By Mx Kris Vyas-Myall

Over here in Britain the summer season is truly with us. Doctor Who is taking its annual break, the temperature reached 88 recently, and the free concerts in Hyde Park are in progress, having so far featured such performers as Donovan, Richie Havens, The Rolling Stones and the new merger of Traffic and Cream (tentatively called Blind Faith).

Clapton, Baker, Grech and Winwood jam together in the park

In this kind of heat, I personally find there is nothing better than setting up a blanket in the garden and reading a short story collection. Thankfully, I recently got hold of two I was interested in.

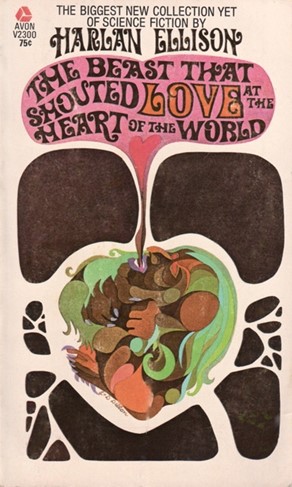

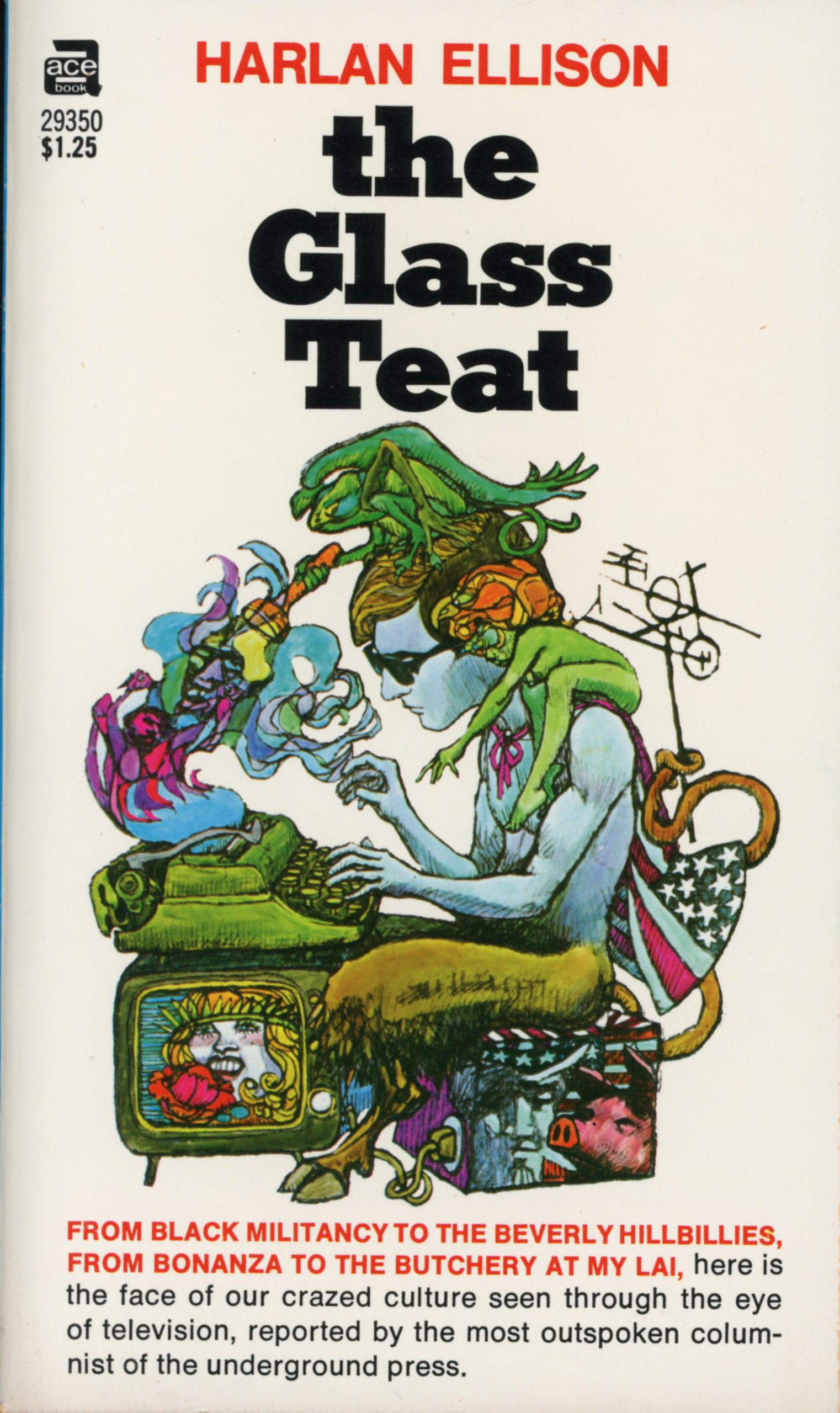

I will start with the angriest young man of Science Fiction, Harlan Ellison:

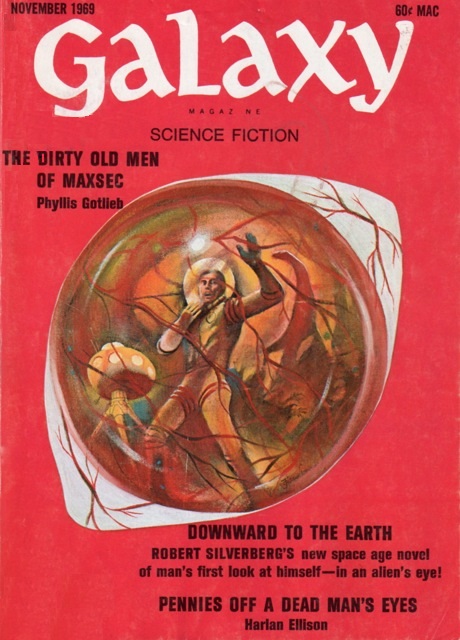

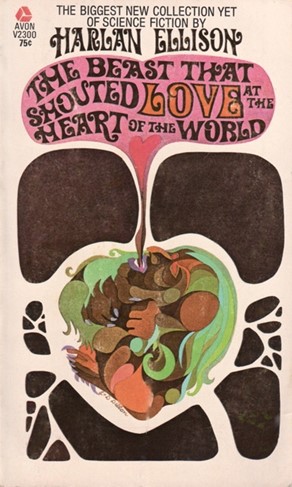

The Beast That Shouted Love at the Heart of the World by Harlan Ellison

His introduction seems to be primarily aimed at critics that try to apply easy labels to his fiction like avant-garde, new wave, or sci-fi (this last apparently coming in vogue with mainstream critics over the more common SF from fan circles). Whilst I get his point that it can be reductive to simply group J. G. Ballard and Samuel R. Delany together as if the were two pulp hack writers pumping out the same work, I also think there is value to talking about how this new type of fiction differs from what came before.

I also think Ellison is just being his usual grouchy self.

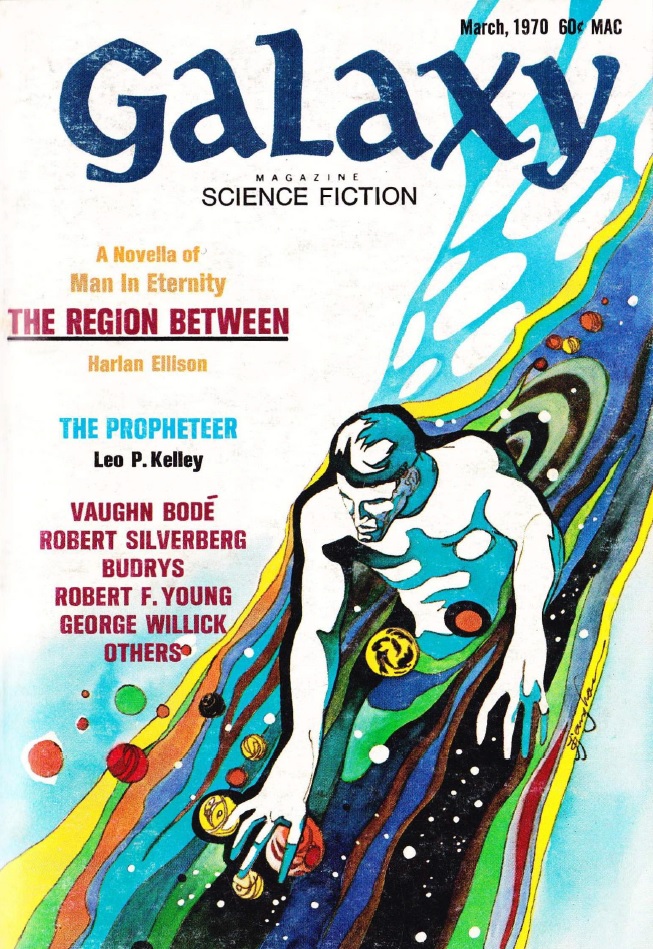

The Beast That Shouted Love at the Heart of the World

The titular story in this collection was previously published in Galaxy last year. However, Ellison was so unhappy with his changes, he has vowed to never write for Pohl again. Then again, given that Pohl is not actually an editor anymore that seems like an easy promise to keep.

I have read the piece three times and I am not sure what to make of it. It seems to posit madness coming from somewhere outside of us, Crosswhen (which seems to be either alternate timelines or another dimension) but yet also at the beginning of the universe.

In addition there are only 2 very minor edits made between this version and the magazine. One is changing one word to give clarity of linear time, the other is a paragraph describing the creature being placed in amber. These clearly were meaningful enough to cause a major fallout between Pohl and Ellison but the reason for this is a mystery to me.

Two stars, I guess?

Along the Scenic Route

To the best of my knowledge this is original to this collection, although it may have appeared in one of the “adult” magazines he sometimes writes for.

In this future, the freeways have become a battleground, where drivers duel in customised cars. When an ordinary driver is annoyed by the top ranked duellist in the world, he becomes involved in the conflict.

As a non-driver, I rarely relate to stories involving cars and this is no exception. It seems to be saying something about the stress and competition of driving the L.A. freeways, but I am honestly unsure what.

Two Stars

Phoenix

From the March edition of If. Red travels across the desert, determined to complete the expedition with one member already dead.

A disappointing effort from Ellison that started out in an interesting literary style but became cliché driven and dull by the end.

David gave this a low three stars, but I will drop it down to two.

Asleep: With Still Hands

Once again, a piece emerging out of the pages of If (Last July). For six centuries the Sleeper has sat at the bottom of the Sargasso sea, keeping the peace of the world. Any thoughts of war can be stopped by his telepathy. However, a specially trained group are determined to free the world from this Sleeper.

This feels to me like a drawn out version of Harry Lime’s speech in The Third Man:

In Italy, for thirty years under the Borgias, they had warfare, terror, murder and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance. In Switzerland, they had brotherly love, they had five hundred years of democracy and peace – and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock

Atmospheric but not as deep as Ellison clearly thinks it is.

In this case I will stick to David’s 3 stars, albeit a low one.

Santa Claus vs. S. P. I. D. E. R.

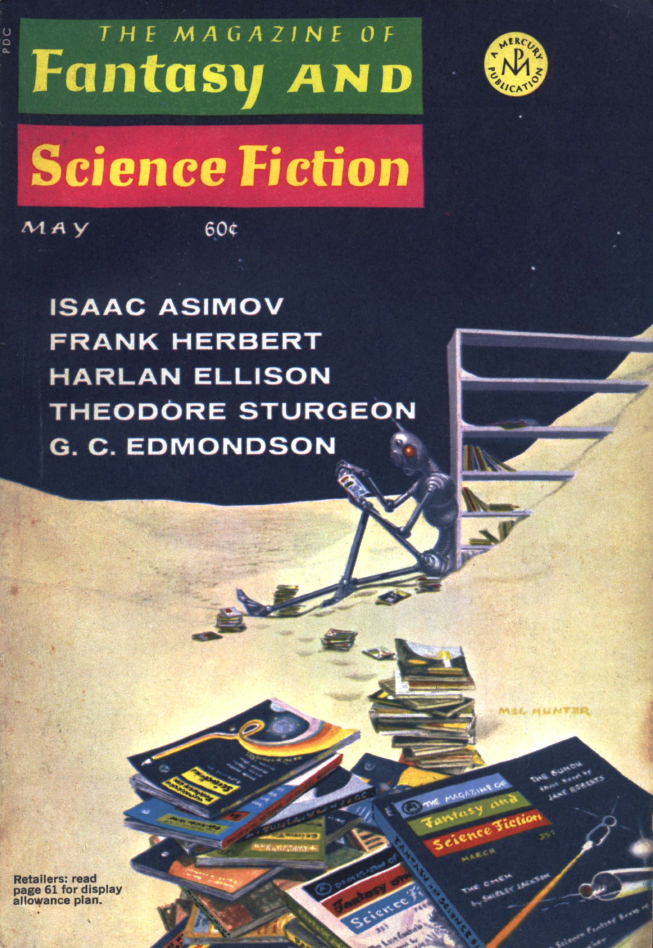

This came in last year’s festive themed issue of F&SF. To most people, Kris Kringle is a jolly fellow who makes toys, however he lives a double-life as a secret agent. He is brought in to bring down an extra-terrestrial threat taking over America’s top politicians, known only as S.P.I.D.E.R.

Joke stories are always going to be subjective. Whilst I understood the satirising going on, it didn’t really appeal to my sensibilities.

Two Stars

Try a Dull Knife

Continuing with Fantasy & Science Fiction, this one was published there in October. The internal thoughts of an empath as he decries his lot.

Standard mid-level Ellison.

I am with our editor on the rating of Three Stars.

The Pitll Pawob Division

From the December issue of If, it tells the story of an encounter with a strange egg.

Honestly just feels empty, over-described and lacking substance.

One Star

The Place with No Name

This one was only just published in last month’s F&SF. In order to escape from the law, Norman Mogart accepts a mission from an indescribable entity, which will involve him travelling into the jungle to a place with no name.

Not quite one that I would have expected from Ellison, instead what Philip K. Dick might have written for 1930s Weird Tales. Whilst a little odd, it still had a strong sense of atmosphere that pulled me along.

I agree with our esteemed editor’s ranking of Four Stars.

White on White

Apparently, this one was previously published in men’s magazine Knight, but is certainly new to me. I was also initially confused if it was meant to be linked to the prior story (but I do not believe so).

A gigolo is staying with the Countess on the Aegean when she decides to climb a mountain. Going to the top he finds a surprising example of true love.

A vignette lower on SF and high on taboos. Reminds me of the weaker stories in recent issues of New Worlds.

One Star

Run for the Stars

For the next few we are jumping back to the earlier days of Harlan’s career, with this tale from 1957. Earth is at war with the Kyban empire. Talent, a drug addict, is forced by the resistance into a desperate gambit to defeat the alien invaders. To be turned into a human bomb.

This is the second longest piece in the collection but it took me the longest to read because I found I would keep losing interest and just skim read over sections. It is not terrible and asks some interesting questions, but it is too long and his style is yet to mature.

Two Stars

Are You Listening?

I was surprised to see this 1958 story here as you can still get it in Earthman Go Home (the paperback title for Ellison Wonderland). Albert Winsocki wakes up one day to discover that people can no longer see or hear him, what has happened?

Ellison does good work creating the atmosphere of panic here, however the point is made very clumsily. Not one of his better works.

Three Stars

S.R.O.

We are finishing our late 50s trilogy with this tale from 1957’s Amazing. An alien spaceship lands in the middle of New York. But rather than invading, they appear to simply want to put on a show. Of course, there are always people on hand to make money from such an opportunity.

Similar to the previous tale, Ellison creates a good atmosphere but the points being made are nowhere near as skilful. Enjoyable in a 50s Galaxy kind of way.

Three Stars

Worlds to Kill

Back to more recent tales, with this one from If in March 1968. It follows crippled mercenary Jared and his battles around the universe.

As you would expect from Ellison, this is not John Carter of Mars. Instead, it is a dark and cynical take on the universe. It doesn’t quite have enough meat on its bones for me but is still pretty good.

Three Stars

Shattered Like a Glass Goblin

I reviewed this short less than a year ago when it first appeared in Orbit 4. To repeat my summary:

Rudy has finally gotten out of the army on medical, only to find his fiancée Kris in a marijuana-drenched squat in downtown LA. Is he just not “with it” anymore? Or is something more sinister going on?

This won a Galactic Star so clearly many of my fellow Journeyers believe it is a five-star story. Personally I am keeping it at Four Stars.

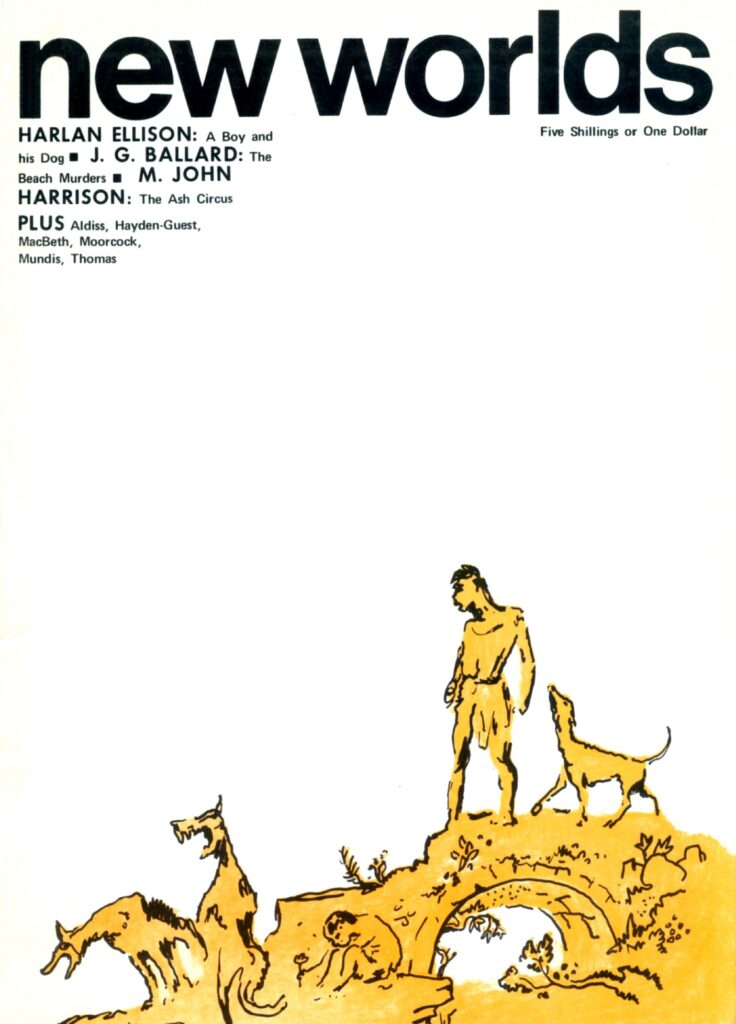

A Boy and His Dog

By far the longest story in the collection is an expansion of the novelette version published in New Worlds recently. In a post-nuclear world, a boy, Vic, and his canine meet a young woman, Quilla, and follow her to a secret underground city.

There is no real difference in the story other than verbosity. To take one example, here is the New Worlds text:

Blood and I crossed the street and came up in the blackness surrounding the building, it was what was left of the YMCA.

And here is the unedited text in this collection:

Blood and I crossed the street and came up in the blackness surrounding the building. It was what was left of the YMCA.

That meant “Young Men’s Christian Association”. Blood taught me to read.

So what the hell was a young men’s christian association. Sometimes being able to read makes more questions than if you were stupid.

The full text adds slightly more texture to the world but does not actually advance anything. So it probably depends if you like even more Harlan for your buck or prefer him in small doses.

Personally, I give both versions Four Stars.

So, whilst it may be Ellison’s biggest collection, these are not necessarily his best stories. What it does do well is it shows his range, from simple didacticism to the obscure. From only marginally SFnal tales to alien wars. Maybe he has a point that he isn’t just an avant-garde new wave sci-fi writer?

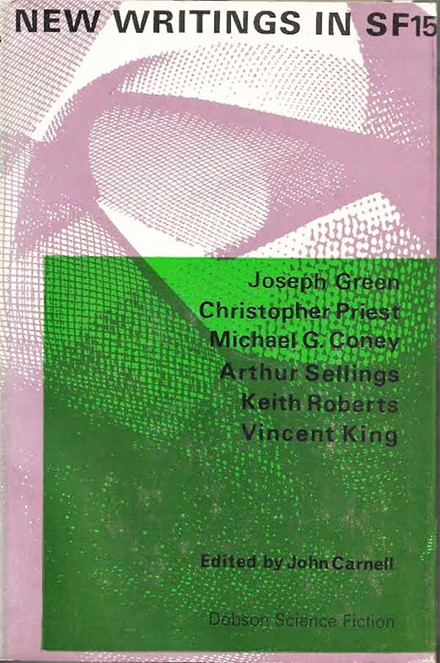

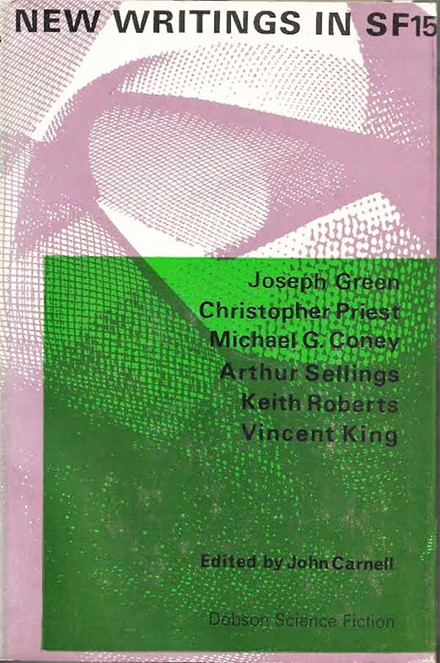

New Writings in SF-15, Ed. By John Carnell

With more volumes than many monthly magazines manage, New Writings continues on. This time the theme is psychological. How do Carnell’s crew deal with this one?

Report from Linelos by Vincent King

Probably my favourite writer from these pages returns with a more experimental story than usual. These are the tapes of two consciousnesses:

Consciousness A: The internal monologue of an energy being that believes itself to be a God

Consciousness B: A tale of Linelos, a strange world where Arthurian knights go on quests with machine guns, dodging napalm dropped from biplanes.

What do these two narratives have to do with each other? And what could they mean?

I am always happy to see authors stretch themselves. King continues with his trademark medieval-futurism but adds new stylistic touches to it. And even though the explanation at the end combines two of the standard twists of the genre, he does so elegantly, such that I did not suspect them before I was told.

Five Stars

The Interrogator by Christopher Priest

Whilst this young fan had appeared in a couple of issues of Impulse he recently declared his intention to focus on professional writing. If this story is anything to go by, he has a good career ahead of him

Dr. Elias Wentick was stationed in the Antarctic when a mysterious government man named Astroude approached him about identifying a strange jet fighter. Now he finds himself in an otherwise empty prison. He will occasionally be interrogated, with Astroude wanting the answer to apparently pointless questions.

As you can probably tell this draws a lot from Darkness at Noon and The Trial, but it has a great atmosphere and enough original touches to stand out.

A high four stars

When I Have Passed Away by Joseph Green

Green has been writing for the US magazines for the last few years; nice to see him back here.

At Outworld University on Earth, two humans, Halak and Caal, had become inseparable from two She’waan, Phe’se and Princess Sum’ze. One day, the two She’waan abruptly leave without explanation. Four years later, Caal receives a message from Sum’ze (now Queen) that she desperately needs his help.

With Phe’se’s help they work in secret on the matriarchal world of Achernar Six. All She’waan women over thirty transform into gaseous clouds, a fate Halak and Caal are determined to save Phe’se from. However, as Queen Sum'ze lies dying, different factions are fighting to claim the throne for themselves.

This is the briefest summary I can manage to give of this tale but there is a lot more going on. It represents a fascinating combination of old and new. I was really impressed with the sense of wonder Green manages to evoke, reminiscent of Clark Ashton Smith, and it involves a number of concepts from the pulp era. However, it is also focussed on the development of women’s bodies and works as an interesting metaphor on how women of a certain age are treated by society at large.

Four Stars

Symbiote by Michael G. Coney

To the best of my knowledge this is a debut piece from Coney, presaging what I hope will be a great career.

On an alien world the humans find the Chintos, monkey-like creatures that become incredibly popular as pets on Earth. Soon everyone has one riding on their shoulders. Centuries later humans have become like beasts of burden for their host Chintos, who now do all the thinking and humans all the movement. We follow census taker Joe-Tu as they arrive in a village that is faced with flooding.

This marks an interesting reversal of some conventional concepts of SFnal storytelling. Firstly, instead of humanity’s bodies being diminished by machines, it is our minds as that are diminished as the Chintos do our thinking for us and we simply play. Secondly, the Chintos are not parasitic invaders, but a result of mankind’s folly who feel sorry for and want to help us. The ending is a little weaker than I would like, but the piece is a very good first effort.

Four Stars

The Trial by Arthur Sellings

The late great author apparently still has a few stories left to be published. In this future the Galactic Council, largely run by Earth, controls many worlds. The only rivals to their power they have found are the Vyrnians, gangly purple humanoids nicknamed Hoppos. When one Vryn is arrested and put under a truth drug, he reveals himself to be a missing human space captain and is put on trial for treason. But how did this happen? And why?

This is a fascinating piece critiquing colonialism; however, your enjoyment of this will probably depend on how much you like courtroom dramas. Thankfully, I find great pleasure in them.

Five Stars

Therapy 2000 by Keith Roberts

Since the collapse of Science Fantasy/Impulse, the former sub-editor has remained largely absent from the SF scene. Even if he is not always my favourite author, it is nice to see him back.

In a world filled with noise, ad man Travers is obsessed with trying to remove auditory sensation from his life, even to the extent of damaging his ears and angering everyone around him.

I personally suffer when there is an intensification of external stimuli so I related to the character of Travers. Whilst this story posits a future where the silence is only available to the rich, in modern metropolitan life it can still be hard to find five minutes of peace and quiet. Roberts is able to show that very well with his vivid descriptions. One of his better works.

Four Stars

And so another New Writings triumph under Carnell’s belt. Like the sunny weather we have been experiencing, long may it continue.

![[August 4, 1970] Through the Wasteland (Harlan Ellison's <i>the Glass Teat</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/700804teatcover-672x372.jpg)

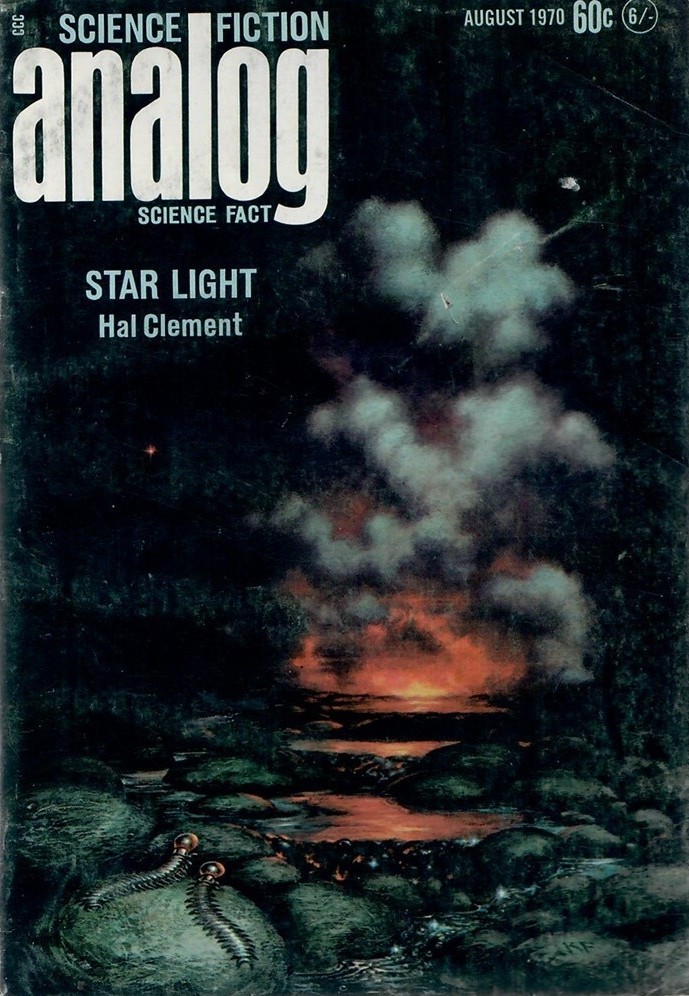

![[July 31, 1970] Not so Brillo… (August 1970 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/700731analogcover-672x372.jpg)

![[April 20, 1970] Not the final quarry (May 1970 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/700420fsfcover-653x372.jpg)

![[February 8, 1970] Boldly going to the Region Between (March 1970 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/700208galaxycover-653x372.jpg)

![[December 24, 1969] At Last The 1980 Show: <i>New Worlds</i>, January 1970](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/NW19701-cover-672x372.png)

None of the photos I took turned out, but here's the art for the poster.

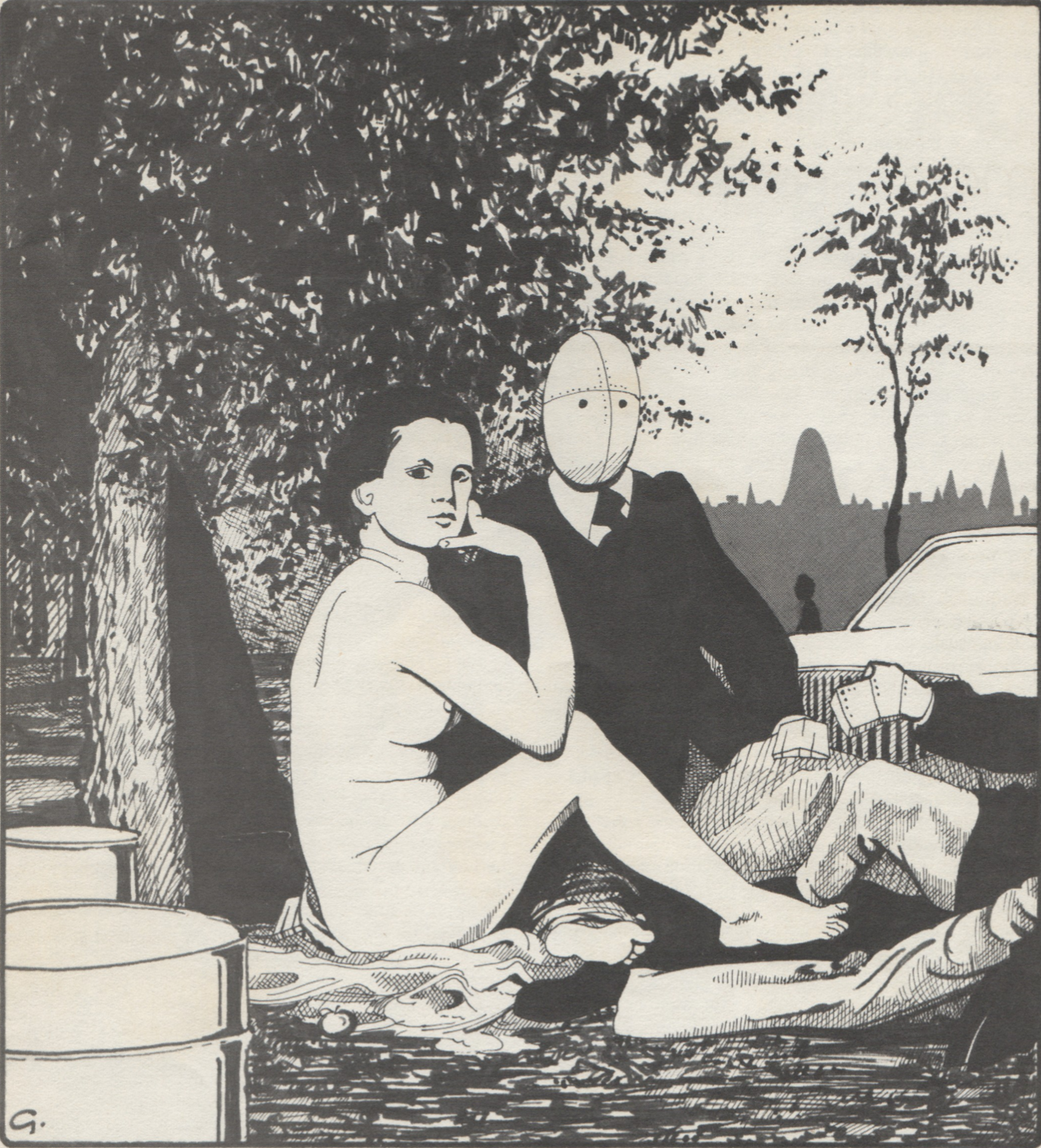

None of the photos I took turned out, but here's the art for the poster. Cover by R. Glyn Jones.

Cover by R. Glyn Jones. Illustration by Charles Platt.

Illustration by Charles Platt. Illustration by R. Glyn Jones, who gets everywhere this issue.

Illustration by R. Glyn Jones, who gets everywhere this issue. Photo by Gabi Nasemann.

Photo by Gabi Nasemann. Design by unknown artist.

Design by unknown artist. Photo by Roy Cornwall.

Photo by Roy Cornwall. Illustration by Charles Platt.

Illustration by Charles Platt. Illustration by Pam Zoline.

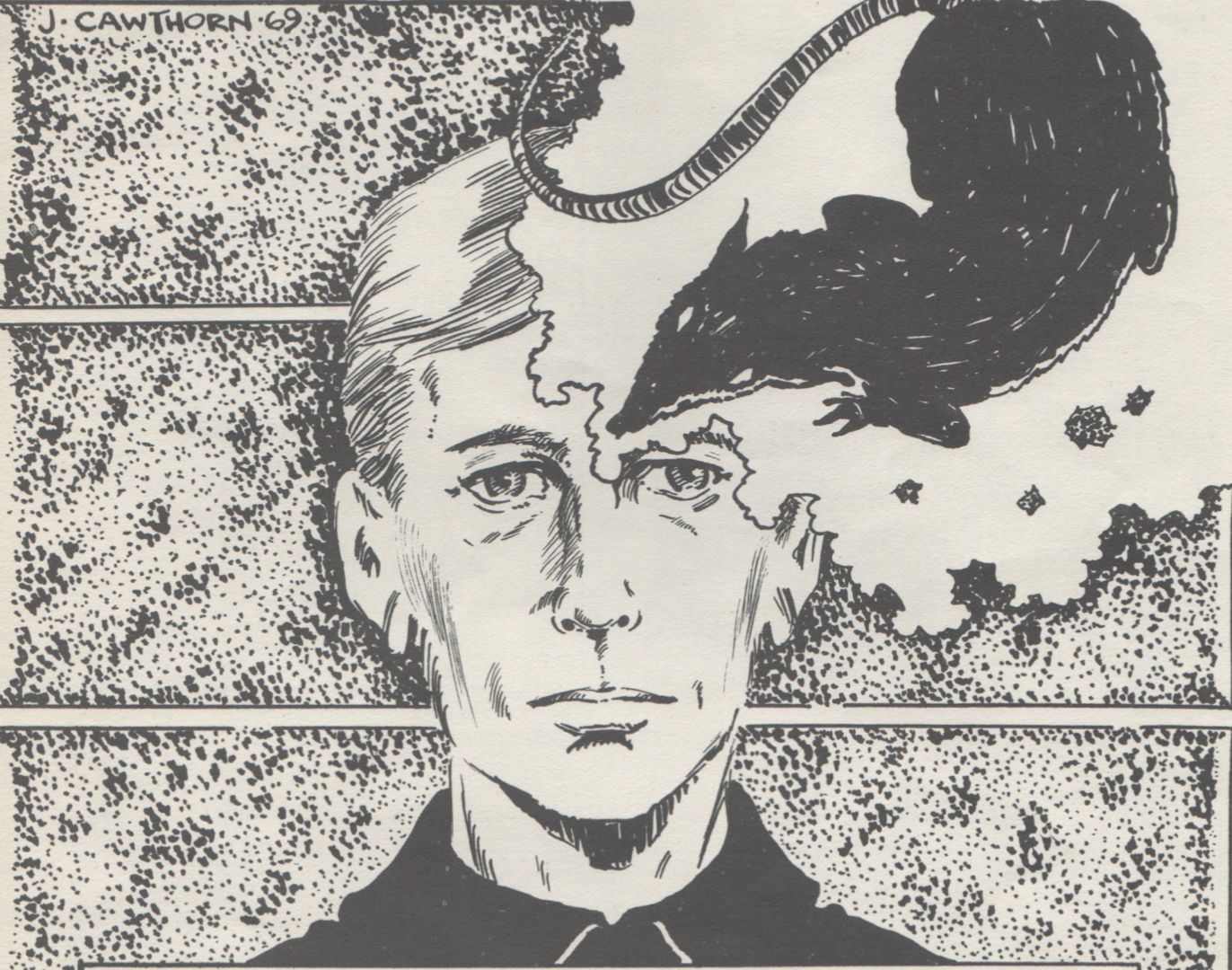

Illustration by Pam Zoline. Illustration by James Cawthorn.

Illustration by James Cawthorn. Photo by Roy Cornwall.

Photo by Roy Cornwall.

![[October 12, 1969] My country, right or… (November 1969 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/691010cover-460x372.jpg)

![[September 22, 1969] Unsmoothed curves (October 1969 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/690922fsfcover-658x372.jpg)

![[July 22, 1969] Let The Sunshine In (More July Books)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/690722covers-672x372.jpg)

![[June 20, 1969] Where to? (July 1969 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/690620fsfcover_jpg-438x372.jpg)

![[March 24, 1969] Apocalypse Impending? <i>New Worlds</i>, April 1969](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/New-Worlds-April-1969-672x372.jpg)

The named list from last month.

The named list from last month. Cover by Mervyn Peake.

Cover by Mervyn Peake. In a post-apocalyptic US we are told of teenager Vic and his telepathic dog, Blood. Vic is a teenage boy who spends his time scavenging the world for basic needs—food, companionship, and sex—as well as generally avoiding other groups, known as roverpaks, doing the same thing. They meet Quilla June – unusual because most women live where it is safer, underground. Vic rapes Quilla June before they are attacked by another roverpak. Blood is hurt in the scuffle. Quilla June escapes and returns to her underground home of Topeka.

In a post-apocalyptic US we are told of teenager Vic and his telepathic dog, Blood. Vic is a teenage boy who spends his time scavenging the world for basic needs—food, companionship, and sex—as well as generally avoiding other groups, known as roverpaks, doing the same thing. They meet Quilla June – unusual because most women live where it is safer, underground. Vic rapes Quilla June before they are attacked by another roverpak. Blood is hurt in the scuffle. Quilla June escapes and returns to her underground home of Topeka.

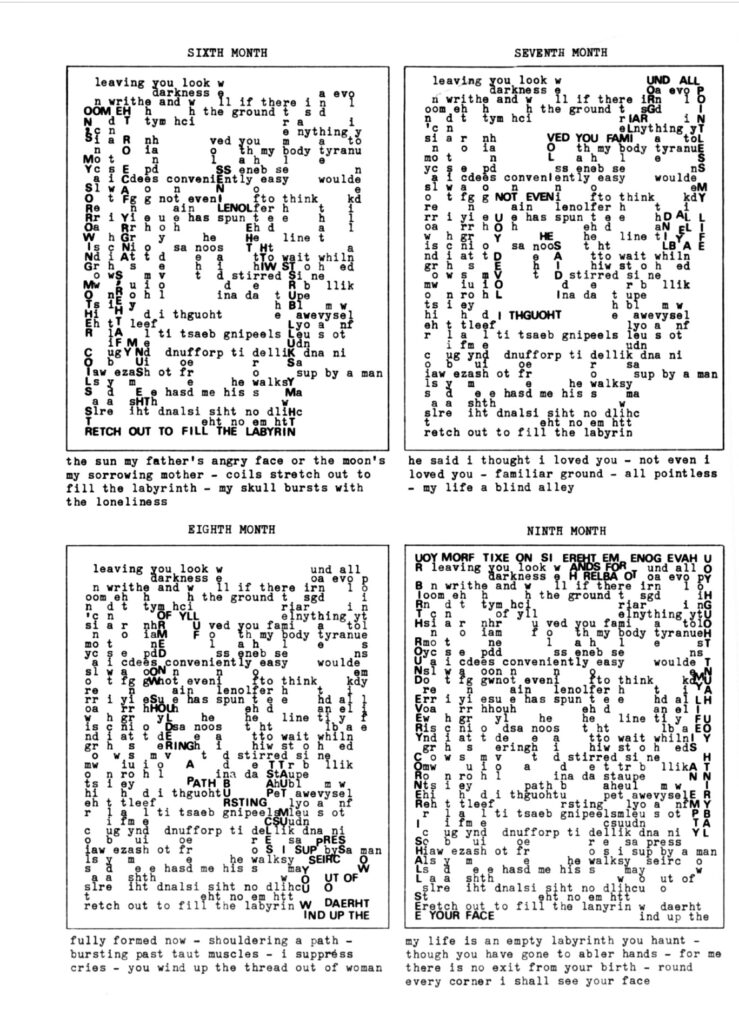

More poetry. Described as ‘a poem for light and movement’, Thomas manages to produce strange typewritten boxes that are at times undecipherable. A typical ‘form over content’ type piece. 2 out of 5.

More poetry. Described as ‘a poem for light and movement’, Thomas manages to produce strange typewritten boxes that are at times undecipherable. A typical ‘form over content’ type piece. 2 out of 5. The inevitable 'naked lady of the month' picture.

The inevitable 'naked lady of the month' picture. Artwork by Mal Dean.

Artwork by Mal Dean. More artwork by Mal Dean.

More artwork by Mal Dean.