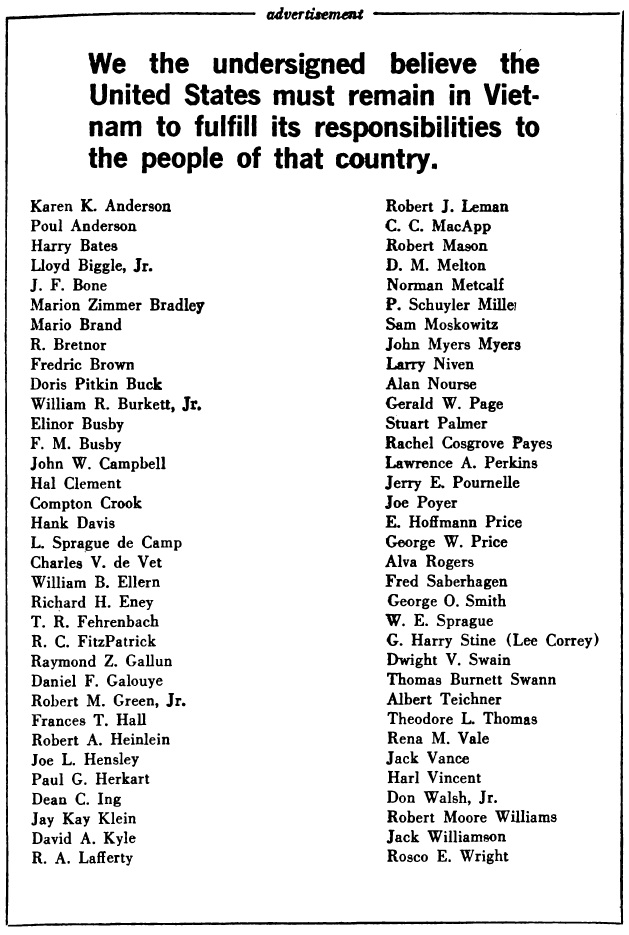

by Gideon Marcus

There's no sun up in the sky

Out in the vastness of space, a constellation of man-made moons keeps watch on the Earth below. Unlike their brethren, the military sentinels that look out for rocket plumes and atomic blasts, these benign probes monitor the planet's weather with a vantage and a vigilance that would make a 19th Century meteorologist green with envy.

In addition to the wealth of daily data we get from TIROS, ESSA, and Nimbus, the West is now getting aid from an unlikely, but no less welcome, source: behind the Iron Curtain.

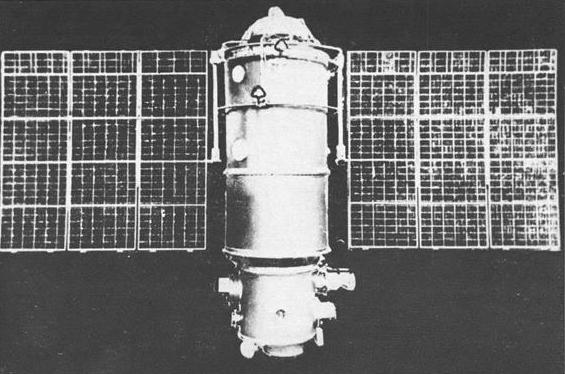

Two years ago, the Soviets rebuffed the idea of exchanging weather satellite imagery. "No need," was what they said; "no sats," was probably the real story. For in August of 1966, all of a sudden, the USSR activated the "Cold Line" link between Moscow and Washington for the exchange of meteorological data. This action coincided with the recent launch of Cosmos 122, revealed to be a weather satellite.

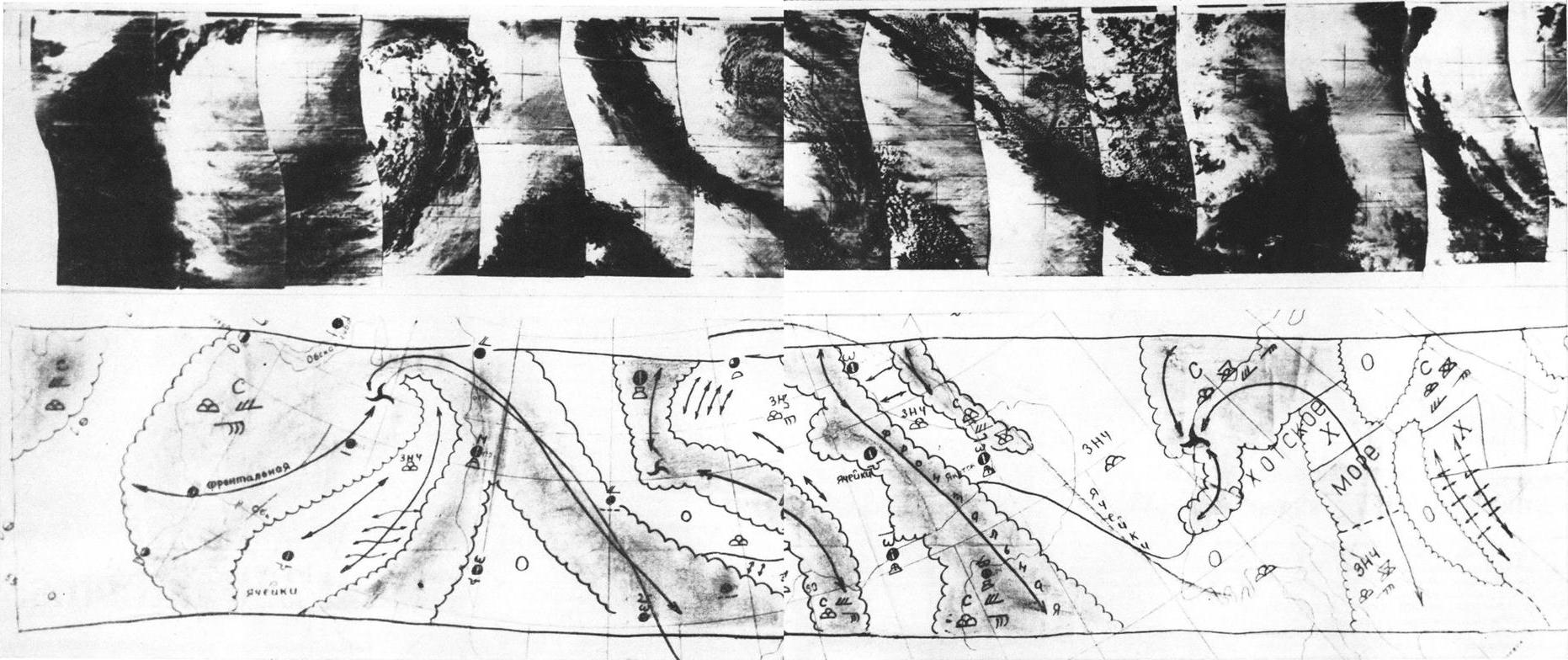

This constituted a late start in the weather race–after all, TIROS had been broadcasting since 1960. Nevertheless, better late than never. Unfortunately, the Soviets first sent only basic weather charts with limited cloud analysis. Not much good without the raw picture data. When we finally got the pictures, starting September 11, 1966, the quality was lousy–the communications link is just too long and lossy. Our ESSA photos probably didn't look any better to them.

By March 1967, however, the lines had been improved, and Kosmos 122 was returning photos with excellent clarity.

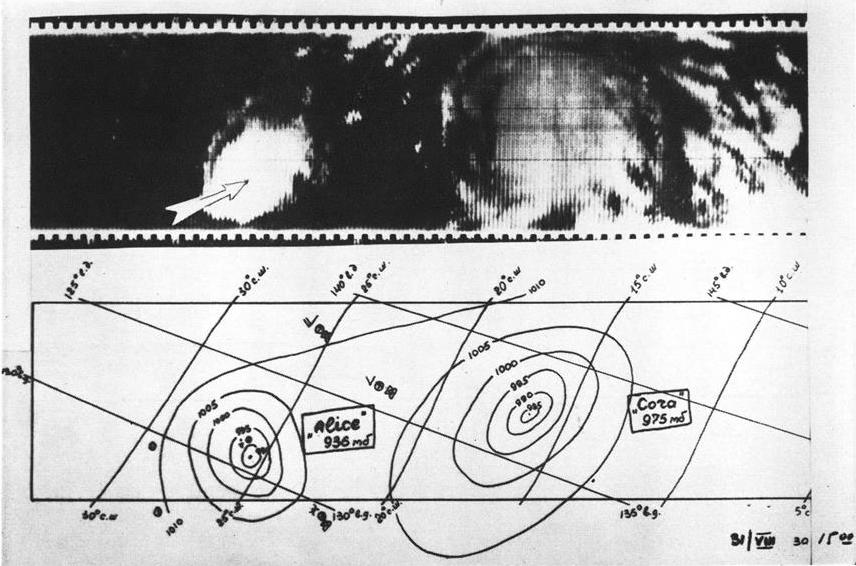

We also got infrared data. The resolution was much worse, but the Soviets maintained they did first discover a pair of typhoons bearing down on Japan.

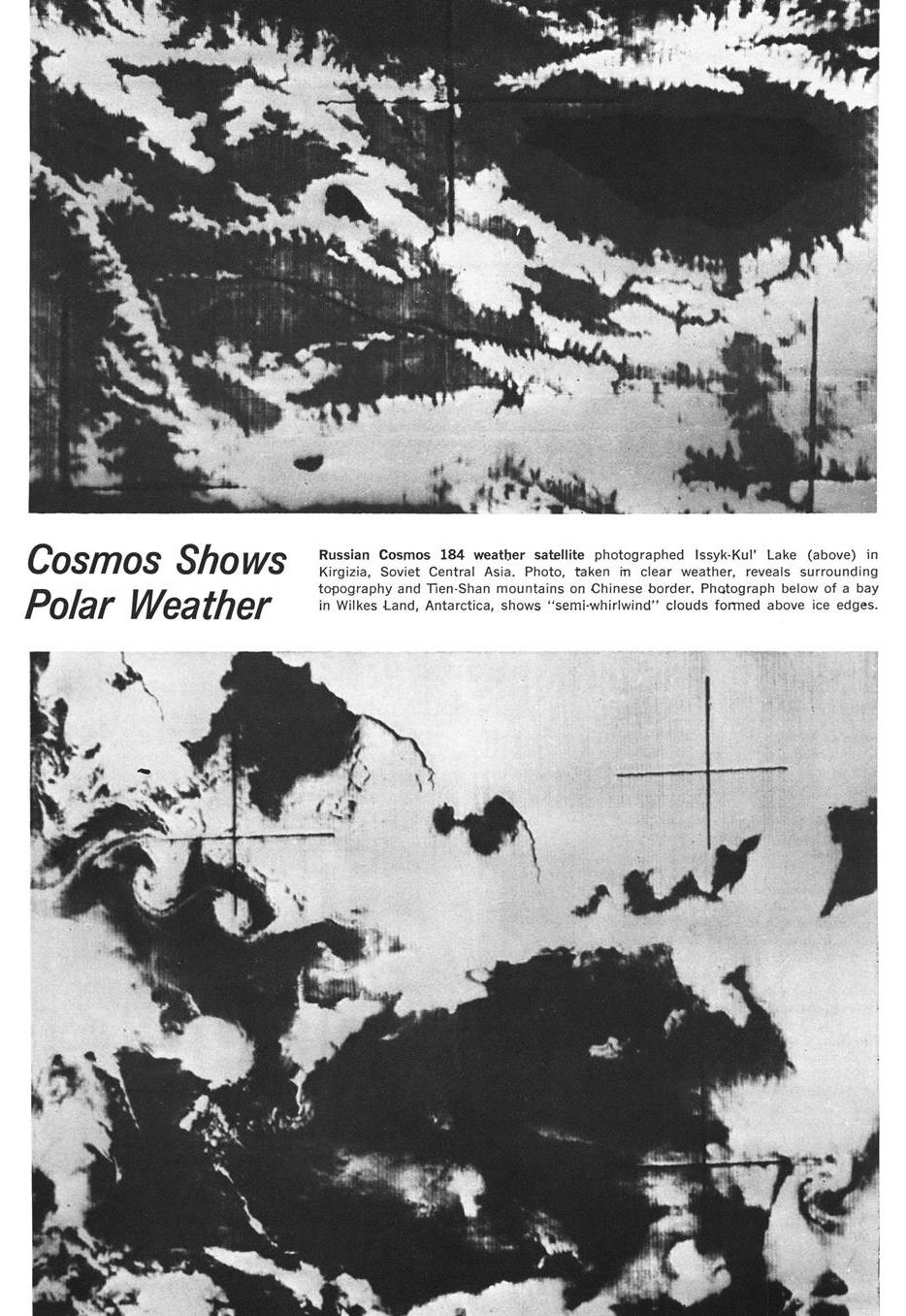

Since then, the USSR has orbited at least two more weather satellites, Kosmos 144 and Kosmos 184, both returning the same useful data, often from different orbital perspectives than we can easily reach. For instance, the Soviet pictures offer particularly good views of the poles and northern Eurasia.

It's a little thing, perhaps, this trading of weather data between the superpowers. But anything that promotes peaceful exchange and keeps the connections between East and West ready and friendly is something to appreciate. Sometimes the Space Race is more of a torch relay!

Raining all the time

by Kelly Freas

In sharp contrast, Analog remains an island unto itself, and like all inbred families, often produces challenged offspring. Such is the case with the March 1968 issue, which ranges from middlin' to awful.

The Alien Rulers, by Piers Anthony

by Kelly Freas

We start with the awful.

Fifteen years ago, the blue-skinned Kaozo engaged our space fleet, destroyed it utterly, and became the benevolent masters of Earth. They created a working socialist society, implementing tremendous public works projects, and humanity proved remarkably complacent under their rule. Nevertheless, a revolution of sorts has been hatched, and Richard Henrys is tasked with the stickiest assignment–assassinate the Kazo leader, Bitool.

Henrys is quickly captured, but instead of facing execution, Bitool offers him a deal: protect Seren, the first female Kazo on Earth, during the next three days of the revolution, and he can go free.

Sounds like a decent setup. It's actually a terrible story. For one thing, the author of Chthon has all of his off-putting tics on display. Seren is a straw woman, whose vocabulary is largely limited to "Yes, Richard," and "No, Richard." The social attitudes of this far future world seem rooted in the Victorian times, with passages like this:

"You'll pose as my wife. Hang on to my arm and–"

"Pose?" she inquired. "I do not comprehend this, Richard."

Damn the forthright Kazo manner! He had five minutes to explain human ethics, or lack of them, to a person who had been born to another manner. Pretense was not a concept in the alien repertoire, it seemed.

He chose another approach. "For the time being, you are my wife, then. Call it a marriage of convenience." She began to speak, but he cut her off. "My companion, my female. On Earth we pair off two by two. This means you must defer to my wishes, expressed and implied, and avoid bringing shame upon me. Only in this manner are you permitted to accompany me in public places. Is this clear?"

And this one:

"I promised to explain why this subterfuge was necessary. I didn't mean to place you in a compromising situation, but–"

"Compromising, Richard?"

"Ordinarily a man and a woman do not share a room unless they are married."

And then, there's the scene where the feminine disguise Richard puts together for Seren falls apart because her body lacks mammalian contours. Why doesn't he then dress her in male clothes? And when her stockings start to fall off her legs, I couldn't help wondering how they'd somehow uninvented Panty Hose in the 21st Century.

But then, I'm not sure if Piers Anthony has actually ever talked to a woman, much less seen her in her underthings.

On top of that, the final revelation that the Earth fleet was never destroyed, but instead went on to conquer Kazo, and the two planets have swapped overlords (both governments populated only by the very best technocrats) is so ridiculous as to beggar belief. That Henrys is invited to become one of the ruling class largely for his novel ideas on how to cut a cake fairly, well, takes the cake.

One star.

Uplift the Savage, by Christopher Anvil

by Kelly Freas

Members of an interstellar agency learn that the best way to increase the technological sophistication of a primitive race is not to give them expertise, but allow them to steal it. The two-page point is hammered in using fourteen pages of digs at women, higher education, and educated women.

One star.

The Inevitable Weapon, by Poul Anderson

by Harry Bennett

A scientist discovers teleportation. Useless for interstellar travel, at least for a while, it's great for beaming in concentrated starlight–as a weapon at first, but potentially, to provide energy.

This would be a decent, one-page Theodore L. Thomas piece in F&SF. Instead, it's fourteen pages of bog-standard detective/secret agent thriller.

Two stars.

Birth of a Salesman, by James Tiptree, Jr.

by Kelly Freas

Jim Tiptee's freshman story is an Anvilesque tale of breakneck pace and nonstop patter. T. Benedict of the Xeno-Cultural Gestalt Clearance (XCGC) has got a tough job: making sure the trade goods of the galaxy not only take into account the taboos or allergies of alien customers, but also the transhipment longshorebeings.

Tedium sets in by page two, which, coincidentally, is how many stars I rate it.

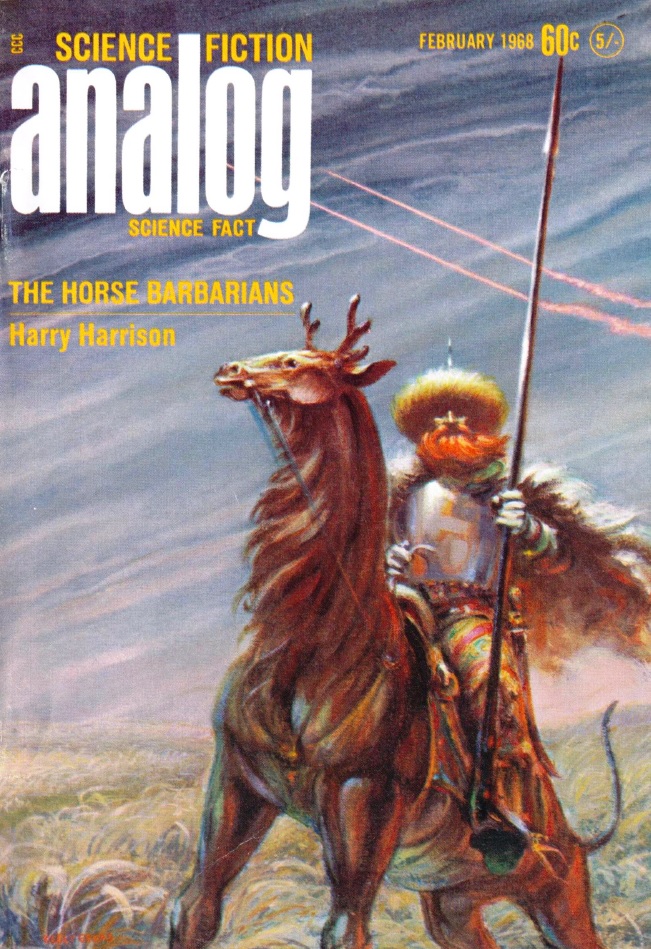

The Horse Barbarians (Part 2 of 3), by Harry Harrison

by Kelly Freas

A lot and very little happen in this installment of Jason dinAlt's latest adventure. Last time on Deathworld III, Jason offered up his fellow Pyrrans as mercenaries to wipe out the horse barbarians on the planet Felicity. It's fair play, after all, since these barbarians (absolutely not the Mongols, because they have red hair!) slaughtered the last attempt at a mining camp on their frozen plateau.

So, Jason accompanies "Temuchin", the warlord, on an expedition down a cliffside to the technologically advanced civilization on the plains below. There, they steal some gunpowder, kill a lot of innocent people, and come back–in time to link up with the rest of the Pyrrans for a raid on the Weasel clan. More slaughter ensues.

Jason feels kind of bad about his part in the killing, but it's all a part of a master plan to someday, eventually, pacify the warriors with by opening up a trade route with the south (as opposed to setting up off-world trade, since the barbarians hate off-worlders). So whaddaya gonna do?

Well, personally? Pick a different career path. Even if the nomads are the biggest savages since the Whimsies, Growleywogs, and Phantasms, what right do the Pyrrans have to kill…anyone?

Setting aside the moral concerns, Harrison is still an effective writer. I wasn't bored, just a bit disgusted.

Three stars.

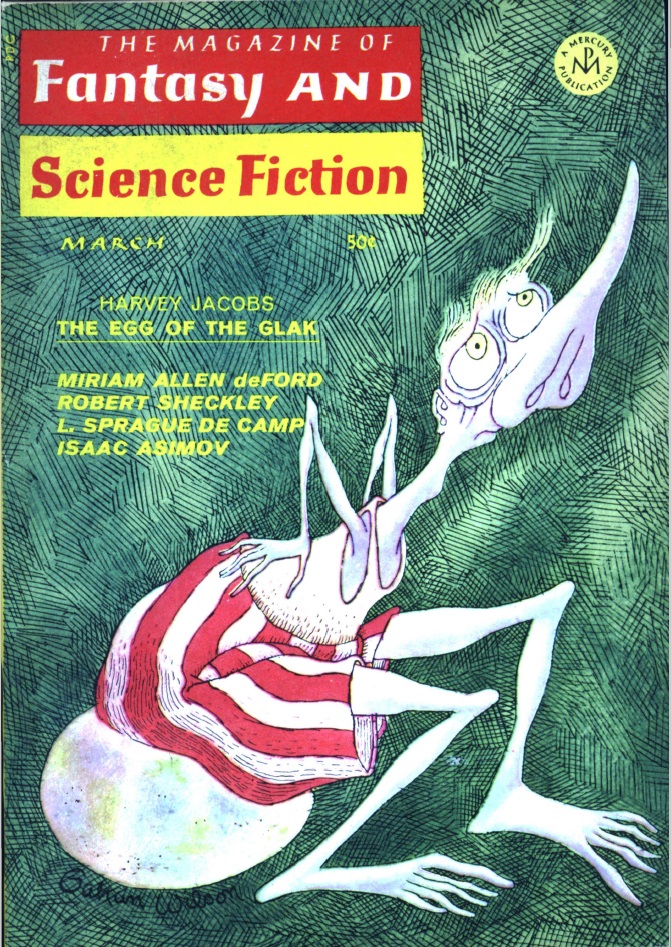

Practice!, by Verge Foray

by Kelly Freas

A shabby little private school for problem children is suddenly the subject of a set of accreditation inspectors. There's nothing wrong with the kids or the staff–the problem is that the snoops might discover it's really a training ground for junior ESPers! Luckily, the tykes are on the side of management, and the inspectors are snowed.

I went back and forth on whether this very Analogian tale deserved two or three stars. On the one hand, I'm getting a little tired of psi stories (the headmaster in the story even says there's no such thing as something for nothing–and that's what psi is), and I resented the smug digs at public school.

But what swayed me toward the positive end of the ledger (aside from the unique and lovely art) was the bit at the end whereby it's suggested that the reason for the school, and the reason psi is so unreliable, is because, like music or language, it's something that needs to be practiced from an early age. It's a new angle, and pretty neat.

So, three stars.

Can't go on…

Wow. 2.1 stars is bottom-of-Amazing territory, and it easily makes this month's Analog the worst magazine of the month. Compare it to Fantastic (2.2), IF (3), New Worlds (3.3), and the excellent Fantasy and Science Fiction (3.6), and the contrast is even stronger.

Because of the paucity of magazines, you could fit all the really good stuff into, say, one issue of Galaxy. On the other hand, women wrote 12% of new fiction this month, which is decent for the times (not to mention the episodes of Star Trek D. C. Fontana has been penning).

It's 1968, an election year. Maybe this is the year Campbell hands the reins over to someone else. It certainly couldn't hurt the tarnished old mag.

And then, maybe the sun will come out again!

Speaking of election news, there's plenty of it and more on today's KGJ Weekly report. You give us four minutes, and we'll give you the world:

![[February 26, 1968] Stormy Weather (March 1968 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/680226cover-672x372.jpg)

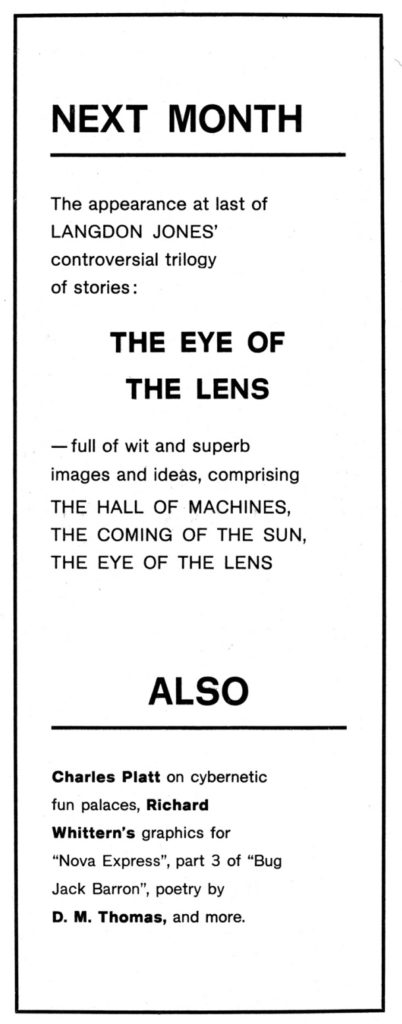

![[February 24, 1968] Sex, Mind-Rape, Sitars and Fun Palaces <i>New Worlds</i>, March 1968](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/New-Worlds-mar-68-672x372.jpg)

Cover by Vivienne Young

Cover by Vivienne Young  Langdon Jones's plot by diagram

Langdon Jones's plot by diagram

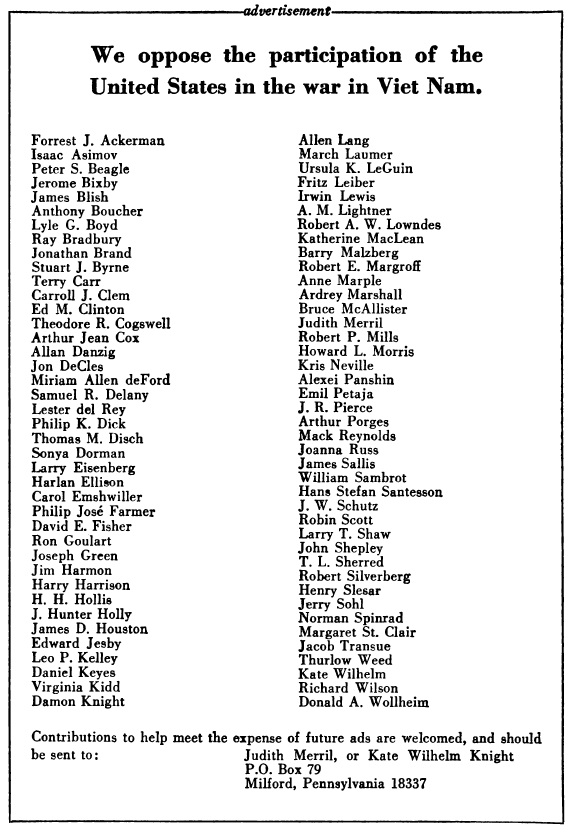

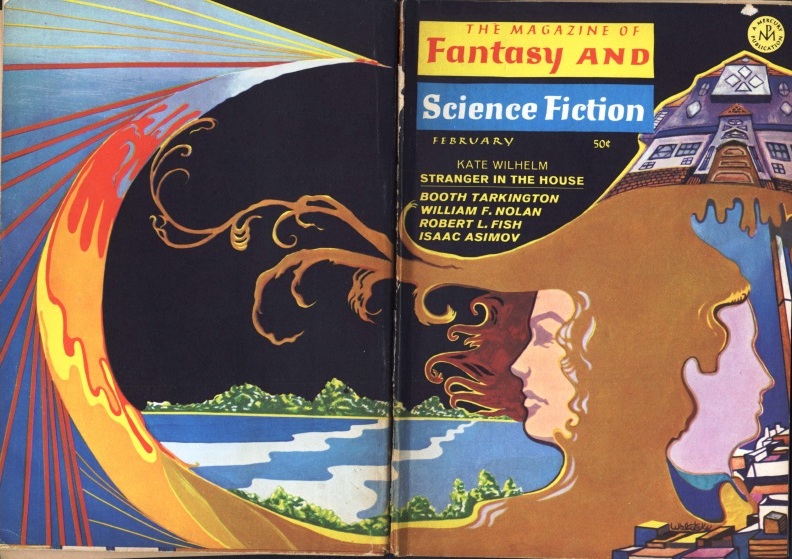

![[February 20, 1968] 1-2-3 What are we fighting for? (March 1968 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/680220cover-671x372.jpg)

![[February 10, 1968] It's a Man's World (March 1968 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/cover-2-672x372.jpg)

![[February 4, 1968] More of the Same (March 1968 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/IF-1968-03-Cover-434x372.jpg)

Dr. Barnard (I.) and Philip Blaiberg (r.), probably before the surgery.

Dr. Barnard (I.) and Philip Blaiberg (r.), probably before the surgery. Dr. Shumway at a press conference last fall (l.), Mike Kasperak and his wife, Ferne (r.)

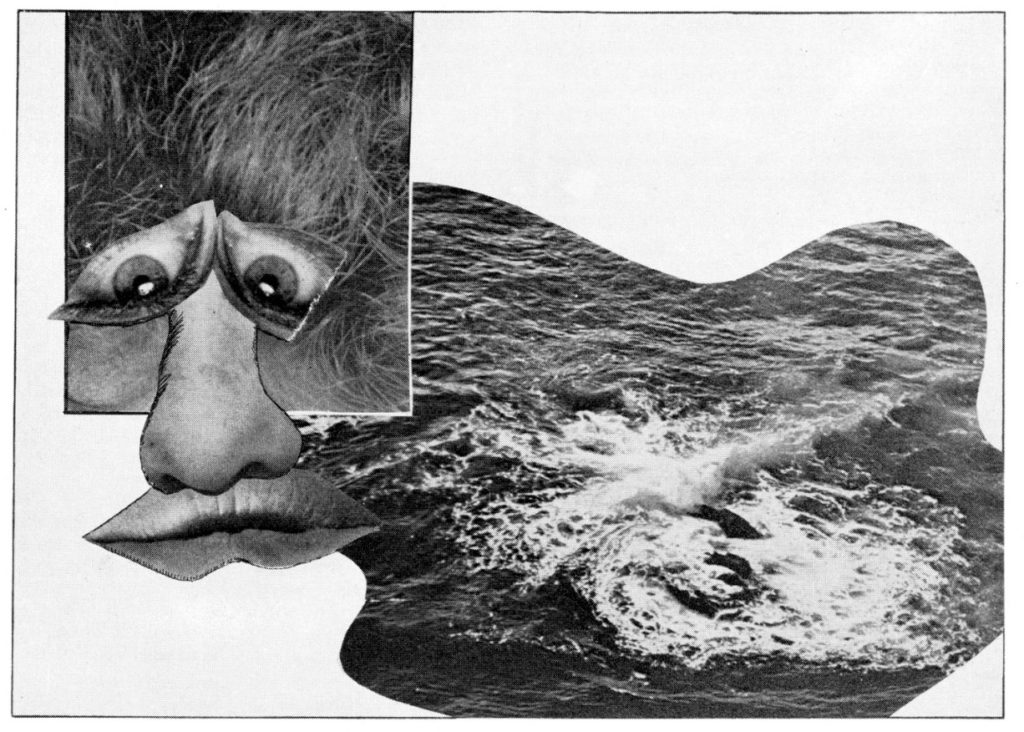

Dr. Shumway at a press conference last fall (l.), Mike Kasperak and his wife, Ferne (r.) This unpleasing collage is for Harlan’s new story. Art by Wenzel

This unpleasing collage is for Harlan’s new story. Art by Wenzel![[January 31, 1968] Too much and too little (February 1968 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/680131cover-651x372.jpg)

![[January 26, 1968] Jack Barron Returns!<i>New Worlds</i>, February 1968](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/New-Worlds-Feb-68-672x372.jpg)

Cover by Eduardo Paolozzi, designed by Charles Platt and Christopher Finch

Cover by Eduardo Paolozzi, designed by Charles Platt and Christopher Finch Photos of the key writers this month. New feature.

Photos of the key writers this month. New feature. More sex from Jack Barron. Artist uncredited.

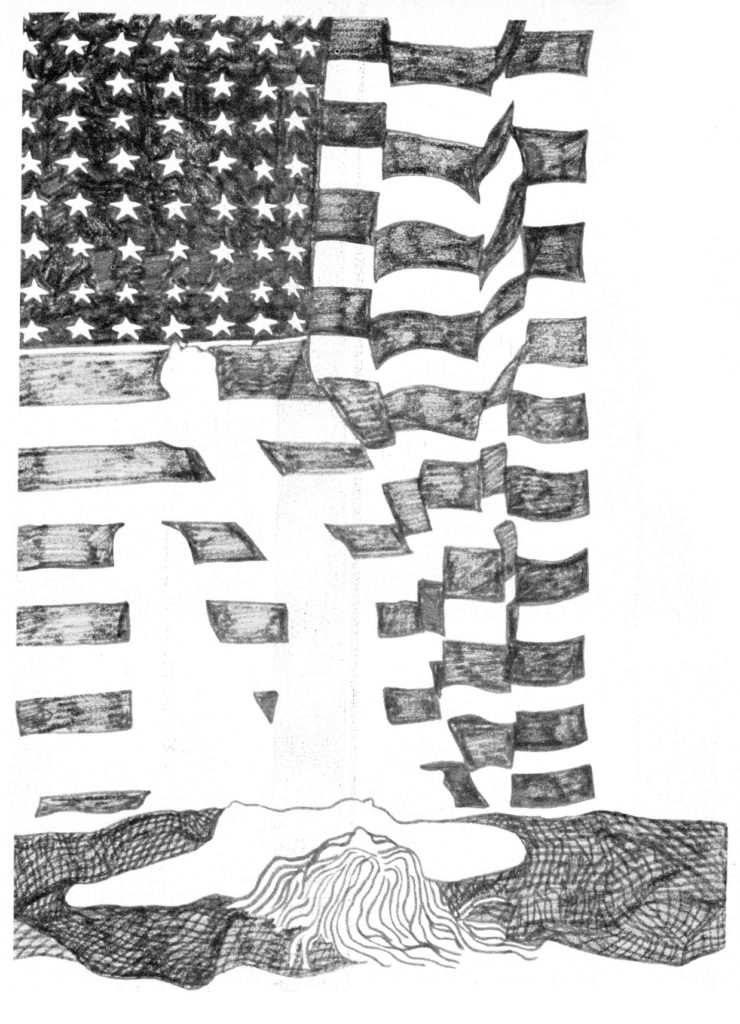

More sex from Jack Barron. Artist uncredited. First page of the article. More cut-up stylings!

First page of the article. More cut-up stylings!

Weird art for a weird story.

Weird art for a weird story.

![[January 22, 1968] The Magical Mystery Tour (February 1968 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>…plus the Beatles movie!)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/680122both-672x372.jpg)

The Mystery Bus attempting to flee its critics.

The Mystery Bus attempting to flee its critics. Yes, but why?

Yes, but why? Everyone having a lovely time, apparently.

Everyone having a lovely time, apparently.![[January 16, 1968] Worthy programming (February 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/680110cover-672x372.jpg)

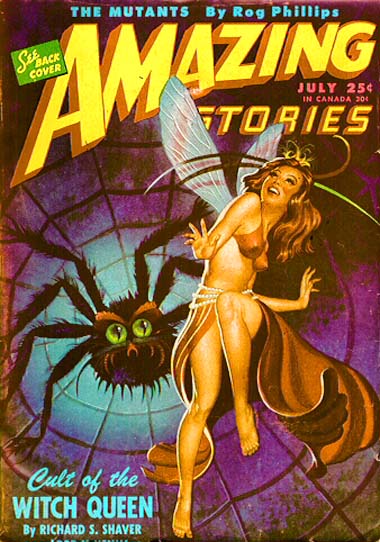

![[January 14, 1968] As Is (February 1968 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/amz-0268-cover-492x372.png)