by Mark Yon

Scenes from England

Hello again!

As Summer draws on, we seem to have got into a somewhat lethargic routine here in Britain. Is it the weather, or is that we are saving our energy for the Worldcon at the end of next month?

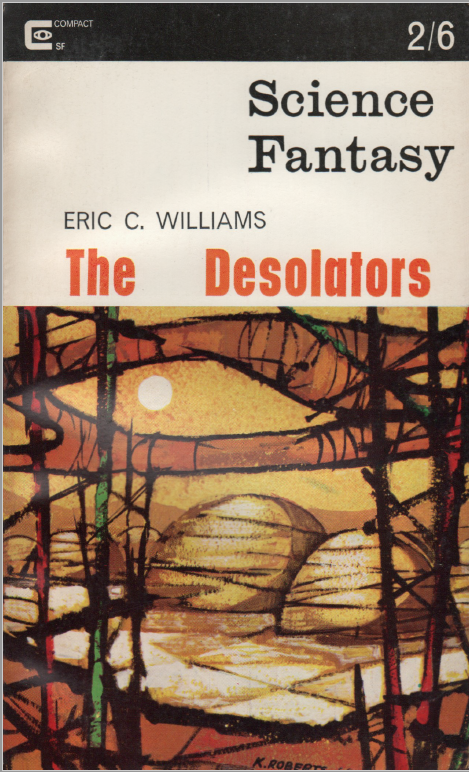

As per usual, the issue that arrived first in the post this month was Science Fantasy..

And we have another Keith Roberts’ cover, this month back to the weird style of the January-June covers. I must be getting used to them – this one’s OK. The light tones reflect the golden Summer us Brits are known to get every year… or perhaps not.

The Editorial this month takes up that idea mentioned a few times by Kyril in previous months. It talks of the 1930's origins of sf before going on to say that sf must evolve from what it was. Like our reading habits change as we grow older and become more mature, so must the genre. As per usual, it is well argued and explained, but nothing that different to what we’ve read recently. It also echoes Mike Moorcock’s rallying call in last month’s New Worlds.

To the stories themselves.

The Desolator, by Eric C. Williams

The first story this month (title on the cover being “The Desolators”, title on the story being the singular) is a Time Travel tale, from an author we last saw in last month’s New Worlds with The Silent Ship.

John Prince is a thief, but one who travels into the past and the future to loot what he needs. On his trail are the Time Police, determined to catch those who profit from other’s work. It’s a nice idea, though one that is pretty much the whole point of the story. There’s a twist in the tale at the end which seemed a little throw-away to me. In summary, it’s OK, but not the best time travel story ever written, nor the best start to an issue of Science Fantasy. 3 out of 5.

Chemotopia, by Ernest Hill

Sometimes the title tells you exactly what the story is going to be. So – Chemicals…drugs… you get the idea. Chemotopia gives us an idea of how crime and punishment could be dealt with in a future society dependent on drugs. Crimes are dealt with on the principle that punishment as vengeance for crimes is outmoded and is being replaced with rehabilitation, chemical usage and reintegration. When a trio of unruly teenagers are arrested for damaging property and injuring people, the view of the older police of what punishment should be utilised is at odds with the modern-day approach. We then go through a number of procedures, involving drugs, to mollify the delinquents. The ending is rather jarring, involving a doctor and a nurse whose attraction may, or may not, be influenced by drugs. It reads like a simpler, less intelligent version of Anthony Burgess’s Clockwork Orange. 2 out of 5.

Idiot’s Lantern, by Keith Roberts

A story from a promising new writer….. well, no.

Another Keith Roberts story, making his grand total of pages in this issue a mere 84 out of 130 pages. But this is another Anita story, the teenage witch who has wound her way through this magazine over the past couple of years. The Idiot’s Lantern of the title is what some call television, and the story is about what Anita and her Granny make of this innovation of the modern age. When they have a television fitted to the cottage, Anita and Granny Thompson become obsessed, to the point that they apply and become contestants on a quiz show recorded in London. Unsurprisingly this causes problems as they go to the big city.

Like all Anita stories, this one might divide opinion, although they are popular. For me it depends on how much Anita’s mentor Granny Thompson appears, as generally the more she’s there, the less I like the story. This story has considerable Granny Thompson presence, but I found it tolerable, though I get the impression that these stories are running out of steam a little. It’s lightly humorous – for some. 3 out of 5.

Paradise for A Punter, by Clifford C. Reed

The title of this one might need a little explaining to non-Anglophiles in that a ‘punter’ is a gambler, someone willing to take a risk. It is important to know that as the story is of Mr. Rogers who seems to be offered a risk he cannot afford to miss, although there’s the inevitable twist in the story expected. A fair Twilight Zone type story. 3 out of 5.

A Way With Animals, by John Rackham

The return of John Rackham, last seen in the March 1965 issue. This is one of John’s more superficial stories about a man who reluctantly takes on responsibility for a pet dragon. Chaos ensues. It’s pretty much what’s expected. I’m tempted to call it a shaggy dog type of story… except it’s about a dragon. 3 out of 5.

Grinnel, by Dikk Richardson

Richardson’s short story in last month’s New Worlds had the dubious honour of getting my first one-star summary. I was hoping that this would be better. It’s not but it is memorable, even if it is not in a good way – a meaningless snippet of a story about a man who seems to drive others insane by repeating the word “Grinnel”. At two pages, at least the story’s not long, but still probably too long. 2 out of 5.

The Furies (Part 2 of 3), by Keith Roberts

You might have noticed that I did enjoy most of Keith’s first part last month. I was interested to see whether his story of giant wasps could maintain the pace of the first part.

Last issue we were left with the cliff-hanger that Bill Sampson and his young friend Jane had made a dash to the coast in order to try and escape the giant wasps and leave the country. Jane had been put upon a boat to France, whilst Bill had returned to England and was grabbed by a group of adults who seemed to be working with a wasp….

So, in this part we widen our perspective and are introduced to a motley crew of various refugees. Bill and his new group are being herded by the wasps to an old Army camp and kept there in order to collect supplies and work for the wasps. The humans seem to adapt to this, although this may be perhaps in some sort of collective shock. Bill and others from his hut in the barracks escape and hide out in caves near Shepton Mallet. They begin to fight back, targeting camps and wasp nests, with varying degrees of success. It ends on another cliff-hanger as Bill tries again to get to the coast to find Jane.

Often in the middle of a story the pace can slow a little. This is not the case here. However, although it might sound like it, this second part is not some boy’s adventure tale, either. It is quite dark with some of the characters clearly traumatised from their experiences, something which Roberts is not afraid to show. There are some shocking moments. 4 out of 5.

Summing up Science Fantasy

Well, we’ve certainly got a range of stories in Science Fantasy this month – time travel, drugs, dragons and giant wasps! However, what we gain in breadth we seem to lack in depth as the other stories are a bit pedestrian, frankly. After a wobbly start, the issue improves as it goes along. I’m pleased that The Furies has managed to keep the momentum of last month’s story going, and I am really looking forward to its conclusion next month.

Let’s go to my second magazine.

The Second Issue At Hand

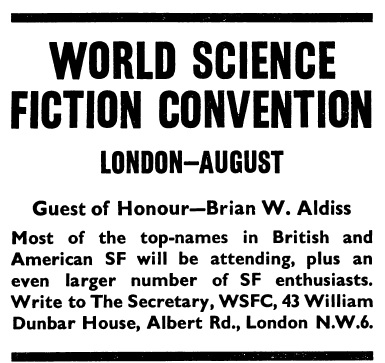

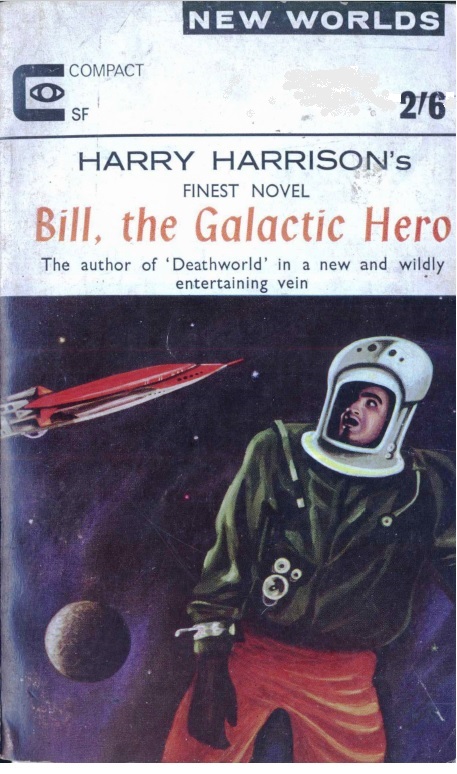

This month’s editorial from Mike Moorcock is one of two halves. The first tells us how great Harry Harrison’s novel is (I’ll comment on that later) before going on to entice us with future attractions. The second part reminds us that we have a Worldcon in London in about one month’s time, which we should be excited about. (Have I said in the last few minutes that Brian will be Guest of Honour at next month’s Worldcon in London?)

We also have the appearance of “Dr. Peristyle” (who is rumoured to be a certain Mr. Aldiss), who will alternate with the Letters Pages in the next few months. His somewhat unique and unusual responses have been great fun in the British Science Fiction Association journal Vector, and I look forward to reading more of them here.

To the stories!

Bill, the Galactic Hero, Part 1, by Harry Harrison

This one, the first of three parts, is heralded with a bit of a flourish. You may have noticed that the front cover of this month’s issue proclaims it as “Harry Harrison’s finest novel”, although to be fair he’s only had three published to date, with similar themes – Planet of the Damned, Deathworld and its sequel Deathworld 2.

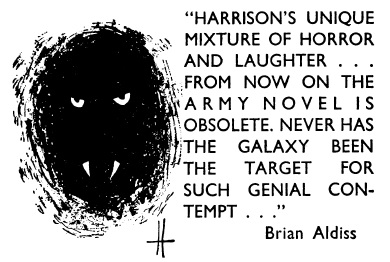

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this novel has been commended by Harry’s friend and co-author, Brian Aldiss! (Have I said in the last few minutes that Brian will be Guest of Honour at next month’s Worldcon in London?)

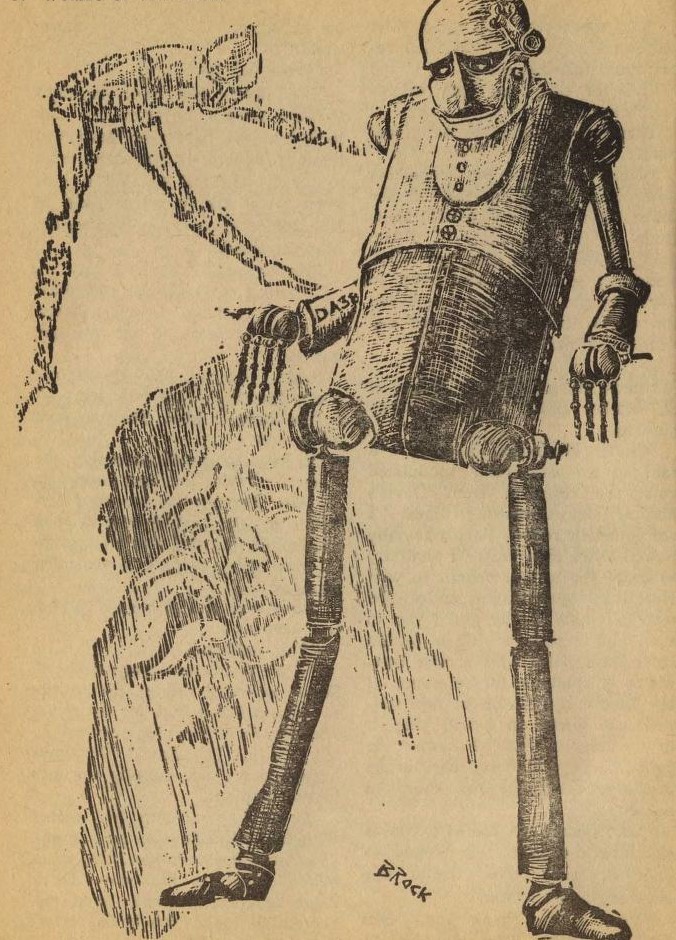

Illustration by Harry Harrison

The bad news is that it is a parody, something that in my experience splits the readership. Some will be impressed by how wittily the author and his prose cocks a snook at the establishment, whilst others will just not find it funny and even rather silly.

Guess which reader I am?

It may be a generational thing. If I was aged twenty-something, I might be amused by the naming of characters such as recruiting 'Sergeant Grue' or 'Petty Chief Officer Deathwish Drang' that good-intentioned Bill encounters as he bumbles his way through military training and active service against the alien Chinger. If I had undertaken National Service, I might be impressed by how the tale repeats real-life tales of bureaucracy and incompetence, amplified to a supersonic level.

But I did not, and as a result it just seems rather silly, and too forced to be funny. I can see what it is trying to do and was a little amused by the jabs at the old guard, but in the end I found it rather monotone and rather relentless. Whilst it did make me think of Robert Heinlein’s Starship Troopers in a new light, I don’t think J G Ballard has much competition here, or even Robert Sheckley! But I did like Harry’s own illustrations. 3 out of 5.

Illustration by Harry Harrison

[This novel appears to be an expansion of The Starsloggers, which appeared in Galaxy last year. I liked it more than Mark, giving it 5 stars, but perhaps it loses something in the lengthening. (Ed.)]

The Source, by Brian Aldiss

Speaking of Harry’s friend…. According to the banner at the top of the story, The Source is an attempt to write a science fiction story based on Jung, which probably would’ve worked more for me had I more than a fleeting knowledge of the philosopher’s ideas. However, from what I've read here this seems to involve sex, nakedness and your mother, in various dream-like states. As this is an sf magazine, though, we have all of that bolted on to a notional science fiction idea of aliens visiting Earth and trying to determine what they see. Not one of Brian’s best, but I was a little hamstrung here by my limited knowledge of philosophers. 2 out of 5.

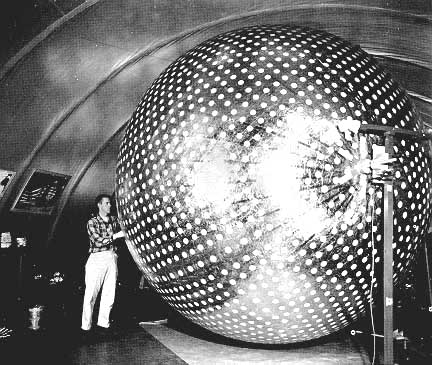

And Worlds Renewed, by George Collyn

The reappearance of George after his book reviews last month. This story seems to show the sinuous relationship between decadence and art, for in this future culture and artistic reputation can be determined by the work of an artist on a planet sized scale. Nefo Seteri is commissioned to complete a commission on Rigel XXII by a man-with-more-money-than-sense, Junter Firmole. The project is completed by Seteri in secret, until the grand unveiling, which is the surprise ending. It’s really a one-idea story, with lots of description about Seteri’s process, leading to the conclusion, the ultimate in narcissistic planet-shaping. I did wonder how one would go about keeping some art this big a secret. 3 out of 5.

The Pulse of Time, by W. T. Webb

A weird but short story of a prominent heart surgeon who is offered a job by a mysterious benefactor. When they meet, the surgeon is shown what I will describe as a life-clock, running by being connected to a living heart. Where the heart that powers the clock comes from is the big reveal at the end. 3 out of 5.

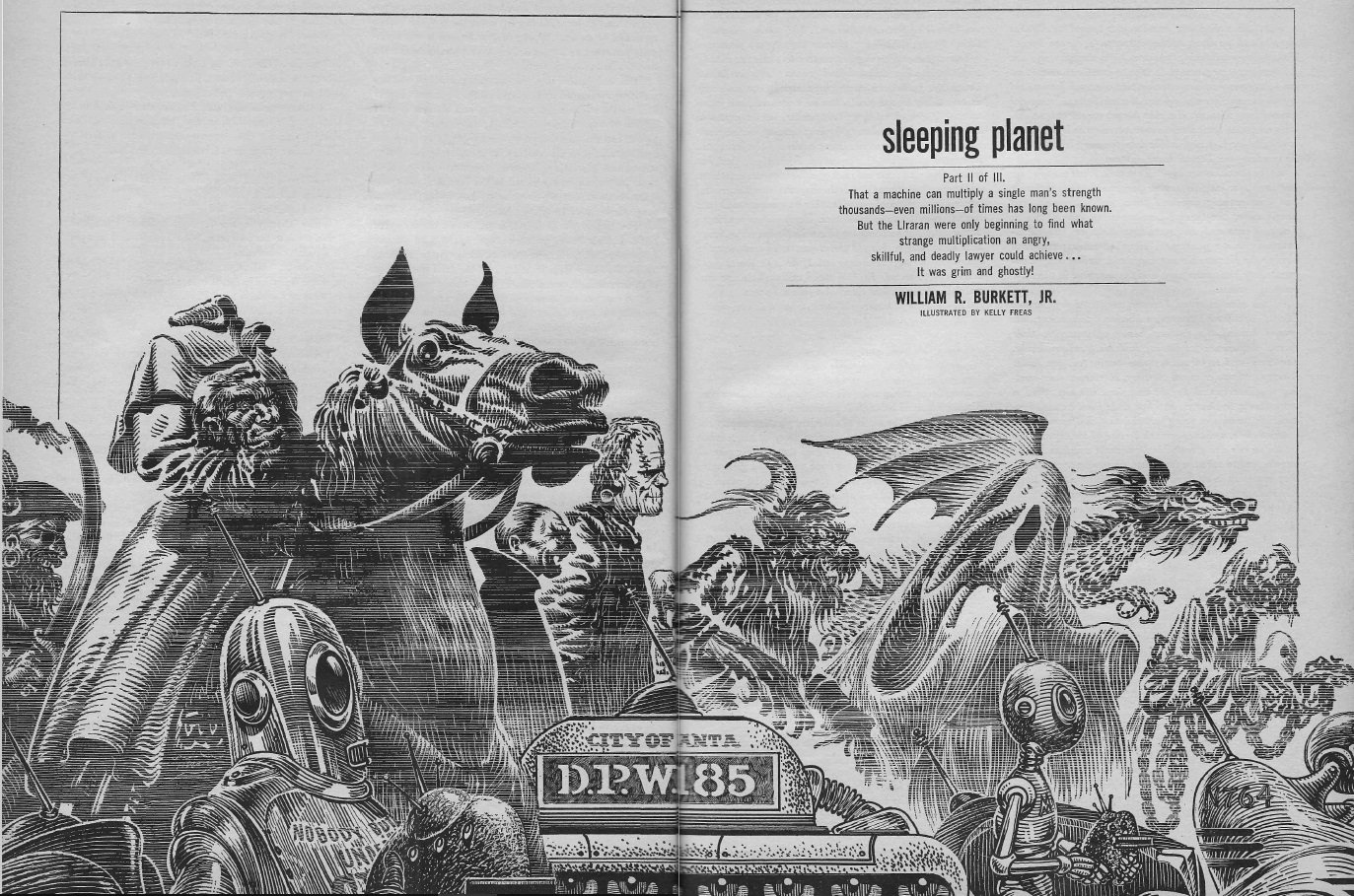

By The Same Door, by Mack Reynolds

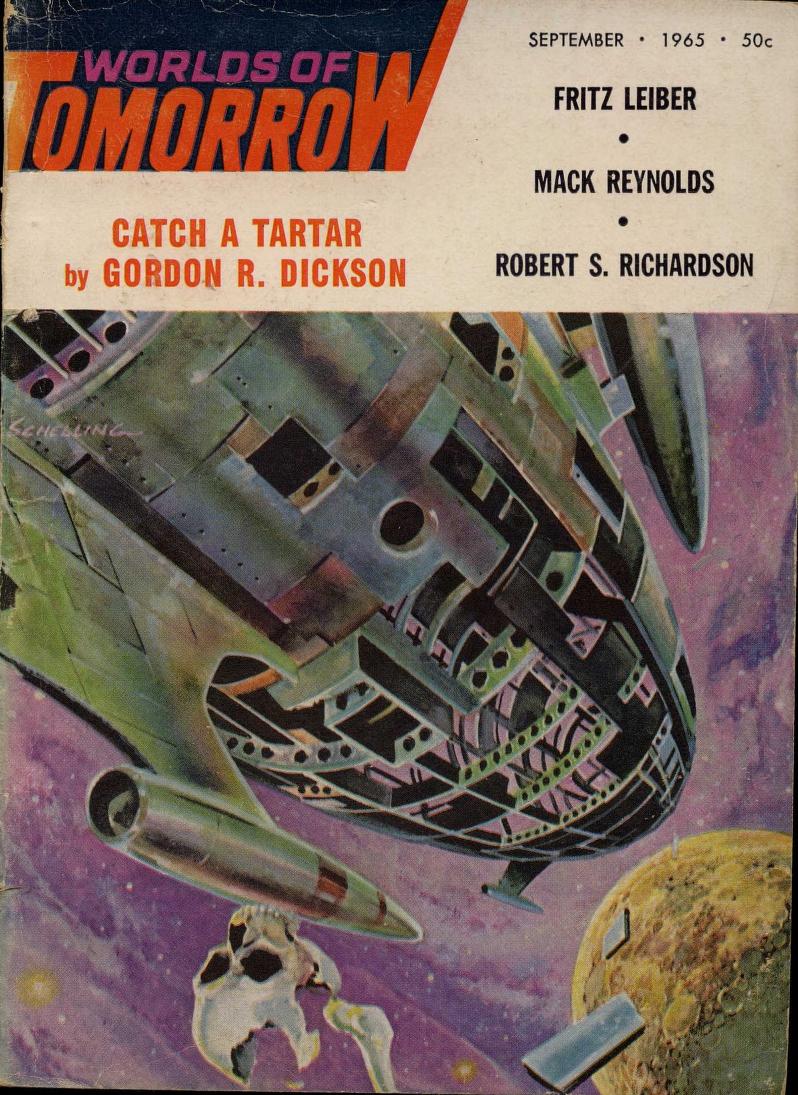

Another attempt by Moorcock to sneak an American author into this British magazine? (Mind you, it has worked for Vernor Vinge from a couple of issues ago, who, as you will see later, did very well in that issue’s ratings.)

However, this one's not great. This is a story about an unpleasant man, Mr. Bowlen, who insists on Alternatives Inc. honouring its promise to customers of being able to put someone in any world they want. Bowlen demands to be sent to a place where some “secret perversion” that he has read about takes place. The difficulty for the company is that he never found out what the secret perversion was, exactly. And neither do we, in this story that sputters out to no real resolution. 2 out of 5.

Preliminary Data, by Mike Moorcock

I’m amazed that the editor has time to write as well these days, but here’s a Jerry Cornelius story that combines the action of The Avengers TV series with modern cultural references and religion. It is difficult to describe, but involves stylishly trendy modern icon Jeremiah Cornelius and his wife Maj-Britt appearing to be kidnapped by Miss Brunner and taken to Finland. In actual fact, they have had nothing of the sort happen and are actually involved in creating some sort of god-like superhuman.

This is one of those stories where everything seems to have been thrown in. There's some meanderings on the cyclical nature of cosmology and religion, combined with contemporary cultural references and the perhaps inevitable psychedelic dream sequences. It should be a combination I dislike, but I was impressed by the fast-pace and enthusiasm of it all. Rather odd, but I liked it. 3 out of 5.

Songflower, by Kenneth Hoare

The title gives this one away, a minor tale of what happens to sailors – sorry, spacemen – when they call into port. In this case, they spend time in bars with aliens and then get fleeced by local traders with an alien singing plant. 3 out of 5.

Book Reviews, Articles and Dr. Peristyle

In the reviews this month James Colvin (aka Mike Moorcock – how does he manage the time?) evaluates H L Gold’s story collection The Old Die Rich and the “undemanding” fourth volume in the New Writings in SF series edited by John Carnell.

New name Ron Bennett reviews The Joyous Invasions by Theodore Sturgeon in some detail. Hilary Bailey (aka Mrs. Moorcock) reviews The Screaming Face by John Lymington, The Thirst Quenchers by Rick Raphael and the ‘frightening’ Paper Dolls by L. P. Davies.

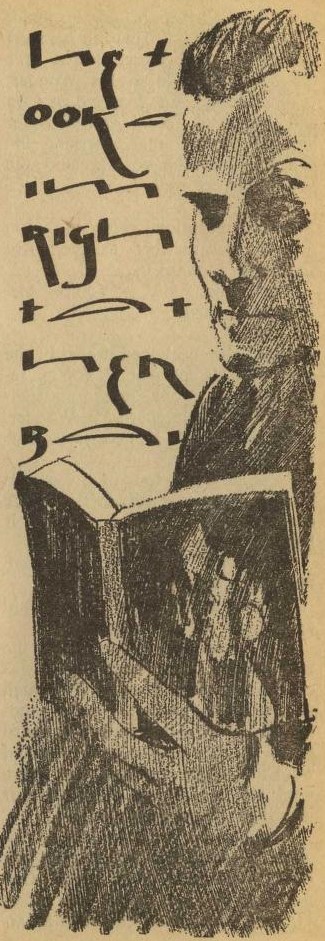

So to Dr. Peristyle. This perhaps has to be read, rather than described:

As you can see from the extract above, here the not-so-good Doctor answers, in his acerbic style, questions asked by readers. It’s all in good-humour and a little silly, but it made me smile.

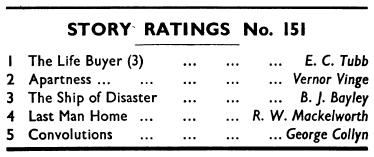

In terms of Ratings, no great surprises for issue 151 from June.

But as I mentioned earlier, hasn't Vernor done well? I expect to see more American authors in the future.

Summing up New Worlds

How much you like this issue will depend on how much you like Bill, the Galactic Hero. It dominates the issue in terms of pages, although there is a little variety in terms of the shorter stories. I liked the Moorcock, which I was surprised to find that I liked more than his other material of late, and would happily read more of the free-wheeling, asexual, anti-hero Jerry Cornelius in the future.

The message is clear, though – this ‘new’ New Worlds is not afraid to make fun of what has come before it, as it sets off to blaze a new trail. It’s edgy and a little cynical, although at the same time rather British in its gentle manner of knocking down precious icons of the science fiction world.

Summing up overall

Both issues have their strengths and weakness this month. However, the continued excellence of The Furies means that this month’s best issue for me is Science Fantasy.

And that’s it for this time. I'm off to get more British sun!

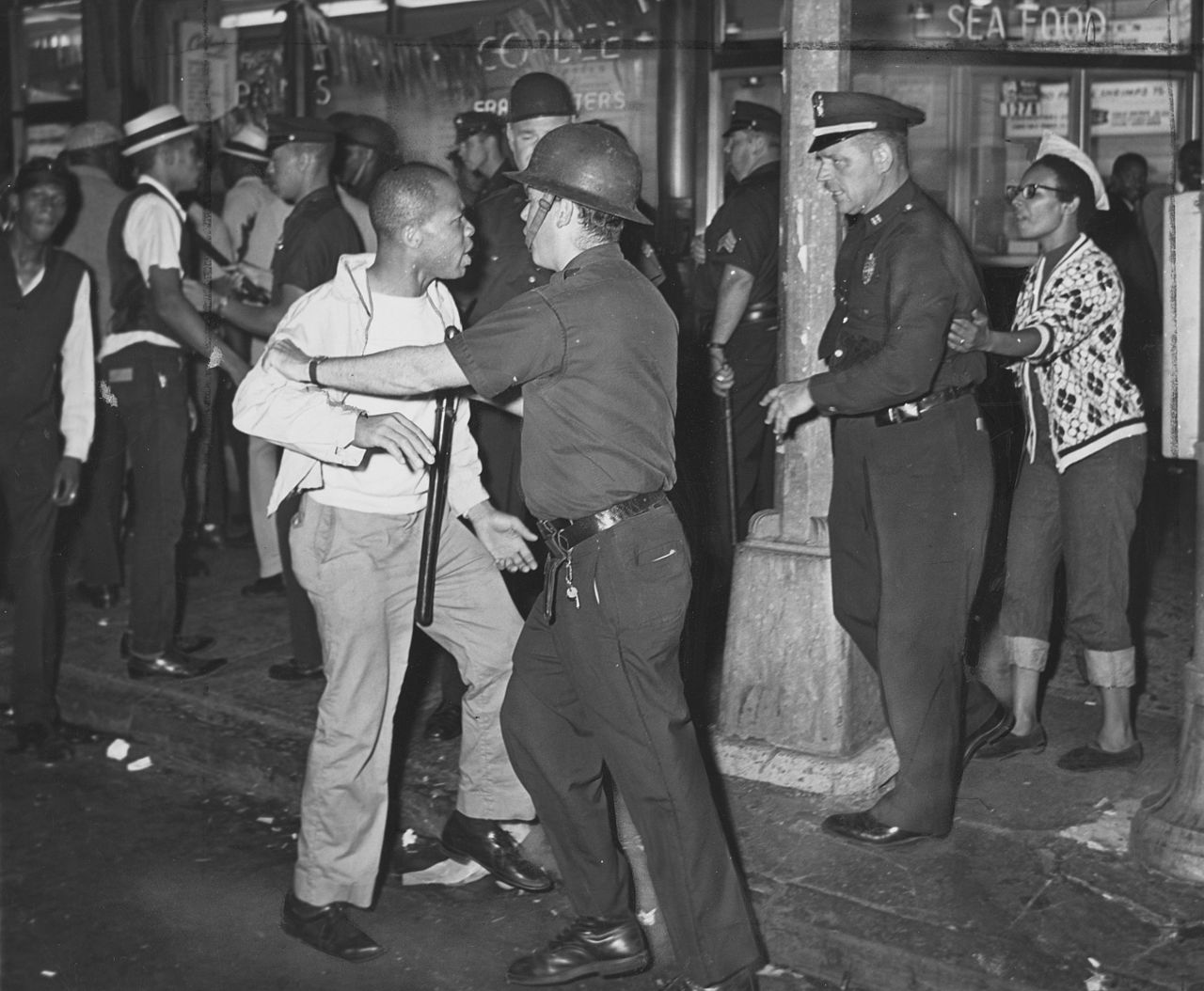

A snapshot of Margate this summer.

(Or perhaps not.)

Until the next…

(come join us in Portal 55, Galactic Journey's virtual lounge!)

![[July 28, 1965] Aldiss, Harrison, and Roberts, Inc. (August 1965 <i>Science Fantasy</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/650728cover-672x372.jpg)

![[July 18, 1965] The Prodigal Returneth (September 1965 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v03n03_1965-09_0000-2-672x293.jpg)

![[May 14, 1965] Keep A Civil Tongue In Your Head (July 1965 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v03n02_1965-07_0000-2-672x318.jpg)

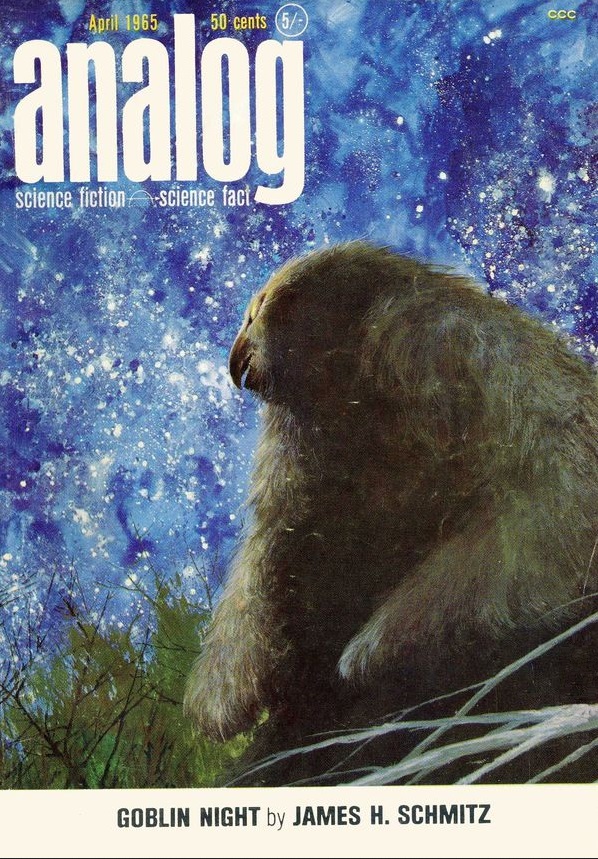

![[March 30, 1965] Suborbital Shots (April 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/650330cover-598x372.jpg)

![[January 31, 1965] Janus, Facing Both Ways (February 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/650131cover-672x372.jpg)

![[November 29, 1964] All-star (December 1964 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/641129cover-672x372.jpg)

![[October 30, 1964] The Deadly Barrier (November 1964 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/641030cover-672x372.jpg)

![[October 2, 1964] Terrestrial Adventures (October 1964 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/641002cover-672x372.jpg)

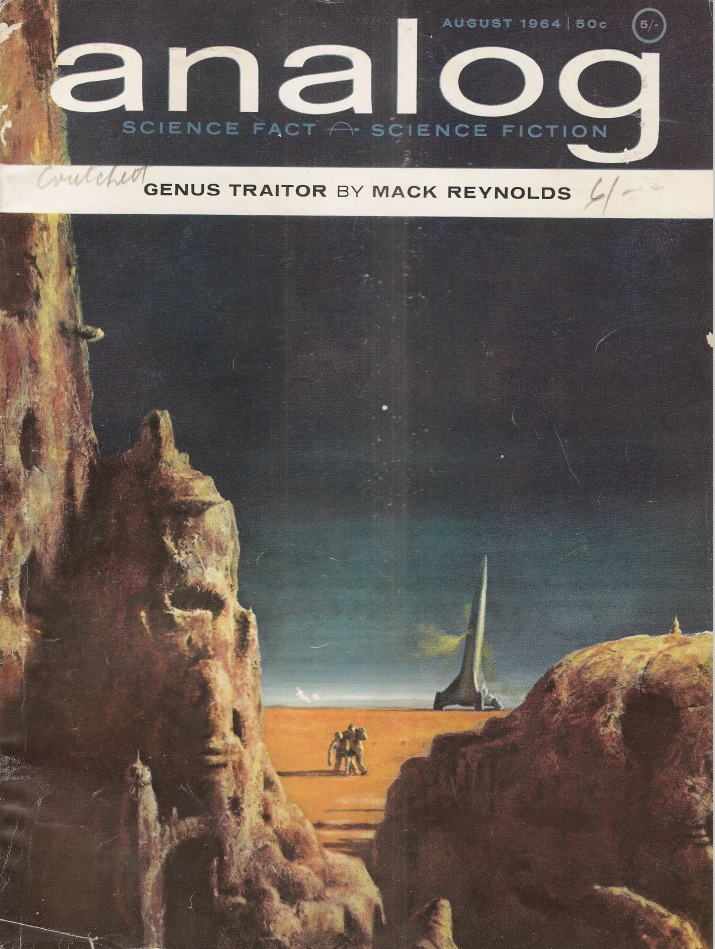

![[August 3, 1964] Running hot and cold (August 1964 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/640803cover-672x372.jpg)

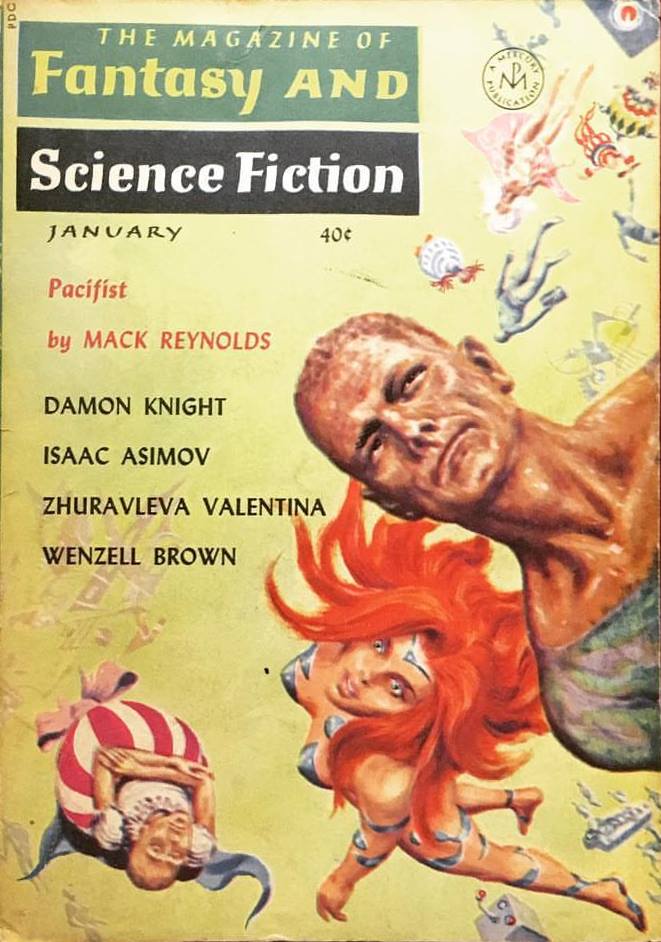

![[December 21, 1963] Soaring and Plummeting (January 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/631221cover-661x372.jpg)