by Victoria Silverwolf

After the Ball is Over

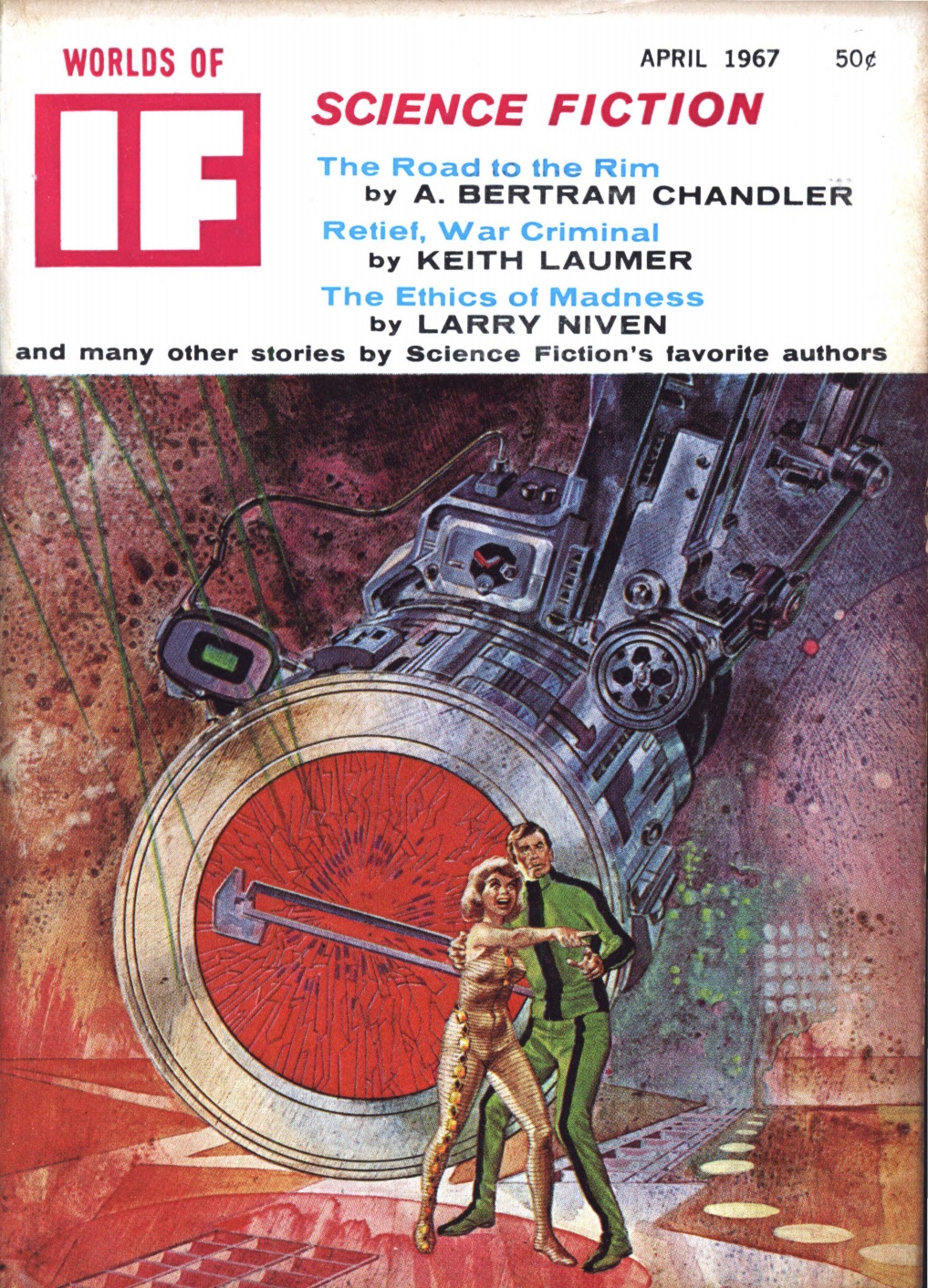

According to my sources in the publishing world, the latest issue of Worlds of Tomorrow is the last one that will be published. I can't say I'm completely surprised, given Frederik Pohl's juggling act of editing three magazines at once. Worlds of Tomorrow is the youngest of the literary siblings, and seems to have received the least attention. (The fact that it went from bimonthly to quarterly is a strong clue.)

While the band plays Goodnight, Ladies and my corsage begins to wilt, let's take one last waltz around the ballroom.

Save the Last Dance For Me

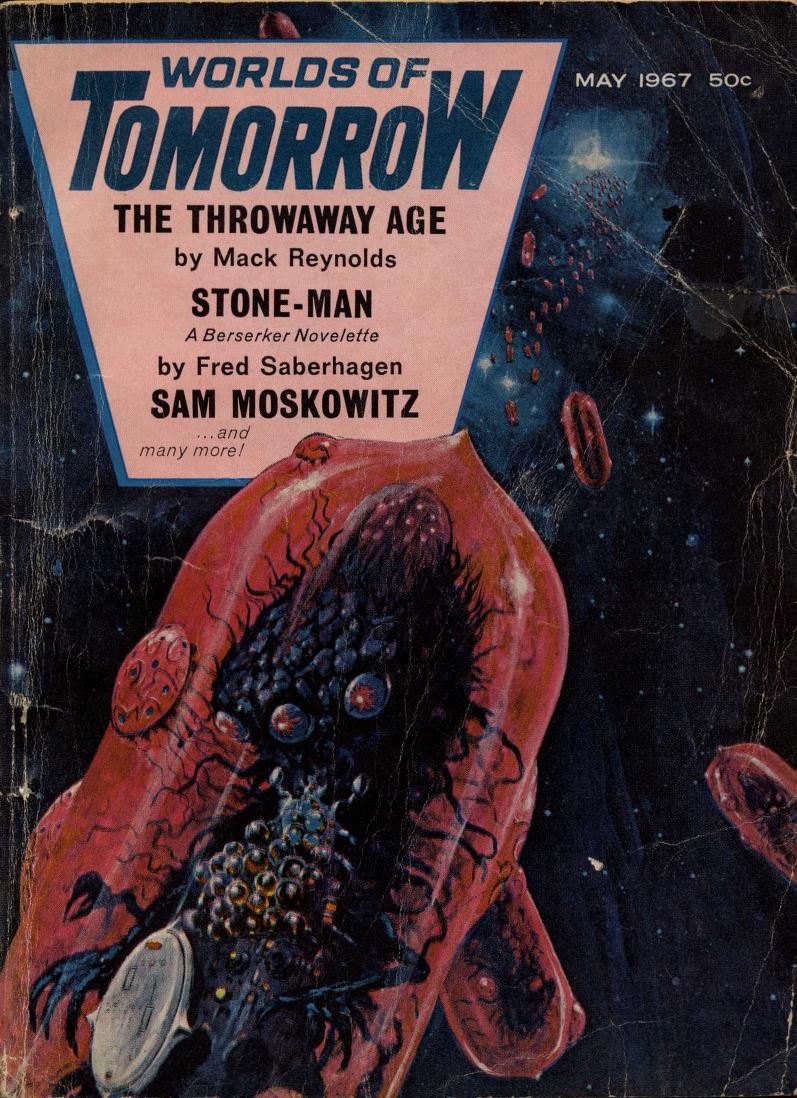

Cover art by Douglas Chaffee.

Stone Man, by Fred Saberhagan

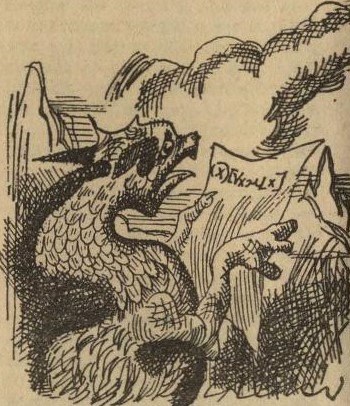

Illustrations by Hector Castellon.

Here's the latest story in the author's Berserker series, featuring ancient machines bent on destroying all organic life. This yarn features a peculiar kind of time travel, which requires some explanation.

Humans settled a planet where some kind of weird space/time warp sent them into the remote past. It also wiped out their memories, so they pretty much started from scratch as cave dwellers. Many generations later, society evolved into one with advanced technology. Then the Berserkers showed up.

The planet's surface became a war-scarred wasteland, and the remaining population went underground. Making use of the same space/time warp, the Berserkers try to completely eliminate the human population by sending war machines to the past.

Our hero, a young cave dweller, and a Berserker device.

The main character sends his consciousness into an armored suit that goes back in time, in order to intercept the machines. (I will refrain from making a head 'em off at the past joke.)

A closer look at the enemy. The cave folk call it a stone-lion, and call their rescuer a stone-man.

It won't surprise you that our hero saves the day, after a very tough battle. (Let's ignore the fact that his body remains in the future while his mind inhabits the armor, so his life isn't really in danger. Anyway, if the Berserkers had won, he and the rest of the people on the planet would never have existed. Time travel is confusing, isn't it?)

He deserves to celebrate his victory.

What most impresses me about the Berserker series is that the author avoids repeating himself. (I wish I could say the same for the Gree and Esks series, or even Retief.) This is a pretty good story, but I have some quibbles.

There's a character I haven't mentioned yet, a young woman who suffers amnesia during one of the Berserker's attacks on the underground dwellers. (In the future, not the past. Are you still with me?) Her only role in the story seems to be to listen to the hero's expository dialogue. The premise is a complicated one, so I understand why the author needs to explain things to the reader via this character. However, like the plot itself, this strikes me as contrived.

I'd say a solid three stars for this one.

The Negro in Science Fiction, by Sam Moskowitz

Another article from the walking encyclopedia of fantastic fiction. As usual, this essay wanders all over the place, from dime novels of the Nineteenth Century to the present day. A lot of time is spent on obscure old stuff. The author seems to have his heart in the right place, decrying science fiction's failure to deal with modern issues of civil rights, but he also makes excuses for grotesque stereotypes from the last century. (As long as characters are on the side of the good guys, it doesn't seem to matter how they look, talk, or act.)

Two stars for a dull look at a very important topic.

Squared Out with Poplars, by Douglas R. Mason

Illustrations by Dan Adkins.

On behalf of the museum where he works, the protagonist journeys to the remote home of an eccentric fellow who intends to sell his collection of valuable artifacts. Along the way he runs into the elderly guy's beautiful granddaughter, who is headed the same way. After a difficult struggle to even reach the place, they discover the old man's bizarre secret project.

Dragging away one of the fellow's minions.

This is an odd story. I don't want to give away too much, but the premise involves truly weird technology that includes computers, human consciousness, and the trees that give us the title. In essence, it's a Mad Scientist yarn, with maybe a touch of James Bond. It's also written in an eccentric, affected style. The author doesn't seem to intend it as a comedy, but there are snide remarks from the hero all the way through it. At least it didn't bore me.

A wobbling three stars for originality, if nothing else.

The Uncommunicative Venusians, by David H. Harris

Illustrations by Jack Gaughan.

Forget the title. This is an article on symbolic logic, using syllogisms with science fiction elements that could have easily been replaced with something more mundane. The author seems to know what he's talking about, but his attempt to sugarcoat a math lecture with aliens and UFOs doesn't liven things up much.

The best thing about this piece is the above illustration, which adds a futuristic touch to Sir John Tenniel's original portrait of the Caterpillar from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.

Two logically derived stars for this homework assignment.

Base Ten, by David A. Kyle

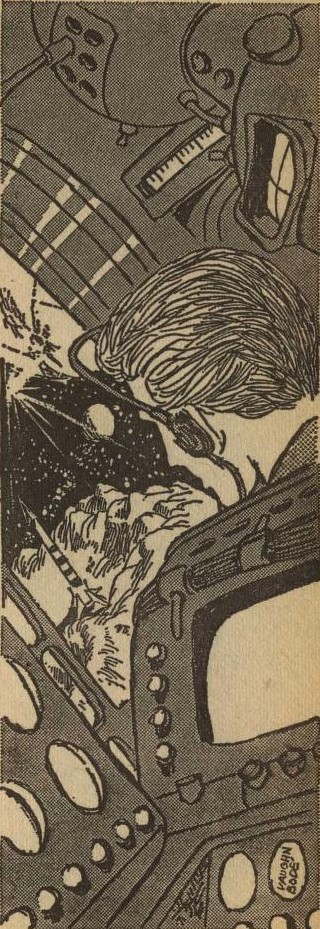

Illustrations by Vaughn Bode.

A man in a spaceship comes across a derelict rocket on an asteroid. The relic is way out of date, so he knows it's been there quite a while. Surprisingly, there's still someone alive inside the thing, in very bad shape.

Studying the castaway's notes.

The survivor tells him an incredible story about running into small aliens on the asteroid. They were friendly enough, but didn't want Earthlings to know about their existence.

Examining the old rocket's complex operating system, which is an important part of the plot.

The older fellow, who is half-insane from many years of isolation, offers vague hints of why he wasn't able to leave the asteroid, although the rocket had plenty of fuel. Meanwhile, the younger man tries to figure things out from the survivor's records.

Including drawings of the so-called Redheads, who resemble potato/mushroom combinations with limbs.

Try as he might, the young fellow isn't able to keep the older man from suffering a tragic fate.

Giving in to despair.

At the end, he figures out why the survivor was unable to return to Earth.

Saying goodbye.

The beginning intrigued me, but the aliens are silly and the solution to the mystery is disappointing and implausible. I'm not sure why this minor puzzle story needed so many drawings, but I'm sure the artist was glad for the work.

Two heavily illustrated stars.

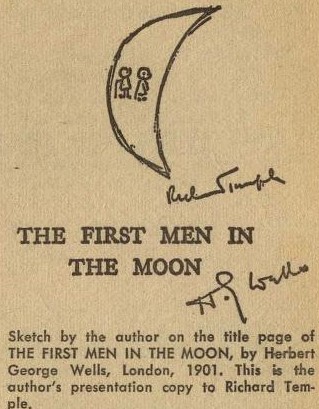

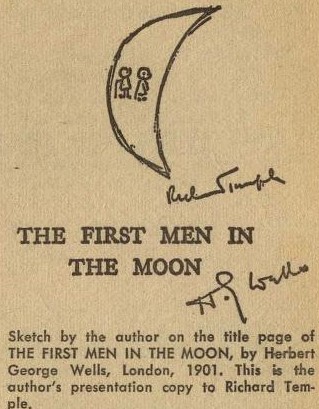

Syracuse University's Science-Fiction Collections, by Richard Wilson

There's not much to say about this article. It talks about the archive of books, magazines, manuscripts, and such mentioned in the title. It's good to know that scholars will have access to all this stuff, anyway.

A nifty example of the university's collection.

Two carefully indexed stars.

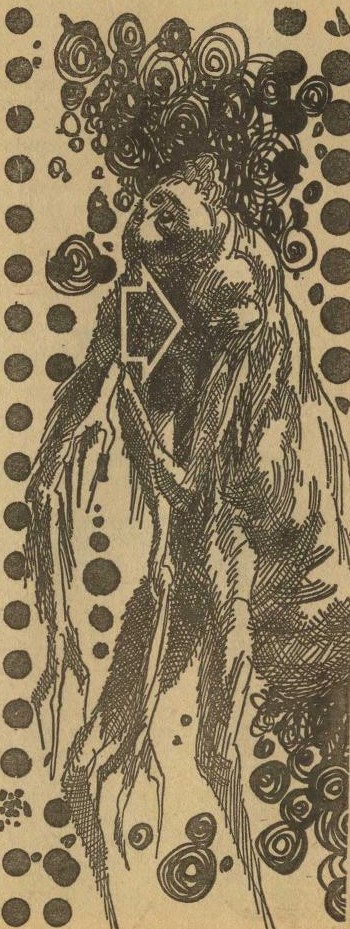

Whose Brother Is My Sister?, by Simon Tully

Illustrations by Jack Gaughan.

Some time after aliens arrived on Earth, the two species intermingled to such a degree that there are more extraterrestrials on the planet than humans. (The situation is said to be similar on the alien home world, but that's not really part of the plot.) The aliens are able to travel across the cosmos because they figured out that the current universe is absorbed by a new universe every instant.

(Don't worry if that doesn't make much sense to you. I felt the same way. And don't get me started on the debate as to whether the new universe is a lot smaller or a lot bigger than the old universe.)

The aliens have a chance to enclose the current universe inside some kind of so-called box, which will stop the passage of time. For some reason, they assume this will lead to an eternal paradise for everyone. Hardly anybody, human or alien, disagrees with this nutty scheme, except for a few religious folks.

Can you guess that things don't go as planned?

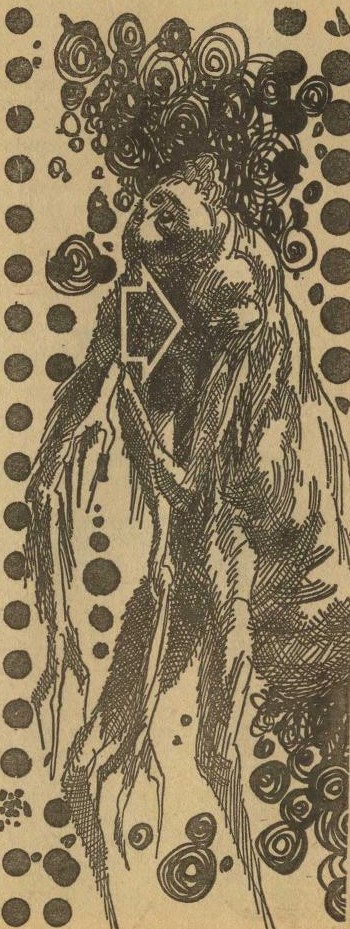

The arrow is a clue.

The best things in this story are the aliens. The author shows a great deal of creativity and imagination in describing their physical appearance, culture, and biology. (They have three sexes!) I would gladly read about their lives instead of all the nonsense about universes instantaneously eating up other universes, putting a box around the universe, and freezing time.

An ambiguous three stars.

The Throwaway Age, by Mack Reynolds

Illustrations by Gray Morrow. Notice the fine choice of reading material.

At some time in the near future, both the capitalist West and the communist East have expanded their territories, but the Cold War has cooled down considerably. So much so, in fact, that the best undercover agent for the West is reassigned from covert action behind the Iron Curtain to domestic snooping.

Sing along with me! There's a man who lives a life of danger . . .

The superspy, a fervent anti-communist (understandable, given his background) is bitter about what seems like a severe demotion. However, he accepts what he thinks will be a trivial assignment to infiltrate a very small and loose group of folks who want to change the economic system. They don't even have an organization, really, or a name for their movement. Harmless enough, but he runs into trouble along the way.

. . .With every move he makes/another chance he takes . . .

The members of this loose-knit bunch range from a gung-ho activist to a statistician to a ex-CIA agent. The one thing they have in common is the belief that both the West and the East are wasting resources and preventing humanity from reaching a higher level of civilization.

Did I mention that one of them is a pretty young woman, the daughter of the group's de facto leader, with whom the spy interacts in true Bondian fashion?

. . .Swingin' on the Riviera one day . . .

This is a manifesto disguised as a spy story, which in turn is disguised as science fiction. The futuristic elements, such as personal hovercars, are irrelevant. The espionage plot is just an excuse for lectures about socioeconomic issues.

I wish I liked this story more than I do. Reynolds is one of the few authors willing to deal with such topics, and he does so in a sophisticated way. He also has the rare virtue, for an American writer, of being cosmopolitan. His foreign settings and characters are authentic and vividly portrayed. Too bad this isn't really a work of fiction.

Two disappointed stars.

We'll Meet Again

I may have to take back what I said at the start of this article. Editor Pohl plans to continue the magazine for a while, or so he says.

That contradicts everything I've heard about the impending demise of the publication. We'll see which one of us is the better prophet.

Looking back on the magazine's history, it's a very mixed bag. There were a few excellent works of fiction, along with a lot of lesser pieces. Among the very best were All We Marsmen by Philip K. Dick (now available in book form as Martian Time-Slip; To See the Invisible Man by Robert Silverberg; The Totally Rich by John Brunner; The Worlds That Were by Keith Roberts; and The Star-Pit by Samuel R. Delany. I may have forgotten other outstanding stories. The frequent nonfiction articles were not as noteworthy.

Whether Worlds of Tomorrow shows up again in a few months or not, I am grateful that the Noble Editor gave me the opportunity to trip the light fantastic with it.

Let's tango!

Joan Baez is arrested in Oakland.

Joan Baez is arrested in Oakland. Fr. Berrigan pouring blood into a file drawer.

Fr. Berrigan pouring blood into a file drawer. Futuristic combat in The City of Yesterday. Art by Chaffee

Futuristic combat in The City of Yesterday. Art by Chaffee

![[November 4, 1967] Conflicts (December 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/IF-1967-12-Cover-672x372.jpg)

![[October 2, 1967] Switching Sides (November 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/IF-1967-11-Cover-672x372.jpg)

The logo for the traffic changeover.

The logo for the traffic changeover. This photo was staged several months ago as part of the education campaign. The real thing was much less chaotic.

This photo was staged several months ago as part of the education campaign. The real thing was much less chaotic. A newcomer gets the cover. Does he deserve it? Art by Vaughn Bodé

A newcomer gets the cover. Does he deserve it? Art by Vaughn Bodé![[September 2, 1967] Of Genies and Bottles (October 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/IF-Cover-1967-10-672x372.jpg)

William C. Foster, the chief American representative to the Eighteen Nation Committee on Disarmament.

William C. Foster, the chief American representative to the Eighteen Nation Committee on Disarmament. The art is intriguing, but none of this happens in Hal Clement’s new novel. Art by Castellon

The art is intriguing, but none of this happens in Hal Clement’s new novel. Art by Castellon![[June 2, 1967] Uneasy Alliances (July 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/IF-Cover-1967-07-672x372.jpg)

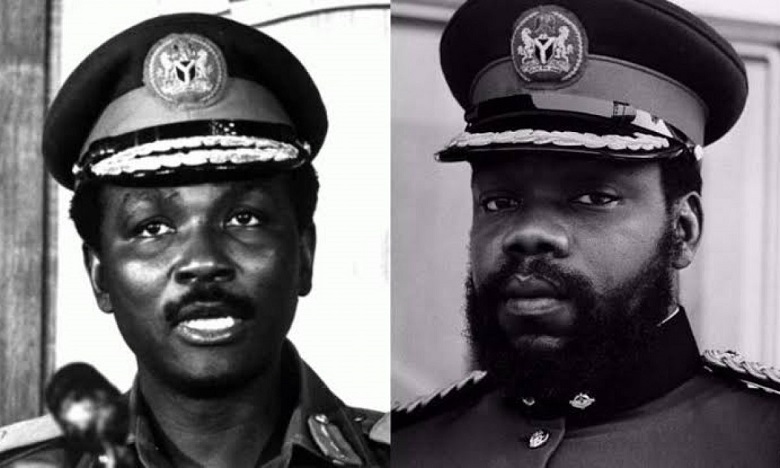

l.: Colonel Yakubu Gowon of Nigeria. r.: Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu of Biafra.

l.: Colonel Yakubu Gowon of Nigeria. r.: Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu of Biafra.  Joe Miller is the most fearsome warrior these vikings have ever seen. Art by Gaughan

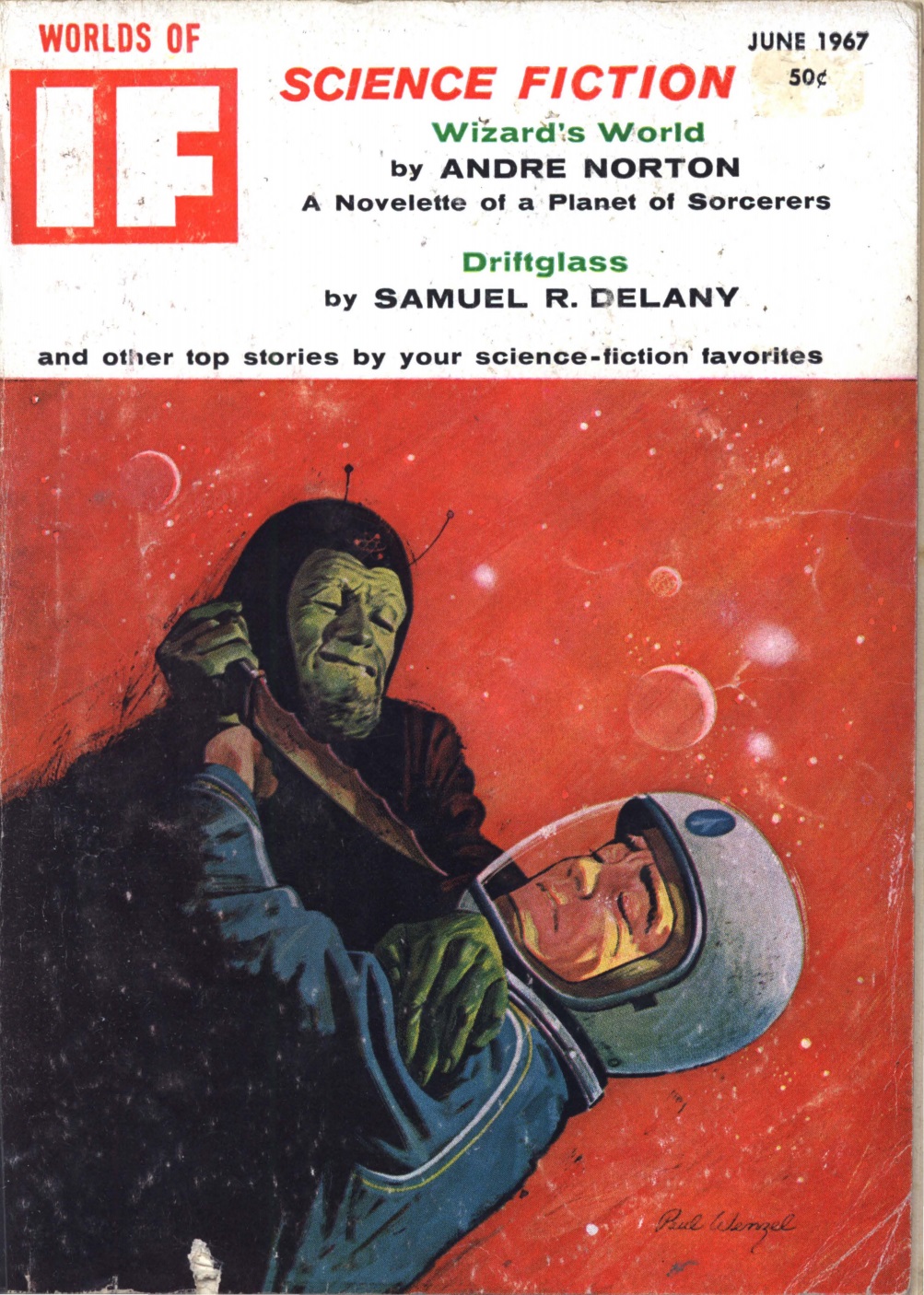

Joe Miller is the most fearsome warrior these vikings have ever seen. Art by Gaughan![[May 2, 1967] The Call of Duty (June 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/IF-Cover-1967-06-672x372.jpg)

Muhammad Ali is escorted from the induction center in Houston, Texas.

Muhammad Ali is escorted from the induction center in Houston, Texas.  Uncle Martin and Tim (from My Favorite Martian) seem to have had a falling out. Actually, this is supposedly from Spaceman!

Uncle Martin and Tim (from My Favorite Martian) seem to have had a falling out. Actually, this is supposedly from Spaceman!![[April 8, 1967] Swan Songs (May 1967 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v04n04_1967-05_0000-2-672x372.jpg)

![[April 4, 1967] Transitions (May 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/IF-Cover-1967-05-672x372.jpg)

What are these robots up to? Art by Gaughan

What are these robots up to? Art by Gaughan![[March 4, 1967] Mediocrities (April 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/IF-Cover-1967-03-672x372.jpg)

![[February 4, 1967] The Sweet (?) New Style (March 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/IF-Cover-1967-02-full-672x372.jpg)

![[January 16, 1967] Off to a Good Start (February 1967 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v04n03_1967-02_0000-2-672x372.jpg)