by Gideon Marcus

A little goes a long way

Science fiction has a reputation for being a serious genre. In tone, that is–it's still mostly dismissed by "serious" literary aficionados. Whether it's gloomy doomsday predictions or thrilling stellar adventure, laughs are usually scarce.

There is, however, a distinct thread of whimsy within the field. Satire and farce can be found galore. For instance, Robert Sheckley was a master of light, comedic sf short stories in the '50s (he's less good at it these days). In moderation, fun/funny stories break up a turgid clutch of dour tales.

On the other hand, when you put a bunch together, particularly when only one of them is above average…

You get this month's issue of Galaxy.

You're too much, man

by Jack Gaughan

Before we get to the stories, in his editorial column Fred Pohl reminds Galaxy readers to submit proposals for the ending of the Vietnam War…in 100 words or fewer.

It makes me want to send something like this (with apologies to Laugh-In:

How I would end the War in Vietnam, by Henry Gibson.

"I would end the War in Vietnam by bombing the Vietnamese. I would bomb them a lot. When there are no more Vietnamese, we would win."

Thank you.

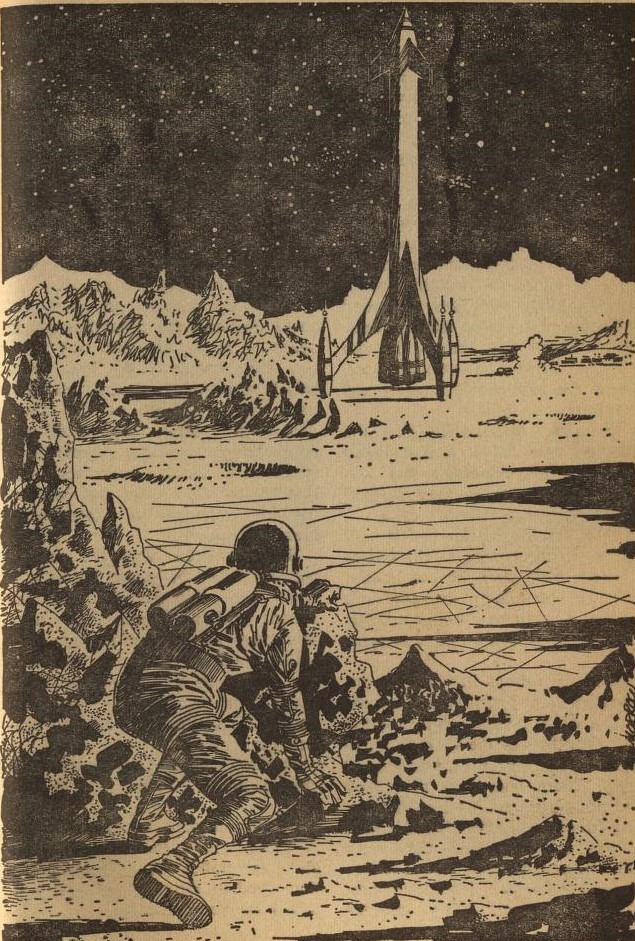

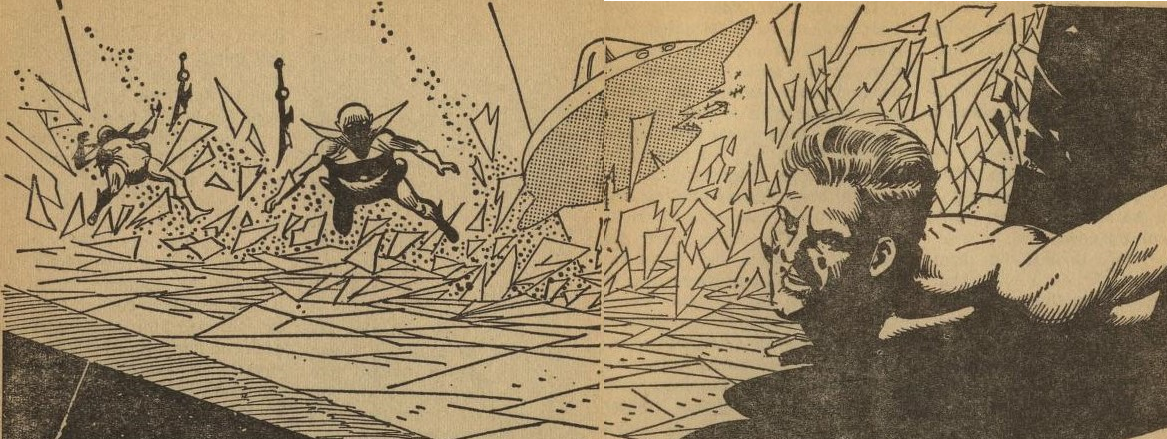

A Specter is Haunting Texas (Part 1 of 3), by Fritz Leiber

by Jack Gaughan

The lead piece is the beginning of a new serial by one of the old titans of science fiction. It tells of one Christopher Crockett de la Cruz, an actor from a space colony orbiting the moon. He has come down to Earth to ply his trade, a very risky endeavor as even lunar gravity is uncomfortable for him. De la Cruz requires an integrated exoskeleton to get around. That plus his emaciated, 8-foot frame makes him look like nothing so much as Death himself. A handsome, well-featured Death, but Death just the same. (Hmmm… a handsome, gaunt actor–I wonder on whom this character could be based!)

As strange as De la Cruz is, the situation on Earth is even stranger. He makes touchdown in Texas, now an independent nation again in the aftermath of an atomic catastrophe in the late '60s. Its inhabitants have all been modified to top eight feet as well (everything is bigger in Texas, by God's or human design), and they claim sovereignty of all North America, from the Guatemalan canal to the Northwest Territory. And over the Mexicans in particular, who not only are excluded from the height-enhancing hormone, but many of whom are forced to live as thralls, harnessed with electric cloaks that make them mindless slaves.

Quickly, De la Cruz is embroiled in local politics, unwittingly used to spearhead a coup against the current President of Texas. Along the way, the descriptions, the events, the setting are absurd to the extreme–from the reverence paid to "Lyndon the First", father of the nation, to the ridiculous courtships between De la Cruz and the two female characters.

It shouldn't work, and it almost doesn't, but underneath all the silliness, there is the skeleton of a plot and a fascinating world. It doesn't hurt that Leiber is such a veteran; I've read froth for froth's sake, and this isn't it. I'm willing to see where he goes with it.

Three stars.

McGruder's Marvels, by R. A. Lafferty

by Joe Wehrle, Jr.

The military needs a miniaturized component for its uber-weapon in two weeks, but the regular contractors can't guarantee delivery for two years. The colonels in charge of procuring reject out of hand a bid that will provide parts for virtually nothing and almost instantly. It is only when they start losing a global war that they grasp at the seemingly ludicrous straw.

Turns out the fellow who made the bid used to run a flea circus. Naturally, now he's into miniaturization. His parts really do work, and they really are cheap, but as can be expected, there's a catch.

If I hadn't known this story was written by Lafferty, I'd still have guessed it was written by Lafferty. After all, he and whimsy are old companions. It's more of an F&SF fantasy than SF, but it at least has the virtue of being memorable. Three stars.

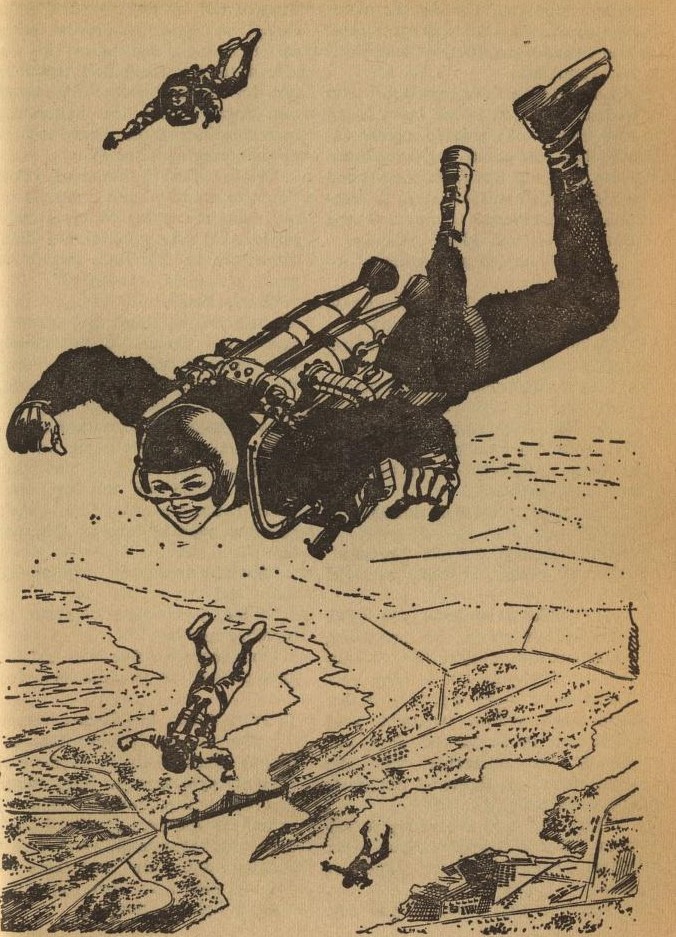

There Is a Tide, by Larry Niven

by Jeff Jones

The best piece of the issue is this one, featuring a new Niven character (the 180-year-old space prospector Louis Wu) in a familiar setting (Known Space). This is set later than the rest of the stories, past the Bey Schaeffer tales, contemporaneous with Safe at Any Speed somewhere close to the year 3000.

Wu has gotten tired of people, and so he has gone off in his one-man ship to explore the stars. His motive is fame–he wants to find himself a relic of the Slavers, the telepathic race of beings who ruled the galaxy and died in an interstellar war more than a billion years ago. In a far off system, his deep radar pings off an infinitely reflective object in orbit around an Earthlike world. Assuming it's a Slaver treasure box, kept in stasis these countless eons, he moves in for the salvage. But a new kind of alien has gotten there first…

Once again, Niven does a fine job of establishing a great deal with thumbnail, throwaway lines. In the end, Tide is a scientific gimmick story, the kind of which I'd expect to find in Analog (why doesn't Niven show up in Analog?), but the personal details elevate the story beyond its foundation.

It's funny; I read in a 'zine (fan or pro, I can't remember) that Niven writes hard SF that eschews characterization. I think Niven writes quite unique and memorable characters and hard SF. It's a welcome combination.

Four stars.

Bailey's Ark , by Burt K. Filer

by Brock

Now back to silliness. Atomic tests have caused the oceans to flood the land. After a few decades, only a few mountaintop communities are left, and soon they will be inundated. Fourteen humans have been chosen to be put into cold storage for 1500 years, to emerge when the waters have receded.

All the animals have died, except for a few caged specimens, and no effort has been made to preserve them through the impending apocalypse. It's up to one wily vet to save at least one species by sneaking it into the stasis Ark without anyone noticing.

Everything about this story is dumb, from the set up to the execution. Its only virtues are that it's vaguely readable and that it's short.

Two stars.

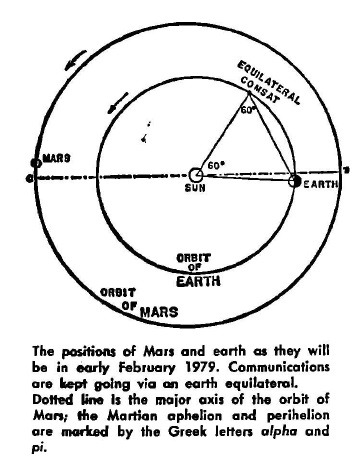

For Your Information: Interplanetary Communications, by Willy Ley

This is a strange article which never quite makes a point. The subject is sending messages from points around the solar system, but ultimately, Ley presents just two notable things:

1) A table of interplanetary distances (available in any decent astronomy book, and without even a convenient translation of kilometers to light-seconds/minutes/hours).

2) The assertion that satellites, artificial or natural, will be necessary as communications relays as direct sending of messages from planetary surface to planetary surface is prohibitively power-intensive. It is left to the reader's imagination as to why that would be.

Sloppy, rushed stuff. Two stars.

Dreamer, Schemer, by Brian W. Aldiss

Two captains of industry vie for control of a city. One offers a collaboration; the other takes advantage of the offer, double crosses the offerer, and leaves him penniless. When the double-crosser gets second thoughts, he subjects himself to a "play-out", a sort of mind trip where he gets to recreate and re-examine his decision in a fantasy world scenario. The double-crossed, coincidentally, engages in a "play-out" at the same time, for the same reason.

This concept was done much more effectively more than a decade ago in Ellison's The Silver Corridor. Two stars.

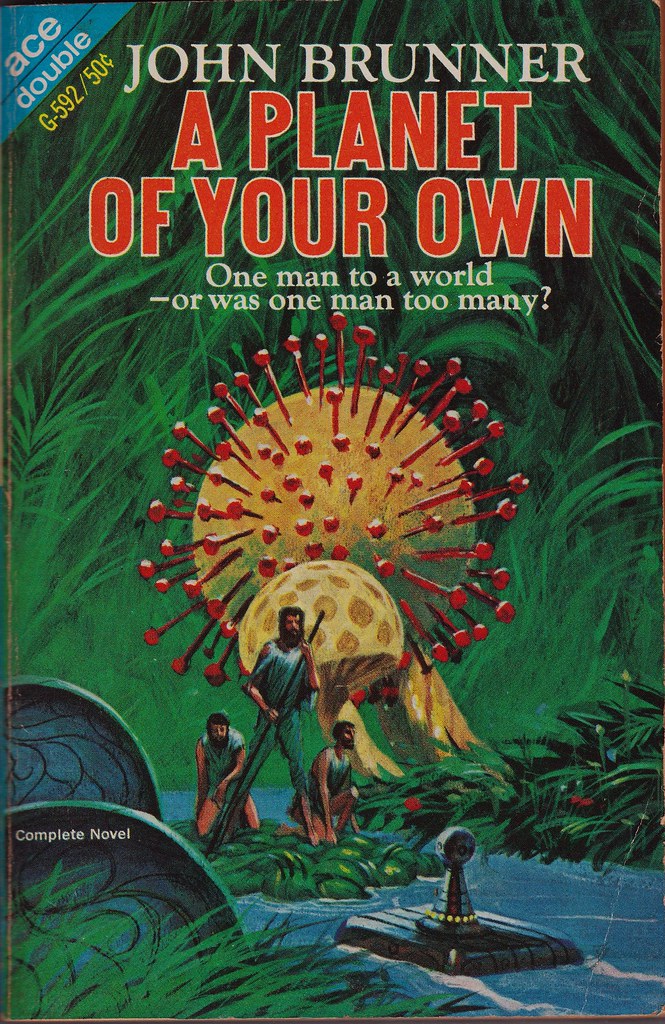

Factsheet Six, by John Brunner

by Jack Gaughan

A callous capitalist comes across "Factsheet Five", a rudely typed circular that details all the horrible injuries caused by the defects in various companies' products. This and the prior Factsheets have had harmful impacts on the companies listed, from financial loss to outright bankruptcy. The capitalist, who has his own industrial empire (and attendant quality-control issues), wants to find the author of the Factsheets so he can get inside knowledge to make a killing in the investor market.

Of course, we know who will be featured in Factsheet Six…

This is the kind of corny, Twilight Zone-y piece that shows up in the odd issue of F&SF. I was sad to find it here.

Two stars.

Seconds' Chance, by Robin Scott Wilson

by Brand

Ever wonder who cleans up after the James Bonds and Kelly Robinsons of the world, settling insurance claims, smoothing diplomatic feathers, etc.? This is their story.

Their rather pointless, one-joke-spread-over-too-many-pages, story.

Two stars.

When I Was in the Zoo, by A. Bertram Chandler

by Vaughn Bodé

Here's a shaggy dog story, told White Hart style, about an Aussie fisherman who gets abducted by jellyfish aliens, exhibited in a zoo with a collection of terrestrial animals, and then seduced for professional reasons by one of the lady jellyfish.

Frankly, I'm not quite sure what else to say about it other than it's the sort of tale you'd expect from A. Bertram Chandler writing a White Hart story–competent, maritime, Australian, and forgettable.

Three stars.

2001: A Space Odyssey, by Lester del Rey

The issue ends with a review panning 2001 as New Wave nihilism, meaningless save for the vague suggestion that intelligence is always evil. This is a facile take. It's possible 2001 is what I call a "Rorschach film", like, say, Blow Up, where the director throws a bunch of crap on the screen and leaves it to the viewer to invent a coherent story. However, there are enough clues throughout the film to make the film reasonably comprehensible. Moreover, there is a book that explains everything in greater detail.

I'm not saying 2001 is perfect, and I imagine those who had to sit through the longer, uncut version enjoyed it less (save for Chip Delany, who apparently preferred it. I'll never know which I would have liked best, since the director not only trimmed down the film after release, but burned the cut footage!) But it is a brilliant film, extremely innovative, and it's worth a watch.

Starving for a bite

After eating all that cotton candy, with only the smallest morsel of meat to go with it, I am absolutely famished for something substantial. Thankfully, I'm about to hop a Boeing 707 for a trip to Japan, where not only the food will be exquisite, but I can catch up on all the 4 and 5 star stories recommended by my fellow Travelers in earlier months.

Stay tuned for reports from the Orient!

![[June 10, 1968] Froth and Frippery (July 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/680610cover-653x372.jpg)

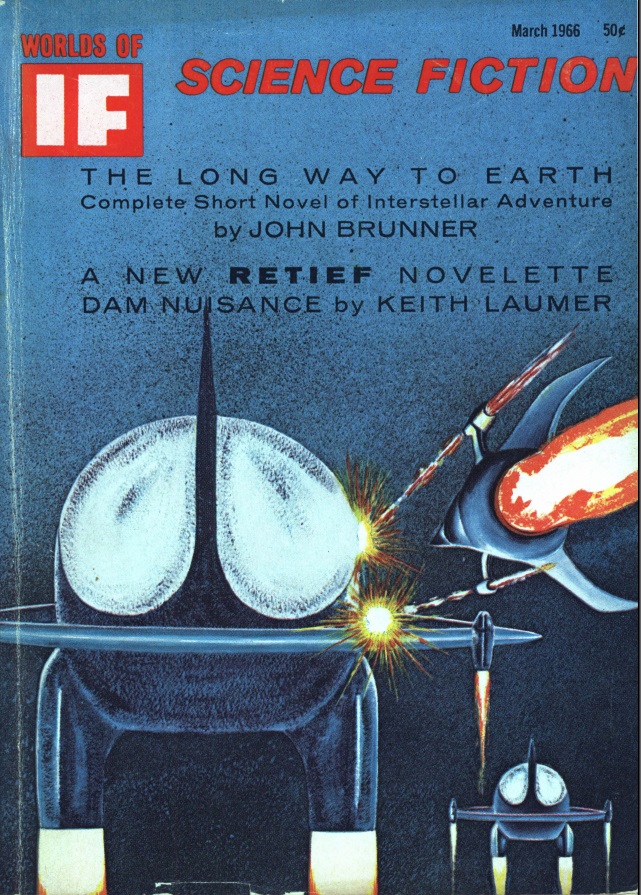

![[June 2, 1968] Necessary Evils (July 1968 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/IF-1968-07-Cover-543x372.jpg)

The Baltimore Nine shortly after their arrest. Fr. Philip Berrigan is 2nd from the left in the back row.

The Baltimore Nine shortly after their arrest. Fr. Philip Berrigan is 2nd from the left in the back row.

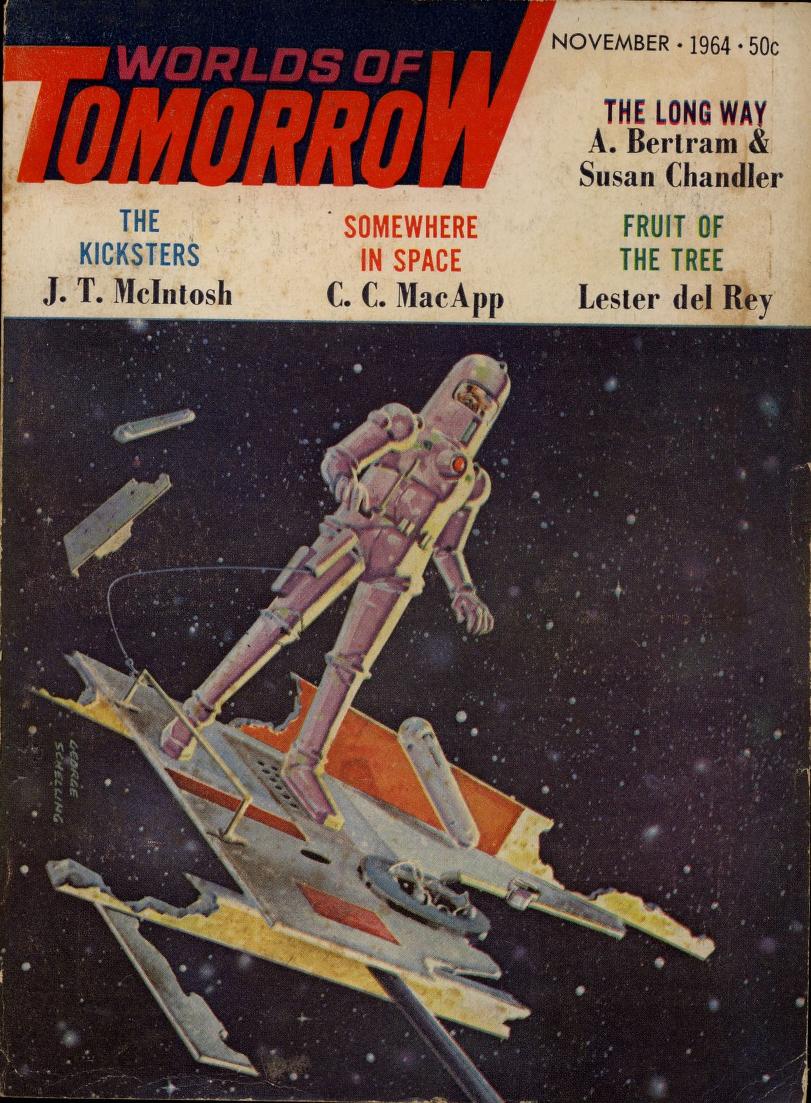

Abbott and his men are the first to reach the Sleeper’s chamber. Art by Gray Morrow

Abbott and his men are the first to reach the Sleeper’s chamber. Art by Gray Morrow![[November 20, 1967] Fresh Air? (December 1967 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/amz-1267-cover-497x372.png)

![[October 10, 1967] Jack the Ripper and Company (<i>Dangerous Visions</i>,Part One)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/1967_Dangerous-Visions-hc-2-672x372.jpg)

![[October 2, 1966] At Heart (November 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/IF-1966-10-Cover-646x372.jpg)

![[September 10, 1966] Bon appetit! (this month's Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/660910covers-672x372.jpg)

![[June 2, 1965] Heck in a Handbasket (July 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/1965-07-IF-cover-653x372.jpg)

![[November 15, 1964] Veteran's Triumph (December 1964 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/641115cover-432x372.jpg)

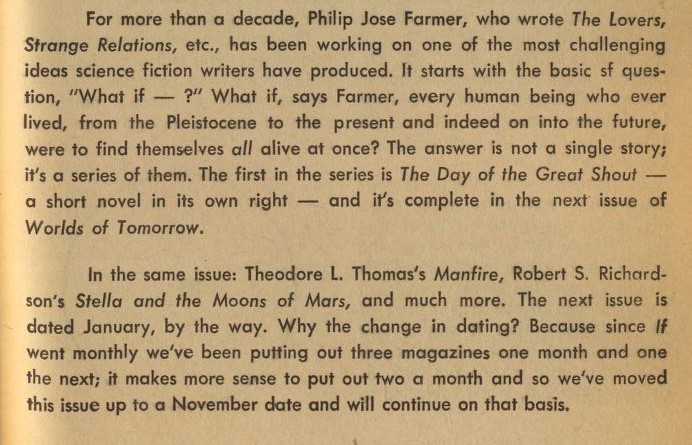

![[September 16, 1964] The Waiting Game (November 1964 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/worlds_of_tomorrow_196411-3.jpg)

![[April 14, 1964] COOKING WITH ASH (the May 1964 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/640414cover-672x372.jpg)