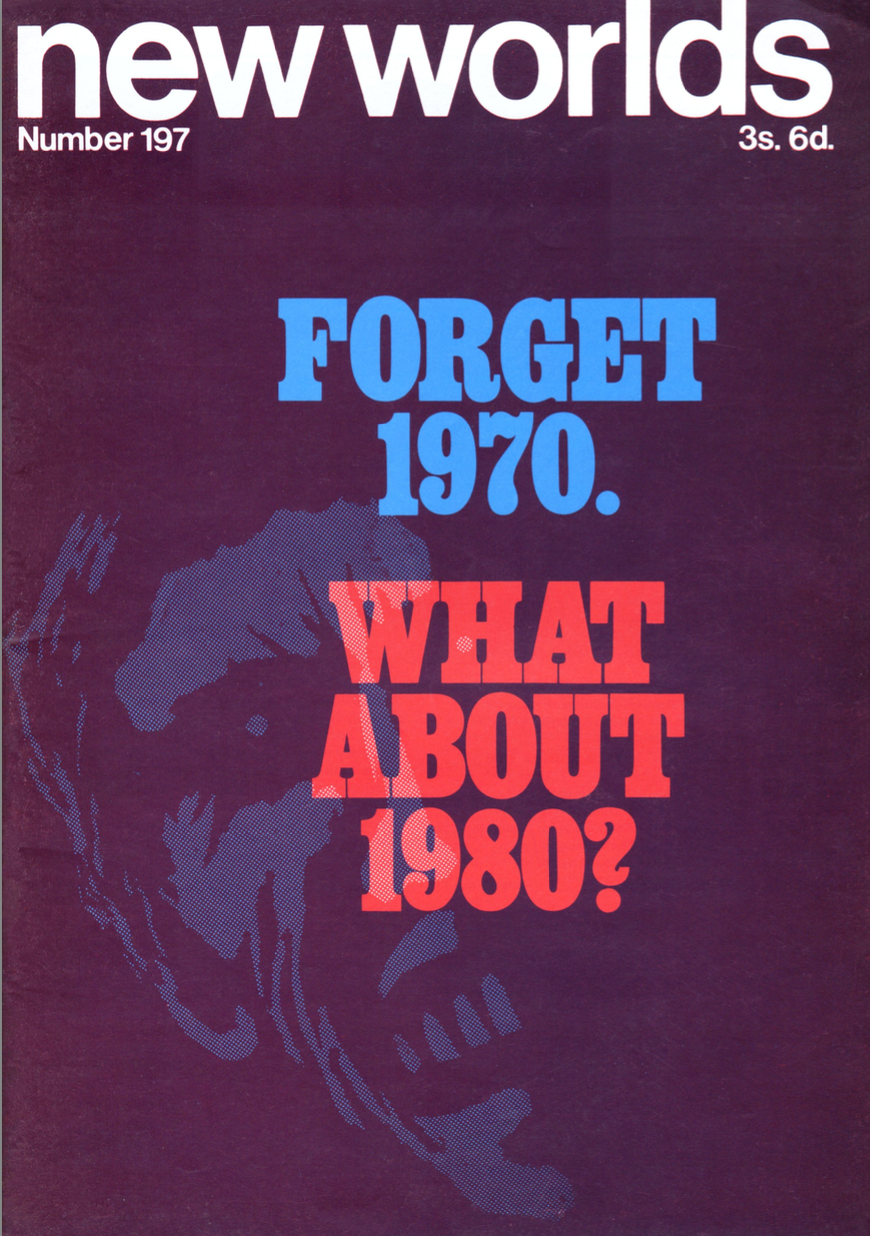

![[December 24, 1969] At Last The 1980 Show: <i>New Worlds</i>, January 1970](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/NW19701-cover-672x372.png)

None of the photos I took turned out, but here's the art for the poster.

None of the photos I took turned out, but here's the art for the poster. Cover by R. Glyn Jones.

Cover by R. Glyn Jones. Illustration by Charles Platt.

Illustration by Charles Platt. Illustration by R. Glyn Jones, who gets everywhere this issue.

Illustration by R. Glyn Jones, who gets everywhere this issue. Photo by Gabi Nasemann.

Photo by Gabi Nasemann. Design by unknown artist.

Design by unknown artist. Photo by Roy Cornwall.

Photo by Roy Cornwall. Illustration by Charles Platt.

Illustration by Charles Platt. Illustration by Pam Zoline.

Illustration by Pam Zoline. Illustration by James Cawthorn.

Illustration by James Cawthorn. Photo by Roy Cornwall.

Photo by Roy Cornwall.

![[December 20, 1969] Stars above, stars at hand (January 1970 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/691220fsfcover-406x372.jpg)

![[December 12, 1969] A More Liberal Society? (<i>Vision of Tomorrow #4</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/VOT3-349x372.png)

![[December 8, 1969] Do Better (January 1970 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/amz-0170-cover-495x372.png)

![[December 2, 1969] Communication Breakdown (January 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/IF-1970-01-Cover-478x372.jpg)

Vice President Spiro Agnew addressing the Midwest Regional Republican Committee.

Vice President Spiro Agnew addressing the Midwest Regional Republican Committee. White House Press Secretary Ron Ziegler

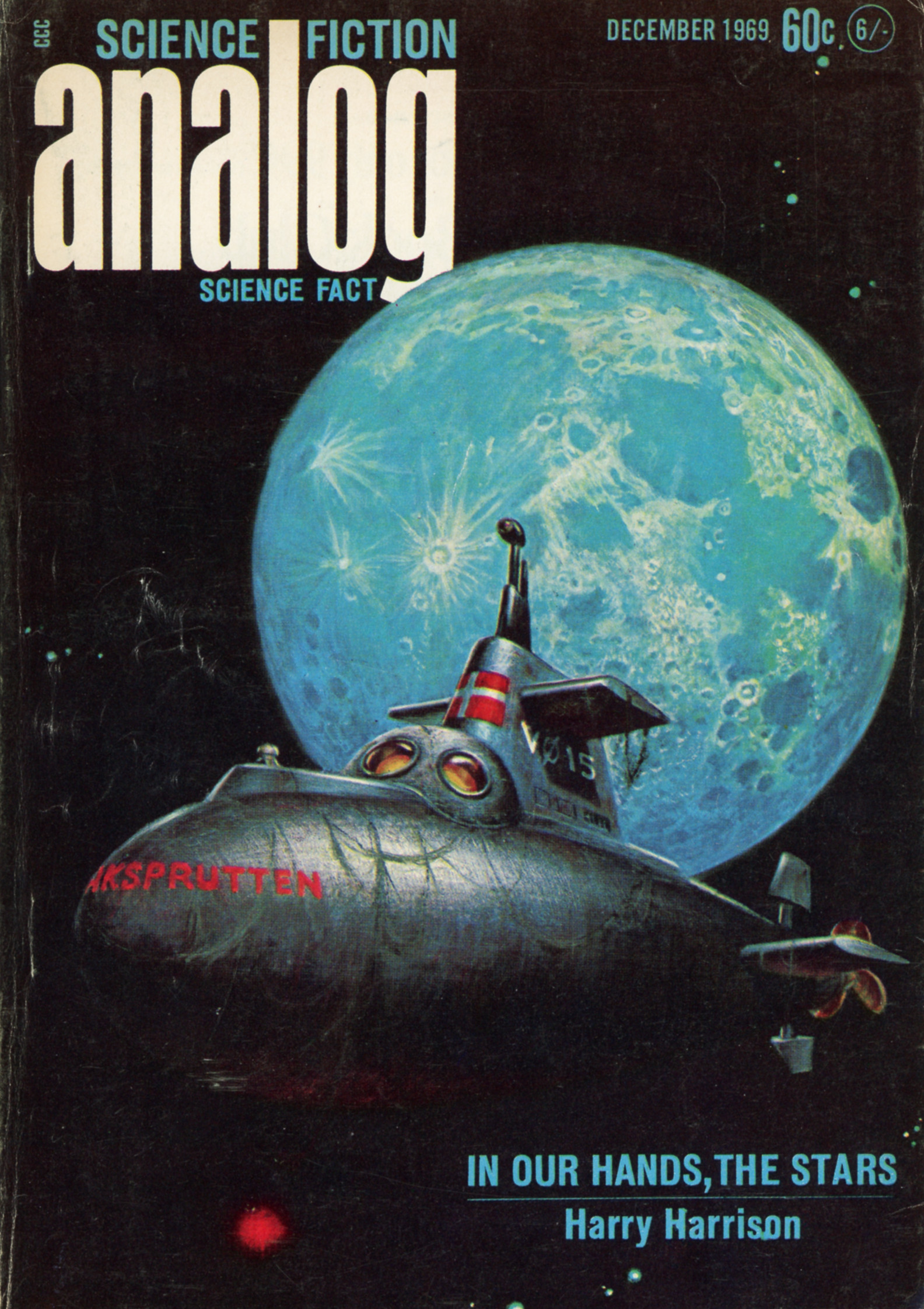

White House Press Secretary Ron Ziegler![[November 30, 1969] Capstone to a decade (December 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/691130analogcover-672x372.jpg)

![[November 20, 1969] You say you want a revolution… (December 1969 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/691120fsfcover-408x372.jpg)