By Jason Sacks

Well, so far this has been a great month. Last week saw the end of a dynamite World Series, in which Sandy Koufax, the greatest pitcher of his generation, showed himself to be one of the greatest Jews of his generation as well. It was tremendously meaningful to my family that Sandy refused to start Game 1 for the Dodgers against the Minnesota Twins since the day coincided with our holy day of Yom Kippur.

As Sandy said, "I've taken Yom Kippur off every year for the last 10 years. It was just something I've always done out of respect."

As if that wasn't good enough, Koufax dominated games 5 and 7 of the series, with his electric fastball mowing down batters in a pair of crucial shutout victories. The Twins played well, and were outstanding American League champs – Tony Oliva is a monster – but it seems the Koufax gave the Dodgers the edge, and turned the '65 Series into a classic.

At the movie theatre, my wife and I caught The Bedford Incident last week at our favorite theatre here in north Seattle. If you haven't had a chance to see it yet, the film is well worth a night out — if, that is, you can handle an intense and sometimes bleak drama.

Richard Widmark turns in a powerful performance as a zealous battleship captain on the search for an elusive Soviet nuclear submarine. Also featuring Sidney Poitier and Martin Balsam, this black and white drama treads similar ground to last year's thrilling Fail Safe and ends in a similarly dramatic way.

The Hunter Out of Time, by Gardner F. Fox

If it seems like I'm dragging my feet a bit before talking about my entry for this month's Galactoscope, well, you're right. Gardner Fox's new novel is the epitome of mediocrity, a book that will give you 40¢ worth of excitement but not a whole lot more. The fantastic Mr. Fox is a prolific author who churns out more books and comic book stories than nearly anyone else living. Sometimes that causes him to create some delightful work. Other times it seems like he is just delivering words just to deliver him a paycheck. There's nothing necessarily wrong with that – I'm sure the man has a mortgage to pay – but it also represents a lost opportunity.

See, this book starts out with one of the most striking first lines I can remember.

I saw myself dying on the other side of the street.

The first page builds on that momentum, with the protagonist describing his body as "blood oozed over my fingers where I held that awesome wound."

I mean, seriously, how can you read a first page like that without feeling like you have to read more? Mr. Fox is an old pro and he clearly knows some classic tricks. As I read that book, I leaned back, took a deep breath, and readied myself for a page-turning thrill ride.

Cover by Gray Morrow

But, dear reader, I'm sorry to inform you that all the best writing in The Hunter Out of Time happens on the first couple of pages. It soon turns out that the man who falls to Earth is a time traveler from the far, far future who traveled back through a supposedly impregnable barrier to steal the man's identity. The time traveler is named Chan Dahl and soon other time-displaced men come to our time, confuse our guy, Kevin Cord for Dahl, and that unleashes the most obvious and cliched adventure you can imagine.

There's little in The Hunter Out of Time you haven't seen before. Fox gives us fantastic devices, headspinning time travel with seemingly arbitrary rules, and the obligatory beautiful, weak babe from the future. Of course Cord uses his native 20th century skills to overcome his opposition, of course Cord and the woman fall in love, and of course Fox leaves room for a sequel if somehow people want to read more of this frightfully ordinary pap.

I could go on and on about this book, but hey, it costs 40¢, it'll take you a couple hours to read, and it's got a pretty nice cover by artist Gray Morrow. I'd rather spend my time watching young Warren Beatty in Mickey One in the theatres, but you won't hate this book and it's pleasing enough entertainment for a rainy Seattle Sunday.

2 stars.

Solid Fuel

by John Boston

The rising star John Brunner has produced ambitious work such as The Whole Man and the upcoming The Squares of the City, both from Ballantine in the US, and a raft (or flotilla) of unpretentious upscale-pulp adventures for Ace Books. Some of the best of the latter were mined from the UK magazines edited by John Carnell.

by Jacks

But there’s a lot more. Brunner has been one of the mainstays of the UK magazines for a decade, but much of his best magazine work has not been reprinted because it’s too short for separate book publication and too long to fit in the usual anthologies or collections. The UK publisher Mayflower-Dell, previously distinguished by its unsuccessful attempt to bring Fanny Hill: Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure to the British public, remedies a bit of this omission with Now Then, a collection of three novellas, two from the Carnell magazines and the other, his first professional sale, from Astounding in 1953.

The book opens with the energetically clever and creepy Some Lapse of Time, from Science Fantasy #57 (February 1963). Dr. Max Harrow is having a bad dream of a group of starving people living in ruins, one of whom is holding a human finger bone in his hand. He wakes and there is someone at his door: the police, because a tramp has collapsed in his garage. The tramp proves to be suffering a rare disease (heterochylia, an inability to metabolize fats, which become lethal) that Harrow is uniquely qualified to recognize, his infant son having died of it only recently, and which should have made it impossible for the tramp to survive to adulthood. The tramp also has clamped in his hand a human finger bone—the same bone, the end of the left middle finger, as in Harrow’s dream.

Unintelligible to the hospital staff, the tramp proves when examined by a philologist to speak a badly distorted version of English, like one might expect a primitive and isolated group to use. Meanwhile, Harrow’s marriage is blowing up under the emotional stress caused by his son’s death and his own preoccupation. When his wife slams the car door in his face, she catches his hand in the door and severs the end of his left middle finger, which falls down a gutter. Meanwhile, the tramp is sent for a head x-ray, but he turns out to be so radioactive that not only do the films turn out unusable but he has to be put in strict isolation.

Brunner brings all these elements to a thoroughly grotesque resolution—it doesn’t entirely work, but is a grimly ingenious nice try. Others apparently think so too; it is rumored that a dramatization will be broadcast later this year in the BBC’s Out of the Unknown TV series. Four stars.

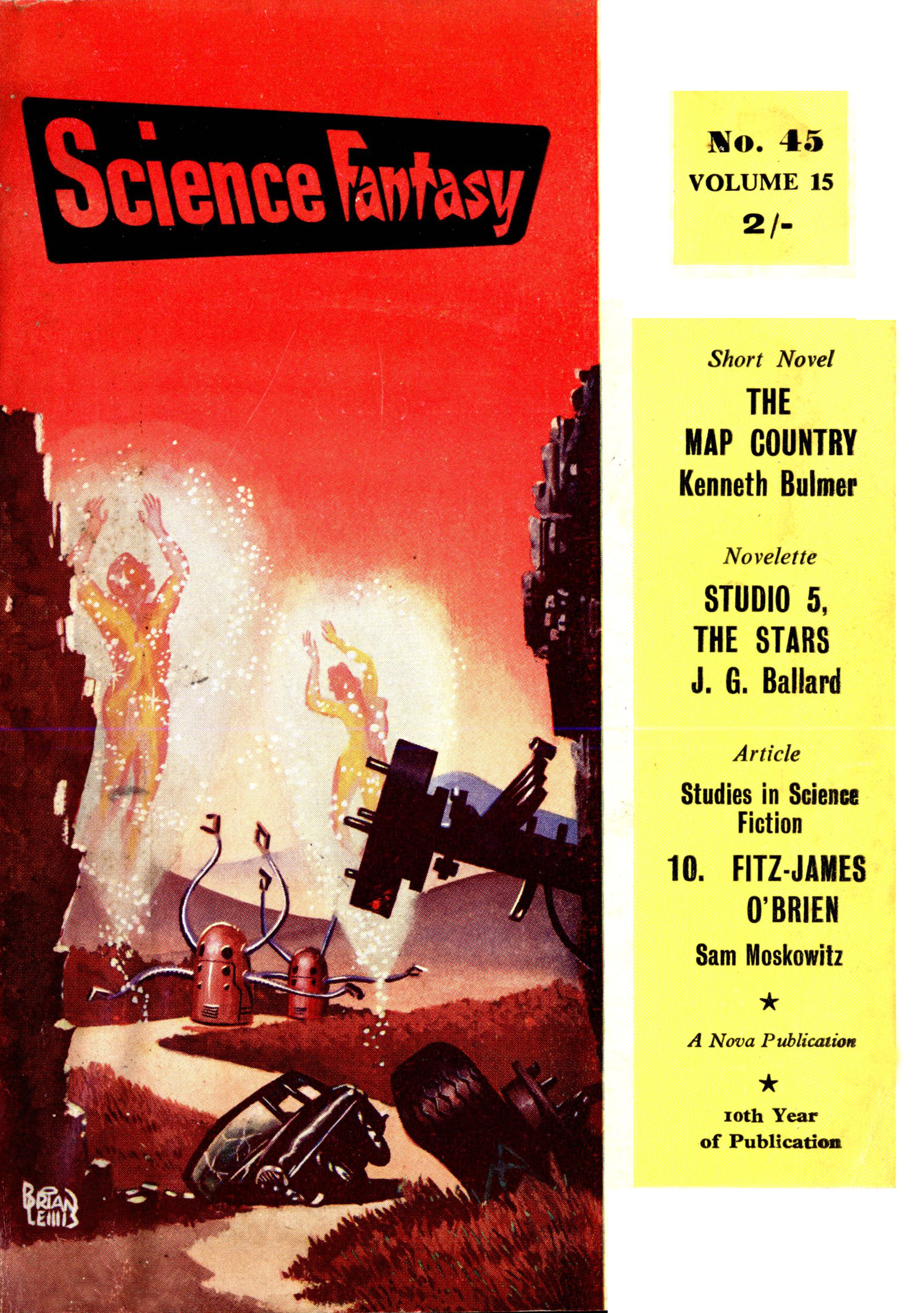

Next up is Imprint of Chaos, also from Science Fantasy (#42, August 1960), one of a number of outright fantasies Brunner contributed to that underrated magazine. This one introduces us to a character mainly called “the traveler,” who we are repeatedly told has “many names but one nature,” unlike the rest of us who I suppose contain multitudes.

The traveler has been appointed (by whom, or Whom, or What is not explained) as a sort of metaphysical supervisor over part of the universe, charged with ensuring the primacy of order over chaos. He is on his way to Ryovora, a formerly sensible town where they have now decided they need a god.

So the traveler nips out to our Earth and snatches the unsuspecting Bernard Brown from a hike in the wood, tells him he’s unlikely to find his way home, but gives him directions to Ryovora. There, to his discomfiture, Brown is welcomed as a god, and when the next city over hears about it and sends over their god, Brown sends it packing in terror. Then the Ryovorans say they could have done it themselves (though they didn’t), and excuse Mr. Brown, after a final scene where he and the traveler bruit the futility and undesirability of magic.

A fantasy writer bad-mouthing magic may seem incongruous, but this rationalist in spite of himself really hates it, and comes not to praise magic but to bury it, though only after enough colorful magical episodes to entertain the rubes. Here the tension is more extreme than usual. His earlier fantasies mostly featured incursions of magic into the world of ordinary salt-of-the-earth types. Here, the entire setting is exotically magical, and the story is told in the fey and pompous cadences of high fantasy.

For example, from a conclave of the necromantic elite of Ryovora: “The Margrave nodded and made a comforting gesture in the air. He said, ‘But this cannot be the whole story. I move that we—here, now, in full council—ask Him Who Must Know.’” Brunner walks the edge of parody at times (“Tyllwin [a particularly powerful magician] chuckled, a scratching noise, and the flowers on the whole of one tree turned to fruit and rotted where they hung.”). But the story is clever and entertaining and merits its three stars, towards the high end.

Thou Good and Faithful is older; as mentioned, it is the first story Brunner sold to an SF magazine—and it was featured on the cover of the top-of-the-market Astounding (March 1953 issue). Moreover, the readers voted it best in the issue, and it was quickly picked up by Andre Norton for her pretty respectable YA anthology Space Pioneers. Not a bad start for an 18-year-old! Though Brunner has had some second thoughts about showing us his juvenilia; the acknowledgements note it appeared in the magazine “in a somewhat different form.” I haven’t compared the two texts, though there’s clearly some updating; in this version Brunner refers to something as “maser-tight,” and masers were barely invented when this story was first published.

The story is for most of its length a bog-standard though well-turned rendition of a basic plot: find a planet, there’s a mystery, what’s going on, are we scared? The mystery is an idyllic Earth-type planet inhabited only by robots, who presumably didn’t make themselves; what happened to the makers? The final revelation is partly in the direction of, say, Clarke’s Childhood’s End, and partly in the one suggested by the story’s title, so in the end it’s much more high-minded than the puzzle story it starts out as. This is all older news nowadays than it was in 1953, but it too merits a high three stars.

Summing Up

Now Then is a solid representation of the mid-length work of this very readable and thoughtful writer, and there’s enough in the Carnell back files for several more worthwhile volumes of Brunner novellas.

Two by Two

by Gideon Marcus

The Journey has made a commitment to review every piece of science fiction released in a year (or die trying). In pursuit of this goal, I've generally tried to finish every book I've started, and if unable to, I simply don't write about it.

It occurs to me, however, that the inability to finish a book is worth reporting on, too. And so, here are reports on two of this summer's lesser lights:

Arm of the Starfish, by Madeleine L'Engle

The latest from Madeline L'Engle, author of the sublime A Wrinkle in Time, starts promisingly. Adam Eddington is a freshman biology minor tapped to work with a Dr. O'Keefe on the Atlantic island of Gaia off the coast of Portugal. O'Keefe (a grown up Calvin, from Wrinkle) is working with starfish, zeroing in on an immortality treatment. Just prior to Adam's departure from Kennedy Airport, he runs across the beautiful young daughter of an industrialist, Kali, who warns Adam to stay away from the sinister-looking Canon Tallis, who is chaperoning the O'Keefes' precocious daughter, Poly.

Adam finds himself embroiled in international intrigue, not knowing who to trust. This is exciting at first, but a drag as things go on. Gone is the quietly lyrical prose of Wrinkle, replaced by a deliberately juvenile style leached of color. Events happen, one after another, but they are both difficult to keep track of and largely uninteresting. By the time Adam made it to Gaia, about halfway through the book, I found myself struggling to complete a page.

Life's too short. I gave up.

Quest Crosstime, by Andre Norton

Cover by Yukio Tashiro

Andre Norton has come out with the long-awaited sequel to her parallel universe adventure, The Crossroads of Time, starring Blake Walker. The universe Walker lives in is a bit like that of Laumer's Imperium series and Piper's Paratime stories: there's one Earth that has mastered the art of crossing timelines, and it has built an empire across these alternate Earths.

On Vroom, the imperial timetrack, there had been a devastating war that killed most of the female population, making them particularly precious. Also, mutation has made psionic ability the rule rather than the exception. The timeline is ruled by an oligarchy of 100 meritocrats.

At the start of Crosstime, Walker is dispatched to assist Marfy, whose twin sister, Marva, has been lost amongst the timeless — and all signs point to a kidnapping. Of course, the allure of all parallel universe books is the exploration of what-if, and so Walker and Marfy's trek spans a dead Earth where life never arose, a strange saurian Earth where sentient turtles and lizardmen rule, and ultimately, an interesting timeline in which Richard III won the battle of Bosworth Field while Cortez lost the battle of Tenochtitlan. By the Mid-20th Century, there is a Cold War between Britain and the Aztec Empire along a militarized Mississippi river. It is to this world that Marfy and her abductors are tracked, and it turns out that the kidnapping is part of a plot to topple Vroom's Ancien Regime.

True to form as of late, Norton sets up some genuinely interesting background, but the characters are as flat as the pages they appear on. This time, I made it through two thirds of the book, partly on momentum from the first book in the series, which I rather enjoyed. In the end, however, disinterest won out.

Call it two stars for both books.

Don't miss the next exciting musical guest episode of The Journey Show, October 24 at 1PM Pacific!

![[October 24, 1965] "What time is it?" (October Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/651024covers-1-672x372.jpg)

![[July 12, 1965] A pair of Aces (July 1965 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/650712covers-672x372.jpg)

![[June 26, 1965] Disappointing Duo (June Galactoscope #2)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/650626covers-672x372.jpg)

![[June 20, 1965] Ace Quadruple (June Galactoscope #1)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/650620cover-397x372.jpg)

The first story "What Rough Beast?" is the story of a young immigrant named Mike Kronski trying to make his way in America. However, Mike is not the simple East European immigrant he appears to be. He comes from far further afield, from an alternate universe. He also has the ability to bend reality to his will and has accidentally changed his world into ours.

The first story "What Rough Beast?" is the story of a young immigrant named Mike Kronski trying to make his way in America. However, Mike is not the simple East European immigrant he appears to be. He comes from far further afield, from an alternate universe. He also has the ability to bend reality to his will and has accidentally changed his world into ours. "Second Class Citizen" is the story of researcher Charles Craven and the subject of his studies, the dolphin Pete. Craven has taught Pete to understand and speak English, spell simple words and even do chemical experiments. While Craven patronisingly presents Pete to some visitors, we learn from background conversations that there is an international crisis going on. Craven is convinced that this crisis will blow over, like any other crisis before.

"Second Class Citizen" is the story of researcher Charles Craven and the subject of his studies, the dolphin Pete. Craven has taught Pete to understand and speak English, spell simple words and even do chemical experiments. While Craven patronisingly presents Pete to some visitors, we learn from background conversations that there is an international crisis going on. Craven is convinced that this crisis will blow over, like any other crisis before. The novella "Be My Guest" is the story of Kip Morgan, a young man who finds himself possessed by four bickering ghosts after a poisoning attempt gone wrong. Kip also has another problem, he as well as two women of his acquaintance have become invisible to everybody but each other.

The novella "Be My Guest" is the story of Kip Morgan, a young man who finds himself possessed by four bickering ghosts after a poisoning attempt gone wrong. Kip also has another problem, he as well as two women of his acquaintance have become invisible to everybody but each other. "God's Nose" is a short vignette that does exactly what it says on the tin. The unnamed narrator and his female friend debate what the nose of God would look like. Eventually, her lover Godfrey arrives. He has a very prominent nose.

"God's Nose" is a short vignette that does exactly what it says on the tin. The unnamed narrator and his female friend debate what the nose of God would look like. Eventually, her lover Godfrey arrives. He has a very prominent nose. The final story "Catch That Martian" feels very much like a mix between The Rithian Terror and "Be My Guest". Once again, we have a dangerous alien, the titular Martian, who can take on the appearance of any human being. And once again, we have people abruptly taken out of the real world and turned into "ghosts". A young police officer is determined to crack the mystery of the ghosts and catch the Martian in the act. He deduces that the ghosts must have annoyed the Martian somehow, mostly via making noise, and that the Martian has a taste for musical theatre. So the narrator traces the Martian to a Broadway theatre, determined to apprehend him. But before he can give chase, he falls into the orchestra pit, straight onto a bass drum.

The final story "Catch That Martian" feels very much like a mix between The Rithian Terror and "Be My Guest". Once again, we have a dangerous alien, the titular Martian, who can take on the appearance of any human being. And once again, we have people abruptly taken out of the real world and turned into "ghosts". A young police officer is determined to crack the mystery of the ghosts and catch the Martian in the act. He deduces that the ghosts must have annoyed the Martian somehow, mostly via making noise, and that the Martian has a taste for musical theatre. So the narrator traces the Martian to a Broadway theatre, determined to apprehend him. But before he can give chase, he falls into the orchestra pit, straight onto a bass drum.

![[May 24, 1965] Two faded stars (May Galactoscope #2)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/650524cover-672x372.jpg)

![[May 6, 1965] Back To Our Roots (<i>New Writings in SF4</i> & <i>Over Sea, Under Stone</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/New-Writings-and-Over-Sea-Under-Stone.jpg)

![[April 14, 1965] Furious Time Travel (April Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/650414coversnew-672x372.jpg)

![[February 26, 1965] Dare to be Mediocre (February Galactoscope #2)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/650226covers-655x372.jpg)

![[February 4, 1965] Space Prison of Opera (February Galactoscope #1)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/650206covers-672x372.jpg)

![[January 4, 1965] Madness: 2, Sanity: 1 (January Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/650104covers-672x372.jpg)