[Did you meet us at Comic Con? Read this to see what we’re all about!]

by Gideon Marcus

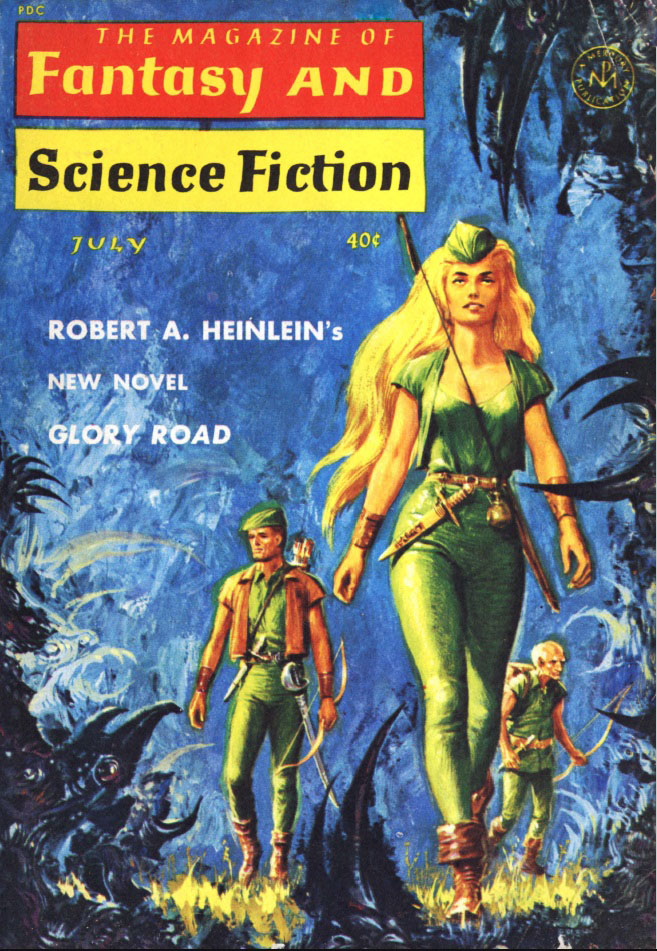

I've discussed recently how this appears to be a revival period for science fiction what with two new magazines having been launched and the paperback industry on the rise. I've also noted that, with the advent of Avram Davidson at the helm of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, the editorial course of that digest has…changed. That venerable outlet has definitely doubled down on its commitment to the esoteric and the literary.

Has Davidson determined that success relies on making his magazine as distinct from all the others as possible? Or do I have things backwards? Perhaps the profusion of new magazines is a reaction to F&SF's new tack, sticking more closely to the mainstream of our genre.

All I can tell you is that the latest edition ain't that great, though, to be fair, a lot of that is due to the absolutely awful Heinlein dross that fills half of the August 1963 Fantasy and Science Fiction. See for yourself:

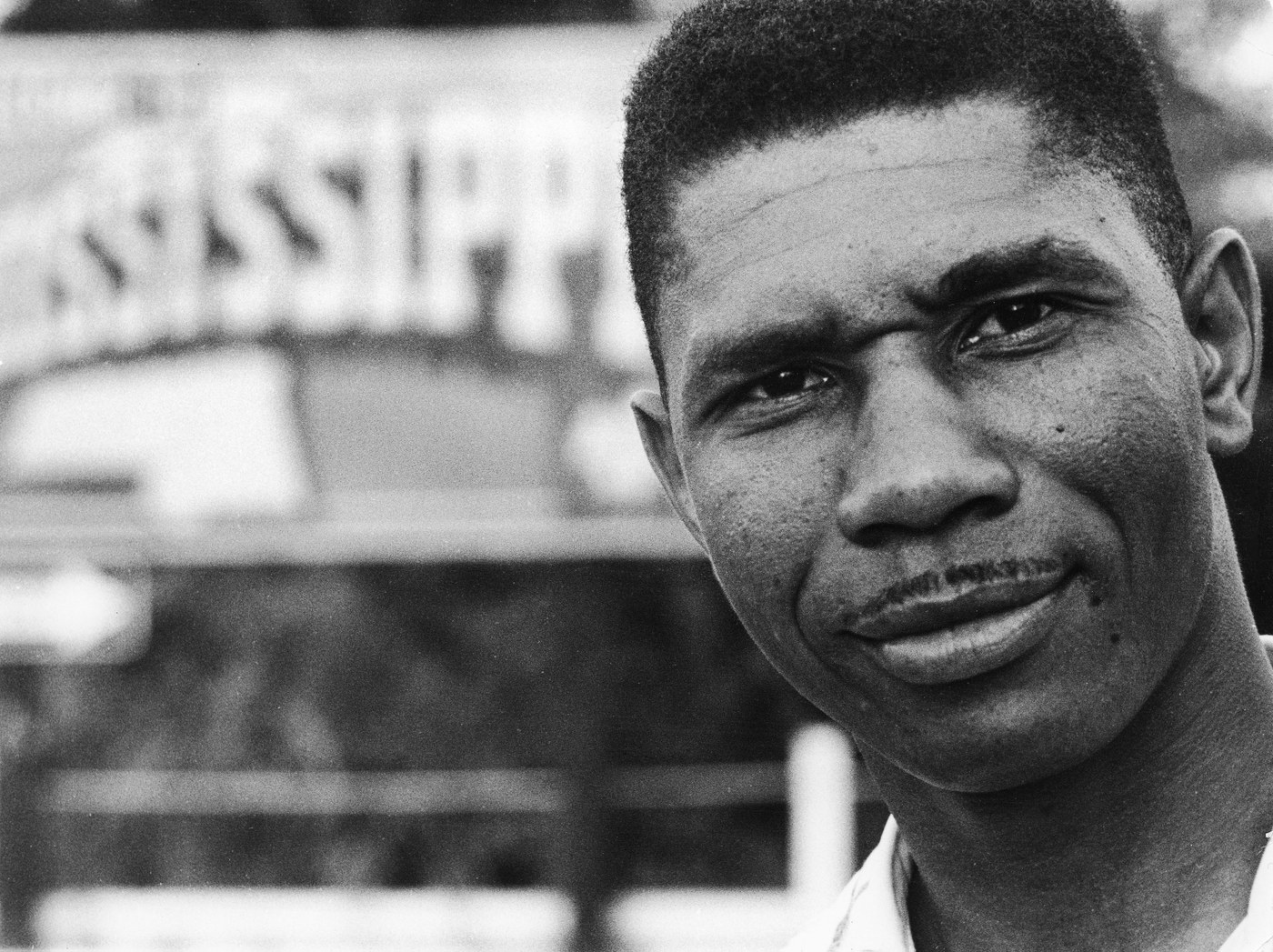

Turn Off the Sky, by Ray Nelson

Things start off strong with a tale of love and loss in a future of abundance, unemployment, and political apathy. Abelard Rosenburg, a blue-painted, black-skinned, bearded Beatnik is unswervingly committed to the cause of pacifistic anarchy, "sharing his burden" of leaflets to whomever will read them. Then he meets the beautiful Eurasian, Reva, last of the capitalists, who plies the oldest profession in a virtually moneyless society. Passion and polemics ensue.

Beautifully illustrated by EMSH, Turn Off the Sky was apparently written in 1958. Davidson held it in reserve for just the right moment. In fact, the story has that broodingly whimsical quality that marked the work of Avram Davidson at his finest – if I didn't know Ray Nelson was a real person (something of a superfan), I'd suspect this was an old work Davidson snuck in under a pseudonym. It certainly feels like something from the last decade, albeit a progressive work from that era. I liked it a lot. Four stars.

[Walter Breen of Berkeley tells me that this version is expurgated. That means they took the sex out. So much for F&SF being combined with the old Venture mag…]

Fred, by Calvin Demmon

This joke vignette is something you might enjoy telling at your next dinner party. I smiled. Four stars.

T-Formation, by Isaac Asimov

Things start to go downhill at the third-way mark. The Good Doctor has been floundering a bit lately, and his latest piece on very big numbers is both abstruse and not particularly exciting. I did appreciate his discussion of Mersenne numbers and the Fibonacci sequence, however. Three stars.

Ubi Sunt? by R. H. Reis and Kathleen P. Reis

A couple of months back, Brian Aldiss wrote a poem about how modern astronomy has killed the Mars of Burroughs. This new poem by the Reis' covers the same ground. Three stars.

Glory Road (Part 2 of 3), by Robert A. Heinlein

Last month, I covered the beginning of a promising though uneven new Heinlein serial. It began with a compelling account of one of the first veterans of our newest war (the one in Vietnam) and then declined (with some bright spots) into a fantasy novel that was a pale shadow of Poul Anderson's Three Hearts and Three Lions. It ended with our hero and his heroine, both having pledged their love for each other, tilting lances at their former benefactor, who had thrown them out for not having sex with his family.

Yes, you read that right.

How does this exciting lead-up resolve? With a disappointing, "After resolving the situation, our heroes hung out in their benefactor's steam bath and chatted." I'm not leaving anything out. That is pretty much how Part 2 begins. Then it meanders into a dialogue between the protagonists that reads as if Heinlein had a conversation with himself in the shower (before he'd entirely woken up), and someone transcribed the result.

It's bad. It's unreadable. It's the worst Heinlein I've ever read, and I'm a fan (though Podkayne of Mars and Stranger in a Strange Land sorely tested that status). Truth be told, I gave up ten pages in. Let me know if it gets better, but having skimmed some of the later pages out of morbid curiosity, it didn't look like it.

One star.

The Censors: A Sad Allegory, by T. P. Caravan

Another half-page joke piece. Not as good as the first one. Three stars.

Sweets to the Sweet, by Paul Jay Robbins

Undistinguished, middle-aged man in a loveless marriage resorts to the occult to make his mark. In the course of his studies, he discovers he's really a fantastic creature of unknown lineage, requiring just the right spell to express his true form.

This first piece by newcomer Robbins is at once half-baked and overdone, very much a freshman work, and you'll see the conclusion a mile away. Two stars.

So, once again, F&SF has oscillated into the negative end of the spectrum, and I can't help being tempted to echo the actions of a fellow reader, whose letter Davidson had the bravery to publish:

Lately, I and my friends have been somewhat disappointed with F&SF. Mr. Davidson leaves something to be desired as an editor. Therefore, I am declining your kind offer to renew my subscription to your magazine.

E. Gary Gygax, Chicago, Ill.

[P.S. Did you take our super short survey yet? There could be free beer/coffee in it for you!]