By Mx Kris Vyas-Myall

As I am writing this, voting in the UK General Election is taking place. However, we will have to wait until tomorrow for the results. As such, I want to address one of the biggest perpetual issues in Britain, the housing crisis.

It has become a kind of a dark joke over the last 50 years. At election time, every party leader will say how much they feel for the plight of the homeless and pledge to end the crisis. Then, as soon as voting is over, they will go back to ignoring the issue. Therefore, I feel, it is worth listing off the endemic problems causing this.

For a start, there is the obvious matter of money and organization. The UK spends a smaller share of GDP than the rest of Western Europe on housing and leaves decisions in the hands of local councils, which have a patchwork of plans. On top of that, housing building largely relies on the private sector who are more interested in high-priced luxury developments than on those for the poorest families.

Ronan Point, post-disaster

With this combination of political short-terminism, lack of investment and reliance on the private sector, it has led to a lot of poor-quality housing stock. An infamous example was the Ronan Point Disaster, where a gas explosion collapsed the corner of a tower block.

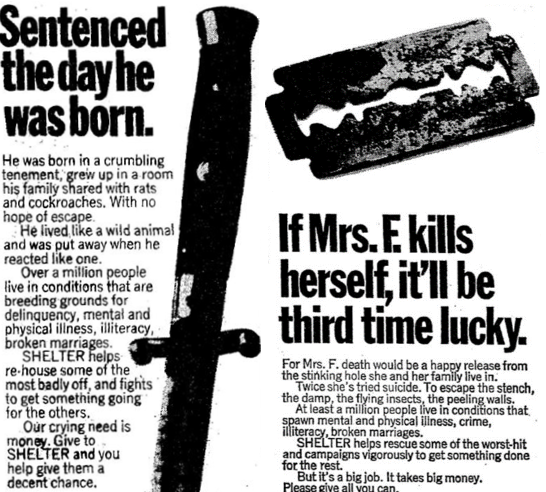

Some of Shelter’s recent advertisements

With this lack of a political solution, it is unsurprising that several groups in the voluntary sector have been trying to fill the gap. The biggest of these is Shelter and, whilst all major parties praise their work, they seem to be getting sick of the situation. They are now withholding funds from local authorities that don’t help the poorest in their communities and running advertisements blaming the current biggest social ills on the housing crisis.

There are also other groups taking more direct action. Running in the election in London is a loose party grouping called “Homes Before Roads”, opposing the plans to try to deal with London’s congestion by building a series of ring roads through current residential districts. In a different way there is also the Squatters’ Movement, who are taking control of empty housing stock and trying to get official recognition for their use by those who cannot afford to go anywhere else.

However, I am not hopeful of even direct action resulting in a solution. Whether Wilson or Heath are Prime Minister next week, I suspect the situation will still be much the same in the mid-70s: homelessness and poor-quality housing are endemic; the political parties say what a scandal this is; make vague promises at a solution; promptly ignore it again.

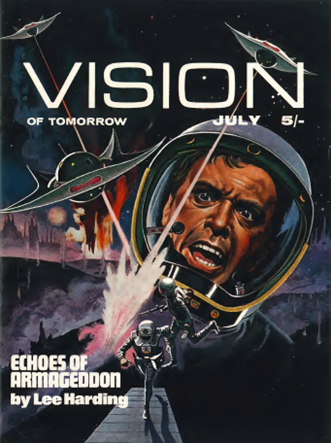

I am also getting a sense of déjà vu from the latest issue of Vision of Tomorrow, with an expansion of articles on the history of SF and the writers retreading old ground:

Vision of Tomorrow #10

Cover by Stanley Pitt

Continue reading [June 18th, 1970] A Case of Déjà Vu (Vision of Tomorrow #10)

![[June 18th, 1970] A Case of Déjà Vu (<i>Vision of Tomorrow #10</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Vision-of-Tomorrow-10-Cover-331x372.png)

![[June 12, 1970] Something Good! and Nothing Terrible (July 1970 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/amz-0770-cover-672x372.png)

![[June 10, 1970] I will fear <i>I Will Fear No Evil</i> (July 1970 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700610galaxycover-435x372.jpg)

![[June 4, 1970] Something old, something new (July-August 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/IF-1970-07-Cover-472x372.jpg)

La Balsa puts to sea.

La Balsa puts to sea. The Ra II under way. Note the tether keeping the stern high.

The Ra II under way. Note the tether keeping the stern high. Suggested by “Time Piece”. Art by Gaughan

Suggested by “Time Piece”. Art by Gaughan![[May 31, 1970] A Compulsion to read (June 1970 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/700531analogcover-672x372.jpg)

![[May 22, 1970] Back From The Dead (Summer 1970 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/COVERSMALL-1-672x372.jpg)

![[May 18th, 1970] Rematch (<i>Vision of Tomorrow #9</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Vis1.png)

![[May 12, 1970] War and Peace (June 1970 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/COVERSMALL-672x372.jpg)

![[May 10, 1970] Fever Pitch (<i>New Writings in S-F 17</i> & <i>Vortex</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Vort-Title-554x372.png)