by Victoria Silverwolf

Departures and Arrivals

One of the more intriguing events this month was the death of a celebrity, although not one you're likely to see in the obituary column. A tortoise known as Tu'i Malila (meaning King Malila in the Tongan language, although she was female) died on the sixteenth of May. Why is this notable? Well, they say she was one hundred and eighty-eight years old, a ripe old age, even for a tortoise.

The story goes that Captain Cook gave her to the royal family of Tonga way back in 1777, making her nearly as old as the good old USA. Some dispute this story, although there is no doubt that she lived in Tonga for a very long time indeed. No stranger to royalty, she greeted the newly crowned Queen Elizabeth II when that monarch visited Tonga, a British protectorate, in 1953.

That's Elizabeth on the left, Tu'i Malila on the ground. You knew that, right?

As we bid farewell to this extraordinary reptile, we greet a new British import at the top of the American popular music charts. Herman's Hermits, hailing from Manchester, England, hit Number One this month with their version of Mrs. Brown, You've Got a Lovely Daughter, a song first performed by actor Tom Courtenay in a British television play a couple of years ago.

Unlike many of the singers in British rock 'n' roll bands, lead man Peter Noone makes no attempt to disguise his accent. If anything, it sounds like he's exaggerating his Mancunian way of talking. (Yes, I just now learned the word Mancunian, and I'm showing off.)

Nobody in the band is named Herman. Go figure.

Exit Cele, Enter Joseph

My esteemed colleague John Boston has already reported, in fine detail, on the Ziff-Davis company selling Amazing and Fantastic to Sol Cohen. Editor Cele Goldsmith Lalli will remain with Ziff-Davis, working on their publication Modern Bride. Frankly, I think that's a step up for her, given the minimal interest that the publisher had in their fiction magazines.

Joseph Wrzos, using the more Anglo-Saxon name Joseph Ross, will be the editor, under the direction of Cohen. Fantastic will contain reprints from old issues of the two Ziff-Davis magazines, as will Amazing. The sister publications will alternate bimonthly publication. Of course, they will continue to publish new stories purchased by Lalli for a while, given the exceedingly slow way the publishing industry works. I hope that Wrzos will also offer previously unseen work once these run out.

As we lift a glass of champagne to Cele, and bid her a fond bon voyage as she sets sail for the world of wedding dresses and honeymoons, let's take a look at the last issue that will bear her name.

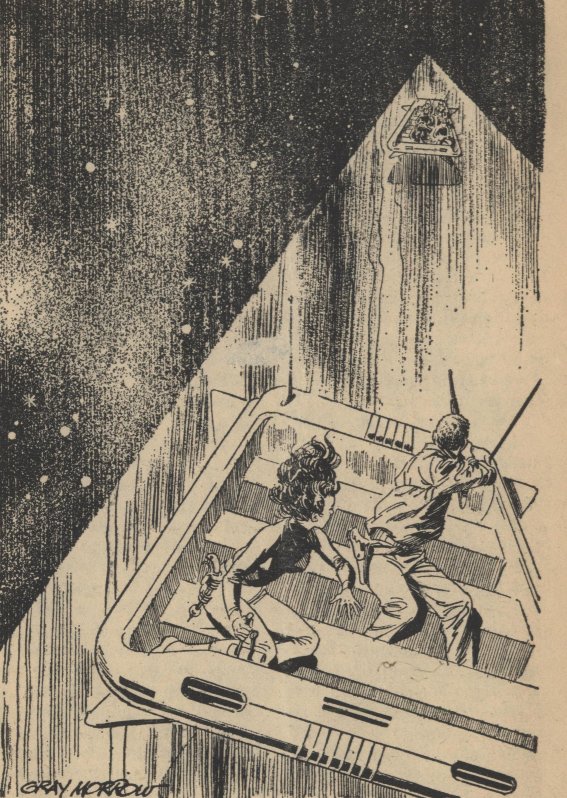

Cover art by Gray Morrow

Thelinde's Song, by Roger Zelazny

You may recall the story Passage to Dilfar in the February issue, which introduced the character Dilvish the Damned. He was a mysterious figure indeed, and that tale provided only hints as to his strange nature. This one gives us some of his background.

A young sorceress sings a ballad about Dilvish and the evil wizard Jelerak. Her mother warns her not to speak the name of the villain aloud, lest she draw the attention of one of his wicked minions. She then relates the encounter between the half-elf Dilvish and the sorcerer, as Jelerak was about to sacrifice a virgin in order to work his black magic.

Jelerak turned the heroic Dilvish into stone, and sent his soul to Hell. A couple of centuries later, Dilvish managed to return to life, this time with a talking steel horse as his mount. The rest of the story shows us why it's a bad idea to speak the name of Jelerak.

Although Dilvish only appears in flashback, he dominates the story, becoming a fascinating character. The author's style is poetic, creating a memorable sword-and-sorcery adventure. I hope we see more tales in this series.

Four stars.

This anonymous illustration appears at the end of the story. It has nothing to do with anything in the magazine.

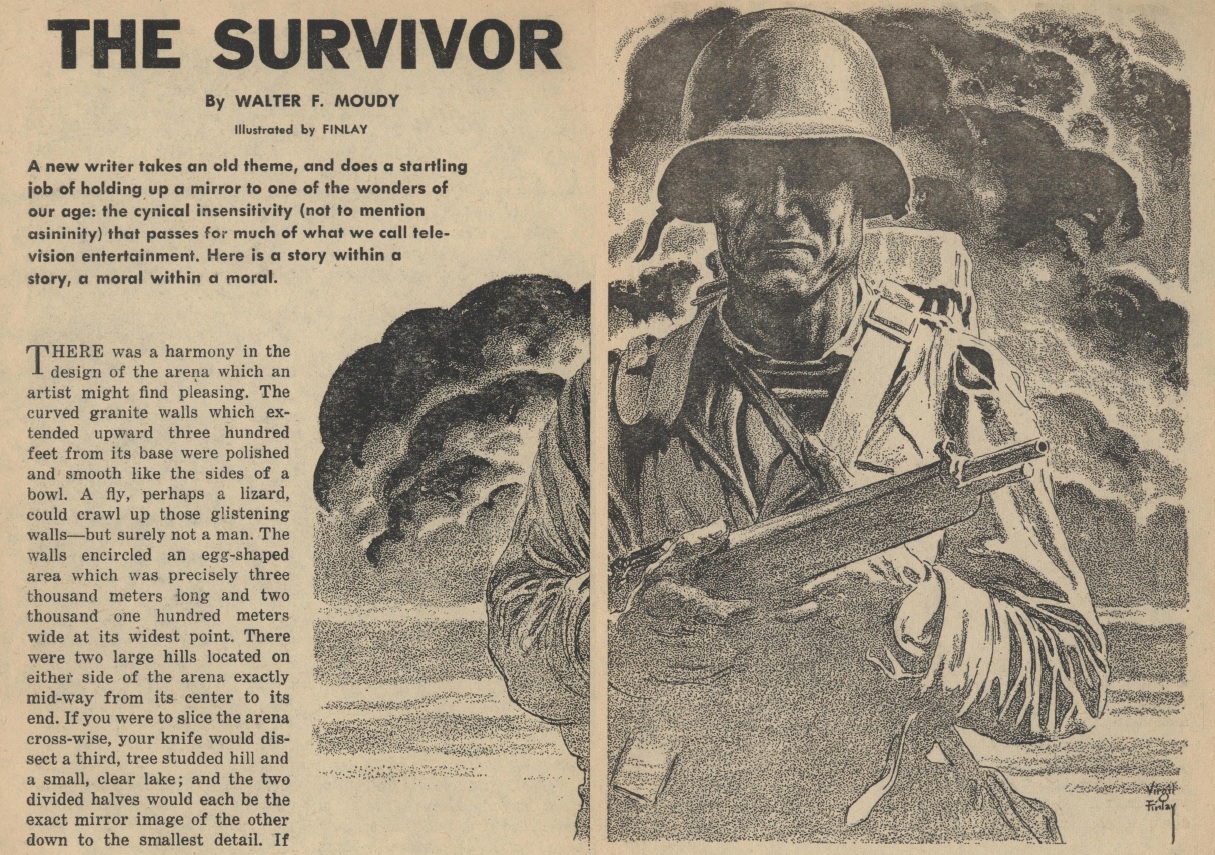

The Destroyer, by Thomas N. Scortia

The setting is some time after a limited nuclear war, which apparently more-or-less destroyed Asia. The Western world, it seems, recovered nicely, leading to a society well on its way to a technological utopia. People travel by riding some kind of electromagnetic beams. For all intents and purposes, this is pretty much flying like Superman.

Anyway, the protagonist is the head of something called the Genetic Bank, which controls the manipulation of plant and animal genes. A government agent asks him to report any evidence of human genetic tampering, which is a crime so severe that it carries the only death penalty left on the book.

The hero investigates the case of a young boy named Julio. Although classified as severely mentally disabled, he has somehow managed to create a pair of magnetic blocks that produce a stream of energy between them.

Meanwhile, the main character's love interest, a woman just back from Titan, is dying from a fungus acquired on that moon of Saturn. When Julio removes a mole from the man's hand, just by thinking about it, you can predict what's going to happen at the end. Along the way the government agent gets involved in things, seeing Julio as a threat to the planet.

There are very few surprises in this tale of a kid with superhuman mental powers. The background is somewhat interesting, even if implausible. The premise that Earth folk have become timid and complacent, compared to those who explore the Solar System, was intriguing, but didn't lead to much. The notion that there is something inherently wrong with the accepted view of science, compared to the way the boy thinks, was unconvincing. Overall, I got the feeling that I've read this stuff before, as if it were a mediocre story from Analog.

Two stars.

The Penultimate Shore, by Stanley E. Aspittle, Jr.

A writer completely unknown to me spins a dream-like fantasy with hints of allegory. A man named Cipher winds up on a deserted shore after a shipwreck. Half-sunken into the ocean are the ruins of a city. He has visions of a boy and girl in the waves. A woman named Huitzlin, the Aztec word for hummingbird, emerges from the sea and becomes his lover. An old man called Thanatos shows up as well. It all leads up to Cipher's final fate.

I really don't know what to make of this story. It's full of beautiful and evocative descriptions, but the author's intention is opaque. The character's names are suggestive, but the symbolism is unclear, except for the way that Thanatos is explicitly connected with death. If nothing else, it made me think, which is a good thing, I suppose.

Three stars.

The Other Side of Time (Part Three of Three), by Keith Laumer

Our universe-hopping narrator escapes from the prehistoric world where he wound up last time with the help of his ape-man buddy from another reality. The hairy fellow explains that the evil folks from yet another parallel cosmos — another type of ape-men — destroyed the hero's home world.

All seems lost, until the buddy suggests that it might be possible to travel to that universe in such a way that the narrator arrives there before it's wiped out. In a nutshell, time travel.

The hero shows up just a short time before things are going to go very badly indeed. Not only does he face the menace of the invading ape-men, he has to convince the local authorities of his identity. Then there's the mysterious burning figure he encountered in the first installment; what does that have to do with anything?

After the relatively calm mood of the second part, the conclusion of the novel returns to the frenzied pace of the first part. There's also a lot of scientific double talk to try to justify the odd way that time travel operates in this story. It held my interest, even if I didn't believe in anything that was happening for a moment. Compared to the highly enjoyable middle section, the rest of the novel is merely a decent enough science fiction action yarn.

Three stars.

Another piece of filler art. I actually like this abstract image.

The Little Doors, by David R. Bunch

Two pages of pure surrealism from the the magazine's most controversial author. Some white egg-shaped things come out of the little doors of the title and onto an egg-shaped stage. Rectangular black things show up, open the lids of the egg-things, put pieces of themselves inside, and pull out small stones of multiple colors.

If the author is trying to make some kind of serious point, he doesn't help matters by called the stage ogg, the white things loolbools, and the black things guenchgrops. Maybe it's just my dirty mind, but I got the feeling that this was some kind of bizarre metaphor for human reproduction. I have to give it a little credit for sheer weirdness.

Two stars.

Has someone been doodling on the page?

Phog, by Piers Anthony

The inhabitants of a strange world face the menace of a seemingly sentient cloud of poisonous gas, as well as the deadly beast that lurks inside it. After losing his sister to the thing, a boy grows up to build an elaborate trap for it. Capturing and destroying the cloud and the creature is not at all easy, coming only at great cost.

The author certainly shows plenty of imagination. The way in which the young man uses sunlight, the cloud's only weakness, is interesting. Other than that, the plot proceeds just about the way you expect it to.

Three stars.

Silence, by J. Hunter Holly

Because the Noble Editor wishes to keep track of the number of female authors published in the genre magazines, allow me to point out the J stands for Joan. She's published half a dozen or so science fiction novels. I believe this is her first short story to see the light of day.

In an overpopulated future full of noisy gadgets, the level of sound increases to the point where people no longer hear. Their ears still work, you understand; it's just that their brains turn off the sensation of hearing. Music is just something that causes needles to move around on dials.

The protagonist is one such musician. He regains his hearing, in a society that has completely forgotten about sound, by blocking out all sources of noise, until his brain regains its lost function. His attempt to bring his rediscovery of real music to audiences leads to an ironic ending.

The premise is intriguing, if not the most believable one in the world. I found it hard to accept that music would survive in the way the story suggests among people who can't hear it. I'll admit that I liked the downbeat conclusion.

Three stars.

Before We Say Farewell

We have a typical issue of the magazine, with some high points, some low points, and a lot in the middle. I'd like to take a moment to look back on the editor's time with the publication. She introduced promising new writers like LeGuin, Disch, and Zelazny, who have already proved their worth. More questionably, she published the unique work of Bunch, which certainly tests the limits of fantastic literature. She also helped Leiber get back to the typewriter, which justifies her career all by itself. I'm sure we all wish her well in her new line of work.

Thanks, Cele!

![[May 22, 1965] Goodbye and Hello (June 1965 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Fantastic_v14n06_1965-06_0000-2-672x265.jpg)

![[May 14, 1965] Keep A Civil Tongue In Your Head (July 1965 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v03n02_1965-07_0000-2-672x318.jpg)

![[May 12, 1965] Da Capo (June 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/amz-0665-cover-391x372.png)

![[May 8, 1965] Skip to the end (June 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/650508cover-535x372.jpg)

![[April 24, 1965] Every Silver Lining Has A Cloud (May 1965 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Fantastic_v14n05_1965-05_0000-2-672x340.jpg)

![[April 12, 1965] Not Long Before the End (May 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/650412cover-672x372.jpg)

![[April 2, 1965] SPEAKING A COMMON LANGUAGE (May 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/IF-April-cover-647x372.jpg)

![[March 26, 1965] Digging Up the Past (April 1965 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Fantastic_v14n04_1965-04_0000-2-672x372.jpg)

![[March 16, 1965] Browsing the Stacks (May 1965 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v03n01_1965-05_0000-2-672x316.jpg)

![[March 8, 1965] An Alien Perspective (April 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/650308cover-435x372.jpg)