by Mark Yon

Scenes from England

Hello again!

As I mentioned last month, I now am in the fortunate position of getting two British magazines a month. Both New Worlds and Science Fantasy have returned to monthly issues after being published in alternate months throughout most of 1964.

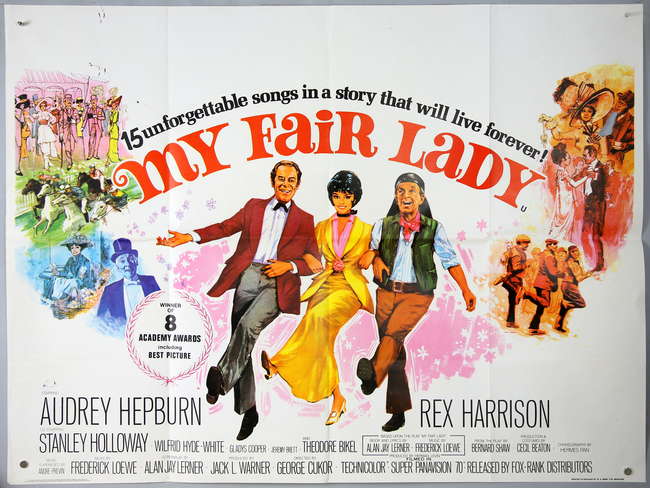

This doesn’t leave much time for other things this month. However, I can’t resist one update. Since our last article I have had to bite the bullet due to familial pressure and have been dragged along to the cinema to see the 170 minute epic that is My Fair Lady. Given my reluctance about musicals, I must admit, albeit quietly, that it wasn’t bad. Whilst I could make derogatory comments about Rex Harrison’s ‘singing’, Audrey Hepburn was quite charming. It’ll never make me want to see more musicals by choice, but it was tolerable.

And I must admit that it did relieve the sense of gloom that seems to have descended on the country following the sad news of Sir Winston Churchill's death. Moving on..

The First Issue At Hand

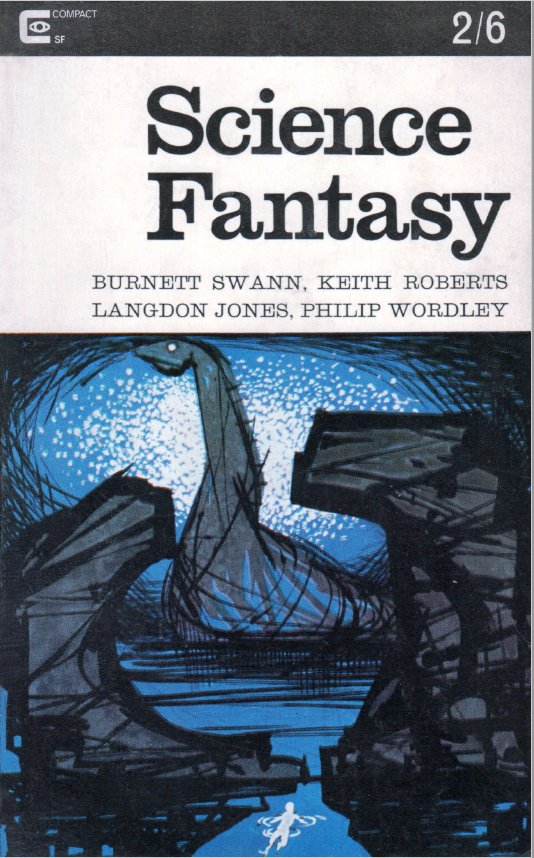

So: which magazine arrived first? The winner was the January/February 1965 issue of Science Fantasy.

The Editor is particularly pleased to point out that Keith Roberts, who seems to be our current favourite, will return with another Anita story next month (although the back cover tells us that it will be this month!)

Back Cover. Notice anything wrong?

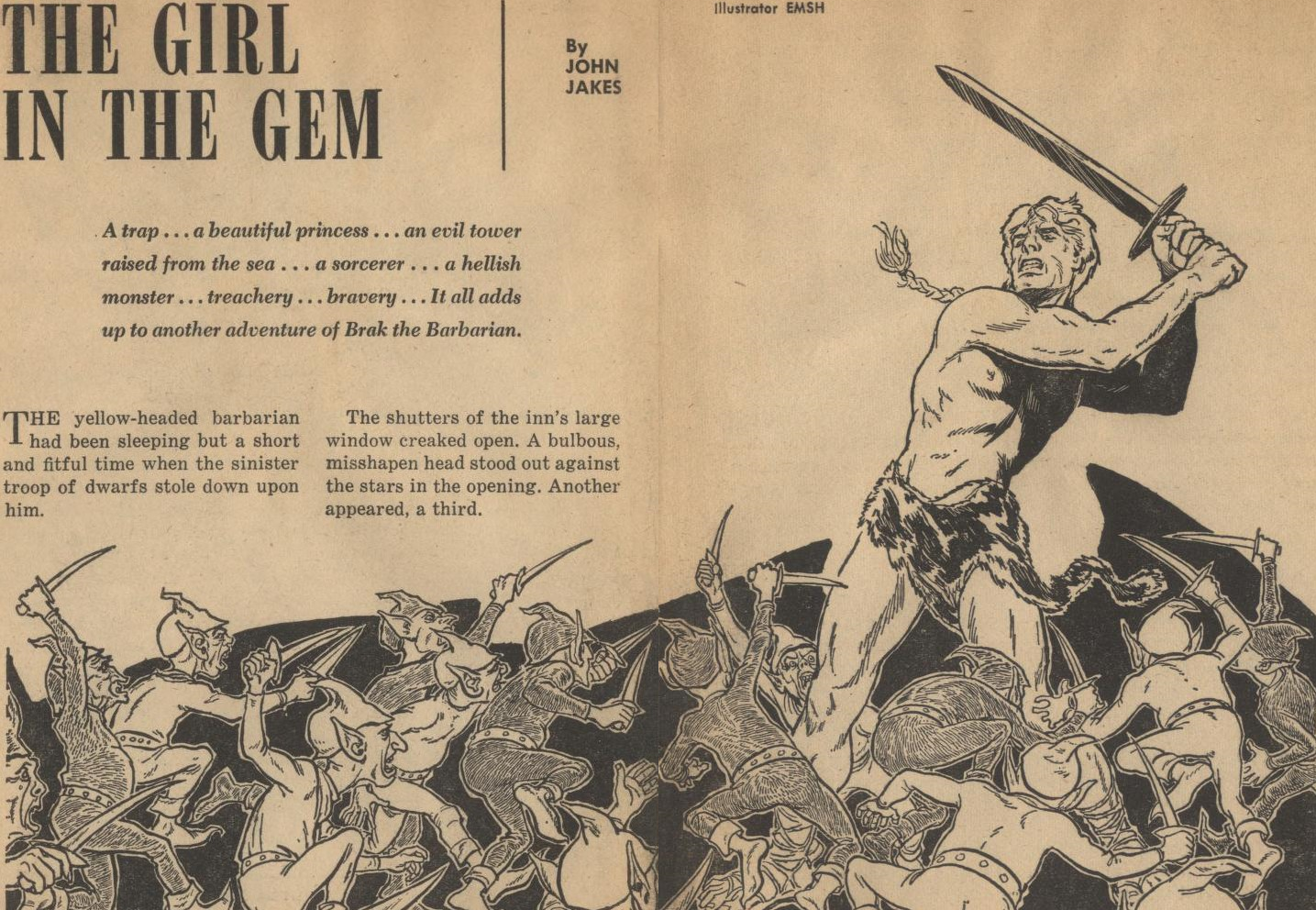

Multi-talented Mr. Roberts is also who we blame for this month’s rather obtuse cover art for the story Present From the Past.

To the stories themselves.

Present From the Past, by Douglas Davis

This is, to quote the editor from the Editorial, “a new twist on the time safari”. Doctor Messenger, palaeontologist, is transported by the Chronotransporter Research Department in a one-man machine to the Triassic to do research. Unsurprisingly, having been warned to be careful, things go wrong. This is a good old-fashioned adventure tale of Man against the dinosaurs. The descriptions of the landscape and the dinosaurs are vivid and suggest that this would make the start of a good movie, although despite the editor’s protestations, really is nothing that different from the sort of pulp story published in the 1930’s. It ends weakly and feels like there should be more, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing but therefore doesn’t feel like a story with a point. 3 out of 5.

The Empathy Machine, by Langdon Jones

Not content with being the Assistant Editor over at New Worlds, here we have the latest story from Langdon Jones, the writer. As we might expect, it is odd story, one that seems to be an internalised fever dream by Henry Ronson, a man who has the urge to kill his frigid wife whilst on holiday on Mars. The story takes an odd turn when Ronson damages the wall screen in frustration at the incessant advertising that he is bombarded by and is then beaten up by the police who arrive to investigate. The next day Ronson and his wife discover a strange Martian building, which on entrance shows Henry life from the perspective of his wife. And guess what – she wants to kill him as well! Now having empathy for each other they kiss and make up (I presume).

Really though, this is a salutary tale on the need for partners to communicate with each other – as well as point out the maddening impact of constant advertising! It just reads strangely to me, an uneven attempt to combine the mysticism of Ray Bradbury with the angst of J G Ballard, which doesn’t work, although the effort is appreciated. 3 out of 5.

Harvest, by Johnny Byrne

And here’s the return of the writer of appropriately weird stories, Johnny Byrne, last seen in the September – October 1964 issue. Harvest has a similarly odd, disjointed tone to the Langdon Jones story, telling of characters who seem to be living in a post-apocalyptic place. It is odder than Langdon Jones’s story, and whilst I liked the lyrical nature of the prose, not really for me. 2 out of 5.

Petros, by Philip Wordley

A new writer to me. The title evokes a sense that it is something akin to Burnett-Swann’s re-imagining of Grecian myths, but instead it is another story that shows us that post-Armageddon life is bad. This time the Plenipotentiary of the Kingdom of Christ on Earth appears to be living in (another) post-apocalyptic world surrounded by what appear to be Mafia gangsters transported to Britain. This was easier to understand than Johnny Byrne’s story, but as yet another tale about the enduring importance of religion in difficult circumstances (a common theme in the magazines in the last few months!) it left me strangely unmoved. 3 out of 5.

Flight of Fancy, by Keith Roberts

Another story from Science Fantasy’s current flavour of the month – he appears later in the issue as well. It helps that I generally like Keith’s writing, although this very short story is underwhelming. Flight of Fancy is a minor tale that tries to use humour to tell us how science could become unimportant in a future where science has allowed civilisation to be bombed back to a more primitive level. 3 out of 5.

Only the Best, by Patricia Hocknell

A new writer. This is a short story that is a variant of the adage “Don’t look a gift horse in the mouth.” A marvellous new invention that appears from who-knows-where has negative consequences. Even if I accepted the point that “Washing clothes can be fun”, there were issues with the story for me. I think that it’s meant to be funny but comes across as both silly and creepy. It’s OK, but is a one-point tale. 2 out of 5.

The Island, by Roger Jones

Another new writer. A fairly unpleasant tale of how three characters named Erg, Rastrick and Minus spend their time surviving on some island of the future. It’s all rather grim and depressing, not helped by some rather dreadful people. There’s a weak attempt to develop a sense of mystery – what did Erg see Rastrick doing in the copse on the island? – but the solution is pretty unremarkable. With such misery, the ending is a bit of a relief, but I did wonder what was the point at the end. A story intended to score on its shock value, I believe, but just comes across as unremittingly bleak. 2 out of 5.

The Typewriter, by Alistair Bevan

Here’s the second story in this issue by Keith Roberts this issue, albeit written under the name of one of his pseudonyms. After all that unrelenting misery of The Island, here’s a lighter tale, telling us of what happens to Henry Albert Tailor, the creator of ‘Flush Hardman’, an action hero whose similarity to the overheated exploits of James Bond is surely just a coincidence. There’s a touch of The Twilight Zone here when the author’s typewriter seems to have a mind of its own and is perhaps more the creator of the popular stories than Henry realises. It’s silly but quite fun and not nearly as jarring as some of the other stories in this issue have been. 4 out of 5.

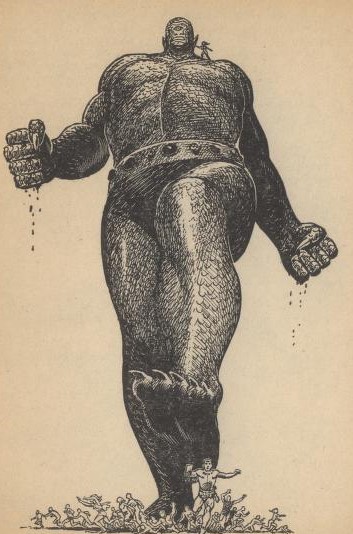

The Blue Monkeys (part 3), by Thomas Burnett Swann

The last part of this serial is as good as its previous parts. Here we discover what happens when Ajax attacks Eunostos the Minotaur’s home in an attempt to retrieve our two wayward teenagers Thea and Icarus, although really, it’s about Ajax trying to get Thea, having being spurned before, and, to quote the story, “ravish her”. Much of the first part of this month's serial deals dramatically with the battle between Ajax and the beasts of the forest, which is very well done. The last part of the tale is surprisingly elegiac with an unexpectedly delightful bitter-sweet ending.

I am surprised how much I have enjoyed this story. I might even go as far as to say that for me this is one of the best serials I have read in years. 4 out of 5.

Summing up Science Fantasy

Bit of a mixture this issue. It’s not bad, but at the same time not the best issue I’ve read. Nothing really stands out other than the Burnett Swann serial. Overall it feels a bit depressing and downbeat. More worryingly, we seem to be repeating the same ideas over and over, things that are variations on what we’ve read before. I’m getting a bit fed up of bleak post-apocalyptic tales for one. In summary though, this is an eclectic mixture of the good and the downright odd, and I suspect that the range will elicit a range of responses.

The Second Issue At Hand

And so, hoping for a more positive experience, I turned to the February 1965 New Worlds. Last month’s issue was a cracker, so I was keen to read this one.

Cover by Jakubowicz

Whereas I’ve noticed both of the Editors stamp their personalities in the two magazines lately, New Worlds’s editorial this month is more of a news summary than an actual Editorial.

Both Moorcock and Bonfiglioli have used the space in the past to put forward a particular view, like say John W. Campbell in Analog, but instead the New Worlds Editorial this month appears to be a perfunctory one about what is going on in the genre scene around Britain. There's some things that are good to know, but with the resultant loss of identity, I suspect that this is less Moorcock’s handiwork and perhaps more by Assistant Editor Langdon Jones.

The most exciting thing mentioned this month is that Britain will host a World Convention for only the second time, in August in Mayfair, London. The Guest of Honour will be Brian W. Aldiss, which all sounds very thrilling.

The Power of Y (part 2), by Arthur Sellings

The second and final part of this story turns all James Bond-ian, with Max Afford’s revelation last month of a big conspiracy – that (warning: plot revelation ahead!) the President of the Federated States of Europe is a Plied copy, and only he can tell! No reason for this new skill is ever given, incidentally, but it’s not really relevant to the bigger picture. The last part of this story continues the idea that someone is covering up what happened, and this includes getting rid of the inventors of the Plying method and Max rescuing the copied President. It is an excitingly written, fast-paced tale that had a great twist in the end that managed to actually tie things up – I wish I could say that for every story I read in these magazines!

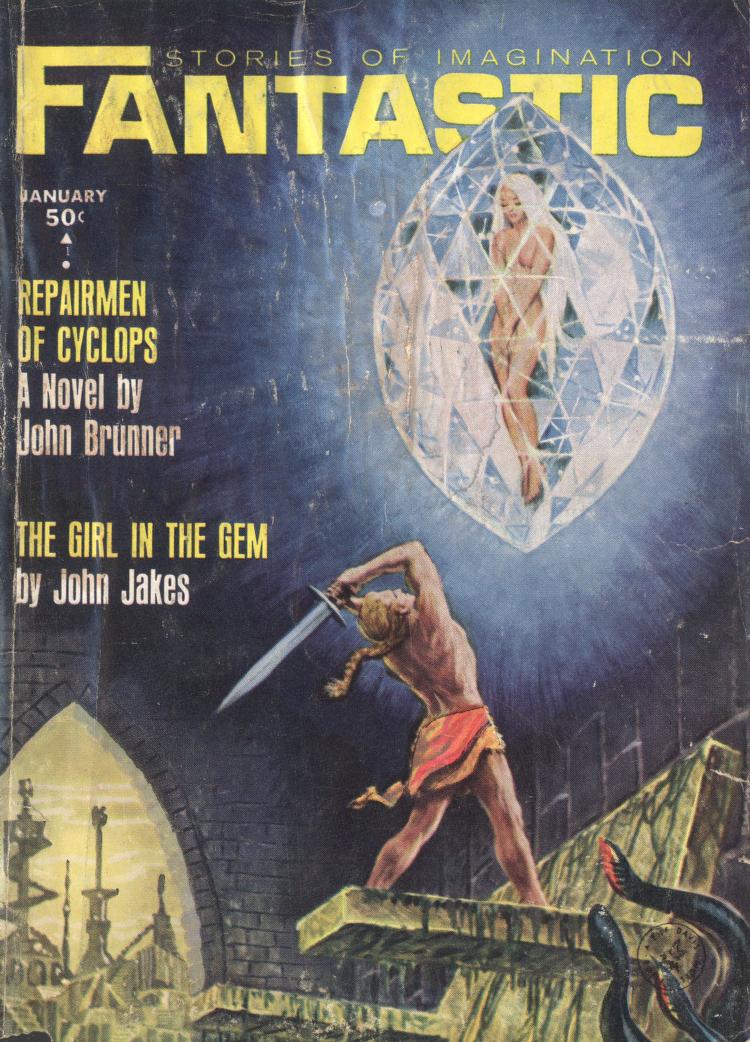

Oh look- more rubbish artwork!

Despite the artwork, I am very pleased with this one overall, one of the few serials in New Worlds I’ve really liked over the past year or so. 4 out of 5.

More Than A Man, by John Baxter

Although this follows a similar theme to Sellings’ story of secret identity, this is a rather old-fashioned story. It’s an adventure tale, combining Galactic Empires (not the first time we’ll hear of those this month!) and spymanship, as Graves and Bailey travel the Galaxy servicing robots that have been placed in key positions of power in an ongoing covert war. Think of it as a Space Opera version of Rudyard Kipling’s Empirical adventure Kim mixed up with Asimov’s Robotics stories. Australian John Baxter (last seen in Science Fantasy last April) tells us an exciting yet perfunctory tale. It’s fun and I enjoyed it a lot, but it is nothing that would be out of place from the magazines of the 1950’s. 3 out of 5.

When the Sky Falls, by John Hamilton

The second of our stories involving someone named John this month is another story examining religion, a topic I’m heartily sick of, to be honest. But I can’t deny that it’s a weighty topic, even when this story is brief, and one that many seem happy to examine through the auspices of a science fiction magazine. As the title suggests, this is a tale of Armageddon and what happens when the day of judgement arrives. For such a momentous event there’s nothing particularly notable about it. 2 out of 5.

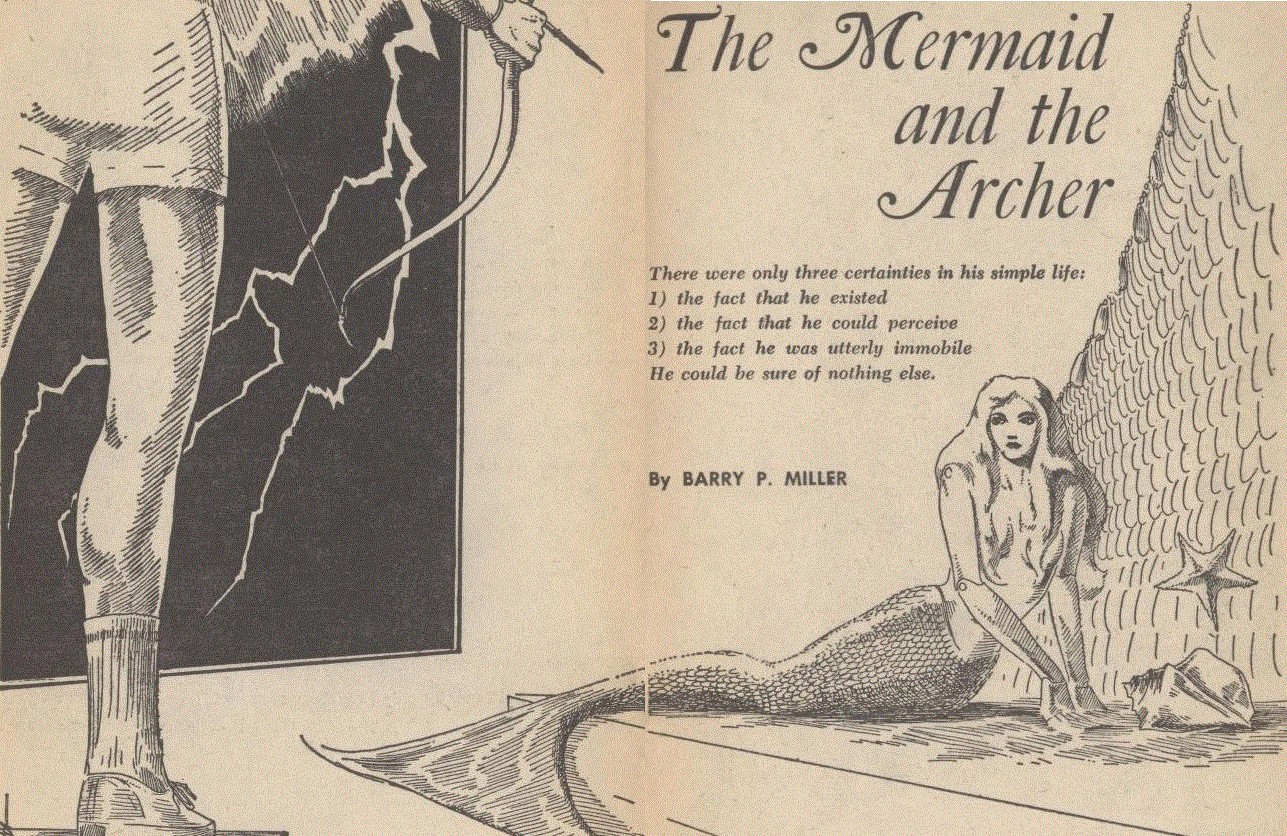

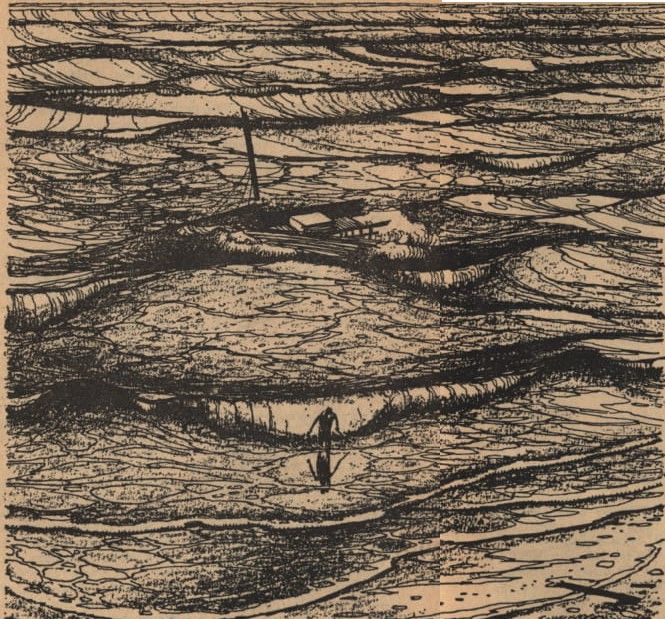

This is better! Artwork by James Cawthorn

The Singular Quest of Martin Borg, by George Collyn

This lengthy tale treads a similar path to Mr. Collyn’s last story, Mixup, in the November-December 1964 issue, as it is a parody. It is undoubtedly hyper-enthusiastic, telling of how Martin Borg came to be. It is a story with everything thrown in, deliberately using the purpliest of pulp prose to flit across science-fictional ideas of Cosmic Minds, matter transference and Galactic Empires, as we are told of Martin’s odd parentage and ensuing education and growth.

As a result, it varies wildly from parts that hit their target well to other sections that are just over-excitedly silly. It is rather amusing to have this parody of Asimov’s robotics and Galactic Empire stories alongside John Baxter’s more straightforward version earlier in the magazine. Which, in itself, is a point, I guess. I liked some of it, but at the same time I’m a tad uncomfortable with a story that makes a joke out of rape. 3 out of 5.

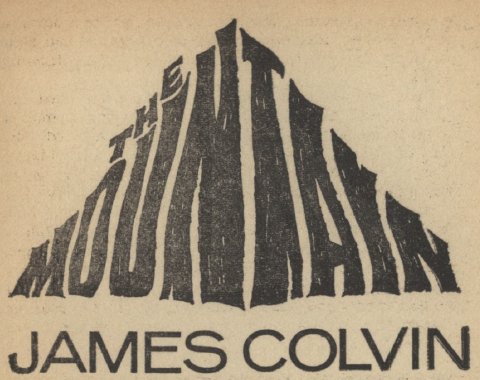

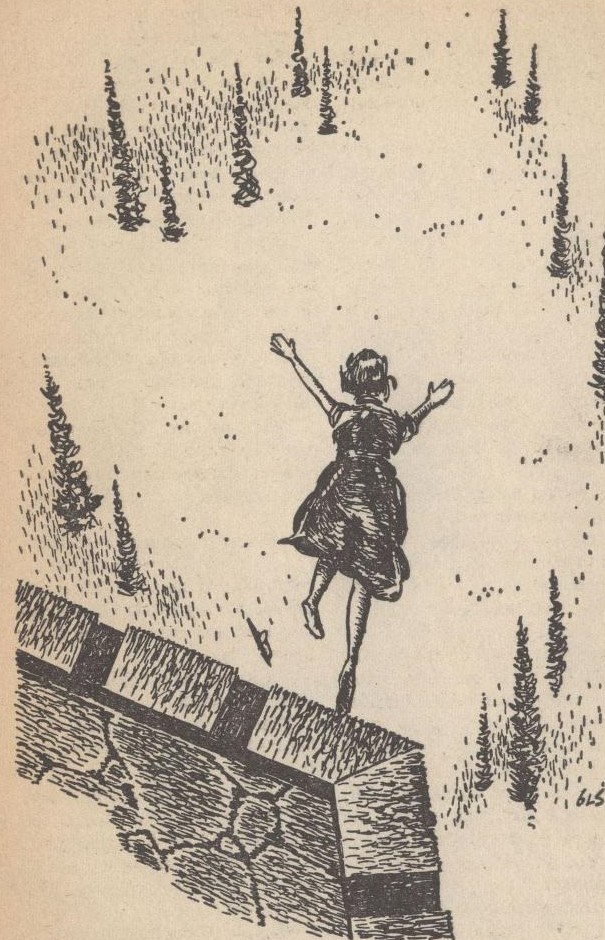

The Mountain, by James Colvin

Moorcock’s latest under his nom de plume is a story of two men in (another) post-apocalyptic environment who are in Swedish Lappland on the trail of a young woman. As the story progresses the purpose of the plot changes from trying to meet the young girl to surviving climbing a mountain. It’s really all about the need for human challenge. There’s some nice musing on time and place and Man’s insignificance in all of this, but it is a story with limited potential and the now inevitable dour conclusion. 3 out of 5.

Box, by Richard Wilson

A strange tale of Harry McCann, whose existence is in the latest space saving economy, a 7 x 7 x 5 feet box. Eating, sleeping and basically living his life as an artist & illustrator is all contained in this restricted space. It sounds unlikely but this story of a future with no physical human contact gets its message across without becoming tedious. 3 out of 5.

Articles

I suspect partly inspired by the new critical magazine SF Horizons, mentioned last month, Moorcock seems to be reintroducing more reviews and literary criticism than we’ve seen for a while. There’s an increased amount of articles this month, scattered through the magazine.

Biological Electricity attempts to do what the Good Doctor Asimov does so much better in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction. This short article looks at how electricity generated spontaneously by living creatures could be used in the future. It’s informative but not as accessible as your American equivalent.

Can Spacemen Live With Their Illusions? is an article that shows us how space exploration may be hampered by the psychological as well as the physical effects on the intrepid travellers dealing with a new environment.

Book Reviews

In terms of Books this month, Mike Moorcock as James Colvin reviews The Worlds of Science Fiction by Robert P. Mills, and Introducing SF by the already mentioned soon-to-be-Worldcon-Guest-of-Honour Brian W. Aldiss. Brief mention is also made of Harry Harrison's The Ethical Engineer, The Paper Dolls by L. P. Davies, Galouye's The Last Leap and John Lymington's The Sleep Eaters as well as the reissue of some classic horror novels.

We also have a number of more in-depth reviews. James Colvin (remember him?) writes another celebratory review of Burroughs – that’s William S., not Edgar Rice – this time for his novel The Naked Lunch. At 42 shillings, though – nearly three times the price of an average hardback book – you've got to have some serious money to take the plunge.

Newcomer Alan Forrest pens an enthusiastic essay entitled Did Elric Die in Vain? about Mike Moorcock’s Fantasy character Elric (who was once a staple of Science Fantasy, now seemingly transferred over to New Worlds) in the novel Stormbringer and Hilary Bailey (aka Mrs Mike Moorcock) reviews Who? by Algis Budrys, summarised nicely by its title, Hardly SF.

No ratings this month but there is news that the next issue will include a JG Ballard story. Hurrah!

Summing up New Worlds

New Worlds is an eclectic mixture this month and there are signs that Moorcock is making his own stamp on the magazine. The addition of factual science articles and more literary reviews reflect this, and it must be said that the expansion of literary criticism has been one of Mike’s intentions since he took over as Editor. It’ll be interesting to see how the regular readers respond to it.

By including such material of course means that there’s less space for fiction, and I suspect that whilst that might ease Moorcock’s load a little – he is writing and editing a fair bit of it, after all – it may not sit well with readers. But then we are now monthly…

Summing up overall

Both issues read this month are pretty strong. I enjoyed the eclecticism of New Worlds, whilst Science Fantasy had some of the best stories amongst the less endearing. Consequently, both score well, but for different reasons. However, in this battle of the magazines I declare New Worlds the winner for me this month.

And that’s it for this time. Until the next…

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

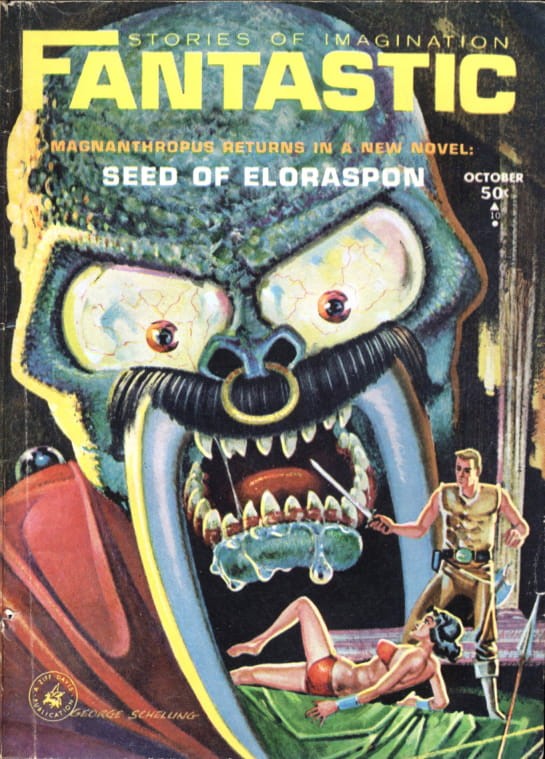

![[January 24, 1965] A New Beginning… <i>New Worlds and Science Fantasy Magazine, January/February 1965</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Science-Fantasy-Jan-65-534x372.png)

![[January 22, 1965] With Apologies to Rodgers and Hammerstein (February 1965 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/FANTFEB1965-2-458x372.jpg)

![[December 23, 1964] Odds and Ends (January 1965 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Fantastic_v14n01_1965-01_0000-2-672x372.jpg)

![[November 21, 1964] Bridging the Gap (December 1964 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Fantastic_v13n12_1964-12_0000-2-672x304.jpg)

![[October 24, 1964] Nothing Lasts Forever (November 1964 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Fantastic_v13n11_1964-11_0000-4-672x205.jpg)

![[September 24, 1964] Looking Backward (October 1964 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/fantastic_196410-3-383x372.jpg)

![[August 25, 1964] Combat Zones (September 1964 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/FANTSEP1964-e1565757244659-427x372.jpg)

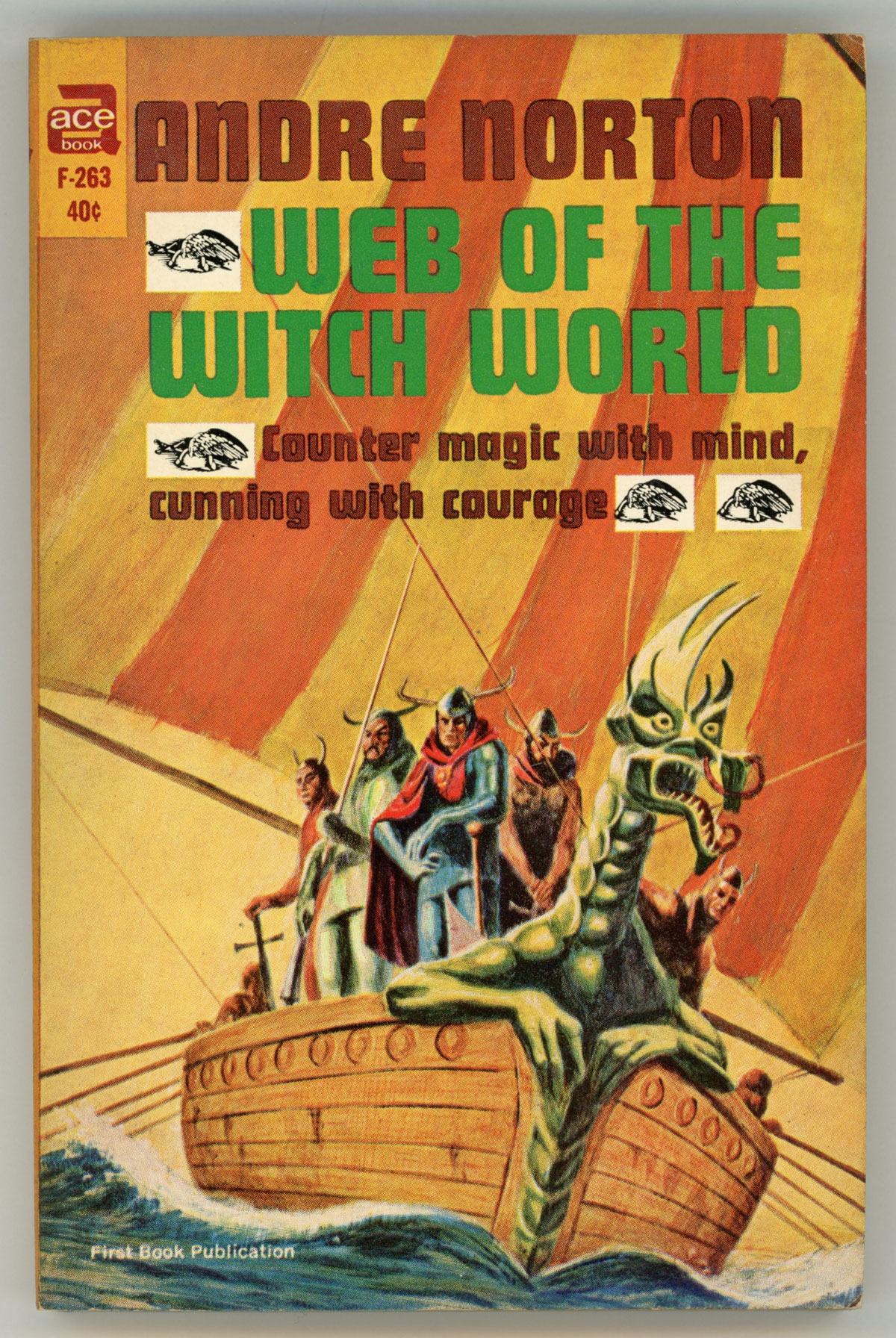

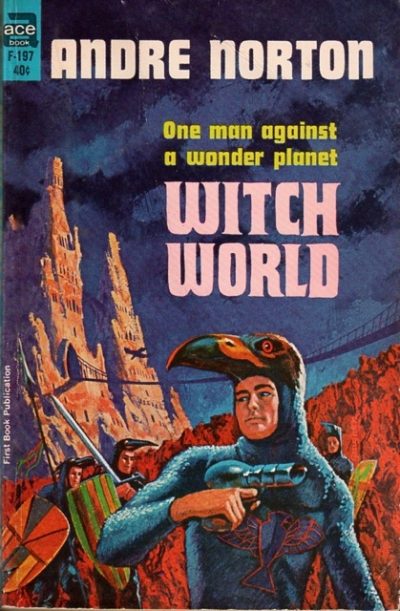

![[April 16, 1964] Of Houses and World Building (Jack Vance's The Houses of Iszm/ Son of the Tree and Andre Norton's Web of the Witch World)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/640416double-640x372.jpg)

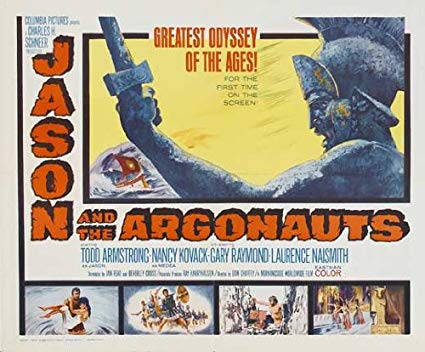

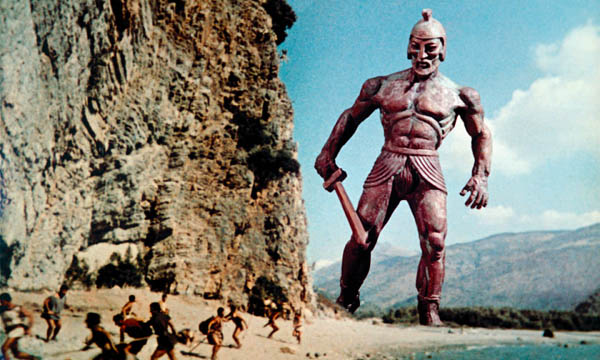

![[December 25, 1963] Animating an Epic (Don Chaffey's <i>Jason and the Argonauts</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/631225argonautsposter.jpg)

![[Oct. 30, 1963] <i>Jim Knopf and Lukas the Train Engine Driver</i> by Michael Ende: A Classic in the Making](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/631030Cover_Jim_Knopf_English.jpg)