by Gideon Marcus

Hot Times

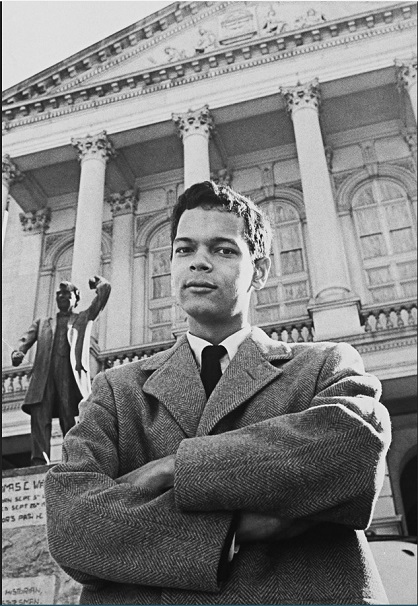

Summer is looming, and it looks like we're in for another riot season. I suppose it only stands to reason given that inequality still runs rampant in a nation ostensibly dedicated to equality. This time, the outrage boiled over in Chicago, and the group involved was of Puerto Rican extraction.

Things started peacefully, even jubilantly: June 12 saw thousands gather for the Puerto Rican pride parade. But after the festivities, the cops shot Cruz Aracelis, 21, and violence erupted. For three days, police cars were overturned, property went up in flames, and people were hurt (and some died). Despite the exhortations of the community's leaders, the rioting continued, and it was not until Mayor Daley promised much-needed reforms that the outbreaks lapsed, on June 15.

Tectonic shifts are rarely gradual. Similarly, we lurch toward progress with the accompanying devastation of an earthquake. Just as we're starting to build for seismic destruction in California, if we want to see riot summers a thing of the past, we'll need to build real systems for equality sooner rather than later.

Eye of the Storm

Chicago may burn, Kansas may be savaged by tornadoes, and Indonesia might be going to hell in a hand basket, but the latest Fantasy and Science Fiction is by comparison pretty mellow stuff. Indeed, it's a pretty unremarkable issue even compared to recent issues of F&SF! Still, there's good reading in here. Take a break from the outside world's madness and join me:

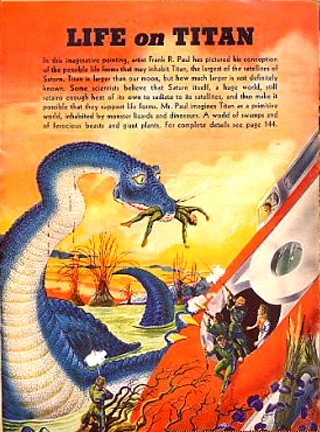

by Chesley Bonestell

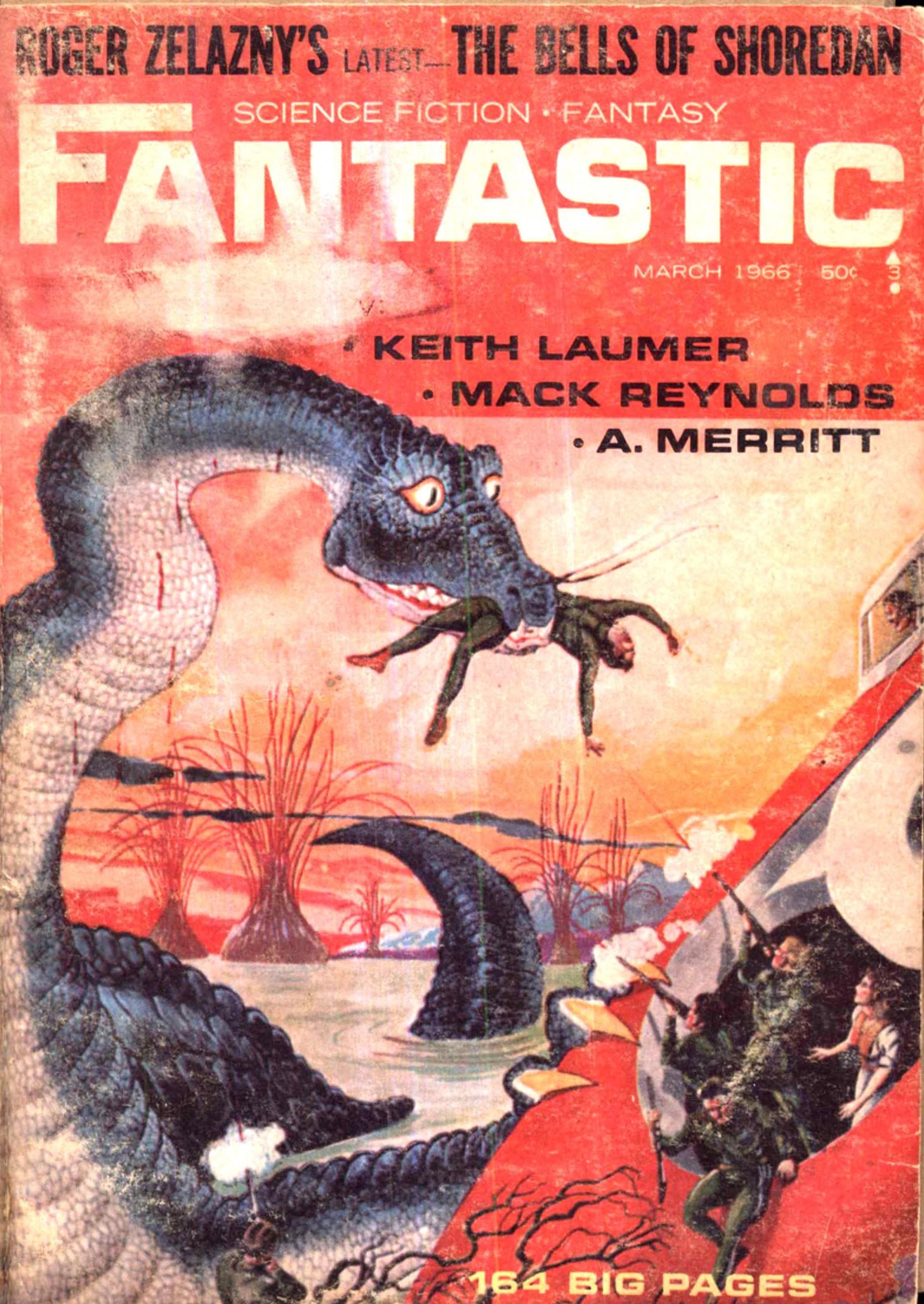

Founder's Day, by Keith Laumer

Retief author Keith Laumer departs from comedic satire for a reasonably straight story. In a future borrowed from Harrison's Make Room! Make Room!, the only escape from Earth's 29 billion inhabitants is a five year journey in stasis to Alpha Centauri 3. But what really lies at the end of a grueling journey that includes a savage boot camp and the stripping away of all humanity?

A competent piece, Founder's Day nevertheless is no more than that. This story of friction between colonist and transport crew could have been set in 19th Century Australia as well as space. Laumer doesn't really bring anything new, in concept or execution.

Three stars.

The Plot is the Thing, by Robert Bloch

Psycho author Robert Bloch doesn't do much fantasy these days, but his turns are always slickly done. In this vignette, young heiress Peggy is the portrait of disassociation, abandoning reality for the Late Show, the Late Late Show, and the All Night Show — any program that will give her the horror flicks she craves. But when drastic medical intervention rescues her at the brink of death, is it salvation, or merely the gateway to greater unreality?

No surprises but the usual excellent execution.

Four stars.

by Gahan Wilson

Experiment in Autobiography, by Ron Goulart

The best part of Goulart's latest story is the double-meaning in the title. One gets the impression that the absurd lengths to which the protagonist, a free-lance writer, must go to collect his ghosting fee, is only slightly removed from reality.

Three stars for Goulart fans; knock one off for everyone else.

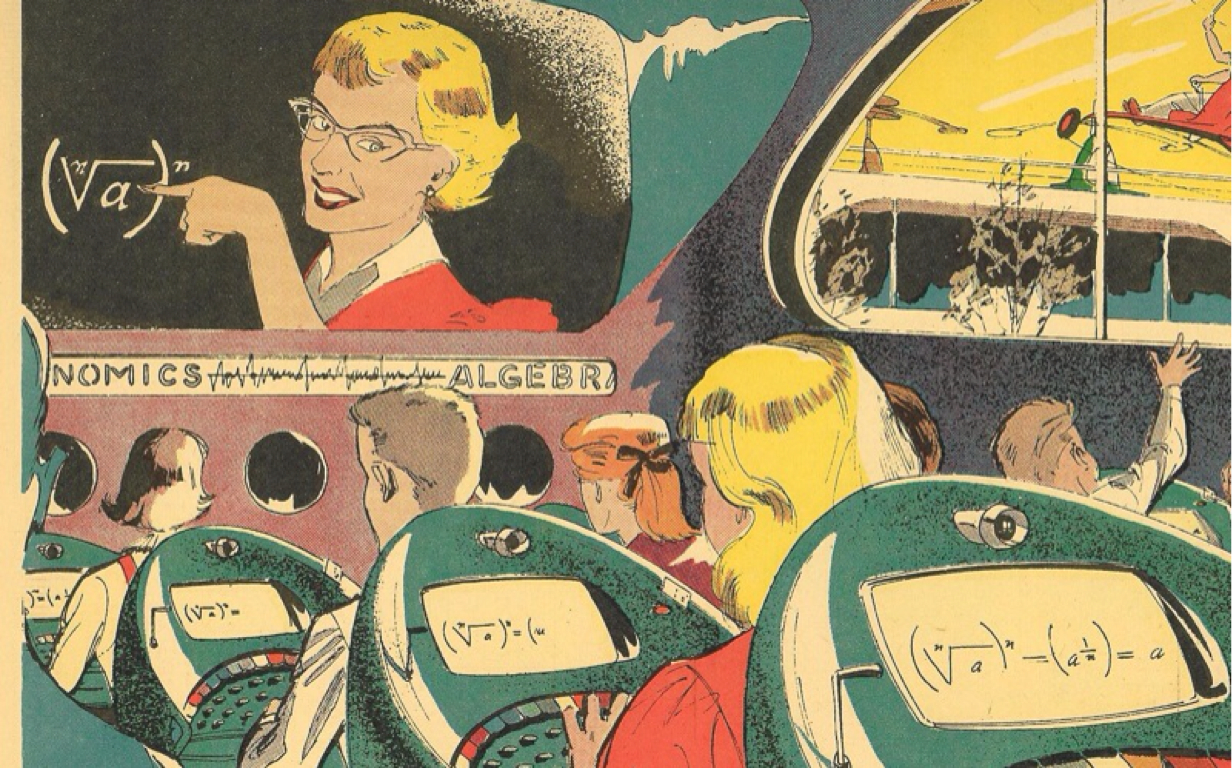

Brain Bank, by Ardrey Marshall

Sturm is a brilliant mathematician cut down in the prime of his life. Too valuable to be left to molder, Sturm is brought back as a disembodied brain, forced to offer his expertise to all who request it: students, businessmen, colleagues. He is a true slave with no human rights and the fear of being switched off perpetually hanging over him. Especially when an old rival, now a tenured professor who made his reputation by stealing the work of his T.A.s and associates, becomes Sturm's latest client.

In setup, it's not unlike Calvin Demmon's vignette The Switch, which appeared in F&SF last year. But the execution here is breezy, the story more of a potboiler.

I don't know if I buy the premise, but I can easily imagine a much put-upon sentient computer in the same situation. The rather conventional adventure story overlies some thoughtful philosophy.

Three stars.

Man in the Sea, by Theodore L. Thomas

Is oxygenated water the solution to problems posed by deep sea diving? What about direct oxygenization of blood? Some neat ideas that I can't immediately poke holes in for once.

Four stars.

The Age of Invention, by Norman Spinrad

This flip piece posits that our current art culture, and the ease with which it is manipulated, is no new thing at all. Indeed, it's been with us since we've been recognizably human.

Fun fluff. Three stars.

Balancing the Books, by Isaac Asimov

The latest article from The Good Doctor is about conservation of charge and mass in the subatomic particles. I suspect the material could have been covered in a piece as short as Thomas' column. Padded to ten pages, it loses its punch.

Three stars.

Revolt of the Potato Picker, by Herb Lehrman

A spud farmer, one of the last dirt agriculturalists in a time of yeast and lichen hydroponics, buys a sentient tractor to do his harvesting. All is well until the robot's sensitive side comes to the fore. Instead of devoting its (her?) time to picking and peeling, all it (she?) wants to do is pursue artistic interests.

Meant to be a winking, nudging joke of a story, I found it both distasteful and also just kind of stupid.

Two stars.

The Manse of Iucounu, by Jack Vance

At last, the meanderings of Cugel the Clever come to a close. Banished to the ends of the Dying Earth by Iucounu, the mage he was trying to rob, Cugel at last finds a way home with the treasure he was sent to find. The key turns out to be a misadventure with sapient rats and a liaison with a sorcerer liberated from their clutches.

Like the rest of the series, it wobbles between wittily imaginative and routine, too episodic to really engage. If anything, it feels like a modern day, rather adult Oz story. With a thoroughly unpleasant though sometimes entertaining antihero.

Call it four stars for this entry and three and a half for the series as a whole.

Emerging from Solace

There are issues of F&SF that astound, leaving an indelible impression. There have been others (not recently) that are better left to gather dust on the shelf (if not utilized for kindling next winter). The July 1966 issue lies on neither extreme. But if you find yourself wanting a quiet weekend away from the strife of the real world, this issue will be a fine companion.

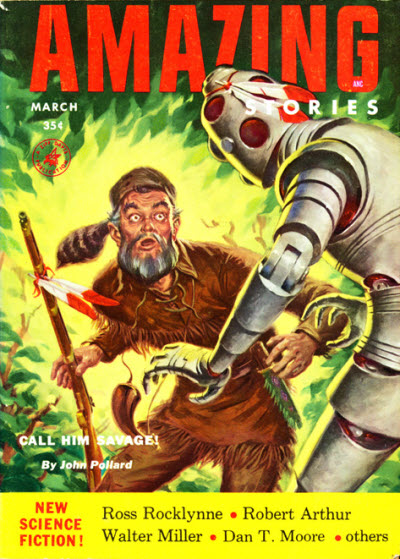

![[June 16, 1966] Calm Spots (July 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/660616cover-672x372.jpg)

![[June 2, 1966] Bad Decisions (July 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/IF-1966-07-Cover-654x372.jpg)

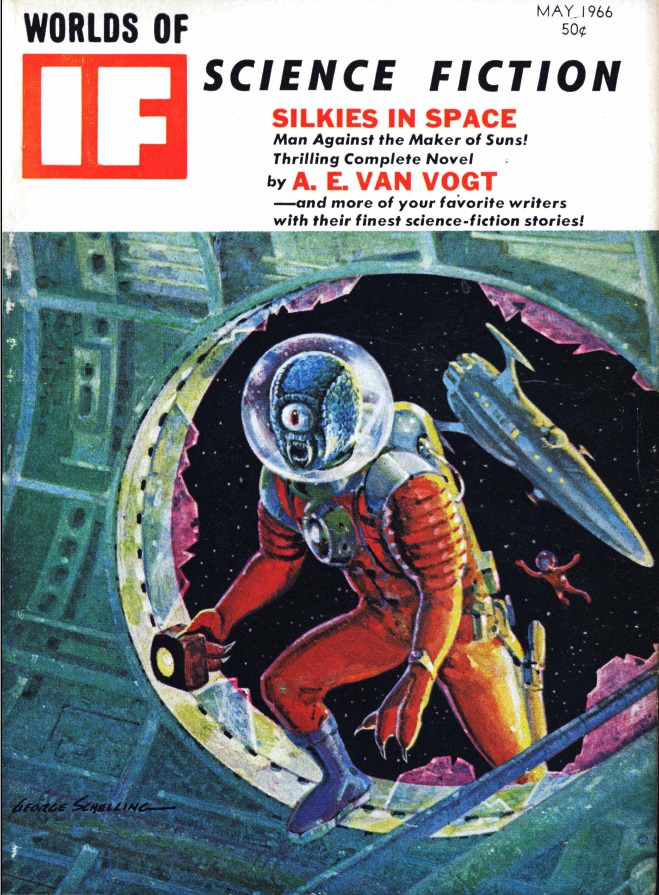

![[May 2, 1966] By Any Other Name (June 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/IF-1966-06-Cover-650x372.jpg)

![[April 2, 1966] Hidden Truths (May 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/IF-1966-05-Cover-659x372.jpg)

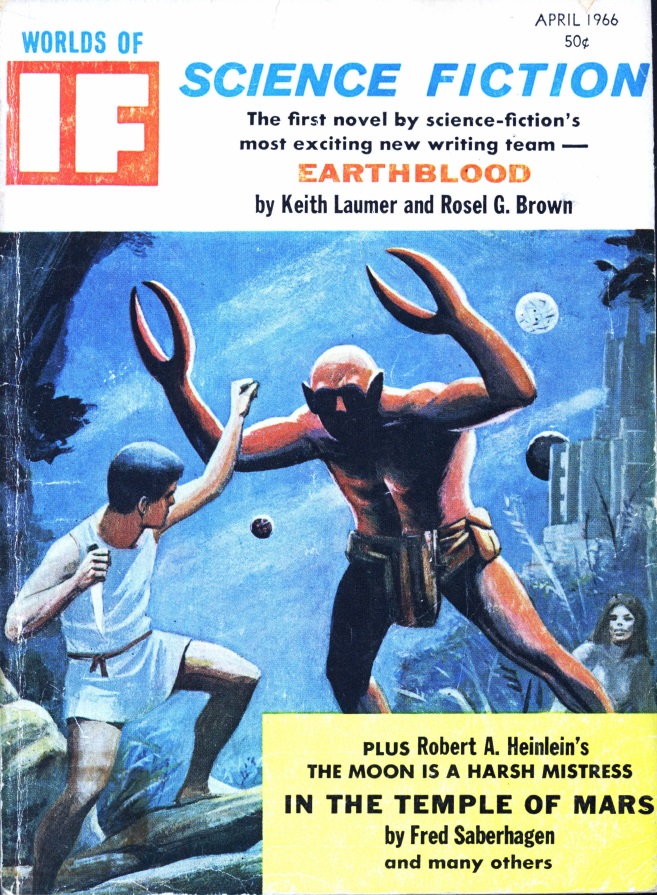

![[March 2, 1966] Words and Pictures (April 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/IF-1966-03-Cover-1-657x372.jpg)

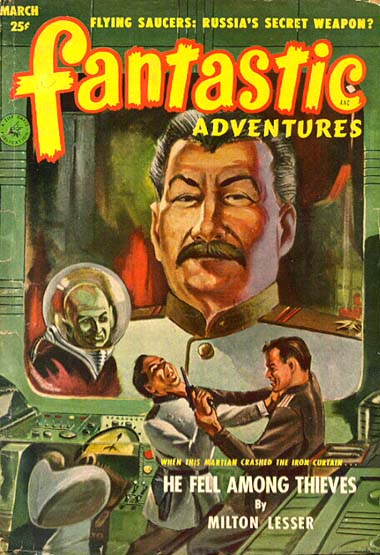

![[February 12, 1966] Past? Imperfect. Future? Tense. (March 1966 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Fantastic_v15n04_1966-03_0000-3-672x372.jpg)

![[February 8, 1966] Feeling A Draft (March 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/IF-1966-03-Cover-641x372.jpg)

![[December 14, 1965] Expect the Unexpected (January 1966 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Fantastic_v15n03_1966-01_0000-3-672x372.jpg)

![[November 2, 1965] Revolution! (December 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/IF-1965-12-Cover-652x372.jpg)