by David Levinson

Counting coups

March saw not one, but two attempts to overthrow the established government in smaller countries. One failed, but the other looks like it may have succeeded.

Cyprus is the island south of Turkey, west of Syria, north of Egypt

Cyprus is a troubled nation. The populace is divided between those of Greek and Turkish decent, and the long-running hostility between Greece and Turkey spilled over to Cyprus. When the island sought independence from the United Kingdom, Greek Cypriots hoped for eventual union with Greece, which was not acceptable to Turkish Cypriots. The British were able to block annexation (or enosis, as it is called in Cyprus) as a condition for independence, but relationships within the island are so rocky that UN peacekeepers had to be brought in to keep the two populations from each other’s throats.

A major figure in the independence movement was Orthodox Archbishop Makarios III, who has led the country ever since. Before independence, he was a strong supporter of enosis, but was persuaded to accept that it would have to be put off as a hoped for future event. Makarios isn’t terribly popular with western leaders; he’s been a major voice in the Non-aligned Movement. Some in Washington have taken to calling him “the Castro of the Mediterranean.” In the last few years, he’s made himself unpopular at home as well. He’s taken away guarantees of Turkish representation in government and has also moved away from the idea of enosis. His justification is the Greek military coup of 1967, stating that joining Cyprus to Greece under a dictatorship would be a disservice to all Cypriots.

Archbishop Makarios III visiting the Greek royal family in exile in Rome earlier this year.

Archbishop Makarios III visiting the Greek royal family in exile in Rome earlier this year.

On March 8th, somebody tried to kill Makarios. His helicopter was brought down by withering, high-powered fire. Makarios was uninjured, but the pilot was severely wounded. Fortunately, nobody else was on board. At least 11 people have been arrested, all of Greek heritage and strong supporters of enosis. Given the military nature of the weapons used, some are also accusing the Greek Junta of involvement.

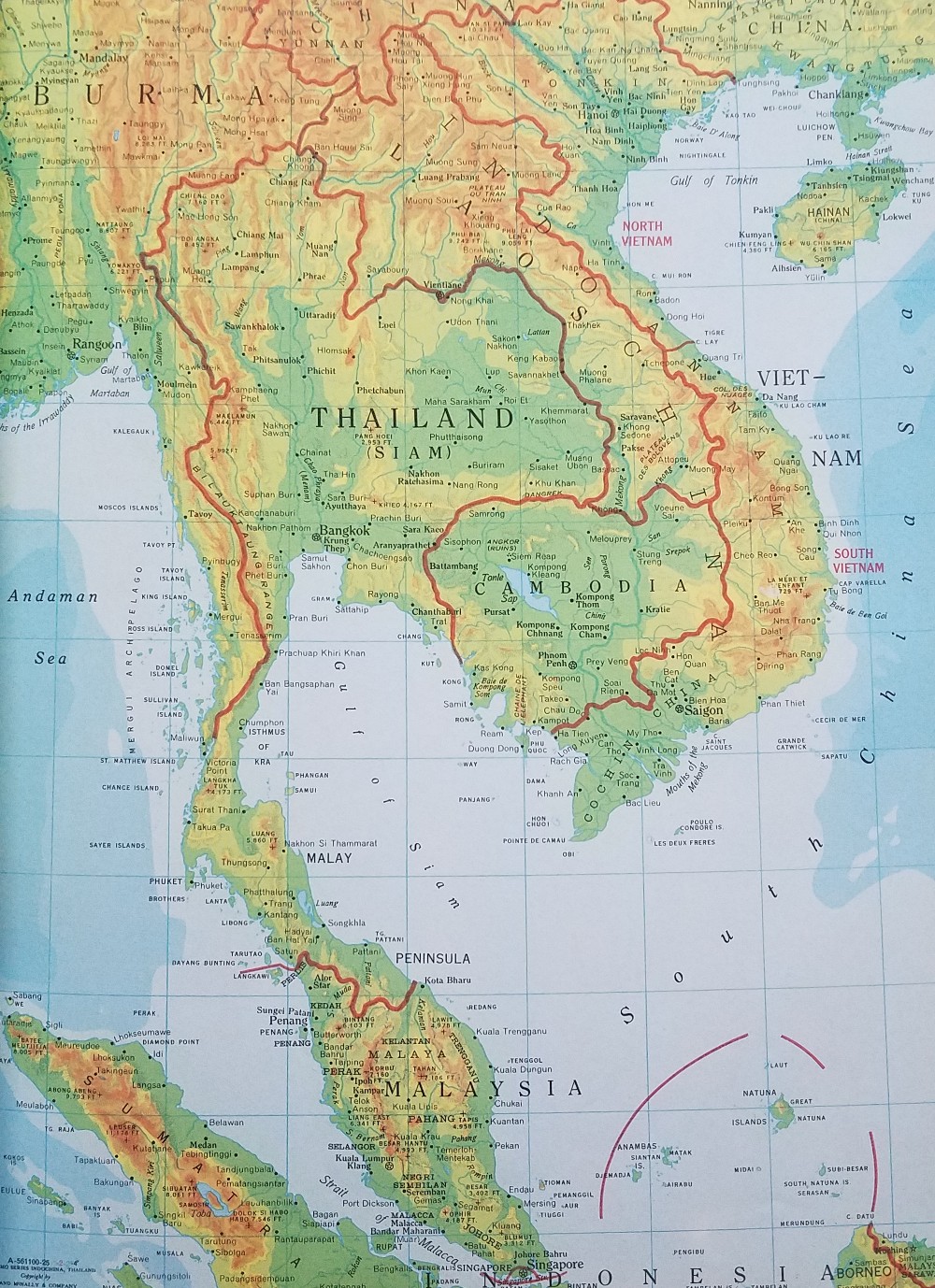

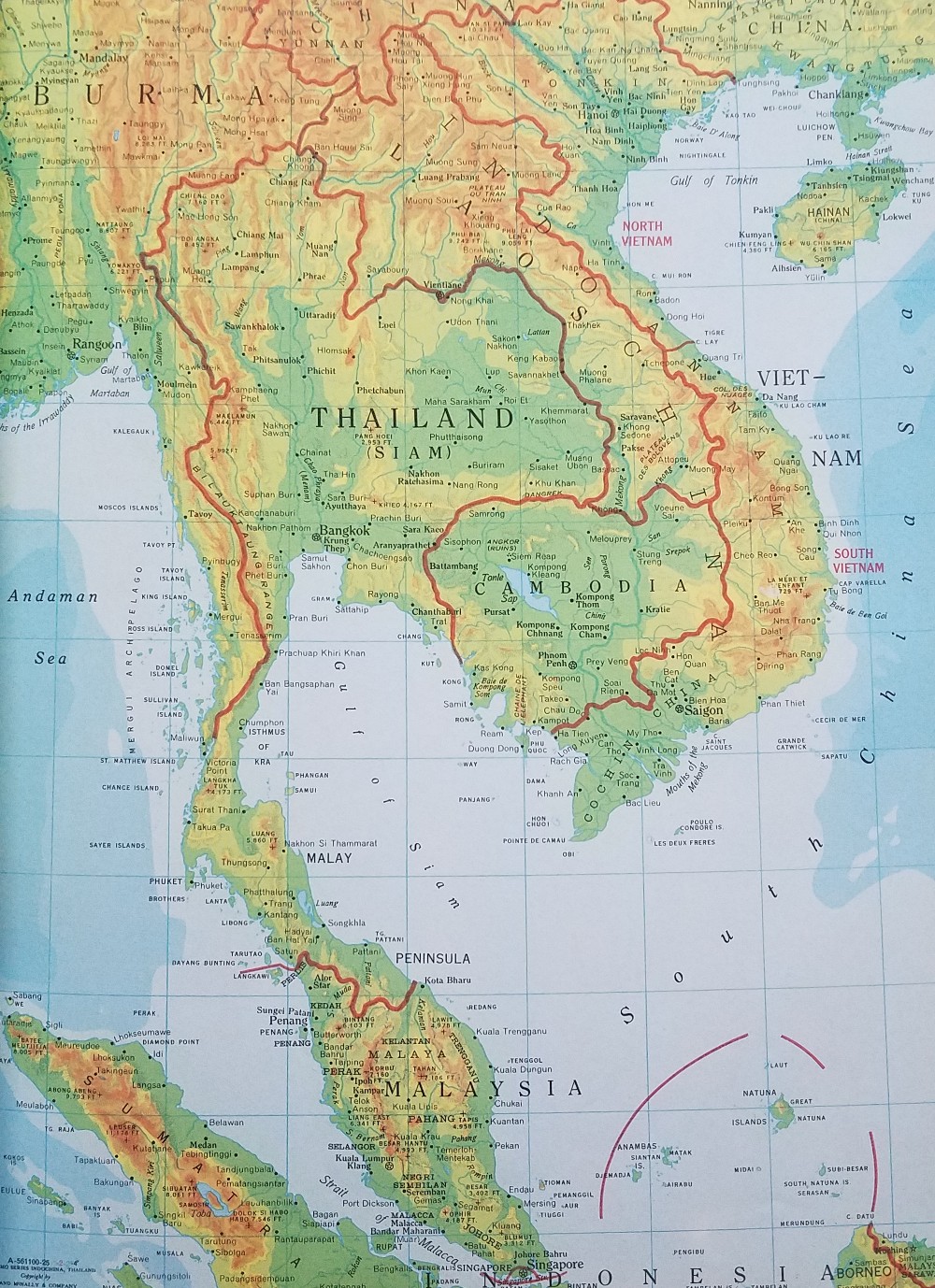

Meanwhile in south-east Asia, Prince Norodom Sihanouk is out as the leader of Cambodia. Like Makarios, he hasn’t been popular in the west, due to his cozy relations with both the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China. He’s also allowed Cambodian ports to be used for bringing in supplies for the North Vietnamese army and the Viet Cong, while also ignoring the use of Cambodian territory as part of the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Sihanouk was out of the country when anti-North Vietnamese riots erupted both in the east of the country and in Phnom Penh. Things quickly got out of hand, with the North Vietnamese embassy being sacked. By the 12th, the government canceled trade agreements with North Vietnam, closed the port of Sihanoukville to them, and issued an ultimatum that all North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong forces were to leave the country within 72 hours. When the demand wasn’t met, 30,000 protesters rallied outside the National Assembly against the Vietnamese.

On the 18th, The Assembly met and voted unanimously (except for one member who walked out in protest) to depose Sihanouk as the head of state. Prime Minister Lon Nol has assumed the head-of-state powers on an emergency basis. On the 23rd, Sihanouk, speaking by radio from Peking, called for an uprising against Lon Nol, and large demonstrations followed. A few days later, two National Assembly deputies were killed by the protesters. The demonstrations were then put down with extreme violence.

l: Prince Sihanouk in Paris shortly before his ouster. R: Prime Minister Lon Nol.

l: Prince Sihanouk in Paris shortly before his ouster. R: Prime Minister Lon Nol.

Where this will lead is anybody’s guess. The new government (it should be noted that the removal of Sihanouk appears to have been completely legal) has clearly abandoned the policy of neutrality and threatened North Vietnam with military action. Hanoi isn’t going to take that lying down; if the war spreads to Cambodia, will the Nixon administration expand American involvement? Add in Sihanouk urging resistance to Lon Nol and the deep reverence for the royal family held by many Cambodians, and it all looks like a recipe for chaos.

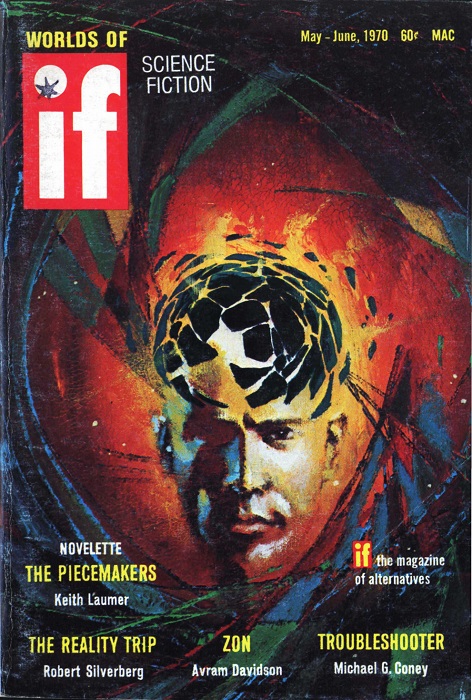

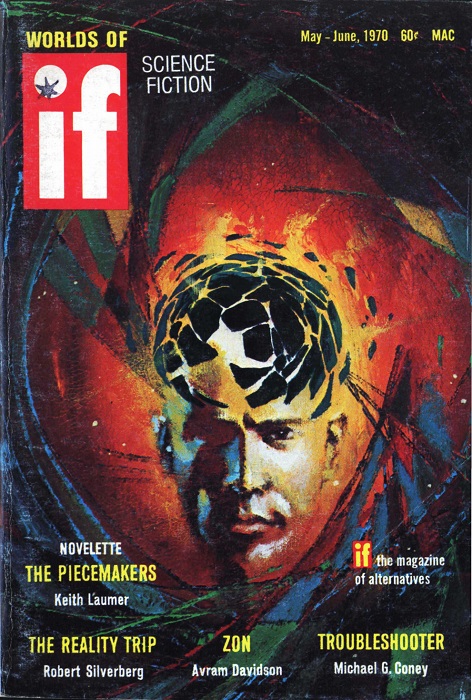

What is man

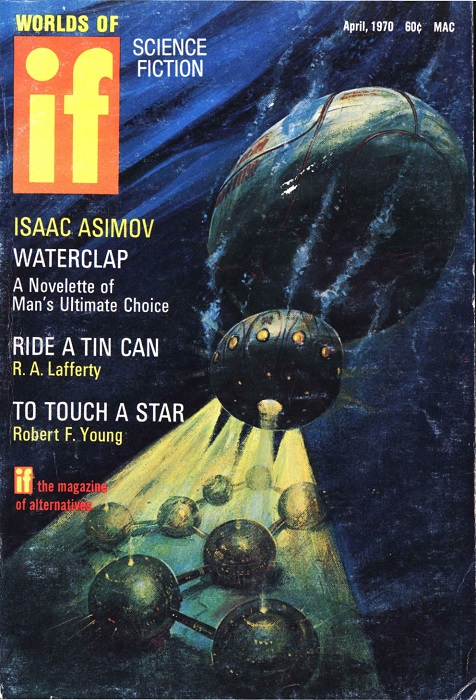

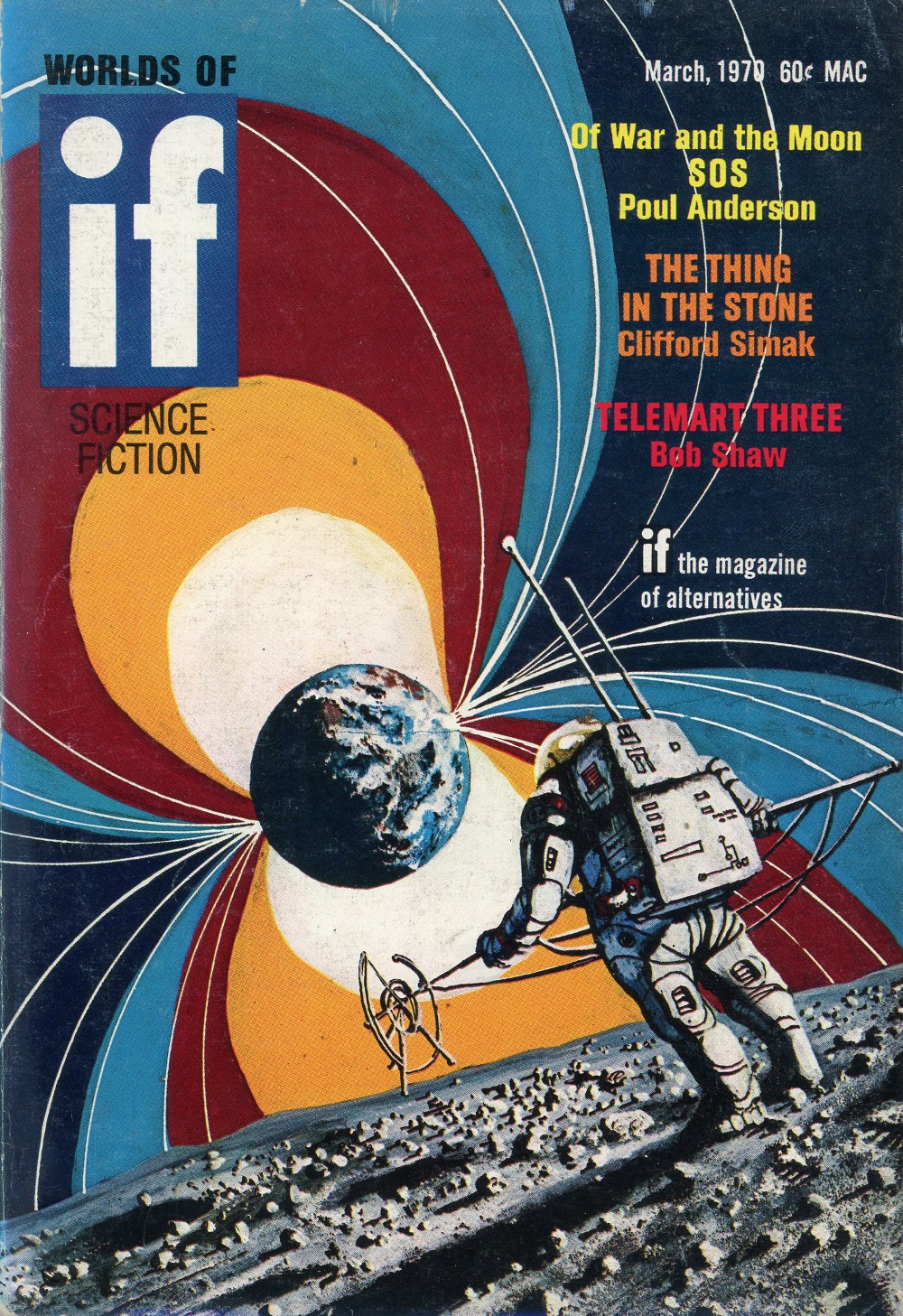

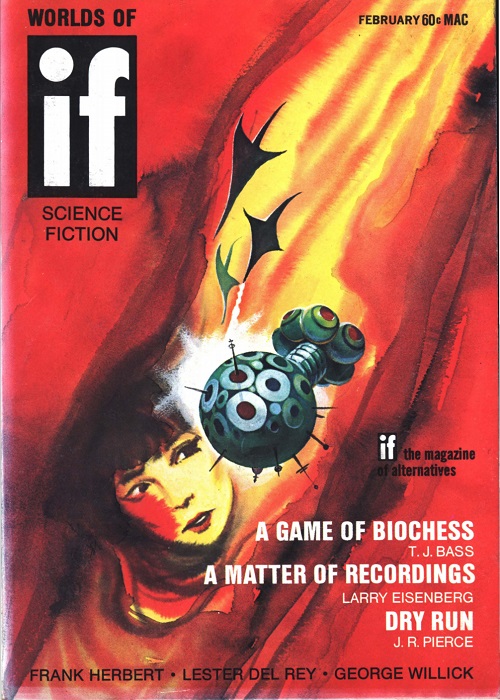

Some of the stories in this month’s IF deal directly or tangentially with what it is that makes humans human. The front cover also raises a question that we don’t have an answer to. We’ll get to that at the end; let’s look at the issue first.

Suggested by Troubleshooter. Art by Gaughan

Suggested by Troubleshooter. Art by Gaughan

Continue reading [April 2, 1970] Being Human (May-June 1970 IF) →

![[April 10, 1970] A Style in Treason (May 1970 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/700410galaxycover-651x372.jpg)

![[April 2, 1970] Being Human (May-June 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/IF-1970-05-Cover-472x372.jpg)

Archbishop Makarios III visiting the Greek royal family in exile in Rome earlier this year.

Archbishop Makarios III visiting the Greek royal family in exile in Rome earlier this year.

l: Prince Sihanouk in Paris shortly before his ouster. R: Prime Minister Lon Nol.

l: Prince Sihanouk in Paris shortly before his ouster. R: Prime Minister Lon Nol. Suggested by Troubleshooter. Art by Gaughan

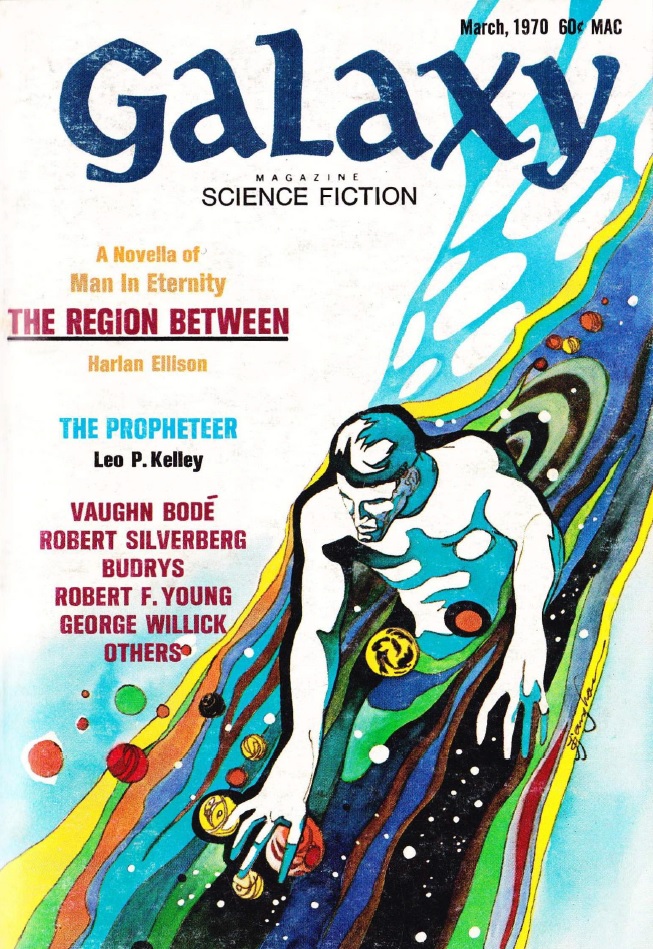

Suggested by Troubleshooter. Art by Gaughan![[March 8, 1970] They say that it's the institution… (April 1970 <i>Galaxy</i> and the incomplete Court)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/700308galaxycover-412x372.jpg)

![[March 2, 1970] Par for the course (April 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/IF-1970-04-Cover-476x372.jpg)

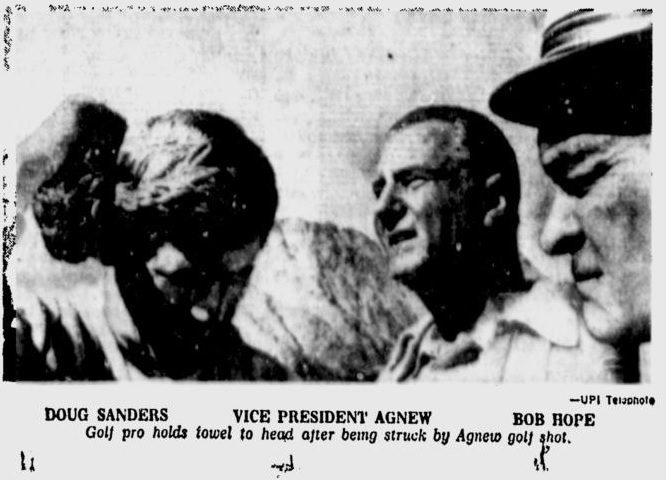

Wire photo of the aftermath.

Wire photo of the aftermath. Arrival at Ocean-Deep. Art for “Waterclap” by Gaughan

Arrival at Ocean-Deep. Art for “Waterclap” by Gaughan![[February 14, 1970] <i>Spock must Die!</i>, <i>Starbreed</i>, <i>Seed of the Dreamers</i>, and <i>The Blind Worm</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/700214covers-672x372.jpg)

![[February 8, 1970] Boldly going to the Region Between (March 1970 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/700208galaxycover-653x372.jpg)

![[February 2, 1970] Deceptive Appearances (March 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/IF-1970-03-Cover-479x372.jpg)

The arbiter, an NCR 315.

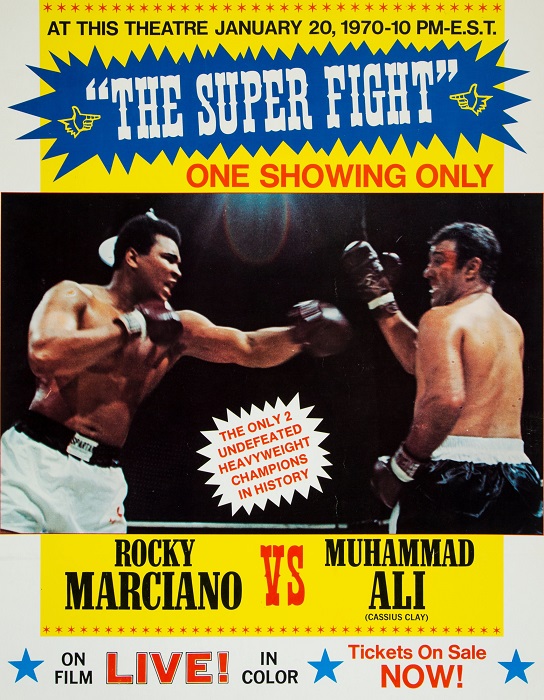

The arbiter, an NCR 315. Movie poster for the event. That “LIVE!” is a little deceptive, which is something else Ali is complaining about.

Movie poster for the event. That “LIVE!” is a little deceptive, which is something else Ali is complaining about. Art actually for “SOS,” rather than just suggested by. Maybe because it’s by Mike Gilbert, not the overworked Jack Gaughan.

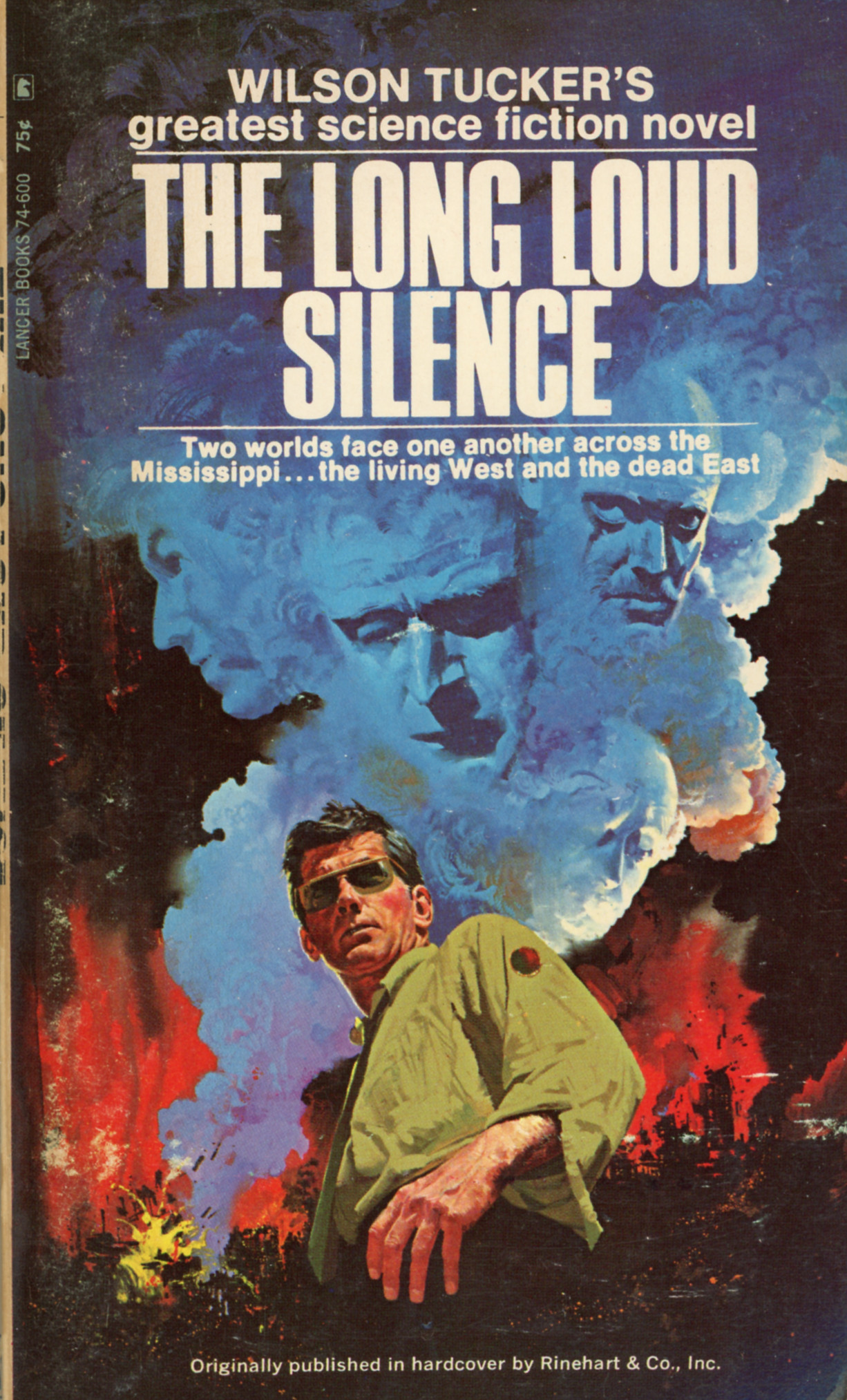

Art actually for “SOS,” rather than just suggested by. Maybe because it’s by Mike Gilbert, not the overworked Jack Gaughan.![[January 18, 1970] Below par (<i>The Long Loud Silence</i>, <i>Sex and the High Command</i>, <i>Beachhead Planet</i>, and <i>Taurus Four</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/700118covers-672x372.jpg)

![[January 8, 1970] Slow Sculpture, Fast reading (the February 1970 <i>Galaxy Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/700108galaxycover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 2, 1970] Under Pressure (February 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IF-1970-02-Cover-500x372.jpg)

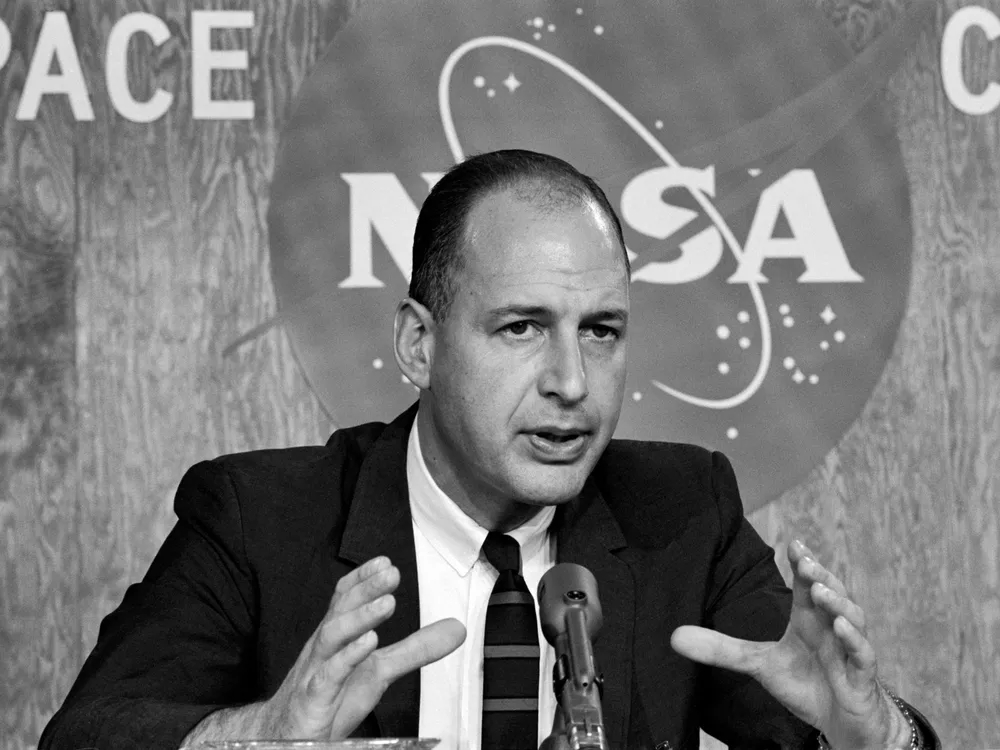

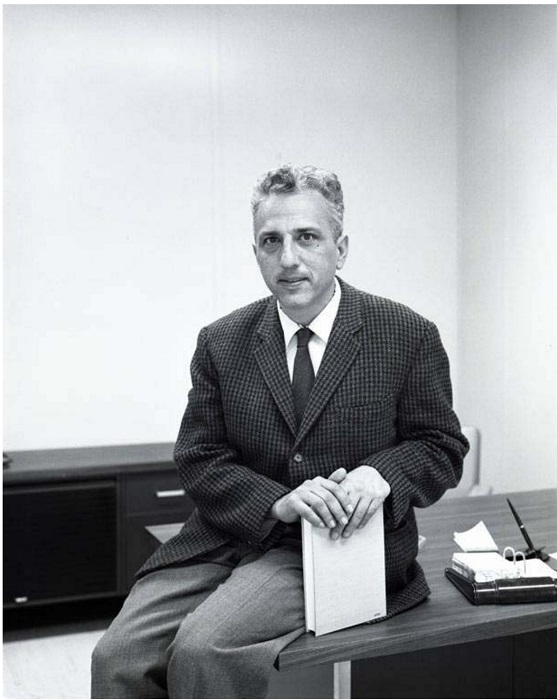

Dr. Edward D. Goldberg of the Scripps Institute of Oceanography in La Jolla, California

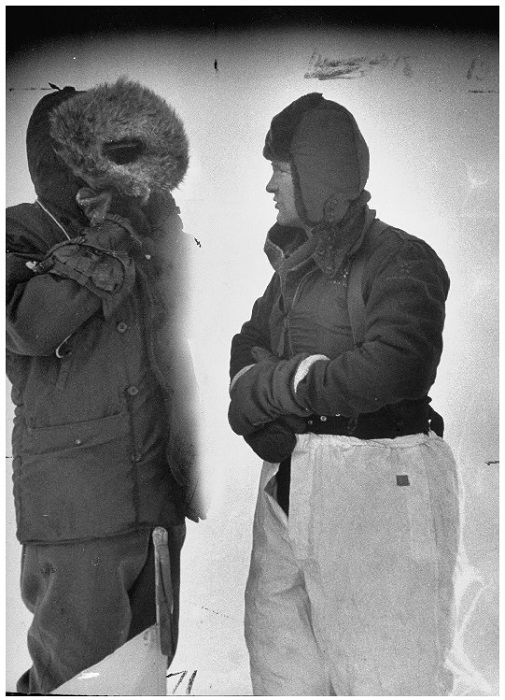

Dr. Edward D. Goldberg of the Scripps Institute of Oceanography in La Jolla, California Col. Fletcher (r.) on his ice island in 1952. This was the most recent photo of him I could find.

Col. Fletcher (r.) on his ice island in 1952. This was the most recent photo of him I could find. Dr. William W. Kellogg of the National Center for Atmospheric Research, in Boulder, Colorado

Dr. William W. Kellogg of the National Center for Atmospheric Research, in Boulder, Colorado Cover by Gaughan. Supposedly suggested by Whipping Star, but it looks more like it illustrates Pressure Vessel to me.

Cover by Gaughan. Supposedly suggested by Whipping Star, but it looks more like it illustrates Pressure Vessel to me.