by Gideon Marcus

Vicious Varangians

Reliving the Middle Ages "as they ought to have been" is all the rage now, from Renaissance Pleasure Faires to The Society for Creative Anachronism to The Byrd's song, "Renaissance Faire". Not to be left out, our corner of San Diego has decided to put on its own Viking Fest, featuring axe-throwing, mead-drinking, and general revelry.

Of course, the seasoned time-traveling Journey crowd attended!

Something to cheer about

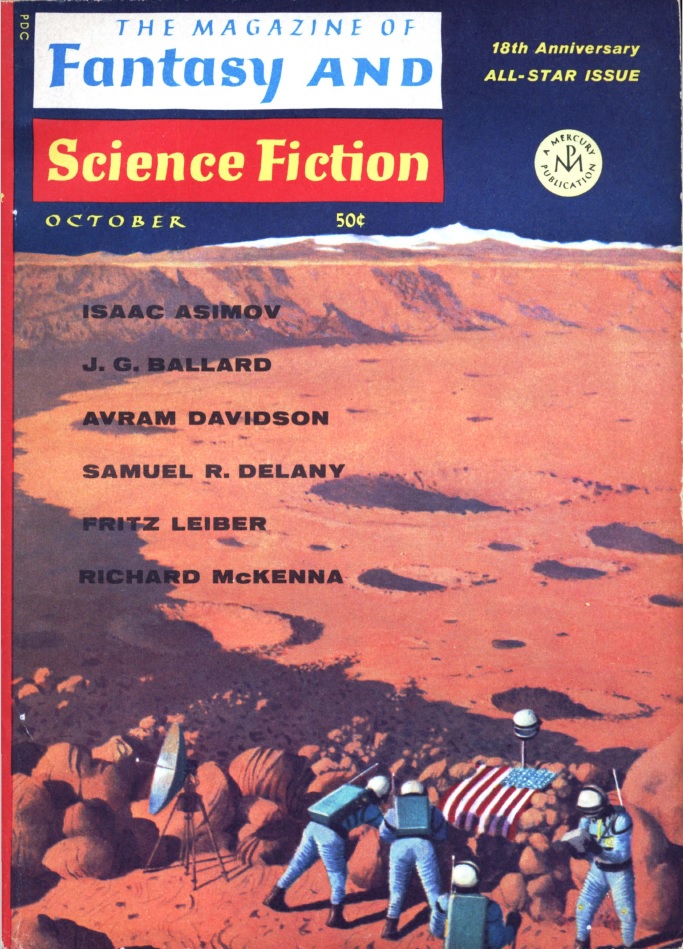

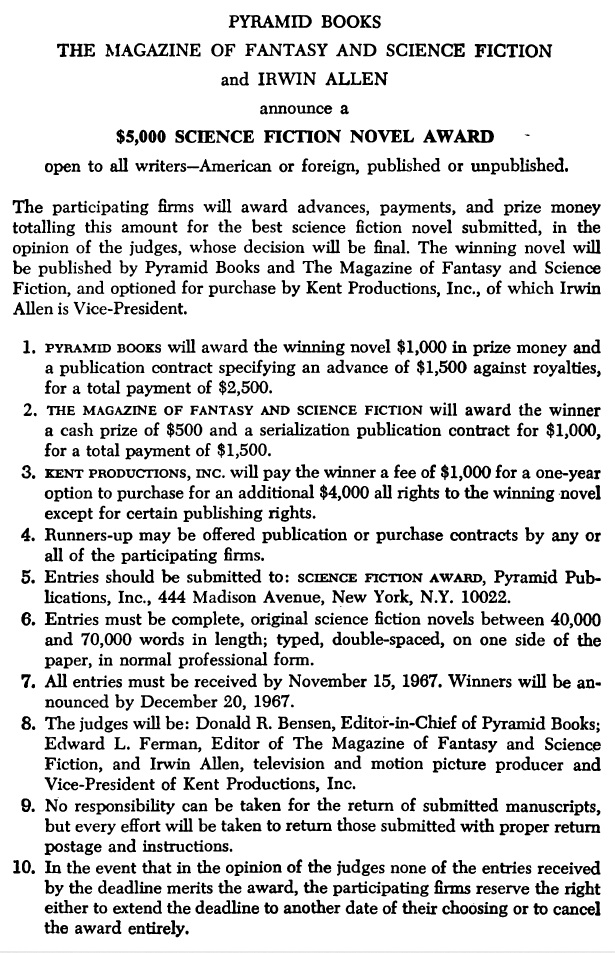

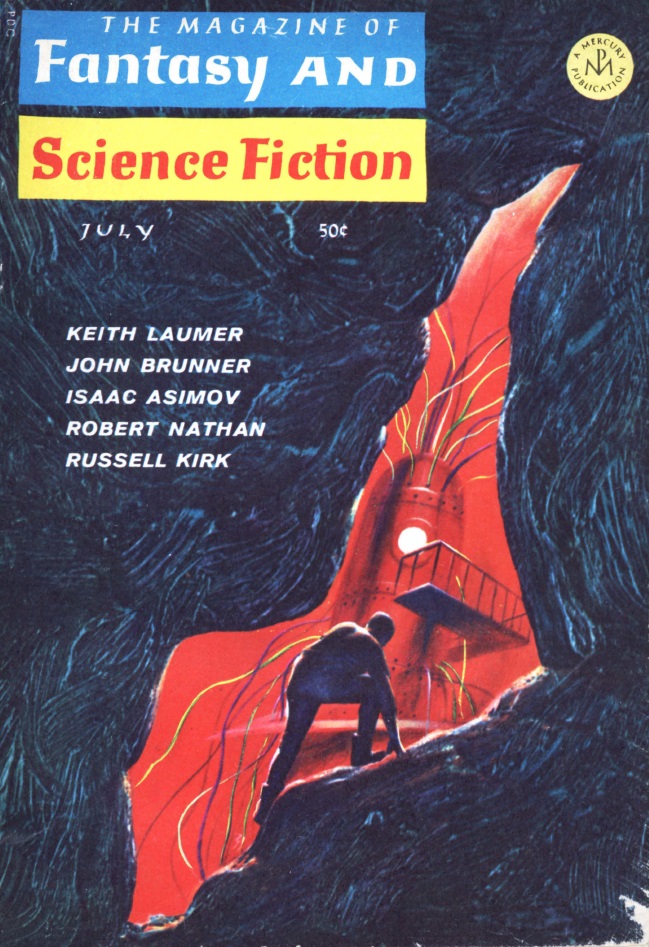

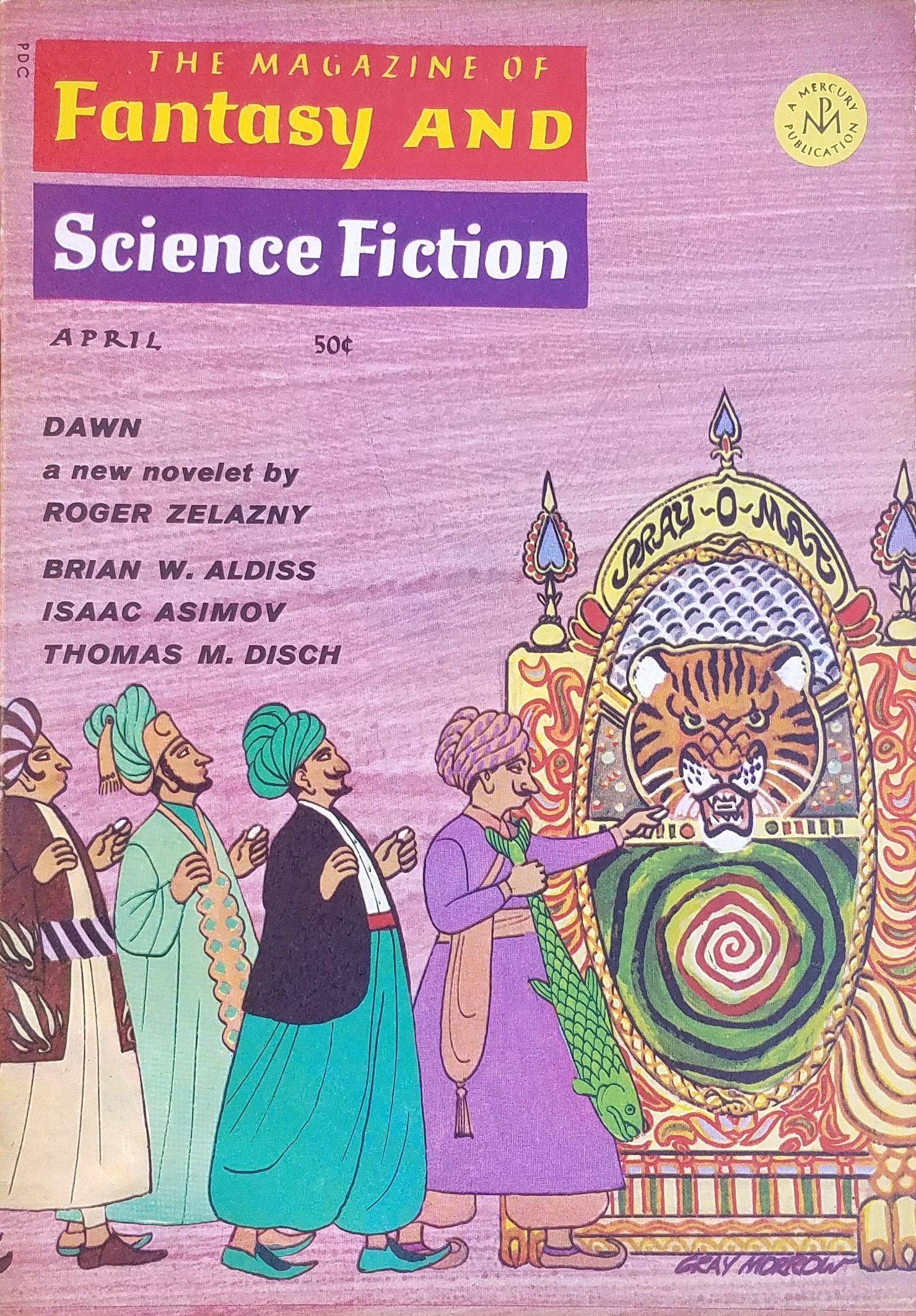

It's been a while since I've been able to report on a issue that's good from bow to stern (recognizing that such things are rare, of course–Sturgeon's Law ensures much of what anyone reads must not be the best). I'm happy to report that this month's issue of Fantasy of Science Fiction was quite enjoyable.

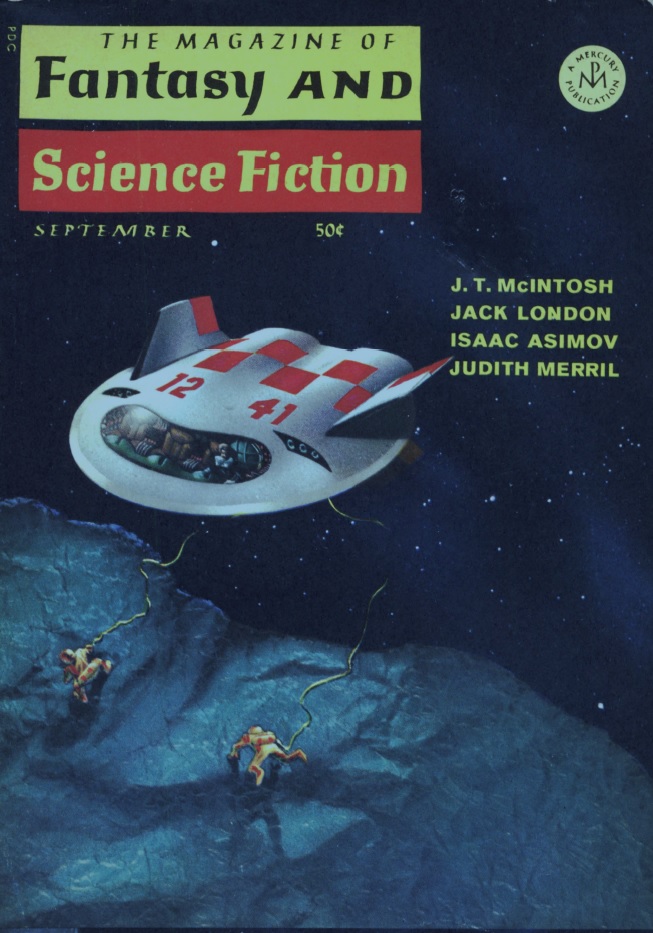

by Chesley Bonestell; as usual, it doesn't illustrate any of the stories inside

Home the Hard Way, by Richard McKenna

Chief Biotech Skinner Webb of the Galactic Patrol Ship Carlyle is determined to jump ship. The why: planet Conover is the loveliest world Webb has ever espied, and its richest denizens have offered him the moon…and a chance at love with a plump and gorgeous scion.

Sadly for Skinner, he's got a seven year hitch. And so, he does his damndest to get out of it, going AWOL, starting fights, even consorting with a criminal element. All it does it lose him stripes and put him under Vry Chalmers, his former adjutant and long-suffering friend. Will Webb ever get to paradise?

Author Richard McKenna seems to write more now that he's dead than he did when he was alive. I quite enjoyed this space-based yarn, and I particularly appreciated the frequent appearance of women in the navy–as high rated enlisted men, no less. I don't think I've ever seen that particular touch in a story. We've had women officers (q.v. Star Trek and Starship Troopers), but no women grunts. Certainly, it's a rare thing.

Of course, as my wife notes, why anyone would fall for Skinner Webb, when he's something of a lummox, is a bit of a mystery. But perhaps we just have an unsympathetic narrator. In any event, this story gets an unreserved four stars.

The Inner Circles, by Fritz Leiber

The artful Leiber offers up this tale of a family that seems to create its own reality. The father molds ebony companions out of shadow, with whom he converses over watered-down martinis. The mother sketches fanciful worlds and imagines that the machines of the house talk to her. And the son is an interstellar rocket jockey, aided by just a few toys as visual aids.

Notable for including the second use of the word "shit" in as many months in F&SF (will the mails stop carrying this trashy publication?) and for a surprising but welcome happy ending, this is another good piece. Leiber, a veteran stage actor, has mastered the art of rendering the theatrical in his prose. Four stars.

Speaking of Leiber…

Camels and Dromedaries, Clem, by R. A. Lafferty

Cleminger is a big man, one of the hottest traveling salesmen in the country. In fact, he's a little too big: one day, he falls asleep in a hotel and splits into two beings–externally identical, but somehow each half a man. The two go on to live separate lives, until their desirable and desiring wife, Veronica, demands an end to the intolerable situation.

Lafferty is always whimsical, but this piece feels a bit more grounded than most–more Ellison than Lafferty. Once again, it's enjoyable from beginning to end. That's three four-star stories in a row!

The Power of Every Root, by Avram Davidson

Now off to sunny Mexico, where Carlos Rodriguez Nunez, police officer of the municipality of Santo Tomas, finds himself increasingly afflicted with physical maladies, as well as furtively derided by his townsfolk. Is it a disease? A hex? The doctor cannot help, and the witch doctor's advice seems spurious. Surely his luscious wife, Lupe, is above suspicion…

Davidson, once editor of F&SF, fled to Mexico for a while after abandoning the helm of this magazine. He clearly absorbed enough of the local color to vividly paint this tale. While ably told and a beautiful travelogue, the plot itself is rather slight, so I'm afraid three stars is my limit for this one.

Corona, by Samuel R. Delany

I've often complained that everybody else gets to review Chip Delany's work but me. Well, I got what's coming to me. This story involves a troublemaking hulk of a blue collar man named Buddy, who forms a rapport with "the prettiest little colored girl" named Lee, afflicted with uncontrollable telepathy. Said nine-year old has seen too much to want to live any longer. But her love for the popular music of Bryan Faust, particularly sharing it with Buddy, may give her a new lease on life.

If it weren't for the sentimentality, I'd say this is more Analog than F&SF. That said, despite the obvious attempts to be moving, I found myself curiously unmoved by this tale.

Three stars.

Music to My Ears, by Isaac Asimov

Speaking of music, Dr. A manages to take a potentially interesting topic–namely, the mathematical relationships between wave frequencies that underlie the fundamental scales of music–and make it not only dull as dishwater, but also virtually impenetrable.

And I have both a math and a music degree!

Two stars.

Alas, Poor Yorick! I Knew Him Well Enuff, by Joan Patricia Basch

Equity's a great gig. It's virtually impossible to get canned from a show when you're equity, even if you're dead! But what if you really need that not-dead skull who's a member of the guild to shut up so you can finish the damned play?

Basch has written a cute story, and it's likely to wring a grin or two from you, if nothing else.

Three stars.

Time, by L. Sprague de Camp

Poetry by a regular contributor of same, this time lamenting over the greats he'll never meet, and the fans he'll never know.

Three stars, I guess.

Cry Hope, Cry Fury!, by J. G. Ballard

We return to the crystalline seas of Vermillion Sands. A yachter by the name of Melville is stranded when his sand boat blows a tire. A wraith-like vision of a woman named Hope offers succor, but her obsession with an old flame (whom she may or may not have killed) belies the pleasant qualities of her namesake.

I tend to prefer Vermillion Sands stories to the more kaleidoscopic stuff Ballard has been turning in of late. There's more of a through-line. I also like the idea of photographic paints that depict ever-changing portraits of their subjects.

I don't think I'd give it four stars, but it's definitely interesting.

Praise be to Odin!

With no bad fiction and some solid hits in the first half of the mag, this issue of F&SF is definitely something to foray from home for (it's not as if the Vikings got home delivery of their sf mags.) That's something to toast to!

Here's looking forward to more of the same in the issues to come.

by Gahan Wilson

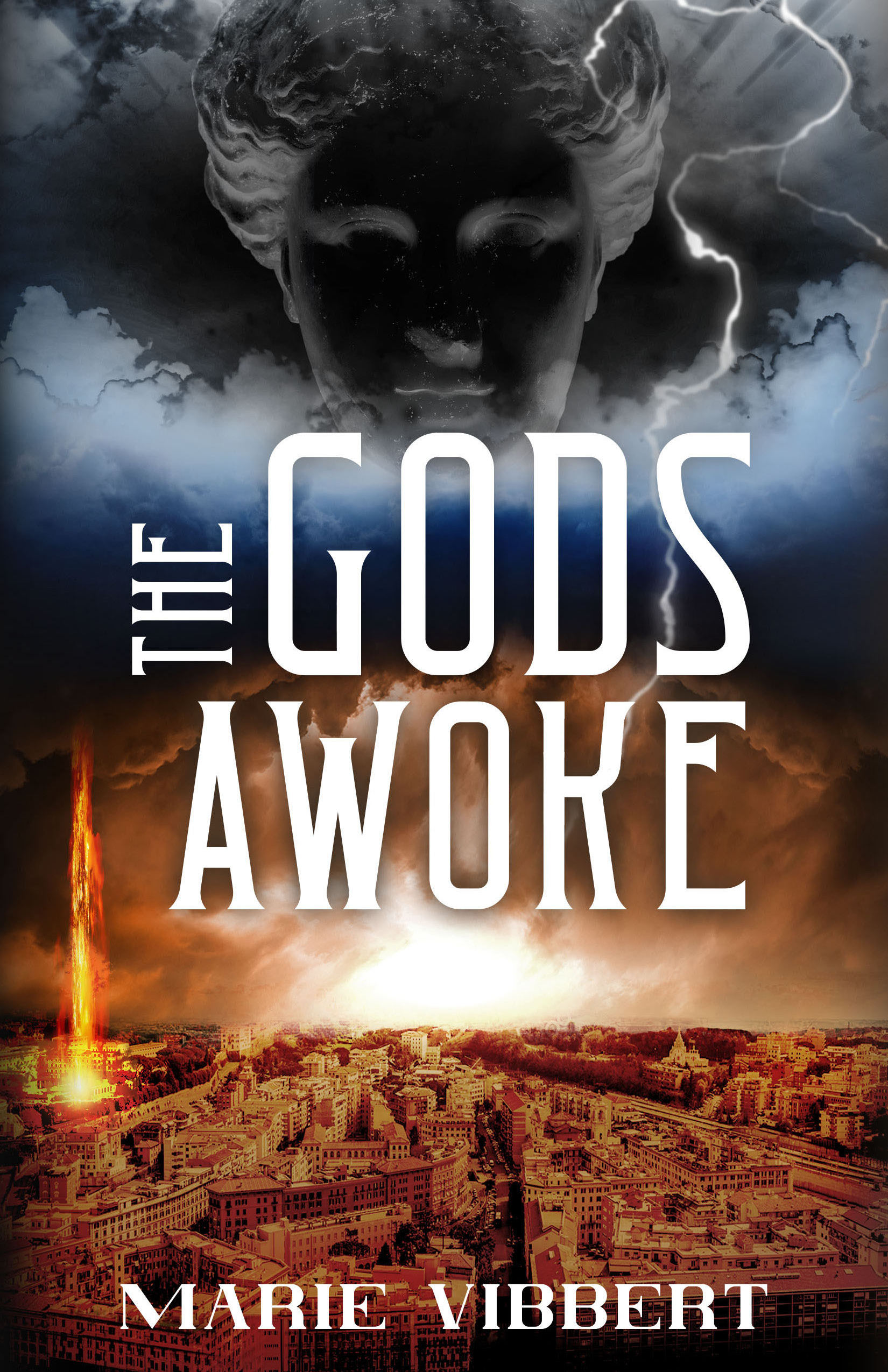

If you're here, you're obviously a big fan of classic fantasy and science fiction. As you know, I founded Journey Press to revive lost classics and to bring into bring new works that evoke that same timeless quality.

I think you'll very much enjoy our newest release. You've probably heard of Marie Vibbert, one of the biggest names in SFF magazines these days. Her book, The Gods Awoke, is what I've been calling "a new New Wave masterpiece":

Do check it out. You'll not only be getting a great book, but you'll be supporting the Journey!

![[September 18, 1967] Skål! (October 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/670918cover-672x372.jpg)

![[August 18, 1967] The Best and the Brightest? (September 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/670818cover-653x372.jpg)

![[July 20, 1967] An Analog of <i>Analog</i> (August 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/670720cover-659x372.jpg)

![[June 20, 1967] Yours sincerely, wasting away (July 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/670620cover-649x372.jpg)

![[May 20, 1967] Field trips (June 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/670520cover-449x372.jpg)

![[April 18, 1967] Bright Lights (May 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/670418cover-672x372.jpg)

![[March 20, 1967] Vistas near and far (April 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/670320cover-672x372.jpg)

![[March 12, 1967] Computerized Futures & Humanity (Out of the Unknown: Season Two)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Out-of-the-Unknown-2.jpg)

![[February 20, 1967] To Ashes (March <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/670220cover-661x372.jpg)

![[February 4, 1967] The Sweet (?) New Style (March 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/IF-Cover-1967-02-full-672x372.jpg)