by John Boston

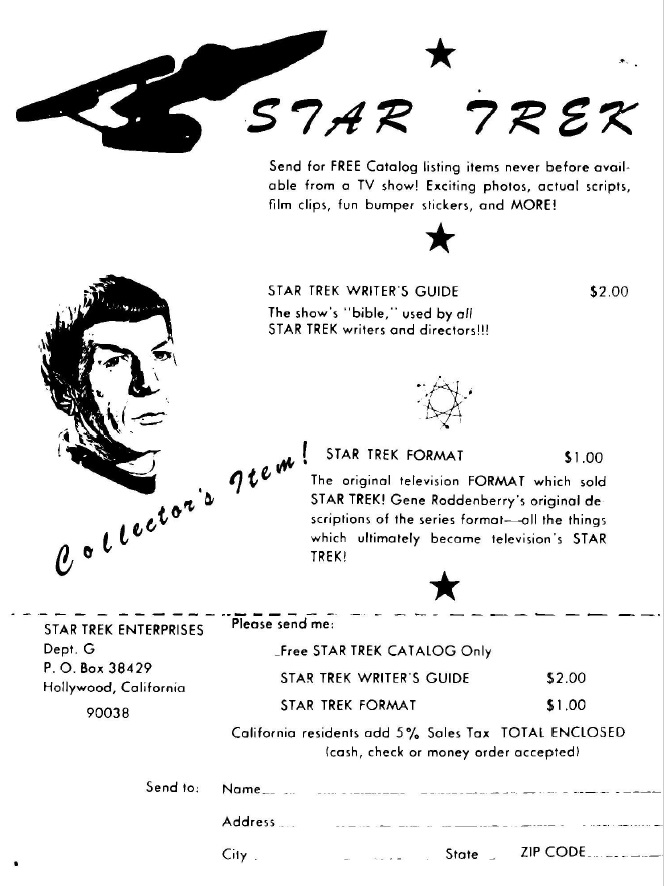

The February 1968 Amazing, the second under Harry Harrison’s editorship, displays two themes on its face, both noted last issue. The first is puffery: this issue says WORLD’S LEADING SCIENCE-FICTION MAGAZINE at the top of the cover, which also boasts “Katherine MacLean’s outstanding new novelet,” and the table of contents lists this “New Outstanding Novelet,” a “Classic Novelet,” and a “Special Novelet.” The second theme is protesting-too-much discomfort with the mostly-reprint fiction policy, evidenced by the prominent display of “New” on the cover: MacLean’s “Outstanding New Novelet,” “New Features,” “New Article,” “New Frank Herbert Novel.”

by Johnny Bruck

But there’s a third, more substantive theme: commendable initiative in the small amount of space left open by the reprint policy. The “New Features” listed on the contents page include the first of a promised series of articles on the “Science of Man,” by Leon E. Stover, an anthropologist now at the Illinois Institute of Technology. The book review column features a long and interesting essay-review by Fritz Leiber of a translation of a book by French author Claude Seignoll, with comments about the state of Gothic fiction generally. (See below concerning both of these.) There is also the London Letter, said to be the first of a series to include a Milan Letter, a Munich Letter, etc. This one is by Harrison’s pal Brian Aldiss, and it amounts to an extemporaneous stand-up routine which probably took Aldiss 20 minutes to write. Parts of it are amusing.

These items are all touted by Harrison in his editorial, but they are not his main matter; the editorial is titled Amazing and the New Wave, and its first half amounts to a disappointingly smarmy exercise in having it both ways:

“There is no New Wave in science fiction. Or, to put it another way, Amazing is the New Wave. . . . Science fiction is the new wave that washed into existence in 1926 with the first issue of the magazine. . . .

“To me there are only two kinds of science fiction: the good and the bad. . . . It is exactly what it says it is, and it is what I happen to be pointing to when I say the magic words ‘science fiction.’ And that is all the definition you are going to get out of me.

“The present New Wave is therefore two things: it is bad SF and it is good SF. When bad it should be consigned to the nether cellars of our building with the rest of the cobwebbed debris of the years. When it is good there are plenty of rooms it can slip into and feel comfortable.”

So Harrison spends a page on a subject of current controversy while ostentatiously saying nothing of substance about it. This banal babble from an otherwise obviously intelligent editor is presumably his way of trying to ingratiate himself and the magazine with everyone while offending no one—a bad idea that will fool nobody and which one hopes is not repeated.

Meanwhile, the actual fiction content of the magazine, except for the above-average serial, is more or less what it has been since the departure of Cele Lalli and the advent of Sol Cohen.

Santaroga Barrier (Part 3 of 3), by Frank Herbert

Frank Herbert’s serial Santaroga Barrier, begun under the previous editor, concludes in this issue, and exits honorably. To begin, the protagonist Gilbert Dasein, who teaches psychology at Berkeley, is driving to the isolated and reclusive California town Santaroga, hired by an investment company wanting to know why their chain stores were forced out of town. In Santaroga, there is no reported juvenile delinquency or mental illness. Cigarettes are purchased only by transients. Nobody moves away; servicemen always return there upon discharge; and outsiders find no houses for rent or sale. Jenny, Dasein’s not-so-old flame, moved back to Santaroga when she finished at Berkeley, telling him she couldn’t live anywhere else. (The profs fooling around with the students? Shocking!) There’s a dominant local industry, the Jaspers Cheese Cooperative, but it doesn’t produce for the outside market—the stuff “doesn’t travel.” Also, Dasein is the third investigator sent to Santaroga, the two predecessors having sustained accidental deaths.

by Gray Morrow

These cards dealt, Dasein arrives at the town’s sole inn, where he tries to call his handler in Berkeley, but the line goes out, and stays out afterwards. He is then overcome in his room by a leak from an old gas jet, and rescued just in time. Jenny, alerted to his presence, and seemingly very happy about it, shows up with breakfast. It turns out she never received the letters he sent her after her return.

Dasein quickly learns that everyone seems to know who he is. He encounters new manifestations of the town’s insularity. Nobody has TV, except for a hidden room full of people whose job it is to monitor it. There’s a local newspaper, but it’s subscription only, and its concept of reporting the news is unusual: “Those nuts are still killing each other in Southeast Asia.” All commerce appears to be local. Dasein also learns that Jaspers is not just a brand name, but a substance, one which is near-omnipresent in food and drink. And he notices a “vitality and a happy freedom” in the movements of people on the streets.

Meanwhile, the Jaspers (which is referred to later as “consciousness fuel”) is having an effect on him (“he had never felt more vital himself”), which he doesn’t entirely grasp. He’s getting a little deranged, though hardly without cause, since he also keeps having near-fatal accidents—tripping over a carpet and being narrowly saved from a three-floor fall; a kid absent-mindedly loosing an arrow that barely misses him; a garage car lift collapsing; a waitress unknowingly poisoning his coffee; and more. As for his derangement, shortly after the carpet incident, still suffering from a sprained shoulder, he takes a dangerous nighttime climb down into the Jaspers factory, clambering down and through its ventilation shafts despite his injury. Eventually he is questioning his own sanity.

It becomes apparent that consumption of Jaspers has created some sort of shared consciousness among the Santarogans, though Herbert remains vague about exactly how it works. The people responsible for his “accidents” (poisoning his food, shooting an arrow at him) seem not to have consciously intended harm, but to have unknowingly acted out the hostility and fear of the Jaspers collectivity. (Monsters from the id!) Jenny hysterically acknowledges that phenomenon: “Stay away from me! I love you! Stay away!”

Dasein also begins to see some less attractive features of the Jaspers-permeated community. On his first visit to the Jaspers factory, he finds that Jenny—trained as a clinical psychologist—works on the inspection line. Leaving, he sees through a door left open a line of people with their legs in stocks doing menial work, “oddly dull-eyed, slow in their actions.” He later learns these are the people who flunked the Jaspers initiation—about one in 500. After wondering where all the children are, he finds them working in the greenhouses, marching and chanting. Dr. Piaget, the designated spokesperson for the Santaroga way, says: “We must push back at the surface of childhood. . . . It’s a brutal, animate thing. But there’s food growing. . . . There’s educating. There’s useful energy. Waste not; want not.”

At this point, Herbert’s thriller has become a philosophical novel, or at least a novel about philosophies. Dr. Piaget elaborates on Santaroga’s child rearing practices, which reflect Santaroga’s departure from the usual human understandings about everything: “We take off the binding element. Couple that with the brutality of childhood? No! We would have violence, chaos. . . . We must superimpose a limiting order on the innate patterns of our nervous systems.” Hence, child labor; got to get 'em disciplined early."

Dr. Piaget continues: “We know the civilization culture-society outside is dying. They do die, you know. When this is about to happen, pieces break off from the parent body. Pieces cut themselves free, Dasein.” And Dasein acknowledges the obvious: “Dasein knew then why he’d been sent here. No mere market report had prompted this. . . . He was here to break this up, smash it.” Piaget again: “Contending is too soft a word, Dasein. There is a power struggle going on over control of the human consciousness. We are a cell of health surrounded by plague. . . . This isn’t a struggle over a market area. . . . This is a struggle over what’s to be judged valuable in our universe.”

There is more denunciation of “outside” (another character says, with elaboration, “it’s all TV out there”), and much ambivalence on Dasein’s part about both outside and Santaroga, resolved in a final confrontation when the man who sent him to Santaroga comes looking for him.

This is a pretty solid SF novel, much better than Herbert's previous serial The Heaven Makers, with an interesting if somewhat vague idea capably revealed through a plot dense with incident, though there are minor points where things don’t hang together well. Though talky, it’s much less of a turgid slog than some of his other work (Ahem, Dune). The hive-mind idea is not entirely original, but Herbert takes a different angle and asks different questions than some of his predecessors. In fact, the novel can be viewed almost as the anti-More Than Human—do you really want to give up your individuality and privacy for the comfort of such close and inescapable community? Especially when you might end up acting violently without even realizing it? Four stars, with a couple of planetoids thrown in.

Note the portentousness of some of the names in this novel. An SF fan’s first thought about Gilbert Dasein is likely that it’s homage or satirical swipe at Gilbert Gosseyn, protagonist of van Vogt’s The World of Null-A. But that’s probably wrong. “Dasein” is German philosopher Martin Heidegger’s term for existence, as it is experienced by human beings. Karl Jaspers is another German philosopher. Jean Piaget is a Swiss psychologist famous for his studies of child development, some of whose work looks as much like philosophy as psychology. A student of philosophy, which I am not, might make something of these names, but I’d suggest that the novel works well enough without that kind of gloss.

The Trouble with You Earth People, by Katherine MacLean

by Jeff Jones

Katherine MacLean contributed a number of incisive stories to the SF magazines from 1949 into the early ’50s (Defense Mechanism, —And Be Merry, Incommunicado, Contagion, etc.), and a few since then (mainly Unhuman Sacrifice). Her novelet The Trouble with You Earth People isn’t on that level; it’s an amusing and mildly bawdy story of cultural misunderstanding between doggish alien visitors, whose understanding of humanity is based on watching television, and an easily scandalized elderly scientist. It reads like it could have used another draft. Three stars.

Remote Control, by Walter Kateley

To the reprints. Walter Kateley’s Remote Control (from Amazing, April 1930), opens with the narrator’s friend Kingston showing him around a large construction project. It is being carried out by animals—whales and sharks carrying heavy freight, apes and elephants unloading it, and as for the typing and computation required for such a project: “The machines were being operated at lightning speed, not by lady typists, as one might expect, but by bushy-tailed gray squirrels!”

by Hans Wessolowski

The author now flashes back to an earlier time, when Kingston has joined the narrator on his family farm, and assists with his observations of ants. The two are puzzled by the ants’ efficiency in carrying out cooperative tasks without anything much resembling a brain and with no indication of how their activities are coordinated. Then an accidental mixture of buttermilk and cedar oil gets on one of their lenses, and—revelation! Now they can see tiny bright lines of energy leading from the ants back into the nest, which when followed to their source reveal a tiny brain that is apparently coordinating all their activity. The possibilities are obvious, and it’s a short hop from these naturally manipulated ants to whales and elephants working construction, with squirrels on typewriters in the office, and human puppet masters somewhere off premises.

This one is amusing at first, but quickly gets tedious, since the story consists mostly of Kingston and narrator lecturing each other, with the narrator at one point reading aloud a passage from his favorite entomology text. Fortunately this “novelet” runs only 18 pages of large print and is over quickly. Two stars.

"You'll Die Yesterday!", by Rog Phillips

Rog Phillips’s “You’ll Die Yesterday!” (from the March 1951 Amazing) is a piece of yard goods by one of Ray Palmer’s stable of hacks—but a pretty capable one. Phillips published some 44 stories in a little over six years before this one, mostly in Amazing and Fantastic Adventures, and clearly has the knack to meet Palmer’s famous editorial demand to “gimme bang-bang.” Protagonist Stevens, author of a successful book, is giving a lecture; an audience member asks a question but is shot before Stevens can answer; the killer runs out of the auditorium but inexplicably disappears. Before the cops arrive, Stevens swipes some papers carried by the decedent, Fred Stone, and shows by home carbon-dating that they are from the future. Also, Stone was carrying a “T.T.” permit (figure it out) and a printed copy of Stevens’s speech, which was extemporaneous, so it could only have been prepared later from a transcript. Next day, Stevens’s girlfriend sees Stone, alive, on the street. Turns out his body is missing from the morgue.

by Julian S. Krupa

More developments come thick and fast and there’s a revelation at the end which actually doesn’t resolve much, but might seem to if the reader wasn’t paying close attention, as I suspect was the case with much of the Palmer Amazing’s readership. So it’s a clever if insubstantial riff on the time paradox theme. Three stars for good workmanship.

The Great Invasion of 1955, by David Reid

The Great Invasion of 1955, by David Reid, from the October 1932 Amazing, is another tedious old story in which the Japanese are invading the United States and are vanquished by new technology based on now out-of-date science. It may be of interest to those interested in speculative helicopter design. Otherwise, one star.

Turnover Point, by Alfred Coppel

Alfred Coppel, author of Turnover Point (Amazing, April-May 1953), helped fill the SF pulps and lower-echelon digests with mostly forgettable material from the late ‘40s until the mid-‘50s, when he disappeared from the genre, briefly reappearing in 1960 with the well-received post-nuclear war novel Dark December. This story is a bucket of cliches—a Bat Durston, i.e. a displaced Western—which is a surprise, since it appeared in the first issue of the magazine’s brief flirtation with high pay rates and higher quality content. But here it is, alongside Heinlein, Sturgeon, and Bradbury. A sample:

“The Patrol was on Kane’s trail and the blaster in his hand was still warm when he shoved it up against Pop Ganlon’s ribs and made his proposition.

“He wanted to get off Mars—out to Callisto. To Blackwater, to Ley’s Landing, it didn’t matter too much. Just off Mars, and quickly. His eyes had a metallic glitter and his hand was rock-steady. Pop knew he meant what he said when he told him life was cheap. Someone else’s, not Kane’s.”

by Ed Emshwiller

The bad guy hiring Pop’s battered old spaceship turns out to be the one who killed Pop’s son, a Patrol officer who “was blasted to a cinder in a back alley in Lower Marsport.” Pop knows Kane is going to kill him after “turnover point”—the point at which the spaceship is turned around (a maneuver accomplished with a flywheel) so its business end faces the destination for deceleration and landing. But Pop has the last laugh—he didn’t turn the ship around to decelerate for landing, but made a full 360 degree turn, so it continues on towards the outer reaches of the solar system, where Kane can starve, suffocate, and go crazy after it is too late to do anything about it. Whoopee! Two stars, barely, since it’s at least capably written for what it is.

Science of Man: Neanderthals, Rickets and Modern Technology, by Leon E. Stover

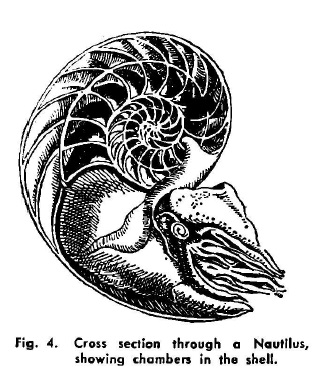

Prof. Leon Stover’s article suggests that the Neanderthals died out because they wore clothes, shielding themselves from sunlight and therefore from vitamin D. Vitamin D deficiency causes rickets, which has serious enough consequences to affect evolutionary success. Clothing was the Neanderthals’ technological solution to the glaciation of their habitat; what saved them then killed them off. Vitamin D absorption, or lack of it, also accounts for the distribution of races: dark skin absorbs less than light skin, so dark-skinned peoples flourish in the tropics where there’s a surfeit of sunlight, while light-skinned people dominate at higher latitudes. The moral: people must assess the consequences of their technological development, as the Neanderthals failed to, and we need a lot more technically trained people than we’ve got.

It all seems plausible and is lucidly enough written. Is he right? Beats me. Three stars.

The Future in Books

Ordinarily I don’t rate the book review columns, but this one is unusual, containing Fritz Leiber’s review of French writer Claude Seignolle’s The Accursed: Two Diabolical Tales. Leiber traces the current revival of “Gothic” fiction, recognizable by the paperback covers depicting an anxious-looking woman, with a large house in the background displaying a single lighted window, and notes the less formulaic older books being reprinted under cover of this new wave (excuse the expression) of yard goods.

This brings us to Leiber’s typology of “the true Gothic or supernatural-horror story,” of which there are two flavors: “Can such things be?” and “Such things are! So let’s go whole hog!” He continues: “The first type of story aims to make a sensitive, intelligent reader question for a deliciously scary moment the stable, science-proved foundations of the world in which he trusts. The second provides a feast of grue for those who relish such banquets.” Seignolle’s two novellas (one featuring a young pyrotic, the other a young lycanthrope) are firmly in the second camp, as Leiber shows by judicious description and quotation.

This is all lively and informative, above and beyond the usual book review, though Leiber disappointingly fails to describe where Seignolle’s work fits into the fantastic tradition (or lack of it) in his native France. Also, the book is introduced by Lawrence Durrell, a rather large noise in contemporary literature after his Alexandria Quartet; Leiber does not mention what Durrell has to say about the book, or about Seignolle generally. So, three stars; a good piece that should have been better. (And this rating in no way reflects the other review here, a distasteful hit job on Roger Zelazny’s Lord of Light bylined “Leroy Tanner,” well known as a pseudonym of Harrison’s.)

Summing Up

So, a good novel (though one begun under the previous regime), a decent new story, the usual uneven bunch of reprints, and some stirrings of life in the non-fiction departments. I’m not sure that adds up to “promising”—more like “steady as she goes”—so we’ll have to leave it with a version of the baseball fans’ lament: “wait till next issue.”

![[October 20, 1968] Giants among Men (November 1968 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/681020cover-672x372.jpg)

![[October 8, 1968] Probing the future (November 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/681008cover-672x372.jpg)

![[June 6, 1968] The Stalemate Continues (July 1968 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/amz-0768-cover-496x372.png)

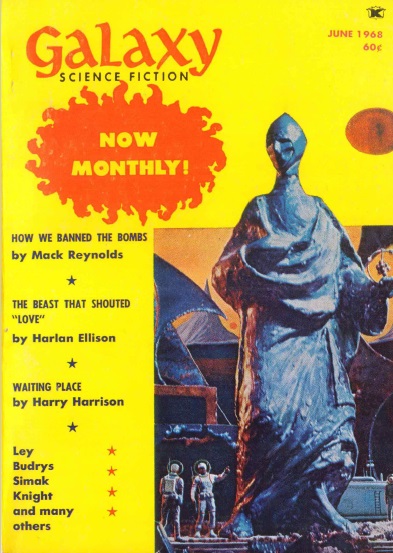

![[May 10, 1968] Horse race (June 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/680510cover-393x372.jpg)

![[April 12, 1968] Darkness (May 1968 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/SMALLCOVER-672x372.jpg)

This tale appeared in the December 1956 issue of the girlie magazine Caper, attributed to Spencer Strong (Ackerman again) and Morgan Ives (Marion Zimmer Bradley.)

This tale appeared in the December 1956 issue of the girlie magazine Caper, attributed to Spencer Strong (Ackerman again) and Morgan Ives (Marion Zimmer Bradley.)

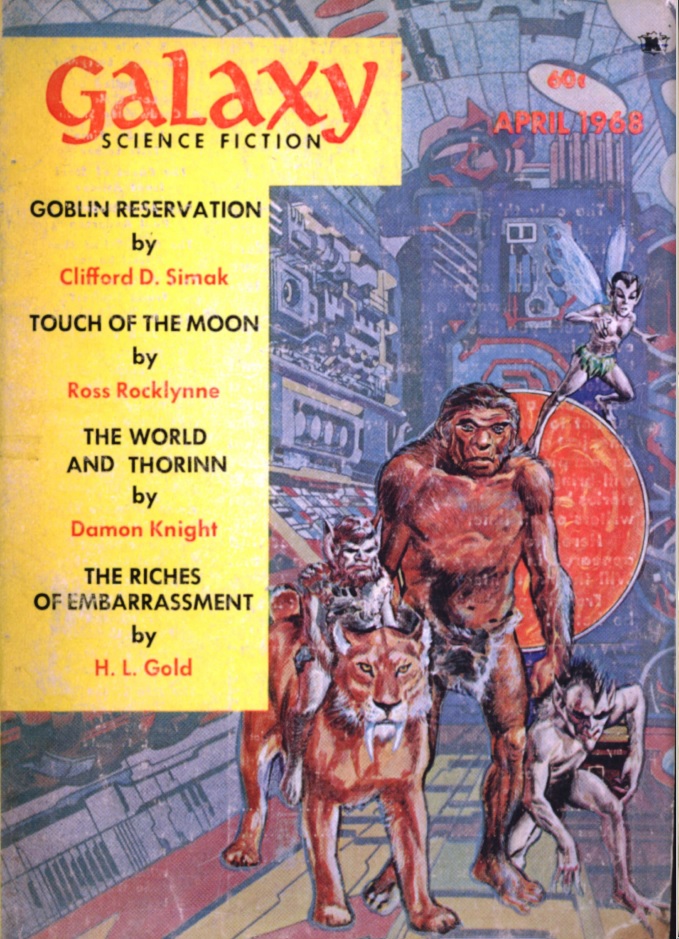

![[March 6, 1968] Trend-setter (April 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/680306cover-672x372.jpg)

![[March 2, 1968] Rules and Regulations (April 1968 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/IF-1968-04-Cover-639x372.jpg)

The stars of the show. (l.) Jean-Claude Killy sporting his medals. (r.) Peggy Fleming in her spectacular performance.

The stars of the show. (l.) Jean-Claude Killy sporting his medals. (r.) Peggy Fleming in her spectacular performance. The Advanced Guard prepare to study the fauna of Chryseis. Art by Vaughn Bodé

The Advanced Guard prepare to study the fauna of Chryseis. Art by Vaughn Bodé![[January 16, 1968] Worthy programming (February 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/680110cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 14, 1968] As Is (February 1968 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/amz-0268-cover-492x372.png)

![[January 2, 1968] The consequences of success (February 1968 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/IF-1968-02-Cover-672x372.jpg)

Louis Washkansky talks to Dr. Barnard in the days following the surgery.

Louis Washkansky talks to Dr. Barnard in the days following the surgery. This dreamscape doesn’t appear in Robert Sheckley’s new story, but it could. Art by Vaughn Bodé

This dreamscape doesn’t appear in Robert Sheckley’s new story, but it could. Art by Vaughn Bodé