by Mark Yon

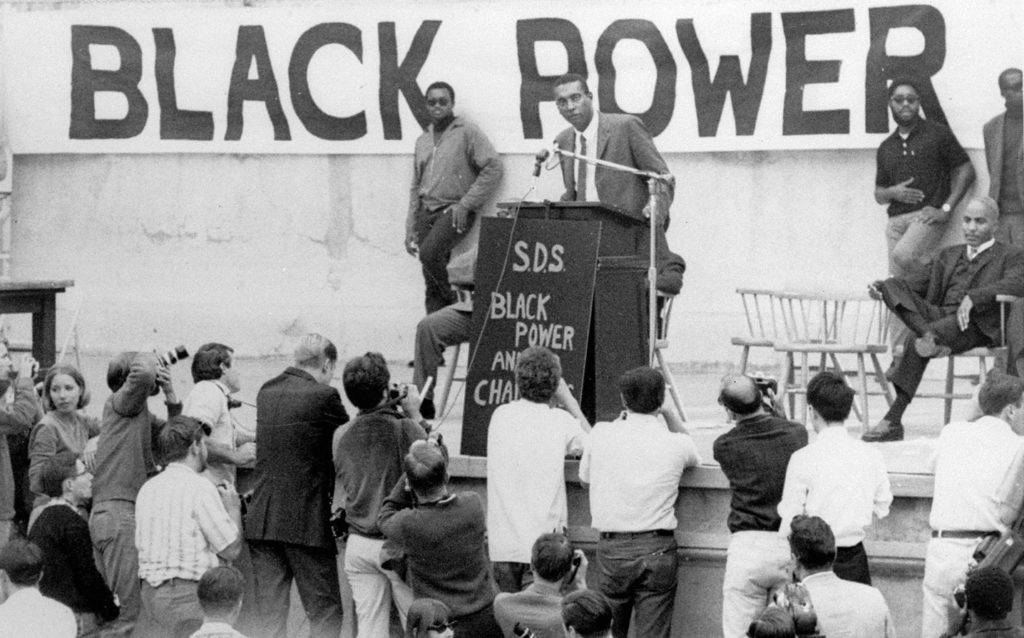

Scenes from England

Hello again!

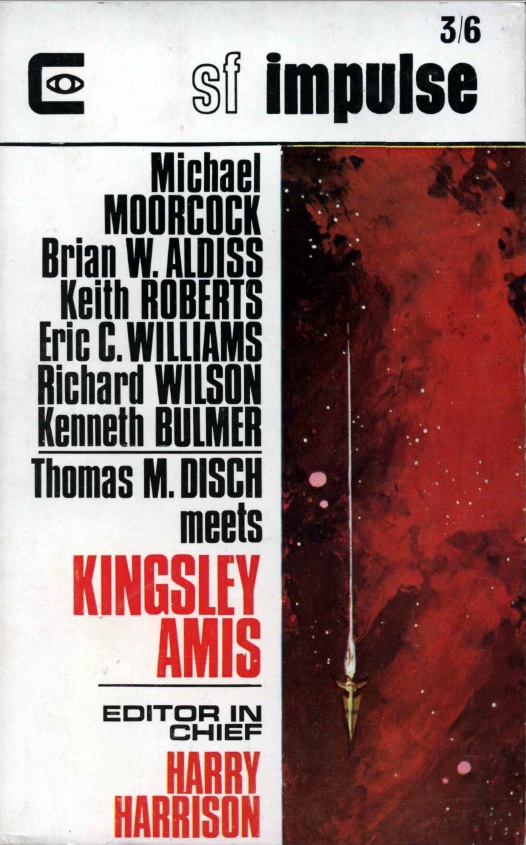

In a follow-on from last month’s comments, the rumours of falling sales on both Brit magazines seem to be holding water. This is worrying, especially when both magazines seem to be on a roll, but the one I like most is the lesser-selling of the two. New Worlds definitely presses buttons, but SF Impulse is the one I remember most.

More news as I get it.

Let’s start with New Worlds.

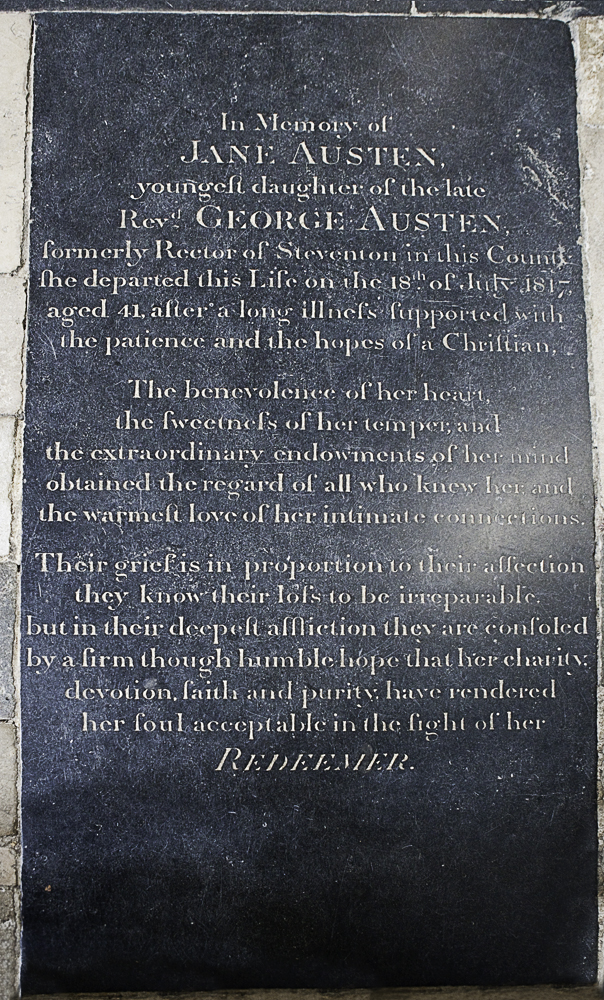

Mike Moorcock’s Editorial this month begins with the sad bit of news that Cordwainer Smith has died and then goes onto write of an aborted attempt to celebrate the centenary of H. G. Wells’ birth.

It is perhaps the last part that may be of interest to regular readers, as Mike (or is it Assistant Editor Langdon Jones?) lets slip some of the findings of the latest New Worlds reader’s survey. Unsurprisingly, the results reflect the changing state of the genre, something that regular readers will not be unaware of.

To the stories!

Echo Round His Bones (Part 1 of 2), by Thomas M Disch

Mr. Disch is everywhere in the Brit magazines at the moment. This month, for example, we have a serial novel and an interview from him over in SF Impulse (more later.) We’ve had poetry, horror stories, science fiction stories, funny stories and weird stories, all in the last six months or so. And here we have the first part of a novel, which takes up almost half of the issue.

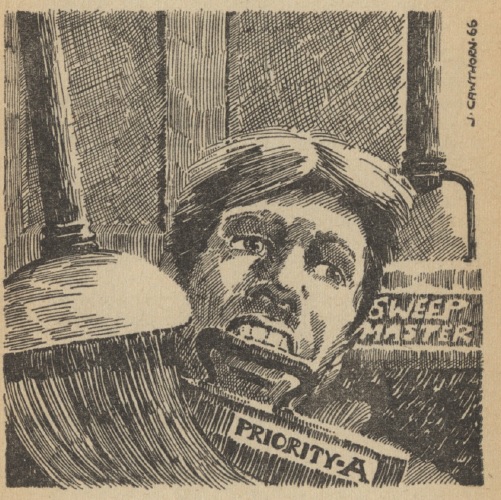

Illustration by James Cawthorn

The story is one that uses a lot of science fictional cliches but blends them up into a modern tale. In the near future scientist Panofsky has invented an instantaneous matter transmitter (Star Trek fans, take note.) Captain Nathan Hansard is a United States officer who is transferred with his platoon from Camp Jackson Pensylvania base to Camp Jackson Mars via the transmitter known as The Steel Womb. However, there is an unfortunate side effect. Hansard discovers that whilst being transferred he becomes left in limbo in some sort of in-between realm. As a result, although he is still on Earth, he is like a ghost in that he can walk through walls but cannot communicate easily with people in the ‘normal’ world.

As if that wasn’t strange enough, he also finds out that there are others stranded in this space who can interact with him normally. This is not always good, nor easy – Hansard finds himself pursued by his own soldiers, for example. Much of the middle section of this part of the story is about how Hansard comes to terms with his new environment and survives. He visits his ex-wife and son, only to find that he has become a voyeur and cannot communicate with them. He also has dreams of himself being a soldier and being involved in horrible acts in an unnamed place which looks and sounds like China.

At this point Hansard is rescued by Bridgetta, who we then discover is the wife of Panofsky, the inventor of the transmitter.

It’s a little wobbly to start with. Hansard does not come across well in the first couple of chapters — arrogant and generally unpleasant, which is not an ideal start of a character described as “a hero”. There’s also the odd major dollop of exposition in a tell-not-show kind of way. However, once the plot settles, it is exciting and memorable, shocking and interesting. The fact that there were points where I honestly couldn’t tell where this one was going makes this a good thing. 4 out of 5.

Conjugation, by Chris Priest

We’ve met Chris here before, in the May 1966 issue of Impulse with The Run. This one is different, attempting to be like Ballard’s recent work, cut up into initially disparate sections: a newspaper report, part of a speech for the President, a transcript of a videotape, an entry in an emergency-log and so on, with the verbiage kept to a minimum. Its plot is typically unclear, more an exercise in style but seems to be about an astronaut involved in an accident which seems to involve some sort of implosion. Whilst I liked the fact that the writer is trying to push the genre envelope a little, it didn’t really work for me. In the end no one does this sort of thing like Ballard. 3 out of 5.

The White Boat , by Keith Roberts

Now this was a surprise. This is a Pavane story, a series recently published in Science Fantasy, and to all intents and purposes finished. Admittedly, it was very well regarded and not just by me.

This one is a smaller vignette piece, focussed on a young teenage lobster fisherman named Becky. One night she sees a White Boat out at sea. She becomes obsessed with it and on its return ends up on it. The boat is a smuggler boat, bringing forbidden technology from France to England. Becky is returned to where she lives, to watch as the boat is shot at by soldiers of the Pope.

There’s a lot of the usual Roberts-in-more-serious-mood touches, which I liked, and even some odd vaguely sexual ones, which felt a little out of place. To be honest, the link to the world of Pavane is minimal, but there are connections if you know what to look for to connect this story to the rest.

So why is this coda piece being published in New Worlds? I’m not really sure, but with Roberts acting as Managing Editor, artist and teller of Anita stories (see later) in SF Impulse, perhaps another Roberts story there this month would have been just too much.

I liked it but did not come away quite as impressed as I was with the other stories in the series. 3 out of 5.

Lost Ground, by David Masson

How often have you heard about the weather being oppressive, moody or unsettling? In this story David makes “mood-weather” a reality in the future, where the weather does affect people’s moods, something which future generations pop pills like crazy to alleviate.

It’s good to see the return of an author who made such an impact with his first story published last year, even if more recent tales have been less impressive. However, this one I liked, perhaps because it deals with that most British of conversation topics!

Illustration by James Cawthorn

The rest of the story though does not quite live up its potential. TV reporter Roydon Greenback goes to find his wife Miriel lost in a time-storm, which leads to him being sixty-one years in the future from his original point. It doesn’t end well. Nothing especially wrong with this, it is just a bit predictable.

This one’s more like The Transfinite Choice (New Worlds, June 1966) than Traveller’s Rest (New Worlds, September 1965.) in that it has interesting ideas but not always used well. It does however introduce new words that could be scientific or just made up – chronismologists and poikilochronism, for example. Again, not his best work but far from his worst. 4 out of 5.

The Total Experience Kick, by Charles Platt

Illustration by Unknown Artist

The latest from Platt goes back to the land of The Failures (New Worlds, January 1966), which was all pop-culture and alternative lifestyle drug culture. Our hero is an industrial spy whose Total Experience machine can be used to intensify emotions through music. He is sent to infiltrate the opposition and see their latest development, with a girl involved to complicate things. It’s fun but a bit predictable, rather like rather Jerry Cornelius meets The Beatles, based around some sort of Heath Robinson contraption. I’m assuming that this story may be the inspiration for the cover picture this month. 3 out of 5.

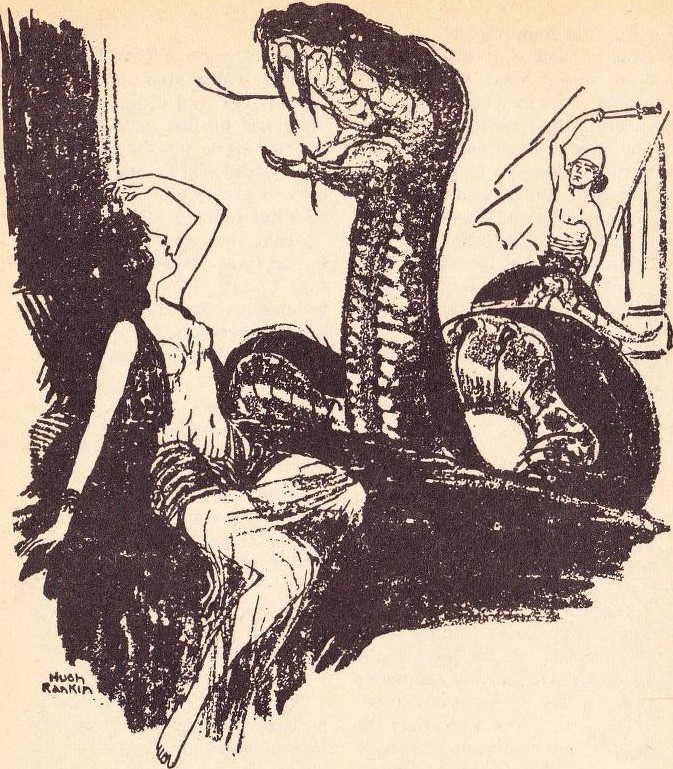

Tomorrow is a Million Years, by J. G. Ballard

Illustration by Unknown Artist

Illustration by Unknown Artist

The latest from Mr Ballard is a reprint (see Argosy, October) and also due out as part of a collection soon, I gather. Glanville and his wife Judith are able to travel time and space. They go to the fictional ship Pequod and see Ahab and his crew and talk of Glanville being The Flying Dutchman before the story turns into one of revenge. Still dark and moody but a surprisingly straightforward tale from J. G. It makes me think that this was written a while ago – it is more reminiscent of his Vermillion Sands story collection than more recent work like The Terminal Beach. 4 out of 5.

Book Reviews

This month Hilary Bailey covers a lot of books. This includes Roger Zelazny’s This immortal, Shoot at the Moon by William F. Temple, Make Room! Make Room! by Harry Harrison, Mandrake by Susan Cooper, Damon Knight’s The Other Foot, Sybil Sue Blue by Rosel George Brown, Shepheard Mead’s provocatorily-titled The Carefully Considered Rape of the World, Digits and Dastards by Frederik Pohl and The Fiery Flower by Paul I Wellman. Mike Moorcock also reviews and lists some, very briefly.

No Letters pages again this month.

Summing up New Worlds

Lots of returning authors this month. The Disch is the standout for me, although not perfect, whilst the rest are good but not great overall.

The Second Issue At Hand

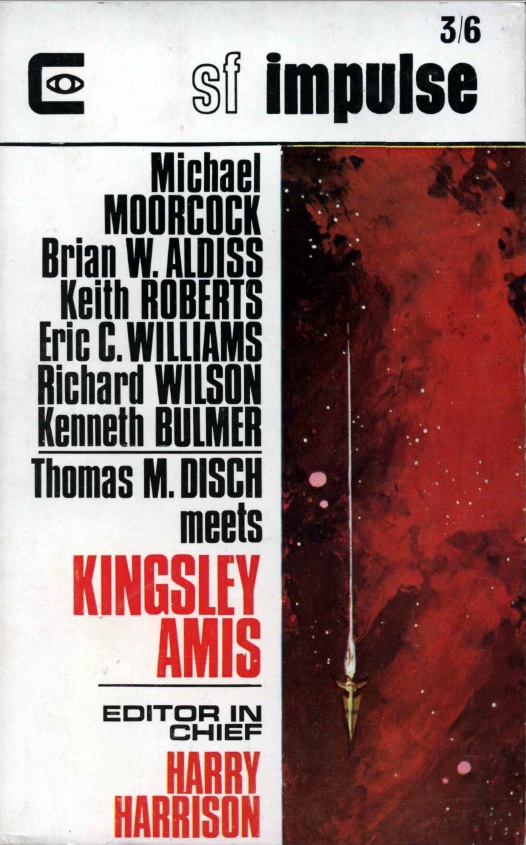

And now to SF Impulse. The cover pushes the artwork to one side this month to herald the writers and point out that there is a new Editor-in-Chief, if you didn’t know.

The Editorial is mainly Harry’s version of what happened at the Trieste Film Festival, which Francesco Blamonti reported on last month. In short, the Italians are very enthusiastic about their sf, perhaps more so than us undemonstrative Brits. Does read a little bit like an essay entitled “What me and Arthur C Clarke did on our holidays.”

Inside Out by Kenneth Bulmer and Richard Wilson

The first story this month is co-written by a duo with a long pedigree here in Britain. Ken Bulmer is a prolific author who has been published since the 1950s, but whom you might not know in the US, and Richard Wilson similarly but since the 1940s. As you might expect then this is a straightforward SF tale of the “old-school” variety.

Petty crook Duke Walsh steals a metal box full of money from an alien here on Earth in secret. The box however is not just a storage box, but a replicator, which can replicate almost anything you want. However, Duke, not realising what the box is, takes the money and throws the box away. Short yet memorable. 3 out of 5.

Three Points on the Demographic Curve by Thomas M. Disch

A story from the seemingly ever-present at the moment Mr. Disch. In the overcrowded future of 2440 (I can see why Harry likes this!), Darien Milkthirst (great name!), Investigator, is given the task of finding 56 470 kidnapped children. The kidnapper, Prosper Ashfield, appears and tells Darien that he is from the future. As the Last Man on Earth he is collecting children to repopulate the future Earth. However, the children are indolent and look upon Prosper’s robot companions as their natural superiors. Frustrated, Ashfield begins to select children from throughout history to try and redress the issue. He then goes into deep-freeze to allow the robots to continue their work.

It’s all told in the jaunty manner that the story banner describes as “wry humour”. More good stuff from Mr Disch, that reminds me a little of Robert Sheckley – not a bad thing. 4 out of 5.

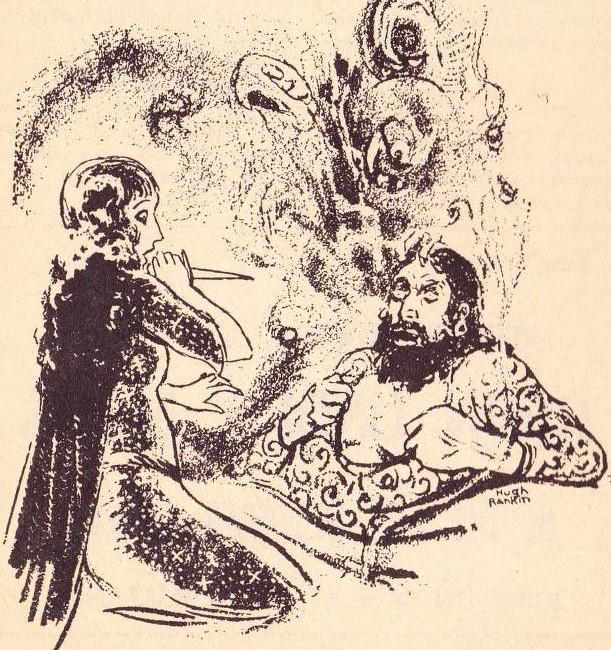

The Familiar by Keith Roberts

Illustration by Keith Roberts- the author!

Illustration by Keith Roberts- the author!

Another Anita the teenage witch story! Well, not quite, as the focus this time is upon Granny Thompson’s cat. I said that Anita’s last story felt like it was the series coming to an end and this story almost proves it. Anita is a popular character, but I think Keith is starting to scrape the bottom of the barrel with this one. Nevertheless, this is very different to Keith’s other offering in New Worlds this month. As ever with the Anita stories, The Familiar is fun and not to be taken too seriously, but not the strongest Anita story I’ve read. 3 out of 5.

Hell Revisited: An Interview with Kingsley Amis by Thomas M. Disch

Kingsley Amis is a respected author and commentator here in Britain. Harrison in his Editorial describes him as a “friendly critic”, and I would say that this is fair. His book New Maps in Hell has been seen as a critical work in recent years, extolling the virtues of sf to critics who would otherwise sneer at it.

With this in mind then, Disch’s interview is rather revelatory. Amis decries the recent writings of New Wave authors, claiming that to meet mass appeal it has lost some of its key characteristics. All of the authors hallowed in New Maps – Clarke, Pohl, Sheckley and Blish – are now criticised and of the new crowd, Messrs Aldiss, Budrys and Ballard have all disappointed. Even “run-of-the-mill science fiction is even more run-of-the-mill than it used to be”. All of this sounds a bit grumpy, yet Amis puts his points across amiably and logically. Kurt Vonnegut and Anthony Burgess come out of this well. Interesting and thought provoking.

The Real Thing by Eric C. Williams

Another returning author, last seen in Science Fantasy (whatever happened to that ?) back in August 1965. A story of what happens when Holt Mannering hires the spaceship Magpie and her crew for a day to get research for his next book. This involves getting as much realism as possible, which makes the trip rather dangerous. All written in a light-hearted manner – Heinlein it ain’t! 3 out of 5.

The Plot Sickens by Brian W. Aldiss

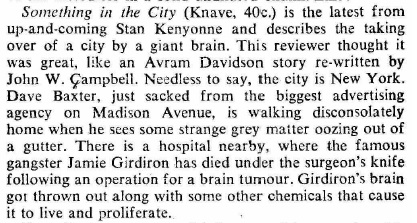

If the last story was amusing, this one is a lot more fun! In typical Aldiss manner, Brian takes the conceit begun by George Hay in his Synopsis story in Impulse 4 (June 1966) of writing reviews for imaginary science fiction novels and then spoofs it up even more. For example:

Beware the effect of an unbridled Aldiss! Makes its point whilst not savaging the genre, and a nice counterpoint to the Amis interview. Made me grin a lot. 4 out of 5.

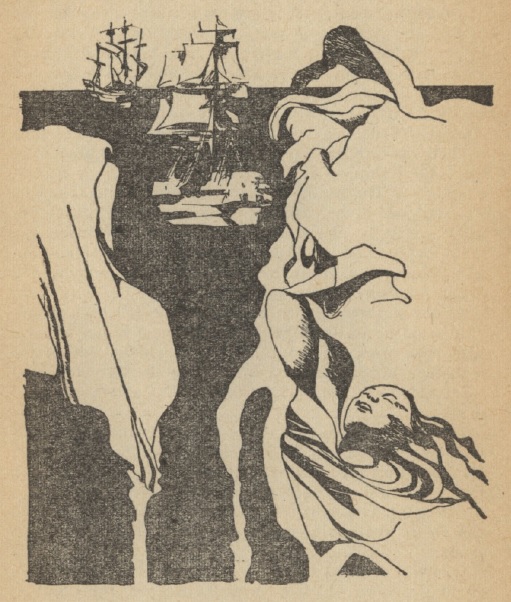

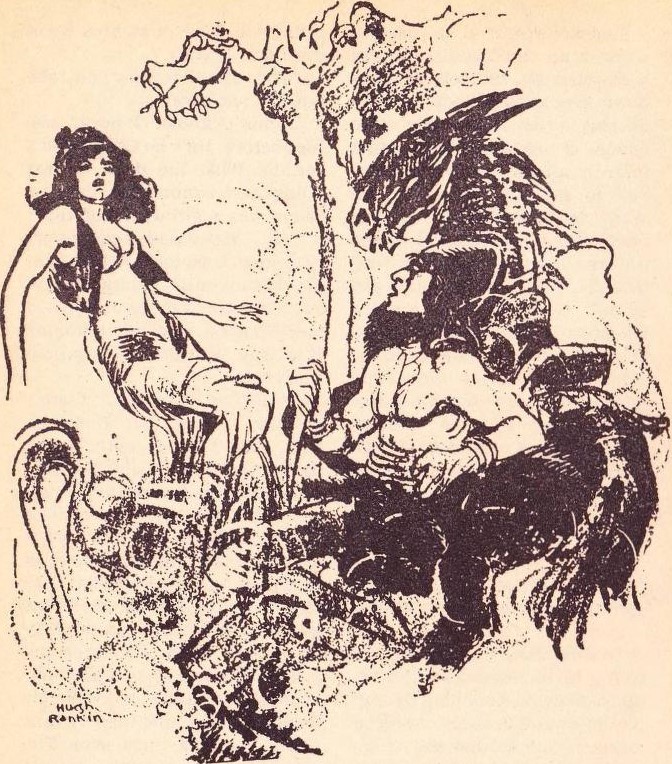

The Ice Schooner (part 2 of 3) by Michael Moorcock

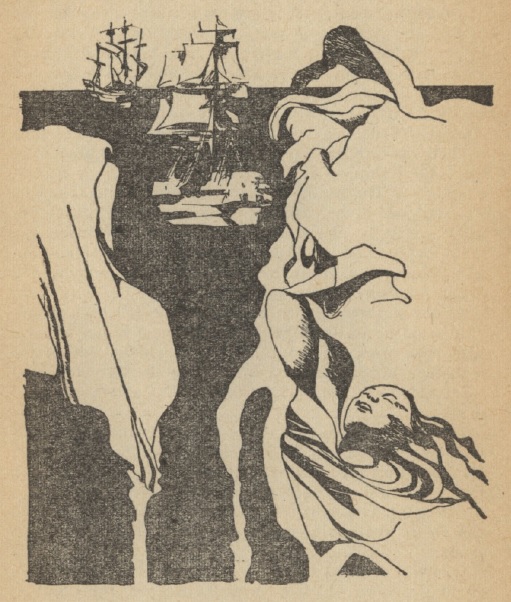

Illustration by James Cawthorn

Illustration by James Cawthorn

The first part of this story I described last month as a “post-apocalyptic Norse fantasy” introduced us to Konrad Arflane in a future Earth covered in ice. There a man Konrad rescued, Pyotr Rorsefne of Friesgalt, had said that he would like Konrad to take his ship, the Ice Maiden, and sail to the North to find the legendary New York and there the mystical Ice Mother.

The second part this month deals with the exciting but gruesome hunting of whales, and is straight out of Moby Dick. Before the journey North, Konrad has agreed to take Pyotr’s daughter Ulrica (who Konrad fancies), her arrogant husband Janek Ulsenn, and Ulrica’s cousin Manfred whale hunting, along with the legendary harpoonist Long Lance Urquart.

However, the crew of the vessel are inexperienced in whale hunting and the ship is destroyed. Manfred rescues Ulrica but Manfred receives a broken arm and Janek’s legs are broken. Arflane finds himself more and more attracted to Ulrica. Despite her being married and Konrad being warned off by both Janek and Manfred they begin an affair.

The group return to find Pyotr has died. There is a funeral. The will splits the estate between Ulrica and Manfred, with Konrad receiving the command of the Ice Spirit. If he takes on the journey to find New York, the ship and any cargo become his. It is a further condition that Ulrica and Manfred go with Arflane on this quest. Urquart goes too.

With the journey begun, the relationships between the group are strained. After Ulrica’s initial enthusiasm, she now acts coolly towards Konrad. In return, Arflame is moody as a result of Ulrica’s rebuttal. Such taciturn emotions to those around him lead the crew to begin to rumour that Konrad brings a curse with him. There are enormous difficulties faced on their journey, and the story ends as the ship encounters an ice break.

So, lots of excitement. The pace of the first part is maintained this time around. The whale hunt is particularly gruesome, although that is to be expected. Generally, this second part is nearly as good as the first, although there is a dreadfully done sex scene and an utterly convenient plot point that takes the story down a notch. At one point, it all becomes rather like a science fiction version of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, which may be intentional.

Despite this, the story is intriguing and I still like the setting. 3 out of 5.

The Voice of the CWACC by Harry Harrison

Although this is the first time the CWACC have appeared here, there have been previous stories in this series (last seen in the June 1966 issue of Analog – traveller Marcus really didn't like it.) Personally, I am always a little dubious of editors publishing their own work in their magazine – it either displays a great deal of confidence in their own worth or conveniently fills up a gap, neither of which usually bode well. I’m not quite sure which this shows!

It’s a slight tale, meant to be amusing, of scientists (the CWACC) with a new invention – an aircraft recognition system to be used for ground defence. Because of the “highly secret, unpatented, incredibly artful components” it has, it is very successful. The new twist is that the machine is worked internally by a rat – take that, Daniel Keyes! Not bad – energetically silly and fairly forgettable. And no, I still don't know what CWACC stands for! 3 out of 5.

No Letters to the Editor this month.

Summing up SF Impulse

I like the Moorcock, even if it is not quite as good as the part last month. Disch impresses (again) and both the Anita story and Aldiss’s story made me laugh – not easy to do.

Summing up overall

New Worlds is a solid issue from regular writers. SF Impulse impresses more with its stories. Disch or Moorcock? Aldiss or Harrison? Keith Roberts or… Keith Roberts? Hmm. Both issues are good, but I’m going with the SF Impulse (again) this month.

Someone say "Christmas?" All the compliments of the season to you.

Until the next (forward, 1967!)…

![[December 20, 1966] Above and beyond (January 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i> and a space roundup)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661220cover-656x372.jpg)

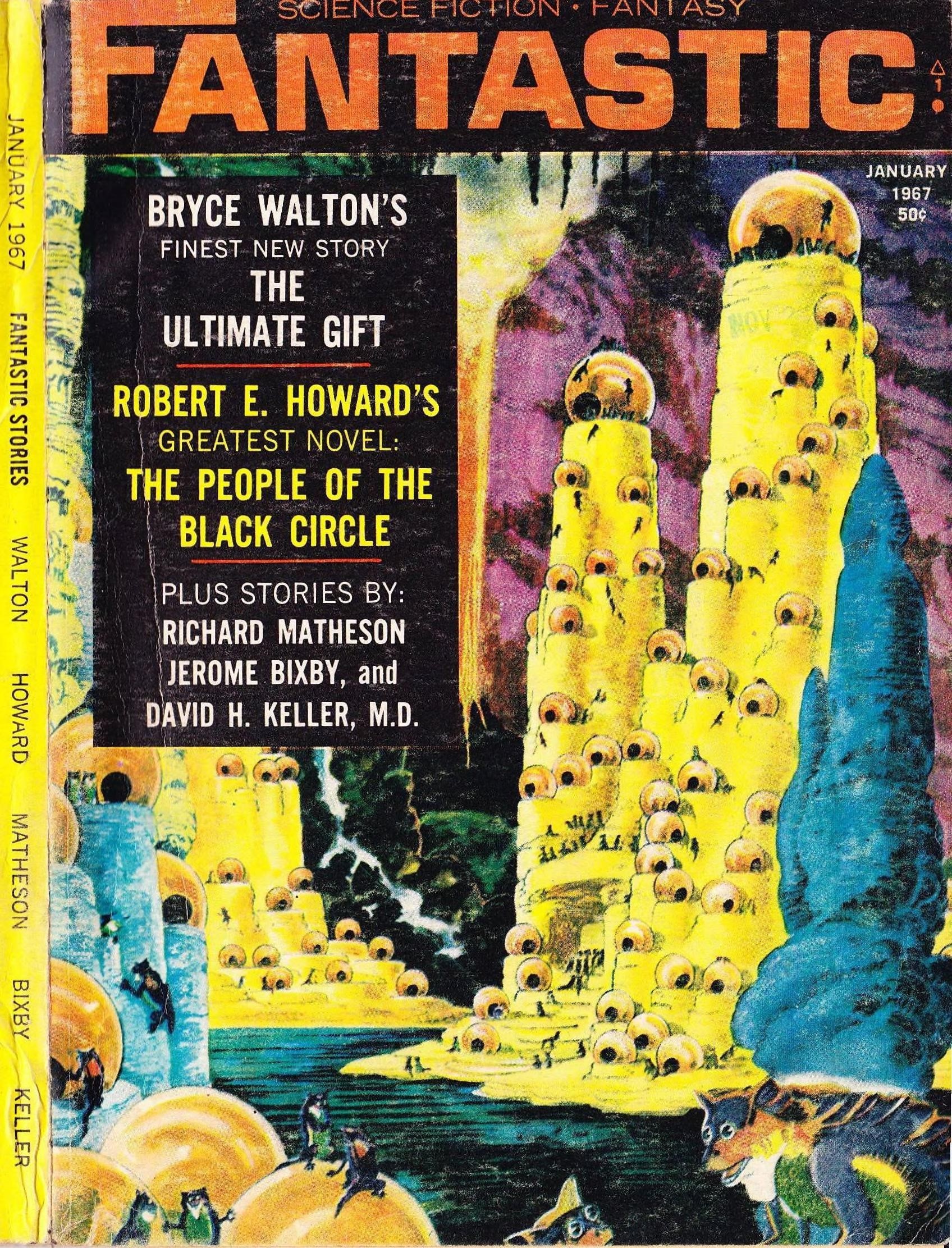

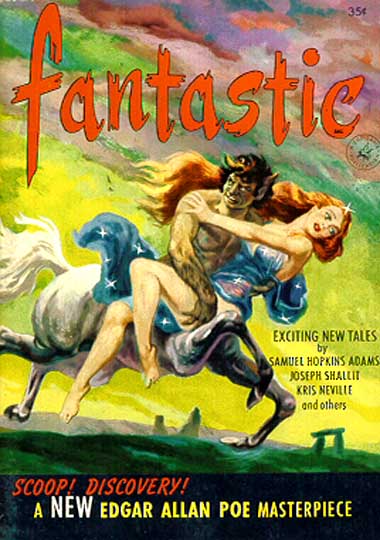

![[December 8, 1966] Flesh and Blood (January 1967 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Fantastic_v16n03_1967-01_0001-4-672x372.jpg)

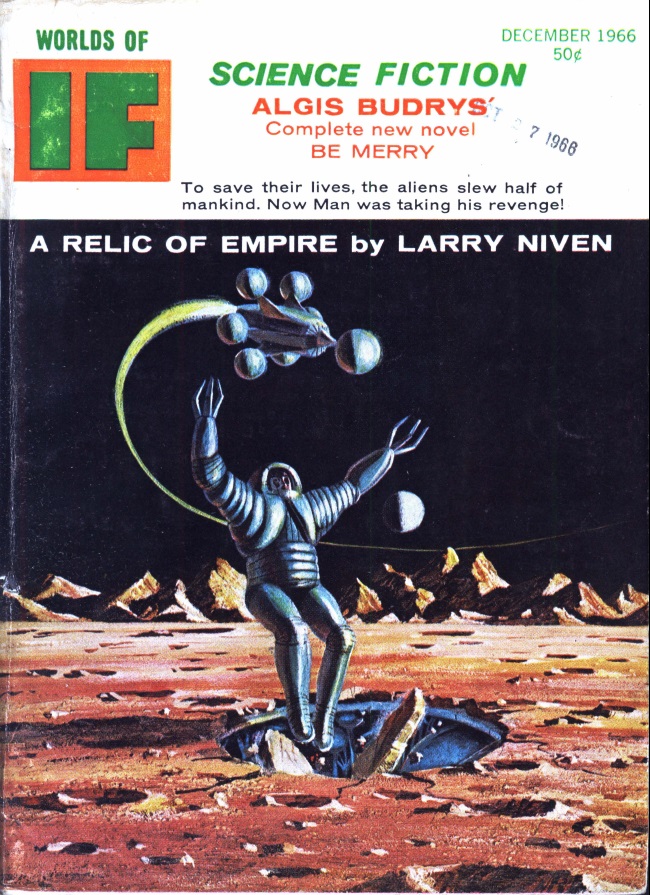

![[December 2, 1966] Mixed Bags (January 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/IF-1966-12-Cover-665x372.jpg)

![[November 30, 1966] Marking time (December 1966 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/661130cover-672x372.jpg)

![[November 26, 1966] White Boats, Whales and Disch, <i>New Worlds</i> and <i>SF Impulse</i>, December 1966](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/New-Worlds-SF-Impulse-Dec-1966-672x372.jpg)

Illustration by Unknown Artist

Illustration by Unknown Artist

Illustration by Keith Roberts- the author!

Illustration by Keith Roberts- the author!

Illustration by James Cawthorn

Illustration by James Cawthorn

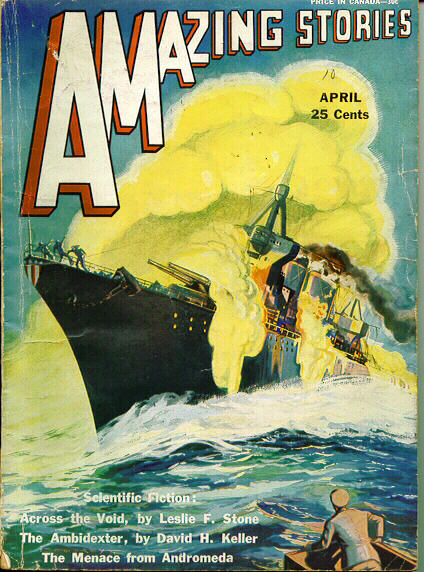

![[November 24, 1966] Middling (December 1966 <i>Amazing</i>)</big></b>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/amz-1266-cover-503x372.png)

![[November 22, 1966] Ha ha. Very funny. (December 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/661122cover-661x372.jpg)

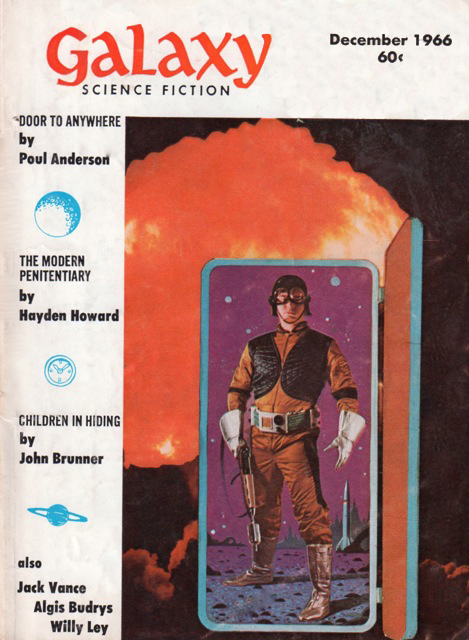

![[November 12, 1966] A Family Tradition (December 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/661112cover-469x372.jpg)

![[November 6, 1966] Starting Over (December 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/IF-1966-11-Cover-650x372.jpg)

![[October 31, 1966] Respite from the horror (November 1966 <i>Analog Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/661031cover-355x372.jpg)