by Gideon Marcus

In all the old familiar places…

All summer long, the Traveler family's television tradition has included the game show, Password. Though it may seem odd that such a program should rival in importance to us such stand-outs as Secret Agent and Burke's Law, if you read my recent round-up of the excellent TV of the 64-65 season, you'll understand why we like the show.

Sadly, the September 9 episode marked the beginning of a hiatus and, perhaps, an outright cancellation of the show. No more primetime Password, nor the daily afternoon editions either. Whither host extraordinaire Allen Ludden?

Apparently, What's my Line! Both Ludden and his wife, Betty White, were the mystery guests last week; I guess they had the free time. They were absolutely charming together, and it's clear they are still very much in love two years into their marriage.

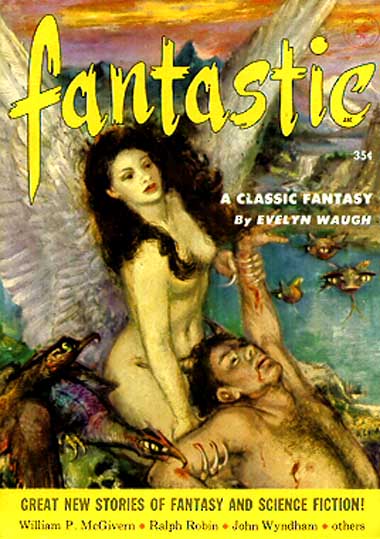

Speaking of anniversaries, Galaxy, one of the genre's most esteemed monthly digests, is celebrating its 15th. To mark the occasion, editor Fred Pohl has assembled a table of contents contributed by some of the magazine's biggest names (though I note with sadness that neither Evelyn Smith nor Katherine MacLean are represented among them). These "all-star" issues (as Fantasy and Science Fiction calls them) often fail to impress as much as ones larded with newer writers, but one never knows until one reads, does one?

So, without further ado, let's get stuck in and see how Galaxy is doing, fifteen years on:

The issue at hand

by John Pederson, Jr.

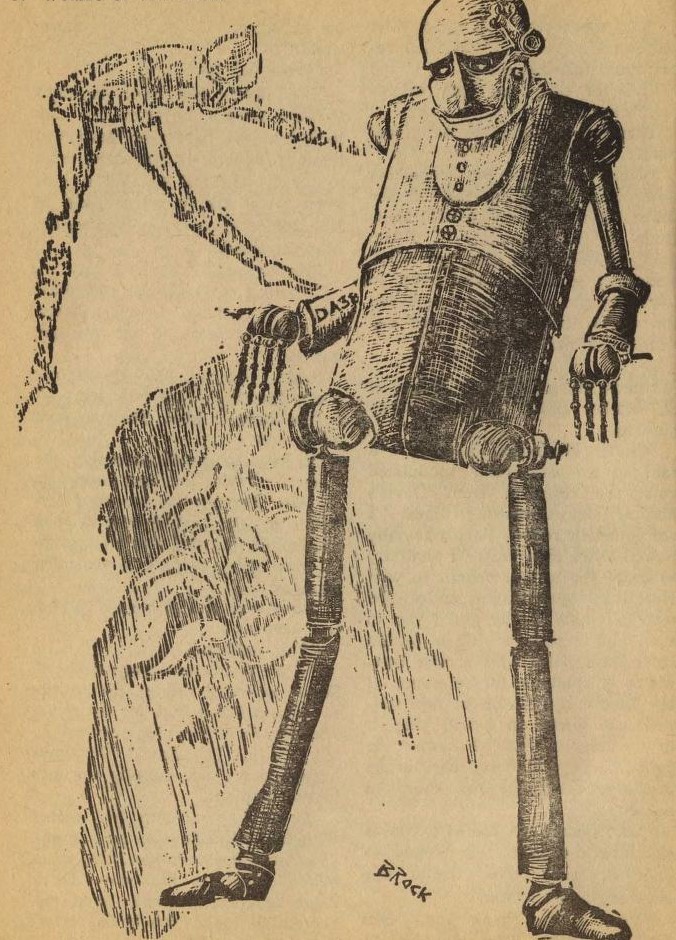

The Age of the Pussyfoot (Part 1 of 3), by Frederik Pohl

The editor of Galaxy has a penchant for providing a great deal of his own material to his magazines. Normally, I'd be worried about this. It could be a sign of an editor taking advantage of position to guarantee sale of work that might not cut the mustard. And even if the work is worthy, there is the real danger of overcommitment when one takes on the double role of boss and employee.

That said, some editors just find creation too fun to give up (yours truly included) and in the case of Pohl, he usually turns in a good tale, as he has for decades, so I won't begrudge him the practice.

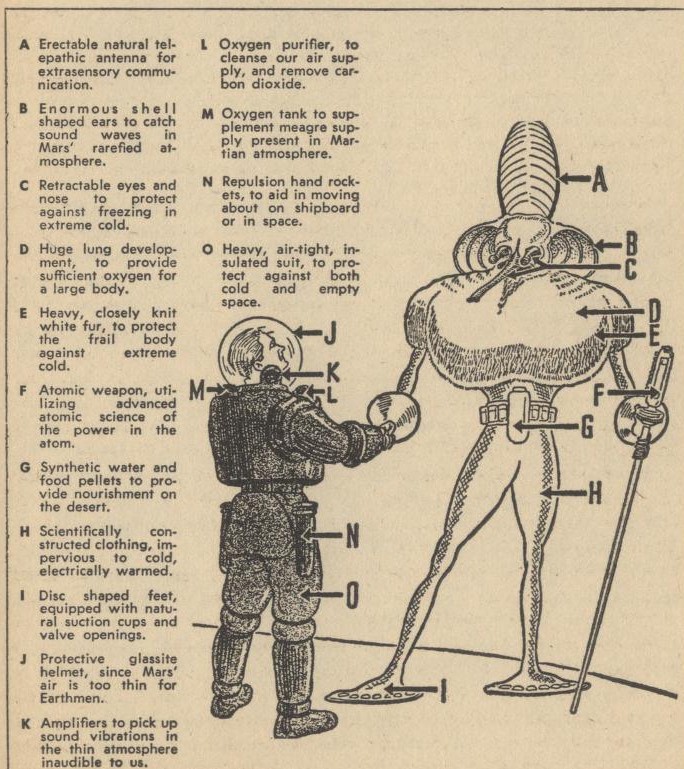

Indeed, Pussyfoot is a welcome addition to the mag. A variation on the classic The Sleeper Awakes theme, in this case, the time traveling is done via the rather new technology of cryogenics. Indeed, protagonist Charles Forester, 37-year old erstwhile fireman, is one of the very first corpses to be frozen circa 1969, and wakes up in the overcrowded but utopian world of 2527 A.D.

by Wallace Wood

Feeling immortal (with some justification – no one really dies anymore; they just get put on ice until they can be brought back, often within minutes) and also wealthy (but $250,000 doesn't stretch as far as it used to) Forester takes a while to really come to grips with his new situation, always just a touch too clueless for his own good, and perhaps plausibility.

Very quickly, he learns that things are not perfect in the future: being immortal means one can be murdered on a lark and the culprits go unpunished. Inflation has rendered Forester's fortune valueless. He must get a job, any job. But the one he finds that will employ an unskilled applicant turns out to be the one no one wants: personal assistant to a disgusting alien!

There's some really good worldbuilding stuff in this story, particularly the little rod-shaped "joymakers" everyone carries that are telephone, computer terminal, personal assistant, drug dispenser, and more. I also liked the inclusion of inflation, which is usually neglected in stories of the future. It all reads a bit like a Sheckley story writ long, something Sheckley's always had trouble with. It's not perfect, but it is fun and just serious enough to avoid being farce.

Four stars for now,

Inside Man, by H. L. Gold

The first editor of Galaxy started out as a writer, but even though he turned over the helm of his magazine four years ago (officially – it was probably earlier), he hasn't published in a long time, so it's exciting to see his byline again. Inside Man is a nice, if nor particularly momentous, story about a fellow with a telepathy for machines. And since machines are usually in some state of disrepair, it's not a very pleasant gift.

Three stars.

The Machines, Beyond Shylock, by Ray Bradbury

Judith Merril sums up Bradbury beautifully in this month's F&SF, describing him as the avatar of science fiction to the lay population, but deemed a mixed bag by the genre community. His short poem, about how the human spirit will always have something robots do not, is typically oversentimental and not a little opaque. And it's not just the font Pohl used.

Two stars.

Fifteen Years of Galaxy — Thirteen Years of F.Y.I., by Willy Ley

The science columns of Willy Ley comprised one of main draws for Galaxy back when I first got my subscription. In this article, Ley goes over the various topics of moment he's covered over the last decade and a half, providing updates where appropriate. It's a neat little tour of his tenure with the magazine.

Four stars.

A Better Mousehole, by Edgar Pangborn

Pangborn, like Bradbury, is another of the genre's sentimentalists. When he does it well, he does it better than anyone. This weird story, told in hard-to-read first person, said protagonist being a bartender who finds alien, thought-controlling blue bugs in his shop, is a slog.

Two stars.

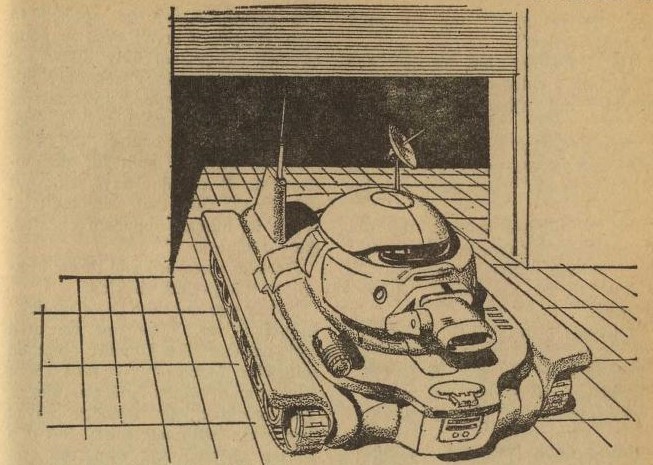

Three to a Given Star, by Cordwainer Smith

Oh frabjous day! A new Instrumentality story! This one tells the tale of three unique humans sent off to pacify the gabbling, cackling cannibals of Linschoten XV: "Folly", once a beautiful woman and now a 11-meter spaceship; "SAMM" a quarter-mile long bronze statue possessing a frightening armory; and "Finsternis", a giant cube as dark as night, and with the ability to extinguish suns.

by Gray Morrow

Guest appearances are made by Casher O' Neill and Lady Ceralta, two of humanity's most powerful telepaths whom we met in previous stories.

I've made no secret of my admiration for the Instrumentality stories, which together create a sweeping and beautiful epic of humanity's far future. Three has a bit of a perfunctory character, somehow, and thus misses being a classic.

Still, even feeble Smith earns three stars.

Small Deer, by Clifford D. Simak

In Deer, a fellow makes a time machine, goes back to see the death of the dinosaurs, and discovers that aliens were rounding them up for meat… and that they might come back again now that humanity has teemed over the Earth.

A throwback of a story and definitely not up to Simak's standard. A high two (or a low three if you're feeling generous and/or missed the last thirty years of science fiction).

The Good New Days, by Fritz Leiber

On an overcrowded Earth, steady work is a thing of the past. Folks get multiple part time gigs to fill the time, including frivolous occupations like smiling at people on the way to work. Satirical but overindulgent, I had trouble getting through it. Two stars.

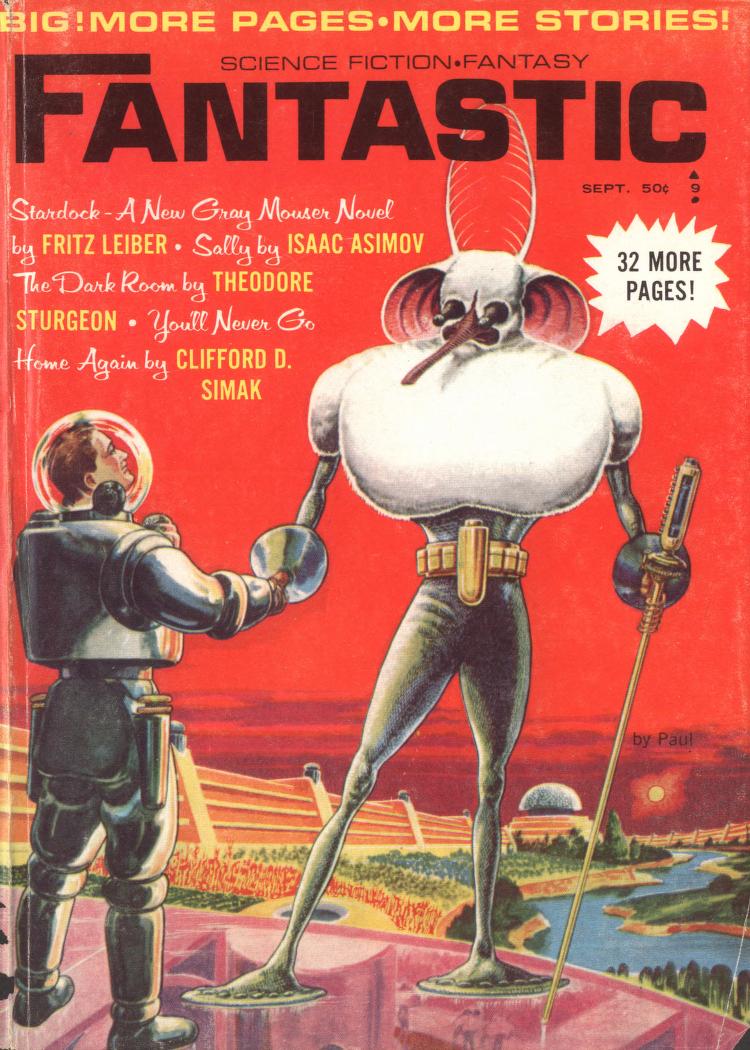

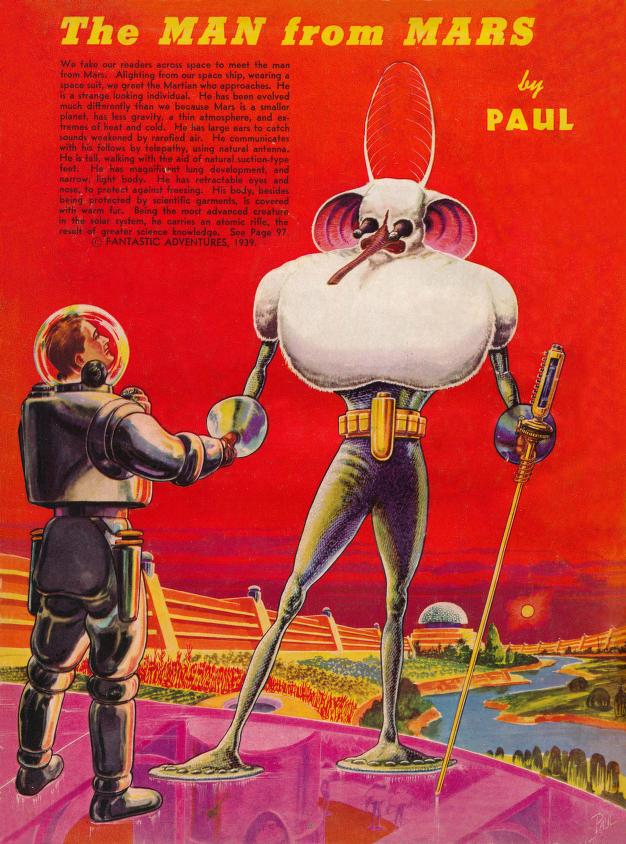

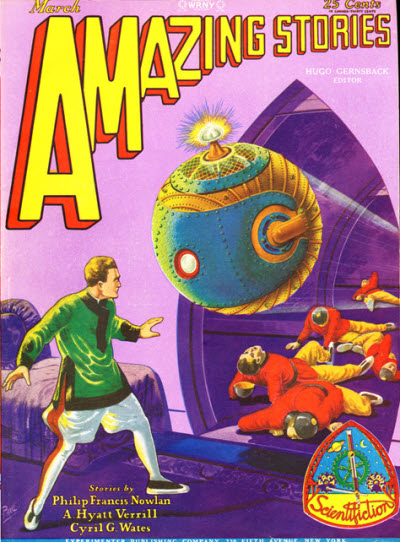

Founding Father, by Isaac Asimov

Dr. A was lured back into the world of fiction after an eight-year almost complete hiatus; apparently he can be cajoled into almost anything. In Father, based on this month's cover, five marooned space travelers try to cleanse a planet of its poisonous ammonia content before their dwindling oxygen supplies run out.

It's a fair story, but I had real issues with the blitheness with which the astronauts plan to destroy an entire ecosystem that requires ammonia to survive. In the end, when terrestrial plants manage to take root on the planet, spelling doom for the native life, it's heralded as a victory.

Two stars.

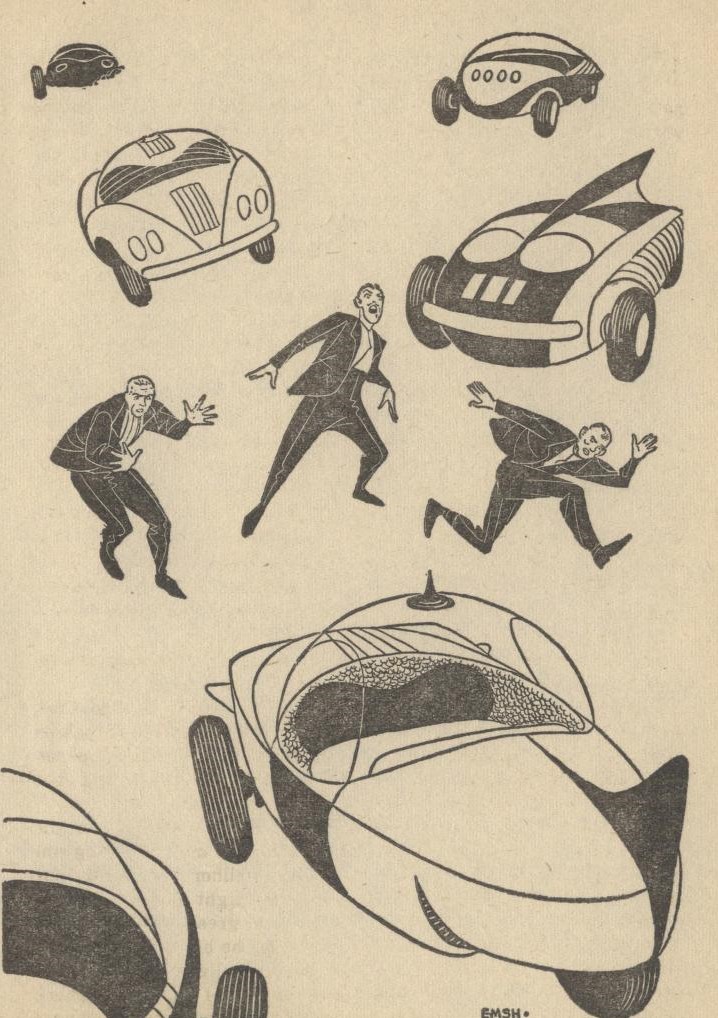

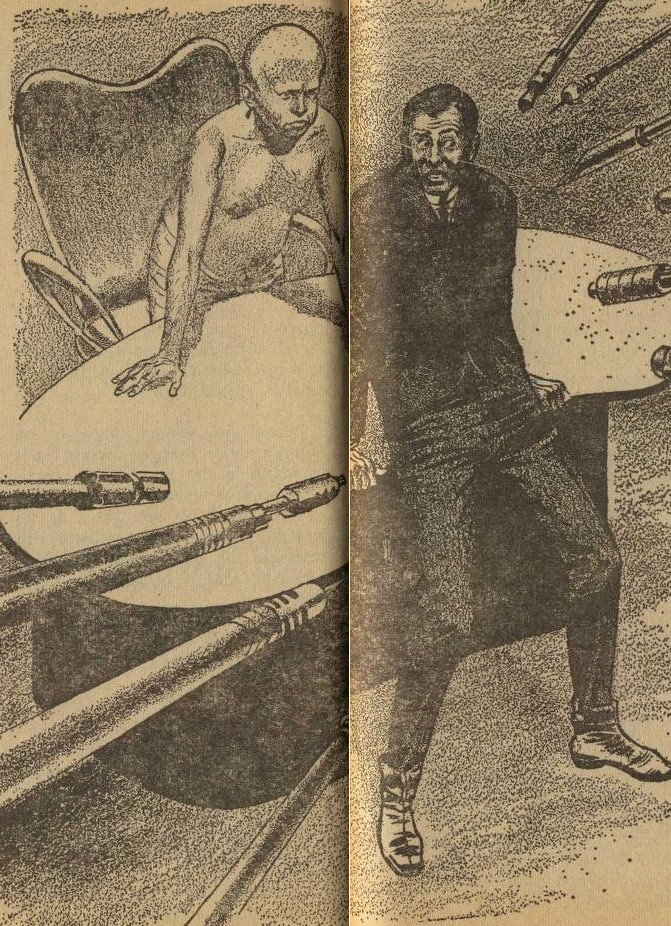

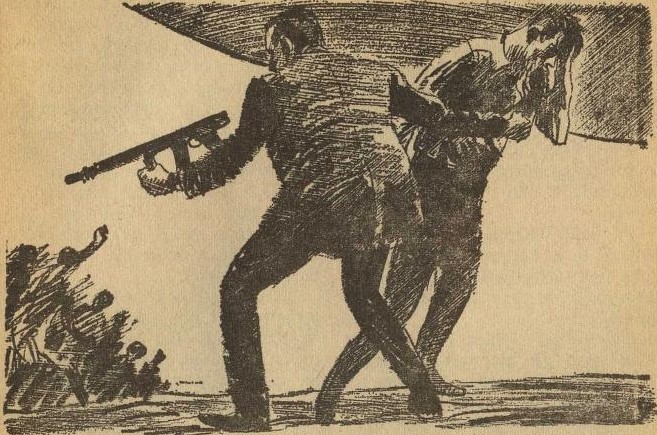

Shall We Have a Little Talk?, by Robert Sheckley

by Jack Gaughan

Bob Sheckley was a Galaxy staple (under his own name and several pseudonyms) for most of the 1950s. His short stories are posssibly the best of anyone's, but he eschewed them for novels that just didn't have the same brilliance.

Well, he's back, and his first short story in Galaxy in ages is simply marvelous. It involves a representative of a rapacious Terra who travels to a distant world to establish relations, said contact a prelude to its ultimate subjugation. But first, he has to establish meaningful communications.

Fiercely satirical and hysterical to boot, Talk is Sheckley in full form.

Mun, er, five stars.

Summing up

In the end, this all-star issue was, as usual, something of a mixed bag. Still, there's enough gold here to show that the river Gold established is still well worth panning. Here's to another fifteen years!

[Journey Press now has three excellent titles for your reading pleasure! Why not pick up a copy or three? Not only will you enjoy them all — you'll be helping out the Journey!]

![[September 14, 1965] The Face is Familiar (October 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/650914cover-551x372.jpg)

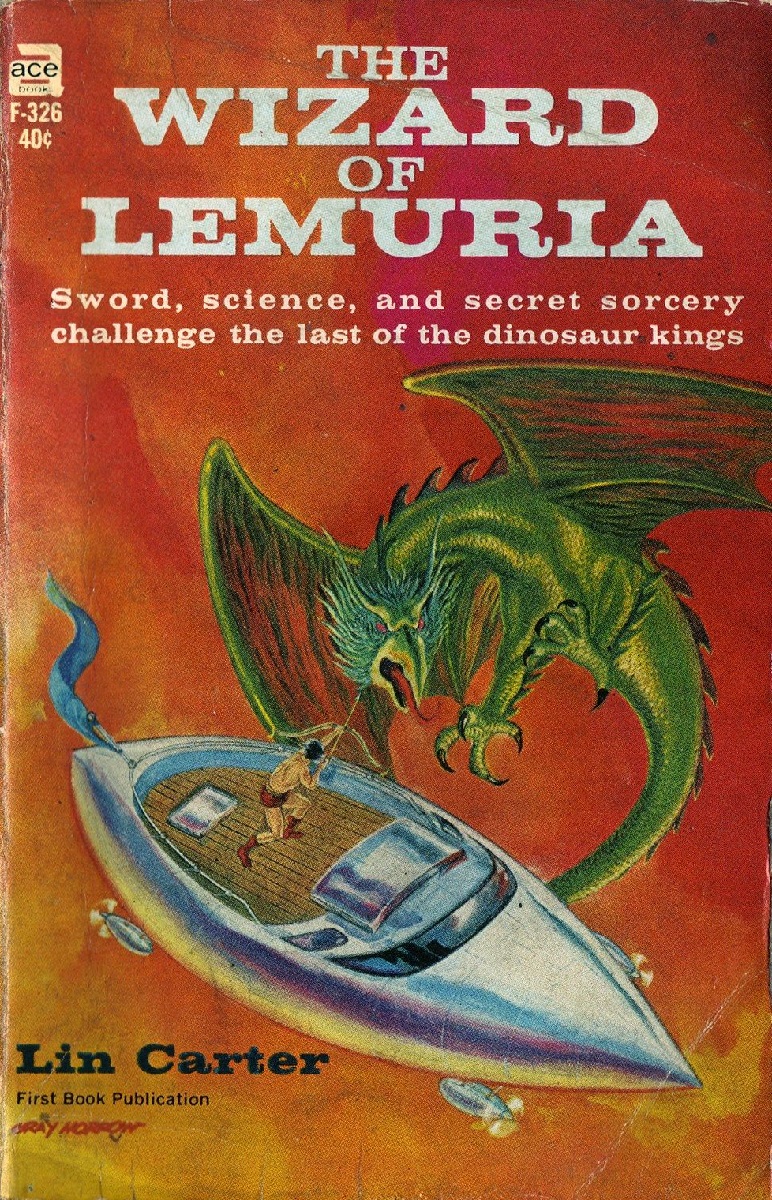

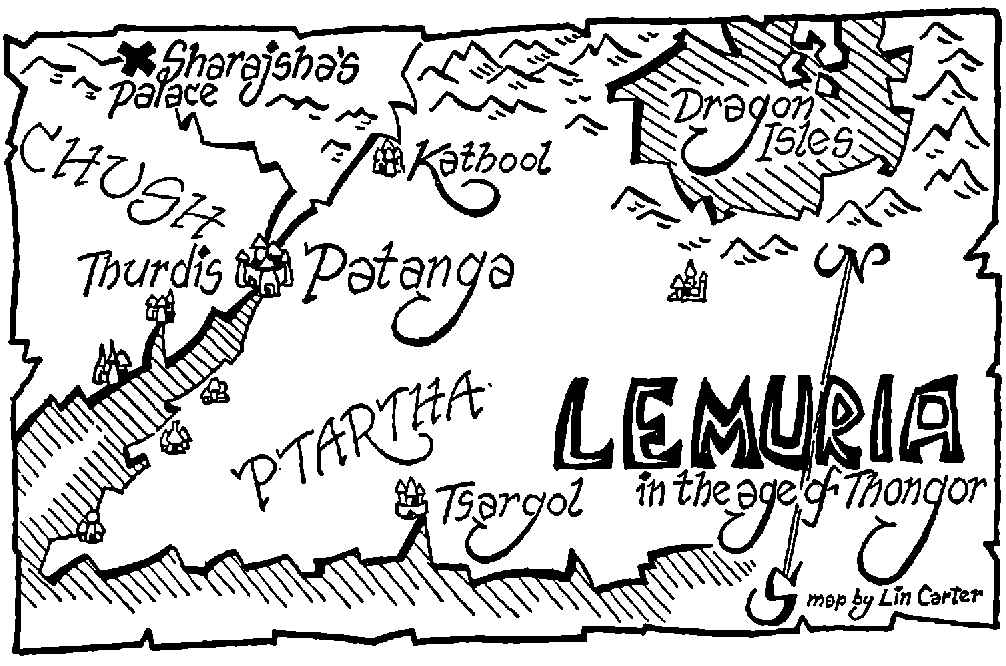

![[September 10, 1965] So Many Thews (Lin Carter's <em>The Wizard of Lemuria</em>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Cover-Wizard-of-Lemuria-672x372.jpg)

width="150"/>

width="150"/>

![[September 6, 1965] War and Peace (October 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/IF-1965-10-cover-657x372.jpg)

![[August 10, 1965] Binary Arithmetic (September 1965 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Fantastic_v15n01_1965-09_0000-2-672x372.jpg)

![[August 2, 1965] Expansion and Contraction (September 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/IF-1965-09-Cover-654x372.jpg)

![[July 18, 1965] The Prodigal Returneth (September 1965 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v03n03_1965-09_0000-2-672x293.jpg)

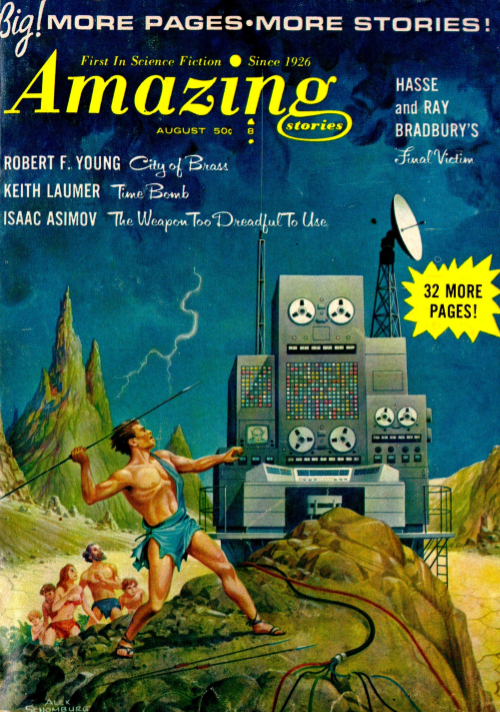

![[July 14, 1965] The New Dispensation (August 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/amz0865-cover-500x372.png)

![[July 8, 1965] Saving the worst for first (August 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/650708cover-521x372.jpg)

![[July 2, 1965] Gallimaufry (August 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/IF-cover-1965-08-649x372.jpg)

![[June 2, 1965] Heck in a Handbasket (July 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/1965-07-IF-cover-653x372.jpg)