by David Levinson

[L]et us to the end dare to do our duty as we understand it.

– Abraham Lincoln, Address to the Wisconsin State Agricultural Society

A duty to a higher power

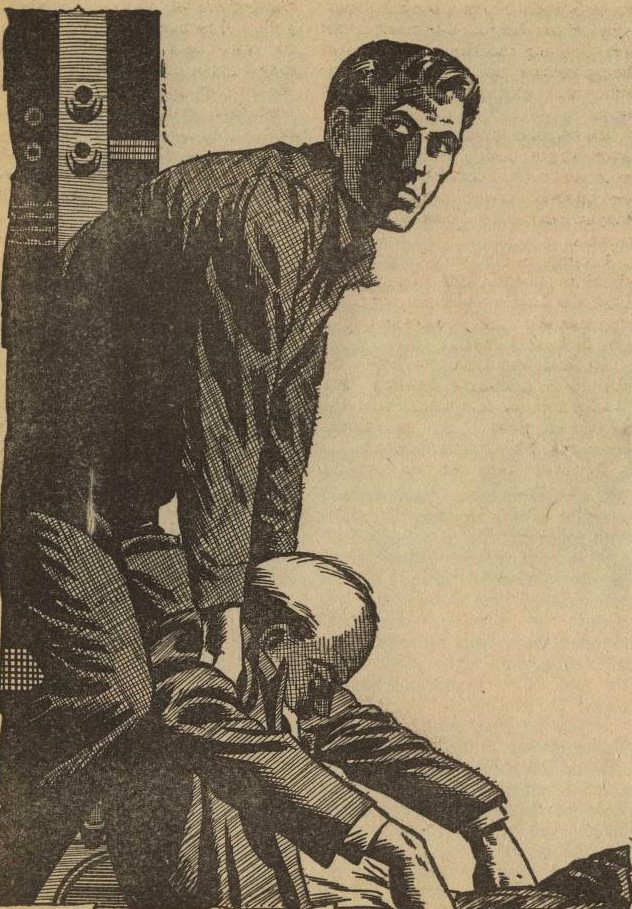

On April 28th, heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali (whom many papers insist on calling by his former name, Cassius Clay) refused induction into the United States Army. In a matter of hours, the New York State Athletic Commission revoked his boxing license, and the World Boxing Association stripped him of his title. For those paying attention, Ali’s refusal came as no surprise. He had been classified as 1-Y (fit for service only in times of national emergency) due to his poor performance on the qualifying test, but when the army lowered its standards last year, he became subject to reclassification as 1-A. The draft board in Louisville Kentucky did so, and he appealed, seeking exemption as a Muslim minister (often incorrectly reported as conscientious objector status). The board denied the appeal in January, and Ali vowed to go to court. After moving to Houston, Texas, the champ again sought reclassification and was again denied.

Muhammad Ali is escorted from the induction center in Houston, Texas.

Muhammad Ali is escorted from the induction center in Houston, Texas.

When called up, Ali appeared as ordered at the Houston induction center and participated in all the pre-induction activities. But when called to step forward for induction, he refused. He was taken aside and the consequences were explained, but he once again refused. After that, he signed a statement indicating his refusal and was escorted outside. He didn’t address the reporters and television cameras waiting for him, but handed out copies of a four-page statement indicating that he is aware of the penalties he faces, but that accepting induction is inconsistent with his “consciousness as a Muslim minister and [his] own personal convictions.” The case has been referred to the U. S. Attorney. If convicted, Mr. Ali faces a maximum of 5 years in prison and a $10,000 fine.

A sense of duty

Like Muhammad Ali, almost everyone in this month’s IF is motivated by strong beliefs: their duty to king and country, humanity at large, or their own personal beliefs and obligations.

Uncle Martin and Tim (from My Favorite Martian) seem to have had a falling out. Actually, this is supposedly from Spaceman!

Uncle Martin and Tim (from My Favorite Martian) seem to have had a falling out. Actually, this is supposedly from Spaceman!

Art by Wenzel.

Wizard’s World, by Andre Norton

Hunted for being an Esper, Craike decides death is preferable to capture and hurls himself from a cliff. And finds himself in another world, one where people like him are seen as wizards who maintain order for the feudal lords and will not tolerate unregulated Espers. He soon falls afoul of these Black Hoods by rescuing an attractive young woman who was being punished for being outside of the established system.

Takya and Craike set a trap for the Black Hoods. Art by Gray Morrow

Takya and Craike set a trap for the Black Hoods. Art by Gray Morrow

We’ve all read this story a hundred times. Man from our world or one reasonably close finds himself mysteriously transported to another world, where he uses his knowledge and different way of thinking to upset the bad social order and get the girl. From John Carter to Lord Kalvan, the template has few variations. Norton’s typical strong writing lifts this above the usual fare, but she offers us nothing new. And there are bits that bother me. For all her power and maturity, Takya is clearly meant to be a young teen, who spends the whole story clad only in her hair. Then at the end, the wooing she expects from Craike borders on rape, however consensual it may be.

Three stars, strictly for being well-written.

Berserker’s Prey, by Fred Saberhagen

Gilberto Klee was working on a youth farm when he was captured in a berserker raid. Now aboard a human ship converted to berserker use, he meets other prisoners, one of whom is sure he can fly the ship if only they can destroy the berserker brain piloting it. Because human captives are suffering from dietary deficiencies, the berserkers order Gil to grow something to end the problem. He suggests a fast-growing squash, though the others disdain him for aiding their captors. Is Gil trying to be viewed as “goodlife” or is there something else going on?

As fellow Journey writer Victoria Silverwolf recently noted, Saberhagen is able to return to this setting over and over again without repeating himself. Perhaps that’s because most of these stories, like this one, tend to be character pieces with the action secondary to the plot. The tight focus on Gil’s internal thoughts without giving away the ending is extremely well done. The ending is also quite symbolic for the overall struggle against the great killing machines.

A very high three stars.

All True Believers, by Howard L. Morris

Not quite two years after thwarting the invasion of Briden by the Freunch under Naflon (see Not by Sea), Sir Hubert Wulf-Leigh (Wilfly) stumbles upon a new Freunch plot: a simultaneous rising in Cullenland and a landing by the Pantlerist pretender in Celtland. Once again, his brilliant mind – aided by a regrettable lack of wine – is up to the challenge.

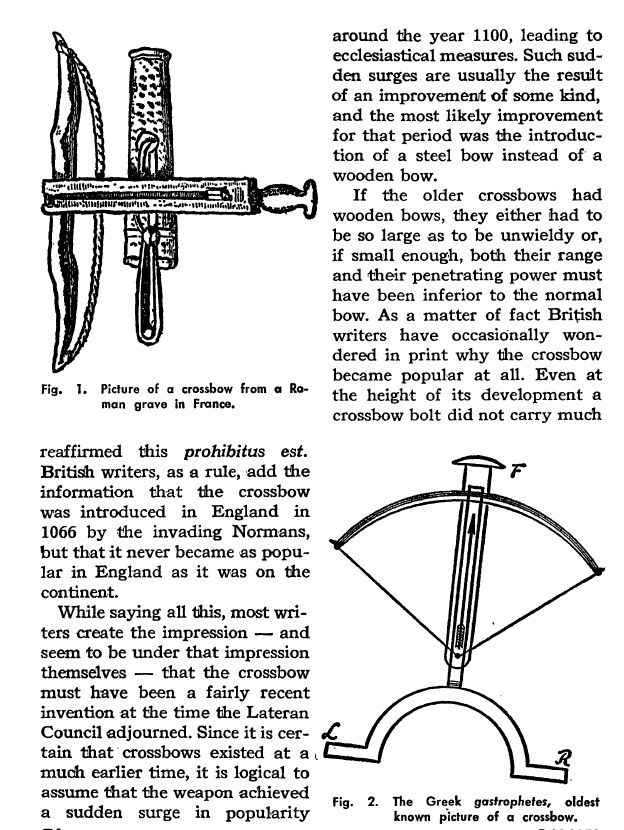

A strand-gleaner makes an important discovery. Art by Virgil Finlay

A strand-gleaner makes an important discovery. Art by Virgil Finlay

The previous story by this author, though readable, was a little too long and tried much too hard to be funny. Morris has largely corrected those problems, though he’s stuck with the ridiculous place names. This piece is clearly based on British fears during the Napoleonic Wars of an Irish rebellion and an attempt by the Stewart pretender to claim the throne and is really no more plausible here than it was in reality. Also the Finlay art seems to be repurposed from Treasure Island or something and doesn’t fit at all. Still, it's all an improvement.

Three stars.

The N3F and Others, by Lin Carter

After looking at a number of less successful attempts at creating national fan clubs last month, Carter looks first at the strange story of the Cosmic Circle and then the more successful National Fantasy Fan Federation. The N3F has lasted a quarter century at this point, but Carter seems ambivalent. In his opinion, it and its extensive membership list offer a reasonable first step and a way to meet fans near you and around the country, but he feels that the organization doesn’t really do anything in fandom. Nevertheless, it seems to be a good introduction for those without a local club in their vicinity.

Three stars.

The Castaways, by Jack B. Lawson

A handful of people are on their way to Smith’s World in suspended animation aboard an automated spaceship when an unexpected nova sends the ship off course. They’re able to find a habitable world, but it’s one without any other people. Can the end products of 6,000 years of civilization survive in a primitive setting?

While the writing is strong on a line-by-line basis, the story itself is so bleak and pessimistic I can’t bring myself to like it.

A very well-written two stars.

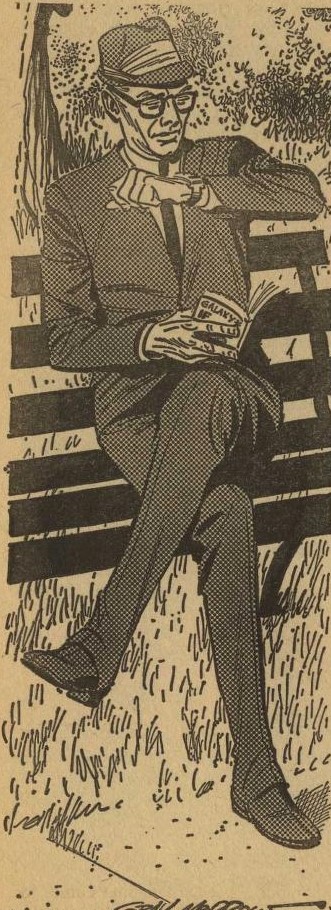

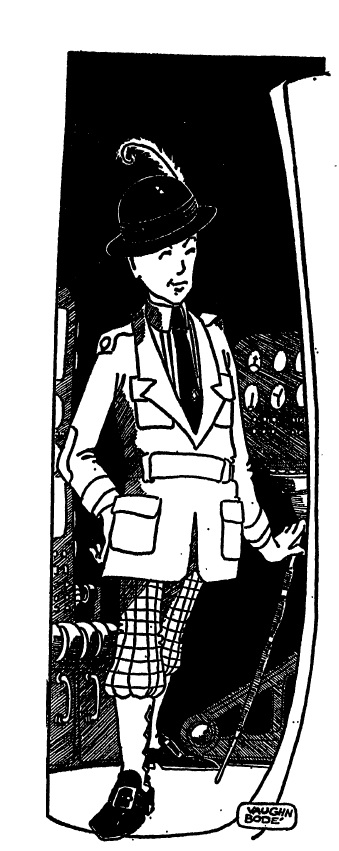

Spaceman! (Part 2 of 3), by Keith Laumer

Seeking shelter from a blizzard, Billy Danger accidentally stowed away on a spaceship, ultimately finding himself marooned with the beautiful Lady Raire and a collie-sized cat named Eureka. Raire was taken away by strange, dwarfish aliens, and Billy had to wait for rescue. Billy then spends a few years working his way up the ladder to Chief Power Engineer and also working his way towards Raire’s home planet near the galactic core. He learns that the aliens who took Raire are known as the H’eeaq. After several (mis)adventures, he finds himself in possession of a stolen spaceship and the assistance of a H’eeaq named Srat.

They begin scouring the scattered worlds of the Galactic Zenith, looking for those who took Raire. On the verge of giving up, he finds Raire enslaved and buys both her and another human. Staggering drunkenly back to his ship after finalizing his purchases, Billy watches as the ship takes off with Raire aboard and then finds himself arrested for illegally manumitting a slave. When he wakes up, he discovers that he has been implanted with a control device. Billy is now a slave. To be concluded.

Billy meets Srat for the first time. Poor Srat. Art by Castellon

Billy meets Srat for the first time. Poor Srat. Art by Castellon

This installment reminded me a lot of Earthblood, especially the protagonist rising through the ranks as he travels and moves ever closer to a seemingly impossible goal. While Rosel George Brown’s steadying influence there gave us moments of introspection, Laumer alone is free to indulge in wild adventure and action. He also has a tendency to rely too much on coincidence to move the plot along. It’s still an enjoyable read, though.

Three stars.

Family Loyalty, by Stan Elliott

A series of letters between Joe Seaworthy, who is emigrating off-world, and his cousin and former employee Harry Aimes, who senses a chance to get himself out of a bind.

Here is this month’s new author. The first letter feels very unnatural, although there are reasons for that. Things improve after that, and Elliott does a pretty good job of telling us a lot about the world without direct exposition.

A low three stars.

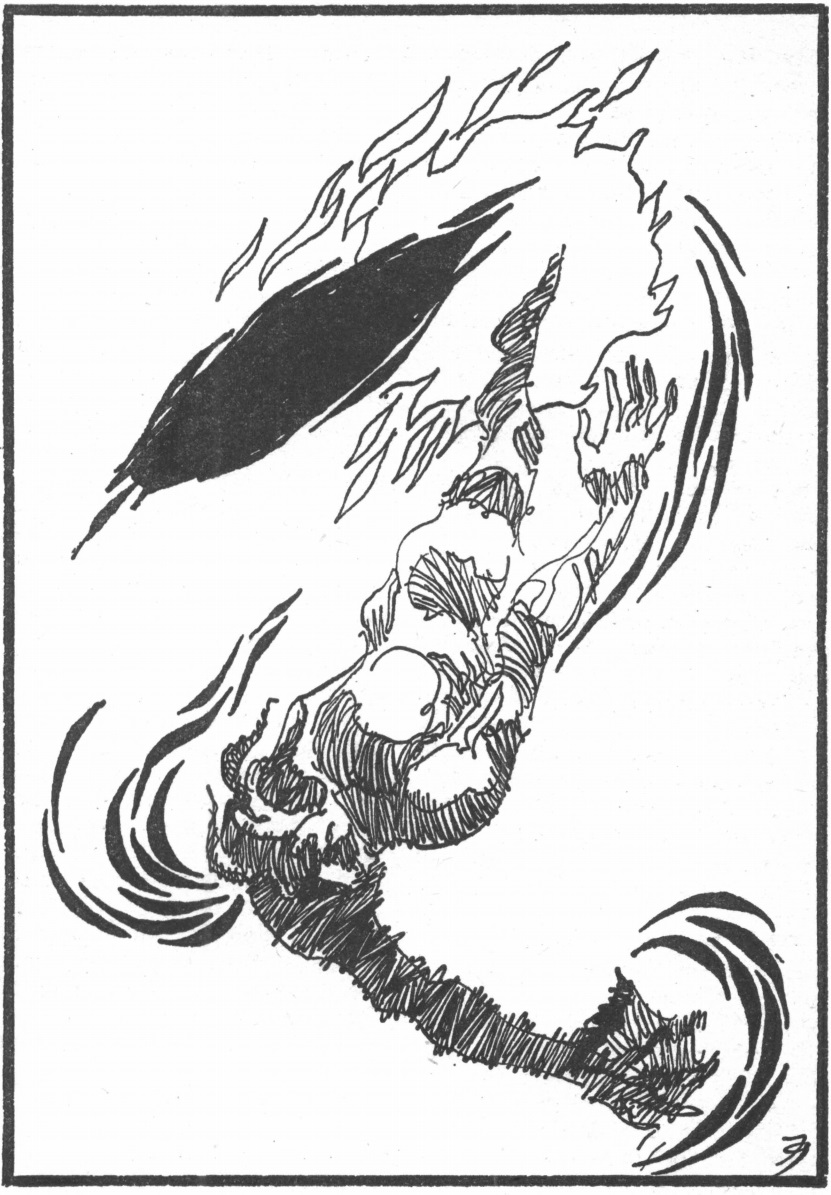

Driftglass, by Samuel R. Delany

Cal Svenson is an amphiman, someone who has been surgically altered so that they can live and breathe underwater. Eighteen years ago, he was severely injured while trying to lay a power cable in an oceanic trench known as the Slash. Unable to work due to a paralyzed leg and torn swim membranes, he has a pension and a house on the Brazilian coast provided by the company he worked for. He spends his days searching for driftglass (also called sea glass) and chatting with his friend Juao, a local fisherman. Encountering a young amphiman woman, Cal learns that the company is planning to try laying a cable in the Slash again the next day. Juao’s two children, Cal’s godchildren, have been accepted into the amphiman program and must leave for Brasilia the next day as well. Cal has to sort out his feelings about both of these things and their consequences.

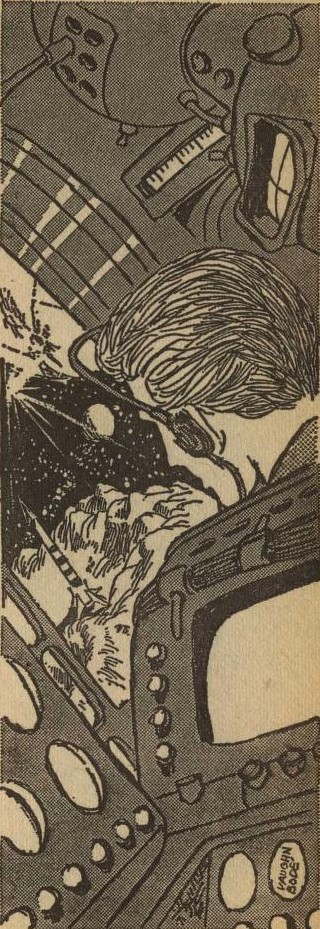

Cal is injured. Art by Gaughan

Cal is injured. Art by Gaughan

Simple. Beautiful. Subtle. Delany writes with a maturity far beyond his 25 years. This story alone is worth your 50¢.

Five stars.

An example of some sea glass

An example of some sea glass

Summing up

That’s another month in the books. Mostly fair to middlin’, but two of the shorter works stand out. The Saberhagen is very good, even if it doesn’t quite deserve a fourth star, and Driftglass is amazing. I expect to see it on all the awards lists. I’m nominating it for a Galactic Star right now, with not even half the year gone.

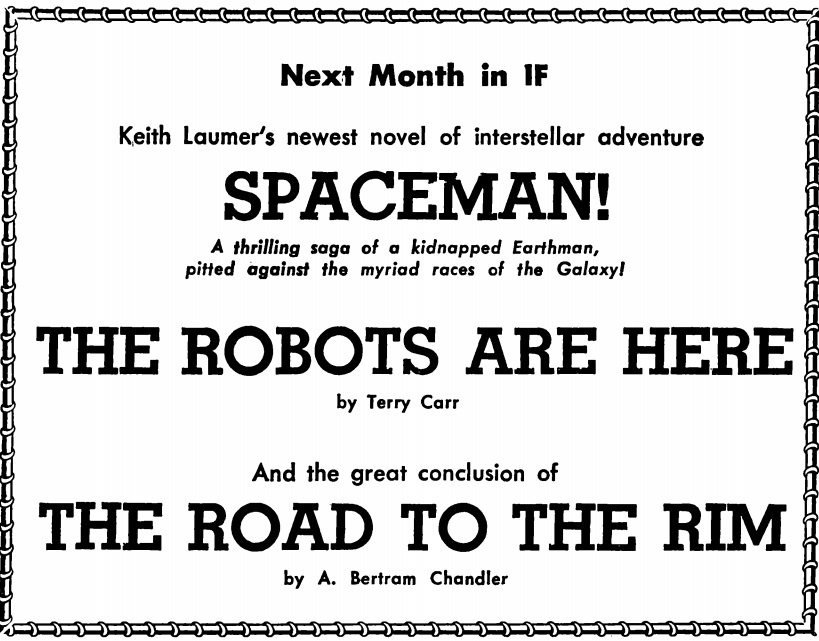

This is presumably the Riverworld story promised for Worlds of Tomorrow. The lack of other information suggests that Fred is scrambling to deal with the loss of a magazine.

This is presumably the Riverworld story promised for Worlds of Tomorrow. The lack of other information suggests that Fred is scrambling to deal with the loss of a magazine.

![[May 2, 1967] The Call of Duty (June 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/IF-Cover-1967-06-672x372.jpg)

![[April 14, 1967] Earth, Air, Fire, and Water (April 1967 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/670414covers-672x372.jpg)

![[April 8, 1967] Swan Songs (May 1967 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v04n04_1967-05_0000-2-672x372.jpg)

![[April 4, 1967] Transitions (May 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/IF-Cover-1967-05-672x372.jpg)

What are these robots up to? Art by Gaughan

What are these robots up to? Art by Gaughan

![[March 4, 1967] Mediocrities (April 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/IF-Cover-1967-03-672x372.jpg)

![[February 20, 1967] To Ashes (March <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/670220cover-661x372.jpg)

![[February 4, 1967] The Sweet (?) New Style (March 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/IF-Cover-1967-02-full-672x372.jpg)

![[January 16, 1967] Off to a Good Start (February 1967 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v04n03_1967-02_0000-2-672x372.jpg)

![[January 10, 1967] Return to sender (February 1967 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/670110cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 2, 1967] Different perspectives (February 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/IF-Cover-1967-01-672x372.jpg)