by Victoria Silverwolf

Galactic Journeyers from the United Kingdom have often spoken about the strange phenomenon known as Beatlemania. Not too long ago, CBS News offered a report on the craze.

This peculiar form of passionate devotion to four shaggy-haired musicians has made little impact here in the United States. That may change soon.

released January 10

released January 20

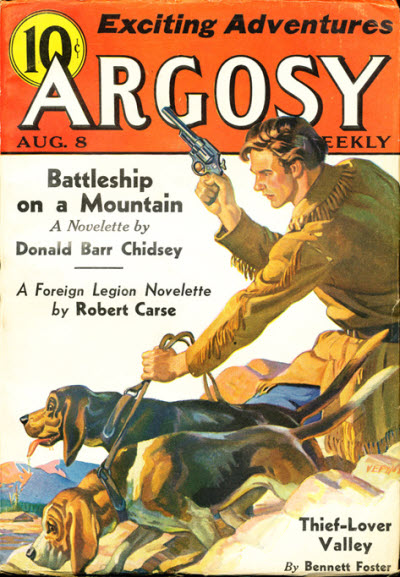

With the nearly simultaneous release of Beatles albums by two rival record companies this month, Yanks have the opportunity to judge the British quartet for themselves.

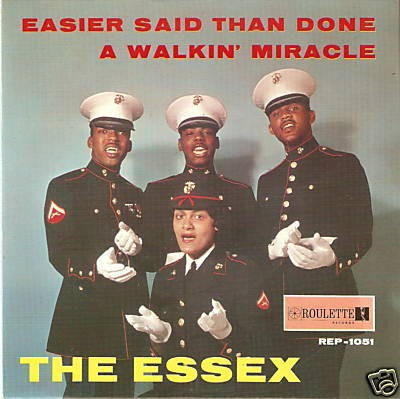

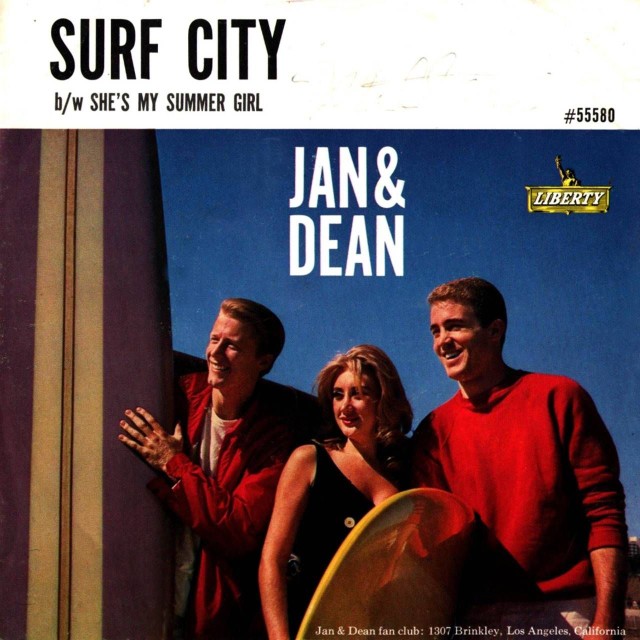

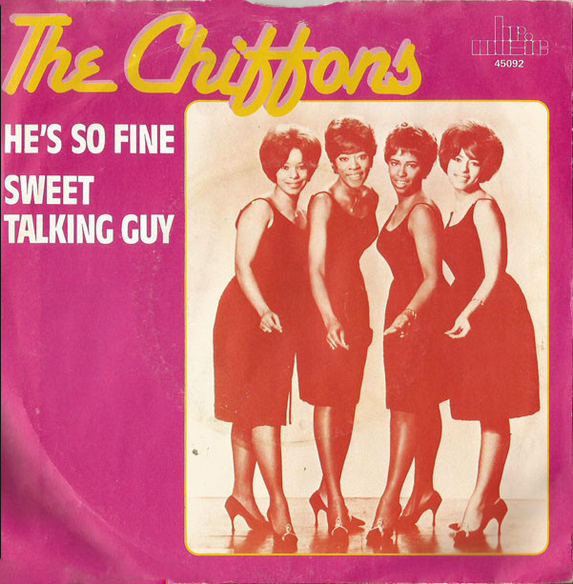

For now, Americans seem to prefer ballads to upbeat rock 'n' roll.

Originally a hit for baritone Vaughn Monroe nearly twenty years ago, crooner Bobby Vinton reached the top of the charts for the third time with his sentimental remake.

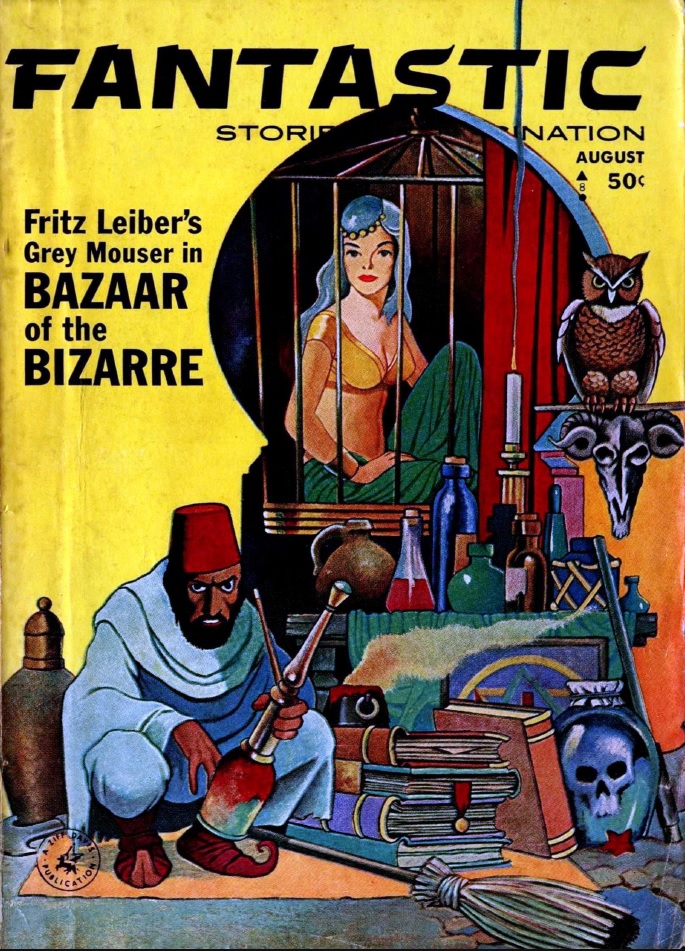

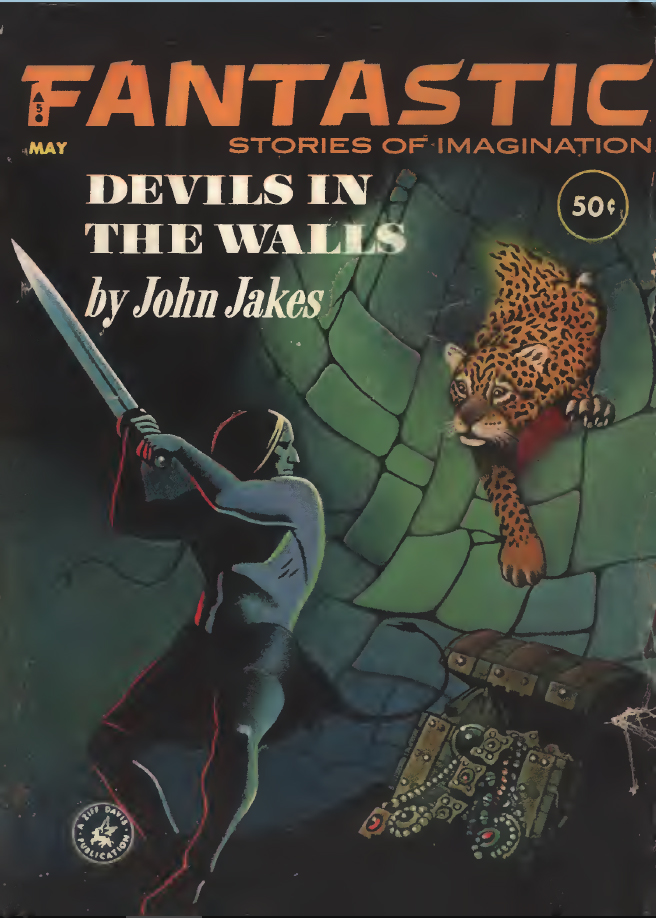

Whether or not the USA welcomes the foursome from Britain remains to be seen. It might be an omen that the latest issue of Fantastic features only American authors.

Novelty Act, by Philip K. Dick

This prolific author specializes in quirky accounts of tomorrow's fads and follies. His latest offering is no exception.

Most Americans live in gigantic communal apartment buildings. The government still allows voting, but there's only one political party. The President has no real power. The most revered figure is the First Lady, who is still young and beautiful after a century.

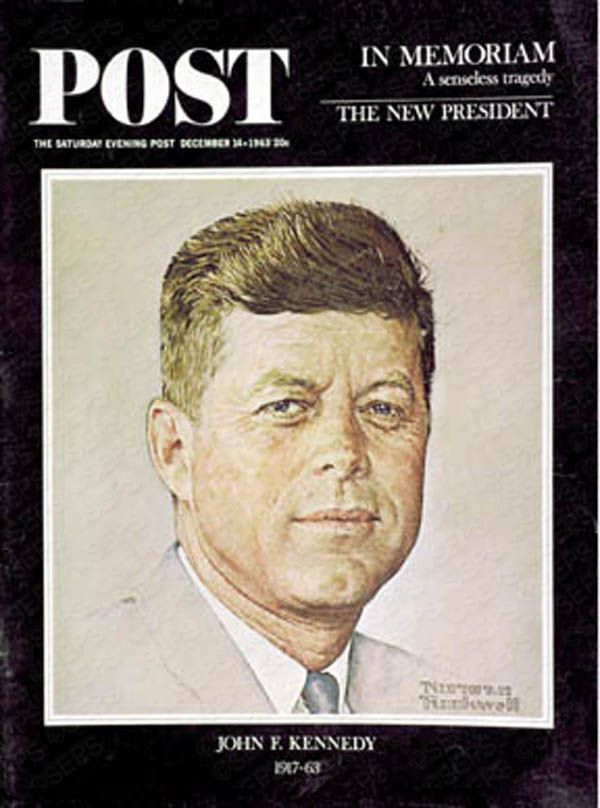

(The description of the character, and the way in which the nation idolizes her, suggest that she is a parody of Jacqueline Kennedy. The writer could not predict that the target of his gentle mocking would soon suffer a devastating tragedy.)

The protagonist dreams of winning the First Lady's favor by performing classical music with his brother on water jugs. The brother works at a spaceship dealer, with the help of a robotic imitation of an extinct Martian creature. The device, like the defunct Martians, can influence human minds. Everything comes together when the brothers make their appearance before the First Lady, and discover her secret.

This is a mixture of comedy and serious political satire. Imaginative details create a portrait of a neurotic future United States. A hint at the end that the brothers may escape their subtle dystopia lighten the story's mood. Although the plot is disjointed at times, it makes satisfying reading.

Four stars.

The Soft Woman, by Theodore L. Thomas

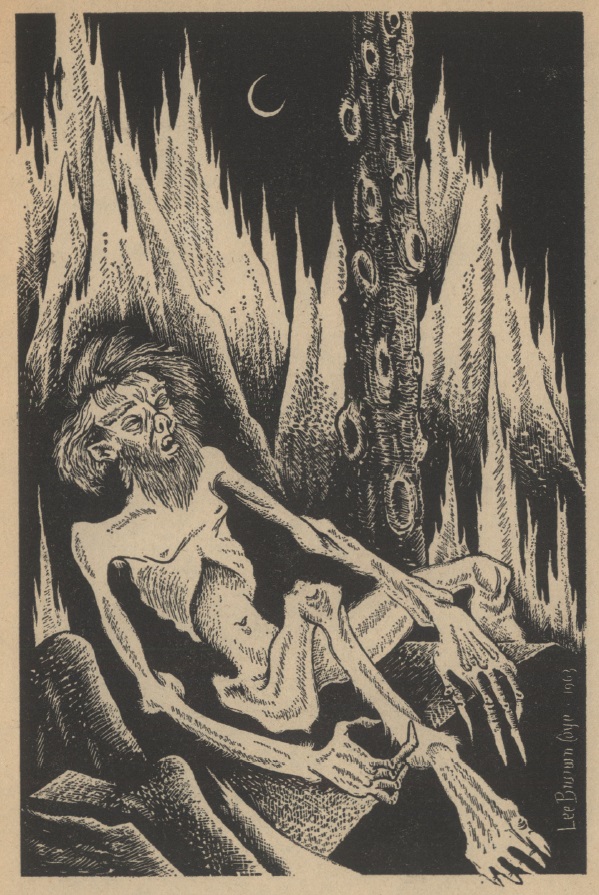

A man has a doll that looks like a naked woman with the head of a frog. He meets a beautiful woman and brings her to his room. A strange and frightening thing happens to him.

I can't say much more about this very brief story without giving away the ending. It confused me. I don't understand why the doll has a frog's head, or why it's named maMal [sic]. There seems no good reason for the man's unfortunate fate. There's some beautiful writing, but what does it all mean?

Two stars.

The Orginorg Way, by Jack Sharkey

An unattractive fellow who grew up alone in a Brazilian jungle has a strange ability to crossbreed plants into organic versions of technological devices. At first, he makes simple things like fishing rods. Eventually he creates substitutes for telephones and lightbulbs. He earns a vast fortune, enabling him to win the girl of his dreams. Of course, there's an ironic ending.

The absurd misadventures of the protagonist provide mild amusement. They way in which the plants imitate machines shows some imagination. As a whole, however, the story is too silly.

Two stars.

The Lords of Quarmall (Part Two of Two), by Fritz Leiber and Harry Fischer

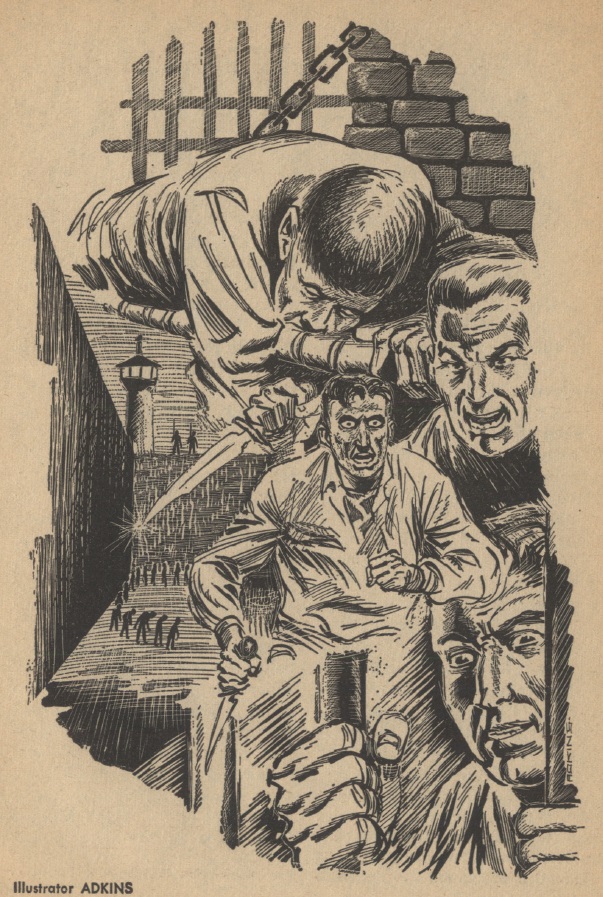

The conclusion of this short novel brings Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser together, along with the two rival brothers they serve, at the funeral pyre of the siblings' father. The death of the ruler of the underground kingdom leads to open warfare between his heirs. Sorcery and swordplay follow.

Disguise, deception, and skulking around keep the story moving at a rapid pace. A major twist in the plot near the end is predictable. Although there's plenty of colorful adventure, much of the hugger-mugger seems arbitrary.

Three stars.

They Never Come Back From Whoosh!, by David R. Bunch

In this surreal tale, people go inside a gigantic, soot-spewing building. They do not return. The narrator, like the others, feels a compulsion to enter the place, against his own will. Within he meets one of the building's strange caretakers.

This is a bizarre allegory of life, death, nature, and technology. The author's unique style is compelling, if not always lucid.

Three stars.

Return to Brobdingnag, by Adam Bradford, M.D.

A couple of months ago, the fictional Doctor Bradford journeyed to Lilliput, Jonathan Swift's land of tiny people. Now he visits the realm of giants. He finds out that they keep their population under control through death control instead of birth control. Whenever a baby is born, an elderly person takes poison to ensure a quick and painless demise. Their government is democratic, but the elite have more votes per person than the lower classes. The author also describes the science-based sun worship of the inhabitants, as well as their unusual way of performing surgery.

As with the previous installment in this series, the story takes far too long to get the narrator to his destination. The peculiar ways of the Brobdingnagians seem arbitrary, with no satiric point.

One star.

Death Before Dishonor, by Dobbin Thorpe

As we saw last month, Dobbin Thorpe is really Thomas M. Disch in disguise. Like Thorpe's creation in the previous issue, this is a tale of horror.

A woman wakes up from an alcoholic blackout and finds a tattoo on her thigh. She has no memory of how she got it. It turns out she had a one-night affair with a tattoo artist while she was drunk. The tattooist is a man of uncommon skill. His creations have a life of their own. The woman's romance with another man leads to terrifying consequences.

The story is gruesome, with a touch of very dark humor. Some might see it as a cautionary tale about drunkenness and promiscuity. I think the author just came up with a scary idea, and the plot grew out of it. On that level, it works well enough.

Three stars.

Summing Up

With eight Americans offering seven works of imagination, there are certain to be some stories you like and some you don't. I appreciate the wide range of fiction found here. We have satire, pastiche, adventure, allegory, comedy, surrealism, and horror. The only thing I'd like to stir into the mixture would be a few pieces from talented British writers. A story by Aldiss, Ballard, or Clarke – to mention just the ABC's of the UK – would be refreshing. Maybe the Beatles will add the same thing to American popular music. At least it would mix things up a bit.

(Did you read about all the ways the Journey expanded last year? Catch up and see what you missed!)

![[January 22, 1964] The British Are Coming! The Americans Are Here! (February 1964 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640122cover-513x372.jpg)

![[December 23, 1963] Ring Out the Old, Ring In the New (January 1964 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/631223cover-487x372.jpg)

![[November 9, 1963] Change and Constancy (December 1963 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/blog631109cover-400x372.jpg)

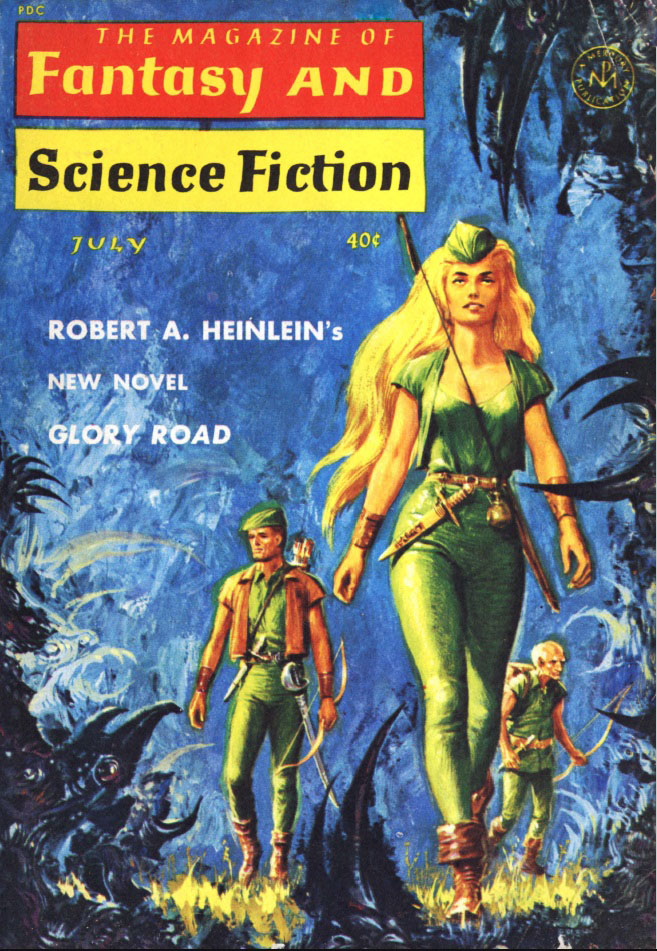

![[August 21, 1963] Forgettable (September 1963 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/630818cover-672x372.jpg)