by Fiona Moore

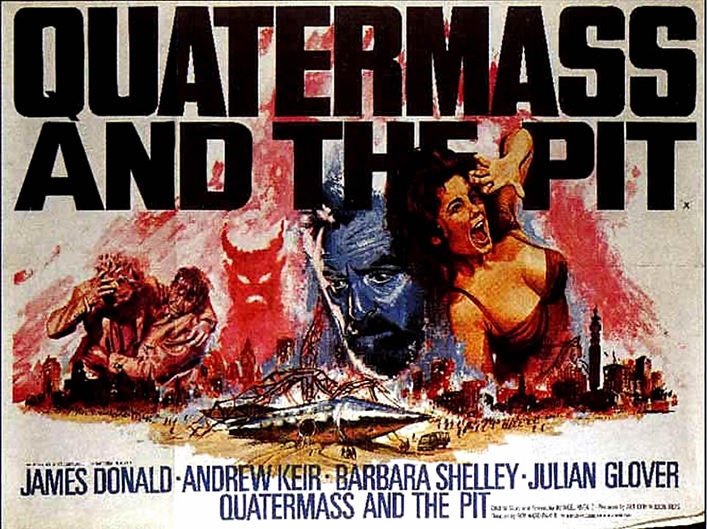

This month sees the release of a film I’ve been anticipating for a long time: Quatermass and the Pit, the final instalment in Hammer Film Productions’ adaptations of Nigel Kneale’s Quatermass trilogy. With a whole new cast of actors and a very different look and feel to Hammer’s earlier movies starring Brian Donlevy, The Quatermass Xperiment (1955) and Quatermass 2 (1957), this represents a concerted effort to bring Quatermass into the 1960s.

While reportedly this film was considered as another outing for Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee, Andrew Keir as Quatermass and Julian Glover as Breen provide great interpretations. Keir is the most likeable of the Quatermass actors, while still managing a bitter world-weariness in keeping with the character. Rising star Glover is a bold choice as Breen, being considerably younger than Anthony Bushell in the TV serial, but this casting shifts the interpretation from an old officer too set in his ways to acknowledge the impossible, to an immature, overpromoted man falling back on rigid denials to cover the fact that he is out of his depth. Barbara Shelley as Barbara Judd is more sexy than the usual Quatermass women, wearing outfits that one would think not very sensible for an archaeologist.

Likeable: Andrew Keir as Quatermass and Barbara Shelley as Miss Judd

Likeable: Andrew Keir as Quatermass and Barbara Shelley as Miss Judd

The basic narrative has had only a few updates. For instance, rather than a new building, the construction work which revives the ancient horrors is the digging of a new Underground extension, something which many Londoners are having to put up with right now. The story has been compressed from six half-hour episodes to a lean 97 minutes, meaning that the plot cracks along at a ripping pace without every feeling overpadded, and we lose most of Kneale’s excruciating working-class stereotype characters. On the more negative side, the film lacks the slow buildup of tension that the TV serial had. Crucially, the themes of the original are all present. Perhaps because Kneale is here adapting his own screenplay, we do not lose the sense of anger at military proliferation, colonialism, and humanity’s self-destructive tendencies.

Colonel Breen, representing humanity's negative side.

Colonel Breen, representing humanity's negative side.

One aspect which remains unchanged, however, leads to a rather specialised criticism I have of this movie, speaking as an anthropologist. While in 1959 the dominant theory about human evolution was, indeed, that large brains would precede upright walking, more recent discoveries by Louis and Mary Leakey in East Africa are starting to move the consensus more towards the idea that the opposite was true.

The colour film and production values give the film a much more lavish feel than the austere Donlevy movies, but are a mixed blessing. The alien spacecraft is a thing of beauty compared to the crude cylinder of the serial, but this makes the idea that it could be initially thought to be a German V-weapon less credible. The simple ground-shaking effect in the TV serial when Sladden (played here by Duncan Lamont) accesses his primitive side was somehow more terrifying than the wild poltergeist activity seen here. However, the climax of the film uses its production values to build on the sense of terror as humanity succumbs to the Wild Hunt: we have a chilling scene where a group of people surround a man and beat him to death telekinetically with stones and masonry. Rather than concluding with an explanatory speech by Quatermass, the film simply lingers on the image of Quatermass and Barbara sitting among the ruins, shattered by what they’ve experienced.

Hammer's take on the Martians.

Hammer's take on the Martians.

Quatermass and the Pit provides evidence both that the themes of the original Quatermass stories remain fresh and relevant almost a decade later, and that Hammer are still capable of producing a decent horror film without relying on gore and nudity to bring in the shocks. It’s a shame there’s unlikely to be a Quatermass 4.

Four out of five stars.

by Jason Sacks

Bonnie and Clyde

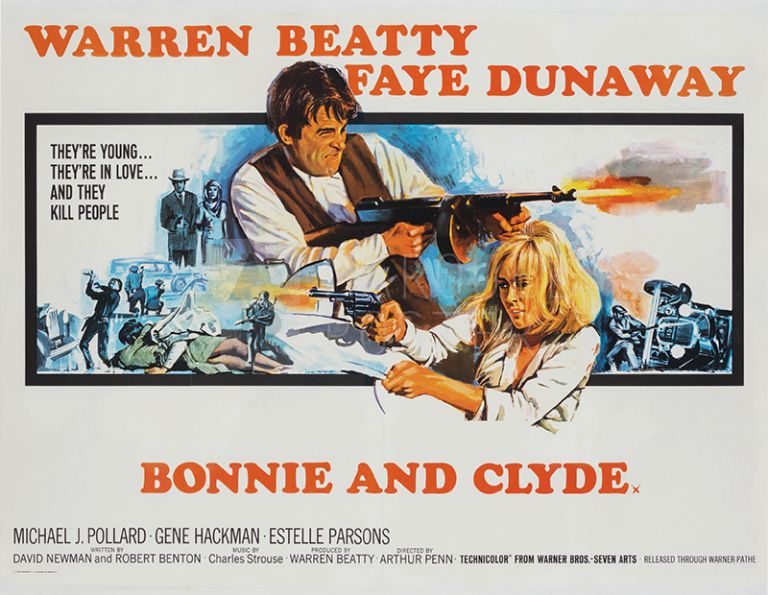

And while Fiona praises Quatermass and the Pit for its lack of gore, I have to praise Bonnie and Clyde for its copious use of gore.

You're probably aware of this newest film starring Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway. In the two months since its New York premiere, perhaps you've seen the numerous newspaper articles focusing on the highly violent nature of Bonnie and Clyde, or articles which have condemned the idea that the film makes heroes of its bankrobbing protagonists.

Or perhaps you've read the rhapsodic review of Bonnie and Clyde in the latest issue of The New Yorker by their new critic Pauline Kael and possibly dismissed it because of your annoyance with Kael's now legendary condemnation of The Sound of Music three years ago in McCall's.

I've had the most amazing experience since I saw Bonnie and Clyde last weekend after it premiered at the Northgate Cinema: I've been raving nonstop to my friends about this film.

Like Kael, I was thrilled to see a film which is so bold, so intense and somehow so contemporary feeling. Despite–or perhaps because of–its setting in during the Great Depression, this film feels like a deconstruction of the myths we have told ourselves about the past. Bonnie and Clyde makes villains out of the brave federal men who chase our heroic criminals. This isn't an episode of The FBI. This is an inversion of what it means to be a hero. And in that inversion I saw myself in the faces of people who lived and died 35 years ago.

Because the world in which Bonnie and Clyde live feels like a real world. It's dusty and ugly and people wear worn clothes. Some banks have collapsed and others are near collapse and peoples' lives are miserable. In that misery, ordinary people are desperate for someone, anyone, who is able to triumph against all odds, even if the fate of those heroes seems horribly preordained.

Like all of us, the characters in Bonnie and Clyde are deeply flawed. I was especially swept up in Clyde's foibles. We're all used to seeing Warren Beatty as the smooth handsome lover in movies like Promise Her Anything and Splendor in the Grass, but here Beatty plays a man who's just not interested in love, or maybe more truthfully Clyde is a man who gets his thrills from robbery and not from women. Faye Dunaway is thus not quite Beatty's girlfriend on screen as much as she is his accomplice, fascinatingly contrary to what we expect.

With its echoes of the French New Wave and its shattering of cliche and audience expectations, Bonnie and Clyde feels like a revolution–a harbinger of the types of films I hope to see as the new decade dawns.

4½ out of 5 stars

by Victoria Silverwolf

Beware of Greeks Bearing Gifts

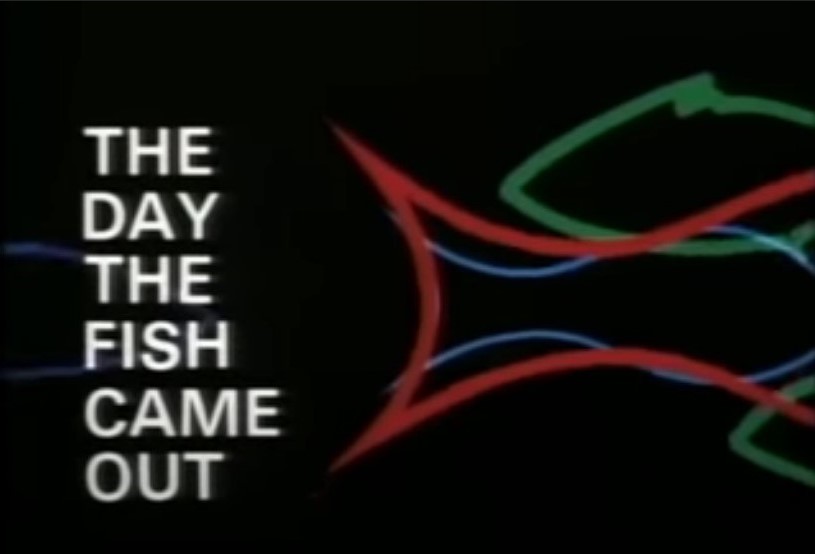

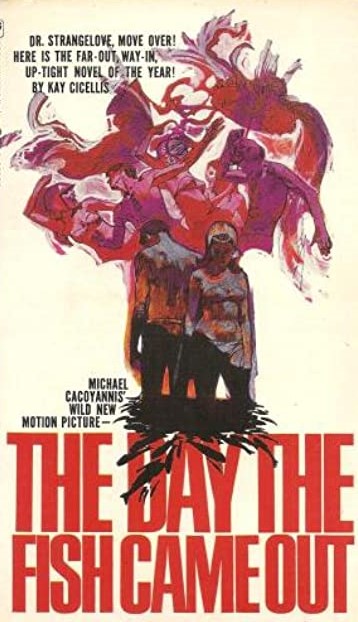

Filmmaker Michael Cacoyannis had an international hit with Zorba the Greek a few years ago, which was nominated for seven Academy Awards and won three. With that success behind him, I guess he figured he could do just about anything he wanted. He decided to do something different.

The film starts with an unseen narrator telling us about the tragic incident last year when a B-52 bomber collided with a tanker during mid-air refueling, killing most of the crew. Four nuclear bombs fell out of the doomed aircraft, three of them landing near the Spanish village of Palomares and one falling into the sea. Since this movie is a black comedy, this frightening story is accompanied by three flamenco dancers.

They also have the ability to sing with subtitles, giving away the plot.

In the future year 1972, a plane carrying a pilot, a navigator, two atomic bombs, and a mysterious metal box crashes near a tiny Greek island. The unfortunate pair of flyboys lose their clothing, and spend most of the film in their underpants.

Colin Blakely (left) and Tom Courtenay (right) offer a little beefcake.

A bunch of military types, pretending to be folks interested in building a hotel on the island, search for the bombs and box. They get the bombs back, but it seems a local fellow found the box and thinks it has a treasure inside. Unfortunately for him, it's sealed tight and can't be opened except by a laser or a special chemical. (Keep that latter possibility in mind.)

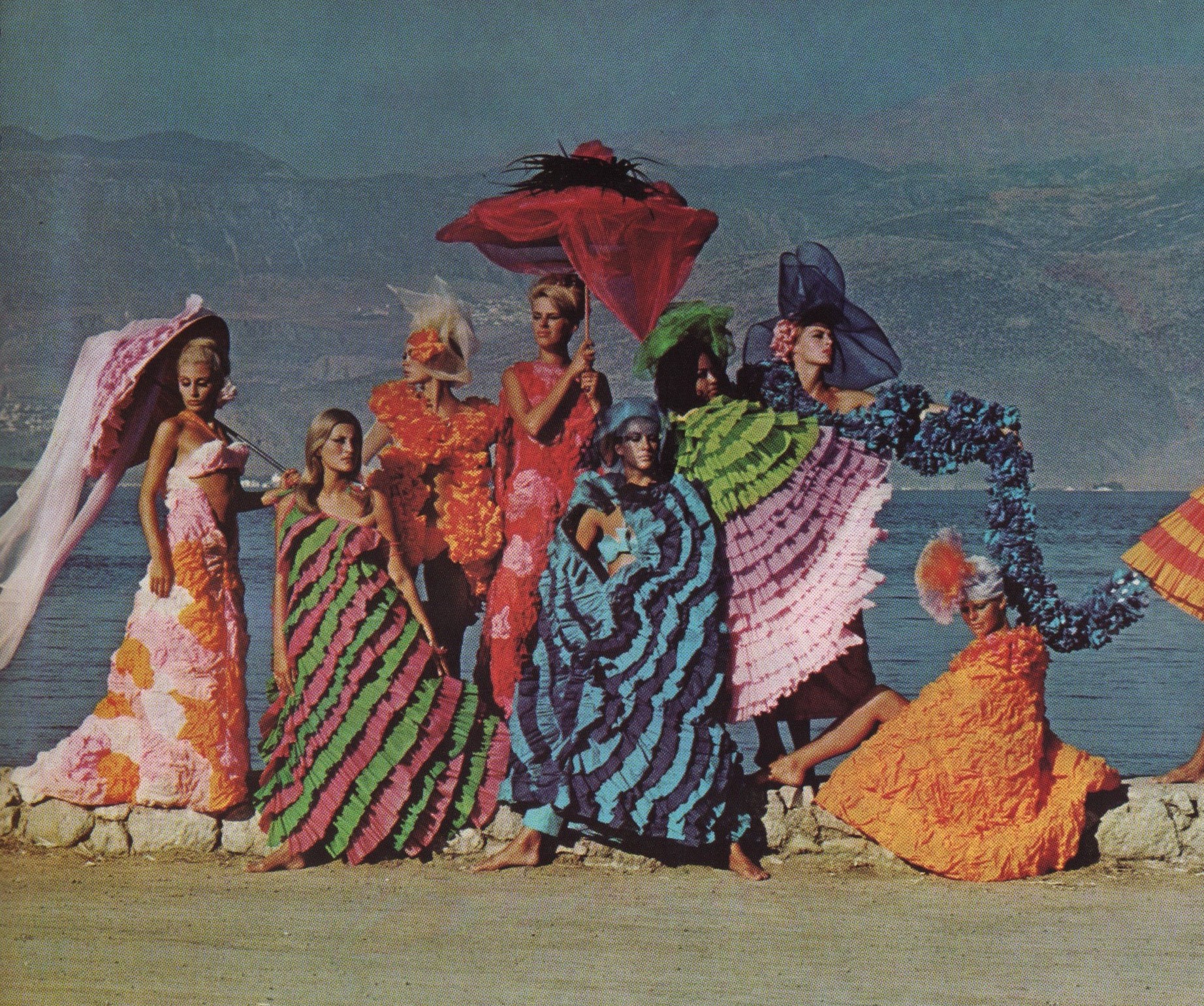

Meanwhile, a bunch of tourists, attracted by the rumor of an upcoming hotel, flock to the island. Like almost everybody else in this movie (not including the locals or the barely dressed airmen), they wear clothes that would be rejected by Carnaby Street as too extreme. They also dance a lot.

In fact, if you get a chance to watch the trailer for this movie, you'll think it's a beach movie.

After more than an hour of this stuff, the plot gets going with the arrival of Electra Brown, played by Candice Bergen, the beautiful daughter of ventriloquist Edgar Bergen. She's supposed to be an archeologist, but the way she behaves with one of the military guys makes me think she's more interested in human biology. Bergen made her film debut as a lesbian in the classy soap opera movie The Group, but here she is very heterosexual indeed.

Electra Brown in one of her more conservative outfits.

Electra has this weird device that uses a special chemical (sound familiar?) to cut through metal in order to make replicas of ancient objects. (No, that didn't make much sense to me either.) Long story short, the guy who found the box steals the gizmo, opens the box, and . . .

Well, without giving away too much, let's just say that the depressing ending finally explains the title. This movie badly wants to be Dr. Strangelove and it fails miserably. The comedy isn't funny, the satire falls flat, and there are long stretches where nothing much is happening.

Two stars, mostly for the wacky costumes.

Designed by the director, who also wrote and produced.

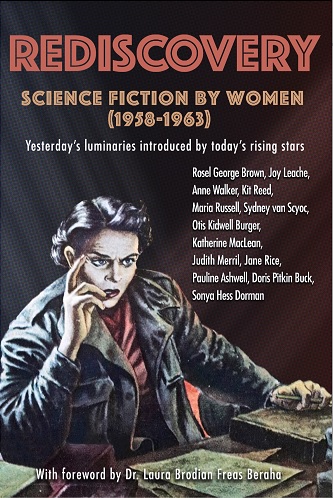

Stay away from this one unless you want to laugh at it. Read a book instead.

Maybe not this one.

by Cora Buhlert

Horror in the Real World

1967 is certainly turning out to be a year of disasters.

Belgium has barely recovered from the devastating fire at the À l'Innovation department store in May and now two express trains and a local passenger train collided near the village of Fexhe-le-Haut-Clocher in the French-speaking part of Belgium on October 5, leaving twelve people dead and 76 injured.

The photos of the wrecked trains bring back memories of another terrible railroad disaster that happened only three months ago in East Germany. A barrier at a railroad crossing near the village of Langenweddingen malfunctioned. As a result, a passenger train crashed into a tanker truck, setting the train on fire. 94 people died, 44 of them school children en route to a holiday camp. The Langenweddingen train crash is the worst railroad accident not just in East Germany, but in all of German history.

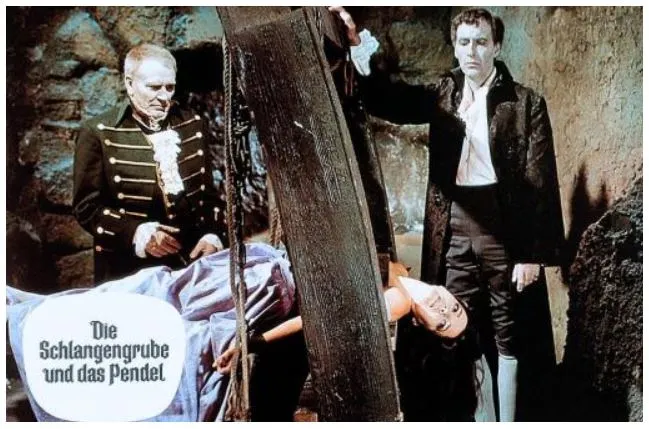

Horror on the Silver Screen: Die Schlangengrube und das Pendel (The Snake Pit and the Pendulum)

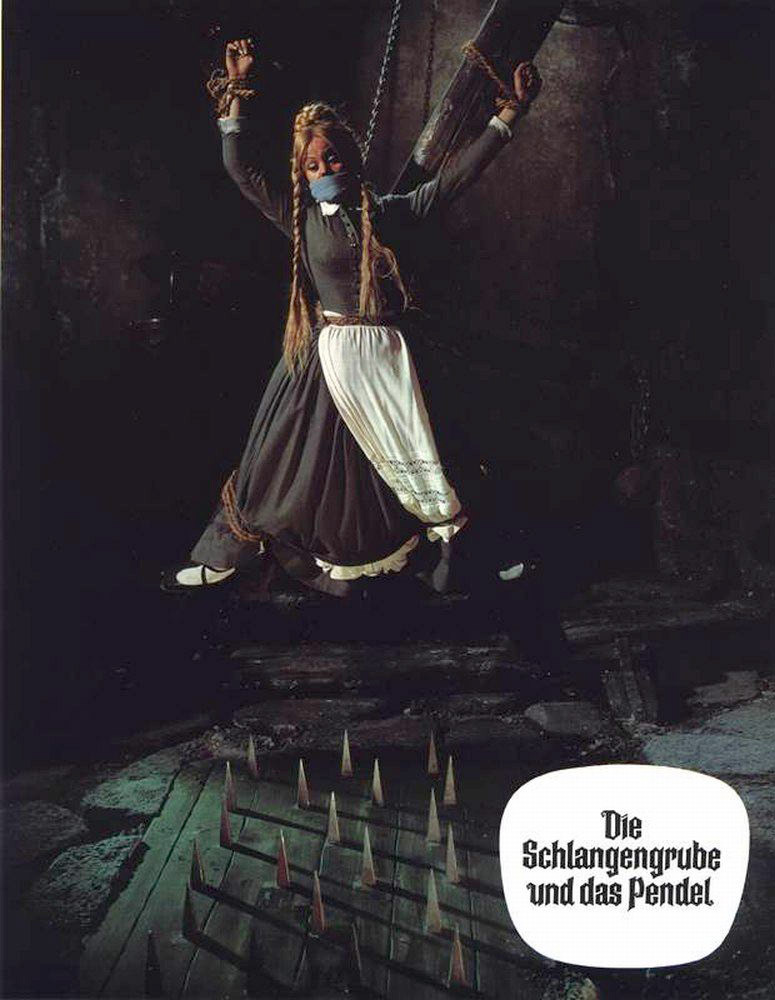

Compared to the many horrors of the real world, watching a spooky movie in the theatre feels almost cathartic. And so I decided to get away from the real world by watching the new West German horror movie Die Schlangengrube und das Pendel (The Snake Pit and the Pendulum) at my local cinema.

As the title indicates, the film is a (loose) adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe's "The Pit and the Pendulum". Of course, we already had a very good (loose) adaptation of that story by Roger Corman only six years ago. And indeed, The Snake Pit and the Pendulum intends to be West Germany's answer to Roger Corman's Edgar Allan Poe adaptations, the UK's Hammer horror films and the lurid horror films from Italy, all of which are popular, if not necessarily critical successes in West German cinemas. So how does The Snake Pit and the Pendulum hold up?

Pretty well, it turns out. The movie starts with a bang, as a bewigged judge and a scarlet-masked executioner visit Count Regula (Christopher Lee) in his cell. The judge informs Count Regula that he is sentenced to death for murdering twelve virgins in his quest for immortality. However, the immortality elixir requires the blood of thirteen virgins and the final virgin managed to escape the Count's clutches and alerted the authorities.

The death sentence is to be executed immediately and a most bloody sentence it is, too. First, a bronze mask lined with spikes is nailed onto Count Regula's face – reminiscent of Mario Bava's 1960 horror movie La Maschera del Demonio a.k.a. Black Sunday. Then Count Regula is led onto the market square of the fictional town of Sandertal – portrayed by the Bavarian town of Rothenburg ob der Tauber, which is famous for its medieval architecture – where his body is torn apart by four horses. Of course, we have seen similar scenes in Italian and French historical and horror movies many times, but by the rather tame standards of West German cinema, this is a remarkably bloody opening.

The movie continues in the same vein. For true to form, Count Regula has vowed bloody vengeance from beyond the grave, not only on the judge who sentenced him to death and that pesky virgin who escaped his clutches, but also on their descendants.

Vengeance from Beyond the Grave

The story now jumps forward by thirty years, from the early nineteenth century into the 1830s. A mail coach is traveling to Sandertal. The passengers are the lawyer Roger Mont Elise (Lex Barker), Baroness Lilian of Brabant (Karin Dor), her maid Babette (Christiane Rücker) and Fabian (Yugoslav actor Vladimir Medar), a highwayman masquerading as a priest. Roger and Lilian have both been summoned to Castle Andomai via mysterious letters. Roger, who is an orphan, is supposed to learn more about his parentage, while Lilian is supposed to receive the inheritance of her late mother. Both letters are signed by Count Regula, the very same Count Regula whose bloody execution we just witnessed.

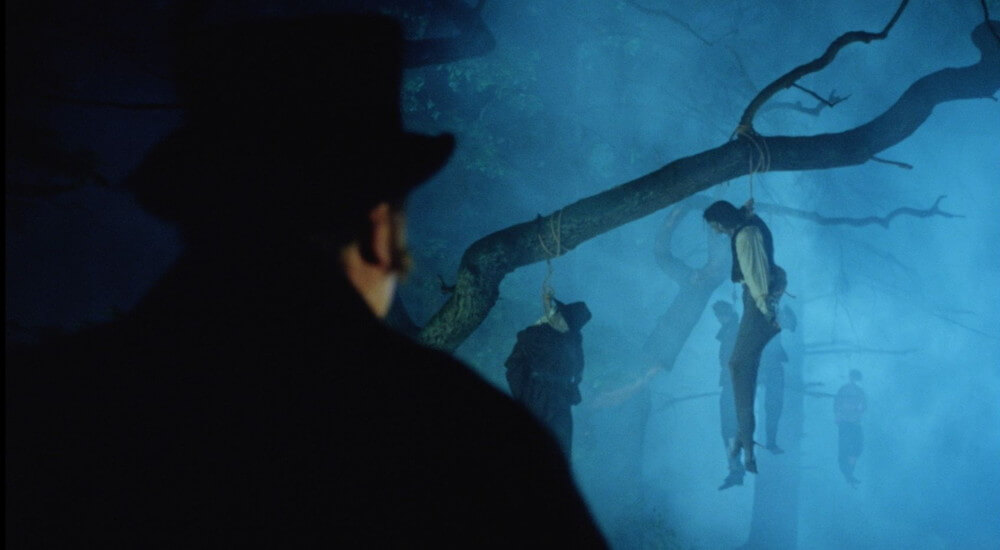

En route to the castle, the coach and its passengers must not only travel through a spooky forest where the bodies of hanged men are dangling from every tree, but are also assailed by bandits intent on kidnapping the two women. Roger and Fabian manage to fight off the bandits. But even more trouble awaits them at the castle, where the undead Count Regula and his equally undead servant Anatol (played by the delightfully creepy Carl Lange) are about to make good on the Count's dying threats.

For unbeknownst to them, Roger and Lilian are the descendants of the judge who sentenced Count Regula to death and the virgin who escaped the Count's clutches (and clearly did not remain a virgin). A gruesome fate awaits them at the castle, a fate that involves a pit full of snakes and a razor-sharp pendulum.

The Snake Pit and the Pendulum is not quite up to the high standards set by Roger Corman's Edgar Allan Poe adaptations on the one hand and the Hammer movies from the UK on the other. However, it is an enjoyably spooky film that will send a shudder or two down your spine.

Harald Reinl is a veteran of the Edgar Wallace, Dr. Mabuse and Winnetou movie series and probably the best director working in West Germany right now. His skills are on full display in this movie and he uses existing locations such as the medieval town of Rotenburg ob der Tauber or the Extern Stones in the Teutoburg Forest to great effect.

The cast is excellent. Christopher Lee has graced many a Hammer movie and now brings his horror skills to West German screens. Carl Lange has specialised in playing dubious characters and outright villains for a long time now and his performance as a hangman forced to execute his own son in Face of the Frog is unforgettable. I'm always stunned that Lex Barker never got to be the A-list star in Hollywood that he is in Europe, but their loss was our gain. That said, at 48 Barker may be getting a little too hold for hero roles. Finally, I'm very happy to see the always reliable Karin Dor back in a West German production and with her natural brunette hair after the James Bond movie You Only Live Twice wasted her talents on a cliched femme fatale role and foisted a terrible red wig on her, too.

Almost fifty years ago, the horror film genre was born in Germany. But like so many other things, horror film making in Germany died with the Weimar Republic. Let's hope that The Snake Pit and the Pendulum heralds a revival of a film genre that was pioneered here.

Four stars

![[October 18, 1967] We Are The Martians: Quatermass and the Pit, Bonnie and Clyde, The Day the Fish Came Out and The Snake Pit and the Pendulum](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/671018posters-672x372.jpg)

![[May 14, 1966] Seeing Double (<i>The She Beast</i> and <i>The Embalmer</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/unnamed-1-512x372.jpg)

![[March 4, 1966] Sanguinary Cinematic Surgery (<i>Blood Bath</i> and <i>Queen of Blood</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/660304movie-600x372.jpg)

![[April 8, 1965] Twisted but Classy (Mario Bava's "Blood and Black Lace")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/BBLposter-672x372.jpg)

![[September 10, 1964] Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered (September 1964 Television Debuts)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/640910munsters-500x372.jpg)

![[June 24, 1964] Death Has No Master (Roger Corman's <i>The Masque of the Red Death</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/masqueposter-672x372.jpg)

![[June 10, 1964] What washed up (<i>Horror at Party Beach</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/640610horror-459x372.jpg)

![[April 24, 1964] Some Justice to Mete Out (<i>The Twilight Zone</i>, Season 5, Episodes 25-28)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/640424a-672x372.jpg)

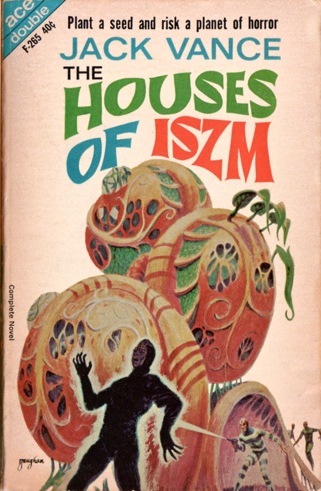

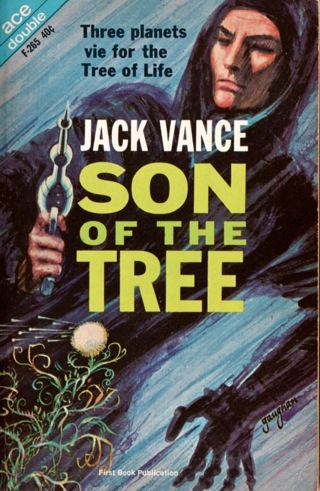

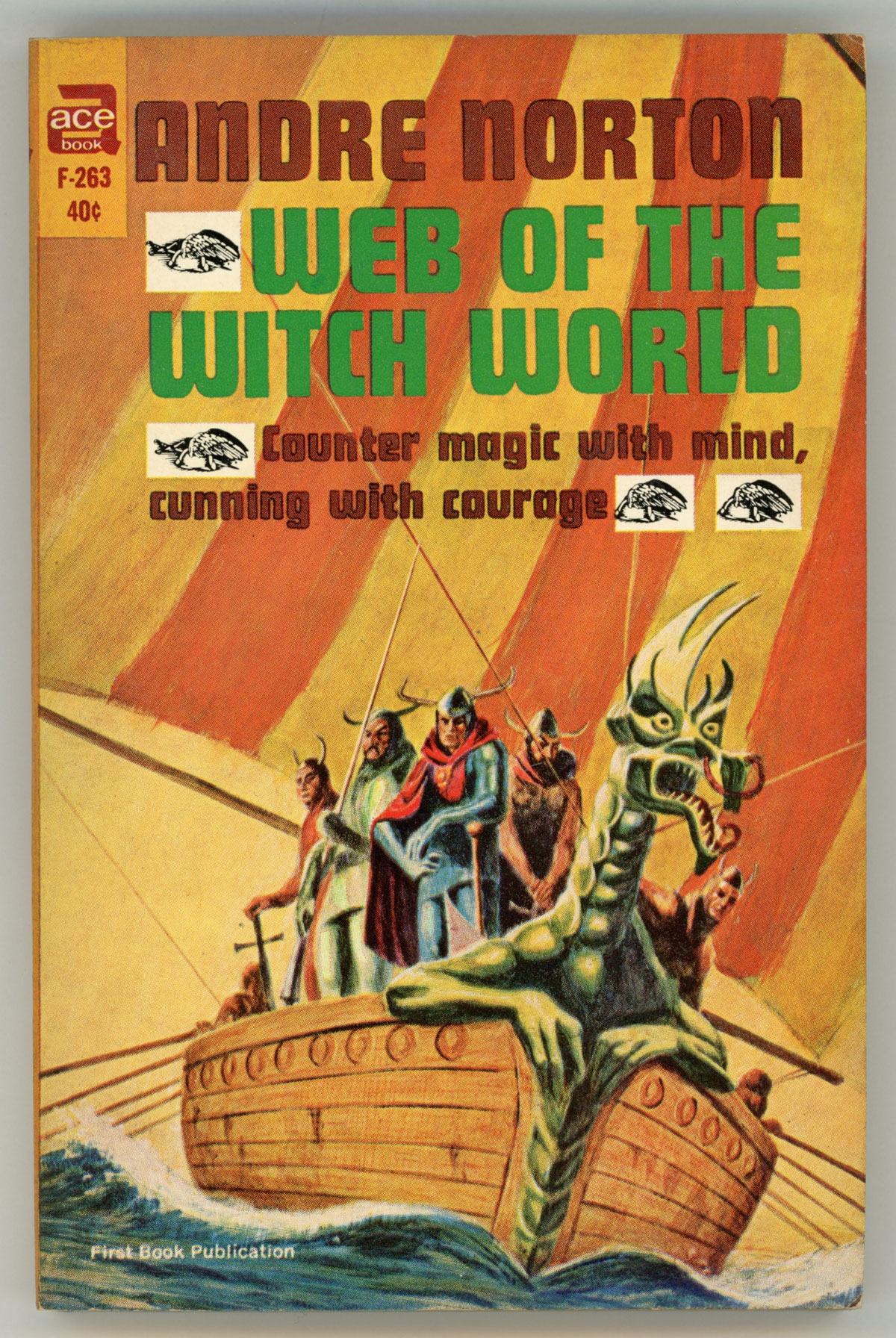

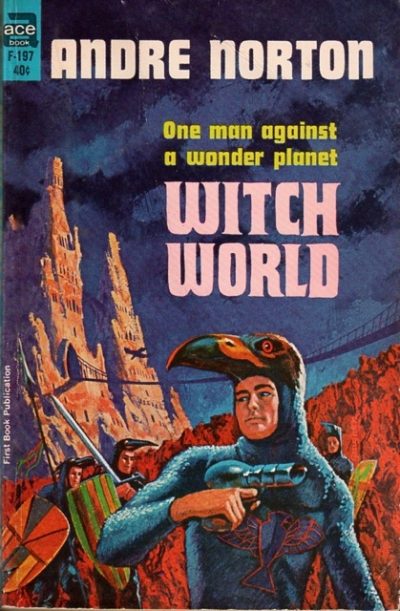

![[April 16, 1964] Of Houses and World Building (Jack Vance's The Houses of Iszm/ Son of the Tree and Andre Norton's Web of the Witch World)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/640416double-640x372.jpg)

![[March 19, 1964] When Vampires Rule the World (Ubaldo Ragona and Sidney Salkow's <i>The Last Man on Earth</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/640319lastmanposter-672x372.jpg)